Psychology 2012. Vol.3, No.4, 304-309 Published Online April 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/psych) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/psych.2012.34043 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 304 Quality of Life, Self-Efficacy and Psychological Well-Being in Brazilian Adults with Cancer: A Longitudinal Study Elisa Kern de Castro1, Clarissa Ponciano1, Bruna Meneghetti1, Marina Kreling1, Carolina Chem2 1Sinos Valley University, São Leopoldo, Brazil 2Santa Rita Hospital, Porto Alegre, Brazil Email: elisa.kerndecastro@gmail.com Received October 25th, 2011; revised January 17th, 2012; accepted March 2nd, 2012 Quality of life (QoL) has been considered worthy of assessment in the treatment, prevention and rehabili- tation of cancer patients. As it has a psychological dimension, is important to investigate the relationship between quality of life and psychological concepts like self-efficacy and psychological well-being. Ob- jective of the present study is to examine the QoL, self-efficacy and psychological well-being in adults with cancer. Methods: 50 patients completed self-report questionnaires: WHOQOL-bref, General Self- Efficacy Scale and GHQ-12 in two periods (T1 = timeline; T2 = follow up 1 year later). A paired t-test did not identify significant differences in the QoL self-efficacy and psychological well-being between T1 and T2. However, men had a better overall QoL and in the physical and social dimensions, and psycho- logical well-being in T1 compared with the women. In T2 there were significant differences between men and women only in the social and psychological dimensions of the QoL. The self-efficacy in T2 was the only predictive variable of the QoL in T2, explaining 71.9% of its variance. It is concluded that, in the pe- riod of one year, the QoL, psychological well-being and self-efficacy were stable, but gender differences were identified. The variables measured in T1 were incapable of predicting the QoL in T2. The gender differences found in QoL and psychological well-being can be used to guide specific future interventions with these patients. Keywords: Cancer; Oncology; Quality of Life; Self-Efficacy; Well-Being; Longitudinal Study Introduction With advances in health areas the life expectancy of patients with cancer has been prolonged, leading to concern regarding the assistance for and quality of life (QoL) of these patients (Seidl & Zannon, 2004). Thus, the concept of QoL has been used in the area of health and has been considered worthy of assess- ment in the treatment, prevention and rehabilitation of sick patients. The QoL is related to the health concept proposed by the World Health Organization (WHO)—physical, mental and so- cial well-being. It means the individual’s perception of his/her own health generally speaking, according to his/her cultural demands, value systems, goals, expectations and concerns. This explains why individuals with similar objective indicators of QoL can have quite different indices in the subjective QoL (Seidl & Zannon, 2004; Mayo, Moriello, Asano, Van Der Spuy, & Finck, 2010). A recent systematic review of the Brazilian literature about the QoL and cancer (Bertan & Castro, 2009) showed the grow- ing number of empirical studies related to the issue, which, on the whole, related the QoL to the impact of the disease and of the treatment. Nevertheless, other issues were dealt with, as the QoL and diagnosis and validation of instruments. In another study Montazeri (2008), a bibliographic review was made about the QoL in patients with breast cancer, encompassing all the publications in English in biomedical publications, between 1974 and 2007. A large number of the articles dealt with the construction and validation of instruments of assessment of the QoL, surgical treatment, systemic therapy, the QoL as a pre- dictor of survival, psychological suffering, care support, symp- toms and sexual dysfunction disorders. As it has a psychological dimension, the QoL has been re- lated to different concepts of this nature, and one of them is self-efficacy. According to Bandura (1997; 2001), self-efficacy consists of beliefs and/or perceptions which individuals have about their own potential to develop any type of activity pro- vided that it generates the results desired. This belief in per- sonal competence provides the basis for motivation of the hu- man being, well-being, self-fulfillment and expectations of re- sults (Bandura, 2001). There is evidence of the importance of self-efficacy in pro- ducing better results in health (Bandura, 1997). More specifi- cally, concerning self-efficacy and the QoL of patients with cancer, research has shown a positive association between these two variables, including reduced stress of the patients (Kreitler, Peleg, & Ehrenfeld, 2006), improved relations with caretakers, and increased physical activities (Perkins, Baum, Taylor, & Basen-Engquist, 2009). As well as self-efficacy and the QoL, psychological well- being is also a concept which has been associated with good results in health. The meta-analytical study performed by How- ell, Kern and Lyubomirsky, (2007) which assessed the impact of more than 150 studies concerning well-being on health showed that, both short- and long-term, well-being is related to the capacity of controlling symptoms of diseases, especially regarding the impact on the immunity system and resistance to  E. K. DE CASTRO ET AL. pain. In patients with cancer, the concern has been to encourage their psychological well-being and improve their QoL (Kwan, Ergas, & Somkin, 2010; Ramachandra, Booth, Pieters, Vrotsou, & Huppert, 2009). Rottman, Dalton, Christensen, Frederiksen and Johansen (2010) found that, in women with breast cancer, self-efficacy was a predictor of emotional well-being one year afterwards, but was not related to physical and social well- being. Thus, the present study aimed to make a longitudinal as- sessment (one year—T1: first data collection; T2: one year after the first one) the quality of life, self-efficacy and psychological well-being of adults with cancer, also examining possible dif- ferences between men and women. Moreover, it sought to as- sess the predictive power of these same variables in T1 and of self-efficacy and well-being in T2 for the quality of life in T2. From the studies reviewed, the hypothesis was that the three constructs assessed would be strongly correlated in the two data collection stages and that, one year after the first assessment, the patients would have higher indices of the quality of life and psychological well-being due to being more adapted to the treatment. It was also expected that the quality of life of all the variables measured in T1 would predict the quality of life in T2. Material and Methods Participants 50 youthful patients with different types of cancer, with an average age of 33.3 years old (SD = 5.5) took part in the study both in T1 and T21. All the participants were outpatients in the Unique Health System (SUS) at a reference hospital in the treatment of cancer in a town in the south of Brazil. The pa- tients were selected in a consecutive manner among those waiting for medical appointments at the outpatients unit of the hospital in T1. For the present study, the sample only refers to patients who responded to all the instruments in the two data collections (T1 and T2). The main types of cancer diagnosed in the patients of the sample were as follows: breast (16), rectum (4), uterus (4), melanoma (3), sarcoma (3), and mouth (3), among other less frequent types totaling 17 patients. The aver- age of time since diagnosis was 2.8 years old. Fifteen (30%) of the patients in T2 were in treatment to control metastasis, whereas 35 patients (70%) were in maintenance treatment. In Table 1 there is other biosociodemographic data of those par- ticipating in the study. Instruments World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment In- strument—short version (WHOQOL-bref) (Fleck et al., 2000): instrument developed by the WHO which aims to assess the QoL in different cultures. The WHOQOL-bref consists of two general questions and 24 questions which compose each one of the 24 facets making up the original instrument of 100 ques- tions. The four domains of the instrument are: physical, psy- chological, social relations and environment. For each question there are five degrees of intensity. The higher the individual’s score in the questionnaire, the better his/her QoL is. Concerning Table 1. Biosociodemographic and clinical data. T1/N (%) T2/N (%) Sex Male 17 (34%) - Female 33 (66%) - Schooling Elementary incomplete 21 (42%) - Elementary complete 6 (12%) - High school incomplete 6 (12%) - Secondary complete 11 (22%) - Higher education incomplete 6 (12%) - Work Works 24 (48%) 19 (38%) Does not work due to the disease 20 (40%) 31 (62%) Marital status Single/Separated 17 (34%) 18 (36%) Married/Lives together 33 (66%) 31 (62%) Widow(er) - 1 (2%) Metastasis No 38 (76%) 35 (70%) Yes 12 (24%) 15 (30%) Family history of cancer No 14 (28%) - Yes 32 (72%) - Type of treatment used Chemotherapy 30 (60%) 18 (36%) Radiotherapy 23 (46%) 8 (16%) Surgery 44 (88%) 17 (34%) Admission in the last year No - 35 (70%) Yes - 13 (30%) the internal consistency, Cronbach’s Alpha value in the present study was 0.71 (T1) and 0.86 (T2) for the total QoL. General Health Questionnaire—GHQ-12 (Goldberg, 1978; Gouveia et al., 2003): It is a series of 12 statements about the state of health of people in general, and aims to identify psychi- atric diseases which are not serious. The individual’s task con- sists of saying if the statements apply to him/her, or not. The GHQ-12 is a short version of the instrument, derived from the original scale which consists of 60 items. The higher the score on the instrument, the greater his/her symptoms of psychiatric diseases and, therefore, the less his/her well-being. In the pre- sent study, Cronbach’s Alpha was 0.85 (T1) and 0.89 (T2). General Perceived Self-Efficacy Scale (Schwarzer, Boehmer, Luszczynska, Mohamed, & Knoll, 2005): It consists of 10 items which assess the individual’s perception of self-efficacy, and the answers vary from 1 (it is not true) to 4 (it is always true). Higher scores indicate a greater perception of self-effi- cacy. The Brazilian Portuguese version was used in studies which did not aim to gather information about the psychometric properties of the scale, but the scale had a very high reliability (Teixeira, & Dias, 2005). Cronbach’s Alpha of the scale in the present study was 0.82 (T1) and 0.83 (T2). 1In T1 151 patients took part, but in T2 it was perceived in the hospital records that 16 patients had died, 15 patients refused to take part in the se- cond phase and 80 patients were not located (they were not undergoing hospital treatment, and the hospital records were not updated in order to allow contact to be made again). Design and Procedures The study is of a longitudinal nature. Both the first data col- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 305  E. K. DE CASTRO ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 306 lection (T1) and the second one, twelve months after the first one (T2), occurred in a hospital specialized in cancer. The re- searchers in T1 found in the hospital records those patients who were undergoing treatment for cancer. Having identified the patients, they were invited to take part in the study and were taken to a room in the outpatients unit of the hospital. The instruments were filled in by the interviewers, who read the questions aloud and marked the option matching the answer of those taking part. It was decided not to use the self-applica- tion form of the instruments as many patients had little school- ing and difficulty in reading and filling in the questionnaire. In T1, the questionnaires were applied before the routine medical appointments of the patients, in a reserved room. In T2, the instruments were applied in the same place, but the meeting was scheduled beforehand by telephone. Research Ethical Procedures This study was previously approved by the Ethics Committee of the Santa Rita Hospital. All the participants signed the In- formed Consent before the questionnaires were applied. Data analysis All the research protocol data was tabulated in the database of program SPSS 18.0. The confirmation of the parametric criteria of the sample and the internal consistency of each in- strument were analyzed. Then, the test of Pearson’s correlation was applied in order to assess the correlations between the QoL, self-efficacy and psychological well-being in T1 and T2. Af- terwards, a paired t-test was performed to assess possible dif- ferences between the measures of the QoL, self-efficacy and general health between T1 and T2, and so was the independent t-test in order to compare the level of the QoL, self-efficacy and general health as per the gender of the participants. Finally, linear regression analysis (stepwise method) was performed to assess the predictive power of the independent variables which had a significant correlation with the QoL in T1, well-being in T1 and T2 and self-efficacy in T2 for the QoL in T2. Results Initially, the analysis of the test of Pearson’s correlation showed that in T1 the total QoL and all its dimensions corre- lated positively in a moderate to strong manner with the self-efficacy in T1 and negatively with the well-being in T1, indicating that the greater the self-efficacy and psychological well-being, the greater the QoL (as per Table 2). Also in T1, the self-efficacy and psychological well-being also had signify- cant and moderately negative correlations, indicating that the greater self-efficacy was related to higher indices of well-being. The results of the total QoL and its dimensions in T1 and T2 were not significantly correlated. In T2, the self-efficacy corre- lated significantly with the total QoL and its physical dimen- sion, and the psychological well-being in T2 correlated signify- cantly and negatively with the total QoL in T2 and with the physical, social and environmental dimensions. Next, the paired t-test was performed in order to compare the averages of the total QoL and its dimensions, self-efficacy and psychological well-being longitudinally (T1 and T2). The re- sults did not show significant differences between the two phases, indicating a stability of the results in the interval of one year in these patients (Figure 1). The independent t-test, performed to assess possible differ- ences between men and women in T1 and T2 concerning the QoL, self-efficacy and psychological well-being, showed that in T1 the men had higher levels of the QoL than the women in the total questionnaire ( t = 2.406; p < .05) and in the physical (t = 3.021; p < .01) and social relations (t = 1.980; p < .05) di- Table 2. Correlations. QV T1 QVf1 QVp1 QVs1 QVa1 QV T2QVf2QVp2QVs2QVa2AUT-EF B-E AUT-EF2B-E2 QV T1 - .834b .809b.629b .860b .426b .405b.412v.22 .338a .514b –.749b .358a –.452b QVf2 - .605b.394b .618b .317a .326a.314a.19 .23 .483b –.692b .346a –.362a QVp2 - .474b .496b .337a .27 .435b.08 .27 .446b –.588b .307 –.236 QVs2 - .421b .392b .386b.27 .472b.27 .300a –.335a .159 –.313a QVa2 - .349a .345a.292a.14 .308a.391b –.665b .293 –.477b QV T2 - .829b.793b.485b.947b.027 –.297a .825b –.306a QVf2 - .596b.2 .740b.119 –.292a .628b –.290a QVp2 - .25 .641b.129 –.363b .739b –.149 QVs2 - .372b–.129 –.05 .404a –.393b QVa2 - –.024 –.23 .788b –.245 AUTfEF - –.543 b .1 –.084 B-E - –.291 .569b AUT-EF2 - –.316 B-E2 - Abbreviations: QVT1, total quality of life in T1; QVf1, physical quality of life in T1; QVp1, psychological quality of life in T1; QVs1, social quality of life in T1; QVa1, environmental quality of life in T1; AUT-EF, self-efficacy in T1; B-E, well-being in T1; QV T2, total quality of life in T2; QVf2, physical quality of life in T2; QVp2, psychological quality of life in T2; QVs2, social quality of life in T2; QVa2, environmental quality of life in T2; AUT-EF2, self-efficacy2; B-E2, well-being2. ap < .05. bp < .01.  E. K. DE CASTRO ET AL. Figure 1. Averages of the total QoL and its dimensions, self-efficacy and psychological well-being in T1 and T2. mensions and higher indices of psychological well-being (–2.041; p < .05). In T2, the men also had better indicators of the QoL than the women, but only in the social relations di- mension (t = 2.024; p < .05) and in the psychological well- being (t = –2.341; p < .05). There were no significant differ- ences between genders in the self-efficacy in T1 and T2. Linear regression analysis (stepwise method) showed that the only predictive variable of the QoL in T2 was the self-efficacy (T2) (β = 0.848, p < .001), which explained 71.9% of the vari- ance (R2 = 0.719, p < .001). Discussion The present study aimed to examine longitudinally (one year) the QoL, self-efficacy and psychological well-being of patients with cancer. Generally speaking, the results indicated a relative stability of these variables during the period investigated. More- over, the variables measured in T1 were not predictive of the QoL in T2, only the self-efficacy in T2. Few studies have looked at the variables investigated in this research concerning patients with cancer, and, moreover, their results are not consistent. As they were performed in cultural contexts differing from that there (Brazil), and with patients at different stages of the disease and treatment (Kreitler, Peleg, & Ehrenfeld, 2006; Rottman, Dalton, Christensen, Frederiksen, & Johansen, 2010), the results displayed here are not fully com- parable with those found in the international literature. The very concept of the QoL, besides being subjective, indicates that it is related to the environment in which the subject is inserted, as it takes into account the cultural requirements of the location (Fleck et al., 2000). The participants of this study, all attended to free of charge by the Brazilian Unique Health System2, were characterized by poor schooling and by the heterogeneity of the types of cancer diagnosed. According to Sprangers et al. (2000), the poor school- ing may lead the subjects to have difficulty in understanding and evaluating their own QoL. It was also found in the com- parative biosociodemographic data between T1 and T2 that the number of patients with metastasis increased, which indicates that the disease, at least for this patient group, was not con- trolled. Considering this issue, the stability of the levels of the QoL, self-efficacy and psychological well-being can be under- stood to be a positive result, as, for at least part of these patients, their state of health was not better in T2 than in T1. The significant correlations observed between the QoL, self- efficacy and psychological well-being are congruent with the result of the stability of these variables in the period of one year. These findings corroborate other studies (Kreitler, Peleg, & Ehrenfeld, 2006; Campbell et al., 2004; Rottman, Dalton, Chris- tensen, Frederiksen, & Johansen, 2010) which found a positive association between self-efficacy, psychological well-being, the QoL and mental health. Thus, self-efficacy is associated with better results in health, as already found in studies with patients with other types of chronic disease (Scholz, Gutiérrez-Doña, Sud, & Schwarzer, 2002). The significant correlations between the QoL and psycho- logical well-being are also theoretically relevant and expected, as patients who perceive their life as having greater quality would be happier. However, one’s attention is drawn to the fact that in T2 the correlation between psychological well-being and the psychological dimension of the QoL was not significant. One hypothesis for this result is that, perhaps, with the adapta- tion of the patients to coping with the disease, they perceive their lives as having a reasonable psychological QoL, consider- ing their suffering and physical limitations, but do not feel “happy” with this. On the other hand, psychological well-being was correlated in T2 with the physical and environmental di- mensions of the QoL possibly because these patients are more concerned with their disease and with their capacity to adapt to the environment than with their feelings (psychological dimen- sion). Other issues could also be related to the QoL and psy- chological well-being and may be interfering in the non-corre- lation with the psychological dimension in T2, as the social support perceived, for example. Future studies will need to study this issue in greater depth. One’s attention is also drawn to the differences found in the levels of the QoL and psychological well-being between men and women, especially in T1. For Kwan et al. (2010), the psy- chosocial consequences of cancer is greater for younger than older women, which can have an impact on their QoL. How- ever, when dealing specifically with the QoL and psychological 2In Brazil, access to health services is universal (Ministry of Health, 2010). However, in practice, due to the difficulty of accessing these services and the precariousness of the attendance in certain sectors, the poorest segment of the population use them, whereas the middle and up er classes usually opt for private health plans. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 307  E. K. DE CASTRO ET AL. well-being, there is no evidence which explains these differ- ences in patients with cancer. Nevertheless, the study of Mrus, Williams, Tsevat, Cohn and Wu (2005), performed with HIV positive patients found that women had a poorer QoL than men, similar to the data of the present study. One possible interpreta- tion of the results of this study may be related to the psycho- logical implications of chemotherapy treatment for women, which produces important collateral effects that affect espe- cially the female identity, as is the case of alopecia (hair loss). Hair is associated with the feeling of the woman’s self-concept, and its loss not only generates changes in her body image, but also alters her social behavior (Münstedt, Manthey, Sachsse, Vahrson, & Changes, 1997). Besides chemotherapy, some types of surgery also have an impact on the self-image, the female identity and possibly on her QoL, as is the case of mastectomy for treatment of breast cancer or hysterectomy for the treatment of cancer of the uterus (Silva, 2008). Thus, the corporal trans- formation caused by the disease and by the treatment in the woman may be stronger than in the man, leading to a reduction of her social contact and, consequently, of the quality of her social life. In this respect, bearing in mind that the participants of the study included several women with breast cancer, a type of neoplasia directly related to female issues, the gender differ- ences found here may be due to this reason. The fact that we did not find any significant differences in self-efficacy between men and women seems to make sense as it can be considered to be a personal resource particular to each subject (Bandura, 1997, 2001). Self-efficacy, according Ban- dura, provides indicators about the individual’s long-term ad- aptation, including regarding his/her health. In this respect, it is possible to instigate psychological interventions in the context of health which can aid the patients to adapting to and coping with the disease (Rottman, Dalton, Christensen, Frederiksen, & Johansen, 2010). Another result which is worthy of note is the difference found between male and female patients in T1 and T2 in the quality of social life, indicating better results for men. Taking into account that the woman’s self-image can be greatly im- pacted by the treatment (Münstedt, Manthey, Sachsse, Vahrson, & Changes, 1997), it is possible that the poor quality of social life of these women is related to the shame or fear of being seen without hair or with the body mutilated. For the man, the loss of hair is regarded as normal, as when they get old they become bald. This may be contributing to a difference in the QoL be- tween the genders to the extent that the women end up reducing their social contact. Although the study has shown that the men also perceived themselves with better psychological well-being in T1 and T2 than the women, in the other variables this difference was not significant. This data indicates that the men were close in the levels of the QoL and self-efficacy to the women, although some differences also remained. It may be that men and women assimilate the diagnosis and treatment of cancer at different times, and so with the passage of time their well-being and QoL could be getting closer to each other. The participants of this study were young and may be part of a group of patients especially affected by a chronic disease such as cancer (Kwan et al., 2010; Semiha, Can, Durna, & Aydiner, 2008), as they are at the apex of their life (career development, forming a family, etc.). Thus, the impact of the cancer upon their QoL may also be particularly important. However, these findings may be not applied for older patients. Future studies with Brazilian samples will be able to compare the existence of differences in the QoL of patients who are young, middle-aged and senior citizens diagnosed as having cancer. The findings of this study showed a close relationship be- tween the QoL, perception of self-efficacy and psychological well-being, and that in the period of one year they remained relatively stable in the participants of this study. Moreover, the differences found between men and women indicate possible psychological vulnerability of women regarding the disease. Considering that cancer is a disease which can greatly alter the QoL of patients, it is necessary to make further studies starting from these gender differences. Investigating issues related to the performance of the female and male role in the situation of a chronic disease regarding the family and society becomes necessary in order to understand the phenomenon raised ere more fully. This study has limitations, such as, for example, the hetero- geneity of the sample related to the types of cancer, particulari- ties which could not be assessed in this study. Nevertheless, the results found here offer a first portrait of the situation of young Brazilian patients with cancer, and can be used as a point of departure for further studies about the subject. REFERENCES Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: W. H. Freeman and Company. Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 1-26. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1 Bertan, F. C., & Castro E. K. (2009). Quality of life and câncer: A systematic literature review. Psico, 40, 366-372. Campbell, L. C., Keefe, F. J., Mckee, D. C., Edwards, C. L., Herman, S. H., Johnson, L. E., Colvin, O. M., McBride, C. M., & Donatucci, C. F. (2004). Prostate cancer in African Americans: Relationship of pa- tient and partner self-efficacy to quality of life. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 28, 433-444. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.02.020 Fleck, M., Louzada, S., Xavier, M., Chachamovich, E., Vieira, G., Santos, L., & Pinzon, V. (2000). Application of the Portuguese version of the abbreviated instrument of quality life WHOQOL-bref. Revista de Saúde Pública, 34, 178-183. doi:10.1590/S0034-89102000000200012 Goldberg, D. P. (1978) Manual for the general health questionnaire. Windsor: National Foundation for Educational Research;. Gouveia, V., Chaves, S. S. da S., Oliveira I. C. P. de, Dias, M. R., Gouveia, R. S. V., & Andrade, P. R. de. (2003). The use of the GHQ-12 in a general population: a study of its construct validity. Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa, 19, 241-248. doi:10.1590/S0102-37722003000300006 Howell, R. T., Kern, M. L., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2007). Health benefits: Meta-analytically determining the impact of well-being on objective health outcomes. Health Psychology Review, 1, 83-136. doi:10.1080/17437190701492486 Kreitler, S., Peleg, D., & Ehrenfeld, M. (2006). Stress, self-efficacy and quality of life in cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology, 4, 329-341. Kwan, M. L., Ergas, I. J., Somkin, C. P., Charles, P., Quesenberry, C. P. Jr., Alfred, Neugut, A. I., Hershman, D. L., Mandelblatt, J., Pelayo, M. P., Timperi, A. W., Miles, S. Q., & Kushi, L. H. (2010). Quality of life among women recently diagnosed with invasive breast cancer: The Pathways Study. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, 123, 507-524. doi:10.1007/s10549-010-0764-8 Mayo, N. E., Moriello, C., Asano M., Van der Spuy, S., & Finch, L. (2011). The extent to which common health-related quality of life indices capture constructs beyond symptoms and function. Quality of Life Research, 20, 621-627. doi:10.1007/s11136-010-9801-7 Montazeri, A. (2008). Health-related quality of life in breast cancer Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 308  E. K. DE CASTRO ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 309 patients: A bibliographic review of the literature from 1974 to 2007. Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research, 29, 27-32. Mrus, J. M., Williams, P. L, Tsevat, J., Cohn, S. E., & Wu, A. W. (2005). Gender differences in health related quality of life in patients with HIV/Aids. Quality of Life Research, 14, 479-491. doi:10.1007/s11136-004-4693-z Münstedt, K., Manthey, N., Sachsse, S. & Vahrson, H. (1997). Changes in self-concept and body image during alopecia induced cancer che- motherapy. Supportive Care in Cancer, 5, 139-143. doi:10.1007/BF01262572 Perkins, H. Y., Baum, G. P., Taylor, C. C., & Basen-Engquist, K. M. (2009). Effects treatment factors, comorbidities and health-related quality of life on self-efficacy for physical activity in cancer survi- vors. Psycho-Oncology, 18, 405-411. doi:10.1002/pon.1535 Ramachandra, P., Booth, S., Pieters, T., Vrotsou, K., & Huppert, F. A. (2009). A brief self-administered psychological intervention to im- prove well-being in patients with cancer: Results from a feasibility study. Psycho-Oncology, 18, 1323-1326. doi:10.1002/pon.1516 Rottman, N., Dalton, S. O., Christensen, J., Frederiksen, K., & Johansen, C. (2010). Self-efficacy, adjustment style and well-being in breast cancer patients: A longitudinal study. Quality of Life Re- search, 19, 827-836. doi:10.1007/s11136-010-9653-1 Seidl, E. M. F., & Zannon, C. M. C. (2004). Quality of life and health: Conceptual and methodological issues. Cadernos de Saúde Pública, 20, 580-588. doi:10.1590/S0102-311X2004000200027 Semiha, A., Can, G., Durna, Z., & Aydiner, A. (2008). The quality of life and self-efficacy of Turkish breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. European Journal of Onc ology Nu rsing, 12, 449-456. doi:10.1016/j.ejon.2008.07.006 Scholz, U., Gutiérrez-Doña, B., Sud, S., & Schwarzer, R. (2002). Is general self-efficacy a general construct? Psychometric findings from 25 countries. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 18, 242-251. doi:10.1027//1015-5759.18.3.242 Schwarzer, R., Boehmer, S., Luszczynska, A., Mohamed, N. E., & Knoll, N. (2005). Dispositional self-efficacy as a personal resource factor in coping after surgery. Personality and Individual Differences, 39, 807-818. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2004.12.016 Silva, L. C. (2008). Breast cancer and psychological suffering: Female- related aspects. Psicologia em Estudo, 13, 231-237. doi:10.1590/S1413-73722008000200005 Sprangers, M. A. G., Regt, E. B., Andries, F., Van Agt, H. M., Boer, J. B. de., Foets, M., Hoevmans, N., Jacobs, A. E., Kempen, G. I., Miedema, H. S., Tijhuls, M. A., & De Haes, H. C. (2000). Which chronic conditions are associated with better or poorer quality of life? Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 53, 895-907. doi:10.1016/S0895-4356(00)00204-3 Teixeira, M. A., & Dias, A. C. (2005). Psychometric properties of Por- tuguese version of Perceived self-efficacy by Ralph Schwarzer. Em Resumos do II Congresso Brasileiro de Avaliação Psicológica [CD]. Instituto Brasileiro de Avaliação Psicológica (Org.): Gramado: IBAP.

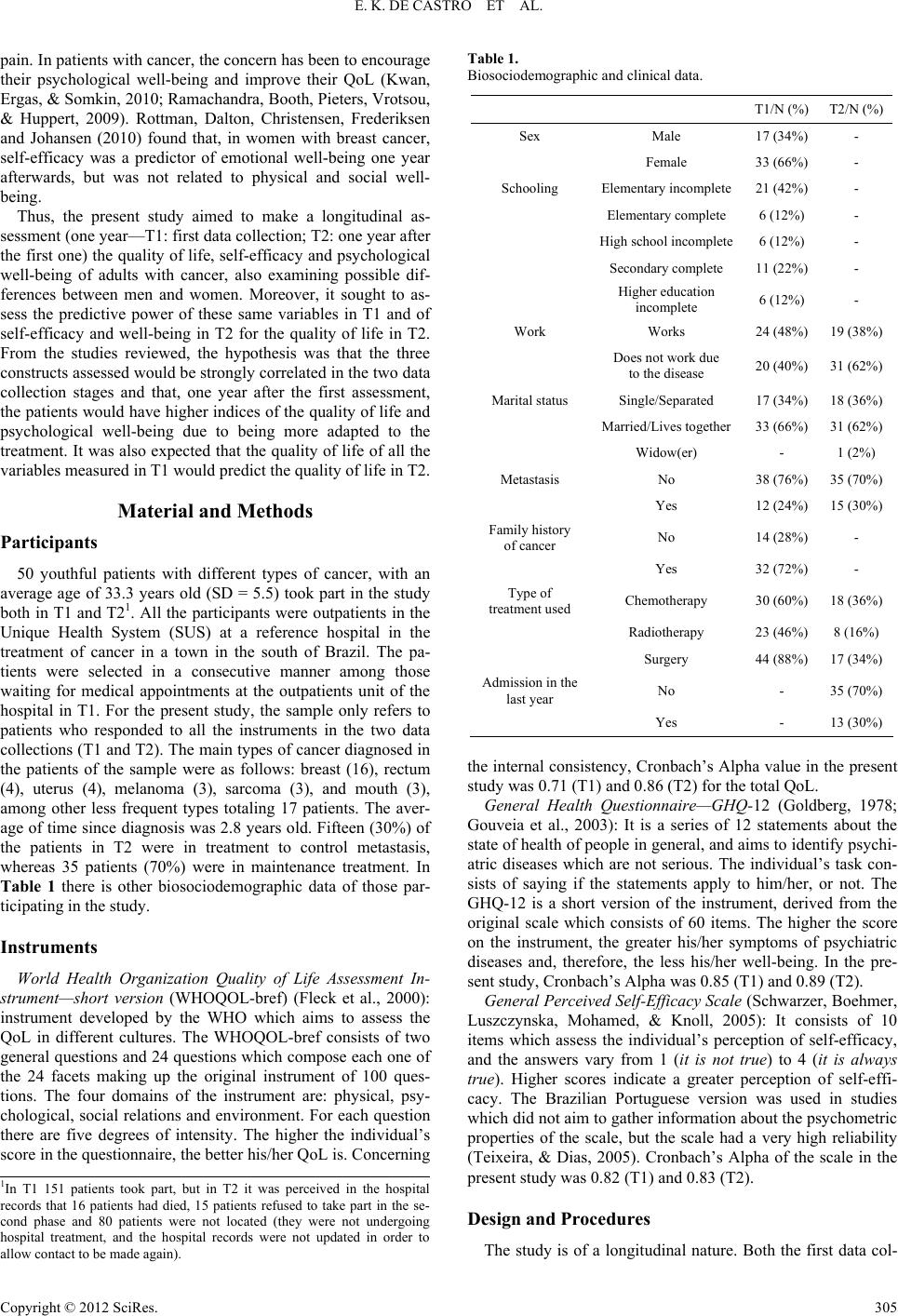

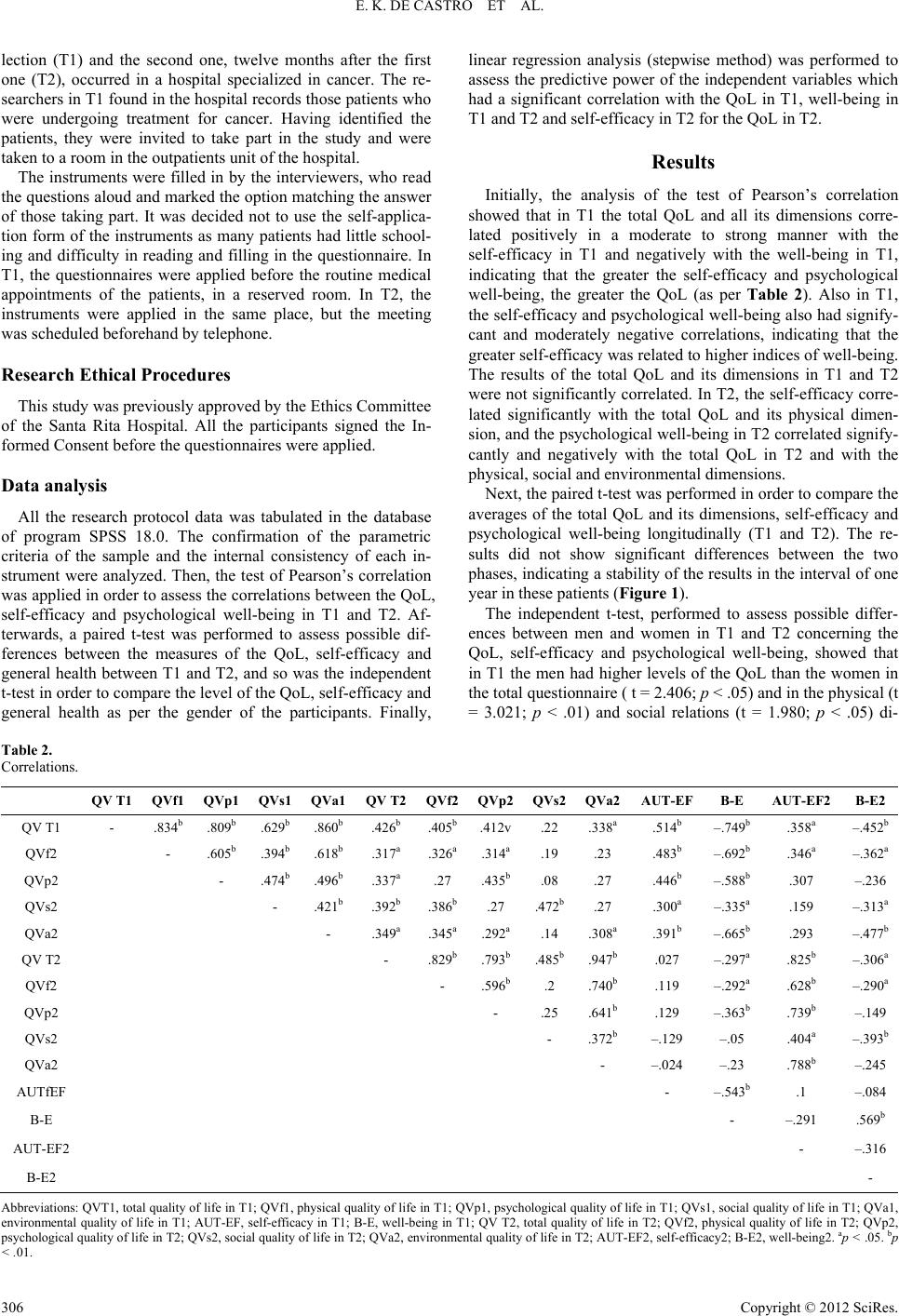

|