Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

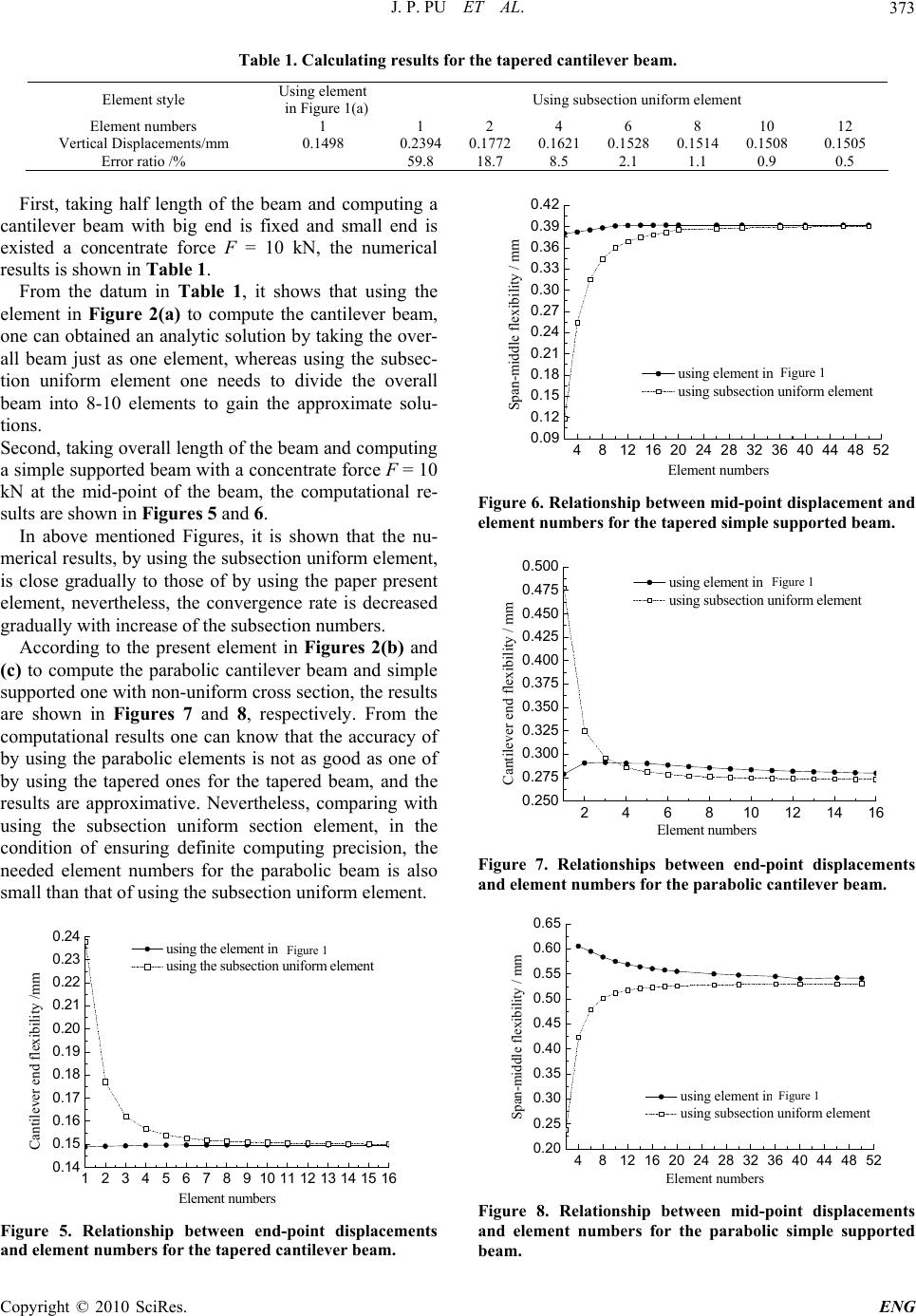

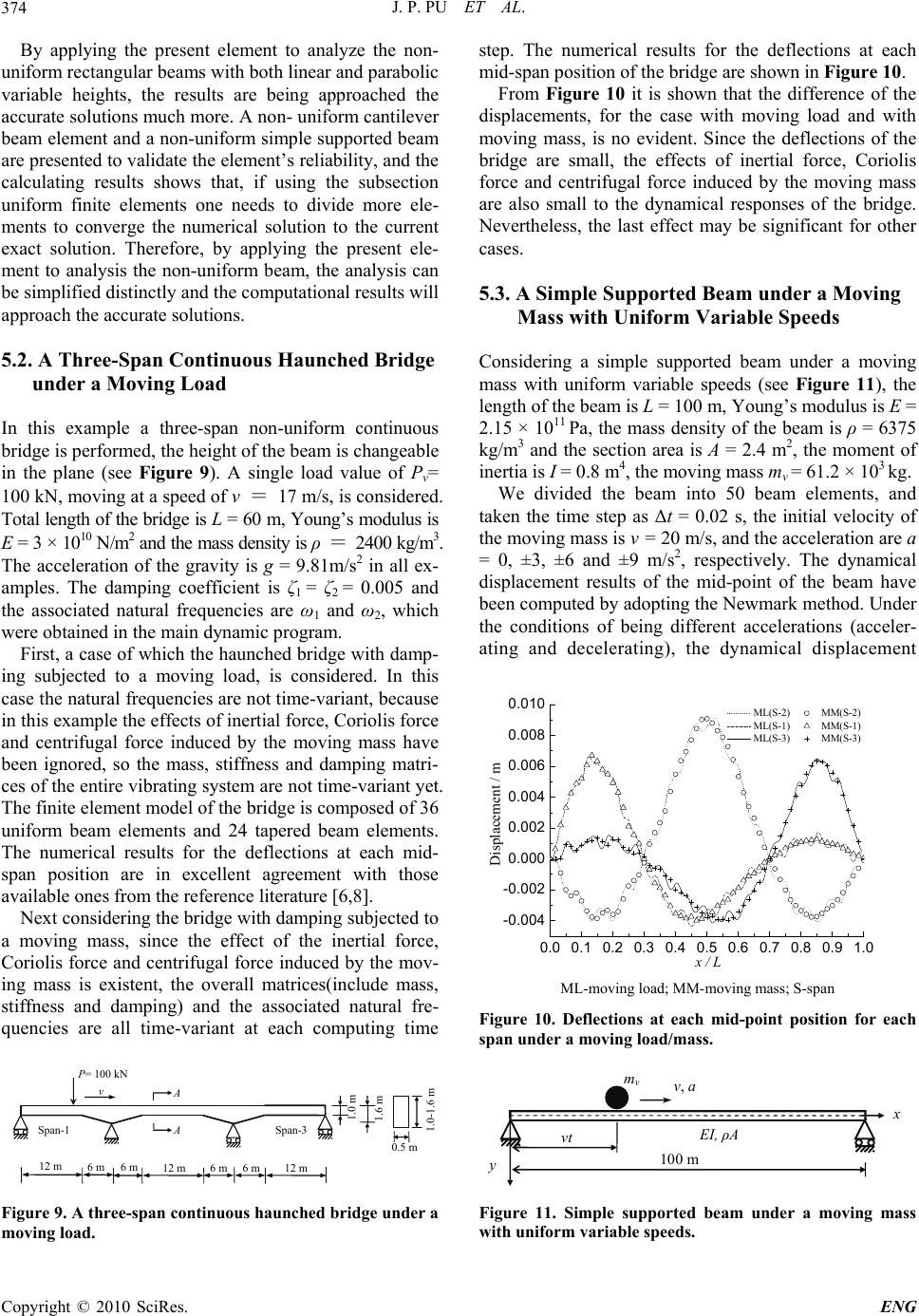

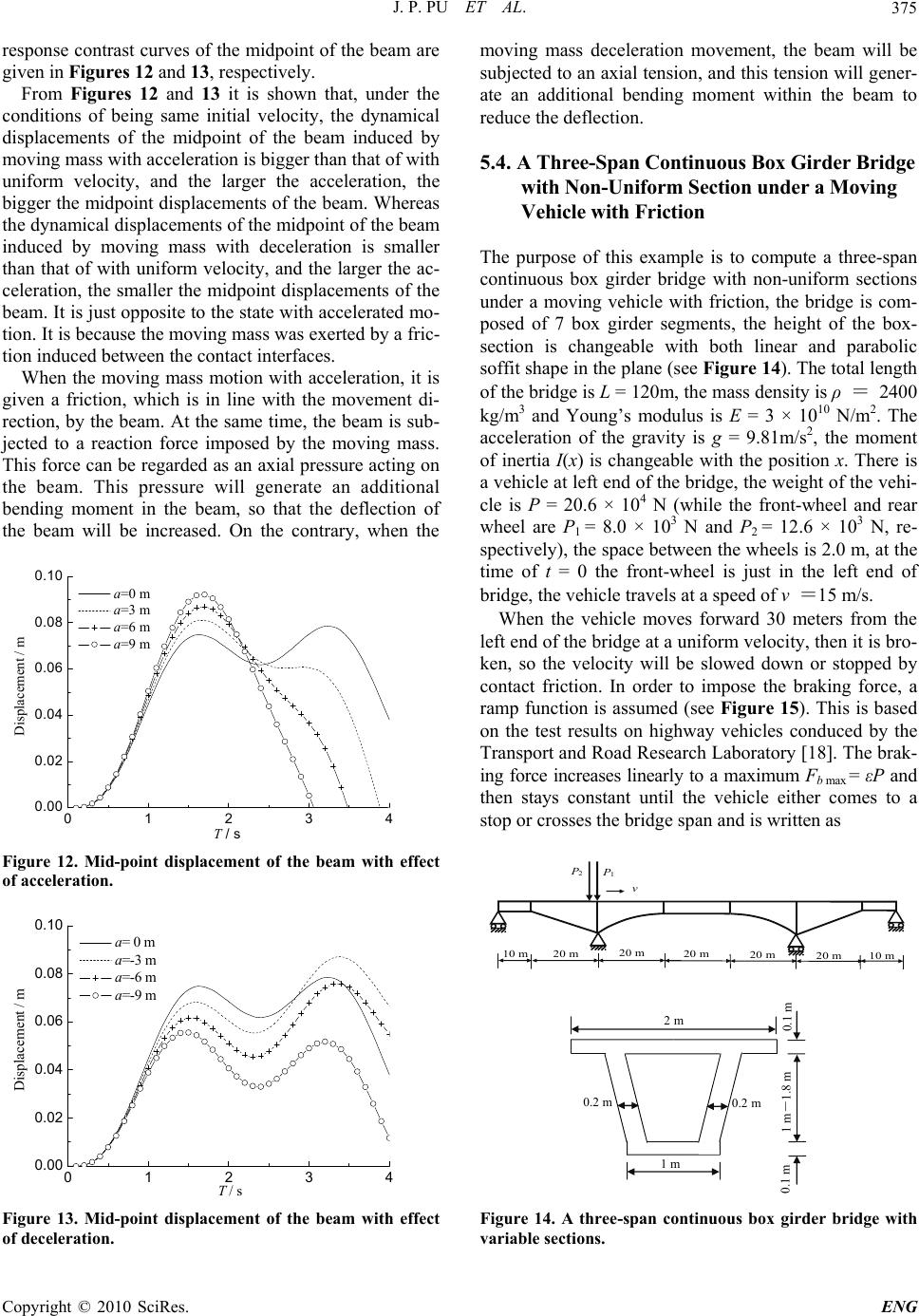

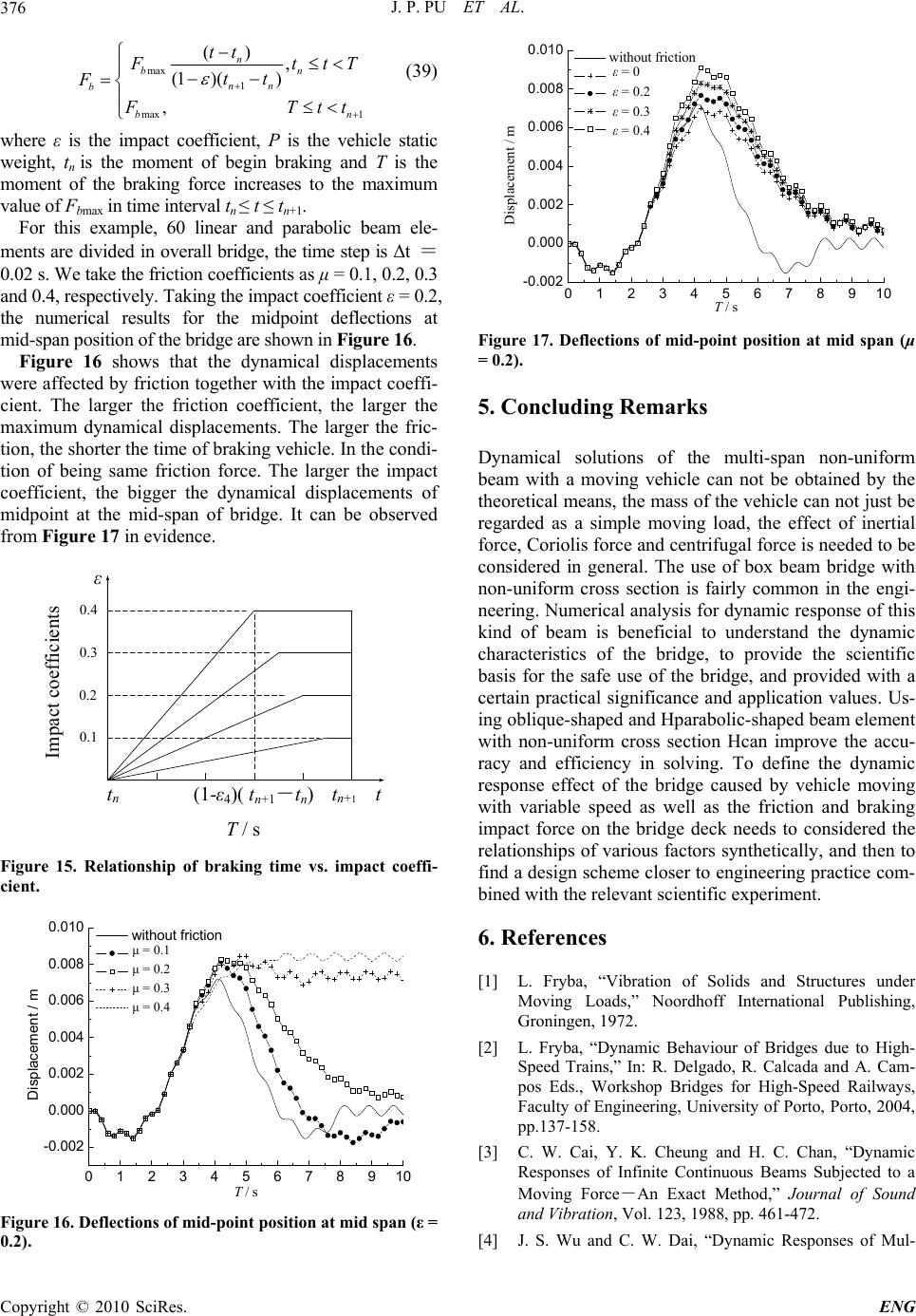

Engineering, 2010, 2, 367-377 doi:10.4236/eng.2010.25048 Published Online May 2010 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/eng) Copyright © 2010 SciRes. ENG 367 Numerical Calculation of Dynamic Response for Multi-Span Non-Uniform Beam Subjected to Moving Mass with Friction Junping Pu, Peng Liu College of Civil Engineering & Architecture, Zhejiang University of Technology, Hangzhou, China E-mail: pjp@zjut.edu.cn, pliu85@126.com Received January 19, 2010; revised February 20, 2010; accepted February 2, 2010 Abstract In order to simulate the coupling vibration of a vehicle or train moves on a multi-span continuous bridge with non-uniform cross sections, a moving mass model is used according to the Finite Element Method, the effect of the inertial force, Coriolis force and centrifugal force are considered by means of the additive ma- trices. For a non-uniform rectangular section beam with both linear and parabolic variable heights in a plane, the stiffness and mass matrices of the beam elements are presented. For a non-uniform box girder, Romberg numerical integral scheme is adopted, each coefficient of the stiffness matrix is obtained by means of a nor- mal numerical computation. By applying these elements to calculate the non-uniform beam, the computa- tional accuracy and efficiency are improved. The finite element method program is worked out and an entire dynamic response process of the beam with non-uniform cross sections subjected to a moving mass is simu- lated numerically, the results are compared to those previously published for some simple examples. For some complex multi-span bridges subjected to some moving vehicles with changeable velocity and friction, the computational results, which can be regarded as a reference for engineering design and scientific research, are also given simultaneously. Keywords: Dynamic Response, Multi-Span Beam, Non-Uniform Section, Friction, Braking Force 1. Introduction Continuous beams are general statically indeterminate structures, and have broad applications in civil engi- neering, mechanism, navigation engineering and so on. Multi-span continuous bridges have been widely used in highway and railway, there is a great deal of merit for the structures, for example, their exterior is beau- tiful, the holistic structures’ stability is well, the spacial span is bigger and on which vehicles can plac- idly pass over. It is of great importance to study the dynamic characteristic of the bridge under moving mass for engineering design and scientific research. Many engineers and scientists have contributed to the solution of the problem with their innovations, and still the subject draws considerable attention from re- searchers by now. Fryba [1,2] had given an exact so- lution on dynamic responses of the simple supported beam and continuous beam under moving load. Cai, Cheung and Chan [3] investigated the dynamic re- sponses of the infinite continuous beam subjected to a moving force by using the mode superposition method to get an exact solution. However, for a great number of bridge structures in engineering practice, it can not be simply regarded as a perfect state, so their theoretic solutions are not existent in general. Thus, among the numerical methods the finite element method becomes an ideal approximate approach to solve this kind of problems [4-12]. Wu [13,14] performed the dynamic analysis of an inclined beam and a flat plate due to moving loads, and presented the moving mass element by taking account of the effect of inertial force, Corio- lis force and centrifugal force induced by the moving mass. Form mentioned literatures, it is shown that, for the multi-span continuous non-uniform beam, one used a moving load model to obtain the numerical  J. P. PU ET AL. 368 results in general, but did not consider the effect of inertial force, Coriolis force and centrifugal force. Some numerical examples dealt with above effect but just analyzed the simple uniform beam. This paper has been performed some complex problems (include multi-span non-uniform beam with moving mass). For a non-uniform rectangular section beam with both linear and parabolic variable heights in a plane, the stiffness and mass matrices of the beam elements have been de- ducted. For a non-uniform box girder which can be widely used in engineering structures, since the integral formula of stiffness matrix is extremely complex, it is difficult to write down the expression of the stiffness coefficients, so Romberg numerical integral scheme is adopted. Each coefficient of the stiffness matrix can be obtained by means of a normal numerical computa- tion. For some complex multi-span bridges subjected to some moving vehicles with changeable velocities and frictions, numerical results of dynamic responses are also obtained, which can be regarded as a reference for engineering design and scientific research. 2. Forced Vibration Differential Equation of Euler-Bernoulli Beam Forced vibration differential equation of Euler-Bernoulli beam in plane bending with damping takes the form ),()()( )()( 2 2 2 3 2 2 2 2 2 2 txf t y xc t y xm xt y xI x c x y xEI xs (1) where, the mass per unit length of the beam is m(x) = ρA, while ρ is the material density and A is the area of the cross section of the beam, c s is damping coefficient of strain rate, c(x) is damping coefficient of displacement rate. When a concentrate excited force P(t) was exerted at xi =vt of the beam, the force can be expressed, by using the Dirac Delta function δ, as (,) ()() i f xtPtxvt (2) where v is the moving velocity. When a moving mass M with the constant velocity moved on the beam, the action force on the beam can be considered as a common effect of the gravity and inertia force according to reference literature [15]. )()],([),(vtxtvtygMtxf (3) Thus the formula (1) will be a set of systems of second order differential equations with time-variant coefficient, it needs to be solved by means of numerical method. Lee’s investigation indicated, in literature [16,17], that when the moving mass M with the constant velocity moved on the Euler-Bernoulli beam, including the grav- ity and inertia force induced by moving mass M, one still needs to consider the effect of Coriolis force and cen- trifugal force on the beam, that is )()],( ),(2),([),( 2vtxtvtyv tvtyvtvtygMtxf (4) Considering the contact friction between the wheels and the beam, a axial force X(ξ,t) should be exerted on the beam, thus the action force on the beam can be ex- pressed as follows )( ),()],( ),(2),([ ),( 2 x tXtyv tyvtygM txf (5) When a moving vehicle has a brake on the bridge at a moment tn, if the contact friction is big enough, the vehi- cle will stop at moment tn+1, the axial force X(ξ,t) can be expressed as 0 ),( MatX , (6) )0( n tt )(),( 0 agMtX , (7) )(1 nn ttt 0),( tX . (8) )( 1 n tt where a0 is the initial acceleration of the vehicle, μ and g represent the friction factor and that of gravity, respec- tively. If the moving vehicle does not brake on the bridge at any moment, the axial force X(ξ,t) will be expressed as 0 ),( MatX (9) )0(t The position ξ of the moving vehicle at the bridge can be expressed as follows (see Figure 1) 2 000 5.0 tatvx , (10) )( n tt 2 )(5.0)( nnnnn ttattvx )(1 nn ttt (11) nnn avx2/ 2 . (12) )( 1 n tt where v0 is the initial velocity, the position, velocity and acceleration at moment tn are, respectively, 2 000 5.0 nnn tatvxx , (13) nn tavv 00 , (14) gaan 0. (15) 3. Discrete Model of Vibration Equations under Moving Mass According to the finite element method, the forced vibration differential equation of Euler-Bernoulli beam in plane bending with damping can be written, in matrix form, as follows )()()()( tttt FKyyCyM (16) where ),(),(),()( tttt av XPPF (17) Copyright © 2010 SciRes. ENG  J. P. PU ET AL.369 n t t n x P 00 ,av nn av, 0 0,0 11 nnav nnnn avtt/ 1 Figure 1. The position ξ of the moving vehicle at the beam. The action force of the vehicle on the beam can be expressed by the nodal load vector F(t), which is composed of the gravity Pv i(ξ, t)=Mv ig, and the mass force Pa i (ξ, t) (include inertia force, Coriolis force and centrifugal force) of the vehicle, as well as the axial action force X i(ξ, t), while i=1,n denotes the number of moving mass Mv i. Due to the location of each moving mass was con- tinuously transformed with time, while the moving mass passed along each beam element, the action of the gravity, at current position in each time interval Δt, can be distributed to the element nodes to become the element nodes’ forces by using an interposition function. For Euler-Bernoulli beam element, one can adopt cubic Hermite interposition function of two-nodes, Nj(ξ), while j = 1,6, to get gravity load Pv e(ξ, t), which is expressed as 654321 ),( vvvvvv e vFFFFFFt P (18) where )6,,1(),()(),( jtPNtF i vj j v (19) The action of the axial action force X i(ξ, t), at cur- rent position in each time interval Δt, can also be dis- tributed to the element nodes. Now just the axial action was considered, the shear and moment were ignored. 0000),(41 XXt eX (20) where (,)() (,)(1,4) ji j XtNXtj (21) The mass force Pa i(ξ, t) can be discretized according to the form of element displacement interposition func- tion y = ΣNjyj= Ny (j = 1,6). Consequently, one can ob- tain the additive moving mass matrix ma(t), moving damping matrix ca(t) and moving stiffness matrix ka(t) from Equation (22) ykycymINP aaa e at ),( (22) where I is the unit matrix, Pa e(ξ, t) is the equivalent nodal force vector inducing by the moving mass force, the shape function vector is a diagonal matrix N=diag(N1(ξ) N2(ξ) N3(ξ) N4(ξ) N5(ξ) N6(ξ)) . A detailed deduc- ing process can be referenced in literature [13]. Instituting the additive moving mass matrix m a(t) and stiffness matrix ka(t) into the entire mass matrix M and stiffness matrix K of the original beam structure, respectively, the new entire matrix)(tMand ()t K are formed and are time-variant. )()( tt a mMM (23) () () a tKKkt (24) The overall damping matrix C of the beam is de- termined by using the theory of Rayleigh damping, adding the additive damping matrix ca(t) into C, the new entire damping matrix ()tCcan be gotten by for- mula (25) )()()()()()( tttttt a cKMC (25) where )/()(2)( 2 1 2 2122121 t (26) )/()(2)(2 1 2 21122 t (27) The coefficients α(t) and β(t) are also time-variant with changing of the natural frequencies ω1 and ω2 of the beam structure at each time steps. Finally, according to Equation (28) one can numerically compute an entire system of vibration equation with Newmark direct inte- gration method or with Wilson-θ method. )()()()()()()( ttttttt FyKyCyM (28) where the load vector()t F includes the gravity load of the moving vehicle Pv(ξ, t) and the axial force X(ξ, t) as well as the adscititious load P(t) induced by other cau- sations. 4. Stiffness and Mass Matrices of Non-Unform Beam Elements 4.1. Non-Uniform Rectangular Cross Section For a non-uniform rectangular section beams with both linear and parabolic variable heights in a plane, the stiff- ness and mass matrices are deducted, respectively. So one can analyze the non-uniform beam according to a convenient mode (see Figure 2). According to Figures 2(a), (b) and (c), the cross sec- tion height, area and the moment of inertia of the beam can be given by expressions (29)-(31), respectively. 01 3 01 1 1/ hx hh Ix bhh 12 (29) h 0 h 1 h(x) l h 0 h 1 h(x) l h 0 h 1 h(x) l (a) (b) (c) Figure 2. Variable cross-sectional beam elements. Copyright © 2010 SciRes. ENG  J. P. PU ET AL. 370 01 3 01 1 1/ hx hh Ix bhh 12 (30) 01 3 01 111 111 hx hh Ix bhh /12 3 l (31) where h0 and h1 are beginning and end height of the beam elements with non-uniform cross sections, respectively. ξ=x/l, while l is the length of the beam element and b is the width of the cross section with rectangular form. The element stiffness and mass matrices can be ob- tained, respectively, from T 0d l eEI xx KB B (32) lxxAV 0 T T V ed)(d e NNNNM (33) where B=∂2N / ∂x2, while EI(x) and A(x) are the flexural stiffness and the cross section area of the beam, respec- tively, which are changeable with the height changing of the cross section. Adopting above-mentioned non-uniform beam models and an integral procedure is worked out, the coefficients of the elemental stiffness and mass matrices, k ij and mij, can be obtained as follows 4.1.1. Stiffness Matrix Coefficients with Linear Varable Heights (Figure 2(a)) 1144140 1 32 23 222555001011 32232 2335001011 32232 26560010 11 32 23 330010 11 3 360 0 ()/2 (7337) / 20 (522) /20 (225)/ 20 (11522)/ 60 (4 kk kEbhhl kkkEbhhhhhh kkEbhhhhhhl kkEbhhhhhhl kEbhhhhh hl kEbhh 223 101 1 322 3 66001011 12131516 2434 45 46 4)/60 (22511) / 60 0 hhh hl kEbhhhhh hl kkkkkkkk 4.1.2. Mass Matrix Coefficients with Linear Variable Heights (Figure 2(a)) 110 1 1401 220 1 2 23 01 250 1 2 26 01 3 33 01 2 35 01 3/12 /12 (23/ 5)/ 7 (/28/60) 9() /140 (/ 60/ 70) (/168/ 280) (/ 70/ 60) mblhh mblhh mhhbl mh h bl mhhbl mhhbl mh hbl mhhbl 3 360 1 4401 55 ()/280 3/12 (3 m hhbl mblhh mh 01 2 56 01 3 66 01 12 13 15 1624344546 /52 )/7 (/60/28) (/ 280/168) 0 hbl mh h bl mhh bl mmmmmmmm 4.1.3. Stiffness Matrix Coefficients with Parabolic Variable Heights (Figure 2(b), h0>h1) 11 441401 32 23 2225550010 11 3223 2 23350010 11 (2)/3 (37423992) / 210 (26302128) /210 kkkEbh hl kkkEbh hhhh h kkEbhhhhhh l 3 l 2 l 3223 26560010 11 32 23 33001011 322 3 360010 11 322 3 660010 11 12131516 24 34 4546 (11121864) / 210 (37463324) /420 (1514932) / 420 (7102796) /420 0 kkEbhhhhhh kEbhhh hhhl kEbh hhhhhl kEbh hh hhhl kkkkkkkk 4.1.4. Mass Matrix Coefficients with Parabolic Varable Heights (Figure 2(b), h0>h1) 1101 140 1 220 1 2 230 1 250 1 2 26 01 3 3301 35 0 1916/105 1124/ 210 (93077424)/ 45045 (21592560)/ 90090 (35518032)/ 90090 (373/36036928/45045) (173256)/ 45045 (103/ 120 mblhh mblhh mhhbl mhhbl mhhbl mhhbl mhhbl mh 2 1 3 360 1 4401 55 0 1 2 56 01 3 660 1 12131516 24 34 45 46 1216/ 715) (391896 )/180180 6/21 (7194858 )/15015 (19/ 200292/ 2145) (31112 )/15015 0 hbl mhhbl mblhh mhhbl mhh bl mhhbl mmmmmmmm 4.1.5 Stiffness Matrix Coefficients with Parabolic Variable Heights (Figure 2(c), h0<h1) 11441401 32 23 2225550010 11 3223 2 23350010 11 32232 2656001011 322 330010 11 (2)/ 3 (92394237) / 210 (64181211)/ 210 (28213026) / 210 (96 27107 kk kEbhhL kkkEbhhhhhh kkEbhhhhhhl kkEbhhhhhh l kEbhhh hhh 3)/420l 3 l Copyright © 2010 SciRes. ENG  J. P. PU ET AL.371 l 322 3 36001011 32 23 66001011 12131516 24 34 4546 (3291415) /420 (24334637)/ 420 0 kEbhhh hhhl kEbhhhhhh kkkkkkkk 4.1.6. Mass Matrix Coefficients with Parabolic Varable Heights (Figure 2(c), h0<h1) 110 1 140 1 220 1 2 23 01 2501 2 26 01 3 330 1 35 01 6/21 2411/ 210 (4858719 )/15015 (92/ 214519/ 2002) (80323551)/ 90090 (16/ 715103/12012) (11231 )/15015 (928/ 45045373/ mblhh mblhh mhhbl mhh bl mhhbl mhh bl mhhbl mhh 2 3 360 1 440 1 36036) (896391)/180180 1619 /105 bl mhhbl mblhh 550 1 2 560 1 3 6601 12 13 151624344546 (74249037)/45045 (25602159)/ 90090 (256173)/ 45045 0 mhhbl mhhbl mhhbl mmmmmmmm 4.2. Non-Uniform Box Girder Section The box section is shown in Figure 3 with an up bottom width of B and a down bottom width of D. The thick- nesses of both up and down bottom board are T. The ventral shield thickness is C, and the section height of the box girder is h(x). The centroid distance w from cen- troidal axis z to z′ axis of self-defined is 2 () (2)() 0.5() 2()( 4) () ChxDCThxBD T ChxBDCT wx 2 (34) So the area and moment of inertia can be denoted by a section height h(x) and a centroid distance w(x) as fol- lows ()2()(4 ) A xChxBDCT (35) 2 3 2 33 2 () 2 1 () () 6 () 2()() 2 11 (2) 12 12 (2)() () 2 T BTw x IxChx T hxT ChxTwx BTDCT T DCThxwx (36) Hypothesis that using a linear and parabolic variable mode such as Figure 2, the beam height h(x) of box girder element can also be denoted by formula 29, 30 and 31. Since w(x) is a composite function of h(x), so the moment of inertia I(x) is also a very complex composite function, moreover have some rational fractions in it. It is difficult to get a fixed form integral result by a manual calculation, so Romberg numerical integral scheme is adopted in this paper. The numerical integral precision is controlled to be 10-6. Each coefficient of the stiffness matrix of non-uniform section box girder element can be obtained by means of Formula (37). 2 2 22 0 () () () lj i ij dN x dN x kEIx dx dx dx (37) When deducing the mass matrix of non-uniform sec- tion box girder element, since the area function A(x) is relatively simple, so we adopt a manual calculation fashion and the fixed form integral result is gotten. Ob- serving Formula (35), and comparing the area formula of a rectangular cross section, a superfluous item (B+D-4C) T is found. These coefficients are constants. Form the general Expressions (33) of mass matrix, it is easily known that the mass matrix of non-uniform section box girder element is gotten, as long as substituting the pa- rameter b into 2C and adding an item (such as Formula (38)) in mass matrix of rectangular cross section beam element. 0 (4) lT e M BD CTNNdx (38) For referring and using conveniently, based on be- fore-mentioned three non-uniform section modes, the deduced results for all elements mij of mass matrix of box girder element are enumerated as follows. 4.2.1. Mass Matrix Coefficients of the Box Girder with Linear Variable Heights (Figure 2(a)) 1101 1401 440 1 220 1 2 230 1 250 1 2 2601 32 4/6 4/6 32 4/6 210 3134/35 157114/210 94 276 13 mlChhTBDC mlChhTBDC mlChhTBDC mlChh TBDC mlChhTBDC mlChhTBDC mlChhTB 3 3301 2 350 1 3 360 1 4/42 53 44/420 26 7134 /420 4/140 DC mlChhTBDC mlChhTBDC mlChhTBDC /70 0 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. ENG  J. P. PU ET AL. 372 C D B h(x) T T z y z’ w Figure 3. Geometry size of cross section of the box girder. 55 0 2 560 1 3 660 1 12 13 15 1624 344546 2310134/35 715114/ 210 3544/ 420 0 mlChhTBDC mlChhTBDC mlChhTBDC mmmmmmmm 4.2.2. Mass Matrix Coefficients of the Box Girder with Parabolic Variable Heights (Figure 2(b), h0>h1) 110 1 140 1 4401 220 1 2 230 1 25 2 1916354/105 21124354/ 210 267 4/21 293077424167314/45045 22159256047194/ 90090 2 3551 mlChh TBDC mlChh TBDC mlChhTBDC mlC hhTBDC mlC hhTBDC mlC 01 2 260 1 3 330 1 2 350 1 3 3601 8032115834/ 90090 21865 371255774 /180180 21732564294/ 45045 2 1545403255774/180180 2391 89612874 hh TBDC mlC hhTBDC mlCh hTBDC mlC hhTBDC mlC hhTBDC 55 0 2 560 1 3 660 1 1213151624 34 45 46 /180180 2 719485855774/15015 2855386447194/ 90090 2 311121434/15015 0 mlCh h TBDC mlC hhTBDC mlCh hTBDC mmmmmmmm 4.2.3 Mass Matrix Coefficients of the Box Girder with Parabolic Variable Heights (Figure 2(c), h0<h1) 220 1 2 230 1 25 0 110 1 1401 440 1 2/21 /210 /105 2 485871955774/15015 2128828515734/ 30030 2 8032 67 4 22411354 216 19354 C mlC hhTBDC mlC hhTBDC mlCh ml hhTBDC mlChhTBDC mlChhTBDC 1 3551115834/ 90090hTBDC 2 260 1 3 3301 1 350 1 360 1 55 0 2 3 2134451518594/ 60060 2 11203114304/150150 3712 1865/180180 896 /180180 2 74249037 255774 2391 12874 16 mlCh hTBDC mlC hhTBDC C mlC hhTBDC mlC hhTBDC mlh h 2 560 1 3 660 1 121315162434 45 46 / 45045 225602159/ 90090 2256173/ 45045 0 731 4 4719 4 429 4 C C TB DC mlh hTBDC mlh hTBDC mmmmmmmm 4.2.3 Mass Matrix Coefficients of the Box Girder with Parabolic Variable Heights (Fig. 2(c), h0<h1) 1101 140 1 440 1 220 1 2 230 1 25 0 2674 /21 22411354/210 2 1619354/105 2 485871955774/15015 2128828515734/ 30030 2 8032 mlChhTBDC mlChhTBDC mlChhTBDC mlC hhTBDC mlChhTBDC mlCh 1 2 260 1 3 330 1 2 350 1 3 360 1 3551115834/ 90090 2 1344 51518594 /60060 2 11203114304/150150 2 3712186555774/180180 2 896 39112874 /1 hTBDC mlCh hTBDC mlC hhTBDC mlChhTBDC mlC h hTBDC 550 1 2 560 1 3 660 1 12 13 15 1624 3445 46 80180 274249037167314/45045 22560215947194/90090 22561734294/45045 0 mlC hhTBDC mlChhTBDC mlChhTBDC mmmmmm mm h 0 h 1 h 0 5. Numerical Examples 5.1. Validation In order to demonstrate the feasibility of the present stiffness and mass element matrices, a simple example is performed, that is, a non-uniform cross section beam with the length l = 20 m, the width of the rectangular section is b = 0.2 m, the small end and the big end height are h1 = 0.1 m and h0= 0.3 m, respectively. Young’s modulus is E = 3.0 × 1010 N/m2, the concentrate load is F = 10 kN, the shape of the beam is shown in Figure 4. l F Figure 4. Shape of the beam. Copyright © 2010 SciRes. ENG  J. P. PU ET AL. Copyright © 2010 SciRes. ENG 373 Table 1. Calculating results for the tapered cantilever beam. Element style Using element in Figure 1(a) Using subsection uniform element Element numbers 1 1 2 4 6 8 10 12 Vertical Displacements/mm 0.1498 0.23940.17720.16210.15280.1514 0.1508 0.1505 Error ratio /% 59.8 18.7 8.5 2.1 1.1 0.9 0.5 First, taking half length of the beam and computing a cantilever beam with big end is fixed and small end is existed a concentrate force F = 10 kN, the numerical results is shown in Table 1. 4812 16 20 24 28 32 36 40 44 48 52 0.09 0.12 0.15 0.18 0.21 0.24 0.27 0.30 0.33 0.36 0.39 0.42 Span-middle flexibility / mm Element numbers using element in Fig.1 using subsection uniform element Figure 1 From the datum in Table 1, it shows that using the element in Figure 2(a) to compute the cantilever beam, one can obtained an analytic solution by taking the over- all beam just as one element, whereas using the subsec- tion uniform element one needs to divide the overall beam into 8-10 elements to gain the approximate solu- tions. Second, taking overall length of the beam and computing a simple supported beam with a concentrate force F = 10 kN at the mid-point of the beam, the computational re- sults are shown in Figures 5 and 6. Figure 6. Relationship between mid-point displacement and element numbers for the tapered simple supported beam. In above mentioned Figures, it is shown that the nu- merical results, by using the subsection uniform element, is close gradually to those of by using the paper present element, nevertheless, the convergence rate is decreased gradually with increase of the subsection numbers. 246810 12 1416 0.250 0.275 0.300 0.325 0.350 0.375 0.400 0.425 0.450 0.475 0.500 Cantilever end flexibility / mm Element numbers using element in Fig.1 using subsection uniform element Figure 1 According to the present element in Figures 2(b) and (c) to compute the parabolic cantilever beam and simple supported one with non-uniform cross section, the results are shown in Figures 7 and 8, respectively. From the computational results one can know that the accuracy of by using the parabolic elements is not as good as one of by using the tapered ones for the tapered beam, and the results are approximative. Nevertheless, comparing with using the subsection uniform section element, in the condition of ensuring definite computing precision, the needed element numbers for the parabolic beam is also small than that of using the subsection uniform element. Figure 7. Relationships between end-point displacements and element numbers for the parabolic cantilever beam. 4812 1620 24 28 3236 40 4448 52 0.20 0.25 0.30 0.35 0.40 0.45 0.50 0.55 0.60 0.65 Span-middle flexibility / mm Element numbers using element in Fig.1 using subsection uniform element Figure 1 12345678910111213141516 0.14 0.15 0.16 0.17 0.18 0.19 0.20 0.21 0.22 0.23 0.24 Cantilever end flexibility /mm Element numbers using the element in Fig.1 using the subsection uniform element Figure 1 Figure 8. Relationship between mid-point displacements and element numbers for the parabolic simple supported beam. Figure 5. Relationship between end-point displacements and element numbers for the tapered cantilever beam.  J. P. PU ET AL. 374 By applying the present element to analyze the non- uniform rectangular beams with both linear and parabolic variable heights, the results are being approached the accurate solutions much more. A non- uniform cantilever beam element and a non-uniform simple supported beam are presented to validate the element’s reliability, and the calculating results shows that, if using the subsection uniform finite elements one needs to divide more ele- ments to converge the numerical solution to the current exact solution. Therefore, by applying the present ele- ment to analysis the non-uniform beam, the analysis can be simplified distinctly and the computational results will approach the accurate solutions. 5.2. A Three-Span Continuous Haunched Bridge under a Moving Load In this example a three-span non-uniform continuous bridge is performed, the height of the beam is changeable in the plane (see Figure 9). A single load value of Pv= 100 kN, moving at a speed of v = 17 m/s, is considered. Total length of the bridge is L = 60 m, Young’s modulus is E = 3 × 1010 N/m2 and the mass density is ρ = 2400 kg/m3. The acceleration of the gravity is g = 9.81m/s2 in all ex- amples. The damping coefficient is ζ1 = ζ2 = 0.005 and the associated natural frequencies are ω1 and ω2, which were obtained in the main dynamic program. First, a case of which the haunched bridge with damp- ing subjected to a moving load, is considered. In this case the natural frequencies are not time-variant, because in this example the effects of inertial force, Coriolis force and centrifugal force induced by the moving mass have been ignored, so the mass, stiffness and damping matri- ces of the entire vibrating system are not time-variant yet. The finite element model of the bridge is composed of 36 uniform beam elements and 24 tapered beam elements. The numerical results for the deflections at each mid- span position are in excellent agreement with those available ones from the reference literature [6,8]. Next considering the bridge with damping subjected to a moving mass, since the effect of the inertial force, Coriolis force and centrifugal force induced by the mov- ing mass is existent, the overall matrices(include mass, stiffness and damping) and the associated natural fre- quencies are all time-variant at each computing time 1.0-1.6 m 1.0 m 1.6 m 0.5 m A A v P= 100 kN 12 m 6 m 6 m12 m 6 m 6 m 12 m Span-1 Span-3 Figure 9. A three-span continuous haunched bridge under a moving load. step. The numerical results for the deflections at each mid-span position of the bridge are shown in Figure 10. From Figure 10 it is shown that the difference of the displacements, for the case with moving load and with moving mass, is no evident. Since the deflections of the bridge are small, the effects of inertial force, Coriolis force and centrifugal force induced by the moving mass are also small to the dynamical responses of the bridge. Nevertheless, the last effect may be significant for other cases. 5.3. A Simple Supported Beam under a Moving Mass with Uniform Variable Speeds Considering a simple supported beam under a moving mass with uniform variable speeds (see Figure 11), the length of the beam is L = 100 m, Young’s modulus is E = 2.15 × 1011 Pa, the mass density of the beam is ρ = 6375 kg/m3 and the section area is A = 2.4 m2, the moment of inertia is I = 0.8 m4, the moving mass mv = 61.2 × 103 kg. We divided the beam into 50 beam elements, and taken the time step as Δt = 0.02 s, the initial velocity of the moving mass is v = 20 m/s, and the acceleration are a = 0, ±3, ±6 and ±9 m/s2, respectively. The dynamical displacement results of the mid-point of the beam have been computed by adopting the Newmark method. Under the conditions of being different accelerations (acceler- ating and decelerating), the dynamical displacement 0.0 0.10.2 0.3 0.4 0.50.60.70.80.91.0 -0.004 -0.002 0.000 0.002 0.004 0.006 0.008 0.010 Displacement / m x / L ML(S-2) MM(S-2) ML(S-1) MM(S-1) ML(S-3) MM(S-3) ML-moving load; MM-moving mass; S-span Figure 10. Deflections at each mid-point position for each span under a moving load/mass. 10 0 m vt x m v EI, ρA y v, a Figure 11. Simple supported beam under a moving mass with uniform variable speeds. Copyright © 2010 SciRes. ENG  J. P. PU ET AL.375 response contrast curves of the midpoint of the beam are given in Figures 12 and 13, respectively. From Figures 12 and 13 it is shown that, under the conditions of being same initial velocity, the dynamical displacements of the midpoint of the beam induced by moving mass with acceleration is bigger than that of with uniform velocity, and the larger the acceleration, the bigger the midpoint displacements of the beam. Whereas the dynamical displacements of the midpoint of the beam induced by moving mass with deceleration is smaller than that of with uniform velocity, and the larger the ac- celeration, the smaller the midpoint displacements of the beam. It is just opposite to the state with accelerated mo- tion. It is because the moving mass was exerted by a fric- tion induced between the contact interfaces. When the moving mass motion with acceleration, it is given a friction, which is in line with the movement di- rection, by the beam. At the same time, the beam is sub- jected to a reaction force imposed by the moving mass. This force can be regarded as an axial pressure acting on the beam. This pressure will generate an additional bending moment in the beam, so that the deflection of the beam will be increased. On the contrary, when the 01234 0.00 0.02 0.04 0.06 0.08 0.10 Displacement / m T / s a=0 m a=3 m a=6 m a=9 m Figure 12. Mid-point displacement of the beam with effect of acceleration. 01234 0.00 0.02 0.04 0.06 0.08 0.10 a= 0 m a=-3 m a=-6 m a=-9 m Displacement / m T / s Figure 13. Mid-point displacement of the beam with effect of deceleration. moving mass deceleration movement, the beam will be subjected to an axial tension, and this tension will gener- ate an additional bending moment within the beam to reduce the deflection. 5.4. A Three-Span Continuous Box Girder Bridge with Non-Uniform Section under a Moving Vehicle with Friction The purpose of this example is to compute a three-span continuous box girder bridge with non-uniform sections under a moving vehicle with friction, the bridge is com- posed of 7 box girder segments, the height of the box- section is changeable with both linear and parabolic soffit shape in the plane (see Figure 14). The total length of the bridge is L = 120m, the mass density is ρ = 2400 kg/m3 and Young’s modulus is E = 3 × 1010 N/m2. The acceleration of the gravity is g = 9.81m/s2, the moment of inertia I(x) is changeable with the position x. There is a vehicle at left end of the bridge, the weight of the vehi- cle is P = 20.6 × 104 N (while the front-wheel and rear wheel are P 1 = 8.0 × 103 N and P2 = 12.6 × 103 N, re- spectively), the space between the wheels is 2.0 m, at the time of t = 0 the front-wheel is just in the left end of bridge, the vehicle travels at a speed of v =15 m/s. When the vehicle moves forward 30 meters from the left end of the bridge at a uniform velocity, then it is bro- ken, so the velocity will be slowed down or stopped by contact friction. In order to impose the braking force, a ramp function is assumed (see Figure 15). This is based on the test results on highway vehicles conduced by the Transport and Road Research Laboratory [18]. The brak- ing force increases linearly to a maximum Fb max = εP and then stays constant until the vehicle either comes to a stop or crosses the bridge span and is written as P 1 v P 2 10 m20 m 20 m10 m 20 m 20 m 20 m 0.2 m 1 m 2 m 1 m-1.8 m 0.1 m 0.1 m 0.2 m Figure 14. A three-span continuous box girder bridge with variable sections. Copyright © 2010 SciRes. ENG  J. P. PU ET AL. 376 max 1 max 1 (), (1 )() , n bn nn b bn tt Ft tt F FT tT tt (39) where ε is the impact coefficient, P is the vehicle static weight, tn is the moment of begin braking and T is the moment of the braking force increases to the maximum value of Fbmax in time interval tn ≤ t ≤ tn+1. For this example, 60 linear and parabolic beam ele- ments are divided in overall bridge, the time step is Δt = 0.02 s. We take the friction coefficients as μ = 0.1, 0.2, 0.3 and 0.4, respectively. Taking the impact coefficient ε = 0.2, the numerical results for the midpoint deflections at mid-span position of the bridge are shown in Figure 16. Figure 16 shows that the dynamical displacements were affected by friction together with the impact coeffi- cient. The larger the friction coefficient, the larger the maximum dynamical displacements. The larger the fric- tion, the shorter the time of braking vehicle. In the condi- tion of being same friction force. The larger the impact coefficient, the bigger the dynamical displacements of midpoint at the mid-span of bridge. It can be observed from Figure 17 in evidence. tt n n+ 1 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 ε (1-ε 4 )( t n+1 -t n ) t T / s Impact coefficients Figure 15. Relationship of braking time vs. impact coeffi- cient. 01234 567 8910 -0.002 0.000 0.002 0.004 0.006 0.008 0.010 Displacement / m T / s without friction =0.1 =0.2 =0.3 =0.4 μ = 0.1 μ = 0.2 μ = 0.3 μ = 0.4 Figure 16. Deflections of mid-point position at mid span (ε = 0.2). 012345678910 -0.002 0.000 0.002 0.004 0.006 0.008 0.010 Displacement / m T / s without friction =0 =0.1 =0.2 =0.3 ε = 0 ε = 0.2 ε = 0.3 ε = 0.4 Figure 17. Deflections of mid-point position at mid span (μ = 0.2). 5. Concluding Remarks Dynamical solutions of the multi-span non-uniform beam with a moving vehicle can not be obtained by the theoretical means, the mass of the vehicle can not just be regarded as a simple moving load, the effect of inertial force, Coriolis force and centrifugal force is needed to be considered in general. The use of box beam bridge with non-uniform cross section is fairly common in the engi- neering. Numerical analysis for dynamic response of this kind of beam is beneficial to understand the dynamic characteristics of the bridge, to provide the scientific basis for the safe use of the bridge, and provided with a certain practical significance and application values. Us- ing oblique-shaped and Hparabolic-shaped beam element with non-uniform cross section Hcan improve the accu- racy and efficiency in solving. To define the dynamic response effect of the bridge caused by vehicle moving with variable speed as well as the friction and braking impact force on the bridge deck needs to considered the relationships of various factors synthetically, and then to find a design scheme closer to engineering practice com- bined with the relevant scientific experiment. 6 . References [1] L. Fryba, “Vibration of Solids and Structures under Moving Loads,” Noordhoff International Publishing, Groningen, 1972. [2] L. Fryba, “Dynamic Behaviour of Bridges due to High- Speed Trains,” In: R. Delgado, R. Calcada and A. Cam- pos Eds., Workshop Bridges for High-Speed Railways, Faculty of Engineering, University of Porto, Porto, 2004, pp.137-158. [3] C. W. Cai, Y. K. Cheung and H. C. Chan, “Dynamic Responses of Infinite Continuous Beams Subjected to a Moving Force-An Exact Method,” Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 123, 1988, pp. 461-472. [4] J. S. Wu and C. W. Dai, “Dynamic Responses of Mul- Copyright © 2010 SciRes. ENG  J. P. PU ET AL. Copyright © 2010 SciRes. ENG 377 tispan Nonuniform Beam due to Moving Loads,” Journal of Structural Engineering, Vol. 113, 1987, pp. 458-474. [5] H. P. Lee, “Dynamic Responses of a Beam with Interme- diate Point Constraints Subject to a Moving Load,” Jour- nal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 171, 1994, pp. 361-368. [6] G. Michaltsos, D. Sophianopoulos and A. N. Kounadis, “The Effect of a Moving Mass and other Parameters on the Dynamic Response of a Simply Supported Beam,” Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 191, 1996, pp. 357-362. [7] K. Henchi, M. Fafard, G. Dhatt and M. Talbot, “Dynamic Behavior of Multi-Span Beams under Moving Loads,” Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 199, 1997, pp. 33-50. [8] H. C. Kwon, M. C. Kim and I. W. Lee, “Vibration Con- trol of Bridges under Moving Loads,” Computers & Structures, Vol. 66, 1998, pp. 473-480. [9] D. Y. Zheng, Y. K. Cheung, F. T. K. Au and Y. S. Cheng, “Vibration of Multi-Span Non-Uniform Beams under Moving Loads by Using Modified Beam Vibration Func- tions,” Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 212, 1998, pp. 455-467. [10] Y. A. Dugush, M. Eisenberger, “Vibrations of Non- Uniform Continuous Beams under Moving Loads,” Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 254, 2002, pp. 911-926. [11] A. Yavari, M. Nouri, M. Mofid, “Discrete Element Analysis of Dynamic Response of Timoshenko Beams under Moving Mass,” Advances in Engineering Software, Vol. 33, 2002, pp. 143-153. [12] A. E. Martinez-Castro, P. Museros and A. Castillo- Linares, “Semi-Analytic Solution in the Time Domain for Non-Uniform Multi-Span Bernoulli-Euler Beams Trav- ersed by Moving Loads,” Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 294, 2006, pp. 278-297. [13] J. J. Wu, “Dynamic Analysis of an Inclined Beam due to Moving Loads,” Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 288, 2005, pp. 107-131. [14] J. J. Wu, “Vibration Analyses of an Inclined Flate Sub- jected to Moving Loads,” Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 299, 2007, pp. 373-387. [15] E. Esmailzadeh and M. Ghorashi, “Vibration Analysis of Beams Traversed by Uniform Partially Distributed Mov- ing Massed,” Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 184, 1995, pp. 9-17. [16] U. Lee, “Separation between the Flexible Structure and the Moving Mass Sliding on it,” Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 209, 1998, pp. 867-877. [17] U. Lee, C. H. Pak and S. C. Hong, “Dynamics of Piping System with Internal Unsteady Flow,” Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 180, 1995, pp. 297-311. [18] S. S. Law and X. Q. Zhu, “Bridge Dynamic Responses due to Road Surface Roughness and Braking of Vehicle,” Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 282, 2005, pp. 805-830. |