Open Journal of Safety Science and Technology, 2012, 2, 32-39 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojsst.2012.21005 Published Online March 2012 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ojsst) Safety in Chinese Medicine Research King-Fai Cheng, Ping-Chung Leung* Institute of Chinese Medicine, Prince of Wales Hospital, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China Email: *pingcleung@cuhk.edu.hk Received November 14, 2011; revised December 8, 2011; accepted December 22, 2011 ABSTRACT Safety of drugs is a common concern, regardless of traditional Chinese medicine or Western medicine. Historical ex- periences tell us that ignored drug safety evaluation would lead to serious consequences. Although Chinese medicine has been used for thousands of years, re-evaluation of the safety is still very important. The criteria for safety of Chi- nese herbal medicines should be the same as those for chemical drugs. Many Chinese herbal medicines have a long his- tory of traditional use. However, many of them do not possess proven safety and efficacy by today’s standards. Well- designed randomized controlled trials and comprehensiv e pre-clinical toxicological stud ies were not done. Although the lack of such evidence does not absolutely count against the efficacy and safety of Chinese herbs, laboratory and clinical investigation s are still needed before th e herbs cou ld be considered safe. This paper reviews the evaluation on the safety of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Keywords: Traditional Chinese Med icine; Safety Evaluation; Toxic Chinese Herbs; Adverse Reactions 1. Introduction The Need for Safety Evaluation In the last century, more than 40 major drug disasters happened in the world. Such incidents alerted people of all levels about the importance of drug safety. For exam- ple, the “thalidomide” event that occurred in the 1960s of the last century might be the most tragic and dramatic drug disaster. Thalidomide was used to treat ailments of pregnant women. Teratogenicity of thalidomide was not consider ed important. Th e result was 8000 to 10,000 bab ies were born with congenital malformations [1-3]. Such d isas- ters caused by chemical drugs made clinicians and authori- ties realize the importance of drug safety before promo- tion. In the situations of traditional Chinese medicine, although the history has been over 3000 years, and has been generally considered safe; the safety data derived from scientific tests remain very limited. We do not have es- sential data of many commonly used traditional Chinese medications such as maximum safe dose and duration of treatment that is considered safe. In actual fact, many commonly used Chinese herbs are already known to be high ly toxic, such as Strychnos, Radix Aconiti, Radix Aconiti Kusnezoffii, Fructus Crotonis, Sheeploitered Azalea etc. Others such as Rhizoma Ari- saematis, Rhizo ma Pinelliae, Realgar, Rhizo ma Polygoni Cuspidati, and Radix Sophorae Tonkinensis are moder- ately toxic; while many others are mildly toxic. Tradi- tionally, the principles of prescription in Chinese medi- cine include the theories of “nineteen avoidances (十九 畏)” and “eighteen clashes (十八反)” which lay down the recommendations on the avoidance of certain herbs with regard to either solitary use or in combination. Al- though the toxicity effects of medicinal herbs could be infrequen t, s low, and mo d er ate, wh en co mp ar ed with ch e mi- cal drugs, however herbal toxicity could also be more complex, and more obscure. The compositions of Traditional Chinese medicine are derived not only from plants, but also consist of minerals, and animal products. The degree of toxicity of toxic herbs may be affected by the soil, water, and breeding condi- tions. All of which are vulnerable to different forms of pollutions like pesticides, fertilizers and other toxic sub- stances. The more over authentications of the herbs could be defective and counterfeit herbs mixed with genuine supplies are not uncommon, thus giving more threat to safety. Processing of medicinal herbs, their storage, and transports, further complicated the safety issue. With regard to proprietary herbal medicinal products, the situation is more complicated. There could be adulterations of chemi- cals or pharmaceuticals, incompatible combination s, and/ or dangerous dosages. On the whole, due to the limited in- formation available, misunderstanding and negligence tend to be common. Therefore, when using Chinese medicine, we cannot rely only on traditional beliefs from either classi- cal documents or experience. A comprehensive evaluation on the safety of the medicine we intend to use is manda- tory on both clinical and research levels. *Corresponding author. C opyright © 2012 SciRes. OJSST  K.-F. CHENG ET AL. 33 2. Current Status of Safety Evaluation in Chinese Medicine Research 2.1. Toxicity Studies Basing on the Traditional Herbal Classification As the chemical compositions of medicinal herbs are ex- tremely complex, the study on their toxicology is difficult. The traditional principles of “nineteen avoidances” and “eighteen clashes” could be helpful but are obviously insufficient. There have been no systematic studies on the safety and compatibility of the pairs of herbs referred within the framework of the principles. The Traditional classification of “toxic Chinese herbs” was mostly based on the ancient clinicians’ experiences and records. “Shen Nong Ben Cao Jing” <神農本草經> divided traditional Chinese herbs into toxic and non-toxic types, without reference to their degree of toxicity. “Compendium of Materia Medica” <本草綱目> classi- fied the toxic herbs into four grades i.e. extremely toxic, highly toxic, moderately toxic, and sligh tly toxic without providing useful objective data to support the classifica- tion. Today, the pharmaceutical classification of toxicity is based on experimental data using animals which are fed with the drug until poisoning or death. Toxicity is therefore described quantitatively as the median lethal dose (LD50). When the oral lethal dose is less than 5 g/kg, the drug is classified as extremely toxic; the lethal doses between 5 - 15 g/kg and 16 - 50 g/kg are classified as moderately and slightly toxic. Non toxic drug refers to those producing mortality with doses of over 50 g/kg (Table 1) [4]. The modern pharmacological concepts of toxicity also include acute toxicity, subacute and chronic toxicity, special toxicity (mutagenicity, teratogenicity, carcinogenicity, abortion, and addiction toxicity etc). None of these modern methods of safety evaluation has been systematically applied in the evaluation of tradi- tional Chinese medicine. The defective guarantee on safety has certainly hindered the globalization of tradi- tional Chinese medicine. Table 1. Toxic classification of Chinese medicine. Item Highly toxic Moderately toxic Slightly toxic Symptom Very severe Severe Common side effect Organs damage d Key organs Key organs Rare organ damage High dose Death Death Rare death LD50 (oral) <5 g/kg 5 - 15 g/kg 16 - 50 g/kg Treat dose and toxic dose Very close Close Not close Toxic dose for adult <3 g 3 - 12 g 13 - 20 g Poisoning incubation <10 min 10 - 30 min >30 min or accumulation Our literature reviews indicated that scholars in the Chinese medicine field have actually done much work on the toxicity of traditional medicinal herbs. Interesting areas include: 1) The study of “eighteen clashes”—the reasons be- hind incompatible herbs: e.g. toxicity increases when Euphorbia kansui is used with Radix Glycyrrhiza; Adix aconiti lateralis p reparata with Rhizoma Bletillae; Vera- trum nigrum L. with Schizophyllumcommuneh or White Paeony Root [5]. Efficacy might also be affected because of incompatibility. Modern laboratory studies have shown that Yougui drink with ginseng lengthened th e swimming time of mice. However, if Veratrum nigrum L. is added, the effects on swimming rat became worse compared even without ginseng [6]. 2) Researches on medicinal herbs con taining aristolochic acid were plentiful because of many reports of serious toxicity [7-9]. 3) Other areas of extensive research work include: Berberine-induced neonatal jaundice [10], Cinnabar and arsenic contained herbs [11,12] and heavy metals related to medicinal herbs [13,14]. 2.2. Herb-Drug Interactions TCM medications could affect the metabolism of chemi- cal drugs which are being taken while their toxicities might also be significantly altered by the chemical drugs [15-18]. Synergistic or additive therapeutic effects may lead to unfavorable adverse events related to over-dosage. On the other hand antagonistic interactions could result in defi- cient efficacy and therapeutic failure. The potential inter- action of herbal medicines with chemical drugs is a major safety concern, which must not be underestimated because the use of herbal medicines is gaining populari ty. A distinguished herbal expert of the Yuan Dynasty (about 1300 AD) Zhang Zhi-he wrote in his collection of clinical cases (儒門事親) [19]. “Toxicity is a property of all drugs not just that poisons are toxic. One must not forget that herbs as popular as Liquorice (Radix Glycyr- rhizae) and Radix Sophorae Flavescentis could also be toxic. Undesirable outcomes follow over dosages.” Cura- tive and toxic potentials are properties of all drugs. The key to successful treatment is to select the righ t drug, the right dosage and the right channel of administration. The simultaneous administration of Chinese medicine and pharmaceuticals must be arranged with care. It has alread y been reported that when herbal medicine is used together with insulin injection or oral anti-diabetics for diabetic control, hypoglycemia frequently result [20]. The interactions between Chinese herbs and modern drugs should be common issues, yet reports are fewer. Likewise medicinal herbs are getting popular in the US, yet toxicities and interactions related are not thoroughly Copyright © 2012 SciRes. OJSST  K.-F. CHENG ET AL. 34 known. According to a survey in the US on 1000 patien ts attending the accident and emergency departments, 538 of them were using over 1087 types of various forms of drugs, and 30 of them have already shown unfavorable side-effects [21]. Drug interactions could be investigated by in vitro and in vivo experiments, but the results obtained could be inconsistent. For example, St. John’s wort, an herb com- monly used in America was shown to suppress monoam- ine oxides in vitro, but such observations could not be demonstrated in vivo studies. When used appropriately herbal medicine used together with modern medicine may produce better outcomes. For example, in the case of sore throat and tonsillitis, co- administration of Radi x Isatidis (板蘭根) with Trimethoprin has been found to significantly strengthen the immune system, w hich m ight b e respo nsibl e for t he bett er outc ome. On the contrary, disastrous outcomes may follow the inappropriate use of Chinese medicine together with modern medicine. For example, co-administration of digoxin and Liu Shen Pill (六神丸) had led to repeated ventricular extrasystoles; and mixing Cinnabaris (硃砂) containing Chinese Medicine with halogen compounds could pro- duce disastrous toxic outcome [22]. Some herbal medicine, apparently safe, could become toxic with overdose. Aloe vera is a good example. In high doses, Aloe vera led to hypersensitive reactions of erythema, urticaria, even nausea and diarrhoea in chil- dren; uterine bleeding in pregnant women, and bleeding among t hose s ufferi ng fr om ha emorr hoids or epi staxi s [23] . 3. Study of Safety Dosages of Chinese Medicinal Herbs Each drug should have its unique proper dose range. How- ever, for Chinese medicinal herbs unlike chemical drugs, they have not been pharmaceutically tested to define its effective dose, maximal dose and toxic dose. Only clas- sic clinical experiences are available. Obviously, unduly increased doses or long administrations could induce adverse reactions. Even herbs believed to be “mild” such as licorice could induce toxic effects if improperly used [24]. For any drug, its toxicity is closely related to its do s age, and when excessive dose is given, even non-toxic drug should produce adverse effects. Cancer drugs are well known toxic agents and yet could be used cleverly for cancer treatment [25]. A Chinese herb Guanmutong, is usually administered in dose of 3 - 6 grams. However it readily produces acute renal failure and anaphylactoid purpura while higher doses are used [26]. Tripterygium wilfordii and its preparations are commonly used in China for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. However since its therapeutic do se is very close to its toxic dose, it may lead to gastrointestinal bleeding, even visceral necrosis and renal failure [27,28]. Overdose of another medicinal herb, viz. Vietnamese Sophora Root could cause cardiac failure, shock and even death [29,30]. In addition, Pro- prietor Chinese medicine has also been reported for severe adverse events. For example, cinnabar sedative pills and Tianwangbuxin Dan (both preparations containing cin- nabar) when used together, have been reported to be dangerous [31]. The safety duration of administration of Chinese medi- cine is another current problem in Chinese medicine re- search. As the desirable efficacy of Chinese medicine is expected to be slow, the duration of administration can- not be shor t. Hence, the long duration wo uld invite more adverse effects. It is therefore essential to test out the opti- mal doses and duration of administration in the event of maintaining both effectiveness and safety. 4. Toxicological Studies Toxicology of Chinese medicine includes experimental toxicology, clinical to xicology and tox icokinetics. Toxic- ity and adverse reactions of traditiona l Chinese medicine in the clinical application have attracted general concern but remain insufficient. The misconception that traditional Chinese medicines are “natural drugs” without toxic effects is still widely believed. In fact, some Chinese herbal medicines are not only toxic, but also carcino genic. The Virus Section of the China Institute of Medical Science on Prevention has studied 1693 kinds of Chinese herbs and plants, and found that 52 are carcinogenic [32]. According to a report of the Monitoring Center for Adverse Drug Reactions of the Ministry of Health in China, about 20 million people in China died of adverse drug reactions and d rug-induced diseases every year [33]. According to a survey in China on the analysis of 382 adverse drug reaction cases in China in 2006, the propor- tion of adverse reactions induced by Traditional Chinese Medicine was as high as 25.1%, only second to that of induced by antibiotics [34 ]. Since the chemical composi- tion of chemical medicine is clear, and the research be- fore marketing is well regulated, the mechanisms of ad- verse reactions are known. On the other hand, the researches of adverse effects and toxic itie s of trad ition al Ch in es e medi- cine are not well developed, for example, the study of clinical pharmacology, toxicology and drug metabolism of traditional Chinese medicine are started late and de- veloped slowly, many people are lack of knowledge of side effects or adverse effects of traditional Chinese medi- cine. In fact, the adverse effects of traditional Chinese medicine are not uncommon. About 90% traditional Chinese medicine their toxico- logical data are still unknown, such as their classification, the toxic ingredients, the tox ic reactions, their prevention, treatment and rescue etc. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. OJSST  K.-F. CHENG ET AL. 35 4.1. Systematic Study and Safety Evaluation Investigators reviewed the reports of toxic and adverse reactions related to TCM from 110 medical journals from 1915 to 1994. They found that there were totally 6061 cases of adverse reactions reported. Before 1950 s only 26 adverse reactions were reported. The number increased in 1960s to 147 reported in 1970s to 398, and in 1980s to 2217. From the four years of 1991 to 1994 there were already 3273 cases, which sharp rising trend is therefore obvious [35]. Liver and kidney toxicities are related to Chinese medicinal herbs, and systematic studies and safety evaluation, should accordingly set the priorities. 4.2. Pre-Clinical Safety Evaluation Pre-clinical safety evaluation is intended to provide the scientific evidences to predict the toxicity of a new drug through toxicology tests before it is clinically used. The toxipathological examination is to determine the patholo- gical damages in site, extent, nature, including the long- term effects. Most experiments are conducted through animal tests, which include acute toxicity, long-term toxicity, teratogenicity, and carcinogenicity tests etc (Table 2), all of these tests are inseparable from toxicpathology. The longer the testing period, the more important the toxi- pathological examination. Therefore, the toxipathology is the most important component of preclinical safety eva- luation. 4.2.1. Acute Toxicity Stu dy The objective of acute toxicity study is to assess the acute toxicity of a test item when administered as a single dose followed by an observation period of 14 days and thereby obtain information both about hazard assessment and for ranking articles [36]. For chemical drugs, the toxicity can be classified into 6 levels (Table 3). Table 2. Content of preclinical safety evaluation of traditional Chinese medicine. Acute toxicity test (oral) Long-term toxicity test (oral) Acute toxicity test (skin) Long-term toxicity test (s kin) Skin/Mucosal irritation test Skin sensitization test Genetic toxicity tests Reproductive toxicity test Carcinogenicity test Drug dependence test However, for most herbal medicines, the value of median lethal dose (LD50) is not obtainable with practical measures because of the limits on concentration or volume of the medicine, the acute toxicity can be represented by its maximum tolerable dose (MTD). 4.2.2. Repeated Dose Toxicity Study Acute toxicity test does not fully reflect the safety of Chinese medicine. As traditional Chinese medicine usually requires long periods of administration, a long-term toxicity test could better reflect the safety. The study provided information on the major toxic effects, indicated target organs and the possibility of accumulation, and would provide an estimate of adverse-effects related to certain dose levels which could be used for chronic studies and for establishing safety criteria for human exposure [36]. Long-term toxicity test is one of the key components of the pre-clinical safety evaluation, and it is the fun- damental basis for the approval of the new drug for cli- nical trial. The purposes of the repeated dose toxicity tests in- clude: 1) To determine whether the test article is suitable for clinical trial; 2) To predict the po ssible toxicity and the safety range for the human clinical applicatio n; 3) To provide an importan t reference of th e initial d ose selected for clinical trial; 4) To determine the key observations and reveal pre- ventive measures in clinical trials. In short, the data of long-term toxicity test supply evidences to determine whether a drug could be further developed. The duration of long-term toxicology studies would depend on the nature of the herbal preparation and the actual time of clinical trial application. In general, if the herbal medicine is indicated for single dose administra- tion or for repetitive administrations spanning less th an a week, the administration period of long-term test should be 2 weeks to a month; if the herbal medicine is for re- Table 3. Classification of chemical toxicity (oral) from GB 15193.3-94. Category LD50 (mg/Kg) Extremely toxic 1.0 or less Highly toxic 1.0 - 50.0 Moderately toxic 51.0 - 500.0 Slightly toxic 501.0 - 5000.0 Practically non-toxic 5001.0 - 15,000.0 Non-toxic >15,000 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. OJSST  K.-F. CHENG ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. OJSST 36 petitive administration spannin g over a week, the test ad- ministration term should be 3 - 4 times the period of clinical treatment (the maximal period is 6 months for rodents, 9 months for non-rodents) (Table 4) [36]. Animal species: The test animals include at least two species (includ i ng both rodent and non-rodent). Rodent: White rats are the most commonly used animals. Non-rodent: Dogs and monkeys are most commonly used animals. Dose Levels: 3 different dose levels and 1 control group. Observation: General observation: physical signs, weights, appearance. Hematology: blood test. Blood chemistry: livers, kidneys. Pathology: pathological di agnosis. There was research reported that some herbs could in- duce pathological damages if repeated doses were given (Table 5) [37]. Special toxicity studies include: Mutagenicity Test; Teratogenicity Test; Carcinogenicity Test. Table 4. Clinical treatment course and experimental administration period. Clinical treatment course Experimental administration Single dose or less than 1 week 2 weeks to a month over a week 3 - 4 times of the period of clinical tr eat ment (Not over 6 months in maximum for rodents, Not over 9 months for non-rodents) Table 5. 44 herbs that induce pathological damages through long-term toxicity test. Superficies-resolving h e rbs (解表藥) 桑葉 (Folium mori) Heat-clearing herbs (清熱藥) 天花粉 (Radix Trichosanthis), 青黛 (Indigo Naturalis), 青蒿 (Artemisia annua L.), 蒲公英 (Herba Taraxaci), 千里光 (Herba Senecionis Scandentis), 半邊蓮 (Lobelia chinensis), 虎杖 (Rhizoma Polygoni Cuspidati), 野菊花 (Chrysanthemum Indici Flos) Expelling phlegm herbs (化痰止咳藥) 半夏 (Pinellia Tuber), 馬兜鈴 (Aristolochia debilis), 啤酒花 (Humulus lupulus) Herbs for purgation (瀉下藥) 大黃 (Rheum palmatum L.), 蓖麻子 (Semen ricini) Herbs for eliminating dampness and diuresis (滲濕利水藥) 澤瀉 (Rhizoma Alismatis), 木通 (Akebia Stem) Herbs for dispelling pathogenic wind and removing dampness (祛風濕藥) 獨活 (Radix Angelicae Biseratae), 秦艽 (Radix gentianae macrophyllae), 蒼耳子 (Fructus Xanthii), 八角楓 (Alangium chinense), 松蘿 (Chinese Usnea), 雷公藤 (Common Threewingnut Root) Herbs for promoting b lood circulation and removing blood stasis (活血化瘀藥) 莪術 (Rhizoma Curcumae Aeruginosae), 延胡索 (Rhizoma corydalis) Supplementing and boosting her bs (補益藥) 甘草 (Radix Glycyrrhiza), 補骨脂 (Psoralea corylifolia L.), 白術 (Rhizoma Atractylodis Macrocephalae) Anti-helminthic herbs (驅蟲藥) 苦楝皮 (Cortex meliae), 常山 (Antifeverile Dichroa Root) Anti-cancer herbs (抗腫瘤藥) 長春花 (Herba Catharanthi rosei), 喜樹 (Camptotheca acuminata), 野百合 (Crotalaria sessiliflora L.), 大豬屎豆 (C rot ala ria assa mic a), 龍葵 (Solanum nigrum L.), 三尖杉 (Cephalotaxus fortunei Hook. f.), 斑蝥 (Spanish fly), 山慈菇 (Pleione bulboc odioides) Others (其他) 甜瓜蒂 (Cucumis melo L), 蟾酥 (Venenum bufonis), 棉籽 (Cottonseed), 鉤藤 (Gambir Plant), 銀杏 (Ginkgo biloba), 博落回 (Macle a ya corda ta), 馬桑 (Coriaria sinica Maxim)  K.-F. CHENG ET AL. 37 4.2.3. Reproductive Toxicity Study The objective is to examine whether the test medicine has toxic effects on animal’s reproductivity and whether it has teratogenic effects on their offspring. The herbal drugs intended for contraceptives, preventing miscarriage, prolactin, pregnancy-related drugs, and those affecting fetal development, the reproductive toxicity testing is required. Local toxicity stud y: The objective of local toxicity test is to examine whe- ther local-applied medicines will cause any irritation or allergic reaction, which includes: Skin irritation; Skin sensitization; Eye irritation. 4.2.4. Drug De pendence Test When the medication is used for analgesic and sedative- hypnotics, the drug dependency test is required . 4.3. Clinical Safety Evaluation Olsen conducted a review looking at the toxicity of pharmaceuticals observed in humans compared with those earlier observed in experimental animals. This survey in- cluded input from 12 pharmaceutical companies with data compiled from 150 compounds. A total of 221 human toxicity (HT) events were reported. The results showed a positive HT concordance rate of 71% for rodent and non-rodent species. For non-rodents alone the predictive rate was 63% of HTs and for rodents alone, it was 43%. The results also showed that 94% HT were first observed in studies of 1 month or less in duration [38]. Most human toxicity could be found in single dose toxicity test. On the whole, 25% of human toxicity are observed in safety and pharmacology experiments. Using animals China scholars observed embryonic toxicity in animal experiments using Artemisinin. However, in clinical studies pregnant women taking this drug have no t produced abnor mal babies [39]. In spite of the weak correlation, animal studies are still important. In vivo studies are more reliable than in vitro experiments. This is particularly important for tra- ditional Chinese medicine, because most Chinese herbal medicines are tested with their gross extracts, with unclear chemicals, impurities, and other variable physical factors might all affect the in vitro resu lts. Therefore, toxicology studies of Chinese medicine must be based on in vivo tests, rather than in vitro studies alone. Herbal poisoning must be differentiated from adverse reactions. Poisoning refers to tissue and organ damages caused by toxic chemicals in the medicinal herb. Adverse reaction is a response to the herbal item which is noxious and unexpected and which occurs at doses normally used in humans for prophylaxis, diagnosis, or therapy of dis- ease or for the modification of physiologic function. Ad- verse drug reactio n is harm directly caused by th e drug at normal doses, during normal use. When conducting a clinical trial of Chinese medicine, it is important not only to observe the clinical efficacy, but also to observe the clinical safety. Clinical safety evaluation of traditional Chi- nese medicine therefore includes toxicity of the drug, ad- verse reaction monitoring, and the interactions between traditional Chinese medicine and chemical medicine. 4.4. Adverse Reactions of Chinese Medicine and Post-Marketing Re-Evaluation Animal toxicology study has its limitations, but the clinical study alone is unable to find ou t all toxicities of the drug. As the number of subjects (sample size) for the clinical study of new drug is limited and the inclusion/exclusion criteria are stringent, some adverse reactions cannot be found during the clinical trial period. According to sta- tistical data, if the incidence of adverse reactions is less than ten thousandth, the adverse reactions cannot be found during pre-marketing clinical trials [40]. Therefore, the toxicology studies of Chinese medicine should be extended to post-marketing evaluation i.e. post-marketing adverse events monitoring . Adverse reactions for herbal administration might be due to the processing of the herbs duration of its admi- nistration, contaminations, individual differences, medi- cine incompatibility, etc. Most Chinese decoction or proprietary compound con- sist of a number of herbs, and each herb contains many chemical ingredients. Once adverse reaction occurred, it is most difficult to identify the causes; and the respon- sable chemical component. As pre-market clinical trials of Chinese medicine are usually conducted in specific population groups with spe- cial age ranges, unique health conditions and the obser- vational times are limited. Observations on adverse effects, mortalities and quality of life would not have universal value. This gives a post-market evaluation extra values. Toxicology study of the Chinese Medicine should also make use of new knowledge and new techniques of toxi- cology, which apply to chemical drug development for its healthy development. 5. Conclusion Chinese herbal medicine is the most important part of Traditional Chinese medicine; their safety issues directly affect the clinical efficacy and drug development, as well as its globalization. The reasons that induce adverse re- actions of traditional Chinese medicine are complex and divergent, and require systematic studies. Worries about TCM safety have come up many times because of senti- mental reports about mass toxicities. It is therefore timely Copyright © 2012 SciRes. OJSST  K.-F. CHENG ET AL. 38 to look for practical, systematic ways to ensure TCM safety through proper evaluations, and tests. 6. Acknowledgements The authors would like to acknowledge the Ming Lai Foundation and The International Association of Lions Clubs District 303-Hong Kong and Macau Tam Wah Ching Chinese Medicine Resource Centre for the support given to the Institute of Chinese Medicine, CUHK. REFERENCES [1] W. Lenz, “Thalidomide and Congenital Abnormalities,” The Lancet, Vol. 2, 1962, p. 45. [2] W. Lenz, “A Short History of Thalidomide Embryopathy,” Teratology, Vol. 38, No. 3, 1988, pp. 203-215. doi:10.1002/tera.1420380303 [3] B. J. Yuan and Z. Q. Wang, “The Purpose and the Sig- nificance of Preclinical Safety Evaluation,” Military Medical Science Press, Beijing, 1997. [4] L. Y. Xia, “Modern Toxicology of Chinese Medicine,” Tianjin Science and Technology Translation and Pub- lishing Corporation, Tianjin, 2005. [5] J. L. Li, “Animal Experimental Studies of ‘Eighteen Clashes’ of Chinese Medicinal Herbs,” Journal of Chang- chun College of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Vol. 2, No. 3, 1988, p. 89. [6] X. S. Gao, “Eighteen Clashes Research of Chinese Me- dicinal Herbs,” Chinese Ancient Books Publishing House, Beijing, 1991. [7] J. Lu, “Studies on the Aristolochic Acid Related Crude Traditional Chinese Medicine,” Drug Standards of China, Vol. 3, No. 2, 2002, pp. 49-50. [8] L. S. Wang, “Toxic Effects of Aristolochic Acid,” Tradi- tional Chinese Drug Research & Clinical Pharmacology, Vol. 12, No. 6, 2001, pp. 394-395. [9] G. Z. Jiang and L. Chen, “New Research Progress of Toxicity of Aristolochic Acid in Traditional Chinese Medi- cine,” Chinese Agricultural Science Bulletin, Vol. 24, No. 9, 2008, pp. 84-87. [10] N. K. Ho, “Traditional Chinese Medicine and Treatment of Neonatal Jaundice,” Singapore Medical Journal, Vol. 37, No. 6, 1996, pp. 645-651. [11] L. Zhang, S. H. Gao, C. F. Zhou, et al., “Safety Issues of Traditional Chinese Medical Preparations Containing Ar- senic Substances: Review Starting from Niuhuang Jiedu Pian (Wan),” China Journal of Chinese Materia Medica, Vol. 31, No. 23, 2006, pp. 2010-2012. [12] P. Li, “Research Status of Traditional Medicine Cinna- bar,” West China Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Vol. 25, No. 5, 2010, pp. 622-624. [13] K. Yang, X. F. Li, Q. H. Li and G. H. Ding, “Overview of Adverse Reactions of Chinese Medicine Containing Heavy Metals and Arsenic,” Chinese Journal of Hospital Phar- macy, Vol. 28, No. 4, 2008, pp. 301-304. [14] D. X. Wang and X. L. Zhu, “Poisoning of Traditional Chinese Mineral Medicines Containing Heavy Metal: Clinical Presentation and Management,” Adverse Drug Reactions Journal, Vol. 9, No. 1, 2007, pp. 43-45. [15] R. L. Page and J. D. Lawrence, “Potentiation of Warfarin by Dong Quai,” Pharmacotherapy, Vol. 19, No. 7, 1999, pp. 870-876. doi:10.1592/phco.19.10.870.31558 [16] B. Cheng, C. T. Hung and W. Chiu, “Herbal Medicine and Anaesthesia,” Hong Kong Medical Journal, Vol. 8, No. 2, 2002, pp. 123-130. [17] A. A. Izzo and E. Ernst, “Interactions between Herbal Medicines and Prescribed Drugs: A Systematic Review,” Drugs, Vol. 61, No. 15, 2001, pp. 2163-2175. doi:10.2165/00003495-200161150-00002 [18] A. Fugh-Berman, “Herb-Drug Interactions,” The Lancet, Vol. 355, No. 9198, 2000, pp. 134-138. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(99)06457-0 [19] Z. H. Zhang, “Ru Men Shi Qing,” The Yuan Dynasty, AD1300. [20] The American Society of Anesthesiologists, “Anesthesi- ologists Warn: If You’re Taking Herbal Products, Tell Your Doctor before Surgery,” 2001. http://anestit.unipa.it/mirror/asa2/PublicEducation/herbal. html [21] J. Doucet, P. Chassagne, C. Trivalle, I. Landrin, M. D. Panty, N. Kadri, J. F. Menard and E. Bercoff, “Drug-Drug Interactions Related to Hospital Administrations in Older Adults: A Prospective Study of 1000 Patients,” Journal of American Geriatric Society, Vol. 44, No. 8, 1996, pp. 944-948. [22] X. A. Zhang, “Drug Induced Diseases,” China Medical Technology Publishing House, Beijing, 1997. [23] D. M. Tan, “Abuse of Aloe Vera ,” Science Daily, Vol. 30, 2001. [24] J. M. Zhang, “Excessive Intake of Licorice can Cause Potassium Loss,” International Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Vol. 14, No. 6, 1992, p. 14. [25] J. Hu, Ji. Fang, Y. Dong, S. J. Chen and Z. Chen, “Arse- nic in Cancer Therapy,” Anticancer Drugs, Vol. 16, No. 2, 2005, pp. 119-127. doi:10.1097/00001813-200502000-00002 [26] Q. L. Li, “One Case of Allergic Purpura Caused by Ex- cessive Aristolochia Manshuriensis Decoction,” China Journal of Chinese Materia Medica, Vol. 25, No. 2, 2000, p. 124. [27] K. B. Bi and Y. L. Jia, “1 Case of Acute Renal Failure Induced by Overdose of Tripterygium Decoction,” China Journal of Chinese Materia Medica, Vol. 25, No. 3, 2000, p. 191. [28] Z. Y. Cau, “Clinical Analysis of 72 Cases of Acute Poi- soning after Oral Tripterygium,” Hunan Journal of Tradi- tional Chinese Medicine, Vol. 8, No. 2, 1981, p. 17-19. [29] J. Z. Wang, “3 Cases of Tonkinensis Poisoning Report,” Clinical Medicine, Vol. 8, No. 6, 1988, p. 279. [30] Y. M. Wen, “One Death Case of Poisoning after Oral Taking Radix Sophorae Tonkinensis,” Chinese Journal of Hospital Pharmacy, Vol. 11, No. 6, 1991, p. 271. [31] G. T. Zhang and A. Y. Zhao, “Improper Combination of Copyright © 2012 SciRes. OJSST  K.-F. CHENG ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. OJSST 39 Proprietary Chinese Medicine in Clinical Practice,” Chi- nese Journal of Hospital Pharmacy, Vol. 191, No. 10, 1999, p. 621. [32] “52 Kinds of Hospital Inhibited Plants Which Contain ‘Epsteln-Barr Virus Early Antigen-Inducer’ Have Cancer- promoting Effects,” Chinese Hospital Architecture & Equipment, Vol. 4, 2003, p. 11. [33] W. L. Xue, “From the Safety of Traditional Chinese Medicine to Its Internationalization,” Information on Traditional Chinese Medicine, Vol. 22, No. 2, 2005, pp. 6-7. [34] Y. P. Xiao, X. H. Ren and Y. X. Wu, “Lianyuan City Drug Adverse Reaction Analysis Report,” Journal of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, Vol. 6, No. 5, 2007, pp. 172-173. [35] S. T. Yuan, “Consideration on the Problem of Ascension of the Case Poisoned by Chinese Traditional Medicines,” China Journal of Chinese Materia Medica, Vol. 25, No. 1, 2000, p. 56. [36] Chinese Medicine Council of Hong Kong, “Registration of Proprietary Chinese Medicine (Application Hand- book),” 2004. http://www.cmchk.org.hk/pcm/pdf/reg_handbook_e.pdf [37] J. Ma, “The Relationship between Drug Toxicology and Other Disciplines,” Shanghai National Center for New Drug Safety Evaluation GLP Training Seminars, Cheng- du, 6 March 2011. [38] H. Olson, G. Betton, D. Robjnson, et al., “Concordance of the Toxicity of Pharmaceuticals in Humans and Ani- mals,” Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology, Vol. 32, No. 1, 2000, pp. 56-67. doi:10.1006/rtph.2000.1399 [39] L. X. Yang, “Toxicology Studies of Artemisinin and Its Derivatives,” Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Vol. 1, No. 1, 1982, pp. 3-6. [40] Center for Evaluation and Research, “Annual Report of 2001 to Nation,” 2001. http://www.fda.gov/eder/reports/rtn/2001

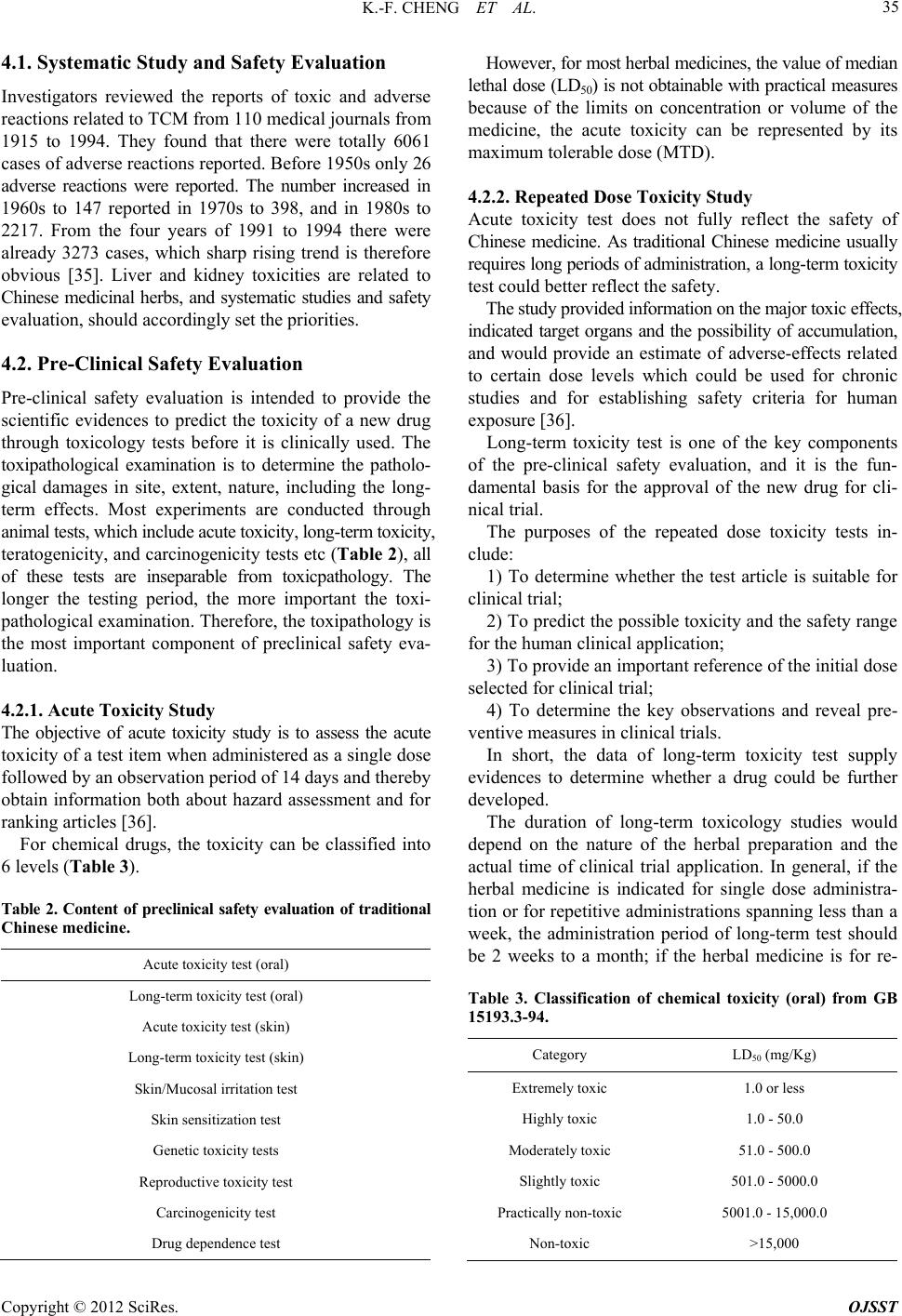

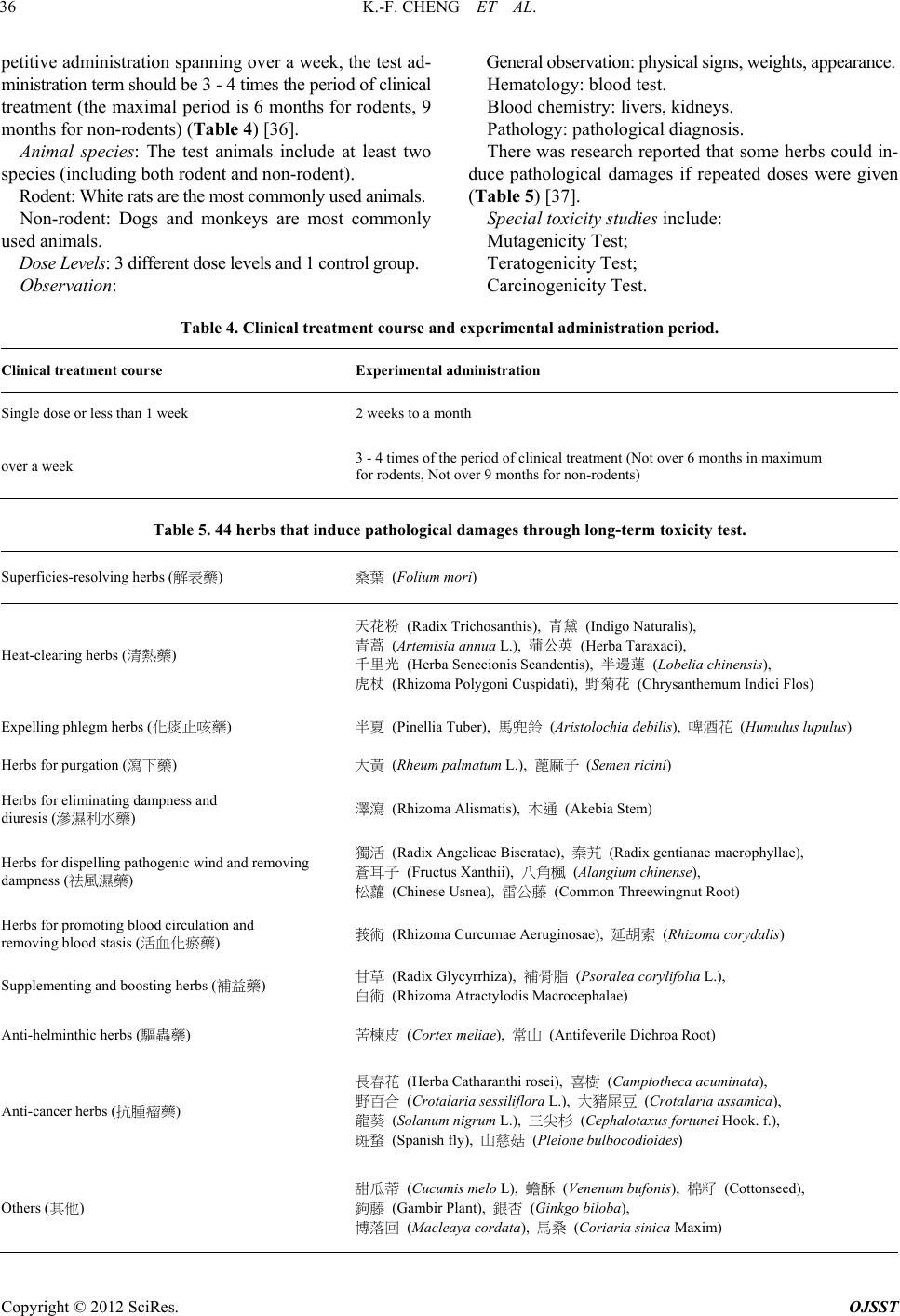

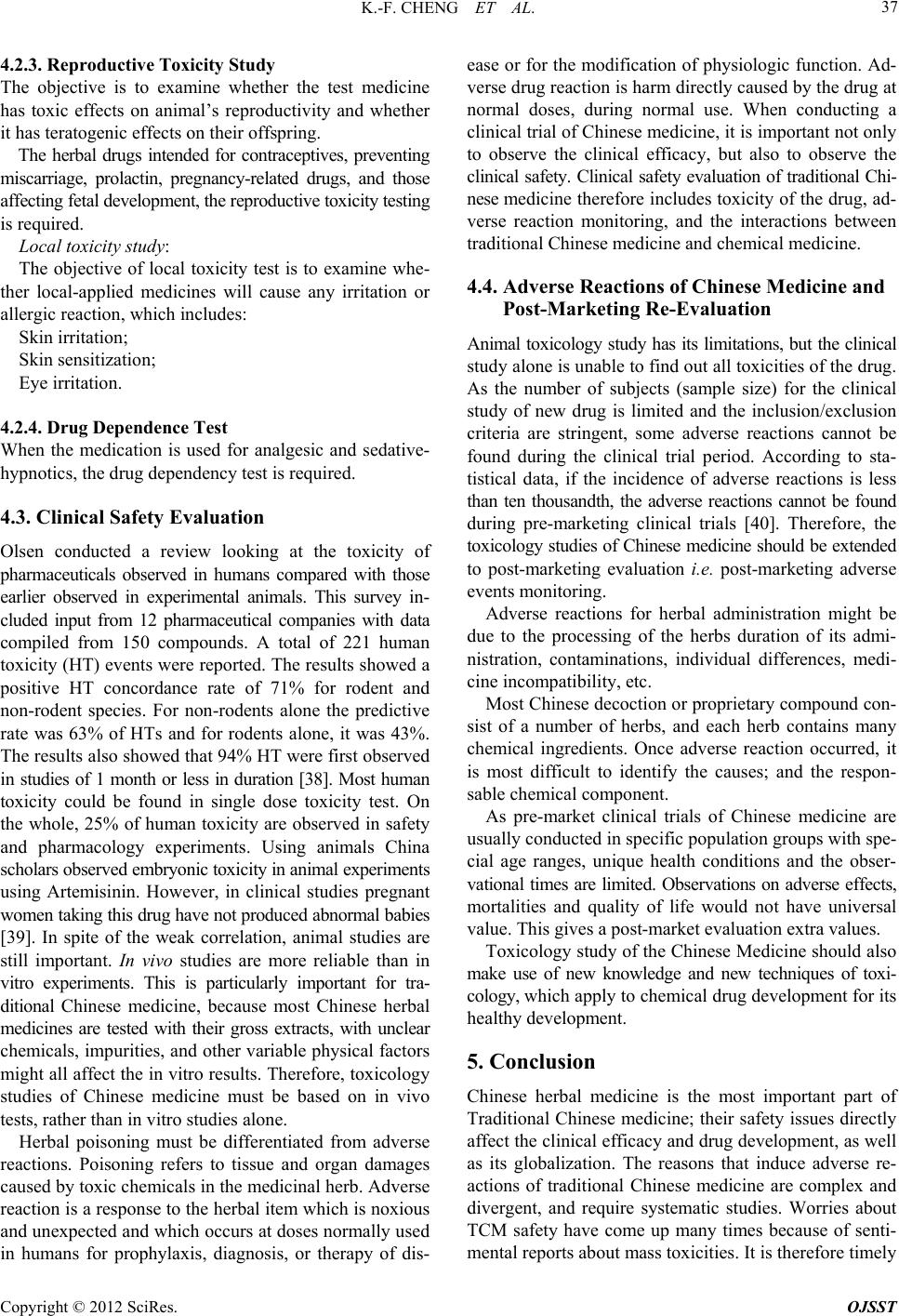

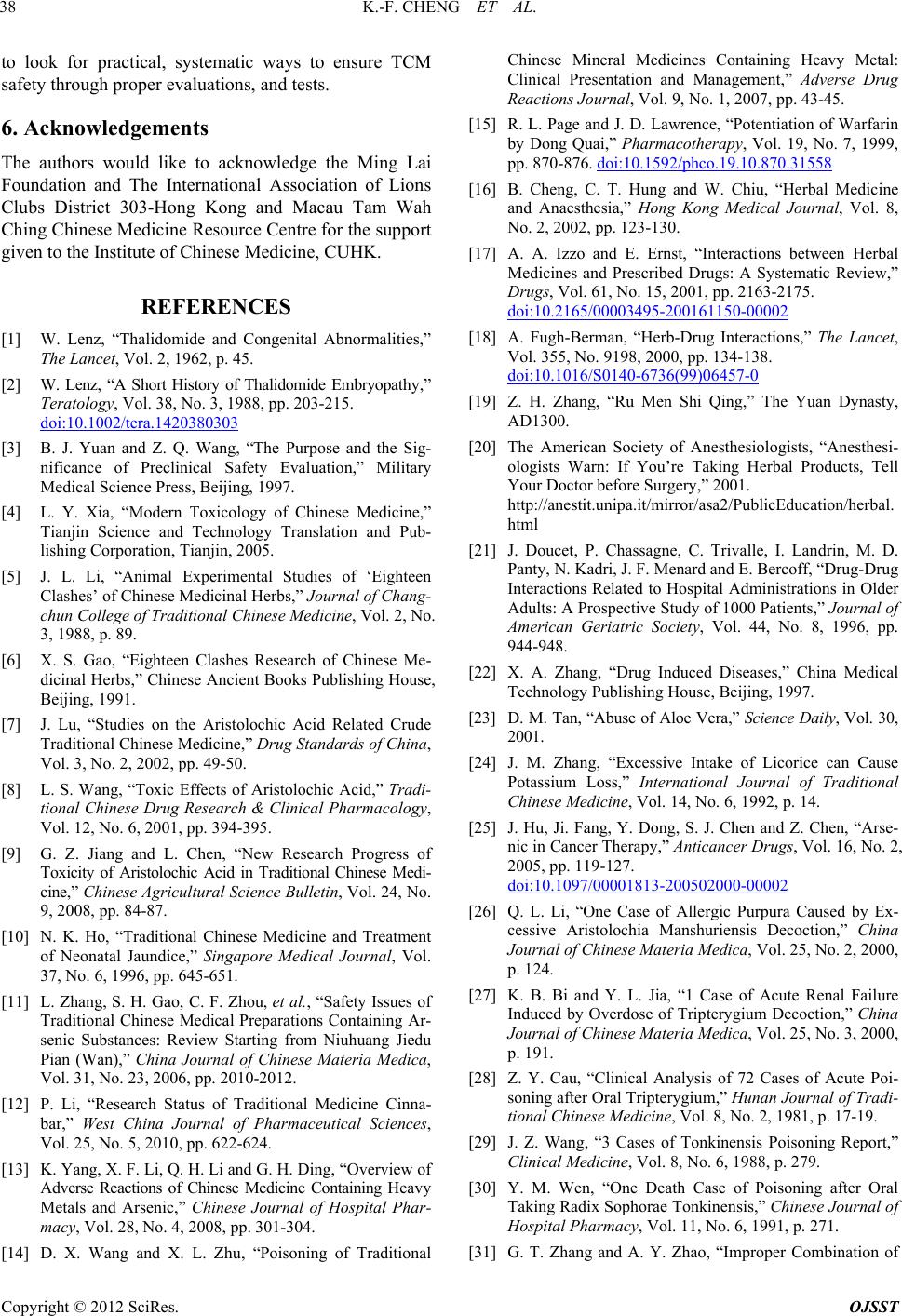

|