Psychology 2012. Vol.3, No.3, 231-236 Published Online March 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/psych) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/psych.2012.33032 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 231 Assessment of Alexithymia: Pychometric Properties of the Psychological Treatment Inventory-Alexithymia Scale (PTI-AS) Alessio Gori1,2*, Marco Giannini1, Giulia Palmieri3, Roberta Salvini4, David Schuldberg5 1Department of Psychology, University of Florence, Florence, Italy 2“Gruppo Incontro” Social Cooperative, Pistoia, Italy 3School of Comparative Psychotherapy, Florence, Italy 4Center for Employment and Guidance, Pisa, Italy 5Department of Psychology, The University of Montana, Missoula, USA Email: *alessio_gori@libero.it Received April 3rd, 2011; revised December 6th, 2011; accepted January 15th, 2012 Background: The aim of this study is to investigate the psychometric properties of a new measure of alexithymia, the Psychological Treatment Inventory-Alexithymia Scale (PTI-AS). Method: A group of 778 participants completed the PTI-AS. In order to evaluate aspects of concurrent validity, a part of the sample (n = 116) completed the PTI-AS, the Twenty-Items Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20) and the Bermond-Vorst Alexithymia Questionnaire (BVAQ). In order to evaluate aspects of discriminant validity a group of patients with a diagnosis of Eating Disorders completed the PTI-AS, the TAS-20 and the Eat- ing Disorders Inventory (EDI-3). Results: Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) showed a solid structure with one factor. Results were confirmed by Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA), which yielded good fit indices (CFI = .98; TLI = .95; RMSEA = .08; SRMR = .04). The PTI Alexithymia Scale showed a good degree of internal consistency (α = .88). Correlations between the PTI Alexithymia Scale, the TAS-20 (r = .74, p < .001) and the BVAQ (r = .40, p < .001) were statistically significant, supporting the scale’s concurrent validity. Conclusion: Thanks to its good psychometric properties the PTI-AS can be consid- ered as a brief and useful measure for assessing alexithymia. Keywords: Alexithymia; Personality Tests; Psychological Assessment; Psychometrics; Affective Symptoms Introduction The term alexithymia (derived from the Greek a = lack, lexis = word and thymos = mood) was introduced by Sifneos (1973) to indicate a cognitive-affective disturbance that affects the way individuals regulate their emotions. It is defined as a multidi- mensional construct that refers to personality traits relating to difficulty in identifying and expressing feelings and the inabi- lity to distinguish between emotions and bodily sensations. Furthermore, it is also characterized by a reduction or incapaci- ty to fantasize and to experience emotions (Nemiah & Sifneos, 1970; Taylor, Ryan, & Bagby, 1985). Alexithymia should be considered as a risk factor for those medical, psychiatric, or behavioral problems that are influenced by disordered affect regulation (Taylor, Bagby, & Parker, 1997). In fact, alexithymia is associated with a failure to use adaptive affect regulation processes and it is hypothesized to be one of several factors that contribute to various physical and mental health problems including undifferentiated negative moods such as depression and anxiety, compulsive or addictive be- haviors, physiological arousal, physical symptoms, and po- tentially somatic disease (Lumely, Neely, & Burger, 2007; Taylor et al., 1997). Several research have demonstrated that alexithymia is commonly related to many psychosomatic syn- dromes such as gastrointestinal disorders (Galeazzi, Ferrari, Mackinnon, & Rigatelli, 2004; Porcelli & De Carne, 2001; Por- celli, De Carne, & Todarello, 2004). It is also a common feature in patients with psychoactive abuse disorders (Cleland et al., 2005; De Rick & Vanheule, 2007), Post-Traumatic Stress Dis- order (PTSD; Spitzer et al., 2007; Zlotnick et al., 2001) and classic psychosomatic disorders (Porcelli et al., 1999; Portin- casa et al., 2003). There is also consistent evidence that alex- ithymia is elevated in people with eating disorders, such as bulimia and anorexia (Beales & Dolton, 2000; Berthoz et al., 2007; De Panfilis, Salvatore, Avanzini, Gariboldi, & Maggini, 2001; Kessler, Schwarze, Filipic, Traue, & von Wietersheim, 2006; Mazzeo & Espelage, 2002; Montebarocci et al., 2006; Pinaquy, Chabrol, Simon, Louvet, & Barbe, 2003; Zonney- ville-Bender, van Goozen, Cohen-Kettenis, van Elburg, & van Engeland, 2002). In general, studies investigating alexithy- mia traits in patients with anorexia and bulimia nervosa have out- lined that they appear to have high degrees of alexithymia compared to control groups (Beales & Dolton, 2000; Corcos et al., 2000; Montebarocci et al., 2006). These studies suggest that patients with a diagnosis of Eating Disorders have difficulties with interoceptive awareness and can be categorized as alex- ithymics. In specific, they seem to present a diminished capac- ity to articulate their affective experiences and to remain dis- connected from their own subjective emotional functioning. This study aims to investigate the presence of alexithymia in a sample of subjects with a diagnosis of Eating Disorder and to analyze the psychometric properties of a new measure for as- sessing alexithymia. *Corresponding author.  A. GORI ET AL. With regard to alexithymia and its measurement, during the last few decades, several instruments have been developed with the aim of assessing and investigating its features, also in order to plan the psychological treatments (Apfel & Sifneos, 1979; Bales & Dalton, 2000; Bagby et al., 1994a, 1994b; Bagby et al., 2006; Bermond et al., 1994; Fava, Baldaro & Osti, 1980; Fava et al., 1995; Rafanelli et al., 2003). Some of the most known self-report scales, such as the Schalling-Sifneos Personality Scales (Apfel & Sifneos, 1979; Sifneos, 1986) and the MMPI Alexithymia Scale (Kleiger & Kinsman, 1980), were con- structed hastily and with little attention to standard methods of test construction. As a result, subsequent investigations have shown that these scales lack reliability and validity (Taylor and Taylor, 1997). Measurement of the alexithymia construct re- mained a major problem until the Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20; Bagby et al., 1994a, 1994b) was introduced: in fact, this self-report measure was developed following test develop- ment procedures and attention to adequate psychometric quali- ties; and this is actually one the most frequently used measure of alexithymia (Taylor et al., 2000). Although it has good psychometric properties, the TAS-20 has been recently criticized for having various shortcomings. Vorst and Bermond (2001) argued that this instrument assesses only three factors of the putative characteristics of alexithymia: difficulty identifying emotions, difficulty describing emotions, and externally oriented thinking. Because the inability to fanta- size and reduced experiencing of emotional feelings are not represented as separate factors in the TAS-20 (Kooiman, Spin- hoven, & Trijsburg, 2002), Vorst and Bermond developed the Bermond-Vorst Alexithymia Questionnaire (BVAQ; Bermond et al., 1994; Vorst and Bermond, 2001). Results demonstrate that a Principal Component Analysis of the BVAQ subscale interrelations yields a clear-cut two factor structure. This factor structure comprises an affective component and a cognitive component (Vorst & Bermond, 2001; Bermond et al., 2007). The total TAS-20 score shows correlations with the cognitive, but not with the emotional component of the BVAQ (Zech et al., 1999; Vorst & Bermond, 2001; Müller et al., 2004; Bermond et al., 2007). Both difficulty fantasizing and difficulty emotion- alizing measured within the BVAQ remained statistically un- correlated with the total TAS-20 and weakly correlated or un- correlated with the TAS-20 scales. Therefore, used as a diag- nostic instrument, the TAS-20 emphasizes the cognitive and underestimate the emotional component of alexithymia (Larsen et al., 2003). Regarding this statement, Parker et al. (2003) have argued that the TAS-20 yields three factors, which are congru- ent with and cover the salient facets of the construct. Items assessing fantasy and imaginal activity, functions which are reduced in alexithymia, were eliminated during the develop- ment of the scale primarily because they had high correlations with measures of social desirability. There is evidence to sug- gest that reduced fantasy and imaginal activity are assessed indirectly by the externally oriented thinking factor, which correlates negatively with a measure of fantasy and imaginal activity. In addition, the authors have stated that, while the first four factors correspond to the four salient features in Nemiah et al.’s (1976) definition of the alexithymia construct, emotional- izing is not part of the original definition. Therefore these addi- tional characteristics should not be considered core components of alexithymia. Moreover, they argue with regard to practicality that the BVAQ contains forty items and it takes a long time to complete. Considering these aspects the present article proposes a new, brief, and easily administered measure of alexithymia created in line with modern trends in self-report construction (e.g., Robins et al., 2001). The items of Psychological Treatment Inventory- Alexithymia Scale (PTI-AS) analyses five important dimen- sions of the construct: 1) difficulty in analyzing and identifying feelings; 2) fear of emotions; 3) difficulty in describing feelings; 4) inability to understand emotions; 5) difficulty in verbalizing sensations. The PTI-AS is part of the Psychological Treatment Inventory (Gori, Giannini, & Schuldberg, 2008) a new, multidimensional measure that was designed to include items in various domains central to planning psychological treatment and evaluating its outcome. In the PTI each scale has been grouped in various clusters that belongs to 4 main areas. The areas and clusters are: 1) Validity; 2) Resources; it includes 2 clusters: Psychological Resources and Quality of Life; 3) Clinical; which includes 2 clusters (Symptomatology and Psychological Types); 4) Psy- chological Treatment; it is composed of 4 clusters: Attachment Styles; Predominant Defense Styles; Negative Treatment Indi- cators; Psychological Mindedness. The PTI-AS has been included in the cluster Negative Treat- ment Indicators. The purpose of this research is to present evi- dence that this scale has good psychometric properties and can serve as a useful proxy for both the TAS-20 and BVAQ in a variety of research contexts. First, the factor structure and the internal consistency of the scale are established. Then some aspects of concurrent validity are investigated by relating the PTI-AS to the TAS-20 and to BVAQ scores. Some aspects of discriminant validity are evalu- ated by comparing a clinical group of patients with eating dis- orders and a part of the non clinical group. Method Participants Participants in this study were 778 persons (50.3% male, 49.7% female) with ages ranging from 18 to 63 years (M = 32.76; SD = 11.88), divided into two groups: 1) a non clinical sample composed of 743 subjects (54.9% male, 48.4% female) with a mean age of 33.7 (SD = 1.8); and 2) a clinical sample composed of 35 patients (17.8% male, 82.2 female) with a mean age of 26.33 years (SD = 9.27). The first group of par- ticipants (the non clinical sample) consisted of a convenience sample recruited for this study. The second group of partici- pants (n = 35) was composed of patients with diagnoses of Eating Disorders. These subjects were recruited in various cen- tres specializing in Eating Disorders treatments. All participants were Italian and completed the PTI Alexithymia Scale in a booklet form. Measures PTI-Alexithymia Scale (PTI-AS; Gori, Giannini, & Schuld- berg, 2008). The PTI-AS consists of 5 items, each measured on a five-point Likert scale. The aim of this instrument is to assess symptoms of alexithymia, which is denoted by difficulty in identifying feelings, difficulty in describing feelings, difficulty analyzing feelings, and impoverishment of inner emotional life (inability to understand emotions and fear of emotions), em- ploying the smallest number of items as possible. Twenty-Items Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20; Bagby et Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 232  A. GORI ET AL. al., 1994a, 1994b; Taylor & Taylor, 1997). The TAS-20 con- sists of twenty items which load on three factors. These three factors are denoted as F1 “Difficulty in identifying feelings,” F2 “Difficulty in describing feelings,” and F3 “Externally- oriented thinking”. Fifteen items are indicative of the dimen- sions of alexithymia and five are contra-indicative. The rating scales have five response categories varying from “strongly dis- agree” (1) to “strongly agree” (5). A total score is calculated by summing all items such that higher score reflect a greater level of alexithymia. Scores higher than 61 are categorized as indi- cating an alexithymic profile according to the recommendation of Taylor et al. (1997). The original TAS-20 is characterized by acceptable psychometric qualities. The reliability of the total scale equals .81, and the reliabilities of the three factors are .78, .75, and .66 (F1, F2, F3 respectively; Bagby et al., 1994). The validity of the TAS-20 is also acceptable (Bagby et al., 1994a). In this study we used the Italian version of the TAS-20 (Bressi et al., 1996). The Bermond-Vorst Alexithymia Questionnaire (BVAQ; Ber- mond et al., 1994; Vorst & Bermond, 2001). The BVAQ con- sists of 40 items, making up two parallel forms (BVAQ-20A and BVAQ-20B) with 20 items each. This self-report measure was designed to examine five putative facets and two putative dimensions of alexithymia, as described previously. Each sub- scale (“identifying,” “describing,” “analyzing,” “fantasizing,” and “emotionalizing”) consists of 8 items, measured on a five point Likert scale. The BVAQ exhibits a second-order factor structure: Two subscales (“fantasizing” and “emotionalizing”) constitute an affective dimension and three subscales (“identi- fying,” “describing,” and “analyzing”) make up a cognitive di- mension. The total score of the BVAQ-40 ranges from 40 to 200 points, with high scores indicating high proneness to alexithymia. Regarding its psychometric properties, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients range from .67 to .87 for each of the five subscales (Müller et al., 2004; Vorst & Bermond, 2001). The validity of the BVAQ is acceptable (Müller et al., 2004; Vorst & Bermond, 2001). In this study we used the Italian version of the BVAQ (Bermond et al., 2007; Ricci Bitti & Codispoti, 2002). Eating Disorders Inventory-3 (EDI-3; Garner, 2004). The EDI-3 is a self-report instrument measuring psychological traits or constructs shown to be clinically relevant in individuals with Eating Disorders. This test consists of 91 items organized onto 12 primary scales, 3 eating disorder-specific scales (Drive for Thinness -DT-; Bulimia -B-; Body Dissatisfaction -BD-) and 9 general psychological scales (Low Self-Esteem -LSE-; Personal Alienation -PA-; Interpersonal Insecurity -II-; Interpersonal Alienation -IA-; Interoceptive Deficits -ID-; Emotional Dys- regulation -ED-; Perfectionism -P-; Asceticism -A-; Maturity Fears -MF-) that are highly relevant to, but not specific to, eat- ing disorders. It also yields six composites, one that is eating-disorder spe- cific (Eating Disorder Risk -EDRC-) and five that tap general integrative psychological constructs (Ineffectiveness -IC-, In- terpersonal Problems -IPC-, Affective Problems -AP-, Over- control -OC-, and Global Psychological Maladjustment -GPCM-). The reliability coefficients of the scales range from .80 and .90, and test-retest reliability coefficients for the various composite scales are between .93 and .98. The EDI-3 provides normative information for females with eating disor- ders who are aged 13 - 53 years. Normative data are also pro- vided for the following DSM-IV-TR diagnostic groups: 1) Anorexia Nervosa-Restricting type; 2) Anorexia Nervosa-Binge- Eating/Purging type; 3) Bulimia Nervosa; and 4) Eating Disor- ders Not Otherwise Specified. The EDI-3 asks participants to indicate if items are true of them always (A), usually (U), often (O), sometimes (S), rarely (R), or never (N). In this study we used the Italian version of the EDI-3 (Giannini et al., 2008). Procedures Participants completed the Psychological Treatment Inven- tory-Alexithymia Scale (PTI-AS) in a booklet form. All par- ticipants, who voluntarily participated in this research gave also information about age, sex, gender, educational, and profes- sional activities. For the non-clinical sample (group 1), both individual and group administration procedures were used. In order to assess some aspects of concurrent validity, a part of the non-clinical sample (group 1), composed of subjects with a mean age of 33.2 years (SD = 12.3), completed the PTI-AS, the Italian version of the Bermond-Vorst Alexithymia Ques- tionnaire (BVAQ), the Italian version of Twenty-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20), and the Italian version of the Eating Disorders Inventory-3 (EDI-3). In order to evaluate some aspects of Discriminant Validity, the PTI-AS was administered to a clinical sample of 35 patients (group 2). All of these patients had received an Eating Disor- ders diagnosis and were involved in a specific treatment for Eating Disorders. The instruments were administered by the psychiatrists and psychotherapists involved in the treatment of these patients. All patients completed an informed consent form after intake assessment. Data Analysis In order to investigate the distribution of the data in the sam- ple descriptive statistics were calculated. We used factor analy- sis to identify the PTI-AS scale dimensionality, with the objec- tive of assessing the validity of the hypothesized construct. Thus, for a portion of the sample (n = 378) a series of Explora- tory Factor Analyses (EFA) with Principal Axis Factoring (PAF) were conducted in order to verify the factor structure of the PTI-Alexithymia Scale. Using the other portion of the sam- ple (n = 400) we carried out a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). In order to evaluate the model’s goodness of fit a num- ber of indices were used. Because the chi-square index is in- fluenced by sample size (Schermelleh-Engel, Moosbrugger, and Muller, 2003), two relative indices of fit were evaluated be- cause they are applicable to both large and small samples, the NNFI (Non-Normed Fit Index) and the CFI (Comparative Fit Index). Values greater than .95 for these indices are considered satisfactory (Schermelleh-Engel, Moosbrugger, and Muller, 2003). In addition, the RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Appoximation) has been used as an absolute index of fit. Reli- ability was calculated using the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (Cronbach, 1951). Aspects of concurrent validity were evalu- ated using the Pearson r coefficient. Aspects of discriminant validity was explored using ANOVA between the clinical group (n = 35) and a randomly selected sub-sample of the non- clinical group (n = 35). Statistical analysis were performed using SPSS software v. 18 and AMOS v. 6.0. Results Results of the Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) showed a one-factor structure with 71.1% of the total variance explained. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 233  A. GORI ET AL. The Factor Structure Matrix shows the correlations between variables and the scale’s factor (see Table 1). The goodness-of-fit indicators showed a good fit of the model to the data; although the chi-square was significant (χ2 = 20.30, p < .001), the others goodness-of-fit indices showed satisfactory values (CFI = .98, TLI = .95 RMSEA = .08, SRMR = .04; see Figure 1). The reliability of the scale, evaluated using the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, showed a good level of internal consistency (α = .88). Item-Total correlation values ranged from .70 (item 2) to .85 (item 5). The PTI-AS showed good levels of correlation with the Ita- lian version of the twenty-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS- 20; see Table 2). In addition correlation among the PTI-AS and the scales of the Italian version of the Bermond-Vorst Alexithymia Ques- tionnaire (BVAQ) showed good values (see Table 3). Correlation between the PTI-AS and the EDI-3 scales showed significant values: Drive for Thinness (DT) (r < .41, p < .001); Bulimia (B) (r < .34, p < .01); Body Dissatisfaction (BD) (r < .40, p < .001); Low Self-Esteem (LSE) (r < .28, p < .05); Personal Alienation (PA) (r < .45, p < .001); Interper- sonal Insecurity (II) (r < .33, p < .01); Interpersonal Alienation (IA) (r < .34, p < .01); Interoceptive Deficits (ID) (r < .39, p < .01); Emotional Dysregulation (ED) (r < .43, p < .001); Per- fectionism (P) (r < .24, p < .05); Asceticism (A) (r < .36, p < .01); Maturity Fears (MF) (r < .25, p < .05). The ANOVA results showed that the clinical group obtained higher values of Alexithymia scores than the non-clinical group. All these differences are statistically significant (see Table 4). Discussion The growing interest in the subject of alexithymia is largely due to the work of Taylor and colleagues. Their instrument, the TAS-20, has made large-scale investigation of alexithymia possible and has served to bring alexithymia to the attention of scientists and practitioners. Therefore, in addition to the TAS- 20 several measures have been developed, including the BVAQ. The aim of the present study was to investigate the psychomet- ric properties of the PTI-AS, a new, brief, measure of alexithy- mia consisting of five items. The results of this study with a large Italian-speaking adult community sample provide strong support for the validity of the one factor structure of the PTI-AS. This also confirmed the use of the total score of the scale as a dimensional measure of alexithymia. In addition, a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) of an identical one factor model using a cross-validation sample indicates a good fit of the model to the data. The internal con- sistency of the scale is excellent (a = .88), despite the very Table 1. Factor structure and content scale of the PTI-AS. Item number Item content Factor 1 Item 5 Difficulty in verbalizing sensations .85 Item 3 Difficulty in describing feelings .84 Item 1 Difficulty in analyzing and identifying feelings .84 Item 4 Inability to understand emotions .80 Item 2 Fear of emotions .70 Figure 1. Confirmatory factor analysis. Table 2. Correlation between the PTI-AS and the TAS-20 factors. TAS-20 F1 F2 F3 Total PTI-AS .70** .55** .32* .74** **p < .001; *p < .01. small number of items. Therefore, the reliability of the PTI-AS can also be supported. Regarding the concurrent validity of the PTI-AS, the pattern of correlations indicates that the PTI-AS is associated with the three factors of the TAS-20 and the various aspects of alexithymia measured by the BVAQ. The PTI-AS and the TAS-20 total correlate highly (r = .74, p < .001). Also correlations between the PTI-AS and the BVAQ total (r < .40, p < .001) and the cognitive composite factor (r = .63, p < .001) are very high. Correlation between the PTI-AS and the EDI-3 scales also showed higher values. The interest in evaluating a group of pa- tients with Eating Disorder diagnoses, is due to the fact that several studies have suggested that patients suffering from ano- rexia and bulimia have difficulty with interoceptive awareness and show high levels of alexithymia (Beales & Dolton, 2000; Berthoz et al., 2007; Corcos, et al. 2000; De Panfilis, Salvatore, Avanzini, Gariboldi, & Maggini, 2001; Kessler, Schwarze, Filipic, Traue, & von Wietersheim, 2006; Mazzeo & Espelage, 2002; Montebarocci et al., 2006; Pinaquy, Chabrol, Simon, Lou- vet, & Barbe, 2003; Speranza et al., 2005; Zonneyville-Bender, van Goozen, Cohen-Kettenis, van Elburg, & van Engeland, 2002). The current study confirms results of previous studies on the importance of alexithymia among patients presenting with an eating disorder (Corcos et al., 2000; Montebarocci et al., 2006; Speranza et al., 2005). Specifically, the total PTI-AS scores of the clinical group were significantly higher compared to those of the control group (F [1,68] = 14.13, p < .01). In line with this finding, our clinical sample showed rating scale scores signifi- cantly higher than the control group scores for the total TAS-20 score and for the TAS-20 F1 and F2 subscales; we did not find significant differences between clinical group and control group for the F3 scores (“Externally oriented Thinking”). Exploratory and Confirmatory Factor Analysis support the construct validity of the PTI-AS. In addition the PTI-AS has been demonstrated to provide very good discriminant validity, and it may be a useful diagnostic instrument in clinical contexts. A limitation of the instrument is indicated by its low correla- tions with the affective factors of the BVAQ, although accord- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 234  A. GORI ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 235 Table 3. Correlation between the PTI-AS and the BVAQ factors. BVAQ Analyzing Verbalizing Identifying Emotionalizing Fantasizing Cognitive Affective Total PTI-AS .29* .65** .44** –.12 –.07 .63** –.12 .40** **p < .001; *p < .01. Table 4. ANOVA between the two groups. CLINICAL GROUP N = 35 NON CLINICAL GROUP N = 35 M SD M SD df F p PTI-AS 13.69 4.57 10.26 2.86 1; 68 14.13 .01 TAS-20 54.57 11.94 44.37 11.92 1; 68 12.79 .01 F1 21.97 6.02 13.69 4.51 1; 68 42.45 .01 F2 15.54 4.58 13.29 4.67 1; 68 4.16 .05 F3 17.06 4.49 18.14 4.96 1; 68 .93 .34 ing with Parker et al. (2003) these additional affective charac- teristics should be considered as correlates of alexithymia rather than core features of the construct. For future studies it would be useful to further investigate the psychometric properties of the PTI-AS scale using a larger clinical sample and it would be interesting to clarify the association between eating disorders and alexithymia in order to assess the existence and the direc- tion of possible cause-effect relationships. REFERENCES Apfel, R. J., & Sifneos, P. E. (1979). Alexithymia: Concept and meas- urement. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 32, 180-190. doi:10.1159/000287386 Bagby, R. M., Parker, J. D. A., & Taylor, G. J. (1994a) The twenty- item alexithymia scale-I. Item selection and cross-validation of the factor structure. Journal of Psychosomat i c Research, 38, 33-40. doi:10.1016/0022-3999(94)90006-X Bagby, R. M., Taylor G. J., & Parker, J. D. A. (1994b). The twenty-ite- current validity. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 38, 33- 40. doi:10.1016/0022-3999(94)90006-X Bagby, R. M., Taylor, G. J., Parker, J. D. A., & Dickens, S. E. (2006). The development of the Toronto Structured Interview for Alexithy- mia: Item selection, factor structure, reliability and concurrent valid- ity. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 75, 25-39. Beales, D. L., & Dolton, R. (2000). Eating disordered patients: Per- sonality, alexithymia and implication for primary care. British Jour- nal of General Practice, 50, 21-26. Bermond, B., Clayton, K., Liberova, A., Luminet, O., Maruszewski, T., Ricci Bitti, P., Rimé B., Vorst, H. C. M., Wagner, H., & Wicherts, J. M. (2007). A cognitive and affective dimension of alexithymia in six languages and seven populations. Cognitive and Emotion, 21, 1125- 1136. doi:10.1080/02699930601056989 Bermond, B., Oosterveld, P., & Vorst, H. C. M. (1994). Bermond-vorst alexithymia questionnaire: Construction, validity and uni-dimensio- nality. Internal Report, University of Amsterdam: Faculty of Psy- chology, Department of Psychological Methods. Berthoz, S., Perdereau F., Gokart, N., Colcos, M., & Haviland, M. G. (2007). Observer- and self-rated alexithymia in eating disorders pa- tients: Levels and correspondence among three measures. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 62, 341-347. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.10.008 Bressi, C., Taylor, G. J., Parker, J. D. A., Bressi, S., Brambilla, V., Aguglia, E. et al. (1996). Cross validation of the factor structure of the 20 item toronto alexithymia scale: An italian multicenter study. Journal of Psychosomatic Re sea rch , 41, 551-559. doi:10.1016/S0022-3999(96)00228-0 Cleland, C., Magura, S., Foote, J., Rosenblum, A., & Kosanke, N. (2005). Psychometric properties of the Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20) for substance user. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 58, 299-306. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.11.002 Corcos, M., Guilbaud, O., Speranza, M., Paterniti, S., Loas, G., Stephan, P. et al. (2000). Alexithymia and depression in eating disorders. Psychiatry Research, 93, 263-266. doi:10.1016/S0165-1781(00)00109-8 Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16, 297-334. De Panfilis, C., Salvatore, P., Avanzini, M., Gariboldi, S., & Maggini, C. (2001). Alexithymia in eating disorders: A personality disturbance? Psichiatria e Psicoterapia Analitica, 20, 349-361. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2006.11.013 De Rick, A., & Vanheule, S. (2007). Alexithymia and DSM-IV person- ality disorder traits in alchoholic inpatients: A study of the relation between both constructs. Personality and Individual Differences, 43, 119-129. Fava, G. A., Baldaro, B., & Osti, R. (1980). Toward a self-rating scale for alexithymia. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 34, 34-39. Fava, G. A., Freyberger, H. J., Bech, P., Christodoulou, G., Sensky, T., Theorell, T., & Wise, T. N. (1995). Diagnostic criteria for use in psy- chosomatic research. Psychotherapy and Psychosom at ics, 63, 1-8. Garner, D. M. (2004). The eating disorder inventory-3 professional ma- nual. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources (Italian Version; Giannini, M., Pannocchia, L., Dalle Grave, R., Muratori, F., & Vig- lione, V. Eating Disorder Inventory-3. Manuale. Giunti OS—Orga- nizzazioni Speciali: Firenze 2008). Galeazzi, G. M., Ferrari, S., Mackinnon, A., & Rigatelli, M. (2004). Interrater reliability, prevalence, and relation to ICD-10 diagnoses of the Diagnostic Criteria for Psychosomatic Research in consultation- liaison psychiatry patients. Psychosomatics, 45, 386-393. doi:10.1176/appi.psy.45.5.386 Gori, A., Giannini, M., & Schuldberg, D. (2008). Mind and body to- gether? A new measure for planning treatment and assessing psy- chotherapy outcome. The International Meeting of the Society for the Exploration of Psychotherapy Integration (SEPI), Boston, 4 May 2008. Kessler, H., Schwarze, M., Filipic, S., Traue, H. C., & von Wietersheim, J. (2006). Alexithymia and facial emotion recognition in patients with eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 39, 245-251. doi:10.1002/eat.20228 Kleiger, J. H., & Kinsman, R. A. (1980). The development of an MMPI  A. GORI ET AL. Alexithymia Scale. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 34, 17-24. doi:10.1159/000287442 Kooiman, C. G., Spinhoven, P., &Trijsburg, R. W. (2002). The assess- ment of alexithymia: A critical review of the literature and a psycho- metric study of the Toronto Alexithymia Scale-20. Journal of Psy- chosomatic Research, 53, 1083-1090. Larsen, J. K., Brand, N., Bermond, B., & Hijman, R. (2003). Cognitive and emotional characteristics of alexithmia. A review of neurobio- logical studies. Journal of Psychosomatic Resea r ch , 54, 533-541. doi:10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00466-X Lumely, M. A., Neely, L. C. & Burger, A. J. (2007). The assessment of alexithymia in medical settings: Implications for understanding and treating health problems. Journal of Personality Assessment, 89, 230- 246 doi:10.1080/00223890701629698 Mazzeo, S. E., & Espelage, D. L. (2002). Association between child- hood physical and emotional abuse and disordered eating behaviors in female undergraduates: An investigation of the mediating role of alexithymia and depression. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 49, 86-100. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.49.1.86 Montebarocci, O., Codispoti, M., Surcinelli, P., Franzoni, E., Baldaro B., & Rossi, N. (2006). Alexithymia in female patients with eating disorders. Eating and Weight Disorders, 11, 14-21. Müller, J., Bühner, M., & Ellgring, H. (2004). The assessment of alexi- thymia: Psychometric properties and validity of the Bermond-Vorst Alexithymia Questionnaire. Personality and Individual Differences, 37, 373-391. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2003.09.010 Nemiah, J. C., & Sifneos, P. E. (1970). Affects and fantasy in patients with psychosomatic disorders. In O. Hill (Ed.), Modern trends in psychosomatic medicine. London: Butterworths. Nemiah, J. C., Freyberger, H., & Sifneos, P. E. (1976). Alexithymia: A view of the psychosomatic process. In O. W. Hill (Ed.), Modern trends in psychosomatic medicine (Vol. 3; pp. 430-439). London: Butterworths. Pinaquy, S., Chabrol, H., Simon, C., Louvet, J. P., & Barbe, P. (2003). Emotional eating, alexithymia, and binge-eating disorder in obese- women. Obesity Research, 11, 195-201. doi:10.1038/oby.2003.31 Parker, J. D. A., Taylor, G J., & Bagby, R. M. (2003). The 20-Item Toronto Alexithymia Scale III. Reliability and factorial validity in a community population. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 55, 269-275. doi:10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00578-0 Porcelli, P., Taylor, G. J., Bagby, R. M., & De Carne, M. (1999). Alexithymia and gastrointestinal disorders. A comparison with in- flammatory bowel disease. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 68, 263-269. doi:10.1159/000012342 Porcelli, P., & De Carne, M. (2001). Criterion-related validity of the diagnostic criteria for psychosomatic research for alexithymia in pa- tients with functional gastrointestinal disorders. Psychotherapy & Psychosomatics, 70, 184-188. doi:10.1159/000056251 Porcelli, P., De Carne, M., & Todarello, O. (2004). Prediction of treat- ment outcome of patients with functional gastrointestinal disorders by the diagnostic criteria for psychosomatic research. Psychotherapy & Psychosomatics, 73, 166-173. doi:10.1159/000076454 Portincasa, P., Moschetta, A., Baldassarre, G., Altomare, D., & Pa- lasciano, G. (2003). Pan-enteric dysmotility, impaired quality of life and alexithymia in a large group of patients meeting ROME II crite- ria for irritable bowel syndrome. World Journal of Gastroenterology, 9, 2293-2299. Rafanelli, C., Roncuzzi, R., Finos, L., Tossani, E., Tomba, E., Mangelli, L., Urbinati, S., Pinelli, G., & Fava, G. A. (2003). Psychological as- sessment in cardiac rehabilitation. Psychotherapy and Psychosoma- tics,72, 343-349 Ricci Bitti, P. E., & Codispoti, M. (2002). Alexithymia hedonic capac- ity and dysphoria. The (non) expression of emotion. In: A. J. J. M. Vigerhoets, & J. J. van Bussel (Eds.) Health and disease (pp. 32-34). Tilburg: Bohelhouwer Faculteit Sociale Wetenschappen, Catholieke Universiteit Brabant. Robins, R. W. Hendin, H. M., & Trzesniewski, K. H. (2001). Meas- uring global self-esteem: construct validation of a single-item meas- ure and the rosenberg self-esteem scale. Personality and Social Psy- chology Bulletin, 27, 151-160. doi:10.1177/0146167201272002 Schermelleh-Engel, K., Moosbrugger, H., & Muller H. (2003). Evalu- ating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and goodness-of-fit models. Methods of Psychological Research Online, 8, 23-74. Sifneos, P. E. (1973). The prevalence of “alexithymic” characteristics in psychosomatic patients. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 22, 255-262. doi:10.1159/000286529 Sifneos, P. E. (1986). The schalling-sifneos personality scale-revised. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 45, 161-165. doi:10.1159/000287942 Speranza, M., Corcos, M., Loas, G, Stephan, P., Guilbaud, O., Peretz- Diaz, F. et al. (2005). Depressive personality dimensions and alexi- thymia in eating disorders. Psychiatry Research, 135, 153-163. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2005.04.001 Spitzer, C., Vogel., M., Barnow, S., Freyberger, H. J., & Grabe, H. J. (2007). Psychopathology and alexithymia in severe mental illness: the impact of trauma and posttraumatic stress symptoms. European Archives of Psychiarty and Cli n c al Neuroscience, 257, 191-196. doi:10.1007/s00406-006-0669-z Taylor, G. J., Ryan, J. D. A., & Bagby, R. M. (1985). Toward the de- velopment of a new self-report alexithymia scale. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 44, 191-199. doi:10.1159/000287912 Taylor, G. J., & Taylor, H. L. (1997). Alexihymia. In M. McCallum & W. Piper (Ed.). Psychological mindedness. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Taylor, G. J., Bagby, R. M., & Luminet, O. (2000). Assessment of Alexithymia: self-report and observer-rated measures. In J. D. A. Parker & R. Bar-On (Eds.), The handbook of emotional intelligence (pp. 301-319). San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass. Taylor, G. J., Bagby, R. M., & Parker, J. D. A. (1997). Disorders of affect regulation: Alexithymia in medical and psychiatric illness. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511526831 Vorst H. C. M., & Bermond B. (2001). Validity and reliability of the bermond-vorst alexithymia questionnaire. Personality and Individual Differences, 30, 413-434. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00033-7 Zech, E., Luminet, O., Rimé, B., & Wagner, H (1999). Alexithymia and its measurement: Confirmatory factor analyses of the 20-item toronto alexithymia scale and the bermon-vorst alexithymia questionnaire. European Journal of P e rs o na l i ty , 13 , 511-532. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-0984(199911/12)13:6<511::AID-PER347>3 .0.CO;2-0 Zlotnick, C., Mattia, J. I., & Zimmerman, M. (2001). The relationship between posttraumatic stress disorders, childhood trauma and alex- ithymia in an outpatient sample. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 14, 177-188. doi:10.1023/A:1007899918410 Zonneyville-Bender, M. J., van Goozen, S. H. M., Cohen-Kettenis, P. T., van Elburg, A., & van Engeland, H. (2002). Do adolescent ano- rexia nervosa patients have deficits in emotional functioning? Euro- pean Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 11, 38-42. doi:10.1007/s007870200006 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 236

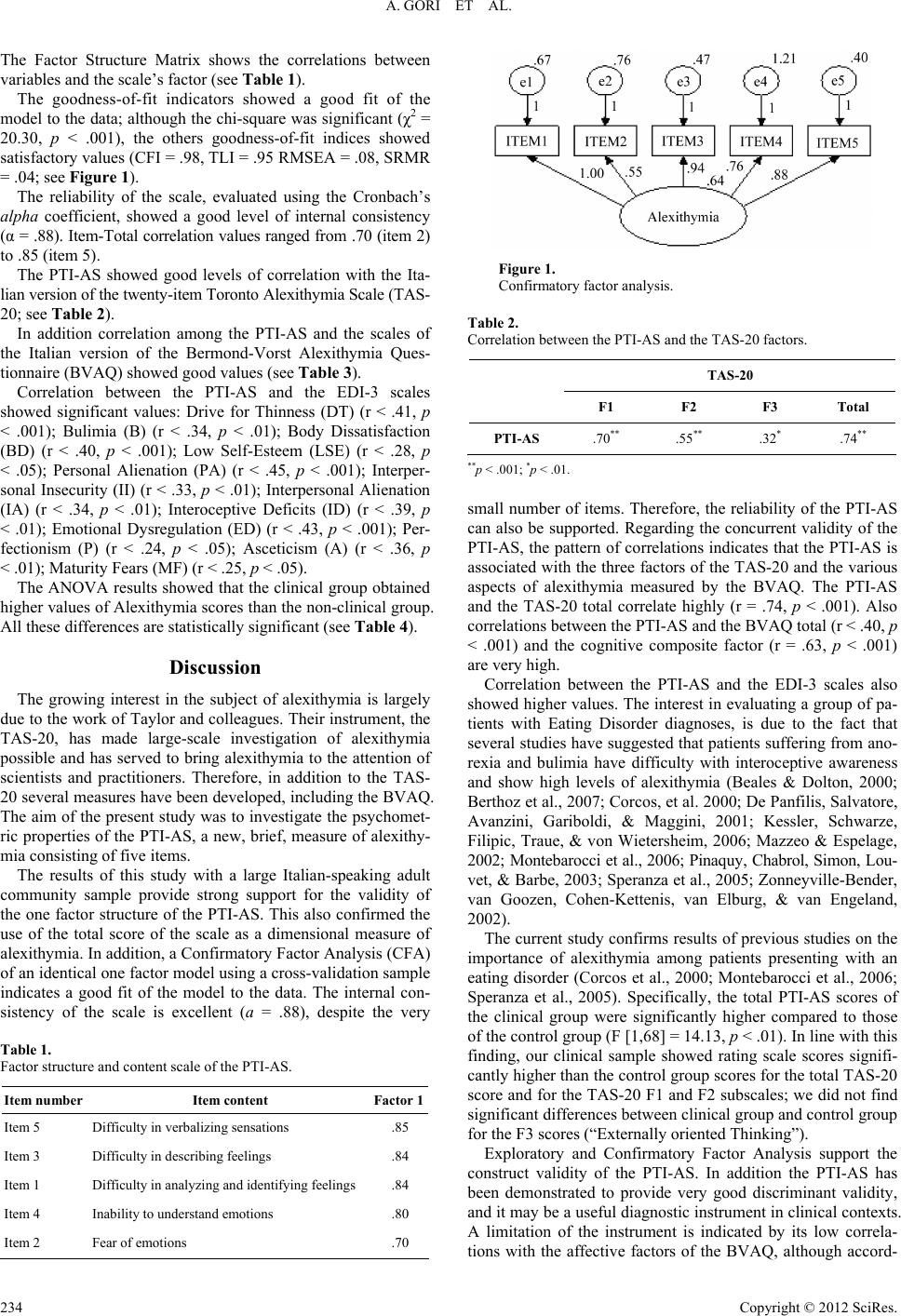

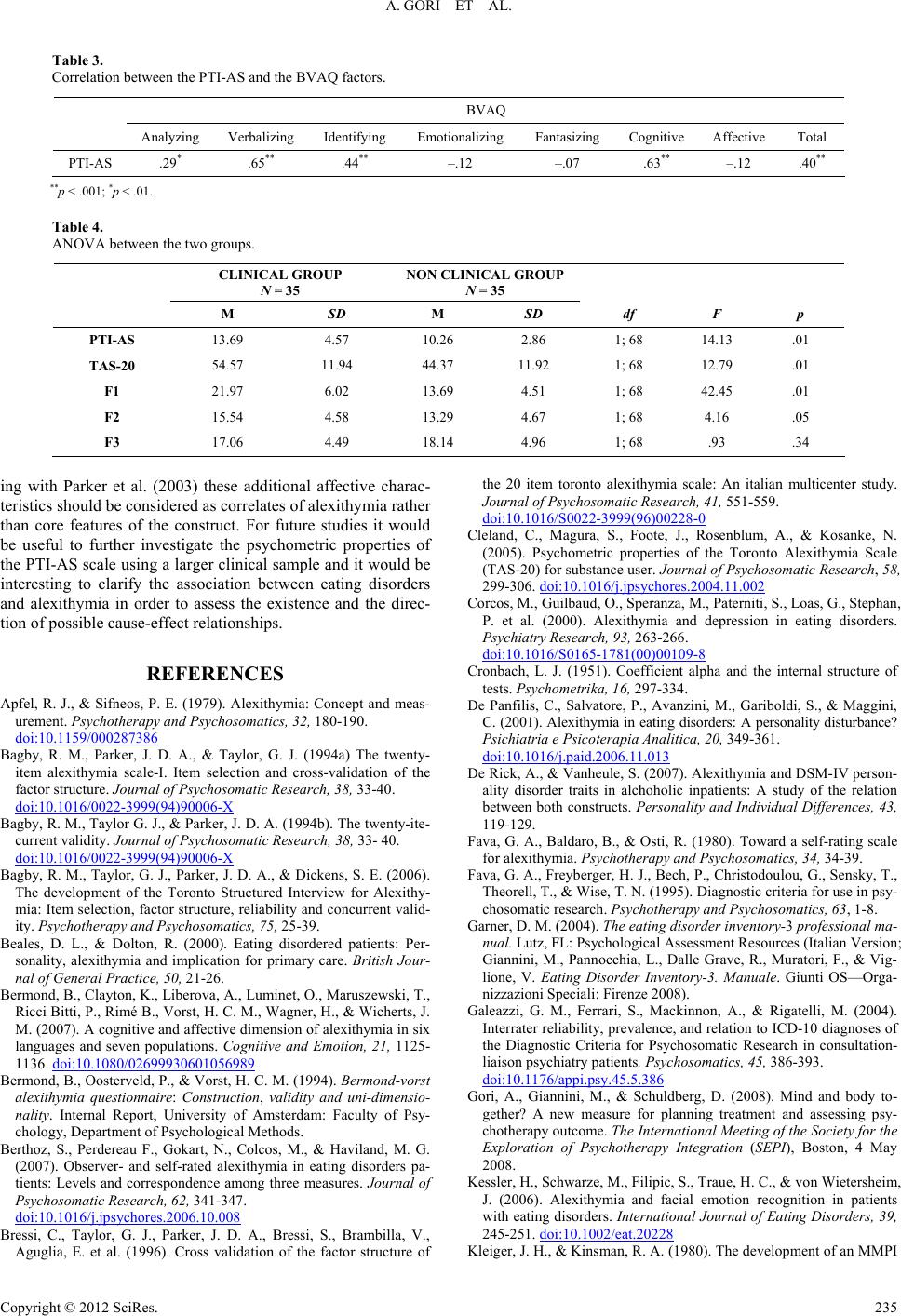

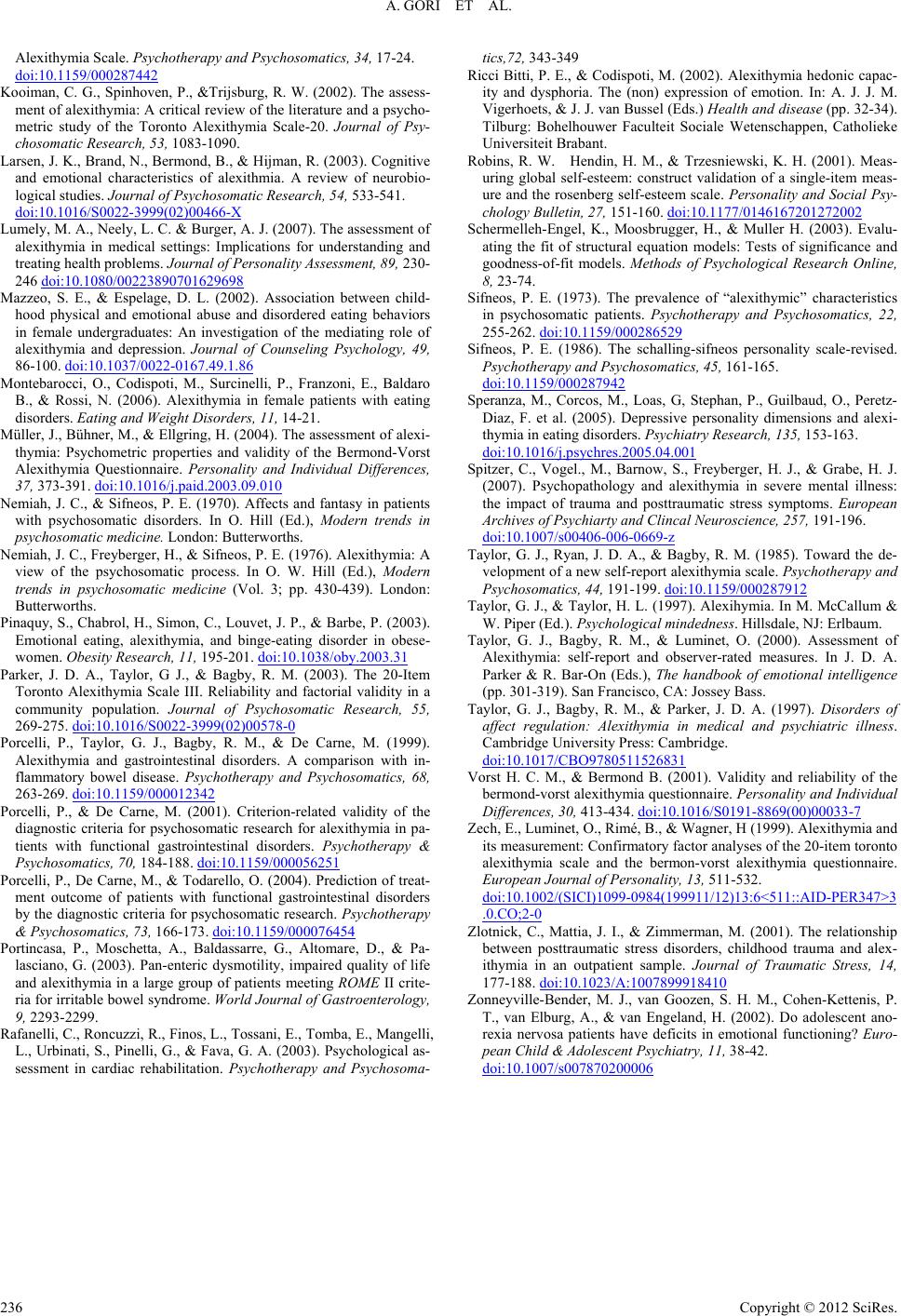

|