Advances in Applied Sociology 2012. Vol.2, No.1, 37-46 Published Online March 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/aasoci) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/aasoci.2012.21005 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 37 Foreign Workers without Work Permit in Istanbul: A Sociological Study Tülin Günşen İçli1, Hanifi Sever2 1Department of Sociology, Hacettepe University, Ankara, Turkey 2Zonguldak Karaelmas University, Zonguldak, Turkey Email: ticli@hacettepe.edu.tr, hanifisever@yahoo.com Received January 30th, 2012; revised February 28th, 2012; accepted March 13th, 2012 Economic inequality is one of the major reasons for current migration issues for both individuals and na- tions. Other significant reasons are threatening environment, natural disasters (drought, scarce resources, earthquake, etc.) and epidemic illnesses. Countries try to achieve their large-scale development plans and service plans so that international capital flows and service and goods are imported and exported as well as information exchange and migration of workforce are experienced. Certain crime types have gained a global character as a result of new world order accompained by globalisation and it moves between coun- tries. Both illegal migration and international workers without work permit are among such crime types. This study aims to identify the reasons for foreign people who came Istanbul, leading to have their pro- files. Another aim of the study is to analyse the position of people from the former Communist countries that are relatively new established as a result of new world order of 1990’s and that are experiencing a process of adoptation to the capitalist economy. Keywords: Working without Work Permit; Migration; Foreign People Introduction Today nearly 500,000 foreign people entry to and work in the EU countries illegally as a result of such factors as EU’s project on “freedom, security and justice”, economic wealth of this region and a significant gap between north and south (İçli & Sever, 2008). The question of why people with different cultural back- grounds prefer to live in different countries can be accounted for using quantative evidence within the framework of theore- tical approaches. In short, one of the frequently discussed topics within the migration theories is about those working in foreign countries without working permit. Certain crime types have gained a global character as a result of new world order accompained by globalisation and it moves between countries. Both illegal migration and international work- ers without work permit are among such crime types. EU has experienced a regional integration. It has also ex- perienced the Single European Act and Schengen Agreemant leading to elimination of internal border checks. Therefore, such topics as migration, right of asylum, visa and working permit have become frequently debated issues. Thus, the EU countries can be regarded as “target countries as they are subject to intense migration. Additionally, it should be noted that Turkey is both a target and a transition country to the EU countries for people from those countries that are ex- periencing serious problems, i.e. Afghanistan, Iraq, Pakistan, etc.). It is known that current international commercial, economic, technical, social and political collaboration has improved. Coun- tries try to achieve their large-scale development plans and service plans so that international capital flows and service and goods are imported and exported as well as information ex- change and migration of workforce are experienced. Economic, commercial and industrial development leads to wealth as well as to the need for work supply. Employers need educated and qualified workforce and when they can not meet this need lo- cally, they try to meet it through international workforce. In terms of security issues, despite the researches suggesting that international people are much more subject to criminal be- haviour (Allen, 1999; Barker et al., 2002; Chesney-Lind & Lind, 1986; de Albuquerque & McElroy, 1999; Fujii & Mak, 1980; Kelly, 1993), this study deals with developing the profiles of criminal international people in Istanbul. Employment Rights of Foreign People in Turkey The right to work is secured under the 48. Article of the con- stitution and regarded as among basic public rights in the Turk- ish legal system. It is also recognised in regard to foreign em- ployees. However, this right is limited by the 16. Article of the constitution in accordance with international legislation for for- eign employees. Within this framework, requirements and arrangements for working in Turkey for foreign people are given in the code of work permit and related regulations. Moreover, employment in different job areas is particularly organized in the related laws. Until the enforcement of the code of work permit (from 1923 to now) more than seventy legal arrangements were made in regard to foreign employment in Turkey. In former regulations there was a multi-centred and distributed structure, therefore foreign employment was not been effectively organized. In the code of work permit and related regulations, signify- cant new practices are offered in regard to foreign employment. In short, this code radically changed the conditions for work permit and built a new system for work conditions. The condi- tions offered by this new system are significant for both the foreign employees and the employers.  T. G. İÇLİ ET AL. Those who work in Turkey without bearing a work permit commit the crime of “working without permit” and those who employ these persons commit the crime of “employing illegal employees”. Related Literature Modernization Theory states that if market mechanism func- tion following free market economy principles without any in- tervention, there can be a balance between those countries from which people migrate and host countries. Therefore, migration occurs from those regions where development rate is relatively low to those regions where it is relatively high. It decreases the need for employment whereas it also decreases the need for supply (Turner, 1999; Rosenberg & Birdzell, 1992: p. 78). Mutual job market theory argues that immigrant workers are needed by developed countries (Piore, 1979). Migration changes based on the characteristics of workforce need. In other words, the aims of the immigrant workers are shaped in accordance with the economic background of the target country. Job mar- kets in target countries are categorized into several parts. Local workers (national citizens) have much more attractive jobs while immigrant workers often work in 3D jobs (dirty, dangerous and difficult). Furthermore, as a production factor immigrant em- ployee have much more flexible pattern in contrast to local work- ers (Bijak, 2006: p. 10). Employee supply and preferences can be changed and immigrant workers may be subject to much more difficult working hours and conditions than those of local work- ers (Massey et al., 2002: pp. 431-466). Richard Cloward and Lloyd Ohlin’s differential opportunity theory states that those persons of traditional societies who feel themselves underachieved are likely to search for opportunities to be succesful (Cloward & Ohlin, 1960: p. 239). Therefore, they may tend to migrate. However, those who cannot legally migrate or who cannot find a job in their native countries or who are desperate in regad to find a job may illegally migrate. Theory of inequality and unbalance emphasizes the inequali- ties and unbalance in social system. It argues that negative con- ditions lead individual to migrate, for instance inequal wage, common unemployment, etc. Parsons’ AGIL (Adaptation, Goal Attainment, Integration, Latency) formula, like the theory of inequality and unbalance, states that social integration is possible only when scarce re- sources are fairly distributed. On the other hand, Parsons’ vol- untarily act principle argues that individuals make choices about different acts taking scarce resources into account (Par- sons, 1951). Immigration means that persons think about how they can best benefit from scarce resources and then, act based on this reflection. In the rational decision-making process, an individual has the aim of improving their life quality through migration. Addi- tionally, he makes decisions over the issues of education, fi- nance, health-care and security. This process of decision-mak- ing is personal. Choosing a certain thing over the other options means thinking about expectations and gains. Therefore, migra- tion is a result of a conscious and informed process of decision- making. Parekh’s migration theory provides a totally different ac- count of migration. It uses the opportunity theory as a starting point. It argues that if there was a workforce supply in a coun- try, migration would fill this gap. However, when this supply is met or employement is limited, migration will stop and those migrants who cannot find a job in the target country will go back to their native country (Parekh, 1997: p. 40). Toynbee’s challenge and response theory (1946) adopts an approach that is very close to the Marxist thinking. It argues that each social change can be interpreted in terms of the proc- ess of challenge and response. Each individual has some degree potential energy. Given that universe is a challenging force for humans, they can be seen as creatures who resist and respond this force. For instance, they may give up living in their native lands to overcome the poverty and they keep up living in a foreign country to make money although local people will try to exclude them. International migrants as well as illegally employed persons are two significant topics that have been attracted by several disciplines (Böhm, 1998; Houben, 1999; Sohler, 1999; Messin- ger, 2000; Rechling, 2004; Tschernitz, 2004). Europa at the 1900’s experienced serious unemployment pro- blems. Therefore, citizens of the European countries migrated to the countries of New World (Australia, USA, Canada, New Zealand etc.). More than twenty-six million people were reported to migrate to the USA during the period of 1870-1920. These migrant people worked in these countries in the jobs related to transportation, communication, railway systems, etc. (Solimano, 2010). Of the people who migrated to the USA for employment during the period of 1870-1920, one-third was single, male and independent of their family members. Moreover, one fourth of these migrants were young people and their ages ranged from sixteen to forty (Solimano, 2010). Except for wars and violence acts, migration mostly occurs due to economic reasons. It is closely similar to the balance of supply-demand. Migration that occurs due to basicly economic reasons becomes attractive beacuse of higher wage in the target country, regular working hours and higher levels of life quality. Therefore, countries of new world order become better and pro- ductive in terms of technology, commerce, industry and finance. However, working conditions of migrant workers began to be less attractive over time. Although their life quality in the target country is much higher than that of native country, their wage is much lower than that of native citizens. After the 1920’s, England experienced massive migration by Irish people. More than half of Italian migrants tended to go to France and Germany. France and the Netherlands also experi- enced migration flows from Belgium. In the new world order, Canada and the USA are experiencing massive migration (Hat- ton & Williamson, 1998). In short, most countries experience migration with the aim of employment (Chiswick & Hatton, 2003). In recent times, typology of immigrants as well as target countries has changed. Countries of new world order tried to understand and deal with this fact of migration. For instance, they carried out researches on the number of illegal migrants. Although exact number of migrants cannot be known, there are ways of estimating these figures. Biffl (2002) carried out series of interviews and concluded that there are thousands of children with the age range of 6 - 15 in Australia. Another way to estimate the rate of migration is the compari- sion of figures related to illegat migrants caught by security forces. For instance, Australia decreased the number of illegal migrants in 2003. In 2004, a total of 38,530 illegal migrants were caught and this figure is 14% less than that in 2003. Illegal migrants identified are from Russian Federation, India, Moldovia Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 38  T. G. İÇLİ ET AL. and Romania. Those who illegally live in the country are from Bulgaria, Moldovia, Serbia and Montenegro (IOM, 2005). Matuschek (2002) states that there is a methodological com- plication in regard to the studies of illegally employed migrants. He also focuses on informal economy and illegal migration. Schneider developed another approach towards black econ- omy in Austria in which cash flows in the market. It is based on the estimation of spot buy of goods and services in black econ- omy (Schneider, 2003). He states that higher levels of cash flows are reflection of the expanded black economy. Therefore, the situation of illegally employed migrants in past periods could be revealed. In Polond, the rates of both registered and non-registered workers are employed in order to reveal the case of black econ- omy. In 2000, the number of registered workers was 885,000, while it was 924,000 in 2003 (Flaszyńska & Zarański, 2005: p. 68). However statistics of Polond Central Statistics Office (CSO) indicate that the number of registered employees is 12.6 million (CSO, 2007: p. 19). These rates are used in order to identify the profile of illegally employed migrants in the country. Like in the past, foreign people in the host countries work in difficult, dangerous and dirty jobs for fewer wages today. More- over, several jobs are negatively affected by migrant employees, for instance, construction, agriculture, commercial jobs, care services and domestic services (CSO, 2005: p. 14). Addition- ally, it is reported that illegal migrants are also employed at hotels and restaurants (Biletta & Meixner, 2005: p. 5). They al- so work in such jobs as interpreters, language educators, fi- nance advisors, computer specialists who are qualified workforce jobs (CSO, 2005: p. 19; Golinowska, 2005: p. 98; Kicinger & Kloc-Nowak, 2008: p. 5). Camarota (2004) argues that income of illegal migrants is less than that of local people. Moreover, two-thirds of them do not have university education. States’ visa policy may be related to illegal migration and il- legal employment. In those countries of which economy is hea- vily based on tourism income illegal migration is experienced much more frequently. Until October 2003, those from Ukraina, Belarus and Russia who entered to Poland without visa domi- nated the informal sectors (Kicinger & Kloc-Nowak, 2008: pp. 8-9). The findings of the study by Iglicka (2000) in 1995 indi- cate that there were more than 500 thousand people from U- kraine. Additionally Bartoszewics (2006: pp. 2-3) found that in 2005, 45% of 10.5 million tourists from Ukraina, Belarus and Russia came to Poland for economic purposes (for having jobs). Although research findings suggest that high levels of illegal migrants work without work permit in the target countries, offi- cial statistical figures in this regard are not so high. In order to account for this trouble, the data provided by the Ministry of La- bour and Social Policy and of Zawadzka and Zarański (2003: p. 208) were analysed to find out those foreigners who were ar- rested between 2002 and 2006 (Table 1). Hungary is one of those countries that has struggled against migration and illegal employment. During the 1990’s migration Table 1. Illegally employed foreign origin people in Poland. 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 Toplam 2080 2711 1795 1680 1718 9984 Source: Ministry of Labour and Social Policy, 2006 and Zawadzka & Zarański, 2003). in Hungary became a visible social, economic and political pro- blem. Although the number of foreigners was steady during the 1980’s, it increased during the 1990’s (Juhász, 1999: p. 4). The reason for this increase may be the war experienced during the related period of time in the Balkans. In 1991, 29,000 foreigners were caught at the Hungarian bor- der. This figure increased to 10,000 both in 1996 and 1997. It is found that 70% of the illegal migrants caught planned to use Hungary as a transition point (Juhász, 1999: p. 7). As a result of visa agreements, those from Romania, former Yugoslavia and former USSR could easily entered to Hungary. Since they cannot move to other affluent European countries, they stayed at and work in Hungary. Juhász (1999) argues that these migrants often worked in the fields of counstruction, ag- riculture, tourism, entertainment, restaurants, textile industry and independent business. The case of Thailand is similar to those of other countries. Thailand has a relatively better economy. Because of economic problems experienced in its neighbour countries such as Myan- mar and Cambodia, political instability and overpopulation, peo- ple from these countries migrate to Thailand and work there (Huguet & Punpuing, 2005). The other example for it is the mi- gration of people from Somali and Ethiopia to Yemen (de Regt, 2007). The other studies (Hatton & Williamson, 1998; IOM, 2005; Kicinger & Kloc-Nowak, 2008; Iglicka, 2000; Bartoszewics, 2006; Juhász, 1999; Huguet & Punpuing, 2005; de Regt, 2007; İçli & Sever, 2008) emphasize another significant point: those who officially and legally enter a country but do not exit. In other words, an illegal migrant may enter a country legally. Therefore, it is useful to analyse data about those who enter and exit the country in order to have a full understanding of this process. Illegal Foreigners in Turkey Turkey is both a transit country and a target country due to its geographical position and status. Therefore, its citizens have migrated to European countries and the USA to work while it is subject to illegal migration of the people from nearby countries. During the 1960’s Turkey sent workers to foreign countries to support its development. The other significant basis of Tur- key’s economy has been tourism. Since tourism was supported due to merely economic purposes, Turkey adopted relatively flexible visa procedures. Although target population for Turkey’s tourism was affluent European people, toruists have been mostly from Russia, Ukraina, Moldovia, Romania, Bulgaria and Arme- nia. However, soon the situation has become an issue of for- eigners who get income as a result of prostitution and illegal employment. This problem has led to economic distortion and transborder cash flows. Within this context, flexible visa policy that was originally developed for Turkey’s own interest has be- come in favor of people from neighbour countries. Formerly, migrants were going out and coming back in as required by visa procedures. Currently they do not have to come back their native countries and continue to work in Tur- key although their visa period is over. In other words, perma- nent illegal migrants replace the flyer migrants. This fact is clearly seen in the numerical findings given in Table 5. Istanbul is driving force of Turkey in terms of population, workforce, industralization and economic capacity. Its geopoli- tic position is a point of intersection for migration from Asia to Europa, transit transportation and commercial flows. Therefore, Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 39  T. G. İÇLİ ET AL. related data should be analysed in order to have a complete understanding of its position. Table 2 presents data given by Istanbul Police Department about foreigners who were involved in criminal and administra- tive crimes in Istanbul during the periods of 1995-2000 and 2001-2006: During the period of 1995-2007, they committed mostly the crimes of illegal employment, prostitution and visa violation (admisnistrative crime). The detailed numarical data on these crimes are given in Table 3. Table 3 indicates that the crimes of illegal employment and prostitution have increased since 1995. However, the rates of these both crimes were much lower during the period of 1995-2000. On the other hand, the crime of visa violation has significantly increased since 2001. Table 2. Foreigners who are party in criminal behavior and administrative cri- mes in Istanbul during the period of 1995-2000. Year/Crime Total 1995 4543 1996 10,017 1997 18,002 1998 12,689 1999 17,350 2000 16,047 2001 13,232 2002 10,148 2003 8753 2004 10,990 2005 9864 2006 10,307 Source: (İEM, 2008). Table 3. Distribution of frequently committed crimes by foreigners in Istanbul during the period of 1995-2007. Year/Crime Illegal Employment Prostitution Visa violation 1995 - 565 653 1996 485 1835 1295 1997 2,032 2448 1168 1998 3,738 3123 2207 1999 4,780 3013 1511 2000 2,453 1685 2033 2001 148 894 2965 2002 351 527 1561 2003 449 407 1893 2004 378 829 2195 2005 229 455 2505 2006 285 71 3582 2007 949 244 1662 Total 16,277 16,096 25,230 Source: (İEM, 2008). The findings of Turkey Statistics Institution (2008) are given in the following table in regard to foreign passengers who en- tered to and exited Turkey during the period of 2000-2007. It is clearly seen that beginning from 2000 to 2007 the number of people that exited Turkey is not as much as those who entered Turkey. As seen in the Table 4, foreign-origined people entered Tur- key but they did not exit the country. This gap may be a result of visa violance or that they get residence permit. However, it is also likely that they earn money through illegal employment in order to maintain their life. The data of Turkey Statistics Institution (TUİK) also provide the numbers of people who committed the crime of illegal em- ployment by their origin of country as well as their entrance and exit figures during the period of 2001-2007. The data presented in Table 5 suggest the following facts about people from different countries: 1) The number of people from Turkmenistan who entered Turkey had increased seven times during the period of 2000- 2007. However, the number of them who exited Turkey during the same period had increased only five times. Thus, Turkmeni- stan is one of the countries whose citizens mostly come to Tur- key. 2) The number of people from Georgia that entered Turkey had increased six times in 2007 on the contrary to the figure of 2000. 3) The number of people from Russian Federation, Bulgaria and Iran that entered Turkey had increased four times in 2007 on the contrary to the figure of 2000. The increase for the same period for people from Belarus is nearly ten times. Methodology In the study, the case of people who legally or illegally en- tered to Turkey and arrested because of illegal employment between January 2004 and December 2007 was analysed. Since all individual data were accessed, no sampling was employed. Data were analysed and descriptive study was carried out. The data were presented as tables of one-way frequency. All participants of the study committed the crime of illegal employment in Turkey. Additionally, some participants com- mitted the crime of visa violence or delibaretely injury or prop- erty damage, etc. Majority of them legally entered to Turkey. However, touristic or student visa bearers cannot have work permits. Table 4. Distribution of foreigners who entered and exited Turkey during the period of 2001-2007. Passenger/Year Entry Exit 2000 10,428,153 9,991,004 2001 11,619,909 11,276,531 2002 13,248,176 12,921,982 2003 13,956,405 13,701,419 2004 17,548,384 17,202,996 2005 21,124,886 20,522,621 2006 19,819,833 19,275,948 2007 23,340,911 23,017,081 Total 131,125,657 127,909,582 Source: (TUIK, 2008). Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 40  T. G. İÇLİ ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 41  T. G. İÇLİ ET AL. Therefore, a total of 1841 people who were arrested due to illegal employment in Istanbul during the years of 2004, 2005, 2006 and 2007 participated in the study and their files were accessed. Their profiles were developed including their gender, age and nationality. Additionally, other crimes committed by them are also analysed, specificially concerning place of crime. Results A total of 1841 people were arrested by either police or gen- darmerie due to illegal employment in Istanbul during the pe- riod of 2004-2007. Since in order to work in Turkey, a for- eigner has to have a work permit, they were deported due to violation of affiliated administartive laws. As seen in the Table 6, the number of illegally employed foreign people was increased from 378 in 2004 to 949 in 2007. As seen in the Table 7, the majority of the participants are male (61.6%). Citizens of twenty-four different countries were arrested by police or gendarmerie due to illegal employment in Istanbul during the period of 2004-2007. The rate of Asian people who committed crimes (legal employment and another crime) is found to be 75.5%. The rates of those from Europa and other continents are found to be 24.3% and 0.2%, respec- tively. In terms of orgin of country, it is found that people from the following countries often committed crimes in İstanbul: Turk- menistan (24.8%), Azerbaijan (17.3%) and Georgia (13.3%). Majority of the participants as seen in Table 8 committed the crime of illegal employment and were deported (72.9%). Only 1.8% of them illegally entered to Turkey. However, those who legally entered Turkey also committed several crimes. 23% of the participants committed visa violation while illegally employed. Thus, they committed two distinct crimes that require deplora- tion. In Turkey, foreign origin people are deported when they com- mitted crimes that can be either judicial or administrative crimes. In terms of crimes committed by the participants, it is found that only 4.1% of the participants committed judicial crimes in addition to the crime of illegal employment. The remaining individuals were deported due to committing the administratibe crimes. More than half of the foreigners who committed a crime were arrested by police (69.4%). 30.6% of them were arrested by gendarmerie. These rates also indicate the fact that they committed crimes in urban areas (Table 9). In terms of age distribution of the participants (Table 10), it is seen that more than half of them were in the age range of 19 - 30 (59.8%). It is followed by those with age range of 31 - 40. A considerable point in age distribution is that foreign origined Table 6. Number of illegally employed foreign people during the period of 2004-2007. Year Number of illegally employed foreigners 2004 378 2005 229 2006 285 2007 949 Total 1841 Table 7. Distribution of illegally employed foreigners by their gender and country of origin during the period of 2004-2007 (percentage). Gender n % Male 1134 61.6 Female 703 38.2 Travesty 4 0.2 Total 1841 100.0 Continent Asia 1390 75.5 Europa 449 24.3 Africa 1 0.1 America 1 0.1 Total 1841 100.0 Illegal foreign workers Turkmenistan 457 24.8 Azerbaijan 318 17.3 Georgia 244 13.3 Bulgaria 143 7.8 Ukraine 114 6.2 Russian Federation 113 6.1 Moldovia 111 6 Iran 99 5.4 Romania 78 4.2 Armenia 58 3.2 Belarus 37 2 Uzbekistan 35 1.9 Tunusia 6 0.3 Kyrgyzstan 6 0.3 Afghanistan 4 0.2 Lebanon 3 0.2 Philliphines 3 0.2 Mongolia 3 0.2 Israil 2 0.1 Macedonia 2 0.1 China 2 0.1 England 1 0.1 Canada 1 0.1 Kenya 1 0.1 Total 1841 100 Table 8. Secondary types of crime committed by those illegally employed foreign- ers in Istanbul during the period of 2004-2007. Crime types n % Only illegal employment 1342 72.9 Visa violation 423 23 Illegal entrance 34 1.8 Property damage 13 0.7 Intentionally injury 10 0.5 Forgery 7 0.4 Loot 6 0.3 Rape 3 0.2 Robbery 2 0.1 Fraud 1 0.1 Total 1841 100.0 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 42  T. G. İÇLİ ET AL. Table 9. Law enforcement force that arrested illegally employed foriegners in Tur- key during the period of 2004-2007. Law enforcement force n % Police 1278 69.4 Gendarmerie 563 30.6 Total 1841 100.0 Table 10. Age distribution of foreigners who were illegally employed in Istanbul during the period of 2004-2007. Age n % Younger than 18 116 6.3 19 - 30 1101 59.8 31 - 40 391 21.2 41 - 50 176 9.6 Older than 50 57 3.1 Total 1841 100.0 juveniles younger than 18 years old were also illegally employed in Istabul (6.3%). As seen in the Table 11, 82.5% of the participants were ille- gally employed in the Europa side of Istanbul. Istanbul has a total of thirty-nine districs. Illegal employment is found to be committed in thirty of these districts. Those districts where illegal employment is frequent are Fatih (27%), Büyükçekmece (8.9%) and Çatalca (6.1%). In terms of gender distribution (Table 12), it is found that 61.6% of the participants were male. It is also found that 46.5% of females worked illegally in Fatih. It is followed by Şişli (12.4%) and Kadıköy (8.1%). Males are found to be illegally employed in Fatih (15%), Büyükçekmece (12.3%) and Çatalca (8.9%). The other interesting finding of the study is that males are much more common than females in regard to the participants: Turkmenistan (71.6%), Azerbaijan (86.5%), Georgia (72.1%), Iran (98%), and Romania (83.3%). On the other hand, females from Ukraina (96.5%) and Russia (96.5%) are much more common. All people from Belarus are found to be females (Ta- ble 13). Conclusion Research suggests that foreign origined people become vic- tims of crime in the countries where they migrate (Barker et. al., 2002; Bentley & Page, 2001; Fujii & Mak, 1980; İçli, 2007; Pizam & Mansfeld, 1996; Prideaux, 1994; Tarlow, 2000; Walm- sley et al., 1983). However, the current study has found that 27.1% of 1841 foreign origined people committed crimes against the state or local people in addition to the crime of illegal em- ployment. It clearly shows that migrants are not only victims of criminal behavior but also the agents of criminal behavior. As stated earlier, the number of people who were illegally employed in Istanbul during the period of 2004-2007 is 1841. In 2007, the crime of illegal employment increased. The basic within the project of KADIM (struggle against off-the book Table 11. Areas of illegal employment crime committed by foreign origin people in Istanbul during the period of 2004-2007. Crime area n % Asia side 324 17.5 Europa side 1518 82.5 Total 1841 100.0 Related district n % Fatih 497 27 Büyükçekmece 163 8.9 Çatalca 113 6.1 Şişli 105 5.7 Eyüp 98 5.3 Kadıköy 96 5.2 Ümraniye 77 4.2 Silivri 68 3.7 Küçükçekmece 61 3.3 Gaziosmanpaşa 58 3.2 Other 505 27.4 Total 1841 100.0 Table 12. Places of crimes committed by foreign origin people based on gender in Istanbul during the period of 2004-2007. Male Female District/Gender n % n % Fatih 170 15 327 46.5 Büyükçekmece 140 12.3 23 3.3 Çatalca 101 8.9 12 1.7 Şişli 18 1.6 87 12.4 Eyüp 85 7.5 12 1.7 Kadıköy 39 3.4 57 8.1 Ümraniye 70 6.2 7 1 Silivri 43 3.8 25 3.6 Other 468 41.3 153 21.7 Total 1143 100.0 703 100.0 Table 13. Gender distribution of foreigners who were illegally employed in Is- tanbul during the period of 2004-2007. Male Female Country/Gender n % n % Turkmenistan 327 71.6 130 28.4 Azerbaijan 275 86.5 41 12.9 Georgia 176 72.1 68 27.9 Bulgaria 67 46.9 76 53.1 Ukraina 4 3.5 110 96.5 Russia 4 3.5 109 96.5 Moldovia 44 39.6 66 59.5 Iran 97 98 2 2 Romania 65 83.3 13 16.7 Armenia 47 81 11 19 Belarus - - 37 100.0 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 43  T. G. İÇLİ ET AL. reason for this increase is thought to be the attempts made em- ployment) to reveal the related cases. Within the KADIM pro- ject, Istanbul Governorship coordinates the efforts of security forces, employment inspectors, and other related institutions. Therefore, concrete steps are taken to struggle against illegal employment. As stated in the literature review, Parekh argues that if there is a workforce supply in a country, migration will fill this gap. However, when this supply is met or employement is limited, migration will stop and those migrants who cannot find a job in the target country will go back to their native country. For the case of İstanbul, it can be suggested that certain job types need cheaper workforce in regard to both gender. Citizens of under- developed countries earn less money in their native countries so that job opportunities in other countries attract them. Particu- larly in Istanbul there is no employment limitation or the end of demand. Therefore, the participants seemed not to go back their own country although they could not find a job. Rather, they illegally worked until they were deported. It is found that illegal migrants are mostly from Turkmeni- stan (24.8%), Azerbaijan (17.3%) and Georgia (13.3%). The rates of people from these three countries exceed the half of the total number of participants. The other countries of which peo- ple come to Turkey frequently are mostly the former USSR countries or those that have historical ties with Turkey. At this point it is necessary to take Parsons’s theory into ac- count suggesting that inequalities and unbalanced social struc- ture within social system cause to migration and illegal work- force. In fact, economic unfairness and increasing rates of unem- ployment in the source countries result from transition econo- mies. Countries of the former USSR have been experiencing very clear political conflicts. Also the people of these countries do not have a uniform tendency in regard to economic systems in that some of them prefer to have western type of economic structure while the others prefer to have Communist economy structure. These facts have led to instable market economy in these countries (Sever & Arslan, 2008). Luckoo and Tzvekova (2002) and Hughes (2002) argue that sixty million people (40% of the total population) experienced serious poverty in Russia in 2000. After the collapse of former political regime in this coun- try after the 1990’s, 6.5 million women became unemployed. The other source countries are Ukraina and Moldovia. In Mol- dovia, 90% of people earn less than two dollars per day. After the collapse of communism, the income level of Moldovia de- creased around 70% (Levehenco, 1999; Barrwell et al., 2000). Therefore, the reason for high levels of people (75.5%) who came from Asian countires and were illegally employed in Istanbul seems to be economic problems experienced in source countries. Additionally, following the differential opportunity theory, it can be argued that those who feel themselves under- achieved may tend to work in other countries adopting a ra- tional decision-making approach to reach their goals. Therefore, it is possible to state that the foreign origined people who came to Turkey are those who cannot realize their goals and are eco- nomically unsuccesful persons. Moreover, following the chal- lenge and response theory, it can be argued that those individu- als who cannot enjoy the scarce sources of their own countries challenge this situation and respond it thorugh migration to a country. Additionally, other researches indicate that illegally employed persons are mostly from neighbor countries or nearby countries or those countries that experience visa exemption (Hatton & Williamson, 1998; IOM, 2005; Kicinger & Kloc-Nowak, 2008; O’Rourke & Williamson, 2000; Iglicka, 2000; Bartoszewics, 2006; Juhász, 1999; Huguet & Punpuing, 2005; de Regt, 2007) Similarly, those who committed the crime of illegal employ- ment in Turkey are from neighbor countries, or from nearby countries or from those countries that experience visa exemp- tion. Majority of the foreigners who worked illegally came to Turkey holding visa. It is found that only 1.8% of the partici- pants entered Turkey do not have visa. Although majority of them legally entered Turkey, 23% of the participants violated visa requirement during the period of illegal employment. Thus, they committed two distinct crimes that legally require deporta- tion. By 2007, the rates of both illegal employment and of visa violation significantly increased. Formerly, migrants were go- ing out and coming back as required by visa procedures.Today, they do not do so. In other words, permanent illegal migrants replace the flyer migrants. Illegally employed foreigners are mostly arrested in police areas (69.4%). It is not surprising in that commercial institu- tions are basicly in these areas. However, as seen in Table 12, in 2007 the rate of arrested foreigners who were illegally em- ployed in gendarme areas increased. The basic reason for this finding seems to be the establishment of production sites in these areas. 59.8% of the participants are in the age range of 19-30. These people who cannot take part in workforce or feel that they could not gain the sufficient reward for their labour in their own countries came to Istanbul to gain the material rewards that are higher on the contrary to those in their country of origin but less than those of local people. 82.5% of the participants committed the crime of illegal em- ployment in the Europa side of Istanbul because this region is much more developed in terms of industry, commerce and working conditions on the contrary to the Anatolian side. Istanbul has a total of thirty-nine districs. Illegal employment is found to be committed in thirty of these districts. Those dis- tricts where illegal employment is frequent are Fatih (27%), Büyükçekmece (8.9%) and Çatalca (6.1%). Fatih is a developed district in terms of entertainment, international commerce, etc., while Büyükçekmece and Çatalca is developed as a site for factories. It seems that workfoce demand is met through illegal workers. 46.5% of females worked illegally in Fatih. It is followed by Şişli (12.4%) and Kadıköy (8.1%). Night clubs, entertainmet sector as well as international commercial firms are extensive in the districts of Fatih and Şişli. Males are found to be illegally employed in Fatih (15%), Büyükçekmece (12.3%) and Çatalca (8.9%). More than half of the people from twenty-four coun- tries who were arrested due to illegal employment are males (61.6%). As stated in the theory of double labor market, males mostly work in those jobs which require physical power. Another considerable finding of the study is that males are much more common than females in regard to these countries: Turkmenistan (71.6%), Azerbaijan (86.5%), Georgia (72.1%), Iran (98 %), and Romania (83.3%). On the other hand, females from Ukraina (96.5%) and Russia (96.5%) are much more com- mon. All people from Belarus are found to be females. This finding reflects the conclusions of Luckoo and Tzvekova’s (2002) and Hughes’ (2002) studies in that women experience serious problems in participating in workforce in their countries leading Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 44  T. G. İÇLİ ET AL. to migration to Turkey and they tend to work in those jobs that are easy ways to earn money. Those from Turkmenistan, Azer- baijan, Georgia and Iran are mostly males and they seem to be employed in difficult jobs in suburbs. Both male and female illegal workers earn less money. There are three different methods of identifying net migra- tion rate. One of them is estimation that refers to the analysis of the findings of survey questionnaires and of police records. However, it is thought that estimation is very hard to employ. Because all cases of illegal employment occurred in Istanbul during the years of 2004, 2005, 2006 and 2007 are included in the study. However, it is not possible to argue that this figure reflects the whole situation. In other words, there may be those who do not have any official record. Therefore, net migration rate can only be an estimation. In conclusion, both illegal migration and illegal employment are two major problems of current periods of time like it was in the past. Given that the gap between underdeveloped countries and developed countries in terms of living standards and poten- tial opportunities, migration will increase. It is useful to analyse the conditions of migrants as “pre-mi- gration” and “post-migration” in order to have a complete un- derstanding of the reasons for mobility of people. Therefore, narration of migrants may be helpful. Additionally, description of environmental conditions, social patterns (etnicity, cultural elements, etc.), socio-economic analyses, violence cases, discri- mination practices etc. is also significant. Moreover, the rela- tionship between the reasons for migration and social patterns should be analysed in order to have much more complete un- derstanding of migration and illegal employment. REFERENCES Allen, J. (1999). Crime against international tourists. NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research, Number 43. URL (last checked 10 May 2009). http://www.lawlink.nsw.gov.au/bocsar/ Barker, M., Page, S. J., & Meyer, D. (2002). Modelling tourism crime: The 2000 America’s cup. Annals of Tourism Research, 29, 762-782. doi:10.1016/S0160-7383(01)00079-2 Bartoszewicz, W. (2006). Aims, motives and forms of visits to Poland in 2005. Institute of Tourism: Warsaw. URL (last checked 15 May 2009). http://www.intur.com.pl/inne/celemotywy2005.pdf Barrwell, S., Phillips, R., & Schmiechen, M. (2000). Trafficking in wo- man: Moldova and Ukraine, URL (last checked 20 May 2009). http://www.minadvocates.org Bentley, T. & Page, S. (2001). Scoping the Extent of Tourist Accidents. Annals of Tourism Research, 28, 705-726. doi:10.1016/S0160-7383(00)00058-X Biffl, G. (2002). Integration of Foreigners and their Effects on the La- bour Market in Austria. In G. Biffl (Ed.), Illegal Employment (pp. 346-350). Vienna: Austrian Institute for Economic Research. Bijak, J. (2006). Forecasting ınternational migration: Selected theories, models and methods. Warsaw: Central European Forum for Migra- tion Research. Biletta, I. Y., & Meixner, M. (2005). EIRO thematic feature—Industrial relations and undeclared work. Dublin: European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions. URL (last checked 10 April 2010). http://www.eurofound.europa.eu/pubdocs/2005/135/en/1/ef05135en.pdf Böhm, H. (1998). Refugee policy in Austria under the aspect of the border surveillance and support operation of the austrian federal army. Master Thesis, Vienna: University of Vienna. Camarota, S. A. (2004). The high cost of cheap labor, illegal immigra- tion and the federal budget. Washington DC: Center for Immigration Studies. Chesney-Lind, M., & Lind, I. (1986). Visitors as victims: Crimes against tourists in Hawaii. Annals of Tourism Research, 13, 167-191. doi:10.1016/0160-7383(86)90036-8 Chiswick, B., & Hatton, T. (2003). International migration and the integration of labor markets. In M. D. Bordo, A. M. Taylor & J. G. Williamson (Eds.), Globalization in historical perspective (pp. 65-117). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. Cloward, R., & Ohlin, L. (1960). Delinquency and opportunity. New York: The Free Press. CSO. (2005). Unregistered work in Poland in 2004. Warsaw: Central Statistical Office. De Albuquerque, K., & McElroy, J. (1999). Tourism and crime in the Caribbean. Annals of Tourism Research, 26, 968-984. doi:10.1016/S0160-7383(99)00031-6 De Regt, M. (2007). Migration to and through Yemen: The case of migrant domestic workers. Migration and Refugee Movements in the Middle East and North Africa—The Forced Migration & Refugee Studies Program. Cairo: The American University in Cairo. Flaszyńska, E., & Zarański, A. (2005). Employ legally and work legally: The work of the services controlling the legality of employment in 2004, Rynek Pracy, 68-86. Fujii, E., & Mak, J. (1980). Tourism and crime: Implications for re- gional development policy. Regional Studies, 14, 27-36. doi:10.1080/09595238000185031 Golinowska, S. (2005). Changes in labour and the situation on the labour market. In F. Ebert (Eds.), Poland 2005: Social report (pp. 77-102). Stiftung: Warsaw. Hatton, T .J. & Williamson, J. G. (1998). The age of mass migration. Causes and economic impact. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Houben, K. (1999). Social and Economic Rights of Illegal Migrants in Austria and Belgium. Master Thesis, Vienna: European Master’s De- gree in Human Rights and Democratization. Hughes, D. (2002). Trafficking for sexual exploitations: The case of Russian Federation. Geneva: IOM. Huguet, J. W. & Punpuing, S. (2005). International migration in Thai- land. Bangkok: International Organization for Migration, Regional Office. Iglicka, K. (2000). Ethnic division on emerging foreign labour markets in Poland during the transition period. Europe-Asia Studies, 52, 1237- 1255. doi:10.1080/713663127 IOM. (2005). Illegal Immigration in Austria, “Illegally Resident Third Country Nationals in the EU Member States: State Approaches to- wards Them and Their Profile and Social Situation,” Vienna. Juhász, J. (1999). Illegal Labour Migration and Employment in Hun- gary. Geneva: International Migration Papers, ILO Migration Pro- gramme. İçli, T. G. (2007). Kriminoloji. Ankara: Seçkin Yayınları. Içli, T., & Sever, H. (2008). Profiling foreigners ınvolved in crime: The case of İstanbul. Conference of Environmental Criminology and Crime Analysis, 17-19 March 2008, İzmir. IEM. (2008). Istanbul Emniyet Mudurlugu verileri. URL (last checked 13 February 2009). http://www.iem.gov.tr Kelly, I. (1993). Tourist destination crime rates: An Examination of cairns and the gold coast, Australia. The Journal of Tourism Studies, 4, 2-11. Kicinger, A., & Kloc-Nowak, W. (2008). Combating the illegal em- ployment of foreigners in the enlarged EU: The case of Poland. Warsaw: CEFMR Working Paper, Central European Forum for Mi- gration and Population Research. Levehenco, K. (1999). Legal study on the combat of trafficking in wo- man for the porpose of forced prostitution in Ukraine. Vienna: L.B.Ins. of Human Rights. Luckoo, E., & Tzvekova, M. (2002). Combating trafficking in Persons: A Directory of Organizations. London: CHANGE. Massey, D. S., Arango, J., Hugo, G., Kouaouci, A., Pellegrino, A., & Taylor, E. J. (1993). Theories of international migration: Review and appraisal. Population and Development Review, 19, 54-77. Matuschek, H. (2002). Methodological problems of measuring illegal employment and migration. In G. Biffl (Ed.), Integration of foreign- ers and their effects on the labour market in Austria, (pp. 351-361) Vienna: UWT. Messinger, I. (2000). Illegalised refugee adolescents alone in Vienna. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 45  T. G. İÇLİ ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 46 Possibilities and limits of sociopedagogic work. Master Thesis, Vi- enna: University of Vienna. Ministry of Labour and Social Policy. (2007). Control of legality of employment 2006. Warsaw: Department of the Labour Market, Min- istry of Labour and Social Policy. O’Rourke, K., & Williamson, J. (2000). Globalization and history. The evolution of a nineteenth-century economy. Cambridge: MIT Press. Parekh, B. (1997). Dilemmas of a multicultural theory of citizenship. Constellations, 4, 54-63. doi:10.1111/1467-8675.00036 Parsons, T. (1951). The social system. New York: Free Press. Piore, M. J. (1979). Bird of passage: Migrant labour in ındustrial so- cities. Cambridge: Cambridge University. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511572210 Pizam, A. & Mansfeld, Y. (1996). Tourism, crime and international se- curity issues. Chichester: Wiley. Prideaux, B. (1994). Mass tourism and crime: Is there a connection? A study of crime in major Queensland tourism destinations. Tourism Research and Education Conference, Queensland, 251-260. Rechling, D. (2004). Paid domestic work: Aspects of the environment of illegalised migrant women—Structural framework—Case study. Mas- ter Thesis, Vienna: University of Vienna. Rosenberg, N. & Birdzell, L. E. (1992). How the west grew rich: The economic transformation of the ındustrial world. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data, New York: Basic Boks Inc. Schneider, F. (2003). The extent of informal economy in the year 2003 in Germany, Austria and Switzerland—Further increase of the sha- dow economy. Universität Linz, 1-16. URL (last checked 13 Febru- ary 2005). http://www.economics.uni-linz.ac.at/Schneider/PfuschOeDCH2003.pdf Sever, H., & Arslan, S. (2008). İnsan Borsası. Ankara: Adalet Yayınları. Sohler, K. (1999). On the new formulation of inner security policy in the context of immigration control in Austria 1989-1999. Master Thesis, Vienna: University of Vienna. Solimano, A. (2010). International migration in the age of globaliza- tion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Tarlow, P. (2000). Creating safe and secure communities in economi- cally challenging times. Tourism Economics, 6, 139-149. doi:10.5367/000000000101297532 Tschernitz, A. (2004), The development of organised criminality in austria in the last 10 years with special attention to smuggling of human beings. Ph.D. Thesis, Graz: Karl-Franzens-Universität. Toynbee, A. J. (1946). A study of history. Oxford: Oxford University Press. TUİK. (2008). TUİK verileri. URL (last checked 28 June 2010). http://www.tuik.gov.tr TUİK. (2010). 2009 Hane Halkı İşgücü İstatistikleri. URL (last checked 28 June 2010). http://www.tuik.gov.tr Turner, B. S. (1999). Classical sociology. London: Sage Publications. Walmsley, D. Boskovic, R. & Pigram, J., (1983), Tourism and crime: An Australian perspective. Journal of Leisure Research, 15, 136-155 Yalçın, C. (2004). Göç Sosyolojisi. Ankara: Anı Yayıncılık. Zawadzka, G. & Zarański, A. (2003). Control of the legality of employ- ment in 2002. Rynek Pracy, 201-215.

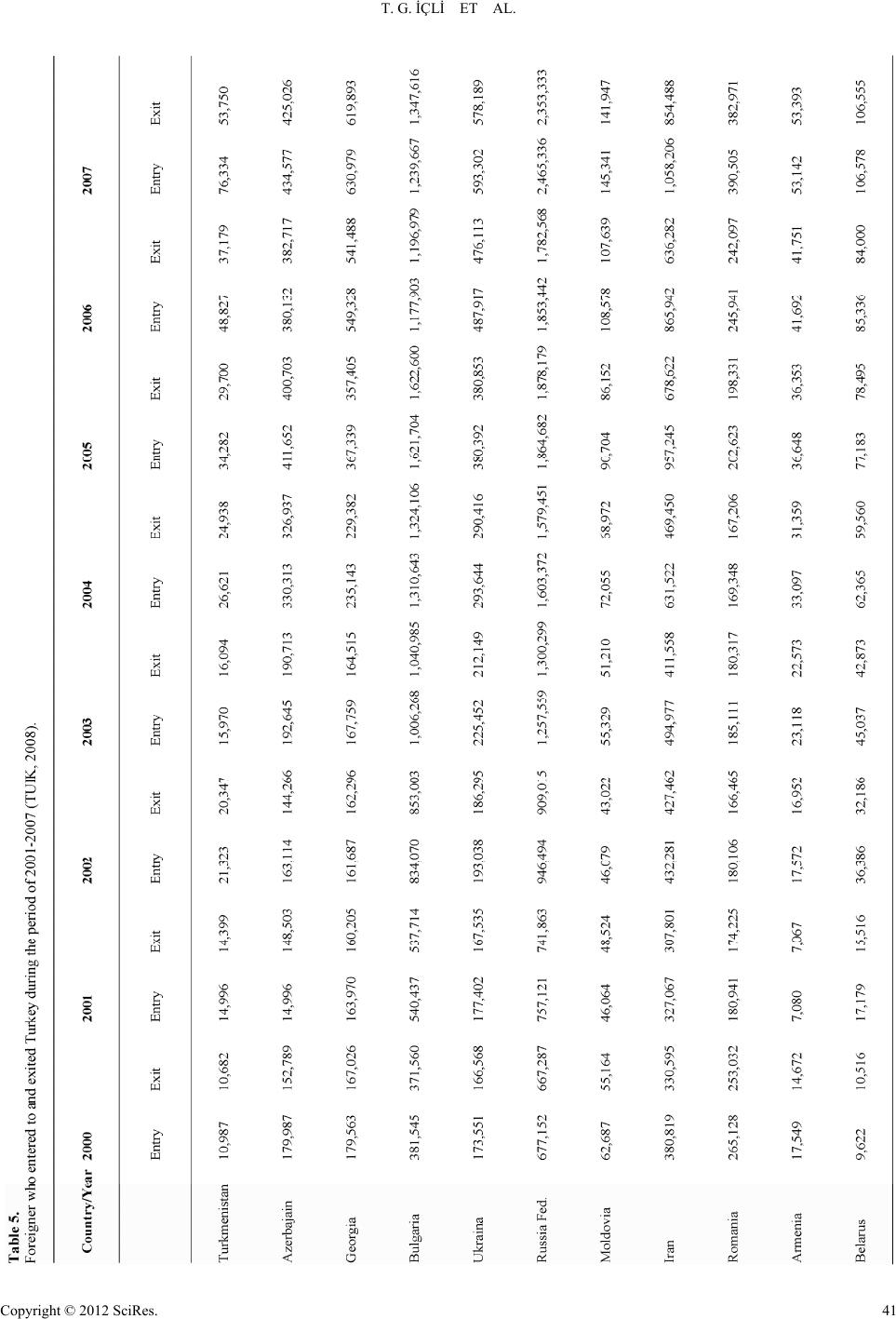

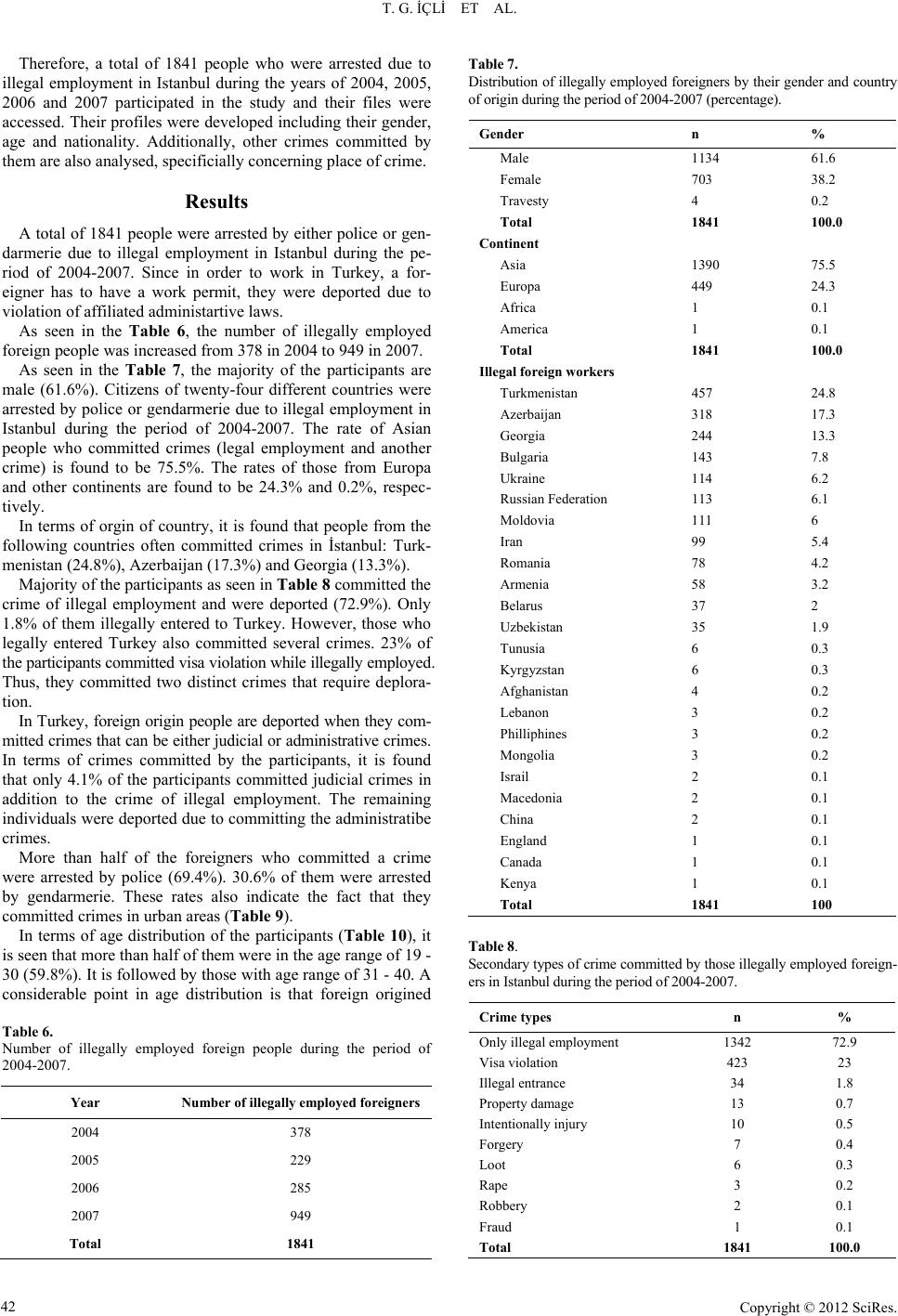

|