Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

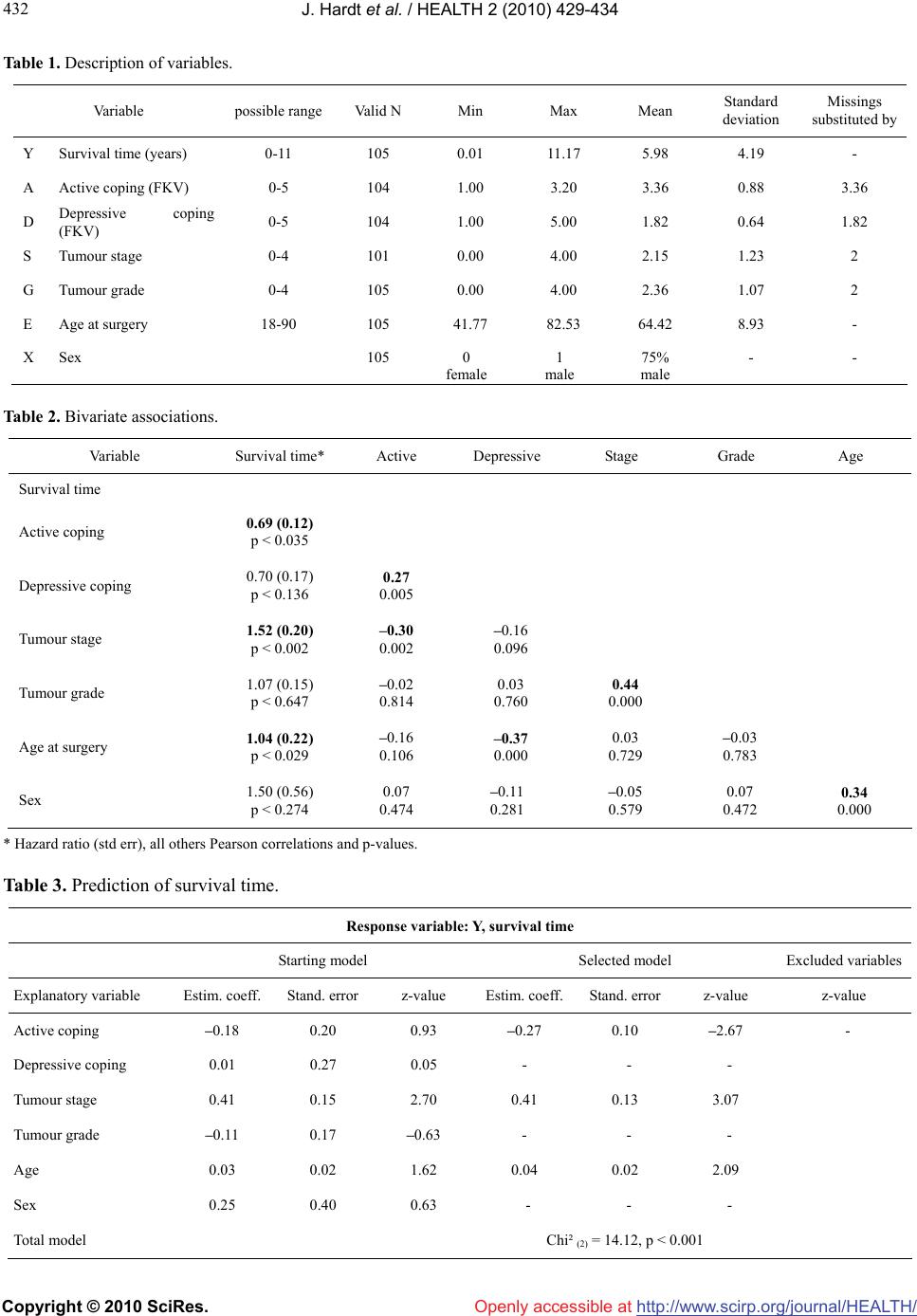

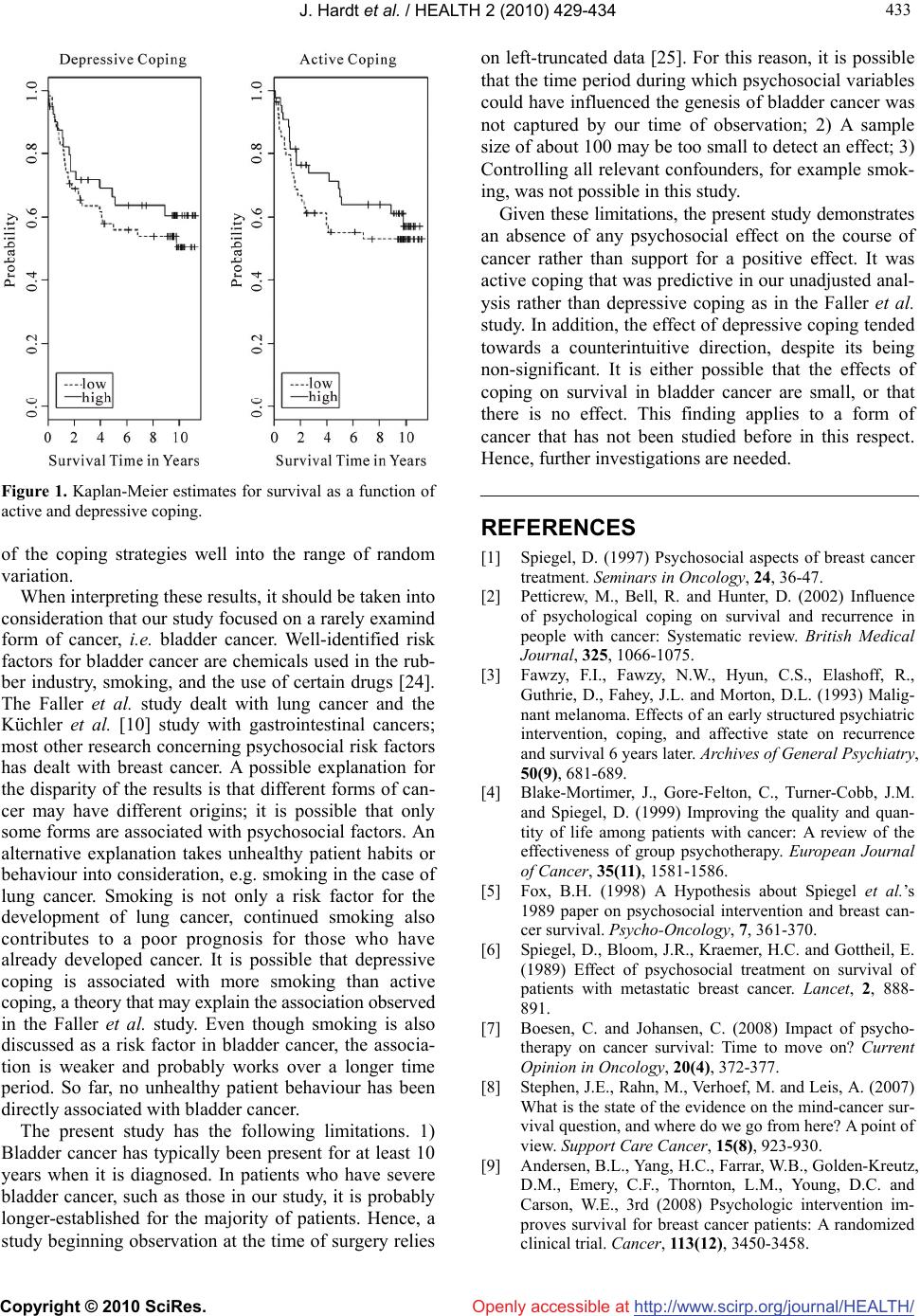

Vol.2, No.5, 429-434 (2010) doi:10.4236/health.2010.25064 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ Health Openly accessible at Coping styles as predictors of survival time in bladder cancer Jochen Hardt1*, Rolf Gillitzer2, Susanna Schneider1, Sabine Fischbeck1, Joachim W. Thüroff2 1Department of Medical Psychology and Medical Sociology, University of Mainz, Mainz, Germany; *Corresponding Author: jochen.hardt@gmx.de 2Clinic for Urology, University of Mainz, Mainz, Germany Received 2 December 2009; revised 8 January 2010; accepted 15 January 2010. ABSTRACT The role of coping in the survival of cancer is a controversial topic. To specifiy the influence of coping on survival time, we conducted a longi- tudinal, prospective and observational study. In a preoperative interview, 105 patients with pri- mary bladder cancer were asked about their active and depressive coping strategies. Ten years later, the survival rate was recorded; in cases of death, it was noted whether or not it was in consequence of the bladder cancer. Kaplan-Meier analyses of the collected data revealed a mean survival rate of about 60% after 10 years. Cox regression demonstrated no significant effect for active or depressive coping when tumour stage was controlled for. Patients who presented with high values for either of the coping strategies lived only slightly longer than those with low values. Therefore, it can be concluded that preoperative coping does not seem to demonstrate an important role for survival in bladder cancer. Keywords: Oncology; Coping; Bladder Cancer; Survival; Longitudinal Study 1. INTRODUCTION With respect to survival time of patients with cancer, the role of coping is a controversial topic. Early intervention studies provided some evidence that active coping and the development of a fighting spirit against the cancer were associated with longer survival times [1-3]. In these studies, a usually randomly selected portion of the patients received some sort of psychotherapy or psycho- social support, whereas patients in a control group did not. Typically, patients who were treated displayed longer survival times than controls [4]. These studies have been criticised as having flaws in design and anal- yses [5]. For example, in the study by Spiegel et al. [6], the control group showed an unusually strong decline in survival, i.e. an atypical form for a survival curve. The intervention group, however, displayed a rather normal survival curve, as would be expected for the given type of cancer. Furthermore, the sample sizes in these studies have been criticised as being small on average-often fewer than 40 subjects. In 2007, three replication studies of classical psychosocial interventions were published- none showing a positive effect on survival time [7]. Most of the survival studies were carried out on patients with breast cancer, therefore the results might not nece- ssarily be representative for other types of cancer. A recent review concluded: “Some researchers view the mind- cancer survival question as resolved and negative, wher- eas others identify conceptual and methodological chal- lenges and view the possible impact of psychosocial factors on survival as simply unproven” [8]. A study that bolstered the latter supposition demo- nstrated that giving psychosocial support did lead to prolonged survival [9] in breast cancer. Additionally, a further study proved that giving even very limited psy- chosocial support to patients with gastrointestinal cancer led to a doubled survival rate after 10 years when com- pared with controls without psychosocial support [10]. In general, observational studies have added to the controversy rather than confirming one specific theory. Similar to intervention studies, observational studies yielded some evidence for better survival in patients with active versus depressive coping, but also some evi- dence that psychosocial factors do not have an effect on survival rates [2]. These observational studies often suf- fered from the fact that many variables with a potential impact on the development of cancer were examined in small samples. For example, Gruhlke et al. [11] exam- ined a total of 34 coping strategies in a sample of about 60 patients who were receiving bone marrow transplants. In a design like this, there is an increased risk of finding significant predictors even if no associations are actually  J. Hardt et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 429-434 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/Openly accessible at 430 present. Another study found effects of traumatic stress experience on survival in breast cancer [12] in addition to effects of mature and immature defence styles in various patients with late-stage cancer [13]. Other results from observational studies appear to be sounder and could be replicated. In an early study, for example, slightly higher cancer rates in widowed people than in the rest of the population were reported [14]. This result was confirmed later, based on the Danish registries [15]. Faller et al. [16] demonstrated that depressive coping was associated with significantly shorter survival times in patients with lung cancer. In this study, various coping styles were measured in 107 patients before surgery; one of these styles proved to be associated with survival time assessed up to 10 years after surgery, i.e. depressive coping predicted shorter survival. The association remained significant even after controlling for cancer staging and the Karnofski performance status. Moreover, it was found that a majority of patients themselves believe that stress and emotional problems are associated with the development of cancer. Active coping did not predict a better survival, a result that was surprising because it was a main predictor in other studies [17]. Active and depressive coping differ on account of the fact that active coping focuses on finding solutions for the problems directly caused by the stressor itself whereas depressive coping concentrates on the negative emotions evoked by the stress. On the other hand, Ake- chi et al. [18] could not find any psychosocial predictor for survival time in patients with lung cancer. A study by Johansen et al. indicated that not even psychosocial dis- tress was associated with survival in various forms of cancer [19]. Based on the Danish health registries, the authors compared the national incidence rate of cancer with the incidence rate in over 10 000 parents who had experienced the diagnosis of cancer in their child. The rationale of this study was that such an experience con- stitutes an extraordinary stress factor for a parent, and if psychosocial stress were associated with cancer, this stress would produce some effects. On finding that both rates were the same over a period of 50 years for breast cancer, lymphoma, leukaemia and other tumours, the authors concluded that psychosocial stress does not play a role in the incidence of cancer. The present study was conducted to explore the role of coping in a rarely examined form of cancer, i.e. bladder cancer. The estimated yearly incidence rate of bladder cancer in Germany is about 40 per 100 000 in men and about 10 per 100 000 in women; in countries where schistosomiasis occurs, the rate is higher. At present, non-invasive forms of bladder cancer have been seen in about 80% of primary diagnoses and have usually been treated conservatively; invasive forms have affected about 15% of patients and lead to either bladder extraction, necessitating an artificial urinary diversion, or to radiation therapy. Even for invasive bladder cancer, the prognosis for patients is not bad. Leissner et al. [20] estimated 10-year survival rates of about 50% after radical surgery; for patients with low-stage tumours, survival rates were even better. 2. MATERIALS AND METHODS 2.1. Design The design of the study was prospective and observ- ational. In 1999, data collection for a one-year follow-up study about quality of life after urinary diversion was finished and data were analysed [21]. At that time, an article by Faller et al. [16] was published that showed differences in survival time of lung cancer patients depending on a preoperative coping strategy. Due to the fact that 1) the instrument used to assess self-rated cop- ing was the same in the Faller et al. study and in ours; 2) the times of assessments were similar; 3) various back- ground variables were assessed similarly; and 4) the sample sizes were almost identical, we decided to set up a 10-year follow-up of our sample in an attempt to cross-validate the results of Faller et al.. 2.2. Subjects Utilizing a consecutive recruitment strategy, we exa- mined a total of 108 patients who were treated in the urological clinic in Mainz between January 1996 and April 1998 because of a primary bladder tumour. The patients were examined one to three days preoperatively by means of an interview and a questionnaire booklet. At that time, patients believed that their bladder was going to be removed and replaced by an artificial urinary diversion. A total of 105 of the patients received an arti- ficial diversion, in three patients the bladder was retained. All patients gave written, informed consent to participate in a study about quality of life. They were informed that their participation in the study included their willingness to be contacted one year after surgery and asked to fill out another questionnaire about quality of life. Three patients withdrew their participation after surgery, and no further information was gathered about them. The remaining 105 patients were contacted one year after surgery; at this time, 81 patients reported about their quality of life. One year after surgery, patients showed a stronger decrease in physical than in mental quality of life; in addition, there were complex interactions be- tween coping and quality of life [21]. At that time, 19 patients were deceased; out of the remaining five, three felt too sick to fill out the questionnaire and two did not respond to our letters. For the 19 patients who were de- ceased, we recorded when they had died and whether or not death was a consequence of the bladder tumour. In cases of uncertainty regarding the latter point, a urologist  J. Hardt et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 429-434 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/Openly accessible at 431 431 was contacted to make a decision. In 2007, all 81 patients who had responded one year after surgery, in addition to the five surviving patients who had failed to respond, were contacted again via a letter reminding them about their stay at the urological department of the University of Mainz and their partici- pation in a study 10 years previously. The letter indi- cated that in the next few days they would receive a phone call query regarding their current quality of life. During the phone call, patients were first asked how they were coming along with their artificial urinary diversion; in case of problems, a visit to the urological department in Mainz was offered. For patients who were interested, an appointment with a urologist (RG) was set outside the regular patient schedule. Then, a quality of life ques- tionnaire was sent to the surviving patients. For deceased patients, relatives were asked about the time of death and whether the death was a consequence of the bladder tumour or of another disease or circumstance. Several measures were taken to collect information about those patients who could not be reached in this way. Local authorities were contacted to find out whether a patient had moved or died. Those who had moved were con- tacted again at their new address; for the deceased, the local registries of death were consulted to find out whether or not the death was due to the bladder tumour. When no data were available, patients’ family doctors, general practitioners, or local urologists were contacted. 2.3. Instruments Coping was assessed by the Freiburger Fragebogen zur Krankheitsverarbeitung [FKV-LIS SE: 22], a widely used questionnaire in Germany. The questionnaire con- tains 35 items and is designed to measure five dimen- sions: active coping (5 items), depressive coping (5 items), distraction (5 items), self-affirmation (5 items), and trivializing (3 items; the remaining 12 items were not utilzed). Since we were interested only in replicating the results of Faller et al. [16] and not in undertaking any exploratory analyses, we considered only two dimen- sions: active and depressive coping. Neither dimension represents the end of a continuum; rather, each reflects a distinctive dimension [22]. The reliabilities of the scales were moderate within the present sample, i.e. Cron- bach’s = 0.72 for active coping and = 0.69 for de- press- sive coping. The correlation between the two di- mensions was slightly positive, i.e. r = 0.27, p < 0.01. Examples of items for active coping were “gathering information about the disease and its treatment” and “deciding to actively fight the disease”. For depressive coping, examples were “self-pity” and “withdrawal from others”. A significant background variable that was con- sidered in the Faller et al. study was tumour stage; hence, we also included it in our analysis. Tumour stage and grade were coded according to the TNM classification. In addition, gender and age at surgery were included. 2.4. Statistics A few missing data were substituted by the mean or a value close to the mean (Table 1). This method has been proven to be superior to analysis of complete data in various simulation studies and a complex method of substituting missings such as multiple imputation did not seem justified given the small amount of missing data in the present sample. Bivariate associations were calcu- lated as Pearson correlation coefficients, except for sur- vival time. Because a substantial proportion of patients in this sample died from reasons other than bladder can- cer, multivariate as well as bivariate associations with survival time were calculated using Cox regressions, defining death from bladder cancer as the response. This procedure ensured that patients who were still alive and those who died due to disorders other than a bladder tumour were treated appropriately. Survival curves were presented by Kaplan-Meier estimates. Statistical analy- ses were performed by R [23]. 3. RESULTS Ten years after surgery, 41 patients were still alive; 46 were deceased due to the tumour progression and 17 patients had died from other diseases. Regarding the deceased patients, dates of death and information about the reasons for death were recorded for all 46 patients. Again, in cases of unclear information, a urologist (RG) was contacted to decide whether or not the death was tumour-related. Thus, a total of 105 patients (97% of the intended sample) were analysed. Additional relevant patient characteristics are summarised in Table 1. In the bivariate analysis, there was a significant effect of active coping (hazard ratio = 0.70, p < 0.05) on sur- vival in the assumed direction, depressive coping showed no significant effect (hazard ratio = 0.70, p < 0.14; Figure 1, Table 2). In the multivariate analyses, i.e. controlling for various confounders, tumour stage (haz- ard ratio = 1.51, p < 0.01) and age at surgery (hazard ratio = 1.04, p < 0.05) were the only significant predic- tors of survival time (Table 3). Active as well as de- pressive coping became non-significant. 4. DISCUSSION The present study was designed to replicate a finding of Faller et al. that depressive coping is associated with shorter survival time and active coping may be associ- ated with longer survival time in cancer patients. The hypothesis for this study was not formulated very spe- cifically because the Faller et al. study did not prove a significant effect for active coping. However, the hy- pothesis had to be rejected for both coping strategies. Controlling for confounders moved all effects for either  J. Hardt et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 429-434 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/Openly accessible at 432 Table 1. Description of variables. Variable possible range Valid N Min Max Mean Standard deviation Missings substituted by Y Survival time (years) 0-11 105 0.01 11.17 5.98 4.19 - A Active coping (FKV) 0-5 104 1.00 3.20 3.36 0.88 3.36 D Depressive coping ( FKV ) 0-5 104 1.00 5.00 1.82 0.64 1.82 S Tumour stage 0-4 101 0.00 4.00 2.15 1.23 2 G Tumour grade 0-4 105 0.00 4.00 2.36 1.07 2 E Age at surgery 18-90 105 41.77 82.53 64.42 8.93 - X Sex 105 0 female 1 male 75% male - - Table 2. Bivariate associations. Variable Survival time* Active Depressive Stage Grade Age Survival time Active coping 0.69 (0.12) p < 0.035 Depressive coping 0.70 (0.17) p < 0.136 0.27 0.005 Tumour stage 1.52 (0.20) p < 0.002 –0.30 0.002 –0.16 0.096 Tumour grade 1.07 (0.15) p < 0.647 –0.02 0.814 0.03 0.760 0.44 0.000 Age at surgery 1.04 (0.22) p < 0.029 –0.16 0.106 –0.37 0.000 0.03 0.729 –0.03 0.783 Sex 1.50 (0.56) p < 0.274 0.07 0.474 –0.11 0.281 –0.05 0.579 0.07 0.472 0.34 0.000 * Hazard ratio (std err), all others Pearson correlations and p-values. Table 3. Prediction of survival time. Response variable: Y, survival time Starting model Selected model Excluded variables Explanatory variable Estim. coeff. Stand. error z-value Estim. coeff.Stand. errorz-value z-value Active coping –0.18 0.20 0.93 –0.27 0.10 –2.67 - Depressive coping 0.01 0.27 0.05 - - - Tumour stage 0.41 0.15 2.70 0.41 0.13 3.07 Tumour grade –0.11 0.17 –0.63 - - - Age 0.03 0.02 1.62 0.04 0.02 2.09 Sex 0.25 0.40 0.63 - - - Total model Chi² (2) = 14.12, p < 0.001  J. Hardt et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 429-434 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 433 433 Openly accessible at Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier estimates for survival as a function of active and depressive coping. of the coping strategies well into the range of random variation. When interpreting these results, it should be taken into consideration that our study focused on a rarely examind form of cancer, i.e. bladder cancer. Well-identified risk factors for bladder cancer are chemicals used in the rub- ber industry, smoking, and the use of certain drugs [24]. The Faller et al. study dealt with lung cancer and the Küchler et al. [10] study with gastrointestinal cancers; most other research concerning psychosocial risk factors has dealt with breast cancer. A possible explanation for the disparity of the results is that different forms of can- cer may have different origins; it is possible that only some forms are associated with psychosocial factors. An alternative explanation takes unhealthy patient habits or behaviour into consideration, e.g. smoking in the case of lung cancer. Smoking is not only a risk factor for the development of lung cancer, continued smoking also contributes to a poor prognosis for those who have already developed cancer. It is possible that depressive coping is associated with more smoking than active coping, a theory that may explain the association observed in the Faller et al. study. Even though smoking is also discussed as a risk factor in bladder cancer, the associa- tion is weaker and probably works over a longer time period. So far, no unhealthy patient behaviour has been directly associated with bladder cancer. The present study has the following limitations. 1) Bladder cancer has typically been present for at least 10 years when it is diagnosed. In patients who have severe bladder cancer, such as those in our study, it is probably longer-established for the majority of patients. Hence, a study beginning observation at the time of surgery relies on left-truncated data [25]. For this reason, it is possible that the time period during which psychosocial variables could have influenced the genesis of bladder cancer was not captured by our time of observation; 2) A sample size of about 100 may be too small to detect an effect; 3) Controlling all relevant confounders, for example smok- ing, was not possible in this study. Given these limitations, the present study demonstrates an absence of any psychosocial effect on the course of cancer rather than support for a positive effect. It was active coping that was predictive in our unadjusted anal- ysis rather than depressive coping as in the Faller et al. study. In addition, the effect of depressive coping tended towards a counterintuitive direction, despite its being non-significant. It is either possible that the effects of coping on survival in bladder cancer are small, or that there is no effect. This finding applies to a form of cancer that has not been studied before in this respect. Hence, further investigations are needed. REFERENCES [1] Spiegel, D. (1997) Psychosocial aspects of breast cancer treatment. Seminars in Oncology, 24, 36-47. [2] Petticrew, M., Bell, R. and Hunter, D. (2002) Influence of psychological coping on survival and recurrence in people with cancer: Systematic review. British Medical Journal, 325, 1066-1075. [3] Fawzy, F.I., Fawzy, N.W., Hyun, C.S., Elashoff, R., Guthrie, D., Fahey, J.L. and Morton, D.L. (1993) Malig- nant melanoma. Effects of an early structured psychiatric intervention, coping, and affective state on recurrence and survival 6 years later. Archives of General Psychiatry, 50(9), 681-689. [4] Blake-Mortimer, J., Gore-Felton, C., Turner-Cobb, J.M. and Spiegel, D. (1999) Improving the quality and quan- tity of life among patients with cancer: A review of the effectiveness of group psychotherapy. European Journal of Cancer, 35(11), 1581-1586. [5] Fox, B.H. (1998) A Hypothesis about Spiegel et al.’s 1989 paper on psychosocial intervention and breast can- cer survival. Psycho-Oncology, 7, 361-370. [6] Spiegel, D., Bloom, J.R., Kraemer, H.C. and Gottheil, E. (1989) Effect of psychosocial treatment on survival of patients with metastatic breast cancer. Lancet, 2, 888- 891. [7] Boesen, C. and Johansen, C. (2008) Impact of psycho- therapy on cancer survival: Time to move on? Current Opinion in Oncology, 20(4), 372-377. [8] Stephen, J.E., Rahn, M., Verhoef, M. and Leis, A. (2007) What is the state of the evidence on the mind-cancer sur- vival question, and where do we go from here? A point of view. Support Care Cancer, 15(8), 923-930. [9] Andersen, B.L., Yang, H.C., Farrar, W.B., Golden-Kreutz, D.M., Emery, C.F., Thornton, L.M., Young, D.C. and Carson, W.E., 3rd (2008) Psychologic intervention im- proves survival for breast cancer patients: A randomized clinical trial. Cancer, 113(12), 3450-3458.  J. Hardt et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 429-434 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/Openly accessible at 434 [10] Kuchler, T., Bestmann, B., Rappat, S., Henne-Bruns, D. and Wood-Dauphinee, S. (2007) Impact of psychothera- peutic support for patients with gastrointestinal cancer undergoing surgery: 10-year survival results of a ran- domized trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 25, 2702- 2708. [11] Grulke, N., Bailer, H., Hertenstein, B., Kachele, H., Ar- nold, R., Tschuschke, V. and Heimpel, H. (2005) Coping and survival in patients with leukemia undergoing al- logeneic bone marrow transplantation—long-term fol- low-up of a prospective study. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 59(5), 337-346. [12] Palesh, O., Butler, L.D., Koopman, C., Giese-Davis, J., Carlson, R. and Spiegel, D. (2007) Stress history and breast cancer recurrence. Journal of Psychosomatic Re- search, 63(3), 233-239. [13] Beresford, T.P., Alfers, J., Mangum, L., Clapp, L. and Martin, B. (2006) Cancer survival probability as a func- tion of ego defense (adaptive) mechanisms versus de- pressive symptoms. Psychosomatics, 47, 247-253. [14] Jones, D., Goldblatt, P.O. and Leon, D.A. (1984) Be- reavement and cancer: Some results using data on deaths of spouses from the OPCD longitudinal study. British Medical Journal, 284, 461-464. [15] Johansen, C., Schou, G., Soll-Johanning, H., Mellem- gaard, A. and Lynge, E. (1998) Marital status and sur- vival in colorectal cancer. Ugeskr Laeger, 160(5), 635- 638. [16] Faller, H., Bülzebruck, H., Drings, P. and Lang, H. (1999) Coping, distress, and survival among patients with lung cancer. Archives of General Psychiatry, 56, 756-762. [17] Riehl-Emde, A., Buddeberg, C., Muthny, F.A., Landolt- Ritter, C., Steiner, R. and Richter, D. (1989) Causal attri- buation and coping with the disease in breast cancer pa- tients. Psychother Psychological Medicine, 39, 232-238. [18] Akechi, T., Okamura, H., Okuyama, T., Furukawa, T.A., Nishiwaki, Y. and Uchitomi, Y. (2009) Psychosocial fac- tors and survival after diagnosis of inoperable non-small cell lung cancer. Psychooncology, 18(1), 23-29. [19] Johansen, C. and Olsen, J.H. (1997) Psychosocial stress, cancer incidence and mortality from non-malignant dis- eases. British Journal of Cancer, 75(1), 144-148. [20] Leissner, J., Hohenfellner, R., Thüroff, J.W. and Wolf, H.K. (2000) Lymphadenektomie in patients with transi- tional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder: Significance for staging and prognosis. BMU Int, 85, 817-823. [21] Hardt, J., Petrak, F., Filipas, D. and Egle, U.T. (2004) Adaptation to life after surgical removal of the bladder— an application of Graphical Markov Models for analysing longitudinal data. Statistics in Medicine, 23, 649-666. [22] Muthny, F.A. and Koch, U. (1998) Spezifität der Krank- heitsverarbeitung bei Krebs. In: Koch, U. and Weis, J., Eds., Krankheitsbewältigung bei Krebs und Möglich- keiten der Unterstützung, Stuttgart, Schattauer, 49-58. [23] R Development Core Team: R: A language and environ- ment for statistical computing. Vienna, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2007. [24] Golka, K., Goebell, P.J. and Rettenmeier, A.W. (2007) Ätiologie und Prävention des Harnblasenkarzinoms. Deutsches Ärzteblatt, 104, 719-723. [25] Wolfson, C., Wolfson, D.B., Ashgarian, M., M'lan, C.E., Ostby, T., Rockwood, K. and Hogan, D.B. (2001) A re- evaluation of the duration of survival after the onset of dementia. New England Journal of Medicine, 344(15), 1111-1116. |