Vol.2, No.5, 418-428 (2010) doi:10.4236/health.2010.25063 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ Health Openly accessible at Mapping out the social experience of cancer patients with facial disfigurement Alessandro Bonanno*, Jin Young Choi Department of Sociology Sam Houston State University, Huntsville, USA; *Corresponding Author: SOC_AAB@SHSU.EDU Received 25 November 2009; revised 14 January 2010; accepted 16 January 2010. ABSTRACT This article contributes to the limited literature on the social consequences of cancer gener- ated facial disfigurement by reporting the result of an exploratory analysis of interaction be- tween facially disfigured cancer patients and strangers and acquaintances (secondary groups). Secondary groups are those in which member- ship occurs due to performance of formal and/or non-intimate roles. Interaction is studied as it takes place in different social settings. Indivi- duals who are affected by cancer of the head and neck region can now expect to survive for many years after the cancer is detected and later surgically removed. Because of surgery, these survivors live the rest of their lives with facial disfigurement and are stigmatized and socially excluded. It follows that a new and so- cially relevant situation has emerged: as medi- cine develops and allows more patients to sur- vive, it forces them to spend significant portions of their lives dealing with the stigma associated with facial disfigurement. Research on social issues pertaining to facially disfigured cancer patients remains sparse. Limited knowledge has been produced on the “social context” within which interaction between the disfigured and relevant social groups takes place. To date most research has focused on the individual and his/her ability to adapt to the condition of fa- cially disfigured. To address this scientific gap and document the manner through which the interaction process is socially created and evolves, interviews with fourteen facially dis- figured cancer patients were carried out. These interviews were designed to reconstruct the interaction experiences of these individuals in different social contexts. Data were analyzed through the qualitative approach of grounded theory. Results indicate that patients can be di- vided into two groups: Occasionally Comfort- able Patients and Always Comfortable Patients. Occasionally comfortable patients are individu- als who experience different levels of comfort in interaction. In some situations they do not feel stigmatized, but other interactions constitute the contexts within which this discomfort emerges. Discomfort in interaction was employed as an indicator of stigmatization. Interacting groups were divided into small and large. Intrusion (unsolicited attention to patients) in interaction in large and small groups always generates uncomfortable situations. Sympathy (unsolic- ited comments and/or actions in support of pa- tients) is associated with comfort in interaction in small groups and produces varying patterns in the case of large groups. Benign neglect (a situation in which interacting individuals do not pay particular attention to patients) produces comfort in interaction within large groups and varying outcomes in the case of small groups. Always comfortable patients are those who do not experience discomfort in interaction regard- less of the size and characteristics of the inter- acting group. The article concludes by stressing that facially disfigured cancer patients should be prepared to face different interaction pat- terns. Simultaneously, efforts should be made to educate patients and the general public about these interaction patterns. Keywords: Facial Disfigurement; Cancer; Stigma; Social Interaction 1. INTRODUCTION The objective of this article is to illustrate the results of an exploratory analysis on the patterns of social interac- tion experienced by individuals who are facially disfig- ured because of cancer. Individuals who are affected by cancer can expect to be cured and/or survive for a num- ber of years after the cancer is detected and later surgi- cally removed [1,2]. This is also the case of patients with head and neck cancer who remained facially disfigured  A. Bonanno et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 418-428 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/Openly accessible at 419 419 because of it [3,4]. In this particular instance, surgical intervention signifies the removal of portions of the face that are affected by the malignancy. Additional conse- quences are possible and they often include the collapse of parts of the face that may not be directly touched by surgical intervention [5]. Accordingly, patients’ facial disfigurement may involve a larger portion of the face than that originally affected by cancer [6]. Surgical pro- cedures to correct these alterations are common along with the availability of increasingly sophisticated pros- theses [3]. Yet, results often do not rectify notable dif- ferences from the “normal” face. Accordingly survivors typically live the rest of their lives with major alterations of their normal facial appearance. In contemporary society, the face represents one of the most notable items employed to determine identity and participate in social interaction [7-9]. It is a central ele- ment of communication [10,11], an item employed to attribute both “normality” and ownership of socially desirable characteristics [12-16] and a feature that de- fines interaction as individuals endowed with a pleasant face are better treated than other and less attractive members of society [17,18]. Owing to the social impor- tance of the face, facially disfigured individuals are stigmatized and experience difficulties when interacting with other segments of society [11,12,14-16,19-21]. It follows that a new and socially relevant situation has emerged. As medicine develops and allows more pa- tients to survive, it also makes them spend significant portions of their lives dealing with the stigma associated with facial disfigurement. Research on social issues pertaining to facially disfig- ured cancer patients remains sparse and attracts even less attention than the already limited research associated with other forms of acquired and congenital disfigure- ment [10,15,22-24]. Additionally, analytical problems have limited the accuracy of available research results [25]. In this context, limited knowledge has been pro- duced on the “social context” within which interaction between the disfigured and relevant social groups takes place [21,25]. Throught this paper we would like to con- tribute to this limited literature. In particular, this article offers the results on an exploratory analysis on patterns of interaction between disfigured patients and members of secondary groups (acquaintances and strangers) as interaction occurs in different social settings. Interaction with other groups, such as family members and friends (primary groups), is important. However, in this work we focus exclusively on interaction between patients and members of secondary groups. The study of the interac- tion with other groups remains a relevant topic to be further explored. Methodologically, the study consists of in-depth inter- views with fourteen cancer patients who underwent sur- gery to treat head and neck cancer and remained facially disfigured because of it. Patients were enrolled following a protocol that excluded minors and those who could not express themselves in English. Given the relative limited size of this patient population, the adoption of a qualita- tive approach was recommended. A semi-structured questionnaire was employed and data were analyzed employing Grounded Theory [26]. Grounded theory is a technique of qualitative data analysis that allows the identification of patterns directly from the data. Rather than hypothesis verification (pre-existing ideas to be verified in reality), grounded theory allows the devel- opment of categories (variables) and their relationships (patterns) that are not established a priori. These catego- ries and patterns emerge directly from the data and can be always traced back to the data themselves. Because there are no pre-conceived hypotheses to be tested, this technique is particularly appropriate for exploratory analyses [26]. This is a qualitative study as it is aimed at illustrating the manner though which the patterns of in- teraction unfold. It explains the “how” these patterns manifest themselves and develop rather than how often they occur in reality. It also stresses the process through which the interaction is created and grows rather than its outcomes. Given the small size of the sample, this ap- proach has been considered more appropriate than quan- titative statistical analysis. The statements concerning the result have been veri- fied through established data verification techniques. In particular the techniques of “saturation” and “negative cases” were employed. In the case of saturation, the creation of categories is verified by searching for possi- ble instances in which data cannot be explained by the category in question. When no more instances to be ex- plained by the category in question are found in the data, the category is said to be saturated and therefore verified. In the instance of negative cases, categories are com- pared with situations in which their attributes are contra- dicted by evidence. As categories that have negative cases are eliminated, the remaining ones are considered verified. These techniques were applied to the construc- tion of the categories and patterns employed in this arti- cle. The objective of the article is to identify patterns of interaction between facially disfigured individuals and members of secondary groups. Secondary groups were defined as non-intimate, formal groups consisting of acquaintance and strangers. Results indicate that facial disfigured patients feel stigmatized when interacting within small and large groups and the interacting coun- terpart(s) shows “intrusion” (i.e., unrequested attention to patients including unwanted questions, remarks and stares). Patients respond in varying manner when “sym- pathy” (i.e., unsolicited comments and/or actions show- ing support) and “benign neglect” (i.e., no particular attention paid to patients) characterized the interaction. A group of patients that do not feel stigmatized during various types of interaction was indentified. The paper  A. Bonanno et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 418-428 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 420 Openly accessible at concludes by stressing the importance of studying stig- matization through a sociological approach and by pointing out that cancer survivors and the general public alike could benefit from education about these interac- tion outcomes. 2. CANCER AND FACIAL DISFIGUREMENT: SALIENT LITERATURE Stigma is a mark of disgrace attached to people who are considered different. As indicated by Goffman [13], dif- ference is socially constructed and is the outcome of discrepancies between an individual virtual social iden- tity (expectations about what that individual ought to be) and his/her actual social identity (the attributes he/she actually posses) [13]. When the actual social identity is perceived as departing from normality, the individual is “reduced in our minds from a whole and usual person to a tainted, discounted one. “Such an attribute is a stigma” [13]. Stigma is attached to an individual’s feature “that is deeply discrediting” and that separates that person from the group of the normals. However, its actual genesis should not be linked to attributes but, rather, to the in- teraction between the stigmatized person and other members of society. “A language of relationships, not attributes, is really needed” Goffman states [13]. Stigma is generated by the existence of a number of blemishes. There are those of individual character such as homo- sexuality, dishonesty, imprisonment, radical political behavior, and addiction. There are those of tribal stigma that are related to a person’s religion, ethnicity or race. And there are those of “abominations of the body” that refer to physical abnormalities. Goffman includes facial disfigurement in this category [13]. Following the seminal work of Erving Goffman [13], social stigma has been widely studied and this produc- tion includes works such as those on stigma generated from diseases (i.e., cancer and AIDS) [27], physical dis- abilities [28,29], and mental health1 [30,31]. In spite of this wealth of contributions, the stigma caused by facial disfigurement has been the subject of only a relatively small number of works [10,15,21,22, 24,32]. These analyses stressed the social importance of the face and the problems that affect those who display visible facial blemishes [12-16]. In a society in which individuals are fully clothed for virtually all of their so- cial activities, the face represents one of the most notable physical attributes and a significant source of social in- formation prior to, and during, social interaction [8,9, 30,33]. Accordingly, people possessing an attractive face2 are not only considered physically pleasing3, but they are often viewed as endowed with intellectual and emotional characteristics that are unrelated to their physical appearance [10,11,36]. Intelligence, kindness, likableness, and high morality are frequently associated with an attractive appearance. Unsurprisingly, these in- dividuals are also better treated by others than less at- tractive members of society [17,18]. Lacking some of these physical attributes, facially disfigured individuals commonly engender negative responses by other mem- bers of society. Stigmatized and socially excluded, their ability to interact is often distorted and interaction is the source of problems including verbal and physical abuse, ridicule, hostile behavior, and isolation [10,12,37]. The literature identifies two types of facial disfigure- ment: congenital and acquired. Acquired disfigurement received less scientific attention than the already limited literature on congenital disfigurement [24]. Acquired disfigurement is further divided into trauma- and can- cer-generated disfigurement. Research demonstrates that individuals with acquired facial disfigurement suffer psycho-social consequences that are different and, at least to some degree, more pronounced than those ex- perienced by individuals with congenital disfigurement [18,24]. Among individuals with acquire facial disfig- urement, cancer patients4 experience less social and psychological problems than individuals who have been disfigured because of trauma [38]. However, cancer pa- tients’ “fear of dying is immense” [39]. And this situa- tion affects these individuals and their family members’ perception of disfigurement [40]. In this context, patients are more preoccupied with the evolution of their cancer than with the social consequences of the scars that the disease left on their faces [24,40]. As this fear of dying diminishes, however, the process of dealing with the deformity affects both patients and family members 2Early research on physical appearance paid more attention to the face than the rest of the body. It was stressed that the face was the most visible part of the body, its stability of appearance was grater than body appearance both in terms of the individual’s lifespan and devel- opmental stages, and physical attractiveness was predominantly deter- mined by the face. Recent research, however, while still emphasizing the face [4], has underscored the growing importance of the body in the determination of beauty and attractiveness [9,20]. 3“…Beauty is perceived as residing principally in the face.” [33]. 4While the social perception of cancer has changed in recent decades, this disease engenders a wide variety of attitudes and responses tha differentiate it from other pathological situations [46]. Often, these attitudes and responses are stigmatizing [47,48]. However, differences have been recorded between reactions to forms of cancer that are per- ceived as “uncontrollable”—such as breast cancer – and those that are erceived as “controllable”—such as lung cancer due to smoking. Because the latter are seen as deriving from the patient’s voluntary actions, more stigmatizing reactions are expected [49]. 1This abundant literature has also underscored important limits of the use of the concept of stigma. For instance, stigma has been studied with a strong individualistic focus, it is often employed by people who do not belong to stigmatized groups, there is no consensus on a com- mon definition, and the existence of these multiple definitions allow the charge that this concept is too inclusive to be actually informative ([28] Cahill and Eggleston, 1995:682; [34] Link and Phelan, 2001: 365-366). There are also uncertainties about its manifestations as “felt” stigma—the individual’s “shame” associated with the blemish—is much more common than the rare “enacted” stigma—or the existence of overt episodes of discrimination ([35] Jacobi, 1994:269).  A. Bonanno et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 418-428 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/Openly accessible at 421 421 [39,40]. The association of cancer and disfigurement is persistent. In effect, therapy almost inevitably mandates surgical removal of cancer-affected parts of the face making it an undesirable consequence of successful medical intervention [20,41,42]. Among the limits of this otherwise important litera- ture is the lack of attention paid to the social context within which the consequences of facially disfigurement emerge [12,21,25,32]. Emphasis is placed on the indi- vidual, his/her characteristics, and efforts to adapt to his/her condition of disfigured [4,39]. This posture downplays “the everyday experience of the disfigured population in social settings” [17,21,25,32,37,43]. In this context, the “interaction process” through which disfig- urement is experienced is viewed almost exclusively in terms of the significance of individual behavior as a pre- dictor of social outcomes [19,32,43]. This is also the case when other social actors—such as partners—are studied [37,44]. In particular, limited attention is paid to the fact that disfigurement is socially constructed and generated through processes of interaction that involve multiple actors and take different forms according to the settings in which they unfold [21]. The individual remains the research focus also in studies on the relationship between cancer-generated facial disfigurement and stigmatization [45]. Indeed, research on stigma has been “decidedly individualistic in focus” [34]. Accordingly, the ways in which interaction between the facially disfigured and the “normals” un- folds in different realms of society has been understud- ied. As Thompson and Kent put it “Most studies have examined the ‘view form the inside,” with little work [carried out] on the social and the ‘view form the out- side’” [25]. In this literature, the interaction of disfigured indi- viduals within primary groups has been privileged over than within secondary groups [15,16,45]. In particular, the spheres of the “family” and “caregivers” are por- trayed as social settings in which the disfigured find more comfortable terms of interaction. The family is seen both as a “safer place” in which the disfigured feel protected and supported and the institution that provides them with alternative messages than the stigmatizing ones coming from society and its strangers [15,16]. In- teraction with caregivers, and in particular those between surgeon, social workers and disfigured patients, is also viewed as comfortable [15]. To be sure, race-, ethnicity-, and culture-based forms of discrimination in the hospital are documented [16] and improvement in the manner in which health care professionals deal with those who are facially disfigured is frequently indentified as a primary programmatic objective. Nevertheless, the hospital is often identified as one of the settings in which patients achieve comfort in interaction [15]. The same literature indentifies secondary groups in terms of “strangers” who populate “public places” where they not only intrude into the lives of the facially de- formed through “staring, remarks, and questions, or ob- vious eye avoidance [16], but also negate that “civil in- attention” normally granted to other members of society [16]. These groups constitute the “popular mind” [16] that produces “generalized prejudice” [16]. The social settings where secondary groups exist are seen as gener- ating stigmatization as people deal “differently with those who have undergone facial surgery” [15] and en- gender “fear” to the disfigured [15]. Ultimately, society is the source of generalized stigmatization through widespread stereotyping that allows the “…unsightly face [to be] utilized as a visible symbol or a personifica- tion of evil, disease, criminality, or mental deficiency” [16]. This process of stigmatization is so pervasive that it is viewed as if it is conducted uniformly throughout so- ciety regardless of actors and settings [15,16]. While evidence indicates that society is the primary source of stigmatization [10,20,24,37,39], the manner thought which facially deformed cancer patients experience stigmatization in different spheres of society is under- studied [45]. van Doorne and his associates [39], share the view that members of the immediate family provide strong support to cancer patients who are facially disfig- ured. They also stress that strangers are consistently the source of stigmatization. In their view, further investiga- tion is needed to ascertain the manner in which non- immediate family members and acquaintances react to facially disfigured patients. In essence, the study of stigmatization of the facially disfigured is couched in approaches that stress the ac- tions and adaptability of the individual, on the one hand, and the homogenous dimension through which stigmati- zation is created in society, on the other. In this context, the manner in which facially disfigured cancer patients experience stigmatization while interacting with secon- dary groups in different spheres of society has not been adequately explored. This literature does not differenti- ate between the many settings that form the sphere of society and that are the contexts in which interaction with secondary groups takes place [45]. Owing this gap in the literature, the objective of this paper is to provide an exploratory analysis of the patterns of social interac- tion experienced by individuals who are facially disfig- ured because of cancer as they interact with members of secondary groups. 3. METHODS This exploratory research employed in-depth interviews with fourteen individuals who were facially disfigured because of head and neck cancer. A purposive sample was selected from a list of patients who were registered at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas. This  A. Bonanno et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 418-428 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/Openly accessible at 422 particular group of patients had cancer of the upper face area and specifically orbital and periorbital cancer. Po- tential participants were identified following the re- cruitment guidelines. They were adult patients (18 years old and older), who were diagnosed with various forms of head and neck cancer, underwent facial surgery to remove the malignancy and, in the process, acquired observable changes in their facial appearance. Addition- ally, they were required to be able to communicate in a meaningful manner with investigators. In-depth individual interviews were conducted by phone between January 2008 and April 2009. Twenty potential participants were contacted. Three of them could not participate for scheduling problems and three refused to be part of the project. Finally, a total of eight men and six women were interviewed. The median age of these patients was 66 years and the youngest patient was 31 and the oldest 81. At the time of the interview, the post-surgical period ranged from ten months to thirty five years and the median was five years. Some patients underwent additional reconstructive and plastic surgical procedures. While the extent of disfigurement varied, all of the patients were left with significant alterations in their facial appearance. A semi-structured questionnaire was employed. Ques- tions covered topics such as the individual’s demo- graphic and socio-economic characteristics; experience with cancer and treatment; perceived attitudes and ac- tions of others; and interaction in various events and places. Patients were interviewed by a single research team member. This procedure was adopted to assure consistency in the interview procedure. With the pa- tient’s consent, interviews were audio recorded and written notes were also taken. The transcribed texts were analyzed through grounded theory methodology [26,50]. This methodology permits the identification of conceptual categories and patterns among them from the text. Categories and patterns were verified through the techniques of “saturation” and “neg- ative cases.” Secondary groups were defined as noninti- mate, formal groups formed by strangers and acquaint- ances. Following data analysis, salient interaction pat- terns were identified and patients were divided into those feeling comfortable, uncomfortable or having varied or mixed feelings. The feeling of uncomfortable was con- sidered an indicator of the patient being stigmatized ei- ther in terms of felt stigmatization or enacted stigmatiza- tion. Felt stigmatization refers to the perception of the patient. Enacted stigmatization refers to overt actions of stigmatization. Interaction patters were identified and divided into three categories. Intrusion indicates that people pay unsolicited attention to patients, ask un- wanted questions, make unwelcome remarks and stare. It also indicates that they make their unspoken curiosity felt. Sympathy refers to unsolicited comments and/or actions showing support to patients and the desire to be of assistance. Benign neglect denotes a situation in which interacting individuals did not pay particular at- tention to patients. Size of interacting group was divided into small and large. These concepts indicate that the secondary group in which interaction took place was either large or small. The actual size of the group was determined through patients’ own descriptions of the settings. 4. FINDINGS Following grounded theory analysis of the data, two groups of patients were identified: Occasionally Com- fortable Patients (N = 10) and Always Comfortable Pa- tients (N = 4). Patterns of interaction with Occasionally Comfortable Patients are visually synthesized in Figure 1 and basic descriptive statistics for this group are pre- sented in Table 1. Basic descriptive statistics for Always Comfortable Patients are summarized in Table 2. Over 71 percent of the patients studies suffer from some forms of stigmatization. In relative terms, men suffer from stigmatization slightly more than women (75% versus 66.7%). Yet, women over 55 years of age experience stigmatization in slightly higher terms that men of the same age group. Intrusion is the source of stigmatization for the majority of patients and impacts men and women equally. Older men experience stigma- tization from sympathy more than women of the same Size of Group Small Large Intrusion Uncomfortable Uncomfortable Sympathy Comfortable Comfortable Uncomfortable Types of Interaction Postures Benign Neglect Comfortable Uncomfortable Comfortable Figure 1. Patient-secondary group interaction by size of group  A. Bonanno et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 418-428 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/Openly accessible at 423 423 and types of responses to disfigurement for Occasionally Comfortable Patients. Table 1. Basic characteristics and patterns of interaction of Occasionally Comfortable Patients, N = 10 (total patients studied N = 14). Gender Men 6 75% Women 4 66.7% Total 10 71.4% Age and Gender Men > 55 4 66.7% Men < 55 2 33.3% Women > 55 3 75% Women < 55 1 25% Total 7 70% Total 3 30% Intrusion 3 50% Men > 55 2 66.7 % Men < 55 1 33.3 % 2 50% Women > 55 2 100% Women < 55 0 0% 5 50% Sympathy 2 33.3% Men > 55 1 50% Men < 55 1 50% 1 25% Women > 55 0 0% Women < 55 1 100% 3 30% Benign Ne- glect 1 16.7% Men > 55 1 100% Men < 55 0 1 25% Women > 55 1 100% Women < 55 0 2 20% Table 2. Basic characteristics of Always Comfortable Patients, N = 4 (total patients studied N = 14). Gender Men 2 25% Women 2 33.3% Total 4 28.6% Age and Gender Men > 55 2 100% Women > 55 2 100% Total 4 100% age group while older women experience benign neglect relatively more than men. Due to the limited size of the sample and the qualitative design, these statistics are reported only as an illustration of possible quantitative trends. More pertinent findings are presented below in the discussion of the qualitative analysis. 4.1. Occasionally Comfortable Patients Occasionally comfortable patients are individuals who experience different levels of comfort in interaction. In some situations they do not feel stigmatized, but other interactions constitute the contexts within which this discomfort emerges. Intrusion in interaction in large and small groups always generates uncomfortable outcomes. Here patients are stigmatized. Sympathy is associated with comfort in interaction in small groups and produces varying patterns in the case of large groups. Benign ne- glect produces comfort in interaction within large groups and varying patterns in the case of small groups. 4.1.1. Intrusion This is a situation in which patients feel uncomfortable interacting within small and large groups alike. Members of interacting groups grant disfigured individuals the particular status of “different” and proceed to construct an interaction in which this condition is reinforced. Pa- tients are noted because their different appearance. They are drawn in interaction patterns in which their status of different is constructed and reinforced through unwanted attention. People’s questions, stares, remarks constitute elements that build a view of disfigurement that is stig- matizing. While varying, patients’ responses are charac- terized by dissatisfaction with the interaction. Interaction in large and small groups alike provides the terrain for the development of this constructed stigmatization. 4.1.1.1. Small Groups Joy provides an account of this type of interaction with small groups. She says: “Sometimes I notice that people…can tell that this side of my face does not make the same movements [than the other side]. They are probably aware that there is something strange about that woman…The first time that I took my six year old to dancing—my six year old granddaughter, she dances every Wednesday and then she is at church afterwards. The children have special things going on after dancing at the church… My daughter works a lot and so that Wednesday is mine. I take them and do all of that kind of thing. Well, the first few times when I was taking her to dancing, I sit and wait… can’t go off and leave her, wait in the room with the other parents and I could tell that some of the moth- ers were looking at me strangely, not in a mean way or anything like that but more curious, like there’s some- thing strange about that woman. What could it be? And generally, I have found that if I feel like somebody is making me feel uncomfortable… I’ll go ahead and say something.” She adds: “I went to a wedding shower for one of my daughter’s friends who I didn’t know very well and there were a lot of young women there that I did not know well… and I was uncomfortable there. I felt like the majority of them probably did not know that I had this problem [cancer generated facial disfigurement] and I’m sure they were wondering… that was an uncomfortable day…. I didn’t  A. Bonanno et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 418-428 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 424 Openly accessible at really enjoy that.” 4.1.1.2. Large Groups Arthur provides an instance of the interaction between patients and large secondary group. He says: “I feel like everybody’s always staring at me. It is strangers. [I have negative feelings] when dealing with strangers. Probably the worse is in restaurants. Because you are sitting there for a long time and the people around you are all eventually looking at you or you feel they are. [It is also the same] when you walk past some- body in a store or on the street or something… They stare at you… It is very crude and insensitive and it makes me skittish towards other people… it makes me feel very uncomfortable…I don’t go out very much anymore.” Janet adds: “When people keep staring at me and pretend they are not looking at me… It bothers me. Most adults—they will look at me. They all notice, I’m sure. A lot of them try to pretend… But it happens everywhere. The worst is at places like Super Centers. That where I found that people are most rude. It also bothers me that people let their kids be so rude, particularly big kids…. They run around you in front of me and go ‘she doesn’t have and eye! Look, look!’ Then I want to smack them. I want to tell them ‘you are very, very rude.’” 4.1.2. Sympathy Sympathy creates interaction patterns that are dissimilar for small and large groups. In small groups, data reveal that sympathy engenders comfortable interaction be- tween disfigured patients and acquaintances. The latter’s statements and actions are intended and perceived as supportive and contribute to the construction of a situa- tion in which disfigured patients find themselves at ease. The analysis indicates that varying patterns define the interaction between patient and members of large groups. Sympathy shapes positive interaction as people’s support is employed to construct advantageous conditions for patients. Instrumentally, patients use this support even in situations in which it is not needed. Simultaneously, pa- tients also feel uncomfortable when sympathy transcends the necessary. They feel that they their disfigurement is constructed as a grater disadvantage than it actually is and/or a situation that creates undeserved respect. In this instance, overt sympathy becomes a negative factor in the construction of interaction. It is important to note that sympathy is also associated with the existence of cancer. In some instances, interacting individuals display sympathy to patient primarily because of their status of survivors. 4.1.2.1. Small Group Lisa provides evidence of a positive interaction with small groups. She says: “Nobody tells me anything. The only thing is they ask me what happened, you know, what is wrong. That’s the question. Then I have to tell them that I had surgery and I had cancer and I had a tumor… This is friends, friends that I haven’t seen in a long time and I happen to meet in a store while I’m shopping, people that I haven’t seen in a long time… they will ask questions… and when I ex- plain to them what happened everybody is nice. They just want to know what had happened to me and they don’t make [comments or remarks], not at all, everybody is nice.” 4.1.2.2. Large Groups Sympathy in interaction with large groups engenders a variety of results that include both comfortable and un- comfortable situations. Tom states: “Depends on whether or not I’m wearing my prosthesis, the black patch or the medical patch and I get different reactions for each of those circumstances. When I’m wearing my prosthesis out in public… they do not know that I had surgery. If I wear it … on the street, in the store, in front of a group of people, at church or in a meeting, if they do not know I had surgery they still do not know I had surgery. [Because it is difficult to wear my prosthesis continuously]5, I wear my black patch. When I wear my black patch, I get better service. If I ride a plane… people treat me differently… they are sympathetic, overtly so… This is a person with a visual problem, we’ll treat him differently and they do…. I think they feel sorry for me… They seem to be more sympathetic towards me and more ready to help me in stores, primarily in store settings or at the library or other public places. When I’m out in public service areas, the service that I receive appears to be somewhat more magnanimous… I’m going to take advantage of this thing as much as I can.” But he also indicates: “Sympathy is good, but at times I feel that I don’t need it at all. I can do things on my own and do not need any help.” Mary says: “I’m very self-confident … around others because more and more people are very receptive of cancer survivors. So if you had cancer and you are a survivor, then people are very supportive…. I could be a horrible person (I’m not a horrible person) and they would be like ‘oh, that’s ok if you are a cancer survi- vor…. People at work have been very supportive… no- body has been negative about my appearance…. They simply ask what happened to you.” 4.1.3. Benign Neglect 5This patient informs us that wearing the prosthesis creates a number of problems. There are problems associated with skin irritation where the prosthesis attaches to the face. When the skin is irritated, the dis- comfort forces the patient to wear either a black patch or a medical atch. Addi ionally, there are problems associated with the patients’ activities. Wearing the prosthesis causes severe headaches when trav- eling by plane. Discomfort is also felt when pursuing outdoor activities or exercising.  A. Bonanno et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 418-428 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/Openly accessible at 425 425 Benign neglect refers to situation in which interacting individuals did not pay particular attention to patients. In the case of interaction with small groups, data show that varying patterns of interaction are possible. In some in- stances, lack of interests on the part of interacting indi- viduals is felt and acted upon in positive terms. Disfig- ured patients do not feel stigmatized. Simultaneously, though, similar situations engender opposite interaction patterns as patients feel uncomfortable in the absence of attention paid to them. The fact that interacting indi- viduals “ignore” patients is not necessary an indication of comfort in interaction. In the case of interaction with large groups, benign neglect generates comfortable in- teraction patterns. The size of the group is a condition that allows patients to pass unnoticed and this situation facilitates the manner through they interact with this group of strangers. 4.1.3.1. Small Groups Following are a few instances of the consequences of benign neglect in interaction with small groups. Carl says: “I have not noticed anything. I don’t think people feel sorry for me any more or any less. I think that still they see me as Carl… When I’m with a small group of people, I don’t see anyone doing anything dif- ferently for me… They treat me the same as always… When I go shopping people look at me… it doesn’t feel good but I don’t let it bother me, I don’t feel like I’m less of a human. I don’t have to look down like I’m ashamed to look them in the face, or like they are going to reject me or anything like that…. It bothers me though.” Ron states: “I generally try to avoid being seen in a prominent position… I really do believe that I have learned to accept it [my disfigurement], but I do realize that it’s noticeable to people and that it’s pretty obvi- ous. … I felt good about myself before my cancer. Now, I look in the mirror and I’m missing a part that’s very important to your looks…people at work tell me ‘I don’t even notice that your eye is missing, because I’m so used to you…. It bothers me, but I accept it.” 4.1.3.2. Large Groups Joy provides an instance of benign neglect in interaction with large groups. She says: “We [my husband and I] go to [college] basketball games. We have a lot of those here. At the basketball game is different because everyone is so intent on what [the players] are doing what they are watching that they do not pay attention to anybody, because I mean, they are glued on what is going on on the court so I don’t notice people reacting to me…. I’m pretty confident interacting with people except when I need to meet new people… I used to love meeting new people. I don’t really enjoy that so much anymore… but I like to be in a large crowd when people don’t notice you.” 4.2. Always Comfortable Patients Always comfortable patients are individuals who do not experience problems interacting in small and large groups alike. They are well adjusted to their disfigured status and, while they encounter behavior that could lead to enacted stigmatization, the interaction does not affected by them. As episodes of enacted stigmatization are quire rare, the lack of felt stigmatization denotes non-stigmatizing interaction patterns. Basic statistics about this group are summarized in Table 2. As it can bee seen from that table, no relevant differences seem to exist in terms of patients’ age and gender. Fred says: “I feel no difference the way that people treat me… I don’t see any difference… when we go to the shopping mall, when we go to the restaurant, when we go anywhere. I see no difference in the way I’m treated now and the way I was treated five years ago [before surgery]…. I have no problems with the way I look whenever I’m meeting anyone. It’s not something that I think about and it’s something that I don’t even consider…. I get some sympathy because I’m a cancer survivor, but this has very little to do with the way I look.” Frank continues: [when I interact with people I’m very confident] Oh, yeah, I think so. I went back to work on a full-time job where I used to travel a lot and go to a contractor’s facility in [name of city]… all the time and meet with people, have meetings, give briefings and so, … I don’t have any issue with it and there never seemed to be an issue with those people I deal with.” [When I go out] “the only people that tend to react are kids. And they’ll look at you, and it is just like at my wife’s church preschool class. I went to see her at her class today and went to lunch after that, and the kids came up and just looked and said, hey, how you doin’? And she said, oh, my husband’s a pirate… they said, okay, great!... I haven’t really had a negative situation so far…. When I had my knee operation the anesthesiolo- gist that did the knee operation came to my house during Halloween and I answered the door and he was standing there with his child, and he said: you’re really getting into the part, aren’t you? Thinking that I had an eye patch on for Halloween. I said, nope, I really have to have an eye patch. He said: Oh, I’m sorry. That’s the guy I had four months later to be my anesthesiologist on my knee surgery, and he mentioned how he had met some- one with an eye patch. I said that was me. He said: Oh, I feel so bad about it. I said: don’t worry, it happens all the time. You know, you get dressed up for something or whatever… but… it doesn’t bother me and in fact I called the guy about a part on a pool the other day, told him my name, he said: yeah, you are the guy with the bad eye – wait, you don’t mind that I said that, do you?’ And I said, no, I don’t mind that you said that.”  A. Bonanno et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 418-428 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 426 Openly accessible at 5. CONCLUSIONS In terms of the interaction between facially disfigured cancer survivors and secondary groups, this study identi- fied the existence of two groups of patients. When inter- acting with strangers and acquaintances these cancer survivors can be grouped into always comfortable pa- tients and occasionally comfortable patients. Always comfortable patients are patients who do not experience problems because of their disfigurement and their inter- action with small and large groups does not lead to felt stigmatization. While episodes of enacted stigma may occur, they tend not to affect these well adjusted indi- viduals, their counterparts, and interaction. The group of patients classified as occasionally com- fortable presents more complex patterns of interaction with secondary groups. This group experiences uncom- fortable and stigmatizing interaction patterns in specific instances. At the same time, they experience non consis- tent or comfortable (i.e., not stigmatizing) patterns of interaction in other situations. This is the group of pa- tients that requires the most attention as their interaction with secondary groups varies according to the size of the group. These findings add to the existing literature in a num- ber of ways. First, they indicate that strangers do display varying patterns of interaction with the facially disfig- ured. Accordingly, the statement that “the reaction of people on the streets or in the neighborhood is …. con- sistent: they stare at most patient with facial defect” [39] (see also [15,16]) needs to be revised. This study dem- onstrates that the behavior of strangers is much more complex than previously recorded and it entails a num- ber of distinct interaction patterns. Second, this research clarifies questions raised by previous research on the interaction between facially disfigured cancer survivors and acquaintances [39]. Data on the various patterns of interaction within small groups demonstrate the complexity of interaction patterns ex- isting between patients and acquaintances. Ultimately, acquaintances are the source of stigmatization and sup- port alike as they intrude in the everyday existence of patients but also provide sympathy to cancer survivors. Third, these findings contribute to the understanding the issue of the relationship between disfigurement and cancer. The existence of cancer mitigates the negative effects of facial disfigurement. It creates a process of interaction in which people display support to patients because they suffered from cancer. Once people learn that the patient’s facial disfigurement is cancer related, they tend to be overtly supportive regardless of other conditions. Finally, this research underscores the importance of the reading of the social consequences of cancer gener- ated facial disfigurement in relational terms. The social consequences of facial disfigurement emerge as out- comes of interaction processes. As such, they involve patients and other segments of society as they interact in various social spheres. While the study of the manner through which individuals respond to disfigurement re- mains important, it is through the process of interaction that stigmatization or lack of it are constructed. Three overall recommendations emerge from the analysis presented in this study. First, patients should be warned about the occurrence of possible difficulties when interacting in large and small groups alike. In this respect, they should be prepared to the possibility of experiencing episodes of intrusion, sympathy and benign neglect when interacting with small and large groups of acquaintances and strangers. Second, it appears desirable that interacting groups be sensitized about the patterns of interaction identified above. While complex, this solu- tion should be considered as educational programs are discusses and implemented at various levels. Finally, the issue of the social consequences of cancer generated facial disfigurement should be studied with an interdis- ciplinary approach. In this context, it would be desirable to include a sociological component that would allow investigators to explore the collective dimension of the social construction of facial disfigurement and stigma. REFERENCES [1] Mood, D.W. (1997) Cancers of the head and neck. In: Varricchio, C., Ed., A Cancer Source Book for Nurses, Jones and Bartlett Publishers, Sudbury, 271-283. [2] Davis, K., Wingo, P. and Parker, S. (1998) Cancer statis- tics by race and ethnicity. CA: A Cancer Journal for Cli- nicians, 48(1), 31-48. [3] Davis, K., Roumanas, E.D. and Nishimura, R.D. (1997) Prosthetic-surgical collaboration in the rehabilitation of patients with head and neck defects. Otolaryngologic Clinics of North America, 30(4), 631-645. [4] Dropkin, M.J. (1999) Body image and quality of life after head and neck cancer surgery. Cancer Practice, 7(6), 309-313. [5] American Cancer Society. (2008) Detailed guide: Eye cancer. http://www.cancer.org [6] Esmaeli, B. (ed.) (2009) Ophthalmic Oncology, Springer, Norwell. [7] Anderson, R.C. and Franke, K.A. (2002) Psychological and psychosocial implications of head and neck cancer. Internet Journal of Mental Health, 1(2), 55-64. [8] Cole, J. (1998) About face. The MIT Press, Cambridge. [9] Jackson, L.A. (2002) Physical attractiveness: A socio- structural perspective. In: Cash, T.F. and Pruzinsky, T., Eds., Body image. A handbook of theory, research, and clinical practice. The Guilford Press, New York, 13-21. [10] Kish, V. and Lansdown, R. (2000). Meeting the psycho- social impact of facial disfigurement: Developing a clinical service for children and families. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 5(4), 497-512. [11] Macgregor, F. (1990) Facial disfigurement: Problems and  A. Bonanno et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 418-428 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/Openly accessible at 427 427 management of social interaction and implication for mental health. Aesthetic and Plastic Surgery, 14(4), 249- 257. [12] Furness, P., Garrud, P., Faulder, A. and Swift, J. (2006) Coming to terms. A grounded theory of adaptation to fa- cial surgery in adulthood. Journal of Health Psychology, 11(3), 453-466. [13] Goffman, E. (1963) Stigma. Notes on the management of spoiled identity. Simon & Shuster, New York, 2-52. [14] Hawkesworth, M. (2001) Disabling spatialities and the regulation of a visible secret. Urban Studies, 38(2), 299- 318. [15] Hughes, M. (1998) The social consequences of facial disfigurement. Ashgate, Aldershot, 24-279. [16] Macgregor, F. (1974) Transformation and identity: The face and plastic surgery. Quadrangle/The New York Times Book Co, New York, 8-208. [17] Bull, R. and Rumsey, N. (1988) The social psychology of facial appearance. Springer Vale, New York. [18] Cash, T.F. and Pruzinsky, T. (eds.) (2002) Body image. A handbook of theory, research, and clinical practice. The Guilford Press, New York. [19] Bull, R. and Stevens, J. (1981) The effects of facial dis- figurement on helping behavior. The Italian Journal of Psychology, 8(1), 345-351. [20] Callahan, C. (2004) Facial disfigurement and sense of self in head and neck cancer. Social Work in Health Care, 40(2), 73-87. [21] Kent, G. (2000) Understanding the experiences of people with disfigurements: An integration of four models of social and psychological functioning. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 5(2), 117-129. [22] Clarke, A., Rumsey, N., Collin, J.R.O. and Wyn-Williams, M. (2003) Psychological distress associated with disfig- uring eye conditions. Eye, 17, 35-40. [23] Newell, R.J. (1999) Altered body image: A fear-avoid- ance model of psycho-social difficulties following dis- figurement. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 30(5), 1230- 1238. [24] Pruzinsky, T., Levine, E., Persing, J.A., Barth, J.T. and Obrecht, R. (2006) Facial trauma and facial cancer. In: Sarwer, D.B., Pruzinsky, T., Cash, T., Goldwyn, R.M., and Persing, J.A., Eds., Psychological aspects of recon- structive and cosmetic plastic surgery: Clinical, empiri- cal and ethical perspectives, Lippincott Williams, Phila- delphia PA, 125-143 [25] Thompson, A. and Kent, G. (2001) Adjusting to disfig- urement: process involved in dealing with being visibly different. Clinical Psychology Review, 21(5), 663-682. [26] Strauss, A. (1987) Qualitative analysis for the social sci- entists. Cambridge University Press, New York. [27] Fife, B.L. and Wright, E.R. (2000) The dimensionality of stigma: A comparison of its impact on the self of persons with HIV/AIDS and cancer. Journal of Health Social Behavior, 42, 50-67. [28] Cahill, S. and Eggleston, R. (1995) Reconsidering the stigma of physical disability: Wheelchair use and public kindness. The Sociological Quarterly, 36(4), 681-698. [29] Susman, J. (1994) Disability, stigma and deviance. Social Science and Medicine, 38, 15-22. [30] Angermeyer, M. and Matschinger, H. (1994) Lay beliefs about schizophrenic disorder: The results of a population study in Germany. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 89, 39-45. [31] Corrigan, P.W. and Penn, D.L. (1999) Lessons from so- cial psychology on discrediting psychiatric stigma. American Psychologist, 54, 765-776. [32] Clarke, A. (1999) Psychosocial aspects of facial disfig- urement: problems, management and the role of a lay-led organization. Psychology, Health and Medicine, 4(2), 127-142. [33] Synnott, A. (1989) Truth and goodness, mirrors and masks—Part I: A sociology of beauty and the face. The British Journal of Sociology, 40(4), 607-636. [34] Link, B.G. and Phelan, J.C. (2001) Conceptualizing Stigma. Annual Review of Sociology, 27, 363-385. [35] Jacobi, A. (1994) Felt versus enacted stigma: A concept revisited. Social Science and Medicine, 38(2), 269-274. [36] Feingold, A. (1992) Good looking people are not what we think. Psychological Bulletin, 111, 304-341. [37] Hagedoorm, M. and Molleman, E. (2006) Facial disfig- urement in patients with head and neck cancer: The role of social self-efficiency. Health Psychology, 25(5), 643- 647. [38] Rybarczyk, B.D. and Behel, J.M. (2002) Rehabilitation medicine and body image. In: Cash, T.F. and Pruzinsky, T., Eds., Body image. A handbook of theory, research, and clinical practice. The Guilford Press, New York, 387-393. [39] van Doorne, J.M., van Waas, M.A. and Bergsma, J. (1994) Facial disfigurement after cancer resection: A problem with an extra dimension. Journal of Investiga- tive Surgery, 7(4), 321-326. [40] Bonanno, A. and Choi, J.Y. (2009) Psychosocial aspects of orbitofacial disfigurement in cancer patients. In: Es- maeli, B., Ed., Ophthalmic Oncology, Norwell, Springer, 96-105. [41] Millsopp, L., Brandom L., Humphris, G. and Lowe, D. (2006) Facial appearance after operations for oral and oropharyngeal cancer: A comparison of case notes and patient-completed questionnaire. British Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 44, 358-363. [42] Valente, S. (2004) Visual disfigurement and depression. Plastic Surgical Nursing, 24(4), 14-146. [43] Partridge, J. (1998) Changing faces: Taking up Macgre- gor’s challenge. Journal of Burn Care and Rehabilitation, 19, 174-180. [44] Vickery, L.E., Latchford, G., Hewinson, J., Bellew, M. and Faber, T. (2003) The impact of head and neck cancer and facial disfigurement on the quality of life of patients and their partners. Head & Neck, 25(4), 289-296. [45] Bonanno, A., Choi, J.Y. and Esmaeli, B. (2008) The con- tradictions of medical sociology understanding of stigma in facially disfigured individuals. Annual Meeting of the Southwest Social Science Association, Las Vegas. [46] Mosher, C. and Danoff-Burg, S. (2007) Death anxiety and cancer related stigma: A terror management analysis. Death Studies, 31, 855-907. [47] Berremberg, J.L. (1989) Attitudes towards cancer as a function of experience with the disease: A test of three models. Psychology and Health, 3, 233-243. [48] Bloom, J. and Kessler L. (1994) Emotional support fol-  A. Bonanno et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 418-428 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/Openly accessible at 428 lowing cancer: A test of the stigma and social activity hypothesis. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 35, 118-133. [49] Weiner, B., Perry, R.P. and Magnusson, J. (1988) An attributional analysis of reaction to stigma. Journal of Social Issues, 35(1), 120-155. [50] Glaser, B. and Strauss, A. (1987) The discovery of grounded theory. Aldine Transaction New Brunswick, NJ.

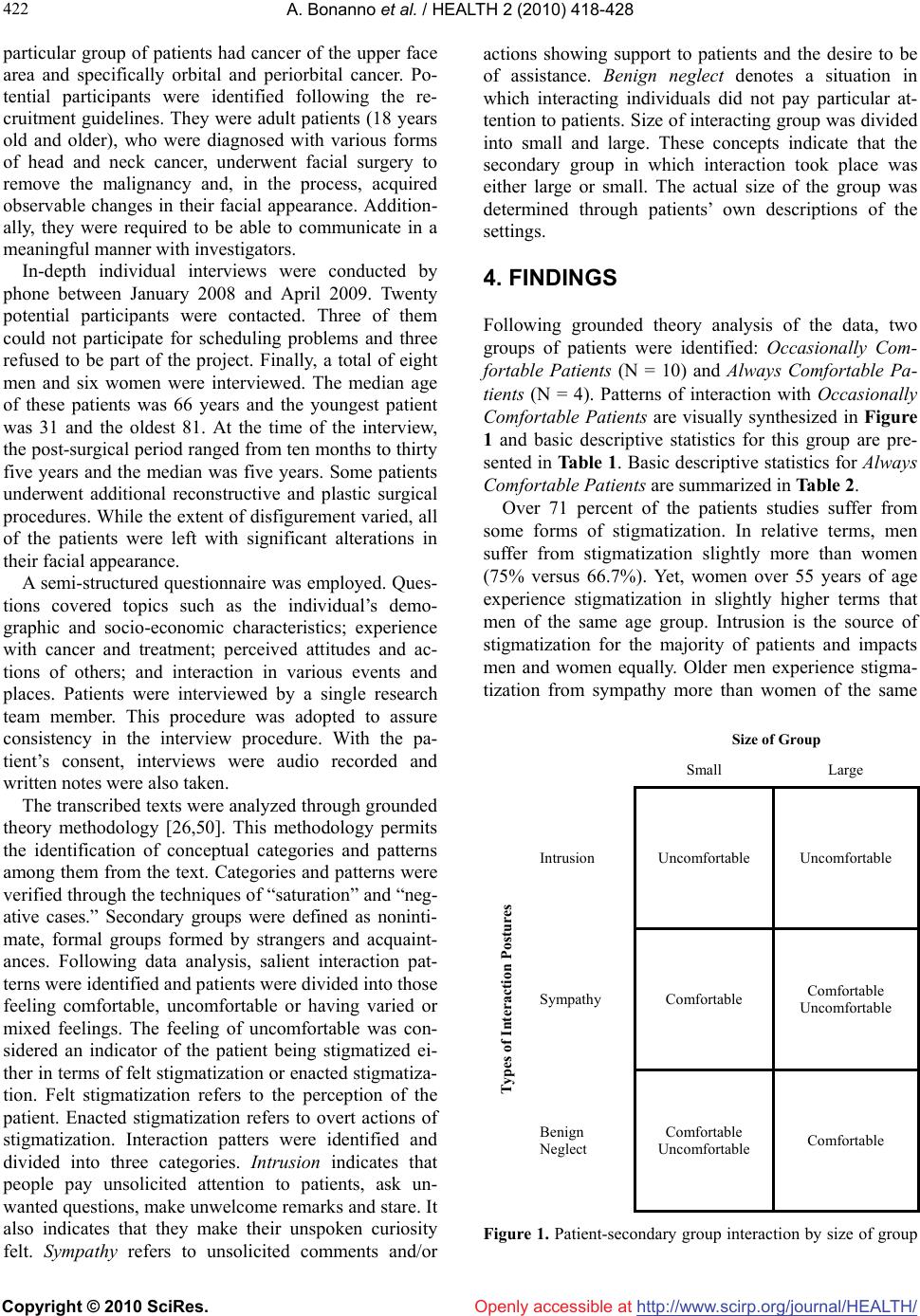

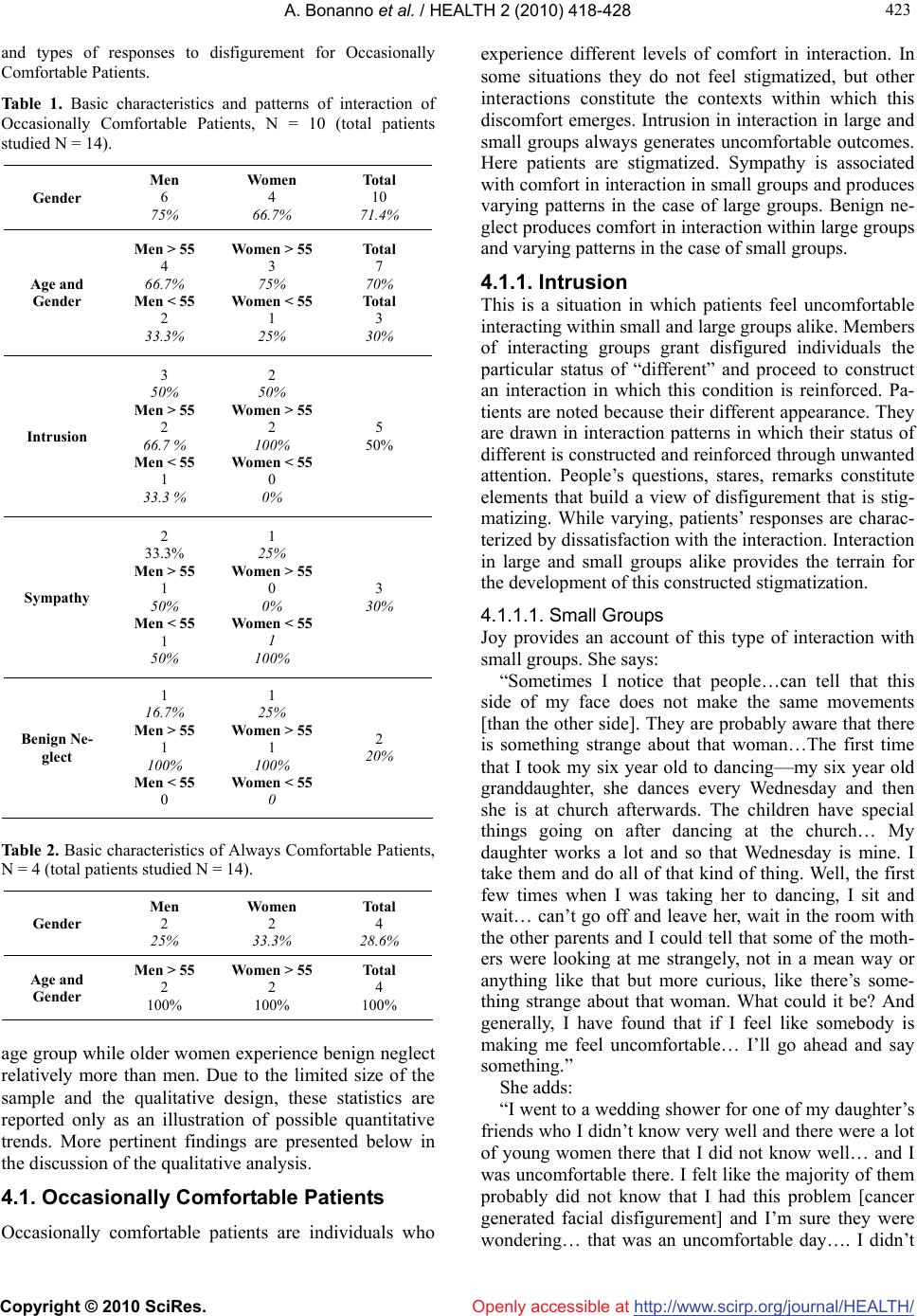

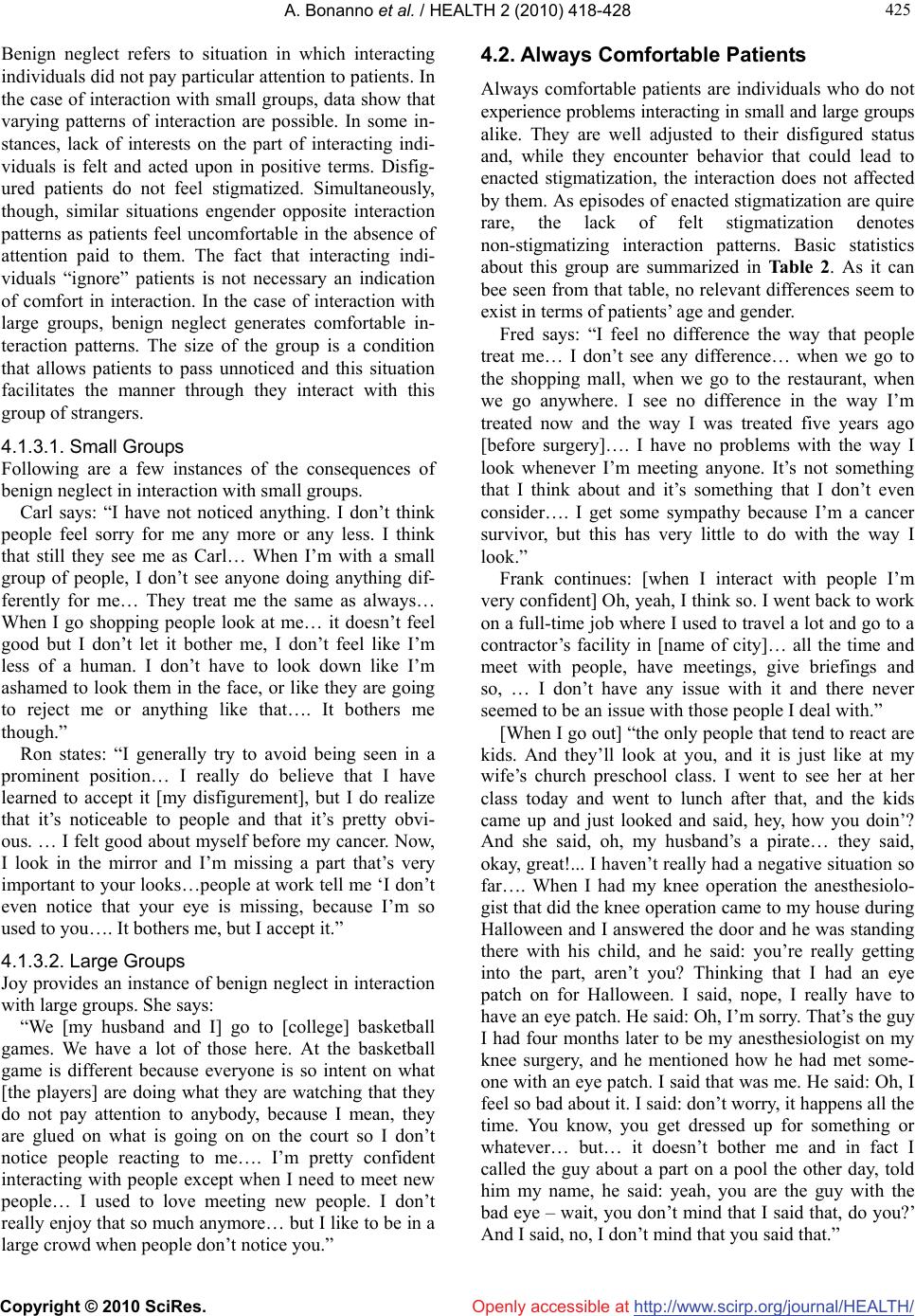

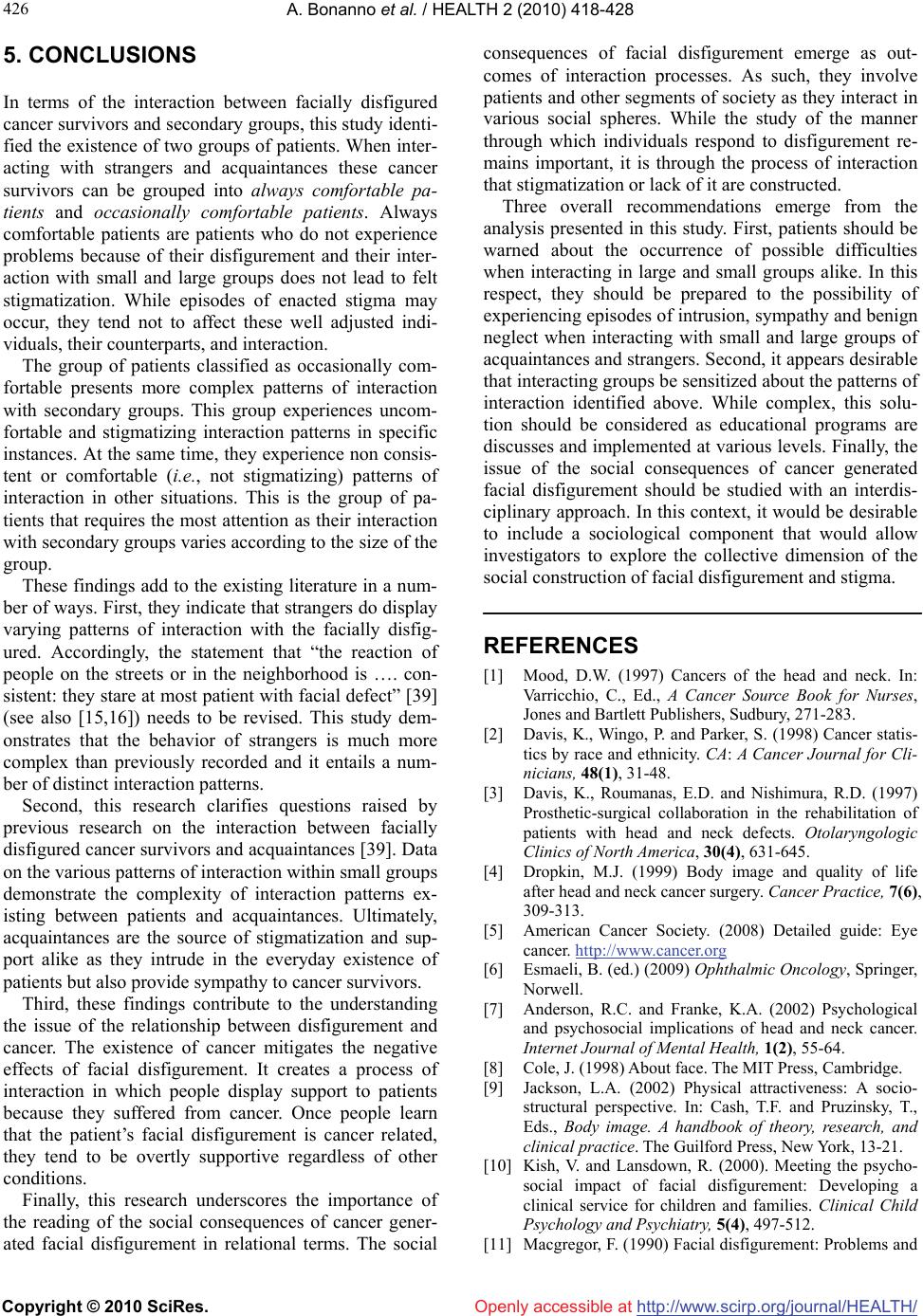

|