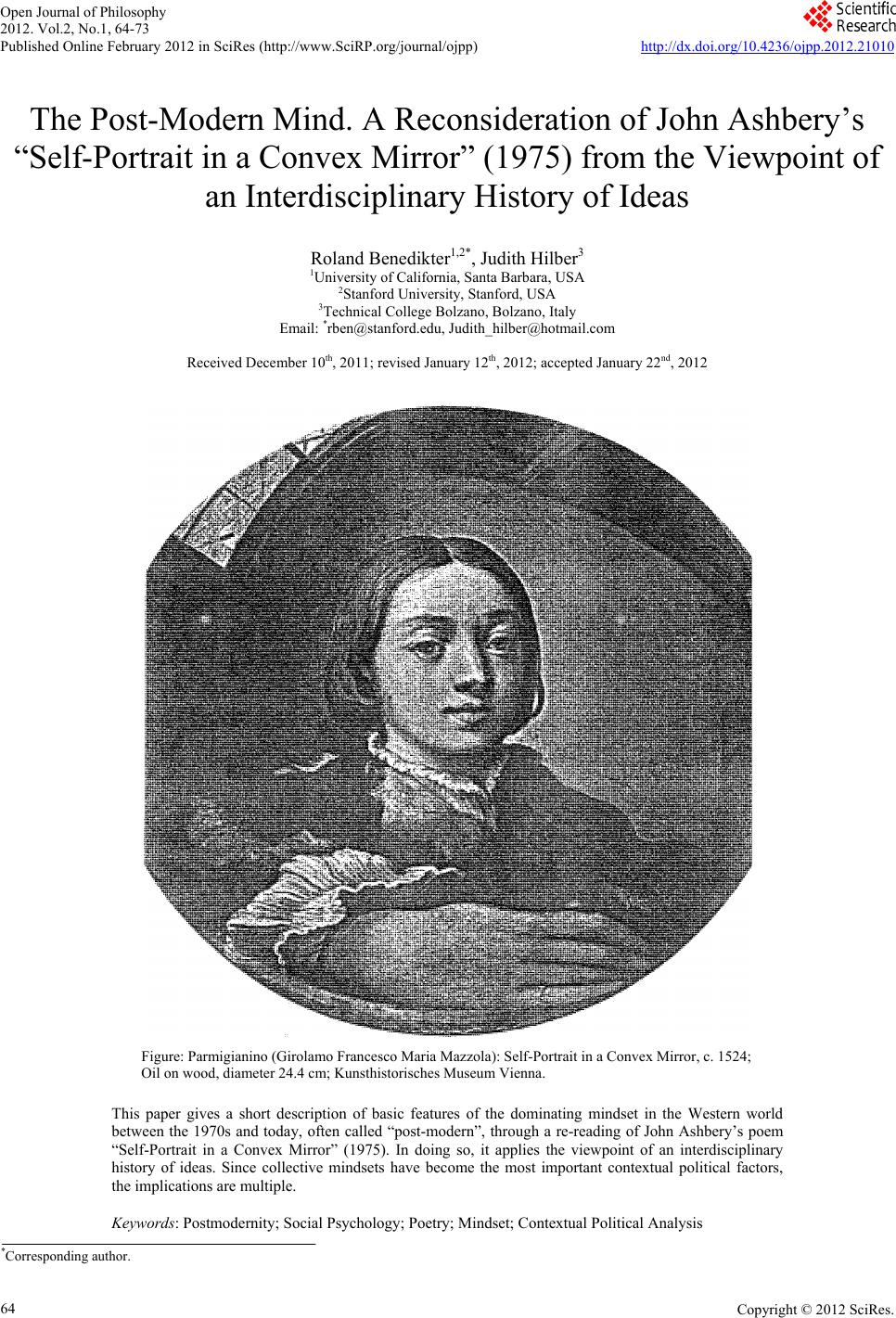

Open Journal of Philosophy 2012. Vol.2, No.1, 64-73 Published Online February 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ojpp) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojpp.2012.21010 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 64 The Post-Modern Mind. A Reconsideration of John Ashbery’s “Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror” (1975) from the Viewpoint of an Interdisciplinary History of Ideas Roland Benedikter1,2*, Judith Hilber3 1University of California, Santa Barbara, USA 2Stanford University, Stanford, USA 3Technical College Bolzano, Bolzano, Italy Email: *rben@stanford.edu, Judith_hilber@hotmail.com Received December 10th, 2011; revised January 12th, 2012; accepted January 22nd, 2012 Figure: Parmigianino (Girolamo Francesco Maria Mazzola): Self-Portrait in a Convex Mir ror, c. 1524; Oil on wood, diameter 24.4 cm; Kunsthistorische s Museum Vienna. This paper gives a short description of basic features of the dominating mindset in the Western world between the 1970s and today, often called “post-modern”, through a re-reading of John Ashbery’s poem “Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror” (1975). In doing so, it applies the viewpoint of an interdisciplinary history of ideas. Since collective mindsets have become the most important contextual political factors, the implications are multiple. Keywords: Postmodernity; Social Psychology; Poetry; Mindset; Contextual Political Analysis *Corresponding author.  R. BENEDIKTER ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 65 Introduction: Literature and Philosophy Anticipating the Post-Modern Mind The Epistemological Aspect in the Poem The Mutual Influence of Thing and Perceiver All media are extensions The opening of the poem outlines the genesis of the painting, and here Ashbery introduces the leitmotif of “Self-Portrait”: complementarity and reciprocation. The first reciprocal de- pendence captures and reveals the writer’s theory of the rela- tionship between subject and object. His epistemological notion is deeply rooted in, and originates from the principle of rela- tiveity, according to which events and items, abstract or spe- cific, “are perceived with reference to a certain frame.”3 From the outset, a universal validity is undermined, if not rendered virtually inexistent. For Asbery, not even the soul exists in its a priori purity, without the sensory and tactile perception of the recipient. of some human faculty— psychic or physical Marshall McLuhan Four years before the publication of Jean-Francois Lyotard’s seminal treatise “The Postmodern Condition” (1979)1—which provided the name to the “post-modern” movement in literature, philosophy and the arts, and in this way branded a mindset that was to dominate the cultural paradigm of the West throughout the following decades—American poet John Ashbery antici- pated most of the decisive traits of this worldview and attitude in an epochal poem, “Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror” (1975). This prescient vision confirmed the close relation between the literature, philosophy and social psychology of his time. In fact, Ashbery’s poem is not only a meditation on art, but also an early and most lively description of the “post-modern” mindset, destined to remain valid for decades, up to the present day. In it, painting and writing are closely examined, while the gestalt of a passage in the history of the Western mind is taking shape. The soul has to stay where it is, Even though restless, hearing raindrops at the pane, The sighing of autumn leaves, thrashed by the wind, Longing to be free, outside, but it must stay Posing in this place.4 Indeed, the soul is treated as if it were some matter, some material fenced in by the look of the perceiver, who accepts natural borders and material limits, but cannot apply those that are imaginary or virtual. Our concept of space, if experienced directly, is always both limited by and extended through sight, which intercepts the borders of physical surroundings. This limitation is defined either by the objects or walls within a room; outside a room, i.e. outdoors the borderlines are the con- tours of buildings, plants, etc., the skyline, a cloud, etc. Theo- reti- cally speaking, we can discuss “space” in abstract terms, but in practice we lack the ability to experience this metaphysi- cal unity of going beyond our material world. As appropriate for—and consistent with—the structural dou- blefacetedness of the post-modern mind, the author plays a double role in his poetical endeavor. As the writer of the poem he is an artist; whereas in discussing Parmigianino’s painting in the poem he becomes an art critic. The unusually long poem (over 500 lines long2) begins with a very neutral language, a catalogue of descriptive facts about Parmigianino taken from Giorgio Vasari. Consecutively Ashbery’s examination drives both the author and the reader backwards on a journey to Par- migianino’s self-portrait, into which one enters as if it were a self-projection of the author, to which the reader must witness. In fact, Parmigianino’s painted ego manifests itself as Ashbery’s psychic extension. Drawn closer and closer, the extension is overcome and Ashbery’s identification takes place, until he once again frees himself and retreats back to his original posi- tion. The dual aspect, extended to numerous subjects, becomes important for an appreciation of the entirety of poem. The po- etic flow feeds upon such dualities, and creates dichotomies, only to unify them later. “The surface is what’s ther e And nothing can exist except what’s there.” (70) Thus the soul must adhere to the surface of the picture. The surface Of the mirror being convex, the distance increases Significantly; that is, enough to make the point That the soul is a captive, treated humanely, kept In suspension, unable to advance much farther In this essay we attempt to identify and investigate some of these dualisms and ambivalences in the poem, with special regard to Ashbery’s position in the post-modern movement. In particular, we seek to elucidate the interdependence of con- trasting and divergent factors as a principle of complementarity that Ashbery—representative of the post-modern worldview— elevates to the level of a philosophy of life. In addition, a gen- eral view of self-portraiture, using the example of Parmigianino, will be given. Than your look as it intercepts the picture. (68-69) It is a captive of two powers, the piece of wood or canvas that has a clear-cut shape, and of our visual discrimination de- fined by this very shape. Hence the thing and its human percep- tion cannot be separated and examined individually. They are so tightly linked that one presupposes the other and vice versa (determiners are intentionally used, instead of the names in order to avoid giving priorities). In fact, a compromise between a priori and a posteriori theories is suggested, as a potential— and equalizing—solution. The equipment, human and material, created at the same time, equally presuppose and influence each other. 1J.-F. Lyotard, The Postmodern Condition, University of Minnesota Press 1984. 2Charles Molesworth, The Fierce Embrace: Study of Contemporary merican Poetr , Columbia and London: Missouri UP, 1979, 177. 3Jerome Klinkowitz, Rosenberg, Barth es, Hassan: The Postmodern Habit o Thought, At hens and London: Georgia UP, 1988, 12 8. 4John Ashbery, Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror, New York: The Viking Press, 1975, 69. All further references are to this edition and will occu parenthetically in the text; the poem will hereafter be abbreviated as SP. 5Klinkowitz 1988, 124. 6Friedrich Nietzsche, “The Birth of Tragedy from the Spirit of Music” and “The Genealogy of Morals,” trans. Francis Golffing, New Yo rk: Doubleday Anchor Pre ss, 1956, 98f f. In comparison, Nietzsche’s early attempts at distinguishing between the essence and appearance of a thing, for instance, is contrary to Ashbery’s. In Ashbery’s and the postmodernists’ view “the art medium’s being [is] an extension of the physical world,”5 that is to say, all works of art, including musical com- positions, which are, according to the early works of Nietzsche (and which he later criticized himself) the representation of the thing-in-itself,6 they are the “things” themselves as perceived  R. BENEDIKTER ET AL. by the reader, spectator, and/or beholder. In different percipi- ents a work of art, e.g. a symphony, can evoke different reac- tions and kindle dissimilar emotions. The symphony is all the interpretations it evokes in the listeners; it could not exist without a composer having written it. Furthermore, it would be worthless without people listening to it. The evoking of feelings in the listeners on the one hand, and their reception on the other hand, exemplify the mutual dependence of the thing and the sensory apparatus and perceptual response of the human being. The Giving and Taking of the Individual in His/Her Surrounding World Ashbery touches upon a highly philosophical explanation of the self and of character in general. A person can never be a single type, but instead corresponds to the potpourri-thinking of postmodernism. Various cooks add herbs and spices to the stew and thus either contribute to or spoil the quality of the taste. This metaphor demonstrates that an individual can never be seen in isolation of his/her milieu, because an individual as “pure” or disembedded as this cannot even exist. To be sure, the human being—in being human—is inextricably nested within her/his time, place and circumstances, and s/he can be positively or negatively influenced by these forces. “The tine self-important ship/On the surface” (70) has to be aware of the “dozing whale on the sea bottom.” The same picture of the apotheosis of the individual was employed by Nietzsche in The Birth of Tragedy, in which the individual sits “quietly in his rocking rowboat in mid-sea, absorbed in contemplation,”7 and dreams as the Apollonian principle of individuation, half- awakened by Dionysiac intoxication, amidst the outer restless- ness of the waves. A human being cannot, under normal circumstances, escape social contact, either directly nor indirectly. In association with, and engaging our fellow human beings, and in our entangle- ment with all kinds of media—ranging from the most tradi- tional, such as newspapers and books, to the more progressive audio-visual and electronic means of communication, such as television, computers and the internet, respectively—we per- ceive both consciously and unconsciously. As Wordsworth claimed, well before the age of electronic communication, The eye it cannot choose but see; We cannot bid the ear be still; Our bodies feel, where’er they be, Against, or with our will.8 All data, as if liquid sucked up by a sponge, are partly ab- sorbed and kept and partly dropped off again. This is the proc- ess of what we herein refer to as humans’ “psychological me- tabolism”. The human persona is influenced by (and of course, influences) its environment. Not only does this milieu theory apply subjectively, as expressed by Wordsworth, but this is also an objective event. This means that in the former way the indi- vidual is shaped by the outer forces and undergoes an active change as the subject. Moreover, it can also function as the object, and in this way an individual is passively moulded by the definitions of his/her fellow people. Applying adjectives and attributes to the “object” of how other people perceive and judge this very character, and how they form descriptions and opinions can vary drastically. Contradictory opinions about someone are in accord with the liking and disliking of this person, taking into account friends and foes as authorized critics. Although such criticisms might not effect an all-out change of one’s disposition, it can never- theless be seriously regarded as a potentially powerful force of influence. Such suggestive manipulation is quite often underes- timated, causing an alleged indifference. However, in one way or another, consciously or subconsciously, we do react to statements and utterances about ourselves: we try to assert and defend ourselves, justify our behaviour, take pride or offense, etc. As Ashbery notes, Parmigianino too, is influenced by other people—the changes taking place in him are painted into the picture and become part of his nature. The painting freezes the positive and negative phrases, the “light” and “dark” speech of his friends and acquai ntances: How many people came and stayed a certain time, Uttered light or dark speech that became part of you, Like light behind windblown fog and sand, Filtered and influenced by it, until no part Remains that is surely you. Those voices in the dusk Have told you all and still the tale goes on In the form of memories deposited in irregular Clumps of crystals. (71) The Self-Portrait and Its Purose Its Intrinsic F unc tion Regardi n g Parm igianino In traditional self-portraiture a self-representation usually portrays the bust, focusing upon the head, and especially the face and its expression. The rest of the body is left out, cut off so to say, because it is not considered expressive enough of the character. Ashbery takes a painter’s perspective of self-image to his, plot “of the poem. At first, his dramatization of Par- migianino’s painting seems a random and eccentric decision, a game played for its pleasure without any deeper motivation. Ashbery plays a game indeed, but at the same time he opens fertile ground by conveying his thought associations arising from the painting. Ashbery’s fascination for the portrait can be ascribed first to its fragmentary appearance, a key word of the postmodern period (which will be discussed later), and second to its idiosyncratic presentation on the surface of a round con- vex piece of poplar wood as its panel.9 The painting shows Parmigianino’s angelic face and his huge but tender, delicately formed hand, …big enough To wreck the sphere, and too big, One would think, to weave delicate meshes That only argue its further detention. (70) The face, taking up the geometrical centre of the circle, is partially diminished as an optical centre by the counterbalance of the hand as another optical attraction. The hand at the bottom of the picture arouses an alienating effect that is further height- ened by its immensity. Usually portraits omit the hands and in this way might be considered to be severing; but Parmigian- ino’s painting the right hand into the picture is deliberate and therefore assumes a significant function, by speaking more 7Nietzsc he 1956, 33-34. 8William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Expostulation an epl . Lyrical Ballads (1805), ed. Derek Roper, 3rd ed., Plymouth: North- cote House, 1987, 5. 9Lili Fröhlich-Blum, Parmigianino und der Manierismus. Wien: Anton Schroll, 19 21, p. 6. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 66  R. BENEDIKTER ET AL. inclusively through a language conveyed by the body, as well as the face. Self-portraits very often depict and summarize an artist’s life, reflecting his philosophical evolution. A good portrait reveals a synthesis of the psychological structure of the painter (likewise an autobiography, viz. a self-portrait in literature).10 In this way, character is conveyed as trying to break free through the eyes, thereby allowing the artist’s soul to open up and displays the inner truth of the self-portraitist, The soul establishes itself. But how far can it swim out through the eyes And still return safely to its nest? (68) In order not to let his soul, and inner secrets extend too far, Parmigianino holds up his right hand, which is Bigger than the head, thrust at the viewer And swerving easily away, as though to protect what it advertises. … Your gesture which is neither embrace nor warning But which holds something of both in pure Affirmation that doesn’t affirm anything. (68…70) The hand is significant insofar as it discloses a double func- tion. It is there, offered to the viewer as a greeting and wel- coming sign. But at the same time Parmigianino is careful not to fully expose himself to the onlooker, and uses his hand as a shield to hide his private exhibitionism. Thus, the hand sym- bolizes both a link and a wall to other people, in other words an expression of the painter’s extroversion and inner privacy.11 The creation of the self-portrait is the creation of the artist himself. A constant dialogue underlies the act of painting, an argument between the painter and his reflection in the mirror and his evolving image of the reflection on the painted surface. An antagonistic analysis of the spiritual and psychological do- mains of the artist is performed that scans and generates a rep- resentation of his “self”. Investigating his inner plurality, the artist embarks on the quest for his own myth of his past,12 try- ing to come to terms with his duality. The dichotomy of the artist and his reflection, his ego and super-ego is balanced in a synthesis of the reflection of the reflection, in the result of a long “process of psychological self-exploration.”13 Its Exterior Influence on Ashbery Thus the genesis of the work is given great emphasis, whereas the end product, the concluded painting, is fixed and immobile; “It must move/As little as possible.” (69) A whole personality is reduced to one image, one picture, frozen into one specific time, at one specific place. A levelling out and boiling down to a single representation of the “magma of inte- riors” takes place at the expense of all of a life’s ups and downs of myriad moments. The secret is too plain. The pity of it smarts, Makes hot tears sp u r t: that the soul is not a soul, Has no secret, is small, and it fits Its hollow perfectly: its room, our moment of attention. (69) Although Ashbery feels compassion, if not pity, for a person who was complex, even rich in the meaning and manifestation of daily banalities, but is now reduced to one single image: Long ago The strewn evidence meant something, The small accidents and pleasures Of the day as it moved gracelessly on, A housewife doing chores. Impossible now To restore those properties in the silver blur that is The record of what you accomplished by sitting down “With great art to copy all that you saw in the glass” So as to perfect and rule out the extraneous Forever (71-72), Ashbery must admit to himself that “Something like living occurs, a movement/Out of the dream into its codification.” (73) This mystification so utterly captivates him that his own self becomes a replacement of Parmigianino. What is novel is the extreme care in rendering The velleities of the rounded reflecting surface (It is the first mirror portrait), So that you could be fooled for a moment Before you realize the reflection Isn’t yours. You feel then like one of those Hoffmann characters who have been deprived Of a reflection, except that the whole of me Is seen to be supplanted by the strict Otherness of the painter in his Other room. (74) Being completely absorbed in the painting, Ashbery identi- fies with Parmigianino for a short time. This act of supplanta- tion and exchangeability prove again the liveliness and perti- nence of the sixteenth century mannerist painting for Ashbery and his (i.e., our) age. The powerful radiance as Ashbery’s mentor stands in direct contrast to the pity he feels for both Parmigianino the person, and his reduction to a single moment of representation. The two opposite poles of the relationship between poet and portrait and the former’s perception of the latter have now crystallized as Ashbery concomitantly shows admiration for and sympathizes with Parmigianino. 10 Manuel Gasser, Das Selbst bi ldnis. Zürich: K i ndler, 1961, p. 9. 11Peter Weiermair: Introduction. In: Peter Weiermair: Selfportrait als Selbstdarstellung, ed. Gallerie im Taxispalais, Innsbruck: Hörtenbergdruck 1975, n. p. 12John Ashbery: “An Interview By Rose Labrie,” The American Poetry eview May-June 1984: 30. Ashbery points out that Marcel Proust’s mas- terpiece Remembrance of Things Pastis one of his favourite books. It is obvious that he was influenced by the main subject of the book, which is time. Past and present with Parmigianino’s painting and Ashbery’s poem respectively are prevalent themes in SP and in his other works as well. 13Dieter Schmid t, Ich war, ich bin, ich werde sein! Selbstbildnisse deutscher ünstler des 20 . Jahrhunderts. Berlin: Henschel Verlag, 1968, 7. 14Raymond Federman, “Federman on Ferdeman: Lie or Die: Fiction as Autobiography/Autobiography as Fiction,” lecture held at Innsbruck Uni- versity, 26 M arch 1992. The Truth Stripped of Its Abstract Value to Concrete Contingency The Truth Painted into the Portrait While on his odyssey in search for his identity , Ashbery t ra ce s his own split and contradictory character. When compareing Parmigianino and himself he has comes to realize and affirm the paradox of stasis vs. dynamics, prevalence vs temporality. “Lie or Die,”14 as Federman entitled his seminal lecture on Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 67  R. BENEDIKTER ET AL. autobiography held almost two decades ago at Innsbruck Uni- versity which can be extrapolated to address self-portraiture in painting. Lying, defined in the broadest and most abstract way, means not to tell the truth or not to tell the entire truth, to distort by being restrictive. Specifically speaking, by being reductive Parmigianino’s portrait does not tell the whole truth, but only a “bizzaria”. Sydney Freedberg, in his work Parmigianino says of it: “Realism in this portrait No longer produces an objective truth, but a bizzaria…. However its distortion does not create A feeling of disharmony” (73) As such and exclusively as such it lives on. The divergence between image and reality simultaneously distorts and sums up the artist’s life and presents itself to the spectator regardless of time and generation; The record of what you accomplished by sitting down “With great art to copy all that you saw in the glass” So as to perfect and rule out the extraneous Forever. In the circle of your intentions certain spars Remain that perpetuate the enchantment of self with self: Eyebeams, muslin, coral. It doesn’t matter Because these are things as they are today Before one’s shadow ever grew Out of the field into thoughts of tomorrow. (72) The objective truth is stripped of its meaning in favour of the forms which take precedence over the content (cf. Mannerism) and yet communicate t h eir own tenor, Like a wave breaking on a rock, giving up Its shape in a gesture which expresses that shape. The forms retain a strong measure of ideal beauty As they forage in secret on our idea of distortion. (73) Subject and object—that is, painter and “paintee”—are iden- tified as identicals. Nonetheless, their juxtaposition in one sin- gle equation, decreases its correctness. Therefore, a variable must be added in order to rectify the equation: the subject’s (the artist’s) interpretation of himself. Correspondingly, the “leav- ing-out-business” precedes a long period of reflection and pon- dering in order to control of the artist’s variable such that it can later be substituted by a constant. As a study of a particular ego, of the artist’s personality, the portrait delineates the character per se with its most distinctive particularities and private, indi- vidual features. These must be created, interpreted and analyzed. Once worded and recorded they are used as labels to describe the self-portraitist and thus function as generally accepted con- cepts. Being categorized, the artist’s image adopts a stereotypi- cal tinge; It presents its stereotype again But it is an unfamiliar stereotype, the face Riding at anchor, issued from hazards, soon To accost others, “rather angel than man” (Vasari). (73) At this point the question of sincerity arises and leads back to the distortion and lies involved in self-portraiture. Does vanity play a role in the dialogue between painter and his reflection? To what extent does idealization and the artist’s wish-to-be infiltrate his characterization? And finally, what effect does this wishfulness have on the portrait itself?15 Can it still be taken seriously at all, or is it to be dismissed as mere sham and “fig- ment”? A portrait always has a double function. First it is an art genre and as such has representational intent. Representation is solely public, primarily focusing on the physical projection of the artist’s appearance. The physiognomy aids the beholder’s memory, whereas the counterpart reveals the self-portraiture as a means of a purely private purpose: an intimate confession of the artist’s inner desires. Yet, the observant eye can also sense and trace these intimacies. Whispers of the crowd that can’t be understood But can be felt, a chill, a blight Moving outward along the capes and penpinsulas Of your nervures and so to the archipelagos And to the bathed, aired secrecy of the open sea. (75) When seen from this dual aspect perspective, the distortion- as-interpretation derived from, and provided by the artist him- self can be considered to augment the meaningfulness, value and relevance of the self-portrait as a work of art, since, Aping naturalness may be the first step Toward achieving an inner calm But the first step only, and often Remains a frozen gesture of welcome etched On the air materializing behind it, A convention. and we have really No time for these, except to use them For kindling. The sooner they are burnt up The better for the roles we have to play. (82) The Truth Implanted in the Individual Each person Has one big theory to explain the universe But it doesn’t tell the whole story And in the end it is what is outside him That matters, to him and especially to us Who have been given no help whatever In decoding our won man-size quotient and must rely On second-hand knowledge. (81-82) Each person can only have a restricted knowledge of life and of the universe, preconditioned by his/her self, composed of genetic information and environmental influences. “What de- fines the human is this process of surrounding the world with meaning”16 and his/her “concentric growing up of days/Around a life.” (76) Each and all of these circles that expand and enrich one particular life are unique, even though they overlap and intersect with the rings of other lives. Such interconnections build up the universe as a network, in which each knot is an individual life, containing a partial truth, “portions” and “slivers” of the whole. No one and nothing is endowed with the absolute truth, “What is beautiful seems so only in relation to a specific/Life” (77, emphasis by J. H. and R. B.). The entanglement and connection with the whole struc- ture makes possible shared experiences and knowledge. As a consequence of the principle of individuation,each day of one specific life becomes singular, personal and unrepeatable. The vacancies of one day are filled with an incomprehensible amount 15Manuel Gasser 1961, 14. 16Klinkowitz 1988, 130. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 68  R. BENEDIKTER ET AL. of interpretations and meanings. Today has that special, lapidary Todayness that the sunlight reproduces Faithfully in casting twig-shadows on blithe Sidewalks. No previous day would have been like this. (78) Ashbery rejects the notion of universal comprehensibility, because we all tune into our own present, into our own reality. We cannot help being ego-centric and relating what surrounds us to ourselves. Only in doing so can we comprehend and ex- plain the world, in shaping it to our needs and horizon of ex- perience. I used to think they were all alike, That the present always looked the same to everybody But this confusion drains away as one Is always cresting into one’s present. (78) The Portrait as a Symbol The Portrait as Source and Inspiration Parmigianino’s “Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror” is the main source for the poem with the identical title. The insertion of the painting and its criticism into the poetic discourse initi- ates and contributes to the flow of Ashbery’s thoughts. Igniting his reflections, Parmigianino also presents the vehicle that car- ries the poet through his odyssey of self-exploration and self- knowledge. Meditating on Parmigianino’s self, Ashbery’s con- sciousness moves to a contemplation of his own life to a con- sideration of the nature of poetic and pictorial representation and back to the painting once again, where the meditation starts anew.17 The journey on which Ashb e ry goes, Rome where Francesco Was at work during the Sack… … Vienna where the painting is today… … New York Where I am now… (75) And thus draws a circle enclosing all contradictions of his life, similar to the round painting that encircles Parmigianino. The Circular Shape There are two ways that the circle becomes symbolic for the painting and as a consequence for the poem: one, which is re- strictive, and the other that represents continuity. Restriction First, the roundness of the painting, which is actually a spherical segment, geometrically speaking, stands for the glo be with its boundaries. The gravitational field and force of the earth ties us to its surface, restricting life to stay within its con- finements. But it is life englobed. One would like to stick one’s hand Out of the globe, but its dimension, What carries it, will not allow it. … There is no way To build it flat like a section of wall: I must join the segment of a circle. (69) As a symbol the painting, the wooden globe, acquires uni- versal meaning, reminding us of our limitations, and therefore radiating a sad and melancholic mood. One feels too confined, Sifting the April sunlight for clues, In the mere stillness of the ease of its Parameter. the hand holds no chalk And each part of the whole falls off And cannot know it knew, except Here and there, in cold pockets Of rememberance , whispers out of time. (83) Continuity Second, the circularity epitomizes continuity, since it neither marks a beginning nor an end. This is the image of the earth with its life-giving and progressive characteristics. The rotation of the earth around its axis, as well as its orbital course around the sun are emblematic of this universal perpetuity. The the daily succession of day and night, the recurring cycle of the seasons, have a calming effect upon life, giving the sense of stability, “The whole is stable within/Instability… and… changes are merely/Features of the whole.” (70) And yet, the stabilizing continuum is not one-dimensional in its effect. Synchronically to the subduing influence it equivocally makes us aware of time and its passing. The seasons change and these change the weather, “which in French is/Le temps, the word for time.” (70) Movement is bound to time which is tem- porary, flowing “like an hourglass.” (73) Moments are fleeting never to return again. The waterwheel also represents timelessness and eternity, and at the same time temporariness and transience: Hasn’t it too its lair In the present we are always escaping from And falling back into, as the waterwheel of days Pursues its uneventful, even serene course? (79) We are reminded of today, of that particula r moment in time that ceases in favour of the next, which again has to give way for the consecutive instant. We live from one particular moment to the next. Our days are organized, divided into periods, since “we must get out of it even as the public/Is pushing through the museum now so as to/Be out by closing time.” (79) Continuity Disrupted by Mirror-Opposites Nonetheless, ambiguity and contradiction infiltrate such a single hypothesis. Being a child of the postmodern period of contradiction and opposition, Ashbery in his thinking and writ- ing is branded by a dialectical and antithetic argumentation. Not only is today planned and transparent, but it is often veiled and incomprehensible, bec a us e it i s unknown. …today is uncharted, 17Richard Stamelman, “Critical Reflections: Poetry and Art Criticism in Ashbery’s ‘Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror’,” ew Literary History: A ournal of Theory and Interpretation 15.3 (1984): 607. … Today has no margins, the event arrives Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 69  R. BENEDIKTER ET AL. Flush with its edges, is of the same substance. Indistinguishable. (72…79) The ambiguity is raised to a further level, when Ashbery in- troduces the day after today—tomorrow—and claims that Tomorrow is easy, but today is uncharted, Desolate, reluctant as any landscape To yield what are laws of perspective After all only to the painter’s deep Mistrust, a weak instrument though Necessary. (72) Due to the physical law of rotary motion of the earth, every today passes into yesterday where “you can’t live.” The gray glaze of the past attacks all know-how: Secrets of wash and finish that took a lifetime To learn and are reduced to the status of Black-and-white illustrations in a book where colorplates Are rare. (79) Consistently every tomorrow is outstripped by today. As a result, the properties of the chronological succession of days can be regarded in reverse order. Ashbery’s original words swap places: Today is easy, but tomorrow is uncharted, because “Today has that special, lapidary/Todayness,” is unique and therefore easy and pleas ant. Stating one thing and then inverting it to look at it from various perspectives, “We have surprised him/At work, but no, he has surprised us/As he works,” (74) until finally its comple x structure becomes visible and displays its antitheses, like two opposing poles mutually attracting each other to form a unity, without one excluding the other, is a favourite technique used by postmodernists. The network theory is extended to the idea of knots them- selves, as being “resumed within.” In this way the knots can be pictured as atoms with their inner structure. What seems to “take place at random” (76) does not happen arbitrarily, but “in an orderly way, “based on stringent laws, and… things do get done in this way.” (80) Like the concentric progression of days, this argument leads to the assertion that all contrasts are mere appearance, with all oppositions existing only in relation to their counterparts, through which they are perforce dissolved, “the one pole becoming indistinguishable from the other.”18 The principle of polarity is balanced, and made realtive by the principle of complementarity. Painting and Poem Juxtaposition We have by now sensed the liveliness, the moving back and forth, up and down, inside out and outside in of Ashbery’s body of thoughts in this poem. The work abounds with a kinetic en- ergy, moving from one point to the next, from one thought to innumerable associations and counter-associations; time and moment are key words. The present alternates with flashbacks to and from the past, which are actualized as being in the present and then dropped again as being in the past. As already men- tioned, a characteristic feature of movement is that it presup- poses time as a medium. The unities of the fourth dimension— the moments—are transitory. Time is irreversible, and ac- cordingly its content ceases to exit. Today has no margins, the event arrives Flush with its edges, is of the same substance. indistinguishable. (79) Being so indistinguishably connected, time and event also depart together. Not only is this poem regarded as temporal, but so literature in general. It is read sequentially from the beginning to the end, even if the pagination, for instance, is applied in reverse or- der.19 “Words and consciousness enjoy a rare and short-lived intimacy,”20 whereas the visual arts are categorized as being atemporal, they exis t regardless of sequence and time. According to Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, a German poet of Enlightenment, painting and sculpture are subject to a spatial principle.21 This augments the work of art with a prevailing and lasting quality, but reduces it to a rigid and immobile object. Consequently, the two different means of artistic expression, language and visual arts, have their own individual criterion for judgement and criticism. Dynamism or stasis is attributed to one at the cost of the other. Nevertheless, the two standards of judgement typical of distinction types of art are not mutually exclusive. All values with opposing signs can be neutralized on the next higher ring of concentric circles. Exphrastic Unification To overcome this dilemma of dynamism vs stasis, literature picks up an object of art and integrates it within the substance and focus of literary discourse. Through the espousal of the two different art media, the fusion of the two seemingly contrasting parameters of time and space is accomplished. Two dissimilar semiotic systems—picture and language—merge. This rhetoric device where literature incorporates the description of a mute artefact is termed ekphrasis. Tom Mitchell defines it as “a ver- bal representation of visual representation.”22 By employing rhetorical devices in the poem, the portrait’s “will to endure” is transferred to Ashbery’s own portrait, to his text’s will to endure, “its desire to escape the pervasiveness of temporal contingency.”23 The poem’s temporal, unrepeatable flow is stilled by the spatial component of the painting. The spatial work freezes the temporal work and transforms its fleet- ing nature into a permanent quality. Conversely, the painting undergoes a metamorphosis through the dynamics of language. The mute portrait presenting Parmigianino, “speaks out” in the literal sense of the Greek word ekphrasis. It speaks through the verbal depiction of the painting in the poem. Parmigianino is revived; the literary discourse animating his static, enclosed globe. 18Laurence Lieberman, “Unassigned Frequencies: Whispers Out of Time,” The American Poetry Review March-April 1977: 16. 19There are, of course, experimental poems which are structured very visu- ally (e.g. the literary forms of Bildgedicht or Illustrati on). 20Stamelman 1984, 618. 21Murray Krieger, “Ekphrasis and the Still Movement of Poetry; or Laokoon Revisited,” The Poet as Critic, ed. Frederick P. W. McDowell, Evanston: orthwester n UP, 1967, 5. 22W. J. T. M it chell, “Ekphrasis and the Other,” unpu bl ished essay. 23Lee Edelman, “ The Pose of Imposture: Ashbery’s ‘Self-Portrait in a Con- vex Mirror’,” Twentieth Century Literature: A Scholarly and Critical Jour- nal 32.1 (1986): 113. The time of day or the density of the light Adhering to the face keeps it Lively and intact in a recurring wave Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 70  R. BENEDIKTER ET AL. Of arrival. (68) Both the painter’s face and hand, which “retreat[s] slightly…/ Roving back to the body,” and his soul, drift toward and away, “in a recurring wave of arrival.” (69) This oscillating movement, articulated through the temporal medium of language, is essen- tial to defrost Parmigianino’s frozen globe. The coalescence of temporal discourse and spatial work of art is the simultaneous result of stasis and dynamics, an espousal of a couple that gives birth to a unique descendent, a dyad that Krieger has called the “still-movement”.24 Postmodern Techniques Transferred from Painting to Literature Dadaism The first ekphrastic representation was dramatized by Homer in the XVIII book of the Iliad, in which the genesis and ap- pearance of Achilles’ shield, created by the blacksmith god Hephaestus is described.25 Beside the ekphrastic incarnation of Parmigianino, Shakespeare, Mahler, Berg, Hoffman, Vasari and Freedberg become further “percipitates” in Ashbery’s poem, merging into his literary context. His rummaging in the attic of the literary past, the taking down of the most extravagant arte- facts,is reflective of the postmodern spirit. In isolating such unique pieces from their original surrounding, the artist often negates their original purpose and/or function, and gives them a new interpretation. That is to say they acquire an entirely dif- ferent meaning in the postmodern context. Bits and pieces are eclectically selected and pieced together in a collage. The dadaistic technique of cutting and pasting applied to the me- dium of language results in a “verbal collage”26 by means of intertextuality. Similar to Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose —to mention just one example—Ashbery’s poem is rich in allusions to, and selective quotations from earlier fiction or descriptive works. Eco’s The Name of the Rose cites Voltaire, Shakespeare, the Bible and other books. In SP Ashbery quotes Vasari, Freedberg, Berg and Shakespeare. Vasari, “Francesco one day set himself To take his own portrait, looking at himself for that purpose In a convex mirror, such as is used by barbers… He accordingly caused a ball of wood to be made By a tuner, and having divided it in half and Brought it to the size of the mirror, he set himself With great art to copy all that he saw in the glass,” (68) Freedberg, … “Realism in this portrait No longer produces an objective truth, but a biz- zaria…. However its distortion does not create A feeling of disharmony…. The forms retain A strong measure of ideal beauty,” (73) Berg, The locking into place is “death itself,” (76) Or, to quote Imogen in Cymbaline, There cannot Be a pinch in death more sharp than this” (76) These fragments are borrowed from exterior texts and are extracted from their original surrounding, only to be fully inte- grated in a novel milieu, where they serve a newly adopted function, namely Ashbery’s reflection in his self-seeking proc- ess. These borrowed pieces are smoothly blended and yet they retain a loose structure. Moreover, not only do the importations have fragmentary character, but the whole poem is composed of such fragments, jumping from association to association, from connotation to connotation, from painting to poem, from Par- migianino to Ashbery, and vice versa. The poem’s message cannot be isolated or restricted to a single or absolute definition. Its de-centered structure, open-ended constitution and disconti- nuity in the flux of thought transform the poem to a sheer chal- lenge for both the art critic, and for the postmodern-minded reader in general. Its complexity and abundance of topics and countertopics account for divergent interpretations or—per- haps more accurately—attempts at interpretation. Rejecting the idea of a single style or a single truth, the artist of the postmodern age champions the richness, rather than the clarity of meaning. The multiplicity of meaning and truth un- dermines reality, homogenizes incongruities, and at the same time contributes to the complexity and diversity of the being. Art is dressed in the latest style which paradoxically consists of an assemblance and conglomerate of historicist garments, “it carries/The moment of a conviction that had been building,” (76-77) in the course of history, and the “conviction” of our age and its Zeitgeist. The endorsement of pluralism, opulence and classical grandeur is the embodiment of “the cumulative wis- dom and sagacity of a legion of forerunners.”27 The postmodern soil in which the accumulation flourishes “like a rose cabbage” (73) also fertilizes Ashbery, who, for his part, irrigates the ground in return with his own individual, personal style as an artist. It is a giving and taking, a cross- fertilization, and thus a cultivation of new species of valuable works of art. SP is one of the hybrids that grew out of the metaphorical gene pool from which postmodern literary style evolved, and since it was written, Ashbery’s poem has consis- tently been seen as having potential to further evolve the genre. Action Painting Fragmentation of thoughts and content is not the only post- modern element of the poem. The form too, or rather the proc- ess of creating the form is typical of an epoch which despite 9/11 and the subsequent paradigmatic changes (including the “return of essence” and the global “renaissance of religion”) is still contemporary. In an interview with Ross Labrie, Ashbery comments on his act of writing, 24Murray Krieger 1967, 5ff. 25Mario Klarer, “Die Amalgamierung von Zeichensystemen: Ekphrasis, Pronography und alchimische Suche,” Semantische Berichte 1992, spring edition. 26Philip Stevick, “Literature,” The Postmodern Moment: A Handbook o Contemporary Innovation in the Arts, ed. Stanley Trachtenberg, Westport: Greenwood Press, 1985, 144. 27Laurence Lieberman 1977, 17. 28John Ashbery, “John Ashbery: An Interview by Ross Labrie,” The Ameri- can Poetry Review, May-June 1984: 30. … my poetry is not a poetry of ideas treated in a regular, prosodical way… I don’t know what the content of my po- ems is or what their form is either. It seems to be a question which doesn’t exist for me. I begin writing without knowing what I’m thinking, and stop once I feel I’ve finished. The form seems to be the content and vice versa for me.28 This method of creating literature is subject to the moment of Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 71  R. BENEDIKTER ET AL. the writing process, and therefore is influenced by the author’s psychological state, his mood at the time of writing, as well as by the physical surrounding that affect his literary work. As Ashbery has noted, Whatever things are on my desk or in the room or outside the window seem to get sucked into the poem as though a vac- uum cleaner was at work.29 The genesis of the poem, its “act of creation”, thus becomes extremely important. This always Happens, as in the game where A whispered phrase passed around the room Ends up as something completely different. It is the principle that makes works of art so unlike What the artist intended. Often he finds He has omitted the thing he started out to say In the first place. Seduced by flowers, Explicit pleasures, he blames himself (though Secretly satisfied with the result), imagining He had a say in the matter and exercised An option of which he was hardly conscious, Unaware that necessity circumvents such resolutions. So as to create something new For itself, that there is no other way, That the history of creation proceeds according to Stringent laws, and that things We set out to accomplish and wanted so desperately To see come into being. (80) This particular technique of producing a work of art, with its unknown outcome, its development and evolutionary coming into existence is rooted in the concept of Action Painting, a term coined by the American poet and critic Harold Rosenberg. 30 “With the intention becoming less important than the sur- prise,”31 the act of painting outweighs the importance of the finished painting. The gesture on the canvas becomes an act of liberation, and so does the procedure of writing. The paper that records the flow of thoughts that seeps through the mental sieve is analogous to the dripping technique used by Jackson Pollock, to whom Rosenberg principally refers. What seems to be wholly random, as far as such dripping is concerned, can be influenced and manipulated by the artist’s will and wish. He can decide upon the colours and their com- bination. Additionally, he can define the size of the holes in the receptacle, through which the colour is to drop or flow. Like- wise, Ashbery does not surrender to his own mental conquest of connotations, I don’t think that my poetry is completely free association. There is a sort of monitoring or editing activity that goes on as I’m writing, merely because I don’t want to get too far from what other people’s free association might be, but in- stead in a way to echo them, and I hope, illuminate them. That’s why, although I’m frequently accused of being a very private poet, I don’t write about my own private experiences very much, but try to write about paradigms of common ex- periences which I hope other people can share.32 Conclusion The multiplicity and complexity of Ashbery’s poem “Self- portrait in a Convex Mirror” is not only due to its treatment and dramatization of a variety of subjects, but also to their structure. They overlap and interfere with each other and thus make a linear discussion impossible. The tackling of art within art takes such complexity steps further. Like an endless set of Chinese boxes, each step opens up new vistas, and contains a variety of new items and new surprises. The comparison of two self-portraits, expressed using two different artistic means with one finding itself in and identifying with the other, yet after a while rejecting it again as self-image, gives rise to an abundance of movement and action in the course of the poem. However, activity and movement do not follow the principle of linearity. Instead, the poem is character- ized by discontinuity, disruption and fragmentation. Both the painting and the poem are fragments. Parmigianino is deflated to a surface existence upon his easel, his body reduced to his head, bust and hand, the latter colossally depicted a nd hel d up to fulfil an equivocal purpose of both inviting and keeping the beholder at a distance. One function being reversed to its opposite, its counter-function a 180 degree mirror image, in one and the same moment becomes indistinguishable from its deri- vation. Thus unified, all opposites and oppositions become equal, although they do not give up their original characteristic. Correla- tion is the key to their concomitantly intrinsic and extrinsic na- ture. Being inwardly complete, furnished with their own inte- gral qualities, they also serve an outer function. Their comple- tion is heightened through the harmonization of their inward and outward complementarity. The fragments in the poem range from a variety of subject splinters and quotations of art criticism, and from narrative elements to an alternation between painting and poem, Par- migianino an d Ashbery, past and present, spa tiality and tempo- rality, all of which amalgamate within Ashbery’s masterpiece. This fragmentation is eventually extended to a philosophy of life. The universe itself is built up of “sawtoothed garments.” Human beings, seen as parts, “clumps of crystal,” are bound to their individual knowledge and experience, and as a result, are restricted in their possibilities and limited in their action. How- ever, life is open-ended like the poem, and the concentric ad- vancement of days permanently expand a life, broadens its horizon and endows it with new experiences. And this, in essence, is the life of the post-modern mind itself in our times. Acknowledgements The authors gratefully acknowledge the intellectual contribu- tion and review of Prof. Dr. James Giordano, University of Oxford, UK, on an initial version of this essay. 29ibid. 32. 30Harold Rosenberg, “The Anxious Object: Art Today and its Audience,” rt News September 1952; excerpt in Art of Our Century: the Chronicle o Western Art: 1900 to the Present, 1988, trans. Walter D. Glanze, ed. Jean- Louis Ferrier, New York, London et. al.: Prentice Hall 1989, 491. 31Klinkowitz 1988, 123. 32John Ashbery 1984, 31. REFERENCES Ashbery, J. (1975). Self-portrait in a convex mirror. New York: The Viking Press. 68-83. Ashbery, J. (1984). John Ashbery: An interview by Ross Labrie. The American Poetry Review, 13, 29-33. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 72  R. BENEDIKTER ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 73 Brinkhus, G. (Ed.) (1989). Selbst-bildnisse im spiegel einer sammlung. Ausstellungskataloge der Universität Tübingen 22. Tübingen: At- tempto. Davidson, M. (1983). Ekphrasis and the postmodern painter poem. Journal of Aesthetics and Art Cr i t icism, 42, 69-79. doi:10.2307/429948 Edelman, L. (1986). The pose of imposture: Asbhery’s “self-portrait in a convex mirror”. Twentieth Century Literature: A Scholarly and Critical Journal, 32, 95-114. Ferrier, J.-L. (Ed.) (1989). Art of our century: The chronicle of western art: 1900 to the present 1988. New York: Prentice Hall. Freedberg, S. J. (1971). Parmigianino: His works in painting. Westport: Conn. Fröhlich-Blum, L. (1921). Parmigianino und der manierismus. Wien: Anton Scholl. Gasser, M. (1961). Das selbstbildnis. Zürich: Kindler. Ghidiglia Quintavalle, A. (1964). Parmigianino. I maestri del colore 24. Milano: Fratelli Fabbri. Klarer, M. (1992). Die Amalgamierung von Zeichensystemen: Ekphra- sis, Pornographie und alchimische Suche. Semantische Berichte, Spring edition. Klarer, M. (2003). Ekphrasis. Literary descriptions of pieces of visual art in texts by Spenser, Sidney, Lyly, and Shakespeare. Horst Wein- stock, English and American Studies in German. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. Klinkowitz, J. (1988). Rosenberg, Barthes, Hassan: The postmodern habit of thought. Athens: Georgia University Press. Krieger, M. (1967). Ekphrasis and the still movement of poetry; or, Laokoon revisited. In P. W. Frederick (Ed.), The poet as critic (pp. 3-26). McDowell, Evanston: Northwestern University Press. Lieberman, L. (1977). Unassigned frequencies: Whispers out of time. The American Poetry Review March-April 1977, 4-18. Mitchell, W. J. T (1979). On poems on pictures: Ekphrasis and the other. Unpublished essay. Molesworth, C. (1979). The fierce embrace: A study of contemporary American poetry. Columbia and London: Missouri University Press. Nietzsche, F. (1956). “The birth of tragedy” and “the genealogy of morals”. New York: Doubleday Anchor Press. Rawson, C. (1986). A poet in the postmodern playground. Times Liter- ary Supplement, 723-724. Rossi, P. (1980). L’opera completa del Parmigianino. Classici dell’Arte 101. Milano: Rizzoli. Schmidt, D. (1986). Ich war, ich bin, ich werde sein! Selbstbildnisse deutscher Künstler des 20. Jahrhunderts. Berlin: Henschelverlag. Stamelman, R. (1984). Critical reflections: Poetry and art criticism in Asbhery’s ‘self-portrait in a convex mirror’. New Literary History: A Journal of Theory and Interpretation, 15, 607-630. Vasari, G. (1988). Leben der ausgezeichnetsten Maler, Bildhauer und Baumeister; Von Cimabue bis zum Jahre 1567. In J. Kliemann (Ed.), L. Schorn and E. Förster (Trans.). Worms: Werner’sche Verlagsge- sellschaft. 1832-1849. Stevick, P. (1985). Literature. In S. Trachtenberg (Ed.), The postmod- ern moment: A handbook of contemporary innovation in the arts (pp. 135-156). Westport: Greenwood Press. Vendler, H. (1988). The music of what happens: Poems, poets, critics. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. Weiermair, P. (1975). Selbstportrait als selbstdarstellung. Innsbruck: Hörtenbergdruck. Wordsworth, W., & Samuel T. C. (1987). Lyrical ballads (3rd ed.). Plymouth: Northcote House. 1805.

|