J. MCKNIGHT ET AL.

while 20% were 19 years old. The average age of respondents

was 23 (M = 23.36, SD = 8.53). The ages represented in the

sample ranged from 18 to 66. The largest percentage of student

participants was 18 years old, or 27%, with 19 year olds rank-

ing 20%. There were ten student participants, or 8%, who did

not wish to report their age.

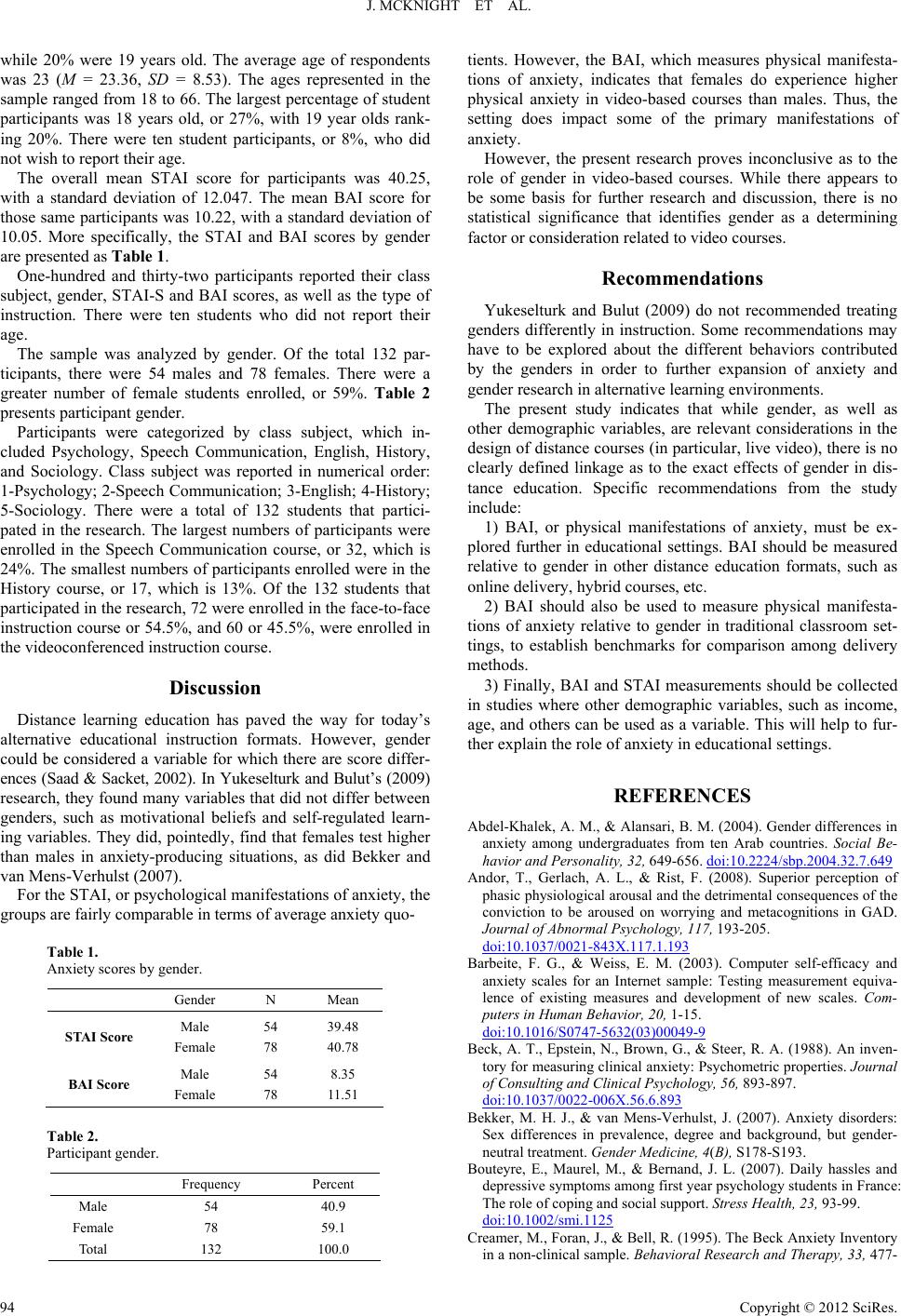

The overall mean STAI score for participants was 40.25,

with a standard deviation of 12.047. The mean BAI score for

those same participants was 10.22, with a standard deviation of

10.05. More specifically, the STAI and BAI scores by gender

are presented as Table 1.

One-hundred and thirty-two participants reported their class

subject, gender, STAI-S and BAI scores, as well as the type of

instruction. There were ten students who did not report their

age.

The sample was analyzed by gender. Of the total 132 par-

ticipants, there were 54 males and 78 females. There were a

greater number of female students enrolled, or 59%. Table 2

presents participant gender.

Participants were categorized by class subject, which in-

cluded Psychology, Speech Communication, English, History,

and Sociology. Class subject was reported in numerical order:

1-Psychology; 2-Speech Communication; 3-English; 4-History;

5-Sociology. There were a total of 132 students that partici-

pated in the research. The largest numbers of participants were

enrolled in the Speech Communication course, or 32, which is

24%. The smallest numbers of participants enrolled were in the

History course, or 17, which is 13%. Of the 132 students that

participated in the research, 72 were enrolled in the face-to-face

instruction course or 54.5%, and 60 or 45.5%, were enrolled in

the videoconferenced instruction course.

Discussion

Distance learning education has paved the way for today’s

alternative educational instruction formats. However, gender

could be considered a variable for which there are score differ-

ences (Saad & Sacket, 2002). In Yuke selturk and Bulut’s (2009)

research, they found many variables that did not differ between

genders, such as motivational beliefs and self-regulated learn-

ing variables. They did, pointedly, find that females test higher

than males in anxiety-producing situations, as did Bekker and

van Mens-Verhulst (2007).

For the STAI, or psychological manifestations of anxiety, the

groups are fairly comparable in terms of average anxiety quo-

Table 1.

Anxiety scores by gender.

Gender N Mean

STAI Score Male

Female

54

78

39.48

40.78

BAI Score Male

Female

54

78

8.35

11.51

Table 2.

Participant gender.

Frequency Percent

Male 54 40.9

Female 78 59.1

Total 132 100.0

tients. However, the BAI, which measures physical manifesta-

tions of anxiety, indicates that females do experience higher

physical anxiety in video-based courses than males. Thus, the

setting does impact some of the primary manifestations of

anxiety.

However, the present research proves inconclusive as to the

role of gender in video-based courses. While there appears to

be some basis for further research and discussion, there is no

statistical significance that identifies gender as a determining

factor or consideration related to vid eo cou rses.

Recommendations

Yukeselturk and Bulut (2009) do not recommended treating

genders differently in instruction. Some recommendations may

have to be explored about the different behaviors contributed

by the genders in order to further expansion of anxiety and

gender research in alternative learning environments.

The present study indicates that while gender, as well as

other demographic variables, are relevant considerations in the

design of distance courses (in particular, live video), there is no

clearly defined linkage as to the exact effects of gender in dis-

tance education. Specific recommendations from the study

include:

1) BAI, or physical manifestations of anxiety, must be ex-

plored further in educational settings. BAI should be measured

relative to gender in other distance education formats, such as

online delivery, hybrid courses, etc.

2) BAI should also be used to measure physical manifesta-

tions of anxiety relative to gender in traditional classroom set-

tings, to establish benchmarks for comparison among delivery

methods.

3) Finally, BAI and STAI measurements should be collected

in studies where other demographic variables, such as income,

age, and others can be used as a variable. This will help to fur-

ther explain the role of anxiety in educational set tings.

REFERENCES

Abdel-Khalek, A. M., & Alansari, B. M. (2004). Gender differences in

anxiety among undergraduates from ten Arab countries. Social Be-

havior and Personality, 32, 649-656. doi:10.2224/sbp.2004.32.7.649

Andor, T., Gerlach, A. L., & Rist, F. (2008). Superior perception of

phasic physiological arousal and the detrimental consequences of the

conviction to be aroused on worrying and metacognitions in GAD.

Journal of Abnormal Psycholo gy , 117, 193-205.

doi:10.1037/0021-843X.117.1.193

Barbeite, F. G., & Weiss, E. M. (2003). Computer self-efficacy and

anxiety scales for an Internet sample: Testing measurement equiva-

lence of existing measures and development of new scales. Com-

puters in Human Behavior, 20, 1-15.

doi:10.1016/S0747-5632(03)00049-9

Beck, A. T., Epstein, N., Brown, G., & Steer, R. A. (1988). An inven-

tory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. Journal

of Consulting and Clinical Psychology , 56, 893-897.

doi:10.1037/0022-006X.56.6.893

Bekker, M. H. J., & van Mens-Verhulst, J. (2007). Anxiety disorders:

Sex differences in prevalence, degree and background, but gender-

neutral treatment. Gender Medicine, 4(B), S178-S193.

Bouteyre, E., Maurel, M., & Bernand, J. L. (2007). Daily hassles and

depressive symptoms among first year psychology students in France:

The role of coping and social suppo rt. Stress H e a lth, 23, 93-99.

doi:10.1002/smi.1125

Creamer, M., Foran, J., & Bell, R. (1995). The Beck Anxiety Inventory

in a non-clinical sample. Behavioral Research and Therapy, 33, 477-

Copyright © 2012 SciRes.

94