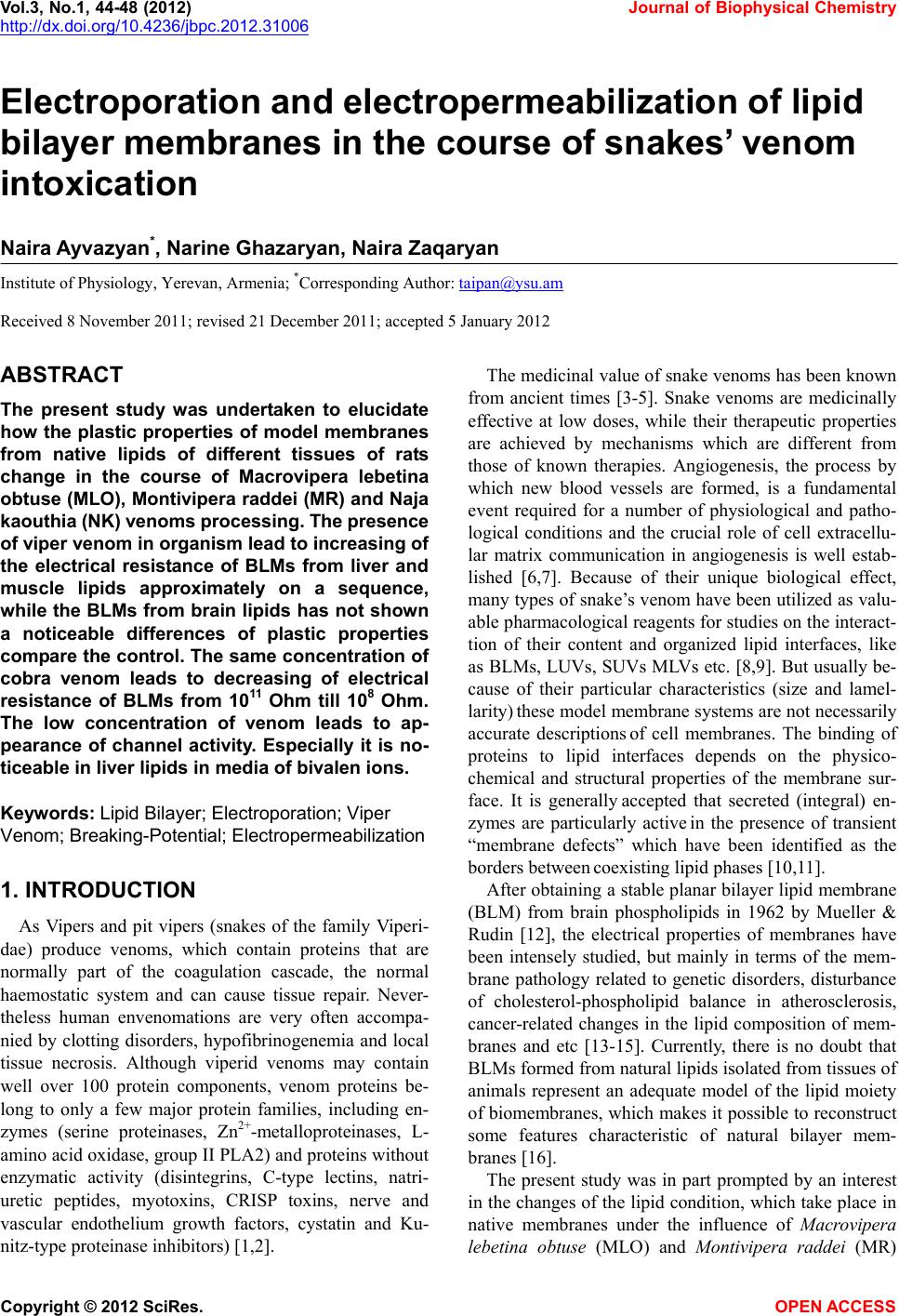

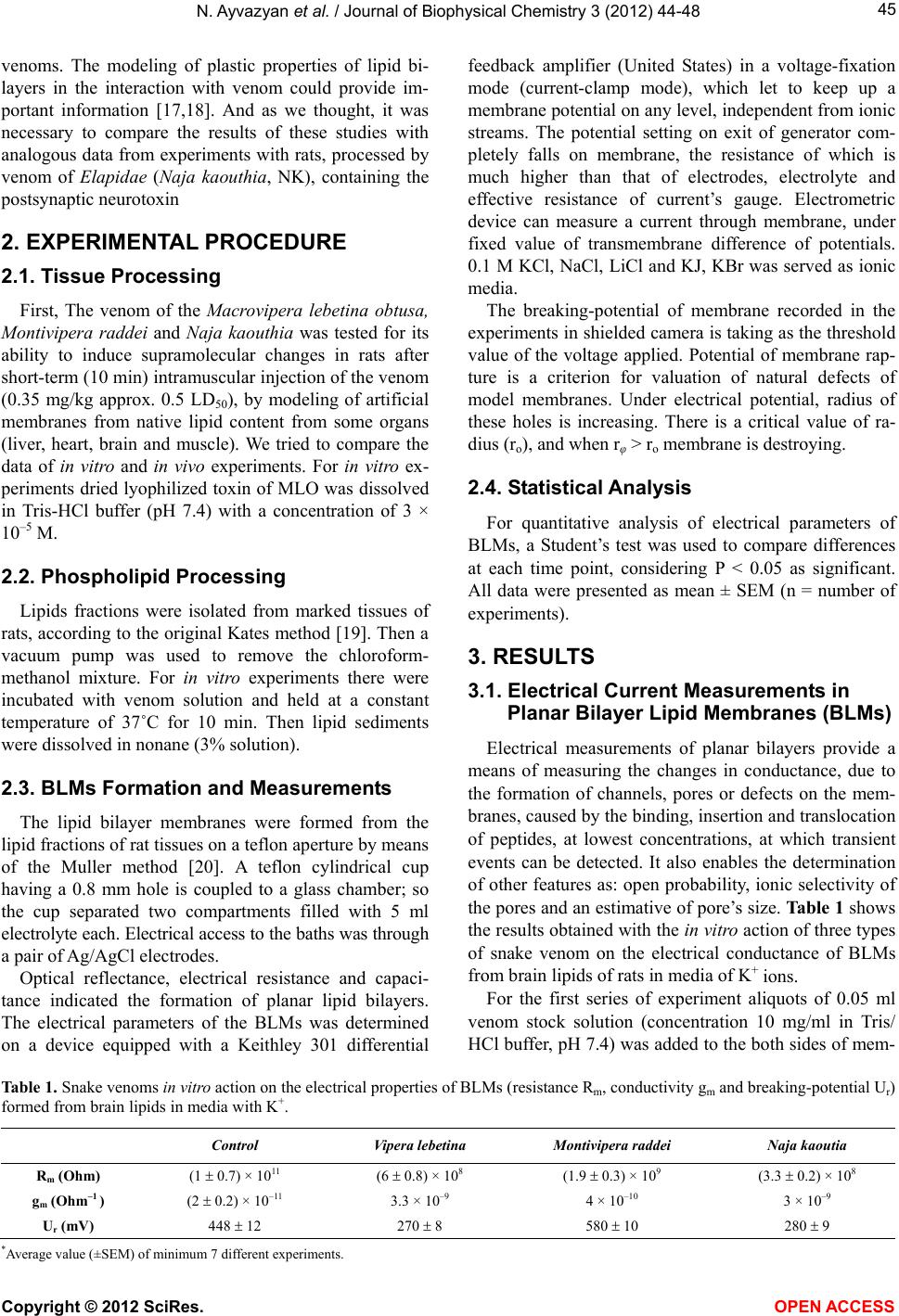

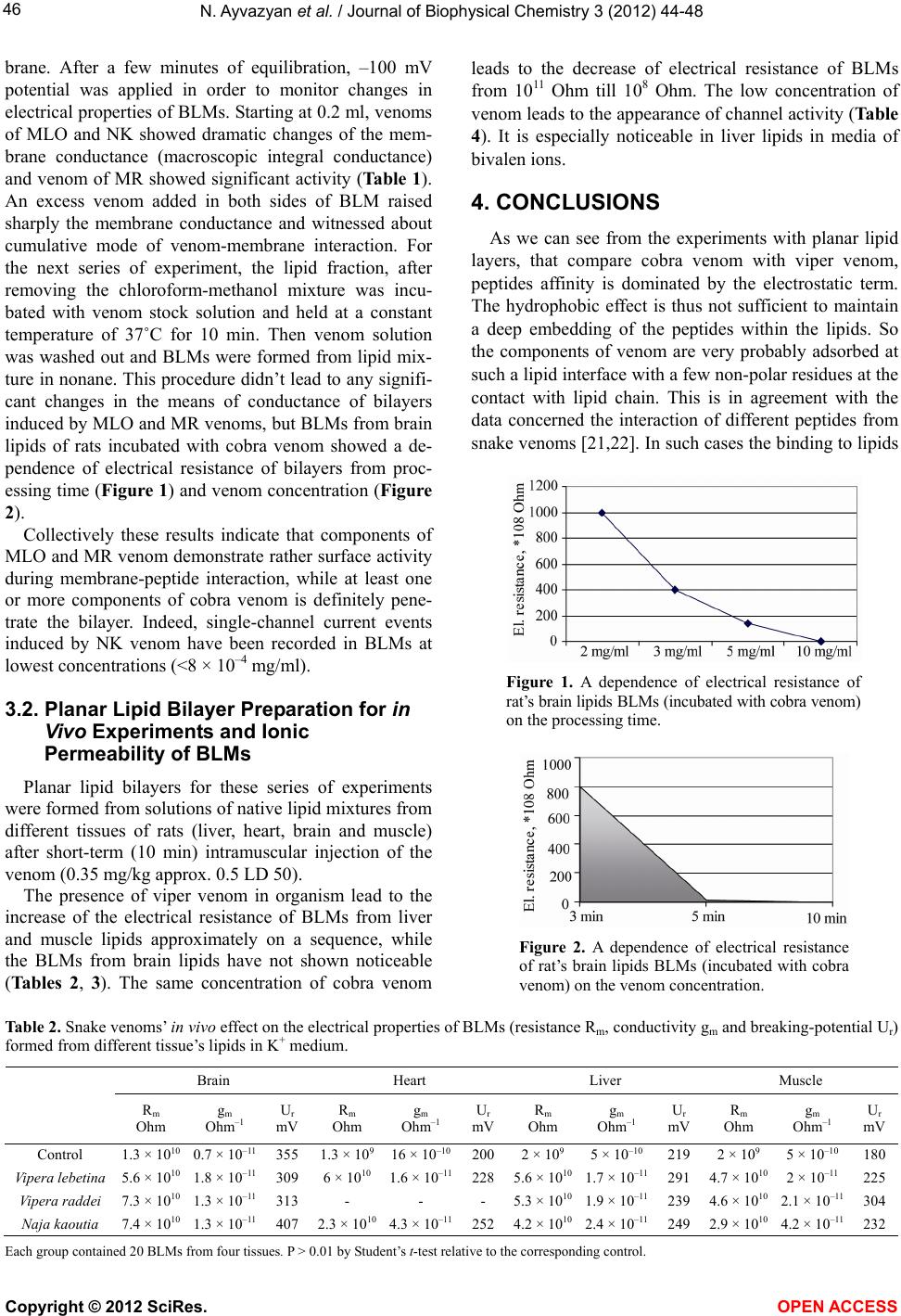

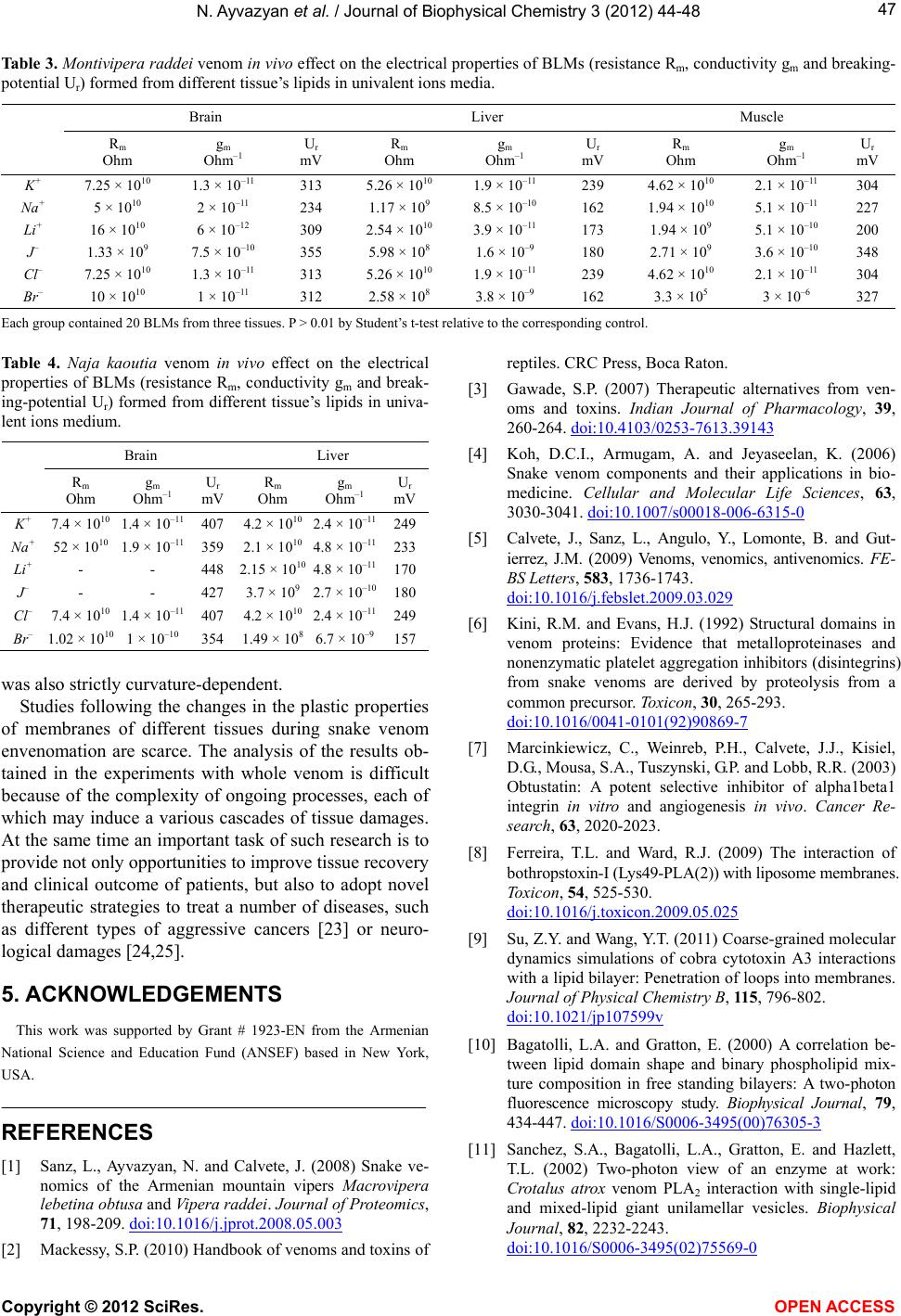

Vol.3, No.1, 44-48 (2012) Journ al of Biophysical Chemistry http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jbpc.2012.31006 Electroporation and electropermeabilization of lipid bilayer membranes in the course of snakes’ venom intoxication Naira A yvazyan*, Narine Ghazaryan, Naira Zaqaryan Institute of Physiology, Yerevan, Armenia; *Corresponding Author: taipan@ysu.am Received 8 November 2011; revised 21 December 2011; accepted 5 January 2012 ABSTRACT The present study was undertaken to elucidate how the plastic properties of model membranes from native lipids of different tissues of rats change in the course of Macrovipera lebetina obtuse (MLO), Montivipera raddei (MR) and Naja kaouthia (NK) venoms processing. T he presence of viper venom in organism lead to increasing of the electrical resistance of BLMs from liver and muscle lipids approximately on a sequence, while the BLMs from brain lipids has not show n a noticeable differences of plastic properties compare the control. The same concentration of cobra venom leads to decreasing of electrical resistance of BLMs from 1011 Ohm till 108 Ohm. The low concentration of venom leads to ap- pearance of channel activity. Especially it is no- ticeable in liver lipids in media of bivalen ions. Keywords: Lipid Bilayer; Electroporation; Viper Venom; Breaking-Potenti al; Electropermeabilization 1. INTRODUCTION As Vipers and pit vipers (snakes of the family Viperi- dae) produce venoms, which contain proteins that are normally part of the coagulation cascade, the normal haemostatic system and can cause tissue repair. Never- theless human envenomations are very often accompa- nied by clotting disorders, hypofibrinogenemia and local tissue necrosis. Although viperid venoms may contain well over 100 protein components, venom proteins be- long to only a few major protein families, including en- zymes (serine proteinases, Zn2+-metalloproteinases, L- amino acid oxidase, gro up II PLA2) and proteins without enzymatic activity (disintegrins, C-type lectins, natri- uretic peptides, myotoxins, CRISP toxins, nerve and vascular endothelium growth factors, cystatin and Ku- nitz-type proteinase inhibitors) [1,2]. The medicinal value of snake venoms has been known from ancient times [3-5]. Snake venoms are medicinally effective at low doses, while their therapeutic properties are achieved by mechanisms which are different from those of known therapies. Angiogenesis, the process by which new blood vessels are formed, is a fundamental event required for a number of physiological and patho- logical conditions and the crucial role of cell extracellu- lar matrix communication in angiogenesis is well estab- lished [6,7]. Because of their unique biological effect, many types of snak e’s venom have been u tilized as valu- able pharmacological reagents for studies on the interact- tion of their content and organized lipid interfaces, like as BLMs, LUVs, SUVs MLVs etc. [8,9]. But usually be- cause of their particular characteristics (size and lamel- larity) these model membrane systems are not necessarily accurate descriptions of cell membranes. The binding of proteins to lipid interfaces depends on the physico- chemical and structural properties of the membrane sur- face. It is generally accepted that secreted (integral) en- zymes are particularly active in the presence of transient “membrane defects” which have been identified as the borders between coexisting lipid phases [10 ,11]. After obtaining a stable planar bilayer lipid membrane (BLM) from brain phospholipids in 1962 by Mueller & Rudin [12], the electrical properties of membranes have been intensely studied, but mainly in terms of the mem- brane pathology related to genetic disorders, disturbance of cholesterol-phospholipid balance in atherosclerosis, cancer-related changes in the lipid composition of mem- branes and etc [13-15]. Currently, there is no doubt that BLMs formed from natural lipids isolated from tissues of animals represent an adequate model of the lipid moiety of biomembranes, which makes it possible to reconstruct some features characteristic of natural bilayer mem- branes [16]. The present study was in part prompted by an interest in the changes of the lipid condition, which take place in native membranes under the influence of Macrovipera lebetina obtuse (MLO) and Montivipera raddei (MR) Copyright © 2012 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  N. Ayvazyan et al. / Journal of Biophysical Chemistry 3 (2012) 44-48 45 venoms. The modeling of plastic properties of lipid bi- layers in the interaction with venom could provide im- portant information [17,18]. And as we thought, it was necessary to compare the results of these studies with analogous data from experiments with rats, processed by venom of Elapidae (Naja kaouthia, NK), containing the postsynapti c n eurotoxin 2. EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURE 2.1. Tissue Processing First, The venom of the Macrovipera lebetina obtusa, Montivipera raddei and Naja kaouthia was tested for its ability to induce supramolecular changes in rats after short-term (10 min) intramuscular injection of the venom (0.35 mg/kg approx. 0.5 LD50), by modeling of artificial membranes from native lipid content from some organs (liver, heart, brain and muscle). We tried to compare the data of in vitro and in vivo experiments. For in vitro ex- periments dried lyophilized toxin of MLO was dissolved in Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4) with a concentration of 3 × 10–5 M. 2.2. Phospholipid Processing Lipids fractions were isolated from marked tissues of rats, according to the original Kates method [19]. Then a vacuum pump was used to remove the chloroform- methanol mixture. For in vitro experiments there were incubated with venom solution and held at a constant temperature of 37˚C for 10 min. Then lipid sediments were dissolved in nonane (3% solution). 2.3. BLMs Formation and Measurements The lipid bilayer membranes were formed from the lipid fractions of rat tissues on a teflon ap ertu re by means of the Muller method [20]. A teflon cylindrical cup having a 0.8 mm hole is coupled to a glass chamber; so the cup separated two compartments filled with 5 ml electrolyte each. Electrical access to the baths was through a pair of Ag/AgCl electrodes. Optical reflectance, electrical resistance and capaci- tance indicated the formation of planar lipid bilayers. The electrical parameters of the BLMs was determined on a device equipped with a Keithley 301 differential feedback amplifier (United States) in a voltage-fixation mode (current-clamp mode), which let to keep up a membrane potential on any level, independent from ionic streams. The potential setting on exit of generator com- pletely falls on membrane, the resistance of which is much higher than that of electrodes, electrolyte and effective resistance of current’s gauge. Electrometric device can measure a current through membrane, under fixed value of transmembrane difference of potentials. 0.1 M KCl, NaCl, LiCl and KJ, KBr was served as ionic media. The breaking-potential of membrane recorded in the experiments in shielded camera is taking as the threshold value of the voltage applied. Potential of membrane rap- ture is a criterion for valuation of natural defects of model membranes. Under electrical potential, radius of these holes is increasing. There is a critical value of ra- dius (ro), an d wh en rφ > ro membrane is destroying. 2.4. Statistical Analysis For quantitative analysis of electrical parameters of BLMs, a Student’s test was used to compare differences at each time point, considering P < 0.05 as significant. All data were presented as mean ± SEM (n = number of experiments). 3. RESULTS 3.1. Electrical Current Measurements in Planar Bilayer Lipid Membranes (BLMs) Electrical measurements of planar bilayers provide a means of measuring the changes in conductance, due to the formation of channels, pores or defects on the mem- branes, caused by the binding, insertion and translocation of peptides, at lowest concentrations, at which transient events can be detected. It also enables the determination of other features as: open probability, ionic selectivity of the pores and an estimative of pore’s size. Table 1 shows the results obtained with the in vitro action of three types of snake venom on the electrical conductance of BLMs from brain lipids of rats in media of K+ ions. For the first series of experiment aliquots of 0.05 ml venom stock solution (concentration 10 mg/ml in Tris/ HCl buffer, pH 7.4) w as added to the both sides of mem- Table 1. Snake venoms in vitro action on the electrical properties of BLMs (resistance Rm, conductivity gm and breaking-potential Ur) formed from brain lipids in media with K+. Control Vipera lebetina Montivipera raddei Naja kaoutia Rm (Ohm) (1 0.7) × 1011 (6 0.8) × 108 (1.9 0.3) × 109 (3.3 0.2) × 108 gm (Ohm–1 ) (2 0.2) × 10–11 3.3 × 10–9 4 × 10–10 3 × 10–9 Ur (mV) 448 12 270 8 580 10 280 9 *Average value (±SEM) of mi ni mum 7 different experiments. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  N. Ayvazyan et al. / Journal of Biophysical Chemistry 3 (2012) 44-48 46 brane. After a few minutes of equilibration, –100 mV potential was applied in order to monitor changes in electrical properties of BLMs. Starting at 0.2 ml, venoms of MLO and NK showed dramatic changes of the mem- brane conductance (macroscopic integral conductance) and venom of MR showed significant activity (Tabl e 1). An excess venom added in both sides of BLM raised sharply the membrane conductance and witnessed about cumulative mode of venom-membrane interaction. For the next series of experiment, the lipid fraction, after removing the chloroform-methanol mixture was incu- bated with venom stock solution and held at a constant temperature of 37˚C for 10 min. Then venom solution was washed out and BLMs were formed from lipid mix- ture in nonane. This procedure didn’t lead to any signifi- cant changes in the means of conductance of bilayers induced by MLO and MR venoms, but BLMs from brain lipids of rats incubated with cobra venom showed a de- pendence of electrical resistance of bilayers from proc- essing time (Figure 1) and venom concentration (Figure 2). Collectively these results indicate that components of MLO and MR venom demonstrate rather surface activity during membrane-peptide interaction, while at least one or more components of cobra venom is definitely pene- trate the bilayer. Indeed, single-channel current events induced by NK venom have been recorded in BLMs at lowest concentrations (<8 × 10–4 mg/ml). 3.2. Planar Lipid Bilayer Preparation for in Vivo Experiments and Ionic Permeability of BLMs Planar lipid bilayers for these series of experiments were formed from solutions of native lipid mixtures from different tissues of rats (liver, heart, brain and muscle) after short-term (10 min) intramuscular injection of the venom (0.35 mg/kg approx. 0.5 LD 50). The presence of viper venom in organism lead to the increase of the electrical resistance of BLMs from liver and muscle lipids approximately on a sequence, while the BLMs from brain lipids have not shown noticeable (Tables 2, 3). The same concentration of cobra venom leads to the decrease of electrical resistance of BLMs from 1011 Ohm till 108 Ohm. The low concentration of venom leads to the app earance of chann el activity (Table 4). It is especially noticeable in liver lipids in media of bivalen ions. 4. CONCLUSIONS As we can see from the experiments with planar lipid layers, that compare cobra venom with viper venom, peptides affinity is dominated by the electrostatic term. The hydrophobic effect is thus not sufficient to maintain a deep embedding of the peptides within the lipids. So the components of venom are very probably adsorbed at such a lipid interface with a few non-polar residues at the contact with lipid chain. This is in agreement with the data concerned the interaction of different peptides from snake venoms [21,22]. In such cases the binding to lipids Figure 1. A dependence of electrical resistance of rat’s brain lipi ds BLMs (incubate d with cobra ven om) on the processing time. Figure 2. A dependence of electrical resistance of rat’s brain lipids BLMs (incubated with cobra venom) on the venom concentration. Table 2. Snake venoms’ in vivo effect on the electrical properties of BLMs (resistance Rm, conductivity gm and breaking-potential Ur) formed from different tissue’s lipids in K+ medium. Brain Heart Liver Muscle Rm Ohm gm Ohm–1 Ur mV Rm Ohm gm Ohm–1 Ur mV Rm Ohm gm Ohm–1 Ur mV Rm Ohm gm Ohm–1 Ur mV Control 1.3 × 1010 0.7 × 10–11 355 1.3 × 10916 × 10–10 2002 × 1095 × 10–10 219 2 × 109 5 × 10–10180 Vipera lebetina 5.6 × 1010 1.8 × 10–11 309 6 × 1010 1.6 × 10–11 2285.6 × 1010 1.7 × 10–11 291 4.7 × 1010 2 × 10–11 225 Vipera raddei 7.3 × 1 010 1.3 × 10–11 313 - - - 5.3 × 1010 1.9 × 10–11 239 4.6 × 1010 2.1 × 10–11304 Naja kaoutia 7.4 × 1010 1.3 × 10–11 407 2.3 × 1010 4.3 × 10–11 2524.2 × 1010 2.4 × 1 0–11 249 2.9 × 1010 4.2 × 10–11232 Each group contained 20 BLMs from four tissues. P > 0.01 by Stu dent’s t-test relative to the corre sponding control. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  N. Ayvazyan et al. / Journal of Biophysical Chemistry 3 (2012) 44-48 47 Table 3. Montivipera raddei venom in vivo effect on the electrical properties of BLMs (resistance Rm, conductivity gm and breaking- potential Ur) formed from different tissue’s lipids in univalent ions media. Brain Liver Muscle Rm Ohm gm Ohm–1 Ur mV Rm Ohm gm Ohm–1 Ur mV Rm Ohm gm Ohm–1 Ur mV K+ 7.25 × 1010 1.3 × 10–11 313 5.26 × 1010 1.9 × 10–11 239 4.62 × 1010 2.1 × 10–11 304 Na+ 5 × 1010 2 × 10–11 234 1.17 × 109 8.5 × 10–10 162 1.94 × 1010 5.1 × 10–11 227 Li+ 16 × 1010 6 × 10–12 309 2.54 × 1010 3.9 × 10–11 173 1.9 4 × 109 5.1 × 10–10 200 J– 1.33 × 109 7.5 × 10–10 355 5.98 × 108 1.6 × 10–9 180 2.71 × 109 3. 6 × 1 0–10 348 Cl– 7.25 × 1 010 1.3 × 10–11 313 5.26 × 1010 1.9 × 10–11 239 4.62 × 1010 2.1 × 10–11 304 Br– 10 × 1010 1 × 10–11 312 2.58 × 108 3.8 × 10–9 162 3.3 × 105 3 × 10–6 327 Each group contained 2 0 BLMs from th ree tissues. P > 0.01 by S tudent’s t-test re l ative to the c orr esponding control. Table 4. Naja kaoutia venom in vivo effect on the electrical properties of BLMs (resistance Rm, conductivity gm and break- ing-potential Ur) formed from different tissue’s lipids in univa- lent ions medium. Brain Liver Rm Ohm gm Ohm–1 Ur mV Rm Ohm gm Ohm–1 Ur mV K+ 7.4 × 1010 1.4 × 10–11 4074.2 × 1010 2.4 × 10–11 249 Na+ 52 × 1010 1.9 × 10–11 3592.1 × 1010 4.8 × 10–11 233 Li+ - - 4482.15 × 1010 4.8 × 10–11 170 J– - - 4273.7 × 109 2.7 × 10–10 180 Cl– 7.4 × 1010 1.4 × 10–11 4074.2 × 1010 2.4 × 10–11 249 Br– 1.02 × 1010 1 × 10–10 3541.49 × 108 6.7 × 10–9 157 was also strictly curvature-dependent. Studies following the changes in the plastic properties of membranes of different tissues during snake venom envenomation are scarce. The analysis of the results ob- tained in the experiments with whole venom is difficult because of the complexity of ongoing processes, each of which may induce a various cascades of tissue damages. At the same time an important task of su ch research is to provide not only opportunities to improv e tissue recov ery and clinical outcome of patients, but also to adopt novel therapeutic strategies to treat a number of diseases, such as different types of aggressive cancers [23] or neuro- logical damages [24,25]. 5. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This work was supported by Grant # 1923-EN from the Armenian National Science and Education Fund (ANSEF) based in New York, USA. REFERENCES [1] Sanz, L., Ayvazyan, N. and Calvete, J. (2008) Snake ve- nomics of the Armenian mountain vipers Macrovipera lebetina obtusa and Vipera raddei. Journal of Proteomics, 71, 198-209. doi:10.1016/j.jprot.2008.05.003 [2] Mackessy, S.P. (2010) Handbook of venoms and toxins of reptiles. CRC Press, Boca Raton. [3] Gawade, S.P. (2007) Therapeutic alternatives from ven- oms and toxins. Indian Journal of Pharmacology, 39, 260-264. doi:10.4103/0253-7613.39143 [4] Koh, D.C.I., Armugam, A. and Jeyaseelan, K. (2006) Snake venom components and their applications in bio- medicine. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 63, 3030-3041. doi:10.1007/s00018-006-6315-0 [5] Calvete, J., Sanz, L., Angulo, Y., Lomonte, B. and Gut- ierrez, J.M. (2009) Venoms, venomics, antivenomics. FE- BS Letters, 583, 1736-1743. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2009.03.029 [6] Kini, R.M. and Evans, H.J. (1992) Structural domains in venom proteins: Evidence that metalloproteinases and nonenzymatic platelet aggregation inhibitors (disintegrins) from snake venoms are derived by proteolysis from a common precursor. Toxicon, 30, 265-293. doi:10.1016/0041-0101(92)90869-7 [7] Marcinkiewicz, C., Weinreb, P.H., Calvete, J.J., Kisiel, D.G., Mousa, S.A., Tuszynski, G.P. and Lobb, R.R. (2003) Obtustatin: A potent selective inhibitor of alpha1beta1 integrin in vitro and angiogenesis in vivo. Cancer Re- search, 63, 2020-2023. [8] Ferreira, T.L. and Ward, R.J. (2009) The interaction of bothropstoxin-I (L ys49-PLA(2)) with liposome membranes. Toxicon, 54, 525-530. doi:10.1016/j.toxicon.2009.05.025 [9] Su, Z.Y. and Wang, Y.T. (2011) Coarse-grained molecular dynamics simulations of cobra cytotoxin A3 interactions with a lipid bilayer: Penetration of loops into membranes. Journal of Physical Chemistry B, 115, 796-802. doi:10.1021/jp107599v [10] Bagatolli, L.A. and Gratton, E. (2000) A correlation be- tween lipid domain shape and binary phospholipid mix- ture composition in free standing bilayers: A two-photon fluorescence microscopy study. Biophysical Journal, 79, 434-447. doi:10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76305-3 [11] Sanchez, S.A., Bagatolli, L.A., Gratton, E. and Hazlett, T.L. (2002) Two-photon view of an enzyme at work: Crotalus atrox venom PLA2 interaction with single-lipid and mixed-lipid giant unilamellar vesicles. Biophysical Journal, 82, 2232-2243. doi:10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75569-0 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  N. Ayvazyan et al. / Journal of Biophysical Chemistry 3 (2012) 44-48 48 [12] Mueller, P., Rudin, D.O., Tien, H. and Wescott, W.C. (1962) Reconstruction of cell membranes structure in vitro and its transformation into an excitable system. Nature, 194, 979-980. doi:10.1038/194979a0 [13] Hirota, S. and Duzgunes, N. (2011) Physico-chemical approach to targeting phenomena. Current Drug Discov- ery Technologies, 8, 286. doi:10.2174/157016311798109399 [14] Buchsteiner, A., Hauss, T., Dante, S. and Dencher, N.A. (2010) Alzheimer’s disease amyloid-beta peptide ana- logue alters the ps-dynamics of phospholipid membranes. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta, 1798, 1969-1976. doi:10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.06.024 [15] Qiu, L., Lewis, A., Como, J., Vaughn, M.W., Huang, J., Somerharju, P., Virtanen, J. and Cheng, K.H. (2009) Cho- lesterol modulates the interaction of beta-amyloid peptide with lipid bilayers. Biophysical Journal, 96, 4299-4307. doi:10.1016/j.bpj.2009.02.036 [16] Zakharyan, A.E. and Ay vazian, N.M. (2005) Modeling of BLMs in aspect of phylogenetic development of verte- brates. In: Ottova-Leitmannova, A., Ed., Advances in Pla- nar Lipid Bilayers and Liposomes, Elsevier, 238-259. [17] Ayvazyan, N.M. (2008) Application of the biophysical methodology in contemporary herpetology. Current Stud- ies in Herpetology, 8, 3-9. [18] Ayvazyan, N.M., Zaqarian, A.E. and Ghazaryan, N.A. (2011) Free radical oxidation and condition of membr- anes from brain lipids of vertebrates in the course of Vi- pera lebetina obtusa venom interaction. New Armenian Medical Journal, 3. [19] Kates, M. (1972) Techniques of lipidology: Isolation, analysis and identification of lipids. North-Holland Pub. Co., Amsterdam. [20] Mueller, P., Rudin, D., Tien, H. and Wescot, T.J. (1962) Reconstruction of cell membranes structure in vitro and its transformation into an excitable system. Nature, 194, 979-980. doi:10.1038/194979a0 [21] Leidy, C., Ocampo, J., Duelund, L., Mouritsen, O.G., Jørgensen, K. and Peters, G.H. (2011) Membrane restruc- turing by phospholipase A2 is regulated by the presence of lipid domains. Biophysical Journal, 101, 90-99. doi:10.1016/j.bpj.2011.02.062 [22] Jan, V., Maroun, R.C., Robbe-Vincent, A., De Haro, L. and Choumet, V. (2002) Toxicity evolution of Vipera aspis aspis venom: Identification and molecular modeling of a novel phospholipase A(2) heterodimer neurotoxin. FEBS Letters, 527, 263-268. doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(02)03205-2 [23] Fox, J.W. and Serrano, S.M.T. (2005) Snake toxins and hemostasis. Toxicon, 45, 951-1181. doi:10.1016/j.toxicon.2005.04.007 [24] Gasmi, A., Bourc ie r, C., Aloui, Z., Srairi, N., Marchett i, S. and Gimond, C. (2002) Complete structure of an increas- ing capillary permeability protein (ICPP) purified from Vipera lebetina venom. ICPP is angiogenic via vascular endothelial growth factor receptor signaling. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 277, 29992-29998. doi:10.1074/jbc.M202202200 [25] Chavushyan, V.A., Gevorkyan, A.Z., Avakyan, Z.É., Avetisyan, Z.A., Pogosyan, M.V. and Sarkisyan, D.S. (2006) The protective effect of Vipera raddei venom on peripheral nerve damage. Neuroscience and Behavioral Physiology, 36, 39-51. doi:10.1007/s11055-005-0161-7 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS

|