American Journal of Plant Sciences

Vol.06 No.08(2015), Article ID:56741,22 pages

10.4236/ajps.2015.68129

Vegetative Rhombic Pattern Formation Driven by Root Suction for an Interaction-Diffusion Plant-Ground Water Model System in an Arid Flat Environment

Inthira Chaiya1, David J. Wollkind2, Richard A. Cangelosi3, Bonni J. Kealy-Dichone3, Chontita Rattanakul1

1Department of Mathematics, Faculty of Science, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand

2Department of Mathematics, Washington State University, Pullman, USA

3Department of Mathematics, Gonzaga University, Spokane, USA

Email: dwollkind@wsu.edu

Copyright © 2015 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 26 March 2015; accepted 25 May 2015; published 28 May 2015

ABSTRACT

A rhombic planform nonlinear cross-diffusive instability analysis is applied to a particular interaction-diffusion plant-ground water model system in an arid flat environment. This model contains a plant root suction effect as a cross-diffusion term in the ground water equation. In addition a threshold-dependent paradigm that differs from the usually employed implicit zero-threshold methodology is introduced to interpret stable rhombic patterns. These patterns are driven by root suction since the plant equation does not yield the required positive feedback necessary for the generation of standard Turing-type self-diffusive instabilities. The results of that analysis can be represented by plots in a root suction coefficient versus rainfall rate dimensionless parameter space. From those plots regions corresponding to bare ground and vegetative patterns consisting of isolated patches, rhombic arrays of pseudo spots or gaps separated by an intermediate rectangular state, and homogeneous distributions from low to high density may be identified in this parameter space. Then, a morphological sequence of stable vegetative states is produced upon traversing an experimentally-determined root suction characteristic curve as a function of rainfall through these regions. Finally, that predicted sequence along a rainfall gradient is compared with observational evidence relevant to the occurrence of leopard bush, pearled bush, or labyrinthine tiger bush vegetative patterns, used to motivate an aridity classification scheme, and placed in the context of some recent biological nonlinear pattern formation studies.

Keywords:

Leopard Bush, Tiger Bush, Pearled Bush, Root Suction, Nonlinear Stability Analyses, Threshold-Dependent Pattern Formation

1. Introduction

von Hardenberg et al. [1] devised a plant-ground water (sometimes called soil water) interaction-diffusion system to model self-organized vegetative pattern formation in arid environments (reviewed by Rietkerk et al. [2] ). Here the positive feedback for an activator consumer (e.g., plants) in the plant equation and the self-diffusivity advantage for an inhibitory limiting resource (e.g., ground water) provided the necessary conditions for the onset of Turing [3] pattern formation. von Hardenberg et al.’s [1] model also included the effect of plant root suction by adding a cross-diffusion term in their ground water equation. Rietkerk et al. [4] performed numerical simulations using reflecting boundary conditions on a similar interaction-diffusion model system consisting of three partial differential equations describing the spatio-temporal behavior of plant density, soil water, and surface water, respectively, but excluding the root suction cross-diffusion term in their soil water equation. That model had been carefully developed by HilleRisLambers et al. [5] for a flat semi-arid grazing system.

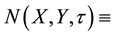

We wish to formulate an interaction-diffusion model system for  plant biomass density (gm/m2) and

plant biomass density (gm/m2) and  ground (soil) water content (mm of depth), where

ground (soil) water content (mm of depth), where  two-dimensional coordinate system (m, m) and

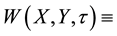

two-dimensional coordinate system (m, m) and  time (d), based upon the interaction terms of Rietkerk et al. [4] and the diffusion terms of von Hardenberg et al. [1] , defined on a flat unbounded arid environment. Toward that end, we first introduce the auxiliary dependent variable

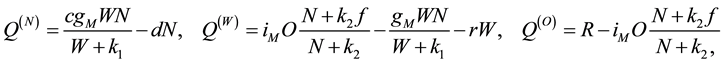

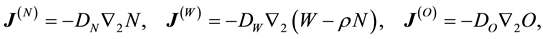

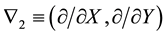

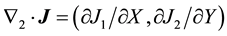

time (d), based upon the interaction terms of Rietkerk et al. [4] and the diffusion terms of von Hardenberg et al. [1] , defined on a flat unbounded arid environment. Toward that end, we first introduce the auxiliary dependent variable  surface water content (mm of depth) and the coupled interaction- diffusion model system given by

surface water content (mm of depth) and the coupled interaction- diffusion model system given by

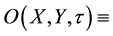

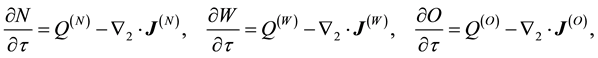

(1.1)

(1.1)

where ([1] [4] )

(1.2)

(1.2)

(1.3)

(1.3)

with  and

and  for

for . Here

. Here  maximum specific

maximum specific

water uptake rate by the plants,  conversion of water uptake by the plants to plant growth,

conversion of water uptake by the plants to plant growth,  specific loss rate of plant density due to mortality,

specific loss rate of plant density due to mortality,  half-saturation soil water constant relevant to specific plant growth and water uptake,

half-saturation soil water constant relevant to specific plant growth and water uptake,  specific loss rate of soil water due to evaporation and drainage,

specific loss rate of soil water due to evaporation and drainage,

More than forty years ago, Keller and Segel [6] proposed the initiation of slime mold aggregation viewed as an instability in a landmark paper with that title. They formulated a mathematical reaction-diffusion model system for the aggregation of the cellular slime mold Dictyostelium discoideum involving four dependent variables: Namely, the density of this amoeba; the concentrations of the acrasin and acrasinase produced by it which mediate its aggregation; and the concentration of an intermediate complex formed by these chemicals in a reversible reaction. Keller and Segel [6] then simplified that model to a two-component system involving just the density of the amoeba and the concentration of the acrasin by making Haldane’s assumption that the complex was in chemical equilibrium and the additional assumption that the total concentration of the acrasinase enzyme in both its free and bound state was a constant. This simplified model included flux terms deduced from Fickian self-diffusion of its two components and a chemotaxis term for the amoeba generated by the introduction of cross-diffusion involving the acrasin gradient.

For the sake of model analysis, HilleRisLambers et al. [5] introduced a quasi steady-state approximation in (1.1) by taking

Such an assumption is dependent upon

Then, introducing (1.4) into (1.1)-(1.2)-(1.3) by replacing the rate of infiltration term in

where

Our main purpose in doing so is to devise a model system of this sort that demonstrates root suction alone can generate the two-dimensional vegetative patterns (e.g., leopard bush, pearled bush, and labyrinthine tiger bush) occurring in arid flat environments as described by Rietkerk et al. [2] ).

2. Equilibrium Points and Their Linear Stability

There exist two equilibrium points of model system (1.5)

satisfying

given by

and

Note that (2.3) which exists for all parameter values corresponds to a bare ground or no vegetation situation while (2.4) which only exists for

corresponds to a community equilibrium point or a state exhibiting a nontrivial homogenous vegetative distribution. In this context, we adopt the far-field condition that

We next wish to examine the linear stability behavior of these critical points and shall proceed sequentially. That is we begin with (2.3) by considering a separation of variables solution to system (1.5) and boundary condition (2.6) of the form

and find that

Upon examination of (2.10) it follows that

Hence we can conclude that (2.11) represents the linear stability criterion for this bare ground equilibrium point. Since the community equilibrium point of (2.4) does not exist for these parameter values by virtue of (2.5), an exchange of stabilities between the two critical points of system (1.5) occurs at

The primary focus of our research is on the stability behavior of this community equilibrium point. Now introducing the nondimensional variables and parameters

we transform system (1.5) and far-field condition (2.6) into

where

and

Observe that the equilibrium point in question corresponds to

in our dimensionless formulation since

Here we are concerned with the stability of this solution to initially infinitesimal one-dimensional perturbations. Toward that end, we consider a reduced form of our basic system with

where

where

which are tabulated below for the relevant values of p and s.

Note that in (2.20) we have implicitly made use of the fact that

where

Table 1. Interaction expansion coefficients.

For fixed

Thus, when

The restriction of

3. One-Dimensional Analysis: Stuart [7] -Watson [8] Nonlinear Stability Results

In the previous section we deduced the critical conditions for the occurrence of cross-diffusive instabilities when

it is standard operating procedure to examine the weakly nonlinear stability of our community equilibrium point by letting [9]

where

Then, the substitution of this solution into (2.14)-(2.15)-(2.16) and the expansion of its interaction terms in a Maclaurin series, yields six vector problems: The O(1) problem is satisfied identically given that

the previous section with

two

Figure 1. Plot of

Figure 2. Plot of

where the components of

are catalogued in the Appendix.

The stability behavior of the Landau equation (3.3) is dependent upon the sign of

Figure 3. Plot of

From Figure 3 we observe that

Given these conditions, we may conclude that there exist two supercritical cases when

of amplitude

in dimensionless and dimensional variables, respectively. These supercritical stripes are plotted in Figure 4(a) where regions of higher density

When

Finally we synthesize the one-dimensional pattern formation results of this and the previous section in the

4. Two-Dimensional Analysis: Rhombic-Planform Nonlinear Stability Results

Wishing to refine our one-dimensional predictions summarized in Figure 4(b) and to investigate the possibility

Figure 4. (a) Contour plot of the supercritical stripes of (3.7)-(3.8). Here, the x-variable is measured in units of

of occurrence of the two-dimensional vegetative patterns mentioned earlier, we next consider a rhombic-plan- form solution of system (2.14) of the form [10]

where

with an analogous expansion for

Here we are employing the notation

we again obtain a sequence of problems, each of which corresponds to one of these terms. Solving those problems we find that

while applying the same method of analysis, as employed for deducing (3.4), to the

where the components of

as well as the solutions for the relevant second-order systems are catalogued in the Appendix.

The rhombic-planform amplitude Equations (4.3)-(4.4) possess the following equivalence classes of critical points

Assuming that

Note that I and II, as in the one-dimensional analysis of the previous section, represent the uniform homogeneous and supercritical striped states, respectively, while V can be identified with a rhombic pattern possessing characteristic angle

and plotting that quantity versus

provided in addition that

Figure 5. Plot of

Now, repeating the process used to produce Figure 5 but for other values of

Restricting ourselves to the interval of interest

Here, these properties of (4.12) are a consequence of mode interference occurring exactly at

Finally, we present a morphological interpretation of the stable rhombic patterns that can be associated with critical point V for the values of the characteristic angle relevant to Table 3. Then, to lowest order, the equilibrium vegetative pattern corresponding to that critical point satisfies

Figure 6. Plot of

Table 2. Range of

Table 3. Angle range for stable rhombic patterns.

The three parts of Figure 7 are threshold contour plots of (4.14) for

For fixed values of the other parameters and

is a dimensionless measure of the rainfall rate R. We now wish to select a particular

represents this threshold instead. Then, when

Figure 7. Rhombic patterns relevant to

Given their appearance in Figure 7 we label these upper, zero, and lower threshold type rhombic vegetative arrays as pseudo spots, rectangles, and pseudo gaps and denote them by

5. Morphological Interpretations and Comparisons.

As a prelude to the morphological interpretations to be developed in this section, we first demonstrate that our model system does not generate any hexagonal patterns. We do so by considering a hexagonal-planform expansion for

where, for

with a similar expansion for

which reduces (5.1) and (5.2)-(5.3) to

with a similar expansion for

See equation (4.4) of Wollkind and Stephenson [10] for the explicit higher-order terms in these expansions of

(5.6)-(5.7) proportional to

Then upon substitution of (5.6)-(5.7) into (2.14) we find that (4.5) holds again while

for

as defined in Section 3. If we proceed in the same manner as we did with the rhombic-planform expansions of the last section, the Fredholm-type solvability conditions for

where the components of

for

hence is often referred to as a free mode which is why that component is not catalogued in the Appendix.

The six-disturbance hexagonal-planform amplitude phase-Equations (5.2)-(5.3) have equivalence classes of critical points given by

I:

II:

IV:

Critical points I and II represent the uniform homogeneous and supercritical striped states described in the previous two sections;

lized cell that reduces to II for

and orbital stability of these critical points depends, in part, upon the signs of various combinations of the Landau constants of (5.2)-(5.3), we examine the signs of

Although I is stable for

Having established this fact, let us return to the subject with which we ended the last section: Namely, the selection of the proper value to be assigned for

Figure 8. Plots of

first summarize the simulation results of Rietkerk et al. [4] . Their two-dimensional numerical simulations of model system (1.1), with

Thus, from our rhombic planform analysis of the previous section, we can make the prediction that

Figure 9 represents the two-dimensional refinement of our one-dimensional predictions of Figure 4(b). Observe that the occurrence of striped and rhombic patterns is mutually exclusive by virtue of stability criteria (4.9). Hence since rhombic patterns occur for all

So far, with the implicit exception of the above-mentioned

Figure 9. Stability diagram in the

tion equation describing vegetative pattern formation in arid isotropic environments led to the conjecture that when

Taking into account the next higher-order term in the expansions and the amplitude equation of (3.1)-(3.2)- (3.3) when

and calculating

the potentially stable equilibrium points 0 and

Determining the generalized marginal curve for our problem analogous to (2.24) but with

where

in Figure 9, we could make the proper morphological identifications. These would differ from those already appearing in this figure only due to the presence of the overlap region

Traditionally, morphological sequences of the sort referred to above have been generated from stability diagrams such as Figure 9 by traversing appropriate horizontal or vertical lines in that two-component parameter space (e.g., Cangelosi et al. [14] ; Kealy and Wollkind [24] ). A procedure of this sort is inherently dependent upon the implicit assumption that these two components are independent of each other. In the case of Figure 9, however,

Note in (5.15) the units for

where

Here

where, specifically,

Upon recalling that

and substituting (5.20) into (5.18)-(5.19), yields

where, specifically,

Hence

Finally, selecting

where

We plot this curve with

where, specifically,

Here, from (5.20), these

respectively. In this context, we define

where

Thus, isolated patches are only predicted for transit curves of the form of (5.24)-(5.25) provided

We next compare these theoretical predictions with relevant observational evidence. The relevant reported vegetative patterns [2] consist of spots (leopard bush) and gaps (pearled or spotted bush). After Boonkorkuea et al. [1] , we now associate our rhombic arrays of pseudo spots (

Designating the

Then, we can see from (5.31) and (5.32) that

and hence conclude that the vegetative distributions of spots in leopard bush have a tendency to be more widely spaced than the bare patches which regularly punctuate the vegetation cover in pearled bush [26] . Employing the length scale of (3.8) and the parameter values of (2.25)-(2.26), yields the associated dimensional wavelength relationships

consistent with field observations and in agreement with Boonkorkuea et al. [13] , who interestingly enough found an identical power law relationship to (5.31) between their pattern wavelength and plant biomass for the evolution equation of Lejeune et al. [19] .

It remains for us to compare our results with those from some recent biological nonlinear pattern formation studies. We begin with the work of Gowda et al. [27] . These authors examined the standard sequence of patterned states (gaps ® labyrinth ® spots) generated in a general activator-inhibitor reaction-diffusion system as a bifurcation parameter was varied and then applied their results to the particular von Hardenberg et al. [1] plant-ground water model as its precipitation parameter was decreased. They employed both numerical simulation and analytical weakly nonlinear hexagonal-planform bifurcation methods. Gowda et al. [27] found, for the default set of parameter values von Hardenberg et al. [1] used in their numerical integration, that, although the simulation method reproduced the latter’s standard sequence, the hexagonal planform analysis as in our problem failed to predict vegetative patterns. These calculations, in accordance with (2.25)-(2.26), were performed for

We end this phase of our discussion by restating von Hardenberg et al.’s [1] claim that the power of model systems such as ours of (1.5) is their predicted sequence of stable states along a rainfall gradient such as the one summarized in Table 4 can be used to motivate an aridity classification scheme which is characterized by the three rainfall thresholds

Here we are employing the notation of von Hardenberg et al. [1] for these dimensionless rainfall (precipitation) rate thresholds and use them to introduce the following possible aridity classes based upon the inherent vegetative states of our system:

・ Dry-subhumid (

・ Semiarid (

・ Arid (

・ Hyperarid (

Table 4. Morphological stability predictions along a rainfall gradient for

As pointed out by von Hardenberg et al. [1] the advantage of the proposed aridity classification scheme pertains to the information it contains about dynamical aspects of drylands. Regions whose aridity classes imply the occurrence of upper threshold vegetative patterns, isolated patches, or a sparse homogeneous distribution are vulnerable to desertification. The mere knowledge of that threat, however, allows land managers to reverse this process for those regions by implementing crust disturbance, seed augmentation, or irrigation strategies. Meron et al. [29] suggested a cycling mechanism between plants and water to account for the formation of bare patches characteristic of vegetative patterning along such a precipitation gradient. Note that a process of this sort occurs in all directions for two-dimensional vegetative patterns (pseudo spots or gaps, rectangles, and isolated patches) but only in two directions for one-dimensional ones (stripes).

We close with a more detailed commentary on the role played by cross-diffusion in generating pattern formation instabilities for our two-component model system. Given that

Thus that assignment would yield the root suction characteristic curve

which, as a decreasing function of

6. Conclusions

In summary, we formulated an interaction-diffusion plant-ground water model system in an arid flat environment. That system basically was formed from two existing models by coupling a simplified version of the interaction terms of one of those systems with the exact diffusion terms of the other. These terms included a cross- diffusion effect in the ground water equation due to plant root suction and a nonautocatalytic effect in the plant equation that precluded the occurrence of Turing self-diffusive instabilities. We then performed a rhombic planform nonlinear cross-diffusion instability analysis on that system and found an interval of characteristic angles for which stable rhombic patterns occurred. Defining a critical plant biomass threshold to interpret such rhombic arrays, those patterns were of an upper, zero, and lower threshold type which we labeled as pseudo spots, rectangles, and pseudo gaps, respectively. Our main result could be plotted in a coefficient of root suction versus a rate of rainfall parameter space. Traversing that parameter space along an experimentally determined root suction characteristic curve as a function of rainfall, we produced a predicted morphological sequence of vegetative patterns consisting of bare ground, isolated patches, these rhombic arrays, and uniform homogeneous distributions from low to high density. Then that predicted sequence of stable states along a rainfall gradient was shown to be in good qualitative and quantitative agreement with observations involving the occurrence of leopard bush, labyrinthine tiger bush, and pearled bush in arid flat environments including the wavelength behavior of such patterns. Finally, we introduced an aridity classification scheme, with classes based upon the inherent vegetative patterns included in that predicted morphological sequence along a rainfall gradient, which could be used to anticipate desertification and subsequently to implement land management reversibility strategies. Implicit to our continuum formulation were the assumptions that the pattern wavelength was relatively large when compared with the mean coverage diameter of an individual plant but quite small when compared with the territorial length scale characteristic of the arid environment which allowed us to have considered our interaction-diffusion equations on an unbounded spatial domain [32] .

We conclude by noting that although these results of our weakly nonlinear stability analyses are asymptotically valid only in the neighborhood of the marginal stability curve and the rhombic vegetative arrays along our specific coefficient of root suction characteristic curve occurred in this region, numerical simulations of pattern formation for several reaction-diffusion systems and evolution model equations have shown that such theoretical predictions can be extended to regions of the relevant parameter space relatively far from the marginal curve [13] [33] . Given that a weakly nonlinear hexagonal planform analysis of our system did not predict any stable patterns, we also offered an alternative explanation involving these stable rhombic patterns for why numerical simulations analyses of similar systems have in the past yielded periodic pattern formation over a parameter range where theoretical weakly nonlinear hexagonal ones did not. We finish by reiterating for the purpose of emphasis the fact that all of our pattern formation results for this model have been generated by the cross-diffusion process of root suction as opposed to the mediating effect it has often had on self-diffusion generated Turing patterns.

References

- von Hardenberg, J., Meron, E., Shachak, M. and Zarmi, Y. (2001) Diversity of Vegetation Patterns and Desertification. Physical Review Letters, 87, Article ID: 198101. http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.87.198101

- Rietkerk, M., Dekker, S.C., de Ruiter, P.C. and van de Koppel, J. (2004) Self-Organized Patchiness and Catastrophic Shift In Ecosystems. Science, 305, 1926-1929. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1101867

- Turing, A.M. (1952) The Chemical Basis of Morphogenesis. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 237, 37-72. http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rstb.1952.0012

- Rietkerk, M., Boerlijst, M.C., van Langevelde, F., HilleRisLambers, R., van de Koppel. J., Kumar, L., Prins, H.H.T. and de Roos, A.M. (2002) Self-Organization of Vegetation in Arid Ecosystems. The American Naturalist, 160, 524- 530. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/342078

- HilleRisLambers, R., Rietkerk, M., van den Bosch, F., Prins, H.T.H. and de Kroon, H. (2001) Vegetation Pattern Formation in Semi-Arid Grazing Systems. Ecology, 82, 50-61. http://dx.doi.org/10.1890/0012-9658(2001)082[0050:VPFISA]2.0.CO;2

- Keller, E.F. and Segel, L.A. (1970) Initiation of Slime Mold Aggregation Viewed as an Instability. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 26, 399-415. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0022-5193(70)90092-5

- Stuart, J.T. (1960) On the Nonlinear Mechanics of Wave Disturbances in Stable and Unstable Parallel Flows, Part 1. The Basic Behavior of Plane Poiseuille Flow. Journal of Fluid Mechanics, 9, 353-370. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S002211206000116X

- Watson, J. (1960) On the Nonlinear Mechanics of Wave Disturbances in Stable and Unstable Parallel Flows, Part 2. The Development of a Solution for Plane Poiseuille Flow and Plane Couette Flow. Journal of Fluid Mechanics, 9, 371- 389. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0022112060001171

- Wollkind, D.J., Manoranjan, V.S. and Zhang, L. (1994) Weakly Nonlinear Stability Analyses of Reaction-Diffusion Model Equations. SIAM Review, 36, 176-214. http://dx.doi.org/10.1137/1036052

- Wollkind, D.J. and Stephenson, L.E. (2000) Chemical Turing Pattern Formation Analyses: Comparison of Theory with Experiment. SIAM Journal of Applied Mathematics, 61, 387-431. http://dx.doi.org/10.1137/S0036139997326211

- Geddes, J.B., Indik, R.A., Moloney, J.V. and Firth, W.J. (1994) Hexagons and Squares in a Passive Nonlinear Optical System. Physical Review A, 50, 3471-3485. http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.50.3471

- Cross, M.C. and Hohenberg, P.C. (1993) Pattern Formation outside of Equilibrium. Reviews of Modern Physics, 65, 851-1112. http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.65.851

- Boonkorkuea, N., Lenbury, Y., Alvarado, F.J. and Wollkind, D.J. (2010) Nonlinear Stability Analyses of Vegetative Pattern Formation in an Arid Environment. Journal of Biological Dynamics, 4, 346-380. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17513750903301954

- Cangelosi, R.A., Wollkind, D.J., Kealy-Dichone, B.J. and Chaiya, I. (2014) Nonlinear Turing Patterns for a Mussel-Algae Model. Journal of Mathematical Biology, 70, 1249-1294. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00285-014-0794-7

- Segel, L.A. (1965) The Nonlinear Interaction of a Finite Number of Disturbances to a Fluid Layer Heated from Below. Journal of Fluid Mechanics, 21, 359-384. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S002211206500023X

- Segel, L.A. and Stuart, J.T. (1962) On the Question of the Preferred Mode in Cellular Thermal Convection. Journal of Fluid Mechanics, 13, 289-306. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0022112062000683

- Kuske, R. and Matkowsky, B.J. (1994) On Roll, Square, and Hexagonal Cellular Flames. European Journal of Applied Mathematics, 5, 65-93. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0956792500001303

- Wollkind, D.J. (2001) Rhombic and Hexagonal Weakly Nonlinear Stability Analyses: Theory and Applications. In: Debnath, L., Ed., Nonlinear Stability Analysis, Volume II, WIT Press, Southampton, 221-272.

- Lejeune, O., Tildi, M. and Couteron, P. (2002) Localized Vegetation Patches: A Self-Organized Response to Resource Scarcity. Physical Review E, 66, Article ID: 010901. http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.66.010901

- Chen, W. and Ward, M.J. (2011) The Stability and Dynamics of Localized Spot Patterns in the Two-Dimensional Gray-Scott Model. SIAM Journal of Dynamical Systems, 10, 586-666. http://dx.doi.org/10.1137/09077357x

- Wang, R.-H., Liu, Q.-X., Sun, G.-Q., Zhen, J. and van de Koppel, J. (2009) Nonlinear Dynamic and Pattern Bifurcation in a Model for Spatial Patterns in Young Mussel Beds. Journal of the Royal Society Interface, 6, 705-718. http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2008.0439

- Liu, Q.-X., Doelman, A., Rottschäfer, V., de Jager, M., Herman, P.M.J., Rietkerk, M. and van de Koppel, J. (2013) Phase Separation Explains a New Class of Self-Organized Spatial Patterns in Ecological Systems. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 110, 11905- 11910. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1222339110

- Oulton, D.B. and Wollkind, D.J. (1982) A Three-Dimensional Nonlinear Stability Analysis of the Solidification of a Dilute Binary Alloy. Old Dominion University Research Foundation, Norfolk.

- Kealy, B.J. and Wollkind, D.J. (2012) A Nonlinear Stability Analysis of Vegetative Turing Pattern Formation for an Interaction-Diffusion Plant-Surface Water Model System in an Arid Flat Environment. Bulletin of Mathematical Biology, 74, 803-833. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11538-011-9688-7

- Roose, T. and Fowler, A.C. (2004) A Model for Water Uptake by Plant Roots. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 228, 155-171. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jtbi.2003.12.012

- Lejeune, O., Tildi, M. and Lefever, R. (2004) Vegetation Spots and Stripes in Arid Landscapes. International Journal of Quantum Chemistry, 98, 261-271. Couteron, P., Mahamane, A., Ouedraogo, P. and Seghieri, J. (2000) Differences between Banded Thickets (Tiger Bush) in Two Sites in West Africa. Journal of Vegetation Sciences, 11, 321-328.

- Gowda, K., Riecke, H. and Silber, M. (2014) Transitions between Patterned States in Vegetation Models for Semiarid Ecosystems. Physical Review E, 89, Article ID: 022701(1-8). http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.89.022701

- Couteron, P., Mahamane,A., Ouedraogo, P. and Seghieri, J. (2000) Differences between Banded Thickets (Tiger Bush) in Two Sites in West Africa. Journal of Vegetation Sciences, 11, 321-328.

- Meron, E., Gilad, E., von Hardenberg, J., Shachuk, M. and Zarmi, Y. (2004) Vegetation Patterns along a Rainfall Gradient. Chaos, Solitons, and Fractals, 19, 367-376. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0960-0779(03)00049-3

- Stancevic, O., Angstmann, C.N., Murray, J.M. and Henry, B.I. (2013) Turing Patterns from Dynamics of Early HIV Infection. Bulletin of Mathematical Biology, 75, 774-795. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11538-013-9834-5

- Wang, W.-M., Wang, W.-J., Lin, Y.-Z. and Tan, Y.-J. (2011) Pattern Selection in a Predation Model with Self and Cross Diffusion. Chinese Physics B, 20, Article ID: 034702(1-8). http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/1674-1056/20/3/034702

- Graham, M.D., Kevrekidis, J.G., Asakura, K., Lauterbach, J., Krishner, K., Rotermund, H.-H. and Ertl, G. (1994) Effects of Boundaries on Pattern Formation: Catalytic Oxidation of CO on Platinum. Science, 264, 80-82. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.264.5155.80

- Golovin, A.A., Matkowsky, B.J. and Volpert, V.A. (2008) Turing Pattern Formation in the Brusselator Model with Superdiffusion. SIAM Journal of Applied Mathematics, 69, 251-272. http://dx.doi.org/10.1137/070703454

Appendix

In this appendix we catalogue the nonhomogeneous terms and second-order solutions relevant to our expansions of (3.1)-(3.2)-(3.3), (4.1)-(4.2)-(4.3)-(4.4), and (5.4)-(5.5)-(5.6)-(5.7).

For (3.1)-(3.2)-(3.3) we have:

where

with

and

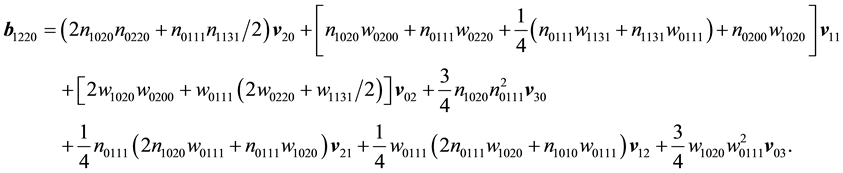

For (4.1)-(4.2)-(4.3)-(4.4) we have:

where

for

For (5.4)-(5.5)-(5.6)-(5.7) we have:

where

and

(5.54)

(5.54)