Open Journal of Nursing

Vol.3 No.1(2013), Article ID:29564,8 pages DOI:10.4236/ojn.2013.31017

A qualitative study of the Omani physicians’ lived experience with truth disclosure to cancer patient

![]()

1Behavioral Medicine, Sultan Qaboose University Hospital, Muscat, Oman

2College of Nursing, King Saud University, Riyadh, KSA

Email: ahmedsaid-777@hotmail.com, nzakari@hotmail.com

Received 30 January 2013; revised 7 March 2013; accepted 16 March 2013

Keywords: Telling the Truth; Ethics; Cancer; Communication; Oman; Health Care Provider

ABSTRACT

Objectives: The purpose of this phenomenological Qualitative Study is to gain an in depth understanding of the nature and meaning of the experiences of physicians in relation to truth disclosure and ethics of veracity when diagnosing cancer. Methods: A qualitative phenomenological study using semi-structured interviews was conducted at Sultan Qaboos university hospital (SQUH), l to explore the Omani Physicians’ lived experiences with truth disclosure in patients who were diagnosed with cancer. The target population for this study is Omani physicians working in SQUH. The total of four participants was involved in this study. Results: Three essential themes were generated through the analysis of the participants’ descriptions of their perceptions and lived experiences as the following with their subthemes: the first theme is the clinical aspect of the experiences with three subthemes: 1) The ethical aspect and the physician’s attitude; 2) The strategy of breaking bad news; 3) Training and breaking bad news. The second theme is Cultural diversity with three subthemes: 1) Relatives preference; 2) The patient education; 3) The hospital setting. The third theme is the emotional aspect of the experiences with five subthemes: 1) Emotional sadness; 2) Personal grief; 3) Other emotions; 4) The positive emotions; 5) Control of the emotions. Conclusion: This study recommends: to build up appropriate measures and guidelines on the subject of truth telling and medical ethics, and to provide more training for the health care providers in the context of breaking bad news. In addition to add to the curriculum of medical colleges the basic ethical principles relevant to medical practice. Finally, to establish medical social work departments in SQUH, and other healthcare institutions in Oman.

1. INTRODUCTION

Very little information is available in relation to truth telling practice in health care setting in Oman. Most of the Omani hospitals have not established a clear policy to guide the practice of the physician in the context of truth telling. The debate on the issue of truth telling is at the core of the contemporary biomedical ethics. There is delicate interplay between autonomy and beneficence which made some differences in truth telling between the cultures, from the in medicine [1]. In the case of a cancer patient, physicians sometimes must decide whether the patient should be informed about the truth of his diagnosis and prognosis or not [2]. Disclosing the diagnosis of cancer has a great psychological impact on the patient as it is a life-threatening condition [3-5]. For many patients, cancer might be considered as a reminder of death. It is remarkably difficult to talk about death and its meaning [2]. On the other hand, some believe that the patient should be encouraged to make appropriate arrangements for personal matters. For instance, a patient needs time to set his life in order to make a will, take a trip, and so on. Some patients not only want to be free from pain and suffering as they die, they also wish to have the opportunity to make peace with God, to resolve personal conflicts, and to make financial plans before death [2]. Telling the patient about the truth ensures that the correct information is given and the correct decision for the patient is made [6-9]. The standard of professional candor with patients has undergone a significant change over the past 30 years. Apart from their obligation to disclose information necessary to obtain consent, physicians are increasingly expected to communicate important information to patients that is not immediately related to treatment decisions [10,11]. Cultures that place a higher value on beneficence and nonmaleficence relative to autonomy have a long tradition of family-centered health care decisions. In this collective decision process, relatives receive information about the patient’s diagnosis and prognosis and make treatment choices, often without the patient’s input [12]. Family members acting as surrogates for their loved ones often request that the truth be withheld, usually to prevent what is perceived as possible terrible harm to their loved one [13,14].

Truth telling fosters trust in the medical profession and rests on the respect owed to patients as persons. It also prevents harm as patients who are not informed about their situation may fail to get medical help when they should [15]. It is interesting that arguments for and against truth-telling are based on autonomy and physical and psychological harm. The aim of this study is to explore physicians’ perceptions of lived experience of truth disclosure to cancer patient in order to understand the essence and nature of this phenomenon.

2. METHODS

The methodology in this research study is consistent with Max Van Manen’s hermeneutic, phenomenological method of research. van Manen’s phenomenological approach involves the following steps: 1) investigating an issue that merits attention based on its relevance to the members of a particular community, 2) investigating the experience by asking participants to describe and express thoughts and feelings that occurred during a specific time period, 3) extracting and reflecting on essential themes that characterize the phenomenon, 4) describing the phenomenon through writing and rewriting in order to refine and clarify the common themes, and 5) utilizing the researcher’s personal experiences in order to interpret these themes [16,17]. In the hermeneutic, phenomenological method, the researcher interprets the stories of each participant to illuminate their meaning and essence. The researcher asks the participant to return to their lived experience and to describe his or her experience of the phenomena. The researcher then explores this lived experience, which preceded scientific schematization [18].

The research was conducted at Sultan Qaboos university hospital (SQUH) in the Sultanate of Oman. SQUH is a tertiary care hospital that is considered one of the top hospitals in the country in relation to patient care and qualification of its staff. A specific setting for each interview was determined based on each participant’s interest and convenience in order to allow participants to speak freely without external interruption. Sites for meetings included conference rooms and offices. The target population for this study is Omani physicians working in SQUH, Participants’ inclusion criterion were as the following: 1) an Omani physician, 2) a current employee of SQUH, 3) a physician who has at least one year of medical experience at SQUH, 4) a physician who had experience with cancer patients. Participants were recruited by using direct personal contact with participants in accordance with the inclusion criteria, through snowball samplings in which participants were asked if they were aware of others who may be interested in participating in the study, and finally through information gathered from friends and colleagues in the hospital. Each participant was contacted to assess his/her willingness to participate in the study and to determine an interview time and place that would be convenient for him/her. Each participant was interviewed separately. The total of four participants was involved in this study.

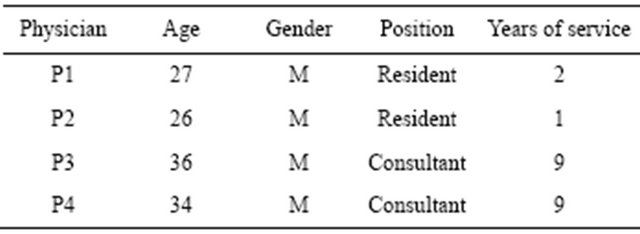

Demographic Data: the participants in this study consist of Omani physicians working at SQUH. The total number of participants was four physicians (see Table 1). The physicians were all males. This group consisted of two consultants, and two residents whose ages ranged from 26 to 36 years. Their years of experiences varied from one year to 9 years.

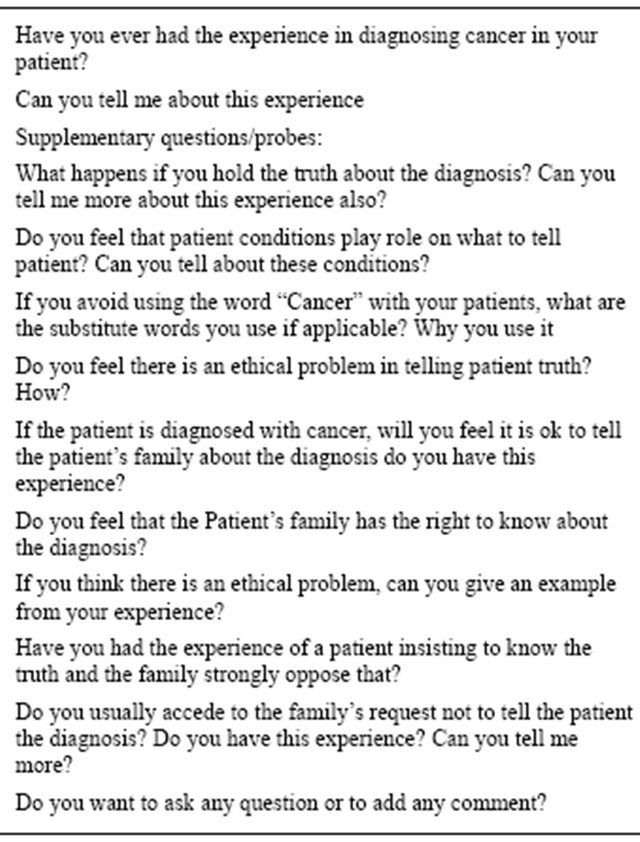

Approval was obtained from the human subject review board at Sultan Qaboos University before conducting the study. The participants were assured that participation in the study is voluntarily and they may withdraw from the study at any time and for any reason. Interviews were scheduled at time and place convenient for each participant. Each participant received a copy of the informed consent form to read and sign prior to participation in the study. Participants were informed that interviews will be tape-recorded, all information collected in the study will be confidential, participants’ identities will be coded, and pseudonyms will be used to protect participants’ identity. Participants were also assured that interview tapes will be kept in the possession of the researcher and will be destroyed after the study is completed. Also, participants were informed that the study is part of a dissertation project. Demographic data was obtained in relation to participant’s age, gender, education, marital status, and years of experience for healthcare providers. All data resources including informed consent, demographic sheets, interview tapes and transcripts were coded. All interviews were tape-recorded. The interviews were run based on an open-ended semi-structured format. Although an interview guide of open-ended questions was used during the interviews (see Table 2).

The proposed questions were not necessarily followed in sequence. The focus of the dialogue questions were on participants’ descriptions of their lived experiences. Each

Table 1. Participants’ demographic data and the years of service in SQUH.

Table 2. The in-depth question.

participant was allowed to describe his stories and experiences with minimum interference or interruption from the researcher. An interview was further elaborated by asking participants to give specific examples and provide detailed descriptions of his/her experience. Additional questions followed in order to provide more clarification and insight to the discussion. During each interview, notes were taken regarding the interview process and non-verbal communication. Following the interview, notes were taken about the researcher’s impression on the information generated from the interview and whether the interview provided an in-depth exploration of the phenomenon. This evaluation process was useful for the subsequent interviews in order to formulate further questions to clarify the topic. In addition, these notes reflected the researcher’s feelings about the phenomenon and whether the interview provided similar or different perceptions and viewpoints. These reflective notes were also useful during the phenomenological reflection and phenomenological writing. Data saturation was determined when new participants’ stories and perceptions become similar to the previous findings, and do not lead to generating new themes, for that the sample size of four participants was enough. Then the next step was the interpretation of the meanings embedded in the data and the development of a framework to describe the decision making process and the feeling about telling the truth and the identification of the factors which influenced the decision made. Thematic data analysis as described by Van Manen (1990) was followed in the analysis of this study according to the following steps: 1) Listening and relistening to the audiotapes of the interviews to grasp the parts and the whole of the text; 2) Transcribing the interviews verbatim word by word; 3) Reading and re-reading every transcript to highlight with different colors the emerging themes that seemed to be related to the phenomenon under study, thus seeking the fundamental meaning of the experience; 4) The researcher identified the typical quotations from each dialogue that were distinctive with different themes; 5) To turn back to the transcript to verify the understanding. During this stage, the essential themes were identified. These essential themes are then called upon to help guide the selected antidotes from the participants’ stories in an effort to further exemplify the essence(s) of the health care provider lived experience when encountered with diagnosis of cancer.

3. RESULTS

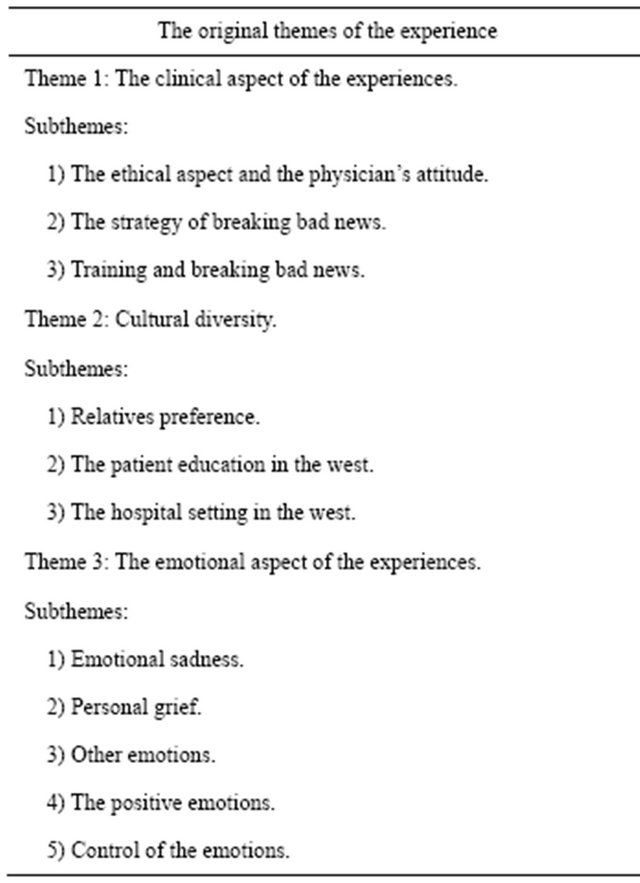

Three main themes were obtained with a number of emerging subthemes: the first theme is the clinical aspect of the experiences with three subthemes: 1) the ethical aspect and the physician’s attitude; 2) the strategy of breaking bad news; 3) training and breaking bad news. The second theme is Cultural diversity with three subthemes: 1) relatives’ preference; 2) the patient’s education; 3) the hospital setting. The third theme is the emotional aspect of the experiences with five subthemes: 1) emotional sadness; 2) personal grief; 3) other emotions; 4) the positive emotions; 5) control of the emotions (Table 3).

The first theme: the clinical aspect of the experiences.

The first theme contains three subthemes: 1) the ethical aspect and the physician’s attitude; 2) the strategy of breaking bad news; 3) training and breaking bad news.

1) The ethical aspect and the physician’s attitude The first subtheme is related to the ethical side and the physician’s attitude towards the truth disclosure, which showed a need for more training and education in the context of medical ethics both for the health care providers and for the public.

One of the participants said when I asked him: do you think there is an ethical problem here? He should know that he had a malignancy and he should know that he is on chemotherapy. I don’t think we should do anything other than that. Another participant said: every patient has his own right and the right to know their diagnosis because we are Muslims and a lot of things follow this. Plans in the patient mind he wants to do them before dying. May be there is a will to write it before he dies. But it happened very frequently actually that some patients died before knowing their diagnosis.

Table 3. The original themes of the experience and the extracted subthemes.

2) The strategy of breaking bad news The physicians there were following a strategy as follows:

The approach for breaking bad news is gradual and stepwise pattern. The senior physicians usually break the bad news. The place where the physician discloses the truth about the diagnosis is usually a side room. The first step in bad news breaking is talking about sign and symptoms of the patient and his investigation (to prepare the patient mentally). Starting by showing the patient how blood is formed. Let the patient ask if he had any questions. The second step is telling the patient what is abnormal in his blood test till reaching to the discussion that it is a tumour. The first word used is tumour (“waram” in Arabic), then cancer (saratan, in Arabic) or Marad Khabeeth, but not in the same session. Once telling the patient that he has cancer, put positive things. The third step is to go for the whole details. If the patient is unable to communicate, the relatives become the major persons to know the truth. The children must know the truth.

3) Training and breaking bad news In the oncology and hematology department, no formal training is given in communicating the bad news.

One of the participants said: this is something important for our job. I remember in one of the leukemia clinics I attended that my consultant wanted me to break bad news and he was observing what is happening. It was not like a formal training. There is nothing like a lecture or meetings. They just talk about this, although we had some lectures, regarding that … I think it is a matter that is more important than having a lecture about how to handle it is to practice it with somebody who’s familiar with this and you practice it in front of them so they know your approach.

The second theme: cultural diversity The following three subthemes were extracted: 1) Relatives preference; 2) The patient education in the west; 3) The hospital setting in the west.

1) Relatives preference One of the participants said: most the of it is a cultural problem, a cultural behaveior … what I see occasionally a patient ... a patient relative who is not willing to hear a lot of details or they don’t want the patient to know anything that is a big challenge for us. When I asked one of the participants whether this problem exists in the Omani culture; whether the family always wants to withhold the truth? He answered not always I just said most of the time. The relatives are very resistant to open the topic with the patient. You handle situation that the family ask you not to tell the patient more than once … I get 2 sons 3 sons of the patient sitting in front of me and telling me please don’t tell our father anything. The sons of the patient told me please tell him you had nothing … that basically lying to the patient … I told them sorry, I cannot do, I have to tell him, at least part of it. Regarding the second subtheme the patient education, one of the participants said: I mean in North America generally the majority of the patients in terms of wanting to know they are keen, they want to know in details they want to know the treatment they are offering them, they want to know the side effects of this therapy. 3. The hospital setting in the west is more advanced there is a need to improve our services: one of the participants said: the other difference there is that the setting is more supportive in the hospital, there is social workers, the nurses are more trained and equipped, the other health care workers, and for students and residence they trained too … You get a lot of variations. The third them: the emotional aspect of the experiences. The emotional side is very important in this experience, both for the physician and the patient. Five subthemes were extracted. 1. Emotional sadness. The question they were asked was: can you tell me more about your emotion when you discover the diagnosis of cancer in you patient?

For example, one of the participants said: it is a sad thing to diagnose someone with cancer. It is sad for us to diagnose somebody with cancer. It is always bad news. It is always sad to deal with the sick patient … emotional feelings as a physician should not be over expressed in front of the patients. I think.

2) Personal grief One of the participants stated: the other side of my experience by the time you feel close to the patients as you meet him in the outpatient department and in the day care. So the rapport with the patient increased. You keep looking for the patient until the end of his life. This creates a lot of problems. You can really feel that these patients become very close to you. Whenever the patient is deteriorating many times we cried a lot.

3) The other emotions One of the participants said: I just hate to see the patient get collapse. Usually they died in a very painful way & this is very emotional. The other participant stated that: so sometimes this causes some anxiety for us and some phobia from something not expected that can happen to him any time. Another participant said: dealing with cancer patient is properly the more stressful thing because unfortunately a lot of patients will die.

4) The positive emotions One of the participants said: it tells you what wealth of your life in your health. We thank Allah. It tells you the volume of the life; we should be prepared for all the things in our life. Another participant stated: but at the same time you feel gratification you are dealing with a sick patient who within a month 2 month or 3 month in most of the cases fortunately they are doing well … but you know the good thing about dealing with cancer patients and my good thing of dealing with all the pt you see a pt who comes in extremely in a very sick and you see they are leaving the hospital in a good status in a reasonable condition and you see them in your clinic, you are following them from a visit to another.

5) Control of the emotions One of the participants stated: you don’t want to be tearful, so depressed in front of the patient otherwise the patient will be even worse. What you started with you have to be sympathetic with this problem may be sad in the news but being a physician or medical professional of course you have to make sure that you not over mixing your own emotions to large extent with your decision making. The second part in this theme of the emotional side of the experience is the reaction of the patients when they received the news of the diagnosis, which was a normal human reaction to bad news.

One of the participants described it as the following: Nothing out of abnormal, nothing out of ordinarily. I mean it is always suspected that the patient will go into sever shock after you till them this bad news of obviously if you do it in a stepwise pattern you don’t want from the beginning to face the patient ok you have leukemia. It is not the right way of doing it. I mean you have to go through this slowly give the patient time to digest the information sometimes you can even give them day or two before reach to that final word. The word cancer that the goal obviously ultimately you have to tell them. In terms of unusual nothing really unusual the patient crying and the patients are differ in their responses, some of them responded in an aggressive somewhat aggressive way of being accusation or by accusing his physician neglect. So all expected normal human behavior and ultimately the patient will reach a stage of acceptance.

4. DISCUSSION

An intense search has been carried out to find published studies related to the phenomenon in our study. However no phenomenological study that investigated the phenomenon of disclosing truth about the diagnosis of cancer to the patients in Oman was found. The literature review showed that most of the studies related to disclosure of the truth about the diagnosis of cancer to the patients were quantitative. The current phenomenological study explored the phenomenon of disclosure of the truth about the diagnosis of cancer to the patients from a general perspective in order to provide an understanding of the participants’ lived experiences and perceptions of this phenomenon in Sultanate of Oman. All the participants shared almost the same emotional reactions, which ranged from emotional sadness when they discover the diagnosis of cancer in their patient to the positive feeling when the patient had got a positive response to the management. In addition, the emotional reaction of the patients when they received the news of the diagnosis of cancer revealed a normal human reaction to any bad news. Participants’ descriptions of their experiences with breaking bad news to the patient when they discovered the diagnosis of cancer showed a wise gradual approach. In addition the participants pointed that there is a lack of education and a need for more training both for the health care provider and for the public especially in the area of the medical ethics in general and in the area of ethics veracity in particular. In examining the literature in relation to the disclosure of the truth about the diagnosis of cancer to the patients and of ethics of veracity in health care. Perceptions and lived experiences descriptions collected in this study illustrate that all the participants have the same attitudes toward the preference of telling the patient the truth and this is consistent with the attitudes in the US which became a trend in the ensuing decades in clinical practice. The duty to disclose has now become formally codified in written ethical guidelines and informally grounded in contemporary Western biomedical ethics [19]. This may indicate the effect of their training in the North America upon their practice in Oman at SQUH. Omani physicians also believed in the patient rights to have correct information about his condition, the management plan in which they must consent in order to prepare himself from the Islamic point of view for any commitment they have to do before death [19]. Participants in this study strongly opposed to withholding information about Diagnosis, treatment and prognosis from the patients. They described the difficulties associated with caring for a patient, who was seemingly unaware of the diagnosis. Also they believe that Lying and deception in the clinical context is just as bad as continued aggressive interventions. In the end, both are qualified as torture. This is consistent with the finding of the study done by [20,21] Al-Amri’s study conducted the research on the patient in which he concluded that all of the patients rejected the idea of treatment without knowing their diagnosis and had a strong desire to know about the treatment, which also consisted with our study [14]. The participants questioned about the effectiveness of hiding a diagnosis and provided examples of patients suspecting the diagnosis and directly asking for more Information. This result is consistent with the finding of the study done by Kendal, 2002 [22]. Withholding information produced adverse results, given that it increased the stress and the uncertainty of the patients and this is consistent with Meredith et al., 1996 [23]. This in contrast with the finding of study done in Croatia (by Blazekovic-Milakovic et al., 2006 [24]) in which the majority delivered a cancer diagnosis occasionally, which is still the attitude in East of Europe. Empathetic communication is needed and this is consisted with the study done by Lee & Wu, 2002 and Buken, 2003 [6,25]. The strategy of breaking bad news was a stepwise Gradual consistent with Wood et al., 2009 & Lee & Wu, 2002 [19,25]. Although recently a new module in the Curriculum of the medical school in SQU About communication, still the participant Felt that the physicians needs more training in the field of breaking bad news Especially to cancer patients. And this is consisted with the study done by Wood et al., 2009 [19]. The cultural attitude in Oman is still a challenge to the physician because of the attitudes. Of the relatives and their frequent interfering and insist on treating the patient without telling him/her the truth about the cancer diagnosis, prognosis and treatment, which is similar to the finding of the study done in Saudi Arabia by Al-Amri, 2009 [14]. Overwhelmingly participants strongly disagreed with the Patients relatives request or demands to withhold information from patients and did provide the patient, all the information he needs to know, which was consistent with the study of Kendall, 2006 and Asai, 1995 [22,26]. This in contrast to what is the practice in Japan and in Singapore in which the Physician almost reveal the diagnosis of cancer to the family before telling the patient 84% will accede the family request not to tell the patient a study done in Singapore (Tan et al., 1993 [27]). In regard to the emotional side of the experience on the physician is consisted with the study of (Ten et al., 1993 and Blazekovic-Milakovic et al., 2006 [24,27]) who discover that the diagnosis of terminal illness often leave the physician with a sense of unease and helplessness. One of the important finding in this study the role of the social workers in our countries still not clear to the patients, physicians, nursing staffs and the managers, however many studies and researches and this is consisted with the study of Al-Qrni, M Musfer, Al-sayis, Amal & Shaikh Bawazeer, Zainab, 2009 [28] which confirmed the importance of the presence of specialist in medical social work specialized in all centers that treat the cancer. Social workers are trained to recognize and assist with the psychosocial needs of cancer patients and their families. They have the knowledge and skills required to assist cancer patients and their families with emotional, practical, and administrative issues in a variety of ways [29- 31].

5. THE LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

In this study there are some limitations: first, that the results present only physicians’ perspectives on the cancer disclosure question and so may miss pertinent perspectives of others such as family members, nurses. The second is the female gender has not included, because of the paucity of females on department of hematology and oncology prevented examination of differences in physician practice by gender, the third is sample size of this research was small, though this was driven by the end point of saturation.

6. CONCLUSIONS

The paucity of research on the subject is of concern and highlights the importance of the proposed research topic. Telling the truth to the patient is becoming more important if only to maintain the patient autonomy. This project will make a significant contribution to the ongoing discussion regarding this expanding area of health care practice and to the development of policies and procedures for encouraging physicians. Phenomenological studies do not necessarily lead to generalization of findings, but can help us to understand deeply the human lived experience.

The findings of the study suggests five important issues: 1) Appropriate measures and guidelines on the subject of truth telling and medical ethics must be taken from a national perspective in order to enhance the quality of healthcare provider to help them to handle any ethical dilemma and to increase the awareness of the people in the public. beside building up an official guidelines in the hospital setting on the subject of truth telling there is however no doubt that the doctors in Oman would welcome and probably benefit from these forms of guidelines on the subject by a competent committee; 2) The health care providers needs more training to increase their communication skills especially in the context of breaking bad news in telling the patient the truth about cancer diagnosis or any other serious illness, such skills have been found to improve Doctor-patient relationship, satisfaction with care and patient health outcomes; 3) There is a need to establish medical social work departments in SQUH, and also in the other Omani healthcare institutions and even perhaps all healthcare institutions in all Gulf States, being of similar culture as a separate section to support the treating teams in the hospital. Especially in the context of disclosing information to the patient; 4) The basic ethical principles of Islam relevant to medical practice must be added in the curriculum of medical colleges to enhance the ethical education during the undergraduate medical training or as continuous medical education as well; 5) Disclosing the information to the cancer patient is a team work job of the health care providers, the social worker must be an essential part of this team and the senior physician can be the leader of this team.

![]()

![]()

REFERENCES

- Surbone, A., Ritossa, C. and Spagnolo, A.G. (2004) Evolution of truth-telling attitudes and practices in Italy. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology, 52, 165-172. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2004.09.002

- Farzaneh, Z. and Bagher, L. (2007) Cancer ethics from the Islamic point of view. Iranian Journal of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology, 6, 17-24.

- Tatsuo, A., Tomohito, N., Hitoshi, O., Seiko, U., Nobuya, A., Tatsuro, N., et al. (2001) Psychiatric disorders in cancer patients: Descriptive analysis of 1721 psychiatric referrals at two Japanese cancer center hospitals. Japanese Journal of Clinical Oncology, 131, 188-194.

- Alexander, P.J., Dinesh, N. and Vidayasagar, M.S. (1993) Psychiatric morbidity among cancer patients and its relationship with awareness of illness and expectations about treatment outcome. Acta Oncologica, 32, 623-626. doi:10.3109/02841869309092441

- Atesci, F.C., Baltalarli, B., Oguzhanoglu, N.K., Karadag, F., Ozdel, O. and Karagoz, N. (2004) Psychiatric morbidity among cancer patients and awareness of illness. Supportive Care Cancer, 12, 161-167. doi:10.1007/s00520-003-0585-y

- Buken, N.O. (2003) Truth telling information and communication with cancer patient in turkey. Journal of the International Society for the History of Islamic Medicine, 2, 31-37.

- Beauchamp, T.L. and Childress, J.F. (2009) Principles of biomedical ethics. 6th Edition, Oxford University Press, New York.

- Sokol, D.K. (2006) Truth-telling in the doctor-patient relationship: A case analysis. Clinical Ethics, 1, 000-100.

- Baider, L. and Surbone, A. (2010) Cancer and the family: The silent words of truth. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 28, 1269-1272. doi:10.1200/JCO.2009.25.1223

- Hébert, P.C., Hoffmaster, B., Glass, K.C. and Singer, P.A. (1997) Truth telling. Bioethics for clinicians. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 156, 225-228.

- Elkin, E.B., Kim, S.H., Casper, E.S., Kissane, D.W. and Schrag, D. (2007) Desire for information and involvement in treatment decisions: Elderly cancer patients’ preferences and their physicians’ perceptions. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 25, 5275-5280. doi:10.1200/JCO.2007.11.1922

- Searight, H.R. and Gafford, J. (2005) Cultural diversity at the end of life: Issues and guidelines for family physicians. American Family Physician, 71, 515-522.

- Gordon, M. and Marcia, S. (2005) Protection from the truth: A challenge for surrogates and health care professionals. Annals of Long-Term Care, 13, 10-11.

- Al-Amri, A.M. (2009) Cancer patients’ desire for information: A study in a teaching hospital in Saudi Arabia. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal, 15, 19-24.

- Mobeireek, A.F., Al Kassimi, F., Al Zahrani, K., Al Shimemeri, A., Al Damegh, S., Al Amoudi, O., et al. (2008) Information disclosure and decision-making: The Middle East versus the Far East and the west. Journal of Medical Ethics, 34, 225-229. doi:10.1136/jme.2006.019638

- Van Manen, M. (1990) Researching lived experience: Human science for an action sensitive pedagogy. State University of New York Press, Albany.

- Blau, R., Bolus, S., Carolan, T., Kramer, D., Mahoney, E., Jette, D.U. and Beal, J.A. (2002) The experience of providing physical therapy in a changing health care environment. Physical Therapy, 82, 648-657.

- Lane, M.R. (2005) Spirit body healing—A hermeneutic, phenomenological study examining the lived experience of art and healing. Cancer Nursing, 28, 285-291. doi:10.1097/00002820-200507000-00008

- Wood, W.A., McCabe, M.S. and Goldberge, R.M. (2009) Commentary: Disclosure in oncology—To whom does the truth belong? The Oncologist, 14, 77-82. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2008-0158

- Soler, D. (2005) Telling patients the truth. Malta Medical Journal, 4, 56.

- Drane, J.F. (2002) Honesty in medicine: Should doctors tell the truth? American Journal of Bioethics, 2, 14-17.

- Kendall, S. (2006) Being asked not to tell: Nurses’ experiences of caring for cancer patients not told their diagnosis. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 15, 1149-1157. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01460.x

- Meredith, C., Symonds, P., Webster, L., Lamont, D., Pyper, E., Gillis, C.R., et al. (1996) Information needs of cancer patients in west Scotland: Cross sectional survey of patients’ views. British Medical Journal, 313, 699- 700. doi:10.1136/bmj.313.7059.724

- Blazeković-Milaković, S., Matijasević, I., Stojanović-Spehar, S. and Supe, S. (2006) Family physicians views on disclosure of a diagnosis of cancer & care of terminally ill patients. Psychiatria Danubina, 18, 19-29.

- Lee, A. and Wu, H.Y. (2002) Diagnosis disclosure in cancer patients—When the family says “no!”. Singapore Medical Association, 43, 533-538.

- Asai, A. (1995) Should physicians tell patients the truth? The Western Journal of Medicine, 163, 36-39.

- Tan, T.K.S., Teo, F.C.P., Wong, K. and Lim, H.L. (1993) Cancer: To tell or not to tell? Singapore Medical Journal, 34, 202-203.

- Musfer, A.M., Amal, A. and Zainab, S. B. (2007) Social work and patient with cancer. Daar Al-Rushid, AL-Riyadh, 3, 27.

- Gadalla, T.M. (2007) Cancer patients’ use of social work services in Canada: Prevalence, profile, and predictors of use. Health & Social Work, 32, 189-196. doi:10.1093/hsw/32.3.189

- Gregorian, C. (2005) A career in hospital social work: Do you have what it takes? Social Work in Health Care, 40, 1-14. doi:10.1300/J010v40n03_01

- Christ, G. and Blacker, S.E. Palliative care with older adults, section 2: Social work role in palliative care. Council on Social Work Education, National Center. http://www.cswe.org/File.aspx?id=24173