Sociology Mind 2012. Vol.2, No.1, 80-86 Published Online January 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/sm) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/sm.2012.21011 8 0 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. Deconstructing the Glass Ceiling Carol A. Isaa c1, Anna Kaatz1, Molly Carnes1-5 1Center for Women’s Health Research, University of W isc on sin -Madison, Madison, USA 2Departments of Medicine , Psychiatry, Unive rsity of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, US A 3Industrial & Systems Engineering, Psychology, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Mad ison, USA 4Women in Science and En gineering Leadership Institute, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, USA 5William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital, Madison, USA Email: cisaac@wisc.edu Received August 9th, 2011; r evised September 20th, 2011; accepted N ovember 1st, 2011 Aims: There is a large body of evidence-based research illustrating the challenges faced by women who strive in male-typed careers. The purpose of this paper is to outline and integrate a review of the relevant social psychology research into a model of women’s leadership. Proposed Conceptual Argument: As leadership is stereotypically a masculine dimension, women who emulate agentic characteristics will rise into leadership. However, empirical evidence overwhelmingly illustrates the consequences to agentic women whose competence is simultaneously expected and minimized. Findings/Conclusion: This model raises awareness of complex issues in research for women including: the “promotion of ‘male’ females”, “success does not equal competence”, “agentic women sustain reactive opposition”, “the process of self-selection”, “stereotypic threat”, and “equality equals greed”. Because of the ubiquity of these cogni- tive distortions, awareness may mitigate antagonism and conflict to propel women into leadership roles. Keywords: Glass Ceiling; Leadership; Gender; Model; Women; Deconstruction Introduction Leadership is a performance of power that signifies male- type or agentic character traits such as “independence” and “action”. One identified contributor to women’s slower than expected assent into leadership in academic Science, Technol- ogy, Engineering, Mathematics and Medicine (STEMM) is the persistence of assumptions and stereotypes that women are intrinsically “communal” or “dependent” and “passive”, and ther e- fore, lack the capacity to succeed as leaders (National Academy of Sciences National Academy of Engineering Institute of Medicine of the National Academies, 2006). Stereotype- based cognitive biases about gender contribute to women’s underrep- resentation in professions traditionally occupied by men, such as academic STEMM in multiple ways: they influence women’s self-beliefs, causing them to self-select out of highly agentic roles such as leadership; they also disadvantage women in re- view processes critical for advancement—women are under- rated in evaluation processes for leadership roles even by indi- viduals who consciously hold egalitarian beliefs (Hill, Corbett, & St. Rose, 2010; Valian, 1998). Despite policy changes such as Title IX of the Civil Rights Act (1972) in the US and interna- tionally, the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW, 1979) and the Bei- jing Platform for Action (1995), women and men still do not enjoy equal opportunities for education, employment, success, advancement, and satisfaction. Because most people are unaware of implicit biases and how they work to disadvantage women in leadership, their effect has been attributed to “a glass ceiling”, a metaphor describing in- visible barriers to women’s career advancement (Loden, 1996). In this sense the reason why women do not advance beyond a certain level in organizations is not readily apparent; upon closer inspection a ceiling is revealed—made up of biased judgments women collectively experience as they work to ad- vance. Significant empirical research has mapped the “glass ceiling” and its landscape of implicit socio-cultural and psy- cho-social barriers to women’s full participation in academic STEMM and other male-typed occupations; however, a femi- nist theoreti cal lens has not yet been applied to deconstruct this body of work. What remains unaddressed, in particular, is the extent to which the empirical research used to map causal rea- sons for women’s under-representation may function to inad- vertently reinforce the very power structures that recreate belief in gender difference and the assumption that leadership is a male trait. This paper problematizes [applies a critical lens to] that body of literature and proposes a unique, feminist model of leadership. Social Role Theory: A Framework for Empiricism about Gender Bias Based upon empirical studies from the fields of social and cognitive psychology Figure 1 represents six major barriers women face (i.e., six panels of the glass ceiling) as they work to advance to leadership in male-typed jobs. Throughout this body of research social role theory is used to explain the contempo- rary causes of belief in gender difference. According to social role theory individuals learn to associate specific traits and characteristics with men and women based upon the types of work they have traditionally performed, differentiating these beliefs about gender roles into “communal” versus “agentic” attributes (Eagly, 1987; Eagly & Karau, 2002; Eagly, Mitchell, & Paludi, 2004). The vertical arrow in the model represents the hierarchical nature of power and characteristics defining leadership. The  C. A. ISAAC ET AL. Figure 1. Map of the glass ceiling. Bem Sex Role Inventory, an instrument developed by both men and women participants and validated over several decades, characterizes “leadership abilities” as a masculine trait (Bem, 1974; Holt & Ellis, 1998). These studies identify the tenacious stereotypic merging of the male gender with leadership traits: confident, tough, dominant, assertive, instrumental, controlling, self-sufficient, ambitious, aggressive, forceful, independent, competitive and “prone to act like a leader”; while communal characteristics, ascribed primarily to women, describe concern for other’s welfare including being “affectionate, helpful, kind, sympathetic, interpersonally sensitive, nurturant, and gentle” (Bem, 1974; Eagly & Karau, 2002). These feminine traits have little overlap with those ascribed to the stereotypical leader. An early study by Broverman and colleagues found that male- gendered traits were highly valued and constituted a compe- tency cluster which was assumed to be antithetical to and in- compatible with femininity (Bro verman, 1972). Though it has been highly debated, there is no definitive sci- entific evidence that men and women differ in their ability to learn or perform agentic (e.g., logic, leadership) or communal (e.g., mentoring, caretaking) tasks (Hyde, 2005; Plant, Hyde, Keltner, & Devine, 2000). Despite this information, cultural attitudes, assumption and stereotypes about gender difference persist and operate to prescribe and instruct both individuals’ self-beliefs as well as social norms and ideas about the ‘natures’ of men and women and how they should behave. As women work toward leadership in agentic or male-typed jobs, in par- ticular, social role theory predicts that they will face disadvan- tage due to a “lack of fit” between the communal traits they are both assumed and expected to have, and the agentic traits asso- ciated with success and competence in those jobs. This hy- pothesis has been tested repeatedly through empirical studies and Figure 1 provides an outline of constructs from research findings that illustrates the specific barriers—or glass ceiling— women encounter as they work toward leadership in male-type professions. In much of the literature, the discrimination faced by women is not differentiated between explicit and implicit bias. In a systematic review of experimental evidence for interventions that affect implicit gender bias in employment, in 24 of 27 arti- cles, mal e and female part icipants did not differ in their evalua- tions of women. The fact that empirical studies show that both genders propagate implicit bias circumvents the “us” versus “them” polarities that permeate the literature. Placing the em- phasis on “we” rather than “them”, mitigates the oppositional counterculture deconstructs the binary of gender (Kristeva, 1995; Snyder, 2008). Deconstruction “unmasks the supposed ‘truth’ or meaning of text by undoing, reversing, and displacing taken-for-granted binary oppositions that structure texts (e.g., right over wrong, subject over object, reason over nature, men over women, speech over writing, and reality over appearance)” (Schwandt, 2001). Feminism provides a “necessary moment of reversal”, to purge the system of its present masculinist he- gemony, yet adding the perspective that both sexes are equally guilty of implicit bias helps deconstruct the “masculine/feminine schema” (Caputo, 1997). This paper seeks to uncover a “re-rever- sal” of women under the glass ceiling, looking at their own re- flections. Piecing Together Empirical Research The center of the model (Figure 1) represents women’s iden- tity with the intersection of the unconscious barriers of implicit gender bias. The barrier in frame 1 titled, Agentic Equals Suc- cess, represents the way that stereotypical male-gendered agen- tic traits are more highly valued in our society than stereotypi- cal female-gendered communal traits (O’Heron & Orlofsky, 1990; Rudman & Glick, 1999). Though women are socialized and expected to behave in communal ways, both men and women who display agentic instead of communal behaviors are viewed as more competent in male sex-typed jobs (Carli, 2001; Cuddy, Fiske, & Glick, 2004; Heilman, Wallen, Fuchs, & Tamkins, 2004; Rudman & Glick, 1999). In addition, women who display more stereotypical male, or at least androgynous leadership characteristics, are more likely to gain access to leadership especially in male sex-typed positions (Francesco & Hakel, 1981; McConnell & Fazio, 1996; Rudman & Glick, 1999, 2001). An immediate issue women face as they embark upon male-typed jobs, therefore, is the need to be highly agen- tic; this may contradict with their own self-beliefs as well as the expectations of the cultures in which they live. As a result women may self-select out of these jobs, or feel less inclined to seek promotions, or high ranking and leadership positions. The second barrier, Success ≠ Competence, represents the way that when gender stereotyping is activated, raters are less likely to attribute a woman’s success to ability than a man’s success. This attributional rationalization results from the as- sumption that men are more competent than women (Deaux & Emswiller, 1974; Heilman & Haynes, 2005; Swim & Sanna, 1996). Stereotyping effects are usually contextually assimila- tive as a group member stereotyped as having some attribute (i.e. men have leadership skills) is judged to have more of that attribute than a member of some comparison group (Biernat, 2003). Biernat found that gender stereotypes regarding task competence led decision makers to set different standards for judging competence in women versus men. More specifically, stereotyping may create lower minimum standards for initial hiring screens for women but higher confirmatory standards for women than men, so women would be more likely to make a short list, but would be less likely to be hired (Biernat & Fuegen, 2001). Because of the attributional rationalization related to gender and competence, when there is ambiguity in performance crite- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 81  C. A. ISAAC ET AL. ria, evaluations of women’s competence in male sex-typed jobs may be negatively affected (and men’s positively affected). In summarizing a wide range of research on gender and career advancement, Valian (1998) notes that as a woman rises into the top tiers of leadership, the mere fact that she is successful leads people to see her as succeeding against expectations, at- tributing her success to luck, the task being easy, or to working hard rather than competence. Women as managers gain status attribution which creates connotations of instrumental compe- tence; however, a woman will still be seen as less competent than a male manager with similar characteristics (Ridgeway, 2001). Heilman & Haynes (2005) found that women working as part of a mixed-sex dyad received less credit than men even for identical work for stereotypically male tasks unless their contribution was made explicit to the raters. Stereotype-based expectations are tenacious and are resistant to disconfirming information. Competent women may interpret receiving less credit on a task as failure or may get angry at feeling ignored. Brescoll and Uhlmann (2008) found that the expression of anger by an applicant improved men’s evalua- tions and lowered women’s, particularly women in a high status position. Having a specific external cause (such as losing an account) for anger mitigated but did not eliminate the negative bias toward women (Brescoll & Uhlmann, 2008). Even though external attribution for anger improved status and salary ratings for women who expressed anger, it had no impact on their lower competence rating. Women who are competent in male sex-typed roles may produce negative reactions (Glick, Larsen, Johnson, & Bransititer, 2005) and lower ratings simply because their competence violates the prescriptive norms for female behavior (Heilman & Okimoto, 2007). This appears to be par- ticularly true for women who exhibit anger, considered a male emotion (Plant et al., 2000). Unfortunately, anger compounds women’s problems if they react to the stereo-typical assump- tions of men’s superior competence. The third barrier, Agentic → Reactive Opposition, illustrates that women who display agentic traits (not including anger) and are clearly competent in masculine sex-typed positions will be deemed as competent as men, but are viewed as less likeable and hostile than successful men. Independent of competence, likeability predicts advantage in career-affecting outcomes in evaluation and reward allocation (Heilman et al., 2004). As highly agentic women assert authority outside of traditionally female sex-typed jobs, they are likely to encounter reactive opposition to their authority (Ridgeway, 2001). Women appear to be able to reduce this opposition by “softening” assertive, competent behaviors to increase their influence and negotiate beyond the predicted gender constraints on their social power (Carli, 2001). Heilman and Okimoto (2007) found that provid- ing clear evidence of communality in the workplace (e.g. sensi- tive to the needs of his/her staff) had no effect on the ratings of fictional male leaders but improved women’s ratings of likabil- ity above those of equivalently competent men and equalized assessments of boss interpersonal hostility for men and women. Negativity toward competent women can also be mitigated for those who show evidence of being homemakers, mothers, or volunteers in areas of social need-representations of female- gendered behavior in the male context of leadership (Drogosz & Levy, 1996). Correll et al. (2007) experimentally manipu- lated parenthood in employment-related ratings and found that motherhood penalized women applicants on perceived compe- tence and starting salary whereas fatherhood benefited men (Correll, Benard, & In, 2007). Moreover, while successful women in male-sex typed roles (such as being a leader) appear to face negative consequences for violating gender-stereotypic prescriptions, women leaders can also be penalized if they do not show clear evidence of work-related communality or if they show too much non-work related communality by being a mother. This balancing act between agentic and communal behaviors continually requires adaptability and adjustment- negotiating behaviors not traditionally required of men. The fourth barrier, Parenthood & Self-Selection, illustrates that the issues for women are not research or teaching, but par- enting and mobility as a cause for self-selection away from academia (van Anders, 2004). A recent critical review of the literature representing women’s underrepresentation in mathe- matically intensive scientific fields concluded that the evidence supporting a biological difference in mathematical ability be- tween men and women is contradictory (Ceci, Williams, & Barnett, 2009). The conclusion of this review is further sup- ported by Mason and Goulden (2004) in a nationally represen- tative sample of PhDs (Mason & Goulden, 2004). They found that women who successfully pursue academic careers are less likely to marry and have children and more likely to divorce, than men who succeed in academic careers or women who drop out of the pipeline to tenure. This study revealed that factors affecting women’s success “spill over into the family, or the reverse, the family spills over into the job” (Ceci, Williams, & Barnett, 2009). As poignant and compelling as parenthood responsibilities are to women, there are other implicit sociocultural reasons why women do not advance or remain in leadership. When women deviate outside the cultural norm, they may self-select and avoid managerial positions that seem threatening to a sense of what a women’s identity in society should be. For example, Brunner found that women superintendents were uncomfortable using power over other people (Collard & Reynolds, 2005), and so it may not be success per se that many women fear, but rather the behaviors that lead to success may not meet with the approval of others (Austin, 2000). Chusmir and Koberg (1991) examined the self-confidence and sex-role identities of male and female managers, and found that sex-role identity (but not gender) was a major factor in the level of self-confidence. Their results showed that women and men in jobs that produced cross-sex role identities had lower levels of self-confidence; gender was not a factor in level of self-confidence, but those with masculine or androgynous ori- entations had higher self-confidence (Chusmir & Koberg, 1991). Depending on the culture of the organization and the woman leader’s identity-orientation, there is evidence that women may experience discomfort when crossing into masculine sex-typed jobs. Although Morley (2006) reported that attributing difficulties to women’s psychic narratives (such as lack of confidence) contributes to a theory of deficit rather than a theory of power, it is important to recognize that the implicit nature of bias strikes the internal mechanisms of women. This kind of aware- ness and consciousness-raising is the first stage in the applica- tion of behavioral change (Prochaska, Prochaska, & Levesque, 2001; Prochaska & Velicer, 1997). The fifth barrier, Stereotypic Threat & Identity Safety, il- lustrate that stigmatized individuals are aware of accusations that devalue their group’s social identity as women are typically stereotyped as being emotional and lacking leadership aptitude 8 2 Copyright © 2012 SciRes.  C. A. ISAAC ET AL. (Crocker et al., 1998). This leads to what Claude Steele’s group has termed “stereotypic threat”. The stereotype that women are not as good leaders as men can produce a threat that can poten- tially undermine performance and aspirations among women (Davies, Spencer, & Steele, 2005; Steele, 1997). Women are vulnerable to stereotypic threat in traditionally masculine do- mains that allege a sex-based inability (Crandall, Eshleman, & O’Brien, 2002; Davies, Spencer, Gallagher, & Kaufman, 2005; O’Brien & Crandall, 2003; Spencer, Steele, Quinn, Hunter, & Forden, 2002). In a study specific to leadership, participants were exposed to gender-stereotypic TV commercials and then given a choice between being a leader or supporter. Women participants be- came vulnerable to stereotypic threat that led women to avoid leadership roles in favor of supportive roles (Davies, Spencer, & Steele, 2005). However, the researchers created “an identity- safe” environment as an intervention by including a sentence confirming that research indicates no gender difference in abil- ity to perform as a leader or problem solver (the more subordi- nate role). The inclusion of such a statement eliminated the vulnerability to stereotypic threat despite exposure to threaten- ing situational cues that primed stigmatized social identities. Although here are many studies that document stereotypic threat, this study’s hallmark is that it provided an intervention that successfully restored women’s leadership aspirations. Stereotypes can be combated or changed by using the same tools that propagated these cognitive distortions of reality. The sixth barrier, Equality Equals Greed, illustrates the power of social norms. There have been several studies con- ducted where results showed that men as compared to women: evaluate their performance more favorably, despite comparable scores; claim greater ability following performance on tasks; and are less prone to explain successful performance as due to luck although both sexes did not differ in attributions to luck, effort, or task (Cherry & Deaux, 1978; Correll, 2004; Deaux, 1979, 1995; Deaux & Emswiller, 1974; Deaux & Farris, 1977). These gender differences on performance evaluations are high- est in response to failure on masculine tasks. Women medical students rated themselves lower than their male counterparts on all measures of academic ability as well as future performance as a physician; men were likely to persist until there was no possibility of success while women persisted only until there was some possibility of failure (Fiorentine, 1988). This research offers explanations that the transgression of gender norms pro- vides women incentives to change or lower their high-status career goals when encountering hardship, self-doubt, and the possibility of failure (Fiorentine & Cole, 1992). In a more re- cent study, researchers found that female physicians’ self-effi- cacy for 34 out of 35 competencies required to succeed as an independent clinical investigator were lower than male physi- cians following a 3-day workshop on clinical research in which all the faculty presenters were men (Bakken, Sheridan, & Carnes, 2003). As there are gender-differentiated double stan- dards how men and women attribute performance to ability, men and women will also form different aspirations for career paths because of their own competence beliefs (Correll, 2004). In a study of discrepancies in pay expectations of male and female management students, females had significantly lower career-entry and career peak pay expectations. Gender differ- ences in career paths, comparison standards, and position im- portance were identified as potentially important explanations as women undervalue the financial worth of their work (Major & Konar, 1984). In studies of perceived pay entitlement, women allocate themselves less pay than do men especially when their experience is not made specifically relevant to the decision (Desmarais & Curtis, 1997; Major, Shaver, & H en dric k, 1987). There are strong social mores against self-promoting women as women suffer social reprisals for violating the gender prescription of modesty (Rudman, 1998). Although Blackmore (2007) found that self-promotion was central to the managerial performative culture, women in her study found it difficult to violate the social norm of modesty. Mod- esty may create self-sabotage at critical career junctures. Re- peatedly, women demonstrate that their perception of entitle- ment interprets “equality as greed” as men take more for themselves that women do (Valian, 1998). An affirmative action study conf irmed that while wome n believe men receive unfair benefit, men believe women are responsible for their own disadvantage (Boeckmann & Feather, 2007). While women may not be responsible for conscious and unconscious discriminatory practices, women are responsible for becoming aware of self-abnegating behavior and seeking constructive solutions. Discussion: “It’s Not about You or Them” This review illustrates the complexities that affect the identi- ties of women leaders. Stereotypical male-gendered agentic traits are more highly valued in our society than stereotypical female-gendered communal traits (O’Heron & Orlofsky, 1990; Rudman & Glick, 1999), and women who display agentic vs communal behaviors are viewed as more competent in male sex-typed jobs (Carli, 2001; Cuddy et al., 2004; Heilman et al., 2004; Rudman & Glick, 1999). However, as highly agentic women assert authority outside of traditionally female sex- typed jobs, they are likely to encounter reactive opposition to their authority as they are less liked (Ridgeway, 2001). Provid- ing clear evidence of communality in the workplace improved women’s ratings of likability (Heilman & Okimoto, 2007), but women applicants who are mothers were penalized on per- ceived competence and recommended starting salary. As wo- men are perceived as competent, others will label their success as those who just do “easy tasks” or such hard workers that they are “over-achievers” (Swim & Sanna, 1996; Valian, 1998). Women and men in jobs that produced cross-sex role identities had lower levels of self-confidence. Stereotype threat may un- dermine performance and aspirations among women in the absence of identity-safety. There are strong social mores against self-promotion which is also evident for women at the highest leadership levels (Bligh & Kohles, 2008). This model repre- sents the cognitive distortions illustrated from empirical evi- dence derived primarily from social psychology that influence women’s identities in leadership. The proposed model for women’s leadership attempts to ex- plain the interplay of tensions effecting women’s identities (although these constructs may also affect men whom imple- ment non-linear leadership styles). Julia Kristeva, a French psychoanalyst with a focus on women’s identity, suggests that the danger of binary opposition is the creation of a countercul- ture, because “by fighting against evil, we reproduce it, this time at the core of the social bond—the bond between men and women” (Kristeva, 1995: p. 214). This sociopsychic splitting of identity must arise when women operate within this hierarchical, masculine model (Blackmore & Sachs, 2007). In addition, Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 83  C. A. ISAAC ET AL. leadership has been associated with an assumed capacity to change oneself into a leader (Blackmore & Sachs, 2007), while others have suggested that women are deficit and lacking lead- ership qualities (Morley, 2006). Both concepts may be a rendi- tion of “fix the women” (Carnes, Morrissey, & Geller, 2008) as women “assimilate” into the male-dominated, hierarchical role of leadership (Isaac, 2007). Women in leadership positions assimilate into a masculine world. If women self-select from leadership opportunities, the call for policies to address social concerns of women will di- minish. “Family-friendly” workplace policies such as job shar- ing do exist, but pose long-term risk to careers and are consid- ered dangerous as women who admit to care-giving responsi- bilities are penalized more than men (Drago et al., 2005; Jacobs & Gerson, 2004). The catch-22 is that leadership roles may require assimilation and yet, if women avoid leadership oppor- tunities, the less likely that women will ascend into leadership and promote women’s accessibility (Bagilhole, 1993; Rudman & Glick, 2001). It is important to raise awareness of the implicit nature of bias that strikes the internal mechanisms of women as these have become habitual in individuals’ responses directed toward women. In much of the literature, the focus is on the discrimi- nation faced by women with little differentiation between ex- plicit and implicit bias. Knowledge that both genders propagate discrimination circumvents the “us” versus “them” polarities. Placing the emphasis on “we” rather than “them”, mitigates the binary of opposition which collapses the category of “women”. Knowing also of the reaction against “angry women”, women who have awareness of the ubiquity of bias from both men and women (including themselves) may also be given the gift of perspective and empathy-deconstructing gendered polarities. Research has shown that perspective taking inspires empathy arousal and this leads to improved intergroup attitudes and that encouraging a perceiver to adopt a perspective of another eliminates perceived difference (Batson et al., 1997; Galinsky & Moskowitz, 2000; Vescio, Sechrist, & Paolucci, 2003). While this research primarily focuses on “other’s” attitudes, another possibility derived from this research is that women’s experiences of discrimination becomes not all about “them- selves” but also not all about the “other”. If “resilience has been defined as the capacity of dynamic systems to withstand sig- nificant disturbances” (Masten, 2007); then mitigating per- ceived opposition promotes positive outcomes for women in challenging circumstances. Conclusion The goal of this paper is to integrate the empirical evidence and bring into high relief the variety of challenges women face in seeking or taking on leadership roles in organizations. Bas- ing conclusions on evidence is highly relevant to women scien- tists. This model attempts to make this research readable to the STEMM community, as feminist text too can exclude other meanings and stabilize “meaning within a system of power relations-a system of inclusion and exclusion” (Calás & Smir- cich, 1999: p. 654). Limitations include the inability to take into account changes in historical, cultural, class, ethnic, contextual and political factors and creating a “homogenous” essentialist view of wo- men. Many of the experimental studies used did not differenti- ate between these other factors and so these were not included in the model. Also homogeneity is one of the characteristics of implicit bias which was the focus of this paper. And while some men may experience some of these constructs, these arti- cles focus on women. There are inherent difficulties when blending the essentialism of experimental evidence with post- modern research, yet there are valuable perspectives gained in examining conflicting discourses and expanding the conversa- tion (Martin, 1985). Finally, this problem has remained persistent within higher education institutions that have long been credited with im- proving social and cultural problems. Clearly, policies and pro- cedures attempt to address explicit forms of discrimination; however, there has been concern that policies to combat gender marginalization has been reduced to technology toolkits and “how-to” checklists (Morley, 2007). Moreover, equity policies can sometimes create reactive backlash (Isaac, Lee, & Carnes, 2009; Morley, 2006). There are change models from social psychology that help to illustrate the psychological and behav- ioral changes women experience as they enter leadership roles (Devine, 1989, 2001; Overton, McCalister, Kelly, & Macvicar, 2009; Plant & Devine, 2009; Prochaska et al., 2001; Prochaska & Velicer, 1997). Prochaska, in a study to advance women scientists, called for interventional strategies to increase women’s self-efficacy and self-confidence (Prochaska et al., 2006). Di- rections for future research may include interventional strate- gies at the organizational and individual levels to address these issues. Providing evidence of the ubiquity of implicit bias to women neutralizes polarities that stress the social bond between men and women. This review of the extant experimental re- search suggests that work needs to be done at the individual level. As leadership is stereoty pically a masculine dimension, wo me n who emulate those characteristics of assertiveness will rise into leadership. As women leaders negotiate career demands, they also struggle with assimilating into a masculine context that is riddled with contradictions. Instead of reproducing a counter- culture, the authors hope to give the gift of perspective regard- ing the contradictions affecting women’s identities in leader- ship. The empirical evidence overwhelmingly illustrates the consequences to agentic women whose competence is simulta- neously expected and minimized, actualizing a “failed assimila- tion” (Isaac, 2007). As leaders reach the pinnacles of their ca- reers, there is need for reflection, and this is especially true for women negotiating the masculine discourse of leadership. While the research can be disillusio n ing, we be lie ve t hat awar eness may segue into resilience. Acknowledgements We thank Barbara Lee, PhD for her input and editorial assis- tance on this manuscript. REFERENCES Austin, L. S. (2000). What’s holding you back?: 8 critical choices for women’s success (1st ed.). New York: Basic Boo k s. Bagilhole, B. (1993). How to keep a good woman down: An investiga- tion of the role of institutional factors in the proce ss of discrimination against women academics. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 14, 261-274. doi:10.1080/0142569930140303 Bakken, L. L., Sheridan, J., & Carnes, M. (2003). Gender differences among physician-scientists in self-assessed abilities to perform clini- cal research. Academic Medicine, 78, 1281-1286. 8 4 Copyright © 2012 SciRes.  C. A. ISAAC ET AL. doi:10.1097/00001888-200312000-00018 Batson, C. D., Polycarpou, M. P., Harmon-Jones, E., Imhoff, H. J., Mitchener, E. C., Bednar, L. L., & Highberger, L. (1997). Empathy and attitudes: Can feeling for a member of a stigmatized group im- prove feelings toward the group? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72, 105-118. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.72.1.105 Bem, S. (1974). The measurement of psychological androgeny. Journal of Consultation in Clinical Psychology, 42, 155-162. doi:10.1037/h0036215 Biernat, M. (2003). Toward a broader view of social stereotyping. American Psychologist, 58, 1019-1027. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.58.12.1019 Biernat, M., & Fuegen, K. (2001). Shifting standards and the evaluation of competence: Complexity in gender-based judgment and decision making. Journal of S ocial Issues, 57, 707-724. doi:10.1111/0022-4537.00237 Blackmore, J., & Judyth, S. (2007). Performing and reforming leaders: Gender, educational restructuring, and organizational change. New York: State University of New York Press. Bligh, M. C., & Kohles, J. C. (2008). Negotiating gender role expecta- tions: Rhetorical leadership and women in the US senate. Leadership, 4, 381-402. doi:10.1177/1742715008095187 Boeckmann, R. J., & Feather, N. T. (2007). Gender, discrimination beliefs, group-based guilt, and response to affirmative action for Australian women. Psycholo g y o f Women Quarterly, 31, 290-304. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2007.00372.x Brescoll, V. L., & Uhlmann, E. L. (2008). Can an angry woman get ahead? Status conferral, gender, and expression of emotion in the workplace. Psych ol og ica l Sc ie nc e, 19, 268-275. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02079.x Broverman, I. K. (1972). Sex-role stereotypes: A current appraisal. Journal of Social Issues, 28, 59-78. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.1972.tb00018.x Caputo, J. D. (1997). Deconstruction in a nutshell: A conversation with Jacques Derrida. New York: Fordham University Press. Carli, L. L. (2001). Gender and social influence. Journal of Social Issues, 57, 725-741. doi:10.1111/0022-4537.00238 Carnes, M., Morrissey, C., & Geller, S. E. (2008). Women’s health and women’s leadership in academic medicine: Hitting the same glass ceiling? [Review]. Journal of Womens Health, 17, 1453-1462. doi:10.1089/jwh.2007.0688 Ceci, S. J., Williams, W. M., & Barnett, S. M. (2009). Women’s un- derrepresentation in science: Sociocultural and biological considera- tions. Psychological B ull et i n , 135, 218-261. doi:10.1037/a0014412 Cherry, F., & Deaux, K. (1978). Fear of success versus fear of gen- der-inappropriate behavior. Sex Roles, 4, 97-101. doi:10.1007/BF00288380 Chusmir, L. H., & Koberg, C. S. (1991). Relationship between self-confidence and sex role identity among managerial women and men. Journal of Social Psychology, 131, 781-790. doi:10.1080/00224545.1991.9924665 Collard, J., & Reynolds, C. (2005). Leadership, gender and culture in education: Male and female perspectives. New York, NY: Maiden- head. Correll, S. J. (2004). Constraints into preferences: Gender, status, and emerging career aspirations. American Sociology Review, 6 9 , 93-113. doi:10.1177/000312240406900106 Correll, S. J., Benard, S., & In, P. (2007). Getting a job: Is there a motherhood penalty? American Journal of Sociology, 112, 1297- 1338. doi:10.1086/511799 Crandall, C. S., Eshleman, A., & O’Brien, L. (2002). Social norms and the expression and suppression of prejudice: The struggle for inter- nalization. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 359- 378. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.82.3.359 Crocker, J., Major, B., Steele, C., Gilbert, D. T., Fiske, S. T., & Lindzey, G. (1998). Social stigma. The handb ook of social p sychology, Vo ls. 1 and 2 (4th ed.) (pp. 504-553). New York, NY: McGraw- Hill. Cuddy, A. J. C., Fiske, S. T., & Glick, P. (2004). When professionals become mothers, warmth doesn’t cut the ice. Journal of Social Issues, 60, 701-718. doi:10.1111/j.0022-4537.2004.00381.x Davies, P. G., Spencer, S. J., Gallagher, A. M., & Kaufman, J. C. (2005). The Gender-gap artifact: Women’s underperformance in quantitative domains through the lens of stereotype threat. Gender differences in mathematics: An integrative psychological approach (pp. 172-188). N e w Y ork, NY: Cambridge University Press. Davies, P. G., Spencer, S. J., & Steele, C. M. (2005). Clearing the air: Identity safety moderates the effects of stereotype threat on women’s leadership aspirations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88, 276-287. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.88.2.276 Deaux, K. (1979). Self-evaluations of male and female managers. Sex Roles, 5, 571-580. doi:10.1007/BF00287661 Deaux, K. (1995). How basic can you be? The evolution of research on gender stereotypes. Journal of Social Issues, 51, 11-20. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.1995.tb01305.x Deaux, K., & Emswiller, T. (1974). Explanations of successful per- formance on sex-linked tasks: What is skill for the male is luck for the female. Journal o f P e rsonality and Social Psychology, 29, 80-85. doi:10.1037/h0035733 Deaux, K., & Farris, E. (1977). Attributing causes for one’s own per- formance: The effects of sex, norms, and outcome. Journal of Re- search in Personality, 11, 59-72. doi:10.1016/0092-6566(77)90029-0 Desmarais, S., & Curtis, J. (1997). Gender and perceived pay entitle- ment: Testing for effects of experience with income. Journal of Per- sonality and Social P s y c h o lo g y , 7 2 , 141-150. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.72.1.141 Devine, P. G. (1989). Stereotypes and prejudice: Their automatic and controlled components. Journal of Personality and Social Psychol- ogy, 56, 5-18. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.56.1.5 Devine, P. G. (2001). Implicit prejudice and stereotyping: How auto- matic are they? Introduction to the special section. Journal of Per- sonality and Social P s y c h o lo g y , 8 1 , 757-759. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.81.5.757 Drago, R., Colbeck, C., Stauffer, K. D., Pirretti, A., Burkum, K., Fazioli, J., & Habasevich, T. (2005). Bias a ga in st ca regiving. Academe, 91. Drogosz, L. M., & Levy, P. E. (1996). Another look at the effects of appearance, gender, and job type on performance-based decisions. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 20, 437-445. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.1996.tb00310.x Eagly, A. H. (1987). Sex differences in social behavior: A social-role interpretation. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. Eagly, A. H., & Karau, S. J. (2002). Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychological Review, 109, 573-598. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.109.3.573 Eagly, A. H., & Karau, S. J. (2002). Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychological Review, 109, 573-598. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.109.3.573 Eagly, A. H., Mitchell, A. A., & Paludi, M. A. (2004). Social role the- ory of sex differences and similarities: Implications for the sociopoli- tical attitudes of women and men. Praeger guide to the psychology of gender (pp. 183-206). Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers/Greenwood Publishing Group. Fiorentine, R. (1988). Sex differences in success expectancies and causal attributions: Is this why fewer women become physicians? Social Psychology Quarter l y , 51, 236-249. doi:10.2307/2786922 Fiorentine, R., & Cole, S. (1992). Why fewer women become physi- cians: Explaining the premed persistence gap. Sociological Forum, 7, 469-496. doi:10.1007/BF01117557 Francesco, A. M., & Hakel, M. D. (1981). Gender and sex as determi- nants of hireability of applicants for gender-typed jobs. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 5, 747-757. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.1981.tb01098.x Galinsky, A. D., & Moskowitz, G. B. (2000). Perspective-taking: De- creasing stereotype expression, stereotype accessibility, and in-group favoritism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78, 708- 724. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.78.4.708 Glick, P., Larsen, S., Johnson, C., & Bransititer, H. (2005). Evaluations of sexy women in low- and high-status jobs. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 29, 389-395. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2005.00238.x Heilman, M. E., & Haynes, M. C. (2005). No credit where credit is due: Attributional rationalization of women’s success in male-female Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 85  C. A. ISAAC ET AL. 86 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. teams. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 905-916. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.90.5.905 Heilman, M. E., & Okimoto, T. G. (2007). Why are women penalized for success at male tasks?: The implied communality deficit. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 81-92. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.92.1.81 Heilman, M. E., Wallen, A. S., Fuchs, D., & Tamkins, M. M. (2004). Penalties for success: Reactions to women who succeed at male gen- der-typed tasks. Journal of A pp lied Psychology, 89, 416-427. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.89.3.416 Hill, C., Corbett, C., & St. Rose, A. (2010). Why so few?: Women in science, technology, engineering and mathematics. Washington DC: American Association of University Women. Holt, C. L., & Ellis, J. B. (1998). Assessing the current validity of the Bem Sex-Role Inventory . Sex Roles, 39, 929-941. doi:10.1023/A:1018836923919 Hyde, J. S. (2005). The gender similarities hypothesis. American Psy- chologist, 60, 581-592. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.60.6.581 Isaac, C. (2007). Women deans: Patterns of power. Lanham: University Press of America. Isaac, C., Lee, B., & Carnes, M. (2009). Interventions that affect gender bias in hiring: A systematic review. Academic Medicine, 84, 1440- 1446. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181b6ba00 Jacobs, J. A., & Gerson, K. (2004). The time divide: Work, family, and gender inequality. Cam bridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Kristeva, J. (1995). New maladies of the soul/uniform title: Nouvelles maladies de l’ame. English. New York: Columbia University Press. Loden, M. (1996). Imp l em e nt i n g d i ve r si t y. Chicago: Irwin Pro fe s s i on a l . Major, B., & Konar, E. (1984). An investigation of sex differences in pay expectations and their possible causes. The Academy of Man- agement Journal, 27, 777-792. doi:10.2307/255878 Major, B., Shaver, P., & Hendrick, C. (1987). Gender, justice, and the psychology of entitlement. Sex and gender (pp. 124-148). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc. Mason, M. A., & Goulden, M. (2004). Marriage and baby blues: Re-defining gender equity. Annals of the American Academy of Po- litical and Social Science, 596, 86-103. doi:10.1177/0002716204268744 Masten, A. S. (2007). Resilience in developing systems: Progress and promise as the fourth wave rises. Development and Psychopathology, 19, 921-930. doi:10.1017/S0954579407000442 McConnell, A. R., & Fazio, R. H. (1996). Women as men and people: Effects of gender-marked language. Personality and Social Psychol- ogy Bulletin, 22, 1004-1013. doi:10.1177/01461672962210003 Morley, L. (2006). Hidden transcripts: The micropolitics of gender in Commonwealth universities. Women’s Studies International Forum, 29, 543-551. doi:10.1016/j.wsif.2006.10.007 National Academy of Sciences National Academy of Engineering In- stitute of Medicine of the National Academies (2006). Beyond biases and barriers: Fulfilling the potential of women in academic science and engineering. Washing ton DC: National Academies Press. O’Brien, L. T., & Crandall, C. S. (2003). Stereotype threat and arousal: Effects on women’s math performance. Personality and Social Psy- chology Bulletin, 29, 782- 789. O’Heron, C. A., & Orlofsky, J. L. (1990). Stereotypic and nonstereo- typic sex role trait and behavior orientations, gender identity, and psychological adjustment. Journal of Personality and Social Psy- chology, 58, 134-143. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.58.1.134 Overton, G. K., McCalister, P., Kelly, D., & Macvicar, R. (2009). Prac- tice-based small group learning: How health professionals view their intention to change and the process of implementing change in prac- tice [Article]. Medical Teacher, 31, E514-E520. doi:10.3109/01421590902842425 Plant, E. A., & Devine, P. G. (2009). The active control of prejudice: Unpacking the intentions guiding control efforts. Journal of Person- ality and Social Psychology, 96, 640-652. doi:10.1037/a0012960 Plant, E. A., Hyde, J. S., Keltner, D., & Devine, P. G. (2000). The gen- der stereotyping of emotions. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 24, 81-92. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2000.tb01024.x Prochaska, J. M., Mauriello, L. M ., Sherman, K. J., Harlow, L., Silver, B., & Trubatch, J. (2006). Assessing readiness for advancing women scientists using the transtheoretical model. Sex Roles, 54, 869-880. doi:10.1007/s11199-006-9053-8 Prochaska, J. M., Prochaska, J. O., & Levesque, D. A. (2001). A Tran- stheoretical approach to changing organizations. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 28, 247-261. doi:10.1023/A:1011155212811 Prochaska, J. O., & Velicer, W. F. (1997). The transtheoretical model of health behavior change [Article]. American Journal of Health Promotion, 12, 38-48. doi:10.4278/0890-1171-12.1.38 Ridgeway, C. L. (2001). Gender, status, and leadership. Journal of Social Issues, 57, 637-655. doi:10.1111/0022-4537.00233 Rudman, L. A. (1998). Self-promotion as a risk factor for women: The costs and benefits of counterstereotypical impression management. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 629- 645. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.74.3.629 Rudman, L. A., & Glick, P. (1999). Feminized management and back- lash toward agentic women: The hidden costs to women of a kinder, gentler image of middle managers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77, 1004-101 0. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.77.5.1004 Rudman, L. A., & Glick, P. (2001). Prescriptive gender stereotypes and backlash toward agentic women. Journal of Social Issues, 57, 743- 762. doi:10.1111/0022-4537.00239 Schwandt, T. A. (2001). Dictionary of qualitative inquiry (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Snyder, R. C. (2008). What is third-wave feminism? A new directions essay. Signs: J ou r na l o f Women in Culture & Society, 34, 175-196. Spencer, S. J., Steele, C. M., Qu inn , D. M., Hun ter, A. E., & Ford en, C. (2002). Stereotype threat and women’s math performance. Readings in the psychology of gender: Exploring our differences and common- alities (pp. 54-68). Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon. Steele, C. M. (1997). A threat in the air: How stereotypes shape intel- lectual identity and performance. The American Psychologist, 52, 613-629. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.52.6.613 Swim, J. K., & Sanna, L. J. (1996). He’s skilled, she’s lucky: A meta- analysis of observers’ attributions for women’s and men’s successes and failures. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22, 507- 519. doi:10.1177/0146167296225008 Valian, V. (1998). Why so slow? The advancement of women. Cam- bridge, MA: The MIT Press. van Anders, S. M. (2004). Why the academic pipeline leaks: Fewer men than women perceive barriers to becoming professors. Sex Roles, 51, 511-521. doi:10.1007/s11199-004-5461-9 Vescio, T. K., Sechrist, G. B., & Paolucci, M. P. (2003). Perspective taking and prejudice reduction: The mediational role of empathy arousal and situational attributions [Article]. European Journal of Social Psychology, 33, 455-472. doi:10.1002/ejsp.163

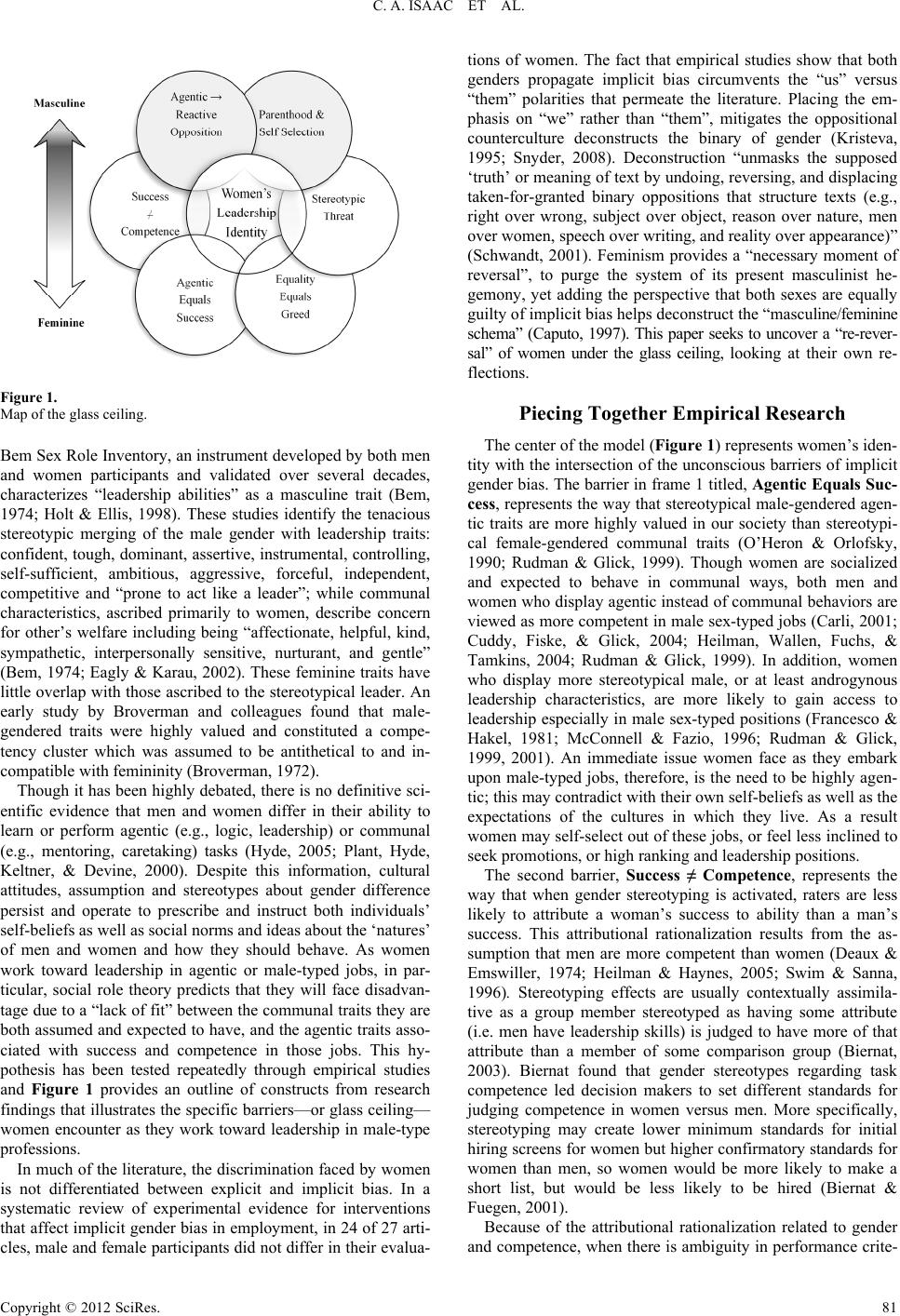

|