Sociology Mind 2012. Vol.2, No.1, 41-49 Published Online January 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/sm) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/sm.2012.21005 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 41 41 Caregiver Identity as a Useful Concept for Understanding the Linkage between Formal and Informal Care Systems: A Case Study Normand Carpentier Centre de Recherche, CSSS de Bordeaux-Cartierville-Saint-Laurent, Montréal, Canada Email: normand.carpentier@umontreal.ca Received April 30th, 2011; revised October 16th, 2011; accepted November 1 7th, 2011 Health systems of most Western countries are already severely strained and pressure will likely mount due to population aging and the anticipated increase in chronic illnesses. Interventions of various forms have emerged in response to the needs of older persons suffering from Alzheimer type dementia, but problems subsist in the linkage between formal and informal care systems. The objective of our study is to achieve a better understanding of the limitations of the partnership between the professional and family systems, employing the identity concept as formulated by Harrison White (2008). We used a case history approach and three analysis techniques to accurately outline the complex nature of the notion of identity: social networks, social representation and narrative analysis. We met with a caregiver on three occasions during a trajectory that spanned a seven-year period. The identity concept provides us with possible ex- planations of families’ attitudes to services. Our findings reveal that the caregiver is partially positioned within the management paradigm defined by the medical model, and strives above all to maintain the continuity of her life in accordance with her identity. Identities seek both social footing and internal co- herence that can be obtained by stories. Many challenges remain in terms of incorporating the medical and psychosocial models within an expanded care model for individuals suffering from dementia and their families. Keywords: Identity; Networks; Linkage Processes; Formal and Informal Systems of Care; Alzheimer’s Disease Introduction The phenomenon of population aging is characterized by a striking increase in chronic illnesses and the concomitant need for long-term care. Numerous observers believe that critical care is still dominant in the culture of current health systems, although chronic diseases are demanding a restructuring of management modes, regulatory mechanisms and funding (Kum- pers, Mur, Maarse, & Raak, 2005; Miller, Booth, & Mor, 2008; Taylor & Bury, 2007). Over the past three decades Alzheimer type dementia has gradually emerged as a fundamental health and social concern. Over 35.5 million people around the world suffer this illness and prevalence doubles every 20 years (Alz- heimer’s Disease International, 2009). Although there is a growing consensus concerning the need to improve the quality of care provided to people with dementia and better serve care- givers and families, many questions remain about the direction to take in setting up adapted intervention programs. Dementia in all its forms represents the opportunity for an al- liance between medicine and the human and social sciences to construct a comprehensive response to the needs of patients and their families. There are multiple reasons for promoting a mixed, bio-psychosocial approach. In the current state of knowledge, intervention is more care-oriented than curative. In the wake of deinstitutionalization, care is generally provided in the home environment, necessarily involving the participation of a large number of individuals. Illness develops differently for each person, depending on their life experiences, abilities, be- liefs and values and physical condition (Parker, 2001). Demen- tia affects all aspects of a person’s life and, in an elderly person, is often accompanied by other health problems. A family member, known as a caregiver, is usually involved at each stage of the care trajectory: they must coordinate, make decisions, and ne- gotiate with the other actors; they are key to ensuring the con- tinuity of care (Carpentier, Bernard, Grenier, & Guberman, 2010). However, the problem of establishing a linkage between formal and informal care systems remains, and it appears to be difficult to identify the reasons for this (Brodaty, Thomson, Thompson, & Fine, 2005; Lyons & Zarit, 1999; Nolan, Lundh, Grant, & Keady, 2003). It is our view that the identity concept will provide us with a better understanding of the problem of establishing partnerships between the actors in the two systems. The objective of our study is to analyze the trajectory of one caregiver and identify elements that will help to explain the difficulty of forming a linkage between the formal and informal care systems. Our analysis is rooted in the identity concept (White, 2008). The case history approach makes it possible to conduct an in-depth analysis of a situation that has attracted little attention by researchers. Linkage between the Care Systems In order to understand the principles enabling the formation  N. CARPENTIER of a linkage between two care systems it is important first to identify several essential components of these systems. In its simplest form, the linkage process consists of a connection between social actors belonging to different systems. In Figure 1, a professional practitioner is matched with a family caregiver: these two actors belong to broader relationship networks of specific configurations and ideologies. The practitioner func- tions according to an approach inspired by biomedical, psy- chological and social models, or a combination of all three (Bond, 2001). The treatment commonly provided to the public today is still inspired by the biomedical model, and comprises a management process consisting of patients being involved in prevention activities and encouraged to participate in early screening procedures, the establishment of a diagnosis, and the application of a treatment protocol. This form of man- agement was developed to deal with acute diseases, where illness is conceptualized in rational terms, often decontextu- alized, and the physician is seen as the principle repository of knowledge (Pesco-solido, 1994). The use of psychological and social models to address the specific characteristics of dementia is increasingly prevalent in intervention practices. A growing literature has focussed on concepts like personhood, person-centred care and public space and home environment (Kitwood, 1997; Brittain, Corner, Robinson, & Bond, 2010). Psychosocial approaches are still in the embryonic stage in intervention programs, but are increasingly considered essen- tial to the delivery of quality care (Edvardsson, Winblad, & Sandman, 2008). The practitioner also functions inside an organization. For the past 15 years, shortcomings in the management of geriatric care have led decision-makers toward managerial models, de- signed to increase efficiency and coordination between re- sources and professionals, thereby improving management and allowing for smoother continuity of care (Kodner, 2002). These forms of management are not, however, problem free (see Gross, Temkin-Greener, Kunitz, & Mukamel, 2004). Last, the formal care system represents a cultural authority that is vested with considerable power in our societies (Starr, 1982). Here, we introduce the notion of identity, which will be dis- cussed further in the next section. Front-line practitioners are individual identities that adhere, to a greater or lesser degree, to mana gerial car e mode ls or app roache s (F inn, Learmo nth, & Reedy, 2010). Based on observation, it would seem that insti- tutions are no longer able to foster the values that would in- spire their members to ensure that the systems operate har- moniously; rather, we are witnessing interprofessional con- flict and lack of motivation among personnel who are con- fronted with incre. This might rightly be described as friction among individual, organizational and collective identities. Informal care systems are also identities, both individual and collective. Families have become more diverse and complex in recent decades and it seems to be increasingly difficult to identify the resources to which they have access (and are willing to use), the nature of responsibilities they can accept without compromising the health of their members, and their trust in government agencies (Price, Price, & McKenry, 2010). The informal system is com- posed of family members, friends, co-workers and neighbours and usually takes the form of mutual aid or serial-type reciproc- ity (Godbout, 2000; Moddy, 2008). In Figure 1, the caregiver is part of the close support network that is in turn part of the broader family institution. Tensions between the different iden- tities are increasing in societies tending toward individuation. The nature of relations between front-line practitioners and family caregivers has not been the subject of much research and the identity concept might be useful in obtaining a better under- standing of the linkage process between care systems. The Identity Concept The identity concept attracted attention in the human sci- ences during the 1950s with the work of Erik Erikson (1959). A very extensive literature then emerged, both theoretical (Stryker & Burke, 2000) and empirical, particularly with respect to health (Sulik, 2009), caregivers (Hayes, Boylstein, & Zimmer- man, 2009) and dementia patients (MacRae, 2010). Many defi- nitions have been proposed, but two dimensions are usually associated with social identity. The first is the self identity: actors negotiate with themselves and embark on a reflexive process aimed at establishing coherence in terms of their own narrative. The second dimension is the identity for others that is supported by others’ perception of oneself. Network theoreti- cians, notably Harrison White (2008), attributed a specific meaning to the notion of identity: “any source of action, any entity to which observers can attribute meaning not explicable from biophysical regularities” (White, 2008: p. 2). An identity is either individual or collective and is constituted as an entity capable of being recognized and acting in its own name. White (2008) describes four senses of identity. First, identi- ties seek control—not power as such—but control, in order to obtain social footing that will provide relational stability in a threatening, even hostile environment. In the course of encounters and events the identity is trans- formed and engages with other similarly oriented actors. The engagement with a new identity can conflict with other en- gagements (existing relationships) that are difficult to shed and that can be threatening to the actor’s identity. Second, identity is the image actors project to others, in other Figure 1. The two systems of care and the identity concept. 4 2 Copyright © 2012 SciRes.  N. CARPENTIER words, the face adopted in order to be recognized. Actors take their place in the group through a process of comparison: this one is like that, the other one is different, and I too, have my place. Actors adopt codified modes of conduct as they evolve in projects for which they have goals, preferences and competen- cies. In this respect, caregivers adopt a role based on their ex- periences and their conception of a person who helps a de- pendant relative. They are recognized by other identities, which reinforce or trap them in their role. In the third sense, identity is constructed in the tension between the first two identities. It is formed and transformed in a constant back and forth exchange with other identities and networks representing different per- spectives. This third sense involves the definitive formation of the social bond or the failure of this bond. The actor consults, seeks alternatives, opts for conformity or creativity, settles into habitual ways of doing things or innovates extensively. The identity emerges from the frictions characterizing our relation- ships with others. The fourth sense of identity corresponds to an ex post account, after the fact: the autobiographical process is an identity. Identity is rooted in action—in the description of such action—and it takes form in accomplishments and en- gagements. In the autobiographical process, actors describe regular interactions with others and the possibilities of partici- pation in events in the outside world as they construct a “story” about themselves or their identity (Giddens, 1991). The Research Question Identities seek both social footing and internal coherence that can be obtained by the narratives that enable them to address life’s challenges. In this respect, the linkage process between two systems can be viewed as the harmonization of the identi- ties of actors in the systems, while recognizing that these actors are in tension with the other identities of their respective net- works. Linkage corresponds to the process enabling identities to stabilize themselves for a period of time within a network of relationships. In our study, we examined the caregiver’s iden- tity based on a research question: what elements of explanation can the identity concept provide in the context of problematic linkages between the formal and informal care systems for Alzheimer type dementia? It is our view that services cannot be adapted in the absence of a deeper understanding of the identi- ties involved in the provision of care. Method The case study approach enables researchers to conduct an in-depth examination of a social phenomenon for which there exists little information as yet and to propose an explanation for this phenomenon (Ragin & Becker, 1992).We used three tech- niques to outline the identities’ subjective and objective dimen- sions over the course of a trajectory. The Case The caregiver is a woman in her sixties who lives with her husband; the couple had three children who are now living in different cities across the continent. We interviewed the care- giver on three occasions during a trajectory that spanned nearly seven years. The caregiver’s mother developed dementia after living on her own since her husband’s death. The family, of Jewish heritage, emigrated from Eastern Europe after the Sec- ond World War. A total of 15 services were used during the care trajectory, including four residential centres. Gathering the Data The caregiver’s social support network was obtained during each interview. We used a “name generator” which is a set of questions in which the respondent identified the alters that pro- vided her with emotional, instrumental, social or informational support. The support network that was present at the trajec- tory’s start (T0) was obtained during the first interview. The presence or absence of relationships among alters was also obtained. In the second stage, the caregiver was invited to re- count the story of her mother’s illness and describe anything that would help to provide a complete understanding of the situation. A semi-directive questionnaire was used to guide the interview and, more specifically, to document service use. Close attention was paid to processes following or preceding pivotal moments: who was involved in the events? Who offered sug- gestions or advice? What was the impact of the decisions and perceived perceptions? The caregiver was also asked to situate the “start of the illness” and the “entry into the caregiver ca- reer”, in other words, the moment in which she took on new tasks in response to manifestations of dementia. Data Analysis Through repeated measurements of the caregiver’s support network we were able to observe variations in relational struc- tures and identify actors who would potentially support the identities. These alters form a support network that facilitates the communication of opinions and propagation of attitudes. We processed the verbal content of the interviews by employ- ing two qualitative approaches. First, the subjective aspects of the identities were analyzed using a structural approach known as social representations (Carpentier, Ducharme, Kergoat, & Bergman, 2008). This approach consists of identifying prede- fined or emerging concepts in the respondent’s discourse and then grouping them according to the frequency of their occur- rence. The “core sy stem” forms the basis of representations and gives direction to numerous social practices while defining the basic elements of the identity. In the “first zone” we find ele- ments that come into play during the transformation of identi- ties, including contradictions or ambivalent feelings underlying the identities. Less frequently manifested concepts (second zone) can help personalize life stories and serve as the subject of content analysis. This analysis provides information on the respondent’s perception of how they are seen by others, their reference points, the search for relationships of trust, the di- mension of chance, etc.—in other words, elements to guide us in better understanding the identity. The second approach em- ployed was narrative analysis. Narrative discourse organizes life, social relations and aids the understanding of the reflexive processes with which people interpret the past and present and plan for the future (Daiute & Lightfoot, 2004). We used a tech- nique whereby we situated all the actors involved in the trajec- tory and analyzed decision-making, events, actions and nego- tiations as they occurred over time (Carpentier & Ducharme, 2005). In this way, we were able to identify the actors who could have facilitated or impeded linkages between the systems. Narrative analysis allowed us to break down the trajectory into sequences, based on pivotal actions, or points of disturbance Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 43  N. CARPENTIER that trigger action, force actors to assume their positions and significantly modify the trajectory’s course. Case Study Figure 2 shows the evolution of the caregiver’s support net- work and the resources she turned to for help during the seven years of the trajectory. The caregiver named nine support fig- ures during this period, with an initial network composed of seven actors (T0) and a final network of three actors (T3). The mother (who would develop dementia) used 15 aid resources, the one of longest duration being the family physician (No. 1) and the one of shortest duration, a day centre that she attended for one day (No. 9). The narrative analysis revealed five action sequences. Table 1 illustrates social representations and lists the concepts most frequently observed in the caregiver’s discourse (“second zone” concepts are partially described). Table 2 presents the actors involved in the sequences and briefly describes certain elements that could guide the search for explanations of linkage prob- lems. Nineteen actors were particularly active in the sequences, eleven of whom were from outside the family. Caregiver’s Initial Identity The caregiver raised her three children in the same building as her parents’ home. Most of her experiences and transitions took place within the family setting, which is still reflected today by the large number of family actors in her initial support network (Figure 2, Network-T0). The caregiver believed she had a special relationship with her mother and referred fre- quently to their shared past: “I’m her history” (Table 1-T1, Social History, Attachments). The family sphere remained cen- tral, even if its members are widely dispersed geographically and their relations are fairly conflictual (Table 1-T1, Core Sys- tem). The caregiver’s identity at the moment of entry into the trajectory was clearly rooted in a culture of support that is pri- marily centred on family responsibility. First Sequence: Entry into the Trajectory The caregiver described the start of the illness trajectory as being a medical appointment during which her mother informed the family physician about feelings of anxiety, a diminished ability to function and memory loss. She also expressed the desire to live in a seniors residence. The doctor prescribed an- tidepressants and supported the mother’s plan to find an adapted residence. Apparently unaware of early dementia s- creening, the physician did not consider referring the mother to a memory clinic. Furthermore, the family did not consider the possibility of prevention measures for memory loss and associ- Figure 2. Transformation of social suppor t and use of services during the 7-year trajectory. 4 4 Copyright © 2012 SciRes.  N. CARPENTIER Table 1. Caregiver’s social representations at three moments during the care trajectory (partial list of concepts). T1 T2 T3 Description n% Description n %Description n% Core system Coping 1614.1% Di s satisfied w it h services 13 8.9%Grief 911.84% Tensions with informal network(IN) 7 6.1% Physical problems 10 6.9%Dignity 79.21% First zone Psychological problem 76.1% Coping 9 6.2%Physical problem 67.89% Social history 65.3% Confronting a pa inful situation 8 5.5%Tension s within IN 56.58% Control 65.3% Caregiver open to service s 8 5.5%Religion 45.26% Empathy 55.3% Cost 8 5.5%Reconnaissance 45.26% Family responsibilities 43.5% Other family problem 8 5.5%Attac hment 33.95% Attachment 43.5% Respect 6 4.1%Social & personal distance 33.95% Physical problems 43.5% Geographical distance 6 4.1%Geographic distance 33.95% Other family problems 43.5% Positive experience with professionals6 4.1%Social hist ory 22.63% Alters’ current/past experie nces 32.6% Empathy 4 2.7%Positive experience of services 22.63% Second zone Withdrawal 32.6% Lack of resources 4 2.7%Confronting a painful situation 22.63% Normalization 32.6% Lack of sensibility 4 2.7%Empathy 22.63% Recognition 32.6% Psychological problems 4 2.7%Dissatisfied 22.63% Uncertainty 21.7% Social history 3 2.0%Lac k of sensitivity 22.63% Anxiety 21.7% Family responsibilities 3 2.0%Positive experience with professionals22.63% (…) (…) (…) ated the mother’s reactions with the normal aging process. Five actors were especially important during this sequence (Table 2) and they worked together to find a residence for the mother. Conflicts arose, however, when the caregiver thought her sister had not sufficiently consulted her about the choice of a resi- dence. The two sisters stopped see each other and the mother went to live in a residence chos en by the caregiver . Second Sequence: Family Positioning The second sequence, which lasted nearly two years, was ini- tiated by the mother’s entry into a residence (pivotal point) and involved eight actors (Table 2). This was a relatively stable period, from a clinical point of view, and the family positioned itself during this time. First, none of the family expressed their intention to invite their mother to live with them; they respected her wish to live in a residence, especially since she was finan- cially indepen dent. Third Sequence: Active Phases The third sequence began when the mother was hospitalized; 13 actors in particular were present during this sequence (Table 2). First, in conjunction with the family physician, steps were taken to get the mother an appointment at the cognition clinic. The geriatrician diagnosed possible dementia, prescribed an experimental drug, handed out a pamphlet on available re- sources and proposed a follow-up appointment in six months. Some family members, especially the caregiver, continued to downplay the memory problems and worried more about their mother’s other health problems. During this period, the family sought a new residence and obtained the aid of a social worker to help transfer the mother to another institution. Wanting the best for her mother, the caregiver chose a semi-private resi- dence that provided a high level of care. Furthermore, several efforts were made to obtain services. The daughter and son-in- law work in the health field and were able to provide a lot of advice in this area. The caregiver acknowledged these two ac- tors as providing support only in terms of medical advice (Fig- ure 2: T1-T2). The mother obtained a place in a day centre but she only went once, finding it of little interest. The family then hired a private companion who met with their mother once a week at the residence. During the interview, the caregiver in- sisted on discussing a family conflict: “You have to put this in, I’ll tell you why, because it shows how life can be disrupted by the children of the caregiver, which makes it even harder”. The caregiver described an incident involving misunder- standings and accusations that had caused great upheaval among family members who were accusing each other mutually of craziness and telling each other to see a psychiatrist. Resolu- tion of this problem was facilitated by an intervention by the family physician, who referred them to family counselling. The physician, who cares for nearly all the family members, is viewed as supportive by the caregiver (Figure 2: T1-T3). Near the end of this sequence, the caregiver was faced with a big decision. She realized that she had moved her mother into a specialized residence too soon and it had been both relatively expensive and inadequately adapted to handle her mother’s dementia. The mother was finally moved into a family-type resource (private residence with a number of residents) and a social worker helped the caregiver with the transfer. Fourth Sequence: Another Major Health Problem The fourth sequence was triggered by the mother’s hospi Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 45  N. CARPENTIER Table 2. The 19 social actors involved in the five action sequences. Sequence Actors Type of relations and facilitator/hinder to linkage process 1. Caregiver Feels close to the mother. Us es a strategy of consultation a nd control 2. Mother Thinks she has dementia; actively planning for the future 3. Family doctor Has known the family fo r s everal years (mother, caregiver, husband) 4. Brother Cl ose bond but lives out of t own 1. 8 months 5. Sister Broken ties due to fights over decision -making 1. Caregiver Progressively engaged; needs control over the s i tu ation 2. Mother Still autonomous, and seeks s ervices b y herself 3. Family doctor Used by the mother to ge t s ervices 4. Brother Cl ose bond, gi ves emotional support 5. Sister Acts on her own, which is not well perceived by the caregiver 6. Home care w o r ker No contact with family. Bathes mother o n ly 7. Daughter Weak b on d , seen only as support for medica l advice 2. 22 months 8. Brother - i n-law Weak bond, see n o nly as support for medical advic e 1. Caregiver As illness progresses, soc i al pressure increases 2. Mother Health deteriorates 3. Family doc t or Used for various tasks: adv i ce, emotional support, inst i tutional transfer 4. Brother Ceases offe r ing support due to his own family problems 5. Sister Contact only c auses frustration 7. Daughter Gives advice but relationship is ambiguous 8. Brother -i n-law Bond remains weak 9. Geriatr ician Provides diagnosis and prescription for d r ugs; suggests follow-up every six months 10. Social worker Used briefly for evaluation and referral to services 11. Private caregiver Sees the mother at residence; no contact with family 12. Social worker Used briefly for evaluation 13. Social worker Used briefly for evaluation and referral to private seniors residence (family-type) 3. 23 months 14. Family-type residence The caregiver expects a family-type atmosphere at this resource 1. Caregiver Lack of support, s pecially f ro m family members 2. Mother Participates less and less in decision-ma king 3. Family doctor Again, very useful and w ell appreci ated 13. Social worker Briefly used for residential transfer 14. Family-type res i d ence Tremendous disappointment for t h e caregiver, no family atmosph ere; no respect for the mother 4. 12 months 15. Nurse Used for medical care; no contact with family 1. Caregiver Is exhausted; takes four mo nths off to rest 2. Mother Live s no w in residence w i th hi gh level of care 16. Reside nce staff Caregive r r eports no personal cont act with a ny staff members 17. Husband Gives support at this difficult time 18. Family Caregive r i s d i sappointed in them 5. 16 months 19. Friend s and visitors Feels estranged from these indi vi duals talization and the discovery that she had cancer. The caregiver was against any form of treatment because she believed that chemotherapy would weaken her mother too much, physically and psychologically. She wanted her mother to be able to pre- serve her dignity in the last stages of her life. The family phy si- cian was again solicited to refer a nurse to come and provide home care. Six actors were present during this sequence and the caregiver’s support network diminished progressively (Figure 2: T2). The caregiver struggled to obtain support and under- standing; her sense of dissatisfaction led her to isolate herself; moreover, this was a difficult time for the family, with several of its members falling ill (Table 1-T2: Core System). The care- giver was constantly confronted with diverging opinions and some family members began to introduce religious considera- tions, creating additional stress. Moreover, tension and the sense of being misunderstood un- dermined the caregiver’s relations with members of the seniors residence (Table 1-T2, Core System). The caregiver expected to find a family setting in which she could come and see her mother at any time without prior notice, while benefiting from the staff’s support. She was disappointed and she had several complaints: locked closet, the wearing of other people’s clothes, use of a telephone answering machine, etc. Observing her mo- ther’s deteriorating health (Table 1-T2: Painful Situation), the 4 6 Copyright © 2012 SciRes.  N. CARPENTIER dimension of respect and dignity took on key importance: “I want my mother to have respect. The ultimate thing is to lose is respect, you can lose furniture and possession and money, what- ever, but your respect … it doesn’t cost anybody anything to be polite, to be honest. She’s not getting respect there”. Once again, steps were taken to move the mother into another residence. A social worker and the family physician were called to return the mother to the earlier residence, the one providing a higher level of care. T he transfer was acco mplished in a climate of conflict and dissatisfaction on the part of the caregiver. The social representations analysis also indicates larger and demanding family concerns (Tab le 1-T2: Other Family Problems). Fifth Sequence: Palliative Care This last sequence, which lasted 16 months and involved six actors, began with the mother’s move into a new residence. he caregiver witnessed the deteriorating health of her mother, who was suffering not only from dementia but also from a nemia and cancer. This had a huge impact on the caregiver. cumulated fatigue resulted in the caregiver’s hospitalization and the physi- cian prescribed four months of complete rest. When her mother died, the caregiver once again became actively involved, how- ever, but the ceremonies affected her deeply. She found the behaviour of family members and friends who had not been there for her in the last few years inappropriate. When we in- terviewed her, the caregiver was in mourning and referred often to the dignity of her mother, which had not always been re- spected (Table 1-T3: Grief, Dignity). She felt misunderstood, resentful and bitter. She said she felt she had been treated un- fairly and, especially, felt rejected by many members of her family. The support network was at its lowest point in the seven years. Her spouse remained present during all her years in her support network (Figure 2). Discussion The objective of our study was to identify elements that would help to explain the difficulty of forming a linkage be- tween the formal and informal care systems. Our analysis was rooted in the concept of identities, revealing the importance of social support when it comes to dealing with uncertainty and also, the caregiver’s need to maintain internal coherence by means of a narrative. In this case study we observed a constant shrinking of the caregiver’s support network, the lack of new sources of support from the informal resources, and subjective elements that signalled the difficulty of the challenge. These observations may seem disturbing, particularly if we consider that this was not a context of healing—and the caregiver agrees with this qualification—but rather one of accompaniment and support in which the priority should be the creation of relations to enhance the quality of a person’s day to day life. We propose four elements to explain the linkage problems. The first could be tied to a phenomenon associated with the exchange phenomenon. Family relations are based on a specific system of exchange, le don, or gift (Mauss, 1954); it is a system that is perpetually imbalanced, irregular and unpredictable. Family ties are nourished by this type of exchange which is the only viable exchange in day-to-day life or in a crisis period. This form of exchange is absent or difficult to reproduce in the formal care system. The relationship between the family physi- cian and the caregiver was maintained, however, over a long period. The physician knows the family history; he sees many of its members individually and provides technical and emo- tional support. This type of relationship and exchange was not duplicated with the new services connected with the mother’s dementia. Many of the meetings with practitioners consisted solely of assessments for the purpose of obtaining access to resources. As observed by Adams & Gardiner (2005), a psy- chosocial orientation could, however, facilitate communications between family and practitioners, enabling practitioners to play a more active and sensitive role in the caring process. A second explanation for linkage problems could reside in the fourth sense of identity, defining how the caregiver views herself and how others view her role. The caregiver plainly saw herself as the central person in her mother’s life and she in- tended to maintain this relationship, which was an integral component of her identity. It was a relationship she was reluc- tant to share, as seen by the conflicts with her sister at the start of the trajectory, and later with the practitioners in the fam- ily-type residence. Her commitment to her mother was in con- tinuity with her personal experience, characterized by little reliance on resources outside the family, at least until recently. This could partly explain the failure to adjust to the staff of the family residence whose approach she found differed too much from her way of doing things. Last, the centrepiece of the care- giver’s identity was her need to maintain a sense of continuity in terms of family life (Bury, 1982), which she revealed by minimizing the gravity of her mother’s dement ia. Continuity of care, which is stressed by managerial models, is important, but should not supplant the person’s biographical continuity, which is the basis of their identity and enables them to maintain onto- logical security (Giddens, 1991). Third, the caregiver did not necessarily identify with the strict planning approach, based on rational and planned actions, that is inherent to a medical program. The care she provided for her mother was in line with their daily lives, comprising unex- pected events, religious considerations, latent conflicts and family secrets. The management stages of a medical program were absent or undefined; this system is not part of the family identity and could even inspire guilt feelings when members realized their “negligence” in failing to take preventive action. The trajectory also included backtracking, for example, the coming and going between housing resources offering different levels of care; at times it became completely divorced from a healing scenario, as in the refusal to accept treatment for the mother’s cancer. The mother’s dignity was at the forefront of the caregiver’s concerns. Continuity of care as described by healthcare managers is viable within the conventional frame- work of certain (acute) types of illness. Transitions from one service to another for the purpose of achieving continuity, however, are actions based on more than a purely rational as- sessment derived from a few cursory readings. Every decision must be carefully considered and matched with the identities of caregivers, who have an overall perspective of the patient’s living environment, particularly practical considerations, but also in terms of their relative’s dignity. A final explanation could be linked to the third sense of iden- tity, which involves the negotiations that are necessary to form bonds. Caregivers benefit from support and encouragement, but they are also subject to negative pressure and criticism. They must negotiate continuously, both in response to the progres- sion of their ill relative illness and to life’s ups and downs. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 47  N. CARPENTIER These negotiations carry a price; they are exhausting, and end- ing certain relationships can bring relief, especially when a caregiver believes that knowledge of the patient’s life history is essential to making appropriate decisions. Academic Implications Our study borrowed from Simmel’s thinking in which social life is apprehended through the analysis of reciprocal actions among actors over time. We found the identity concept, as proposed by White (2008), stimulating and helpful to the un- derstanding of the forms of social interaction in play with re- spect to linkages between systems. According to this perspec- tive, actors are no longer simply autonomous, strictly rational entities, they act in keeping with the context in which they find themselves, and their decisions can be understood in terms of their interactions (in other words, their network). In terms of methodology, we decided to combine techniques in order to reveal objective and subjective aspects of the trajectory. In light of the increasing complexity of the informal care systems, we must renew and expand our investigative tools, especi ally since solid research is needed to raise the medical community’s awareness of the importance of human relations in chronic care. Research Orientation for Intervention Practice Our study confirms the importance of supporting efforts to incorporate psychosocial models into care intervention pro- grams for patients with dementia. The analysis of identities reveals the central role of subjectivities, communication and interactions, and also the emotional burden that transcends the trajectories of chronic care. This brings us to the same question as the one posed by Grant, Morales and Sallaz (2009): is there a place for emotions in modern work organizations? This ques- tion is fundamentally important to chronic care and should prompt further analyses of professional identities, which, far from being delimited by rational imperatives, must take into account the constant search for support that will enable actors to deal with their environment, which is often hostile and un- predictable. Linkage is achieved by reducing the tensions among identities, while recognizing that these identities are situated within broader systems. In this respect, Parker (2001) observes that the desire for efficiency inherent to the institu- tional management model inspires concern among practitioners who view performance and control measures as a way of cir- cumventing the ethical and humanist considerations essential to the application of psychosocial models. While taking into ac- count administrative requirements, new approaches must be developed such as mediation services to reconcile unravelling families. More active practices need to be designed to tempo- rarily compensate for disintegrating informal networks, while remaining realistic about the capacity of services to integrate the “gift” exchange system. Efforts must also be pursued to develop family’s educational programs without attempting to change drastically caregivers to make them fit in with the re- quirements of the medical program: identities are not easily transformed. Limitations and Strengths The limitations of a case study approach have been exten- sively documented and our study will naturally raise questions regarding the data’s soundness, representativeness and the ca- pacity for generalization. Such an approach does not allow us to document the diversity of trajectories, which vary according to each family’s particular context, the pace at which the illness progresses, relational status and residential arrangements. The case study approach is still central to sociological analysis, however, it enables us to document complexity, the phenome- nology of a phenomenon and its causal processes (Abell, 2009). This study is rare in that we were able to meet with the care- giver on several occasions over an extended period, and it pro- vides a new angle on a problem that is still mostly analyzed in terms of the obstacles to receiving care (Carpnetier et al., 2008). The problem of linkage is presented here as tensions among the identities and it is our view that services will not have any prac- tical value without taking this dimension into account. Conclusion The linkage between two systems is a complex phenomenon that engages actors in identities that shift from conciliating to oppositional, while undergoing constant transformation. Any efforts to reform the healthcare system in the current context of aging populations must be informed by an understanding of both institutional structures and the functioning of family sys- tems. A deeper understanding of identities is key to improving healthcare management, as this could explain reactions that appear illogical from the perspective of administrators but that, from a caregiver’s standpoint, spring from a concern for iden- tity’s continuity. These actors are essential partners who have the capacity to accelerate or slow the process that enables con- tinuity of care. The challenge resides in the search for a com- mon ground that reflects the concerns and issues raised by the different care models—the management priorities inherent to institutions and the social identities—so that we can develop a care program that will better address the needs of seniors and families. Acknowledgements This research was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (project No. 85031). We would like to extend our sincerest gratitude to the families who took part in this study. REFERENCES Abell, P. (2009). A case for cases: Comparative narratives in soci olo gical explanation. Sociologi cal Meth ods Research, 38, 38-70. doi:10.1177/0049124109339372 Adams, T., & Gardiner, P. (2005). Communication and interaction within dementia care triads. Dementia, 4, 185-205. doi:10.1177/1471301205051092 Alzheimer’s Disease International (2009). World Alzheimer Report 2009. URL (last checked 2 December 2009). http://www.alz.co.uk/research/worldreport/ Bond, J. (2001). Sociological perspectives. In C. Cantley (Ed.), The hand- book of dementia care (pp. 44- 61). Bu ckingham : Open University Press. Brittain, K., Corner, L., Robinson, L., & Bond, J. (2010). Ageing in place and technologies of place: The lived experience of people with dementia in changing social, physical and technological environments. Sociology of Health & Illness, 3 2, 272-287. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9566.2009.01203.x Brodaty, H., Thomson, C., Thompson, C., & Fine, M. (2005). Why caregivers of people with dementia and memory loss don’t use ser v ic es . International Journ a l o f G er i a t r i c Psychiatry, 20, 537-546. 4 8 Copyright © 2012 SciRes.  N. CARPENTIER Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 49 doi:10.1002/gps.1322 Bury, M. (1982). Chronic illness as biographical disruption. Sociology of Health and Illness, 4, 167-182. doi:10.1111/1467-9566.ep11339939 Carpentier, N., & Ducharme, F. (2005). Support network transforma- tions in the first stages of the caregiver’s career. Qualitative Health Research, 15, 289-311. doi:10.1177/1049732304270813 Carpentier, N., Ducharme, F., Kergoat, M.-J., & Bergman, H. (2008). Barriers to care and social representations early in the career of care- givers of persons with Alzheimer’s disease. Research on Aging, 30, 334-357. doi:10.1177/0164027507312113 Carpentier, N., Bernard, P., Grenier, A., & Guberman, N. (2010). Using the life course perspective to study the entry into the illness trajectory: The perspective of caregivers of people with Alzheimer’s disease. Social Science & Medicine, 70, 1501-1508. Daiute, C., & Lightfoot, C. (2004). Narrative analysis: Studying the development of individuals in society. Thous an d O ak s: Sa ge . Dubet, F. (2009). Le trav ail des sociétés. Paris: Éditions du Seuil. Edvardsson, D., Winblad, B., & Sandman, P. O. (2008). Person-centred care of people with severe Alzheimer’s disease: Current status and ways forward. The Lancet Neurology, 7, 362-367. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70063-2 Erikson, E. (1959). Identity and the life cycle. New York: International Universities Press. Finn, R., Learmonth, M., & Reedy, P. (2010) Some unintended effects of teamwork in healthcare. Social Science & Medicine, 70, 1148- 1154. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.12.025 Giddens, A. (1991). Modernity and self-identity. Self and society in the late modern age. Stanford: Stanford University Press. Glendinning, C. (2003). Breaking down barriers: Integrating health- care services for older people in England. Health Policy, 65, 139- 151. doi:10.1016/S0168-8510(02)00205-1 Godbout, J. T. (2000). Le don, la dette et l’identité. Montréal: Découverte. Grant, D., Morales, A., & Sallaz, J. (2009). Pathways to meaning: A new approach to studying emotions at work. American Journal of Sociology, 115, 32 7-364. doi:10.1086/599252 Gross, D. L., Temkin-Greener, H., Kunitz, S., & Mukamel, D. B. (2004). The growing pains of integrated health care for the elderly: Lessons from the expansion of PACE. The Milbank Quarterly, 82, 257-282. doi:10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00310.x Hayes, J., Boylstein, C., & Zimmerman, M. K. (2009). Living and loving with dementia: Negotiating spousal and caregiver identity through narrative. Journal of Aging Studies, 23, 48-59. doi:10.1016/j.jaging.2007.09.002 Kitwood, T. (1997). Dementia reconsidered: The person come first. Buckingham: Open University Press. Kodner, D. L. (2002). The quest for integrated systems of care for frail older persons. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research, 14, 307- 313. Kumpers, S., Mur, I., Maarse, H., & Raak, A. V. (2005). A comparative study of dementia care in England and the Netherlands using neo- institutionalist perspectives. Qualitative Health Research, 15, 1199- 1230. doi:10.1177/1049732305276730 Lyons, K. L., & Zarit, S. H. (1999). Formal and informal support: The great divide. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 14, 183- 196. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1166(199903)14:3<183::AID-GPS969>3.0. CO;2-J MacRae, H. (2010). Managing identity while living with Alzheimer’s disease. Qualitative Health Research, 20, 293-305. doi:10.1177/1049732309354280 Mauss, M. (1954). The gift forms and functions of exchange in archaic societies. Glencoe, IL: Free Press. Miller, E. A., Booth, M., & Mor, V. (2008). Assessing experts’ views of the future of long-term care. Research on Aging, 30, 450-473. doi:10.1177/0164027508316607 Moody, M. (2008). Serial reciprocity: A preliminary statement. Socio- logical Theory, 26, 130-151. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9558.2008.00322.x Nolan, M., Lundh, U., Grant, G., & Keady, J. (2003). Partnerships in family care: Understanding the caregiving career. Maidenhead: Open University Press. Parker, J. (2001). Interrogating person-centred dementia care in social work and social care practice. Journal of Social Work, 1, 329-345. doi:10.1177/146801730100100306 Pescosolido, B. A. (1994). Society and the balance of professional dominance and patient autonomy in medical care. Indiana Law Journal, 69, 1115-1122. Price, S. J., Price, C. A., & McKenry, P. C. (2010). Families & change: Coping with stressful events and transitions (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage. Ragin, C., & Becker, H. (1992). What is a case? Exploring the founda- tions of social inquiry. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Starr, P. (1982). The social transformation of American medicine: The rise of a sovereign profession and the making of a vast industry. New York: Basic Books. Stryker, S., & Burke, P. J. (2000). The past, present, and future of an identity theory. Social Psychology Quarterly, 63 , 284-297. doi:10.2307/2695840 Sulik, G. A. (2009). Managing biomedical uncertainty: The technoscien- tific illness identity. Sociology of Health & Illness, 31, 1059-1076. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9566.2009.01183.x Taylor, D., & Bury, M. (2007). Chronic illness, expert patients and care transition. Sociology of Health & Illness, 29, 27-45. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9566.2007.00516.x White, H. C. (2008). Identity and control: How social formations emerge. Oxford: Princeton.

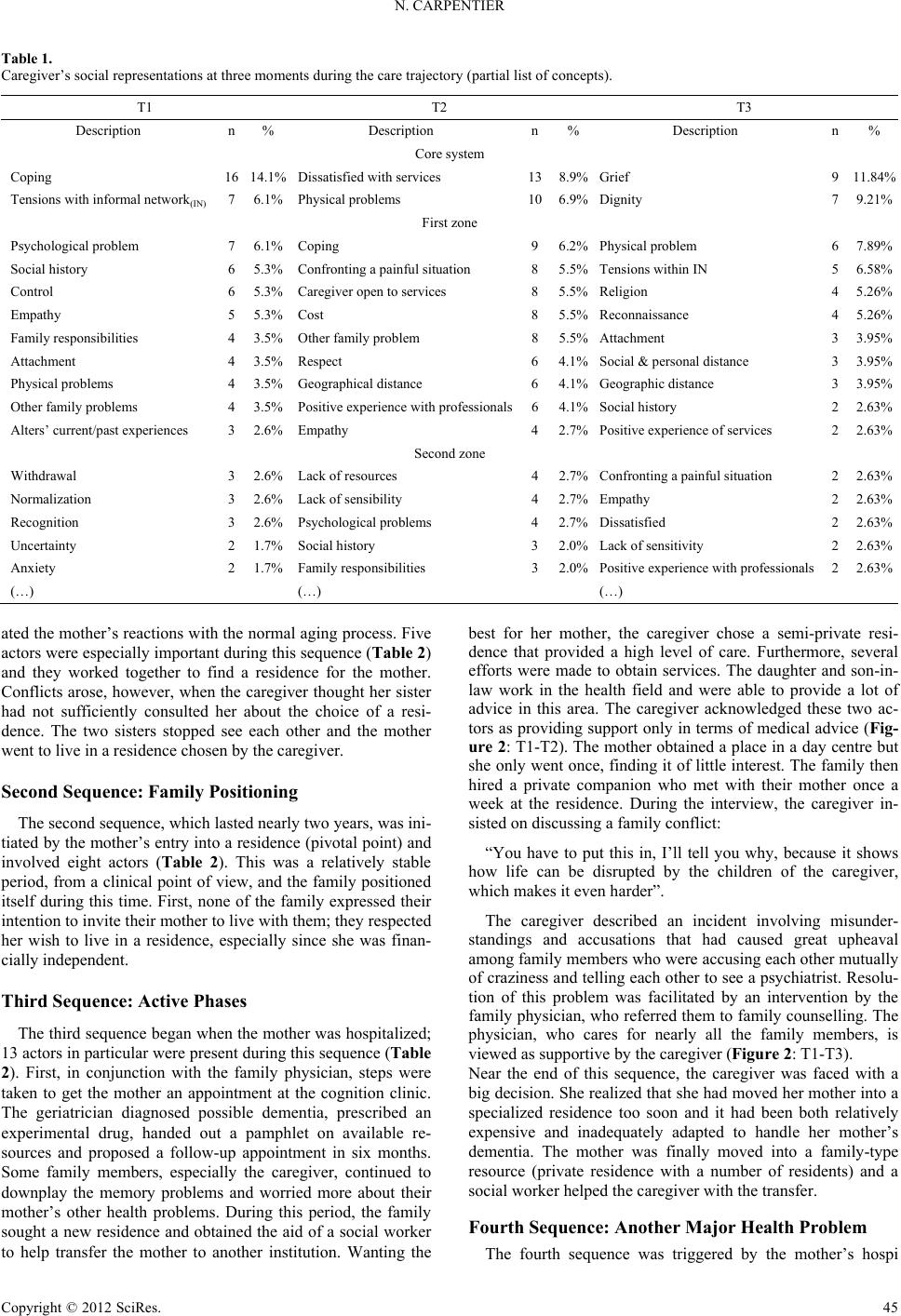

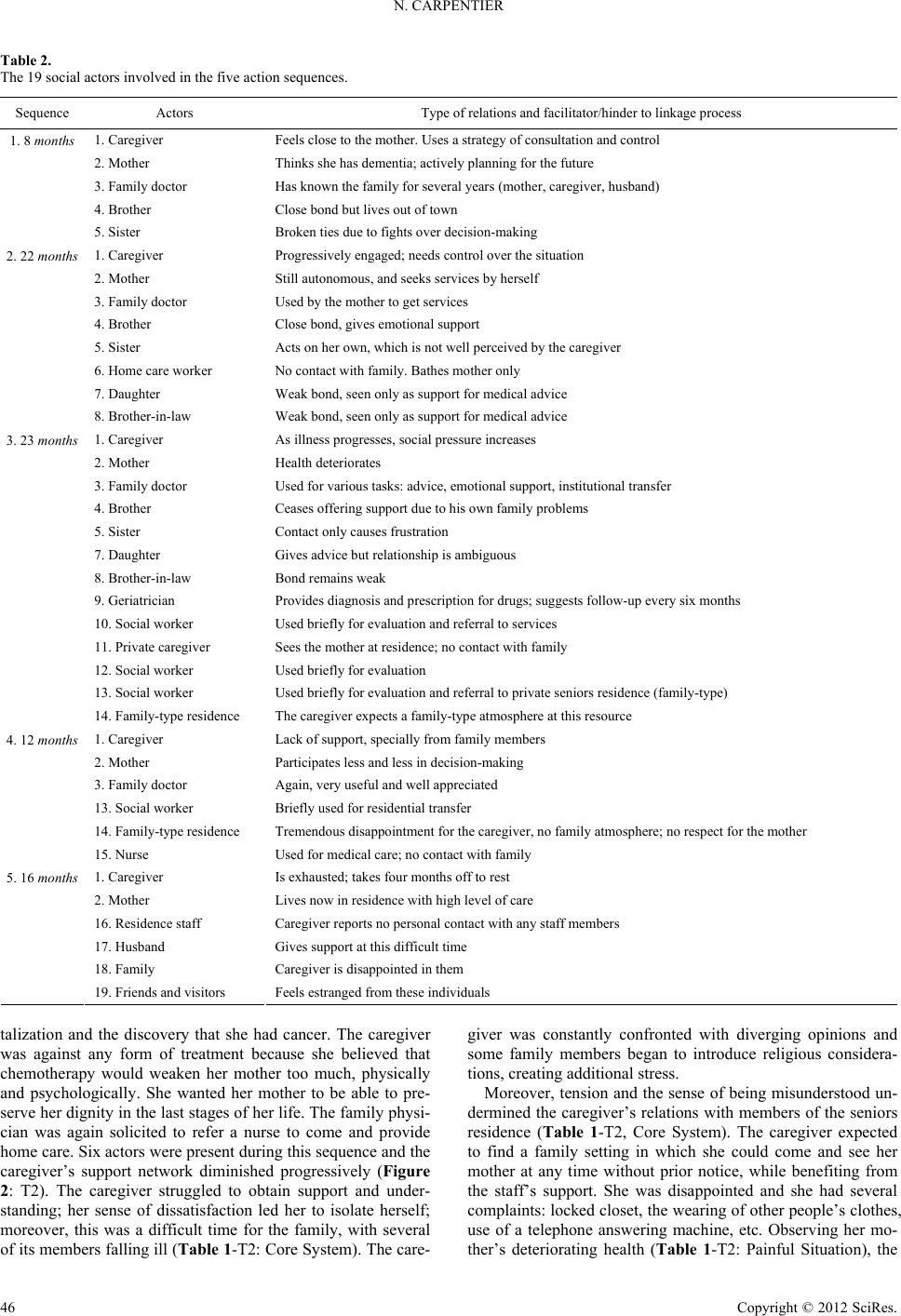

|