Psychology 2012. Vol.3, No.1, 30-35 Published Online January 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/psych) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/psych.2012.31005 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 30 Pre-Schoolers’ Reports of Conflicting Points Secretly Inserted into a Co-Witnessed Event: An Experimental Investigation Using the MORI Technique Kazuo Mori1, Ryuta Takahashi2 1Institute of Engineering, Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology, Tokyo, Japan 2Osaka Family Court, Sakai, Japan Email: kaz-mori@cc.tuat.ac.jp Received November 5th, 2011; revised December 6th, 2011; accepted December 31st, 2011 Thirteen pre-school and ten undergraduate pairs participated as eyewitnesses to a simulated criminal event presented through animated cartoons using a presentation trick (MORI technique). Although there were two different versions, the MORI technique had participants observe only one version without being aware of the other. In three reporting sessions, participants recalled what they presumed they had jointly observed; individually immediately after the presentation, collaboratively after the individual recall, and again individually one week later. The main results were: pre-schoolers, as well as undergraduates, showed better recall in the collaborative tests, though the former generally showed poorer recall than the latter, pre-schoolers tended to conform more frequently than undergraduates in the week-later tests, and both pre-school and undergraduate pairs conformed more often for amendment than distortion. Keywords: Eyewitness Testimony; Pre-School Child Pairs; MORI Technique; Conformity Introduction There are various reasons for the bias of information in wit- ness testimony, but that of co-witnesses has been reported to be crucially influential (Kanematsu, Mori, & Mori, 1996/2003; Gabbert, Memon, & Allan, 2003; for a recent review, see Wright, Memon, Skagerberg, & Gabbert, 2009). In Kanematsu, et al. (1996/2003), co-witness pairs observed the same event, but with hidden discrepancies secretly inserted using a presen- tation trick (the MORI technique, Mori, 2003). Researchers found that, in subsequent discussion of what they had witnessed together, participants tended to modify their own memory of what they had observed in order to conform to that of their co-witnesses. Mori and his collaborators have conducted a se- ries of experiments to investigate the memory distortions of co-witnesses under various conditions: male vs. female pairs (Matsuno, Mori, Hirokawa, & Ukita, 2005), couples vs. unac- quainted pairs (French, Garry, & Mori, 2008), one-vs-two wit- nesses and two-vs-two witnesses (Mori & Mori, 2008), as well as mother-child pairs (Mori & Kitabayashi, 2009). Gabbert, Memon, and Allan (2003) also investigated the co-witness effect on memory recollection utilizing a different paradigm. They showed pairs of participants a simulated criminal event videotaped from two different angles such that each participant viewed one of the two video versions which included some details that were not visible in the other and vice versa. They found a significant proportion (71%) of participants who had discussed the event recalled details that had been ac- quired during the discussion rather than through direct observa- tion. Co-witness conformity research utilizing the Gabbert method (Gabbert, et al., 2003), in which the co-witness pairs observed a slightly different version of an event separately, and that utiliz- ing the MORI technique, in which the co-witness pairs ob- served the same event together without being aware of the du- ality, showed similar research findings. As stated above, fun- damentally both sets of studies revealed that the recollections of independent witnesses tend to be strongly influenced by those of their co-witnesses. Recently, Gabbert, Memon, and Wright (2007) found that participants/witnesses who believed their partners had observed the event longer tended to conform to them. French, Garry, and Mori (2011) found similar results with the Mori method. They manipulated participants’ expectations by leading them to be- lieve that they had either “higher or lower visual acuity” than their partners when together they watched a video event in which several discrepancies had been inserted secretly. The results showed that, although the actual visual acuity was equal in reality, participants who believed that they had “lower visual acuity” conformed more than their counterparts with “higher visual acuity.” It is noteworthy that these two studies independently re- vealed the same fact, that co-witnesses tended to take their partners’ credibility into account when deciding whether they would conform to them or not. The co-witness conformity ef- fects are crucial in the application of research results to actual investigation and judicial practices. Therefore, it is worth em- phasizing that the same research findings need to be corrobo- rated by various independent researchers using different ex- perimental methods. Relatively few experimental studies have been done on co-witness effects in children. Child witness testimony has been a major research topic in applied cognitive and forensic psy- chology. Child witnesses have been studied because they are often the victims in child abuse cases, and the credibility of their memory and overall cognitive ability is a major concern in  K. MORI ET AL. forensic proceedings. Techniques for interviewing young chil- dren and suitable procedures for retrieving reliable reports from them have also been studied rigorously (See a recent review by Davies & Pezdek, 2010). However, the co-witness effect among children has not yet been studied in detail. Roos af Hjelmsäter, Granhag, Strömwall, and Memon (2008) investigated the co-witness effect on children’s memory per- formance using a traditional misinformation paradigm. They interviewed children aged 7 - 13 regarding an event they had experienced two weeks earlier. Prior to the interviews, the chil- dren were exposed to an account of the same event that con- tained some misinformation from a fictional adult co-witness. Although the children’s reports were generally quite accurate, the results showed that the information provided by the adult co-witnesses influenced the children to make errors when they reported about the event. Mori and Kitabayashi (2009) studied the co-witness effect of mother-child pairs using the Kanematsu-Mori-Mori paradigm and found that elementary school children (between 6 to 12 years old) conformed to their co-witness mothers but that their conformity frequency was almost the same as that of the moth- ers to their co-witness children. Out of 92 incidences of con- formity, mothers conformed to their children’s accounts 41 times whereas children conformed to their mothers’ versions 51 times. Candel, Memon, and Al-Harazi (2007) examined the mem- ory conformity of child co-witnesses using the same paradigm as Gabbert, et al. (2003). To our knowledge, it is the only ex- perimental study that has examined the interaction between child co-witnesses. In it, they showed a video to younger (aged 6 - 7) and older (aged 11 - 12) children in pairs, leading them to believe that they had seen the same video as the other child of the pair although they had actually seen different versions. Then the participants were led to discuss what they had viewed together, and finally they completed a recall task individually. Candel, et al. (2007) found that more than 60% of the children “recalled” at least one detail from the video that they had not actually observed themselves. The memory conformity ten- dency was stronger for older than for younger children. All these preceding studies showed basically the same re- sult—that children tend to conform to their co-witnesses. How- ever, the first two studies, Roos af Hjelmsäter, et al. (2008) and Mori and Kitabayashi (2009) used adult-child co-witness pairs. The adult co-witness in Roos af Hjelmsäter, et al. (2008) was a confederate, not a real co-witness. In Candel, et al. (2007), the co-witness pairs were both children, but they watched a video alone, although they were told that they had watched the same video as their partners. Thus, those child co-witnesses might not have had a genuine feeling of having co-witnessed the same event together. As stated above, co-witness conformity research has been conducted in two different experimental modes, one utilizing the Gabbert method, in which co-witnesses separately watched visual stimuli, and one utilizing the MORI technique, in which co-witness pairs watched the same presentation together. The research groups of these two different experimental methods produced similar experimental results, thus corroborating the findings of the authors of the two studies. Therefore, the present study aimed to re-examine the co-witness interactional effect among children, found in Candel, et al. (2007) using the Gab- bert method, by utilizing the MORI technique in a setting in which the participants witnessed the same event simultaneously, sitting side by side. Method Participants Thirteen pre-school pairs (5 - 6 year olds; 12 boys and 14 girls) and ten undergraduate pairs (19 - 20 year olds; six men and 14 women) participated as eyewitnesses in the experiment. Presentation Materials The animated video clips of a simulated criminal event: Two different versions of the Kanematsu et al. movie (1996/ 2003) were converted into an animation by means of frame-by- frame drawings done with Adobe Photoshop software. Each frame was 360 × 360 pixels in size with a resolution of 72 dpi. The corresponding frames of the two video versions were placed side-by-side to produce a combined new frame of 720 pixels wide × 360 pixels high. The animated clip was 50 sec- onds long and consisted of 150 combined frames, presented three frames per second using the mpeg animation software QuickTime Movie on an Apple iBook. In this way, two differ- ent versions of the animation were presented simultaneously on a frame-by-frame basis. The two versions depicted basically the same event—a theft from the bag of a female pedestrian by a man and woman cou- ple driving a car. However, there were three differing points: the color of the criminals’ car, a dark car (Version A) vs a white car (Version B); (b) the clothes of the criminal driver, a parka with lateral stripes (Version A) vs a white shirt (Version B); and (c) the direction the pedestrian walked after the theft, up toward the screen (Version A) vs down away from the screen (Version B). Presentation Apparatuses The experimental apparatuses used for the MORI technique were equivalent to those used in the Kanematsu et al. study, but modified for the child participants, that is, 1) the video clips were animated cartoons rather than regular movies, and 2) sets of circular polarizers were used instead of linear polarizers so that the hidden images would not be seen if the observers tilted their heads. (See, Mori, 2007 for details of the MORI tech- nique.) The experimental setting is depicted in Figure 1. Video projectors: Two DLP video projectors (Yokogawa D-1200X) were used. One each of two types of circular polar- izing filters (R- and L-circular polarizers) was placed in front of the projection lenses of each projector. The projected light, having passed through the polarizer, was polarized circularly with either right- or left-hand rotation. Since the circularly po- larized light can pass through another circular polarizing filter with the same rotational direction while being blocked by a circular polarizer of a different direction, the two images pro- jected onto the same screen can be seen separately by the view- ers, each wearing a pair of suitable polarizing sunglasses. The two projectors were placed side by side approximately 60 cm behind a half-transparent screen to project two different images polarized counter-wise to each other. Half-transparent rear screen: A 20 cm × 20 cm plain ground glass pane 5 mm thick was used as a half-transparent screen. It was mounted on a 180 cm (h) × 90 cm (w) × 0.5 cm (thickness) wooden panel, which contained a 20 cm × 20 cm Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 31  K. MORI ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 32 Figure 1. The experimental setting for presenting two different animated movies on the same screen simultane- ously. The actual animation was presented in full color. window in the middle for the screen. It was the same screen as used in Mori and Kitabayashi (2009). The screen was set about 1 m away from the viewers. Polarizing sunglasses: Two types of circular polarizing sun- glasses suitable for viewing one or the other of the video im- ages were prepared. They looked similar to ordinary sunglasses and were identical to each other. They were made using ordi- nary sunglass frames and cutouts from R- and L-circular polar- izing filter sheets of 0.8 mm thick (MeCan Imaging Inc., Japan). Memory Tests Testing sessions: The witnesses’ recall was assessed three times using “Immediate Tests,” just after the video presentation (individually), “Collaborative Tests,” during discussion (in pairs), and “Week-later Tests,” a week after the discussion (individually). Cued recall test sheets: The assessment of witness memory was done by means of cued recall tests. Female undergraduates pre-trained in conducting child interviews assisted the young participants in taking the tests. The test consisted of 20 ques- tions designed to assess the participants’ memory of the ani- mated event. The question items were selected from both cen- tral and peripheral information in the event. Of those, three questions concerned the three critical items: #3 on the color of the car, #8 on the driver’s clothing, and #20 on the direction the pedestrian walked. The same test sheets were used in all test periods and for all participants. Procedure The experimental procedure was basically a replication of a previous mother-child pair witness experiment (Mori & Kita- bayashi, 2009). Video Presentation Phase In the first phase, the video presentation, Immediate Test, and Collaborative Test were administered to the child partici- pants in a room at their nursery school and to the undergraduate participants in a psychology laboratory. Presentation: Participants entered an experimental room in pairs and sat on chairs placed side-by-side facing the screen ap- proximately 1 m apart. Participants chose a chair at will. Two types of circular polarizing sunglasses, one pair for Version A and another for Version B, were placed on the chairs. As a ruse, the participants were instructed to wear the sunglasses to pro- tect their eyes from glare. Immediate Tests: After watching the animation, the par- ticipants’ recollection of the event was assessed individually by means of cued recall tests. No time limits were set, but it took about five to ten minutes to complete each test. For pre-school participants, female undergraduates majoring in educational psychology assisted the youngsters in taking the test. The assistants were trained beforehand how to handle young children and how to elicit their responses without bi- asing them. Collaborative Tests: After completion of the Immediate Tests, participants were asked to report collaboratively on what they had observed on a new test sheet. It took about ten minutes to complete it and the same female assistants helped the pre- school pairs to answer the test questions. Week-Later Test Phase Approximately a week after the first phase, participants were asked to take a memory test individually again. Following these Week-later Tests, a questionnaire inquiring whether they had noticed any anomaly in the video presentation was administered. The same female assistants helped the pre-school pairs during this phase. Results Manipulation Check The questionnaire conducted at the week-later phase revealed that no participants noticed any anomaly during the video presentations. The effectiveness of the MORI technique has been shown in various application experiments (French, Gerrie, Garry, & Mori, 2009). It was noteworthy that the present study demonstrated its validity even for pre-school age par- ticipants. Memory Test Scores The memory test scores were converted into percentage scores; that is, the number of items correctly reported divided by the total number of items (= 20) and multiplied by 100. Each test contained three questions concerning the three critical items that had different correct answers depending on which version  K. MORI ET AL. the participant had observed. No significant differences were found between the memory test scores, Immediate or Week- later, of participants who had observed different video versions; F(1,42) = 0.05, ns. Therefore, we combined the data of the two video versions in the following analyses. Figure 2 shows the average memory test scores of pre- school and undergraduate participants for the three test sessions. As expected, the average memory scores of the pre-schoolers were much lower than those of the undergraduates; 53.2 and 84.3, respectively (F(1,88) = 125.56, p < .01; Cohen’s d = 3.16). The results also showed that collaboration had improved the memory test scores for both participant groups (F(2,88) = 7.92, p < .05; d = .61). Tukey’s post hoc test (MSe = 53.5, p < .05) revealed that only the Collaborative Test scores were statisti- cally higher than the other two test scores. The interaction was not significant (F(2,88) = 0.73, ns). Conformity on Week-Later Tests We adopted the same definition of “conformity” as Mori and Kitabayashi (2009). That is, “conformity” was defined as a change in the answers on the Week-later Tests towards the group decision on the Collaborative Tests. A typical example of conformity was when one witness who had answered “white car” on the Immediate Test changed his/her answer to “dark car” on the Week-later Test, after having acceded to their group decision that it was a “dark car” on the Collaborative Test. It was also regarded as conformity when a witness who had no answer on the Immediate Test acceded to the group decision on the Week-later Test. We had intended to examine the conformity frequencies only on the three target items that would cause conflicts between the co-witness pairs. However, we incidentally obtained several conformity responses on some non-target items when one member of a pair overlooked or misperceived information. Some participants made errors or left unanswered some non- target items on the Immediate Tests, and provided on the Week-later Tests answers that had come from the Collaborative Tests. These incidents fit the criteria for conformity as we had defined it. Therefore, we included such items in our analyses of conformity occurrences. The results showed that pre-schoolers tended to conform more than undergraduates on both the target Figure 2. Average memory test scores at the three test periods (max. = 100; ver- tical lines represent standard deviations). and non-target items, as shown in Figure 3. One pre-school pair showed conformity on 2.7 items on average out of 20 (0.7 of the 3 target items) while one undergraduate pair conformed on 1.5 items (0.5 of 3 target items). The Chi-square test per- formed on the total conformity frequency in the two groups showed a significant difference (χ2 (1) = 4.15, p < .05; Cohen’s w = .10). The probability calculation on the conformity frequen- cies based only on the target items showed no significance (p = .42, ns.) Good Conformities vs Bad Conformities As Mori and Kitabayashi (2009) noted in their mother-child pair co-witness conformity experiment, there were good and bad conformities. Conformity may well be a source of distor- tion, as most of the post-event information (PEI) eyewitness literature has demonstrated. However, conformity has positive aspects as well. Witnesses having misperceived the original event may correct their memory through conforming to the correct information (Mori & Kitabayashi, 2009). We observed 50 cases of conformity in total that could be classified either good or bad; “good” if the conformity occurred in the correcting direction, and “bad” if it resulted in a distor- tion. There were ten cases that did not fall into either category, and those were excluded from the analysis. They were mostly for the target items, because there were two correct answers for those. Table 1 shows the frequencies of good and bad confor- mity for child and undergraduate pairs. It showed that good conformity occurred three times more often than bad as a whole (p = .0006, direct probability calculation). It should be noted that the good-bad conformity ratios were similar for children and undergraduates (χ2 = .06, ns). Figure 3. Average number of conformity responses per pair on week-later tests (Each pair reported on the 3 target and 17 non-target items). Table 1. Frequencies of good and bad conformity for pre-school and undergra- duate pairs. Conformity Participants Good Bad Unclassified Total Pre-schoolers 22 6 7 35 Undergraduates9 3 3 15 Total 31 9 10 50 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 33  K. MORI ET AL. Discussion Do Children Really Conform More Often than Adults? The present experiment showed that child co-witnesses con- formed to each other more often than did the undergraduate co-witnesses. This result at first seems a matter of simple com- mon sense. However, we should be cautious about taking these results at face value, because the literature on co-witness re- search has shown conflicting results. For example, Gabbert, et al. (2003) reported that 71% of their undergraduate co-witnesses recalled details that had been acquired during the discussion, whereas in Candel, et al. (2007) only 60% of the child co-wit- nesses (11 - 12 years old) did. A simple comparison of the re- sults of these two studies is inadequate because the conformity indices were different, as were the experimental procedures. As for a genuine comparison under the same conditions, Candel, et al. (2007) concluded that the memory conformity effect was stronger for older children (11 - 12 years old) than for younger (6 - 7 years old). Even this result from a direct comparison within a single study was not consistent with a conflicting re- port by other researchers. Roos af Hjelmsäter, et al. (2008) reported that their 7- and 12-year old children showed no age group difference in their susceptibility to suggestion from adult co-witnesses. Then why did the children in the present experiment conform more? A probable interpretation is that the higher frequency of conformity in children stemmed from the higher rate of mem- ory errors in general. Conformity would only occur when there were some discrepancies among co-witnesses. The more errors there were, the more possibilities for conformity to occur. To state it another way, there might be a “ceiling effect” in the memory performance of the undergraduates. They correctly recalled about 80% on the 20-item cued recall tests, leaving only a small margin for discrepancies among their original answers. As shown in Table 1, three-quarters of conformities occurred in the correcting direction. Our undergraduate co- witnesses did not conform nearly as frequently because they remembered very well what they had observed, leaving little room for amendment. That is why conformity occurred less frequently among undergraduates than among children in the present study. We have some supporting data obtained from a series of dif- ferent, but closely related, recent studies in the Asch conformity experiments. Mori and Arai (2010) replicated the Asch original line judgment experiment without using a confederate by util- izing the MORI technique with foursomes of undergraduate participants. In each foursome of participants, only the third responders wore a different type of polarizing sunglasses than the other three, so that only they observed the lines differently, therefore becoming a minority among the group of four. They found minority female undergraduates made conformity errors in 28.6% of their responses. Using exactly the same experi- mental procedure, Hanayama and Mori (2011) found the corre- sponding error rate of six-year-olds was 50.0%. However, the overall error rate of the child participants was higher than that of the undergraduate participants. Then they estimated the net conformity rates by extracting the error rates of the majority groups from those of the minority groups, obtaining almost equivalent rates for children (50.0 – 21.3 = 28.7%) and under- graduates (28.6 – 8.6 = 20.0%). No Collaborativ e Efforts Shown in the Child Co-Witnesses As described above, our child co-witnesses seemed not to recollect collaboratively what they had witnessed together. We got two clues to that through observation of their behavior dur- ing the Collaborative Test sessions. First, we found that the children were seldom surprised at hearing different answers from their co-viewers. On the contrary, the undergraduate par- ticipants always showed signs of surprise when they experi- enced disagreement on the three differing items. It is quite natural for adult participants to have become puzzled at unex- pected disagreements on such a simple memory test of what they observed together. Secondly, our child co-witnesses did not try to reconcile the discrepancies between their answers. We expected them to discuss the conflicting items and attempt to resolve them, but such discussion seldom occurred among the children during the Collaborative Test sessions. They behaved almost like children at an ice cream shop, where one said “Chocolate” and the other said “Vanilla,” but soon changed to “Chocolate.” These observations were not done systematically, but they implied the interesting interpreta- tion that pre-school children might not have a fully developed Theory of Mind yet. Adult participants started discussion to reconcile the discrepancy when their answers differed each other because they believed their answers should not be differ- ent on something they had witnessed together. It was because they knew what their partner observed and they anticipated certain answers. However, children aged five or so, as in our experiment, seemed lack this sense of reasoning, or inferring what their partners would report. They were not aware of how their co-witness partners had observed the event or how they would answer concerning what they had observed together. Perhaps that is why they were not surprised at the discrepancies they encountered. It is an interesting finding, but it should be examined in detail elsewhere rather than in the present study. Further well-constructed research on this interesting interpreta- tion would be illuminating. Is the Collaboration of Co-Witnesses Good or Bad? Implications for Forensic Practices It would be rather difficult to give concrete implications from the present study for forensic practice on co-witness effects. However, it clearly showed that collaboration of co-witnesses may lead to better memory performance. It was repeatedly shown in the experimental studies utilizing the MORI method (Kanematsu, et al., 1996/2003; Matsuno, et al., 2005; Mori & Kitabayashi, 2009). That was mostly because witnesses may well be mutually reminded of the correct information by their partners if they collaborate. We also found that conformity after the collaborative recollection may occur in the correcting direc- tion more often than in the distorting direction. These findings showed the positive side of collaboration among co-witnesses. However, a negative side of collaboration was found, too. If one of the co-witnesses misperceives or miscomprehends some detail and insists, discussion may become a two-edged sword. The mistaken details may be corrected through discussion, but, alternatively, they may well persist and become reinforced even though they are incorrect. Though, it was less frequent, we did find that some conformities resulted in wrong answers. The problem is that, when it comes to actual co-witnesses, we never know which may occur. Therefore, we cannot present here any Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 34  K. MORI ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 35 definitive recommendation on whether or not co-witnesses should be allowed to discuss their observations. Acknowledgement This research was done while the authors were at Shinshu University. It was supported by a Grant-in-Aid from the Japa- nese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (Grant No.13610081) to the first author. We thank all the children and teachers in Hiraoka Nursery School in Na- gano Prefecture for their cooperation in the conduct of this research. The animation was made by Akane Yamazaki for her capstone thesis submitted to Shinshu University in 2002. We are indebted to Rebecca Ann Marck for her superb work in editing the English manuscript. REFERENCES Candel, I., Memon, A., & Al-Harazi, F. (2007). Peer discussion affects children’s memory reports. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 21, 1191- 1199. doi:10.1002/acp.1355 Davies, G., & Pezdek, K. (2010). Children as witnesses. In G. J. Towl, & D. A. Crighton (Eds.), Forensic psychology (pp. 178-193). Leicester, UK: BPS Blackwell. French, L., Garry, M., & Mori, K. (2008). You say tomato? Collabora- tive remembering between intimate couples leads to more false memories than for strangers. Memory, 16, 262-273. doi:10.1080/09658210701801491 French, L., Garry, M., & Mori, K. (2011). Relative—Not absolute— Judgments of credibility affect susceptibility to misinformation con- veyed during discussion. Ac ta Psychologica, 136, 119-128. doi:10.1016/j.actpsy.2010.10.009 French, L., Gerrie, M. P., Garry, M., & Mori, K. (2009). Evidence for the efficacy of the MORI technique: Viewers do not notice or im- plicitly remember details from the alternate movie version. Behavior Research Methods, 41, 1224-1232. doi:10.3758/BRM.41.4.1224 Gabbert, F., Memon, A., & Allan, K. (2003). Memory conformity: Can eyewitnesses influence each other’s memories for an event? Applied Cognitive Psychology, 17, 533-543. doi:10.1002/acp.885 Gabbert, F., Memon, A., & Wright, D. B. (2007). I saw it for longer than you: The relationship between perceived encoding duration and memory conformity. Acta Psychologica, 124, 319-331. doi:10.1016/j.actpsy.2006.03.009 Hanayama, A. & Mori, K. (2011). Conformity of six-year-old children in the Asch experiment without using confederates. Psychology, 2, 661-664. doi:10.4236/psych.2011.27100 Matsuno, E., Mori, K., Hirokawa, K., & Ukita, J. (2005). The effects of gender differences in pairs of eyewitnesses on recall memory. Japa- nese Journal of Cognitive P sy c h ol o g y, 3, 83-94. doi:10.5265/jcogpsy.3.83 Kanematsu, H., Mori, K., & Mori, H. (1996/2003). Kotonaru Jitai wo mokugekishita futari no mokugekisha no hanashiai niyoru kioku no hen-you [Memory distortion in eyewitness pairs who observed non- conforming events and discussed them]. Cognitive Studies: Bulletin of the Japanese Cognitive Science Society, 3, 29-40, 1996. (In Japa- nese. English version published in Journal of the Faculty of Educa- tion, Shinshu University, 10 9, 75-84, 2003). Mori, K. (2003). Surreptitiously projecting different movies to two subsets of viewers. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, and Computers, 35, 599-604. doi:10.3758/BF03195539 Mori, K. (2007). A revised method for projecting two different movies to two groups of viewers without their noticing the duality. Behavior Research Methods, 39, 574-578. doi:10.3758/BF03193028 Mori, K., & Arai, M. (2010). No need to fake it: Reproduction of the Asch experiment without using confederates. International Journal of Psychology, 45, 390-397. doi:10.1080/00207591003774485 Mori, K., & Kitabayashi, M. (2009). How child-mother pairs reported what they had witnessed together: An experimental examination us- ing the MORI technique. Ps ych olog y Jo urn al, 6, 60-69. Mori, K., & Mori, H. (2008). Conformity among cowitnesses sharing same or different information about an event in experimental col- laborative eyewitness testimony. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 106, 275-290. doi:10.2466/pms.106.1.275-290 Roos af Hjelmsäter, E., Granhag, P. A., Strömwall, L. A., & Memon, A. (2008). The effects of social influence on children’s memory reports: The omission and commission error asymmetry. Scandinavian Jour- nal of Psychology, 49, 507-513. Wright, D. B., Memon, A., Skagerberg, E. M., & Gabbert, F. (2009). When eyewitnesses talk. Current Directions in Psychological Sci- ence, 18, 174-178. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01631.x

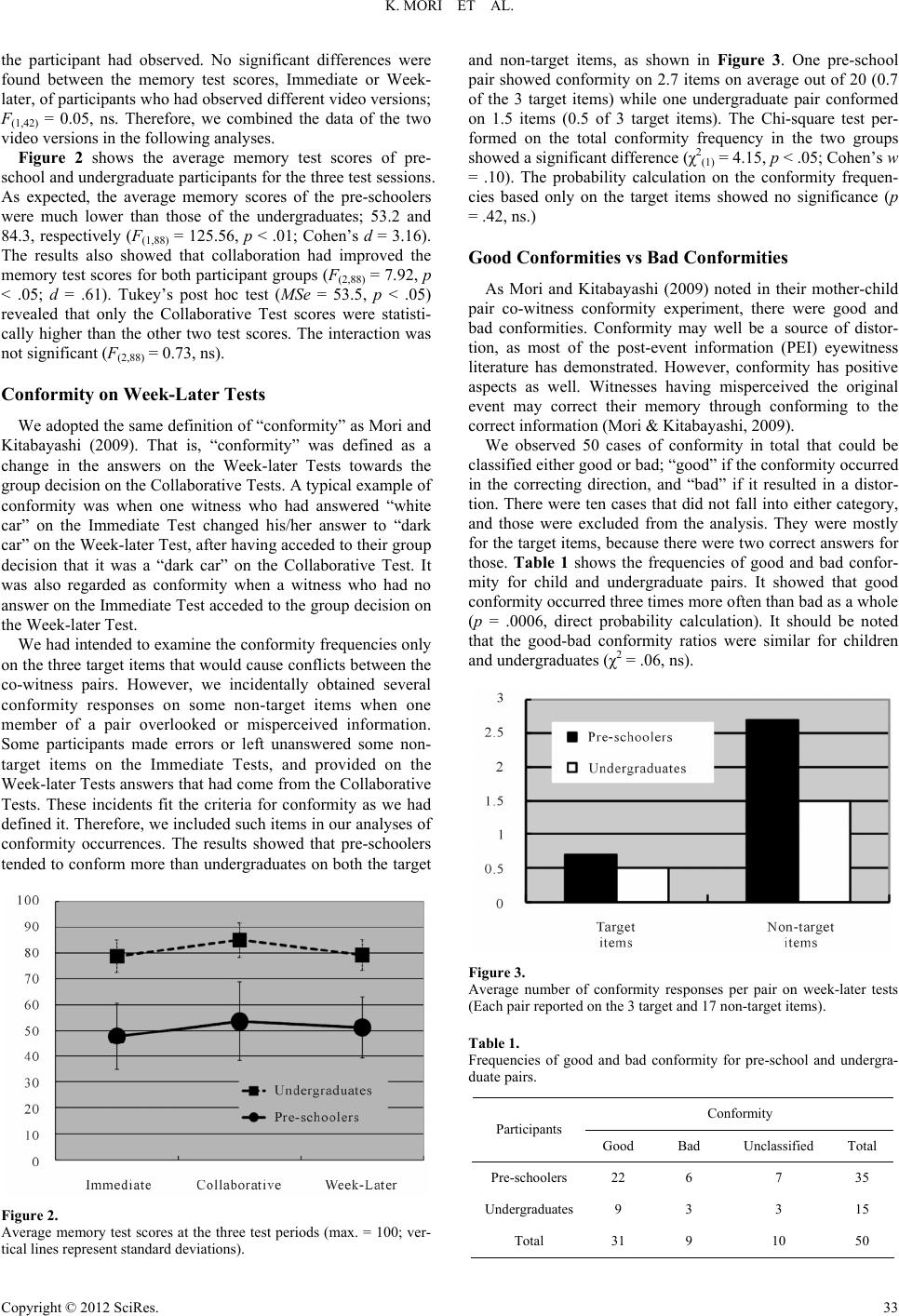

|