Psychology 2012. Vol.3, No.1, 90-99 Published Online January 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/psych) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/psych.2012.31015 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 90 Collective and Personal Annihilation Anxiety: Measuring Annihilation Anxiety AA Ibrahim A. Kira1, Thomas Templin2, Linda Lewandowski2, Vidya Ramaswamy2, Bulent Ozkan2, Jamal Mohanesh3, Abdulkhaleq Hussam3 1Center for Cumulative Trauma Studies, Stone Mountain, USA 2Wayne State University, Detroit, USA 3ACCESS Community Mental Health and Research Center, Dearborn, USA Email: kiraaref@aol.com Received October 21st, 2011; revised November 24th, 2011; accepted December 26th, 2011 AA is defined in the psychoanalytic literature as fear of impending psychic or physical destruction that is triggered by personal survival threats. Little or no attention in the psychoanalytic literature was given to collective or group survival threats. We developed a short measure for AA that includes both kinds of survival threats. We used a clinical sample of 399 mental health clients and measures for cumulative trauma, PTSD, cumulative trauma related disorders, depression and anxiety. We conducted confirmatory factor analysis, multiple regressions, and path analysis. The developed short measure has good reliability, strong divergent and predictive validity and generally fit the theoretical assumptions that underlie the construct. The measure can be useful in clinical screening, and in psychological and political research, especially with the multiply traumatized. Subsequent research that utilized the measure replicated the findings. Keywords: Collective Identity; Annihilation Anxiety; Identity Threats; Collective Annihilation Anxiety; Identity Salience; Mortality Salience Introduction Definitions and Theory Annihilation Anxiety AA was introduced in psychoanalytic, ego, self-psychology, and object relations psychology literature (e.g., Hurvich, 1989, 2003). However, the construct goes back to existential philosophies of Sartre and Heidegger (e.g., Petot, 1976). According to Hurvich, 2003, Annihilation anxieties are defined as an individual subjective fear of impending psychic or physical destruction that are triggered by personal survival threats (Hurvich, 2003). AA is found to be associated with dis- rupted ego functioning and poor ego development, panic, de- pression, inability to function, avoidant behavior, self-destruc- tion or self-injurious behavior (e.g., Hurvich, 2003; Borg, 2003; Cassidy-Charren, 2003). Many authors early identified AA through the clinical presentation of schizophrenia, borderline and psychotic disorders (e.g., Rosenfeld, 1950; Teixiera, 1948). AA is considered to be a key component of post-trauma re- sponse (Miller, 2001). AA as defined in psychoanalytic litera- ture, has individualistic bias, as it is focused on the individual’s concerns for his/her personal survival and put less or no em- phasis on such feeling resulted from Individual’s concern for threats to her/his own collective or group survival. AA is defined by authors is a chronic terror of losing per- sonal or social self or selves as a result of identity, personal or/ and collective/ group’s survival threats. AA emerges from fears that one or more of the self salient identities will be subsumed, devoured, dissolved or fused, penetrated, fragmented, destroyed, disappeared or subjugated, due to real or perceived threats to such salient identities’ survival. Identity salience, personal and collective, is a strong explanatory paradigm for AA (Kira, 2002, 2006; Smith, 1999). Individual’s Identity that has developed through the individuation process shapes the individual’s feel- ings of existential belonging to self, family and groups. Differ- ent kinds of existential identity survival threats can cause dif- ferent types of AA. Primary appraisals involve judgments about whether the in- dividual or his affected group is in jeopardy, whereas secondary appraisals involve judgments about the group or individual potential self-efficacy in responding to the event. (e.g., Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). The individual’s appraisal of his/her self is related to perception of self-efficacy and adequacy (secondary appraisal). AA is related to the secondary appraisal process of trauma, i.e., appraisal of self-efficacy. Such appraisal, when positive, produces feelings of agency and self-efficacy (c.f., Bandura, 1997), when it is negative may produce distress and AA. Trauma theories distinguish between two types of identity trauma with relevant identity threats and related levels of AA: 1) AA that results from personal identity trauma. Personal identity traumas violate personal autonomy, self-control and self-efficacy, for example rape or sexual abuse. It may include some debilitating illness and serious disabilities that result loss of functioning and dependence on others. 2) AA that result from collective identity trauma. According to self-categorization theory (e.g., Turner, 1985), and to inter- group emotions theory (Smith, 1999), when social identity is salient, group members perceive themselves as exemplars of the group and events that harm or favor the group harm or favor the self. When social identity is salient, appraisal of events relevant and important to the group focuses on social rather than personal concerns. Group-based appraisals elicit specific emotions and action tendencies (Smith, 1999). Group members  I. A. KIRA ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 91 feel happy, sad, or traumatized depending on the successes or failures of the in-group with which they identify, even if they do not personally contribute to that outcome (Cialdini, et al., 1976). In the case of collective identity traumas, the effects of per- ceived in-group strength or efficacy on offensive and revenge action tendencies (secondary appraisal) are mediated by anger (Mackie, Devos & Smith, 2000). Conversely, in the event of negative appraisal of the group strength or vulnerability (group efficacy) in severely traumatized and minority groups, fear of annihilation, feelings of humiliation, subjugation, distress, and other negative emotions can erupt (e.g., Kira, 2002; Kira, et al., 2008). Minority groups and oppressed are likely to have less perceived efficacy compared to dominant groups, which are associated with increased AA feelings when confronted with such events. Extreme examples of such threats are nuclear an- nihilation threats that are posed directly or indirectly to a nation or to species (e.g., Olsen, 1984). Holocaust for Jewish people (e.g., Garwood, 1996, and the collective threats to the Jews and Palestinians (Kira, 2006; Kira, et al., 2007) are other examples. Such threats to the existence of such groups can activate group identity salience and deactivate personal identity and mortality salience causing terror and fear of group annihilation (Kira, 2002, 2006). While the concept of general anxiety measured in clinical psychology represents general psychological and physical symptoms that may be triggered by different general concerns, AA belongs to different category of anxieties that are specific and triggered by specific identity survival threats. AA is as- sumed to predict general anxiety, and to have more severe con- sequences than general anxiety. Focusing on AA as specific anxiety resulted from identity survival’s threats, can enrich empirical and clinical research by focusing on the etiology of symptoms. Identifying the underlying annihilation anxieties, that may be key contributors to the emergence and maintenance of post-identity trauma symptoms, may help better address them. It may be useful to tie psychoanalytic and cognitive appraisal perspectives on evaluating the clinical utility and measuring the AA concept. AA is almost ignored in the mainstream clinical and cognitive psychology as well as in traumatology. It may be worthwhile to develop this initially psychoanalytic construct and integrate it in the mainstream clinical, political, cognitive and trauma psychology disciplines. In the next sections we will briefly discuss the issues relating to AA and trauma measure- ment. Measuring AA The psychoanalytic literature focused more on defining and measuring AA that result from threats to dependency and or threats to personal identity. They used a projective Rorschach sub-test to measure the construct (e.g., Benveniste, Papouchis, Allen & Hurvich, 1998). Rorschach and projective measures, while attractive, is hard to use in research with large samples. A self-report measure for AA, Hurvich experience inventory HEI has been constructed by Hurvich (1998). HEI was found to have weak association with Rorchach AA sub-scale (Ben- veniste, Papouchis, Allen, & Hurvich, 1998). HEI may have some problems with its face and construct validities. Some of its items represent potential outcome for AA, rather than AA per se. For example it includes items about nightmares which are part of PTSD concept. Other items of HEI ask about panic, dissociation, fear of death, anxiety for being alone. Such items made it contaminated and difficult to use to measure its asso- ciation with such constructs such as PTSD, depression, disso- ciation, panic attacks, fear of death and general anxiety. Fur- thermore, the measure does not include items that represent the other types of threat that may activate AA such as collective threats. On the other hand, measuring AA in severely trauma- tized population, for example refugees and torture survivors, are challenging. Some of the most severe threats to their iden- tity are collective identity threats. A brief screening measure for AA that include collective or group identity threats can be more useful in clinical settings as well as in research with severely traumatized populations and in political psychology. Method Research Questions Is the concept of AA useful and can be measured and used to predict negative mental and physical health outcomes to differ- ent traumas and their appraisal in clinical and research settings. Is the AA related to collective identity important component of AA construct? Research Hypotheses Hypothesis 1: The multi-component construct of AA as measured by the brief three items scale, developed in this study, is valid and reliable. Hypothesis 2: AA is unique but significantly correlated to general anxiety. Hypothesis 3: Different traumas that threaten personal and collective identities predict AA. Hypothesis 4: Negative appraisal is stronger predictor of AA than the sheer occurrence of the traumatic event. Hypothesis 5: AA predicts poor mental and physical health. Hypothesis 6: AA mediates the effects of different traumas on mental and physical health and on suicidality. Participants Participants were 420 adult mental health clients in a clinic in Dearborn Michigan that constitute all active clients that came for a psychiatrist, therapist, or case manager visit during the 6 month from August 2004, to February 2005, and who accepted and consented to participate (90%). Twenty one of the ques- tionnaires, when screened, found to be questionable and ex- cluded and 399 remained as participants. The sample included 82.7% mental health patients from Arab American and Iraqi refugees (highly traumatized from collective cultures), and 17.3% from non-Arabic origins. Age ranged from 18 - 76, with mean of 39.66 and SD of 11.45. It included 53.5% males and 46.5% females. Nineteen percent of the participants (76 par- ticipants) reported the experience of torture in their own coun- try of origin. For the length of stay in US, the average was 3.24 years of stay with SD of 2.13. Table 1 details the distribution of employment, marital status, length of stay in US, citizenship, education, and religious affiliations. Procedure Informed consents were obtained from adult participants. No  I. A. KIRA ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 92 Table 1. The distribution of employment, marital status, length of stay in us, citizenship, education, and religious affiliations. Demographic Variable % Demographic Variable % Employment status: unemployed or on disabilities 51% Citizenship or immigration status: residents 32.2% Employment status: Employee for organizations 5.5% Citizenship or immigration status: citizen by naturalization 23.4% Employment status: homemakers or house wives 19.5% Citizenship or immigration status: citizen by birth, 9.6% Employment status: professionals 3.4% Citizenship or immigration status: others. 3.6% Employment status: retired 5.7% Education: Illiterate 14.2% Employment status: other kinds of employment 14,9% Education: Elementary School 27.5% Marital status: Married 70% Education: Intermediate to Junior high 36.9% Marital status: Single 17.3% Education: High School 16.5% Marital status: Separated 2.5% Education: University Graduates 4.9% Marital status: Divorced 7.6% Income: less than 5,000$ a year, 47% Marital status: Other 2.5% Income: less that 25,000$ a year 95% Length of Stay in US: 2 years or less 26.9% Religious affiliation: Muslims 84% Length of Stay in US: three years 38.3% Religious affiliation: Christians 12.5 % Length of Stay in US: four years 25.1% Religious affiliation: Jewish 1% Length of Stay in US: 5 years or more 9.8% Religious affiliation: others. 2.5% Citizenship or immigration status: refuges from Iraq 31.2% identifying information, linking subject to the data, was re- corded and the disclosure of the data could not reasonably place the subjects at any risk for any liability. Interviews were con- ducted face to face by clinicians. Participants gave the choice between being interviewed in Arabic or English. The data col- lected was part of approved study of the effects of mental health stigma and stigma consciousness to evaluate an anti- stigma intervention. The data collection continued from No- vember 2004 to February 2005. Measures Process and Criteria for Developing and Using Measures In this study, close attention was paid to developing and us- ing measures that would be reliable, valid, and culturally-ap- propriate for this refugee and clinical populations. Several of the tools used in this study as identified in the fol- lowing section, have previously been shown to have adequate reliability and validity on Iraqi and Arab populations and in Arabic and English languages (e.g., Kira, et al, 2001, 2006, 2008). One of the rules we adopted in designing the current scale is the law of parsimony, which required that we choose the least number of questions without compromising reliability or validity. This rule needs to be adopted especially in the case of refugees and highly traumatized populations as their atten- tion span and tolerance for long questioning may be limited and can cause high rates of missing or unreliable data. Chochinov, Wilson, Enuus, & Lander (1997), in a landmark study on ter- minally ill subjects, found that a single item measure of depres- sion had more predictive power for a diagnosis of depression in this population than other longer clinical tools including the Beck Depression Inventory. That may mean that single item and short measures that reduce subject burden, can be reliable and have high predictive power. The new measures for this study were first constructed in English and subsequently translated into Arabic by three bilin- gual mental health professionals who each individually trans- lated the measures and then met together to establish a consen- sus on the final version based on the criteria of adequate cul- tural sensitivity and appropriateness in measuring the construct of the instrument.. A fourth mental health professional did the reverse translation. These measures were pilot tested in focus groups. The measures used in the current study include: Independent Variable Measures Cumulative Trauma Scale and Its Sub-Scales The measure includes 61 items. Each item describes ex- tremely stressful event. The participant was asked to report if he/she experienced it or not, how many times he have experi- enced the event, at what age first time, and how much it af- fected him positively or negatively on a scale from 0 to 7. The measure provides us with general scales for two of cumulative Trauma doses: Occurrence and frequency of happenings, two appraisal sub-scales: negative and positive appraisal. It includes, at this level, four sub-scales for each trauma types. Trauma types include according to Kira’s taxonomy of trauma (Kira, 2001, 2004; Kira, et al., 2008a; Kira, et al., 2011a): Collective identity, personal identity, attachment, interdependence, physi- cal survival, and self-actualization. For the purpose of this study we focused on cumulative trauma occurrence and its cumulative tertiary negative appraisal (CTNA) for the general scale and for the 6 trauma types (14 sub-scales). The measure  I. A. KIRA ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 93 and it subscales proved in previous and subsequent studies to have good alpha reliability coefficients that ranged between .89 and .98, construct and predictive validity (Kira, et al., 2008a, 2008b). Alpha coefficients in the current data are .92 for cumu- lative occurrence, .98 for cumulative positive appraisal (CTPA), and .88 for cumulative negative appraisal (CTNA). Its sub- scales alpha reliability coefficients ranged from .70 - .92. Dependent Variable Measures Annihilation Anxiety Scale (AA) (3 items) The measure is based on the assumption that there are at least three main sources of the emergence of annihilation anxiety, personal identity, collective identity survival threats (traumas) as well as threats from societal structural inequalities, for ex- ample extreme poverty (Kira, 2004; Cassiman, 2005). These three sources represent the different sources of AA we dis- cussed earlier. An item that represents each area of annihilation concerns was chosen from 10 suggested items for each area by a group of five clinicians. A three items that represents the three components were chosen to include the following 5 point- Likert-type questions: 1) Because of what has happened to me personally or is hap- pening to me personally, I sometimes worry that I just lose my sense of self (I worry that I will cease to exist as an individual person). 5. Strongly Agree 4. Agree 3. Not sure 2. Disagree 1. Strongly Disagree 2) Sometimes I feel the threat of extermination/annihilation (that is, the threat of termination or “getting rid of” or ultimate subjugation) of my group because of discrimination or stereo- typing or acts committed against me, my race, religion, culture, or ethnic group. 5. Strongly Agree 4. Agree 3. Not sure 2. Disagree 1. Strongly Disagree 3) I feel threatened by extreme inequalities in this society. 5. Strongly Agree 4. Agree 3. Not sure 2. Disagree 1. Strongly Disagree PTSD Measure (CAPS-2) (18 items): This measure was de- veloped by Blacke et al. (1990) and is widely used to assess PTSD. It is a structured clinical interview that assesses 17 symptoms rated on frequency and severity on a 5-point scale. CAPS demonstrated high reliability with a range from 0.92 - 0.99 and showed good convergent and discriminant validity (Weathers, Keane & Davidson, 2001). In this study, we used the frequency sub-scale of CAPS-2 that is currently widely used in psychiatric literature. The scale used in this study has high reliability with an alpha of 0.97. The scale has four sub- scales: re-experiencing, avoidance, arousal and dissociation. Reliability of the four sub-scales in current sample are adequate to high (alphas are .96, .92, .89 and .85 respectively). Cumulative Trauma Disorders Measure CTD (15 items). The measure has been developed on several community and clinic samples on adults and adolescents Iraqi refugees and Arab Americans. It is an index measure that covers 13 different symptoms: depression, anxiety, somatization, dissociation, auditory and visual hallucinations, avoidance of being with people, paranoid ideations, concentration and memory deficits, loss of self control, feeling too harsh with family, and with people in general, feeling suicidal, and feeling like hurting self. Exploratory factor analysis found four factors (sub-scales): Executive function deficits, suicidality, dissociation/ psycho- tism, and depression/ anxiety interface. Reliability of the four sub-scales found to be high (.95, .97, .98, and .96 respectively). Confirmatory factor analysis confirmed this structure in a dif- ferent sample. The measure has good reliability (ranged from .85 and .98), construct, and convergent, divergent and predictive validity. Test-retest reliability in a 6 week-interval is .76. Different kinds of traumas, and cumulative trauma in general accounted for significant variance as predictors of CTD symptoms (Kira, 2004; Kira, Clifford, Wiencek, & Al-haider, 2001; Kira, Clifford, & Al-Haider, 2002, 2003). It has alpha reliability coefficient of .91 in the present study. CES-D Depression Measure: Center for Epidemiologic stud- ies-Depression mood scale is a 20 item scale (Radloff, 1977). Each item is assessed on a 4-point scale and reflects the fre- quency that each symptom is experienced (0 = none of the time, 3 = all of the time). Adequate reliability and validity have been reported for the CES-D. A cutoff score of ≥16 is commonly used for the CES-D to indicate a need for further assessment of the presence of MDD (Radloff, 1977). High internal consis- tency reliability results (ranging from .85 to .92) have been found for the CES-D among various age, sex, geographic, and racial-ethnic subgroups. Validation studies have found that the CES-D has good convergent validity, discriminant validity (Himmelfarb & Murrell, 1983), and sensitivity and specificity (Mulrow, et al., 1995). It has alpha reliability coefficient of .91 in the present study. Depression, Anxiety Stress Scales. Anxiety (DASS-A) Anxi- ety Measure (14 items): DASS is a 42-item scale developed by Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995, and includes three sub-scales that measure depression, anxiety, and stress. DASS- A sub-scale measures anxiety, which is increasingly used in different clini- cal and research settings. Different studies suggest that DASS- A possess adequate convergent validity, with reliability of .84 in non-clinical samples and .89, and 91 in clinical samples (e.g., Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995). Its alpha reliability in the present study is .95. Self-rated health SRH is measured by a single item question about general health. The question asks to rate your general health according to five Point Likert-type scales (excellent, good, fair, poor, very poor). Following Wanous and Hudy’s (2001) method of estimating single-item reliability using factor analysis, the reliability of the SRH scale was .77 (communality of the item). Factor analysis was conducted between the item and other health problems in a previous study on the same population (Kira, et al., 2006). Using the correction of attenua- tion formula, reliability is estimated to be between .78 (Con- servative) and .87 (liberal). The item correlation using the full 12 items health scale (that includes a list of health conditions) in a previous study was .91. Analysis We calculated Alpha reliability for the three item scale, and for all scales that we utilized. We conducted test-re-test reli- ability of AA’S on a small sample (n = 30) after 4 weeks. We conducted exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis using general anxiety scale (DASS-A) and AA together to test the independence of AA construct compared to general anxiety and to explore its construct and divergent validity. We tested AA predictive validity through using multiple regression analysis with AA as independent variable and depression, poor health, PTSD, and general anxiety as dependent variables, controlling for demographics. To test the hypothesis that specific trauma types, and high trauma dose predicts AA, we conducted a series  I. A. KIRA ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 94 of multiple regression with trauma dose, trauma types and negative appraisal of different traumas as independent variables and AA as dependent variable controlling for demographics. We used SOBEL test (using SPSS macro with bootstrap, num- ber of repetitions = 10.000) to examine the potential significant indirect effects of AA on suicidality through the mediation of depression, Anxiety, PTSD and other CTD sub-scales. The proposed path models were evaluated using structural equation modeling (SEM) with AMOS 7.0 (Arbuckle, 2006). We constructed hybrid models that used latent and observed variables. A satisfactory model fit is indicated by a no signifi- cant Chi Square (although significant values are acceptable when the sample size is large, which is the case in the current sample) (see Hu & Bentler, 1999). Accordingly, we tested the path models of AA as mediator of the effects of specific trauma type’s occurrence and their CPTA and CNTA on different mental health conditions as well as on general health. To ex- amine the mediation hypothesis we used bootstrap (N = 200) with bias-corrected confidence intervals to tests the significance of the direct and indirect effects of each predictive variable (e.g., Erceg-Hurn & Mirosevich, 2008). Results General: Using ANOVA to test the differences between refugees, permanent residents, naturalized citizens and citizens by birth in AA, refugees have significantly higher scores of AA compared to the other groups with no significant differences between the other three groups (refugees: N = 114, M = 11.33, SD = 3.12; Permanent residents: N = 108, mean = 8.69, SD = 3.84; naturalized citizens N = 82, M = 8.51, SD = 3.47; Citizens by birth = 35, M = 8.11, SD = 3.43; Total mean score for the sample M = 9.50, SD = 3.62; p < .000). The scores are high for all groups in this sample of mental health clients’ considering the maximum score is 15. No significant differences found between age groups, education, marital status or gender catego- ries in AA. The mean number of life-time trauma types the participant endured is 10.34 with SD of 7.70. The refugees has the highest cumulative trauma dose with mean of M = 11.46 and SD of 6.68, compare to all others (M = 9.77, SD = 8.12), and naturalized citizens (M = 8.48. SD = 8.51) and the differ- ences are statistically significant. Hypothesis 1: Alpha reliability of the three item AA scale is good (.93). It proved to have good concurrent and predictive validity. Test-re-test after four weeks (N = 30) reliability is .73. Principal component factor analysis, using Kaiser Criteria of Eigen value of 1 for factor extraction, found a single factor accounted for 86.50% of the variance. The loading of each item on the factor was above .90. The communality of each item was above .80. AA scale has good convergent validity as it is highly posi- tively correlated with PTSD (.50), CTD (r = .45, p < .000), depression (r = .49, p < .000) and general anxiety (r = .341, p < .000), and stigma of mental illness (r = .48, p < .000). It cor- related highly with dissociation psychosis sub-scale of CTD (r = .51, p < .000). These correlations confirmed the theoretical assumptions about the prediction of AA (e.g., Hurvich, 2003) as it is associated with dissociation and psychosis. Hypothesis 2: Because we assumed that AA and general anxiety (A), though correlated empirically is unique conceptu- ally, we conducted factor analysis for the A and AA items to- gether (17 items) using principal component with Kaiser Nor- malization and Varimax orthogonal rotation. We found two unique factors accounted for 64.870% of the variance. The first loaded on all general anxiety items and second loaded only on all the AA three items. AA items loaded the highest and have the highest communality. Table 2 presents each item statistics factor loadings and communalities. Hypothesis 3 and 4: Multiple regression analyses conducted with AA as dependent variable and other types of trauma dose and negative appraisal as independent variables. We added demographics to the independent variables list to control for their effects. All types of trauma and cumulative trauma dose and their negative appraisal highly predicted AA. The most predictive trauma was collective identity trauma (β =.74). Fur- ther, the results confirmed that negative appraisal of different survival and identity traumas were stronger predictor of AA than the occurrence of the traumas. These findings give cre- dence to the differential cognitive appraisal hypothesis among this adult population. Table 3 describes these results. Hypothesis 5: Multiple regression analysis with AA as inde- pendent variable and PTSD, CTD, CES-D, DASS-A, their sub- scales and self-rated poor health as dependent variables, con- trolling for demographics, found that AA is a significant pre- dictor of PTSD (β = 46), CTD (β = 43), general anxiety (β = .40), depression (β = .38), and poor self-rated health (β = .14). AA was found to be a significant predictor of all PTSD, DASS-A, and CTD. The results generally confirm hypothesis four. Table 3 describes these results. Hypothesis 6: Using SEM hybrid Path analysis model, we tested different mediation models that have good fit. Each model we tested has personal identity, collective identity, sur- vival, secondary trauma, or cumulative negative appraisal, as predictive variables. Each predictive variable in these models has direct positive assenting effects on AA, and on mental health syndrome (a latent variable which is predicted by PTSD, depression, and general anxiety), and indirect effects on mental and physical health as observed outcome variables. The effects were mediated by AA. All models tested have good fit with significant direct effects of the independent variables on AA and mental health syndrome and indirect effects on the other outcome variables as mediated by AA. We will present in detail the models, in which the predictive variables: Cumulative nega- tive appraisal and collective identity negative appraisals, has the strongest effect on AA and on the other physical and mental health variables. In the first mediation model, cumulative negative appraisal was the predictive variable in the model. AA mediated the ef- fects of cumulative negative appraisal on mental health syn- drome (a latent variable in the model) and on physical health. PTSD accounted for the highest variance in the model (squared R = .691) followed by CTD (squared R = .574). The model has good fit (Chi Square = 37.540, d.f. = 12, p = .000, CFI = .972, RMSEA = .073). Table 4 presents the direct, indirect and total effects of each variable of the model. All effects are statistically significant. The second mediation model has the best fit (Chi Square = 38.547, d.f.= 12, p = .000, CFI = .980, RMSEA = .075). In this model, we used collective identity trauma CIT as the only in- dependent variable in the model. CIT has direct effects on AA, and Mental health syndrome MHS (a latent variable in the model). AA mediated CIT effects on mental health syndrome and physical health. AA explained the highest variance in this model (R squared = .754). Figure 1 presents the path model  I. A. KIRA ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 95 Table 2. Rotated Component Matrix for the general anxiety (GA) and AA items: Extraction Method: Principal Component Analysis. Rotation method: varimax with kaiser normalization. Factor Loading Item Statistics 1 (GA)2 (AA)Mean SD Communalities I felt terrified .855 −.023 1.53 1.11 .732 I was worried about situations in which I might panic and make a fool out of myself .835 −.066 1.41 1.07 .702 I experienced trembling .834 .001 1.37 1.04 .695 I felt like I was close to panic .826 .010 1.33 1.05 .683 I feared that I would be thrown by some trivial but unfamiliar task .820 .011 1.32 1.03 .673 I experienced breathing difficulty .799 .085 1.35 1.10 .646 I had a feeling of shakiness .784 .106 1.28 1.07 .626 I was aware of the action of my heart in the absence of physical exertion .764 −.005 1.28 .99 .584 I had a feeling of faintness .761 .027 1.22 1.06 .560 I felt scared without any good reason .749 .101 1.56 1.10 .571 I found myself in situations that made me so anxious .734 .145 1.45 1.04 .560 I perspired noticeably .687 .135 1.29 1.03 .490 I had difficulty in swallowing .682 .065 1.04 .98 .469 I was aware of my dryness in my mouth .633 .116 1.42 1.13 .414 Sometimes I feel the threat of extermination/ annihilation to my group… .045 .944 3.11 1.31 .893 I feel threatened by extreme inequalities in this society. .056 .942 3.15 1.26 .891 Because of what has happened to me personally or is happening, I sometimes worry that I will just lose my sense of self or cease to exist. .075 .901 3.17 1.31 .818 Factor Eigen value 8.422 2.605 Total Variance Factor variance 49.544 15.326 64.870 and Table 6 presents the direct, indirect and total effects of each variable of the model. All effects are statistically signifi- cant. Alternative models: Care must be taken when making causal inferences from cross-sectional data. The theoretical argument for the proposed models is strong and the model fitted the data well; however, there are always alternative models (MacCallum & Austin, 2000). We considered several alternative models in which we changed the order of the predictors, mediators, and outcome variables. In the first alternative model (AM), we considered general health (GH) a mediator and AA and MHS the outcome variables. In the second AM, we considered MHS a mediator and GH the outcome variable; in the third AM, we considered MHS a mediator and AA and AA and GH the out- come variables. In the fourth AM, we considered general anxi- ety (GA) a mediator and MHS-GA, AA, and GH the outcome variables; in the fifth AM, we considered PTSD a mediator and MHS-PTSD, GH and AA the outcome variables; in the sixth AM we considered CTD a mediator and MHS-CTD, AA, and GH the outcome variables. In the seventh AM, we considered depression (D) a mediator and MHS-D, GH and AA the out- come variables. All the seven AM have poor fit indexes and are not viable models. Conclusions and Discussion This short measure of Annihilation Anxiety (AA) has good reliability and adequate divergent and predictive validity and generally fit the theoretical assumptions that underlie the con- struct we presented in the introduction and in the psychoana- lytic literature. The results provide another aspect in the con- cept that was not adequately addressed in the psychoanalytic literature, which is the annihilation anxiety related to collective identity threats, rather than only threats to personal identity. The measure seems to address both terrors come with threats to collective and personal identity. However, in the population we conducted our study, the AA that emanated from the collective threats seems stronger than those of personal identity treats or other traumas. Results confirmed our first and second hypothesis as the short measure developed in the current study is reliable Alpha = .93, test re-test, R = .76) and has good construct and divergent validity. Confirmatory factor analyses have indicated that AA constitutes a separate factor different from general anxiety. The results confirmed hypothesis 3 and 4 as different traumas that threaten identity especially collective identity predicted AA. While the occurrence of such traumas predicted AA, their  I. A. KIRA ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 96 Table 3. The effects of cumulative trauma and trauma types’ dose and negative appraisal on AA. Self-annihilation Anxiety B SE Beta P TD a .20 .03 .40 .00001 NACTD a .15 .01 .59 .00001 CITD a .58 .032 .74 .00001 NACIT .58 .03 .74 .00001 ATD a −.06 .34 .01 .86 NAAT a −.02 .23 −.004 .944 PITD a .74 .11 .40 .00001 NAPIT a .42 .04 .55 .00001 STD a .49 .09 .33 .00001 NAST a .31 .03 .47 .00001 ITD a 1.10 .11 .53 .00001 NAIT a .45 .03 .63 .00001 TD = Cumulative Trauma Dose, NACTD = Negative appraisal of cumulative trauma, CITD = Collective Identity trauma dose, NACIT = Negative Appraisal of collective Identity Trauma, ATD = Attachment Trauma dose, NAAT= Negative appraisal of Attachment trauma, PITD = Personal identity Trauma Dose, NAPIT= Negative Ap- praisal of personal Identity Trauma, STD = Survival Trauma Dose, NAST = Negative Appraisal of survival trauma, ITD = Interdependence Trauma Dose. NAIT = Nega- tive Appraisal of interdependence Trauma; (a) Findings are obtained after the effects of gender, age, marital status; education and income were controlled statistically. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001. a) n = 399. Table 4. The effects of AA on self-rated health and mental health variables (a). Dependent variables B SE Beta P Poor Health .03 .01 .14** .002 DASS-A: General Anxiety 1.18 .14 .40**** .000 DASS-A-Physical .47 .07 .33**** .000 DASS-A-Psychological .88 .09 .45 .000 Depression 1.21 .15 .38**** .000 PTSD 3.22 .31 .46**** .000 PTSD-Re-experiencing sub-scale 1.21 .11 .48**** .000 PTSD-Avoidance sub-scale .55 .06 .42**** .000 PTSD-Arousal sub-scale .91 .10 .42**** .000 PTSD-Dissociation sub-scale .81 .09 .42**** .000 CTD 1.50 .16 .43**** .000 CTD-Depression/Anxiety Interface Sub-scale .29 .04 .31**** .000 CTD-Suicidality sub-scale .05 .04 .07 .180 CTD-Executive Function Deficits Sub-scale .28 .03 .39**** .000 CTD-Dissociation/Psychosis Sub-scale .46 .05 .43**** .000 (a) Findings are obtained after the effects of gender, age, marital status; education and income were controlled statistically; *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001, n = 399.  I. A. KIRA ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 97 Table 5. The direct and indirect effects of cumulative Negative Appraisal of Trauma on AA, MHS and Poor health. Endogenous Variables Causal Variables AA Health MHS CTD PTSD depression Anxiety Cumulative Negative appraisal Direct Effects .474* .000 .303** .000 .000 .000 .000 Indirect Effects .000 .057** .179** .365** .400** .346** .339*** Total Effects .474* .057** .482** .365** .400** .346** .339*** Annihilation Anxiety Direct Effects .000 .119** .338** .000 .000 .000 .000 Indirect Effects .000 .000 .039** .286** .313** .271** .265** Total Effects .000 .119** .377** .286** .313** .271** .265** General Health Direct Effects .000 .000 .330* .000 .000 .000 .000 Indirect Effects .000 .000 .000 .250* .274* .237* .232* Total Effects .000 .000 .330* .250* .274* .237* .232* Mental Health Syndrome Direct Effects .000 .000 .000 .758** .831** .718** .703** Indirect Effects .000 .000 .000 .000 .000 .000 .000 Total Effects .000 .000 .000 .758** .831** .718** .703** Squared Multiple Correlations .225 .014 .450 .574 .691 .516 .494 AA = Annihilation Anxiety, MHS = Mental Health Syndrome, CTD = Cumulative Trauma Disorders; + p < .10 (close to significant) *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001, ****p < .0001. Figure 1. Path diagram for annihilation anxiety as a mediator of the effects of cumulative identity trauma on poor physical and mental health.  I. A. KIRA ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 98 Table 6. The direct and indirect effects of collective Identity Trauma on AA and MHS. Endogenous Variables Causal Variables AA Health MHS CTD PTSD depression Anxiety Collective Identity Negative appraisal Direct Effects .869** .000 .363** .000 .000 .000 .000 Indirect Effects .000 .104** .180* .411** .454** .386** .379** Total Effects .869** .104** .543** .411** .454** .386** .379** Annihilation Anxiety Direct Effects .000 .119** .169+ .000 .000 .000 .000 Indirect Effects .000 .000 .038** .157* .173* .147* .145* Total Effects .000 .119** .207** .157* .173* .147* .145* General Health Direct Effects .000 .000 .322* .000 .000 .000 .000 Indirect Effects .000 .000 .000 .244* .270* .229* .225* Total Effects .000 .000 .322* .244* .270* .229* .225* Mental Health Syndrome Direct Effects .000 .000 .000 .757** .837** .710** .698** Indirect Effects .000 .000 .000 .000 .000 .000 .000 Total Effects .000 .000 .000 .757** .837** .710** .698** Squared Multiple Correlations .754 .014 .408 .574 .700 .504 .488 AA = Annihilation Anxiety, MHS = Mental Health Syndrome, CTD = Cumulative Trauma Disorders; + p < .10 (close to significant) *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001, ****p < .0001. negative appraisal has more predictive power in this adult population. AA in its turn predicted poor physical and mental health in this population. Further, AA was found to have sig- nificant indirect effects on suicidality. Dissociation, anxiety and depression comorbidity, PTSD-emotional numbness/ dissocia- tion were the most significant mediators of the indirect effects of AA on suicidality. The findings emphasize the strong direct effects of AA on re-experiencing, general anxiety and dissocia- tion/psychosis respectively. Re-experiencing or the re-emer- gence of catastrophic memories had been long seen in the psy- choanalytic literature as the source of the emergence of delu- sional system and dissociation as defense mechanisms that protect against such re-emergence (e.g., Segal, 1977). Results of path analysis generally confirmed that AA and general anxi- ety mediated the effects of cumulative traumas and specific trauma types, especially collective identity, attachment and secondary trauma, on mental health. Further, the findings high- light the importance of assessing for the presence of AA in therapy as one of the potential keys of healing and of stopping its catastrophic effects on emotional and physical suffering, as well as suicidality of the patient. While the findings demonstrated the benefits of integrating the psychoanalytic and cognitive appraisal theories in evaluat- ing the clinical utility of the AA, they introduced this short measure that can be a useful short clinical assessment tool as well as a valid, reliable measure in research with traumatized populations. The measure was subsequently utilized in research on Pales- tinian adolescents and proved to have good psychometric prop- erties in this population. It has alpha = .87, and significantly predicted collective identity commitment, depression, suicide, militancy and fear of death (Kira, et al., 2011b). REFERENCES Arbuckle, J. L. (2006). A m o s 7.0 user’s guide. Chicago: SPSS. Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York, NY: Freeman. Borg, D. (2003). An investigation of the relationship between levels of formal decrement, ego functioning and annihilation anxiety in Ror- schach protocols. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The sciences and Engineering, 64, 1892. Cassidy-Charron, D. (2003). The relationship between stimulus recep- tivity, organizational ability and annihilation anxiety. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering, 64, 1894. Cassiman, S. A. (2005). Toward more inclusive poverty knowledge: Traumatological contributions to the poverty discourse. The Social Policy Journal, and: Cutting Edge of Social Policy Research, 4, 93- 106. Chochinov, H., Wilson, K., Enns, M., & Lander, S. (1997). “Are you depressed?” Screening for depression in the terminally ill. American  I. A. KIRA ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 99 Journal of Psychiatry, 1 5 4 , 674-676. Cialdini, R. B., Borden, R. J., Thorne, A., Walker, M. R., Freeman, S., & Sloan, L. (1976). Basking in reflected glory: Three football field studies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 34, 366-375. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.34.3.366 Erceg-Hurn, D. & Mirosevich, V. (2008). Modern robust statistical methods: An easy way to maximize the accuracy and power of your research. American P sy ch ol og is t, 63, 591-601. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.63.7.591 Garwood, A. (1996). The Holocaust and the power of powerlessness: Survivor guilt an unhealed wound. British Journal of Psychotherapy, 13, 243-258. doi:10.1111/j.1752-0118.1996.tb00880.x Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cut-off criteria for fit indexes in co- variance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alterna- tives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1-55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118 Hurvich, M. (2003). The places of annihilation anxieties in psychoana- lytic theory. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 51, 579-616. doi:10.1177/00030651030510020801 Hurvich, M. (1998). Scoring manual for the hurvich experience inven- tory. Unpublished. Kira, I. (2001). Taxonomy of trauma and trauma assessment. Trauma- tology, l-2, 1-14. Kira, I. (2002). Suicide terror and collective trauma: A collective terror management paradigm. The American Psychological Association Annual Convention, Chicago, Illinois, APA PsycNet. Kira, I. (2004a). The dynamics of identity trauma: Suicide and suicide terror. The XXVIII International Congress of Psychology, Beijing, China. Kira, I. (2004). Cumulative trauma disorder: A new scale for complex PTSD. The XXVIII International Congress of Psychology, Beijing, China. Kira, I. (2006). Collective identity terror in the Israeli-Palestinian con- flict and potential solutions. In Judy Kuriansky (Ed.), Terror in the Holy land: Inside the anguish of Israeli-Palestinian Conflict (pp. 125-130). Westport, CT: Praeger. Kira, I., Nasser, A., Abou-Median, S., Mohanesh, J., Lewandowski, L., Ramaswamy, V., Ozkan, B., & Elamia, H. (2007). Identity salience: The contribution of trauma variables, collective identity commitment CIC, and Militancy CIM to suicidality: The Palestinians Case. The American Psychological Association Annual Convention, San Fran- cisco, APA PsycNet. Kira, I., Lewandowsk, L., Templin, T., Ramaswamy, V., Ozkan, B., & Mohanesh, J. (2008a). Measuring cumulative trauma dose, types and profiles using a development-based taxonomy of Trauma. Trauma- tology, 14, 62-87. doi:10.1177/1534765608319324 Kira, I. A., Lewandowski, L., Templin, T. N., Ramaswamy, V., Chiodo, L. M., Ozkan, B., & Mohanesh, J. (2008b). Measuring cumulative trauma dose, types, and profiles using a development-based taxon- omy of traumas: The long version. American Psychological Associa- tion: APA PsycNET. Kira, I., Templin, T., Lewandowski, L., Ramaswamy, V., Bulent, O., Abu-Mediane, S., Mohanesh, J., & Alamia, H. (2011a). Cumulative tertiary appraisal of traumatic events across cultures: Two studies. Journal of Loss and Trauma: International Perspectives on Stress & Coping, 16, 43-66. Kira, I., Alawneh, A. N., Aboumediane, S., Mohanesh, J., Ozkan, B., & Alamia, H. (2011b). Identity Salience and Its Dynamics in Palestini- ans Adolescents. Psychology, 2, 781-791. doi:10.4236/psych.2011.28120 Koepele, K., & Teixeira, M. (2000). Annihilation anxiety: A metapsy- chological exploration of D. W. Winnicott’s the Piggle. Psycho- analysis & Psychotherapy, 17, 229-256. Lovibond, S., & Lovibond, P. (1995). Manual for the depression, anxi- ety, stress scales. Sydney: Psychology Foundation. Olsen, P. (1984). Nuclear annihilation and the mechanisms of defense. Transactional Analysis Jo ur na l , 14, 217-224. Petot, J. (1976). Anxiety and existence. Perspectives Psychiatriques, 56, 97-109. MacCallum, R. C., & Austin, J. T. (2000). Applications of structural equation modeling in psychological research. Annual Review of Psy- chology, 51, 201-226. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.51.1.201 Mackie, D., Devos, T., & Smith, E. (2002). Intergroup emotions: Ex- plaining offensive action tendencies in an Intergroup context. Jour- nal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, 602-616. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.79.4.602 Miller, D. (2001). Posttraumatic stress disorder, annihilation anxiety, and psychosocial development: Dynamics and interplay. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The sciences and Engineering, 61, 3853. Mulrow, C. D., Williams, J. W., Gerety, M. B., Ramirez, G., Montiel, O. M., & Kerber, K. (1995). Case-finding instruments for depression in primary care settings. Annals of Internal Medicine, 1 22 , 913-921. Norman, J. (1994). Feelings of annihilation in closeness and to be lost at a distance: Psychoanalysis with a 5-year-old boy and his insoluble dilemma. Scandinavian Psychoanalytic Review, 17, 1-26. Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Meas- urement, 1, 385-401. doi:10.1177/014662167700100306 Segal, H. (1972). A delusional system as a defense against the re- emergence of a catastrophic situation. International Journal of Psy- choanalysis, 53, 393-401. Smith, E. R. (1999). Affective and cognitive implications of a group becoming part of the self: New models of prejudice and of the self- concept. In D. Abrams, & M. A. Hogg (Eds.), Social identity and so- cial cognition (pp. 183-196). Oxford, England: Basil Blackwell. Teixeira, M. (1984). Annihilation anxiety in schizophrenia: Metaphor or dynamic? Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 12, 377-381. doi:10.1037/h0086100 Turner, J. C. (1985). Social categorization and the self-concept: A social-cognitive theory of group behavior. In E. J. Lawler (Ed.), Ad- vances in group processes: Theory and research (Vol. 2, pp. 77-122). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. Wanous, J. & Hudy, M. J. (2001). Single-item reliability: A replication and extension. Organizational Research Methods, 4, 361-375. doi:10.1177/109442810144003

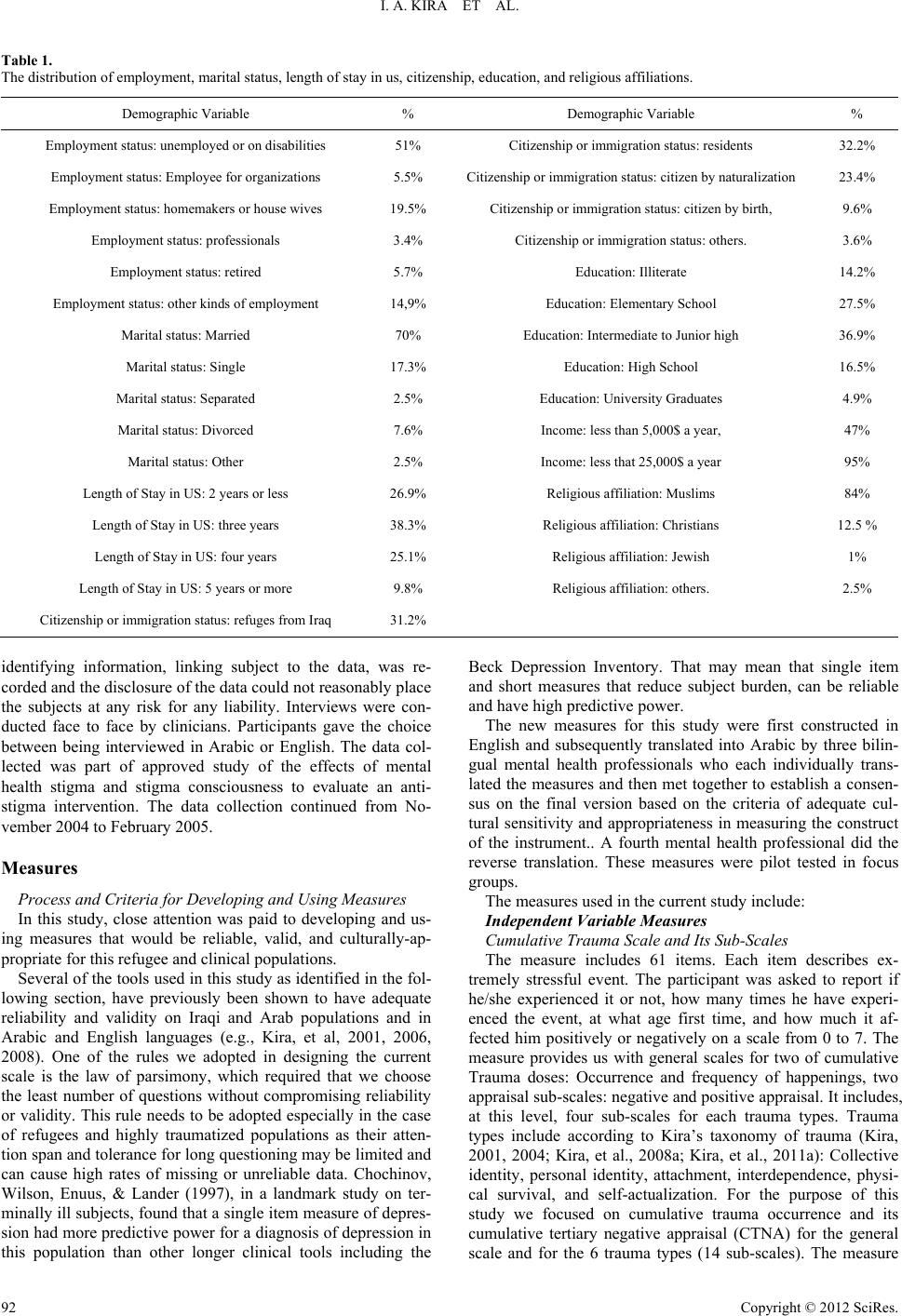

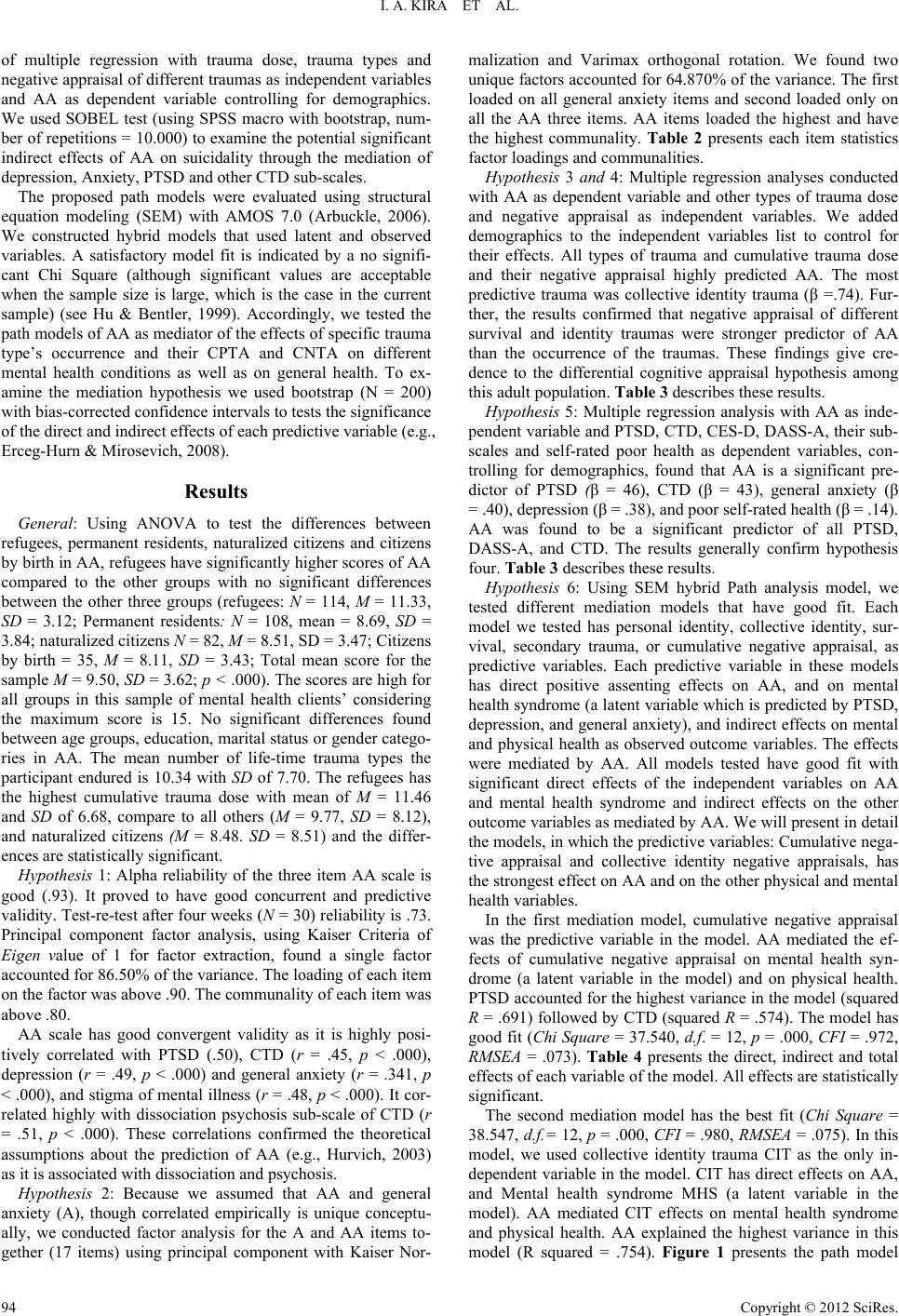

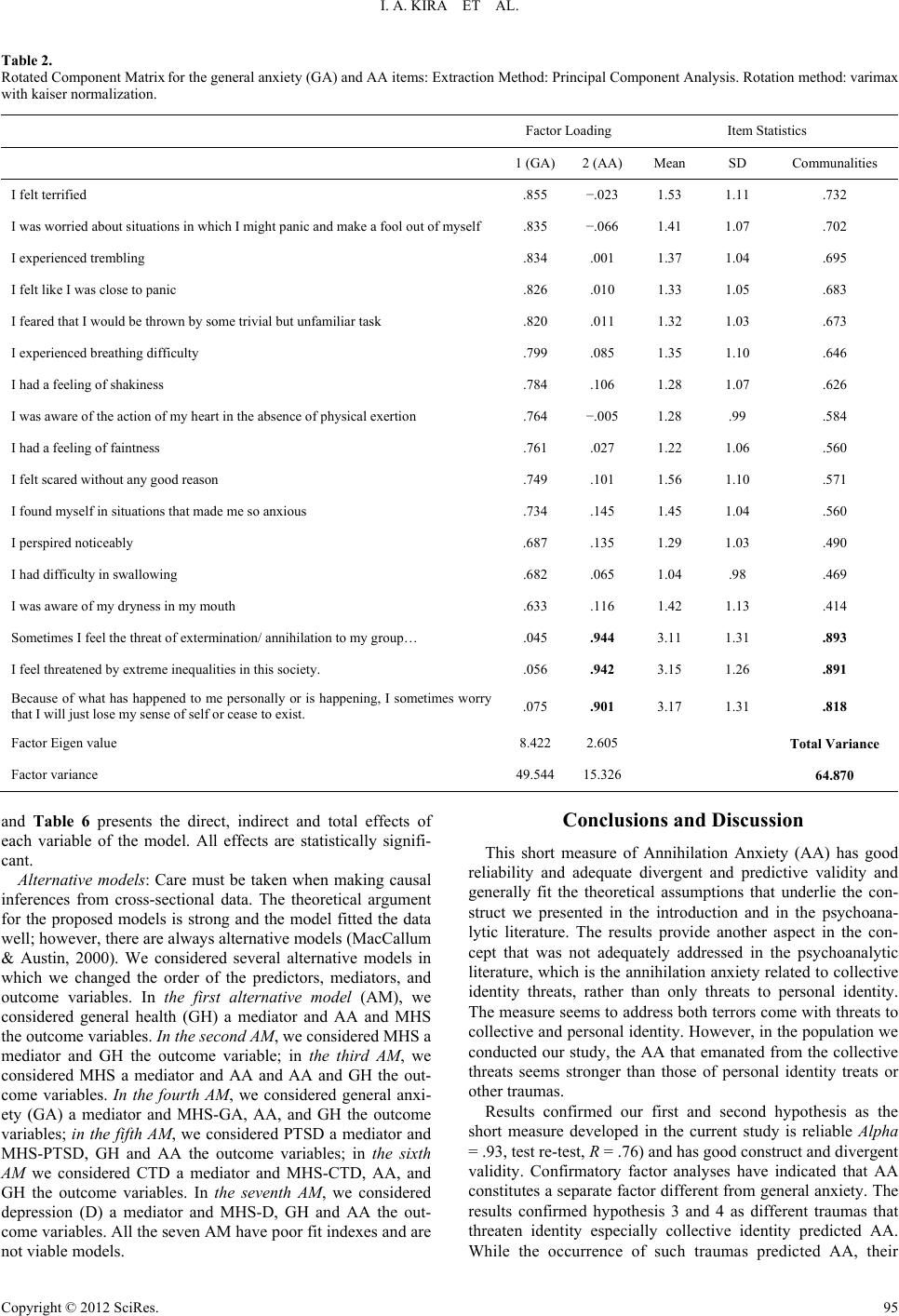

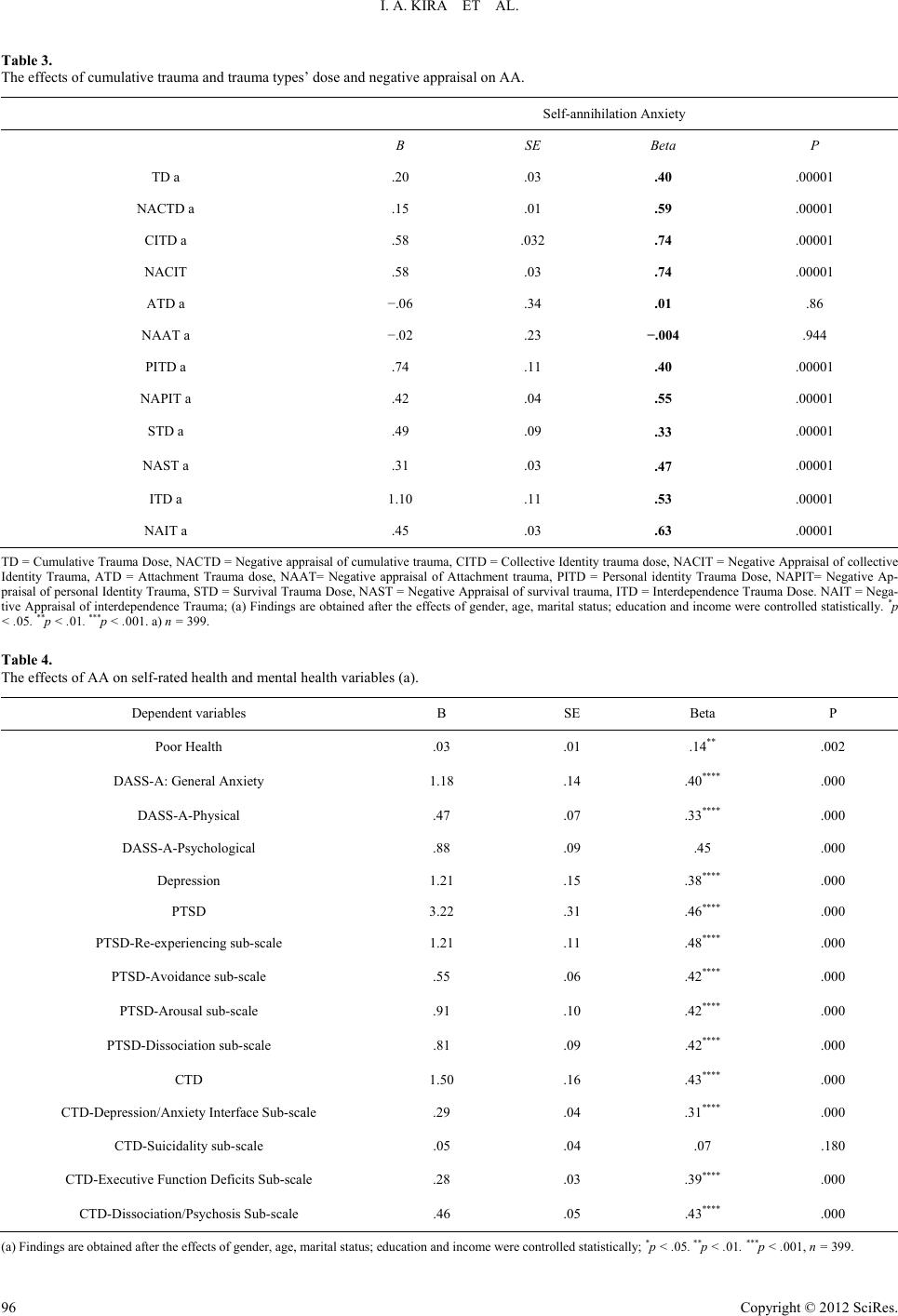

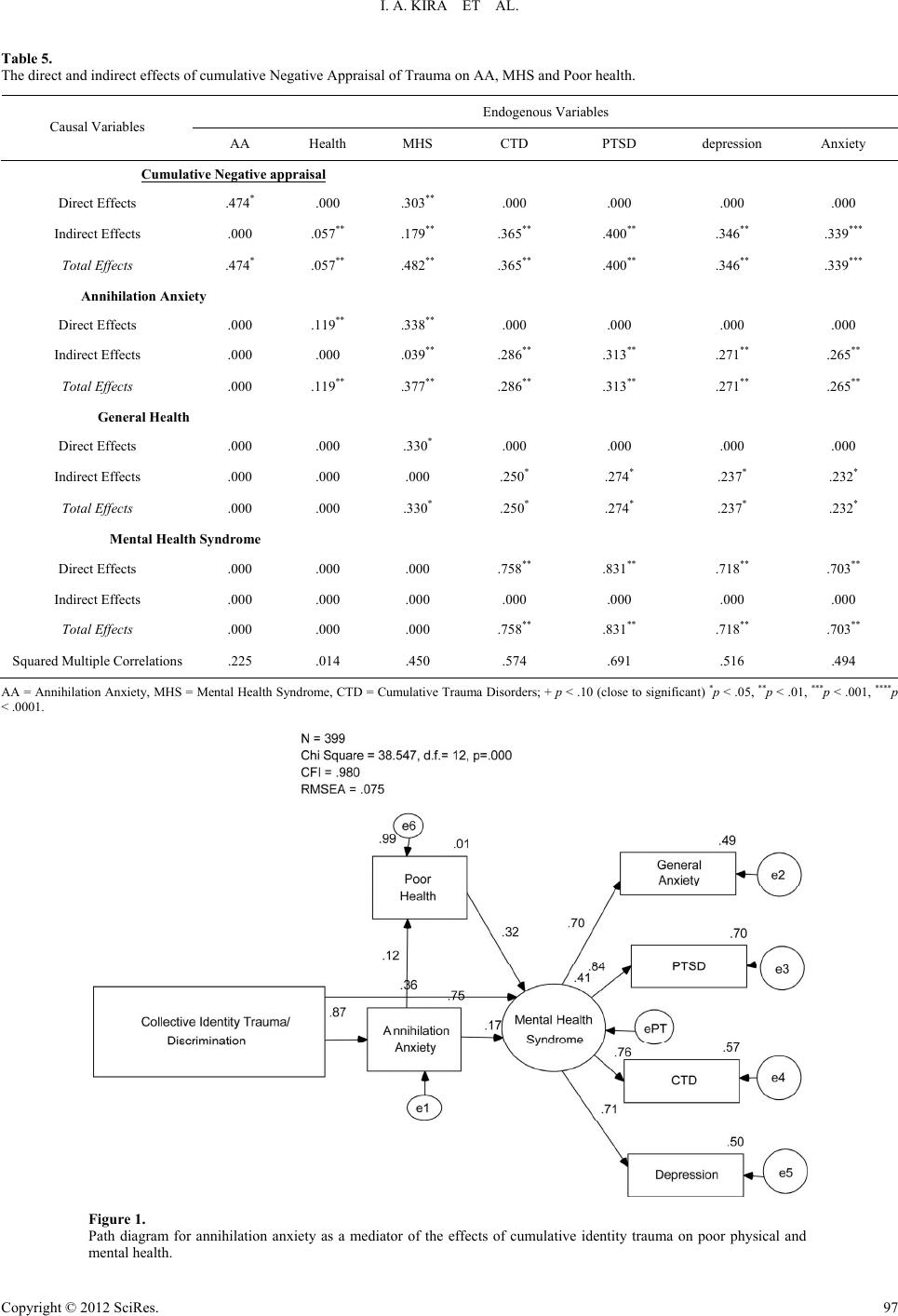

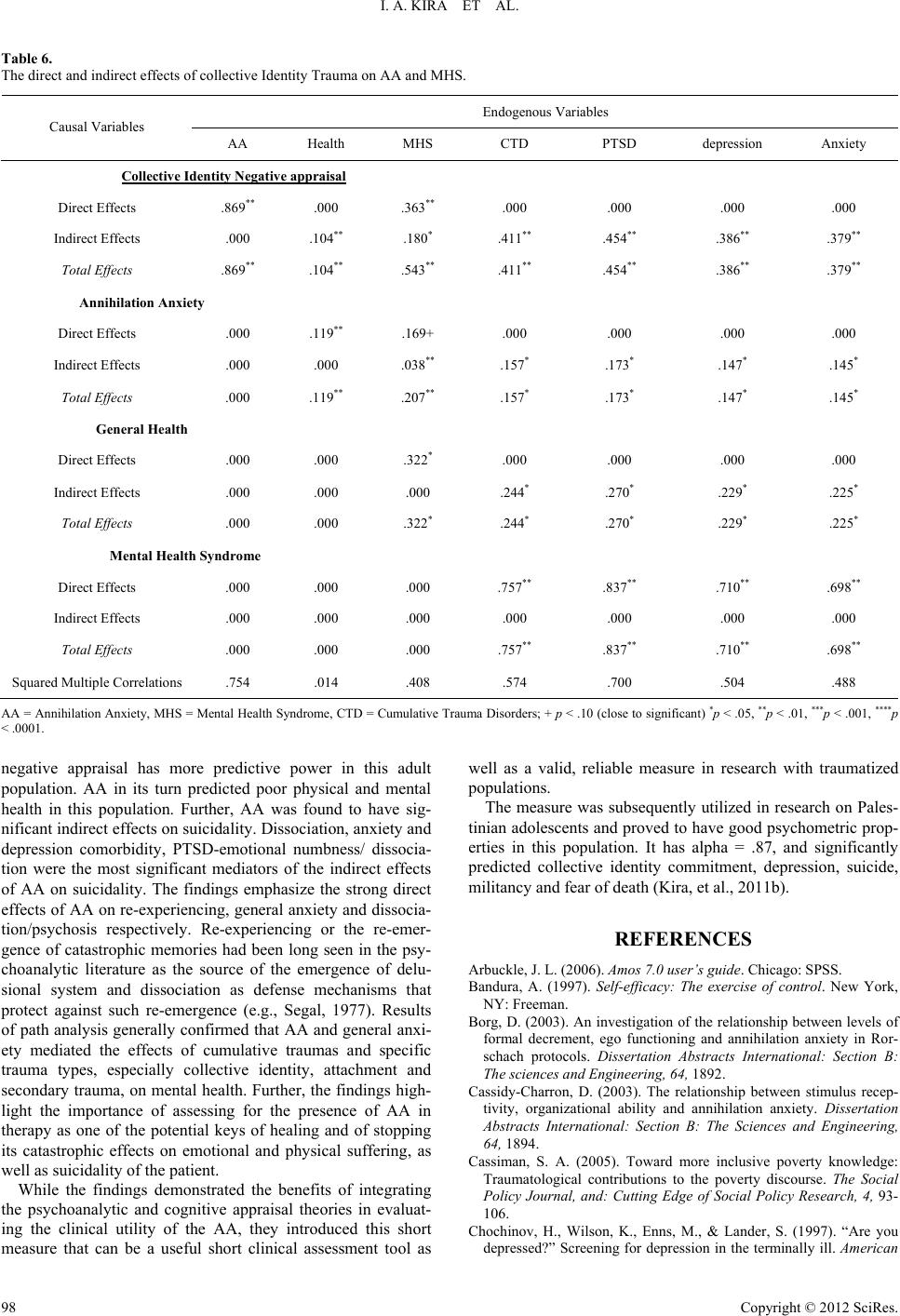

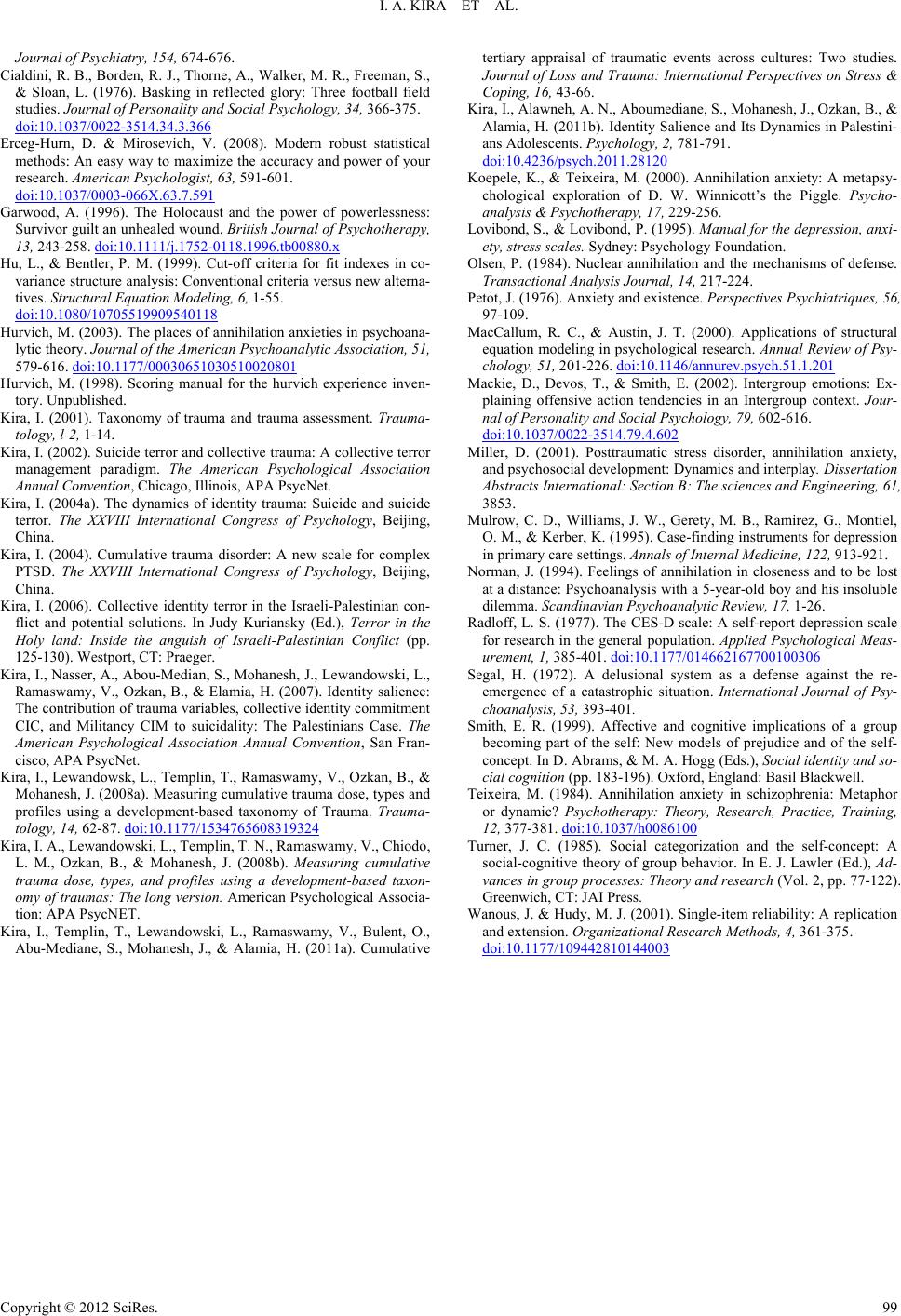

|