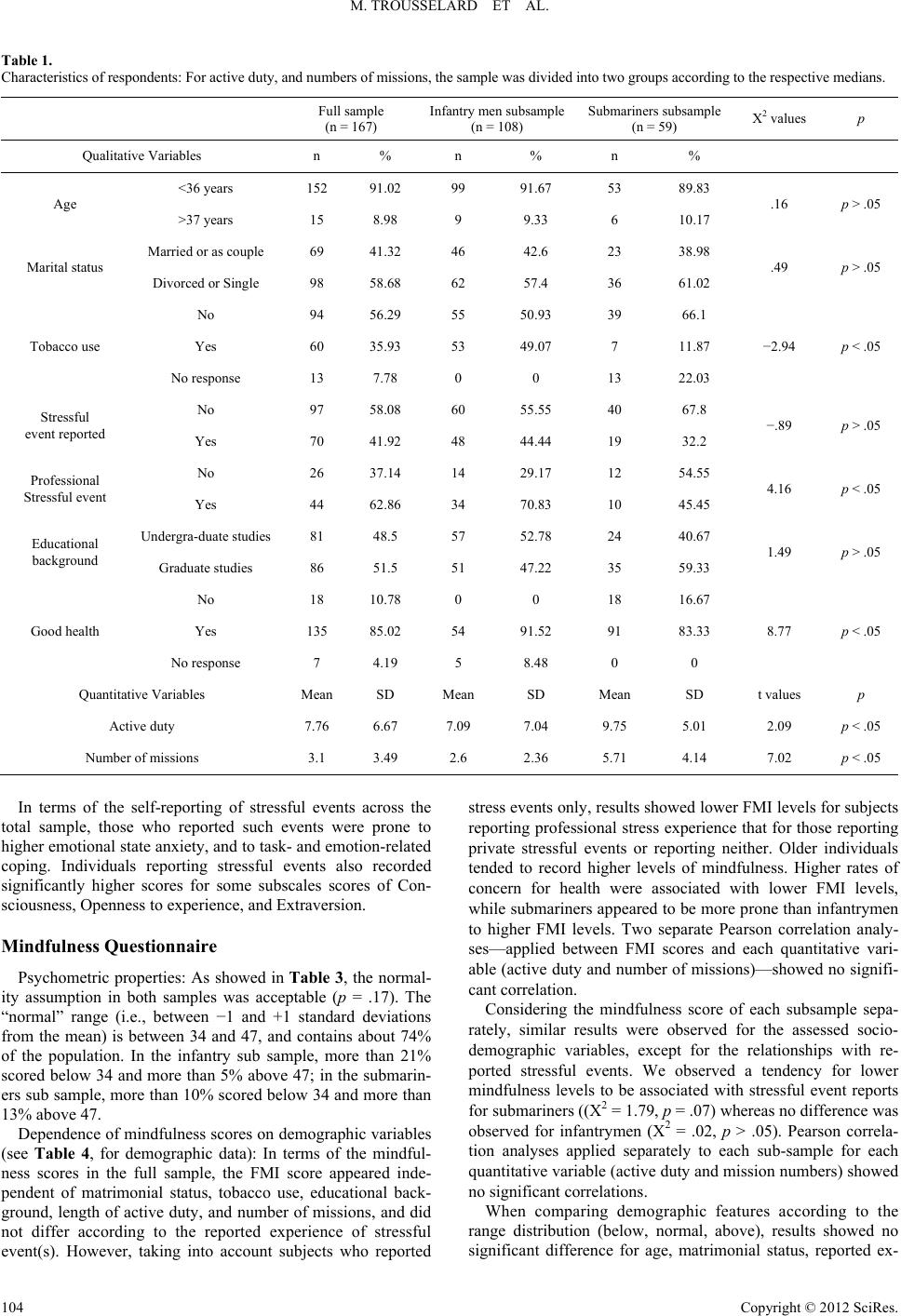

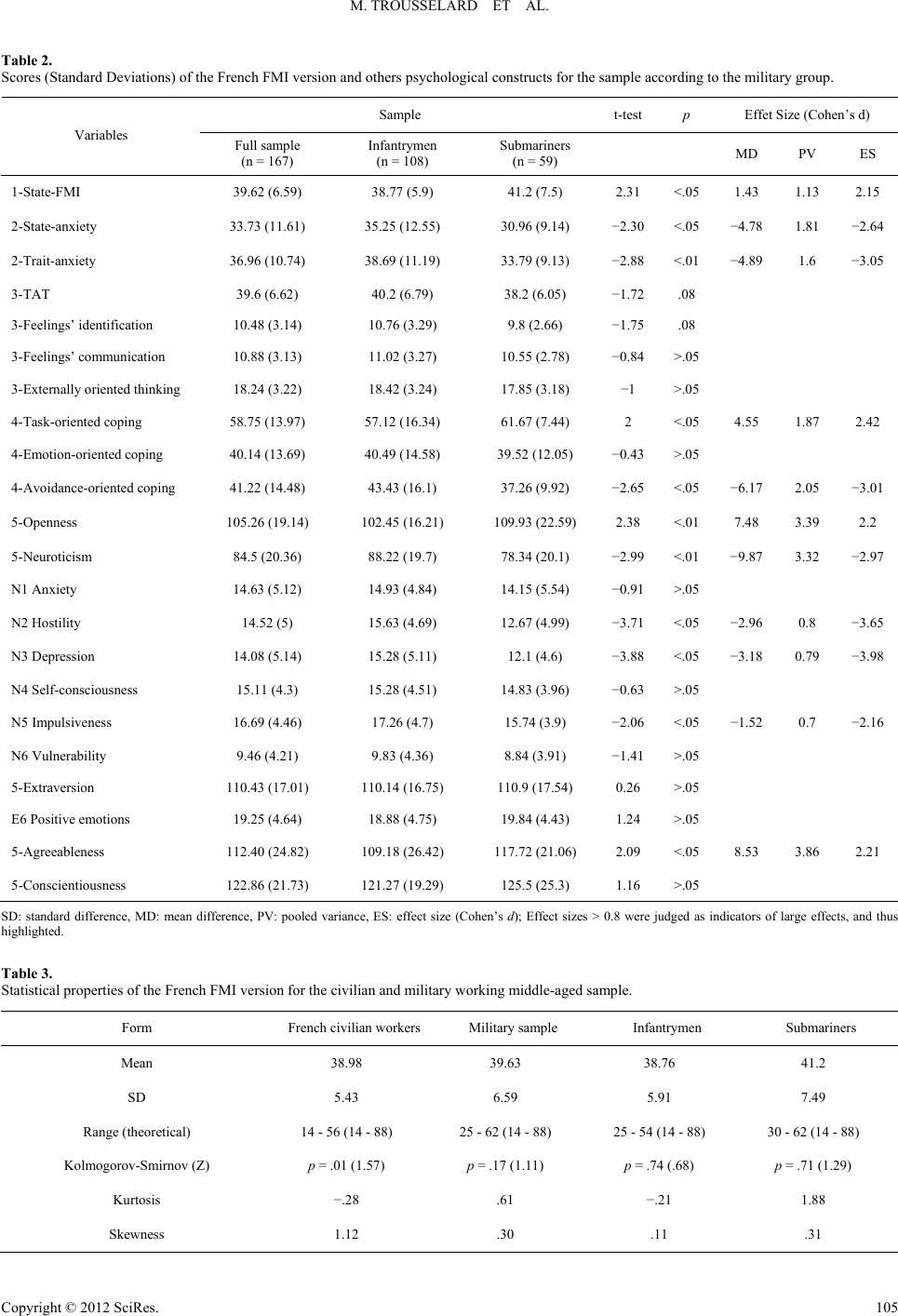

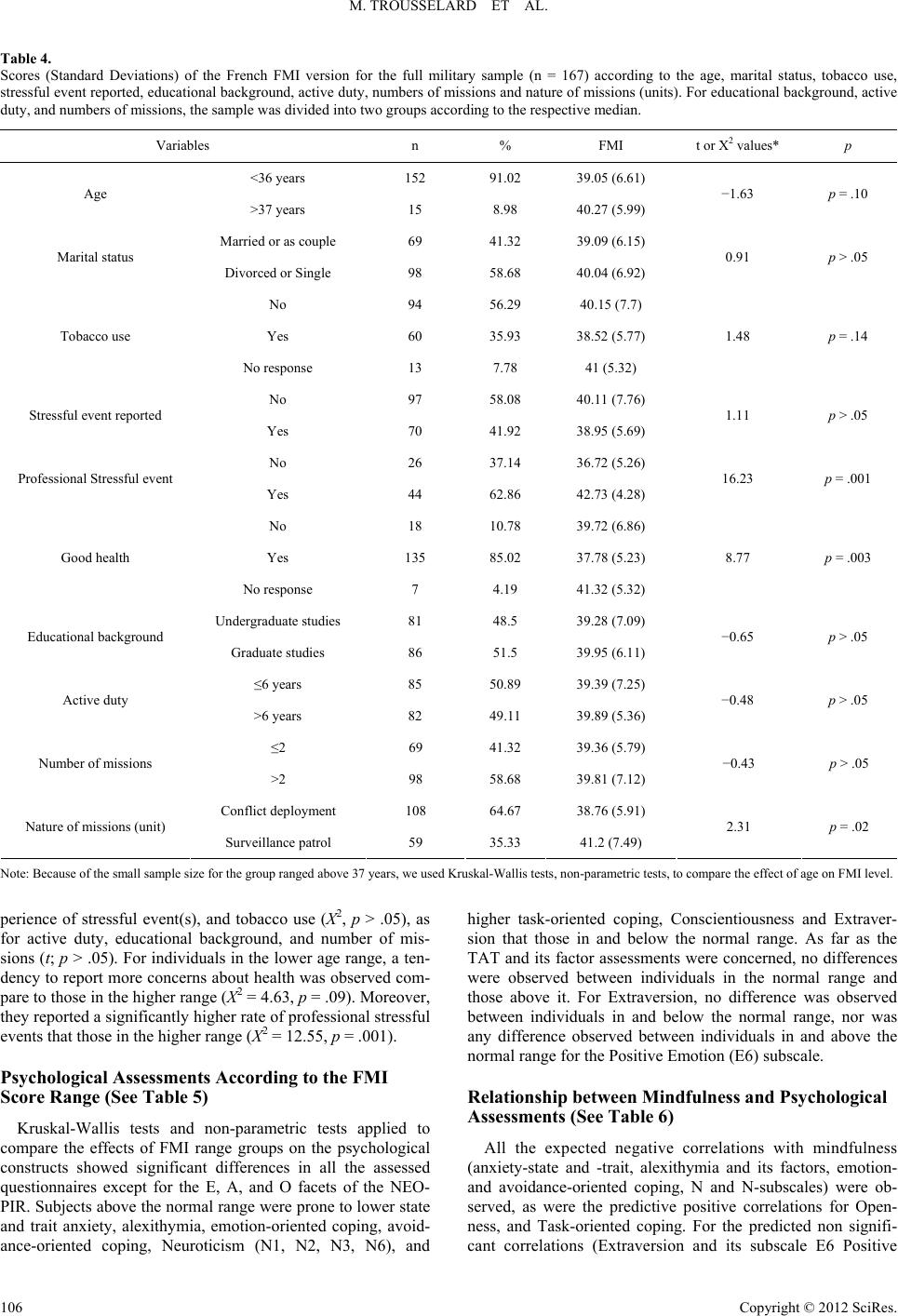

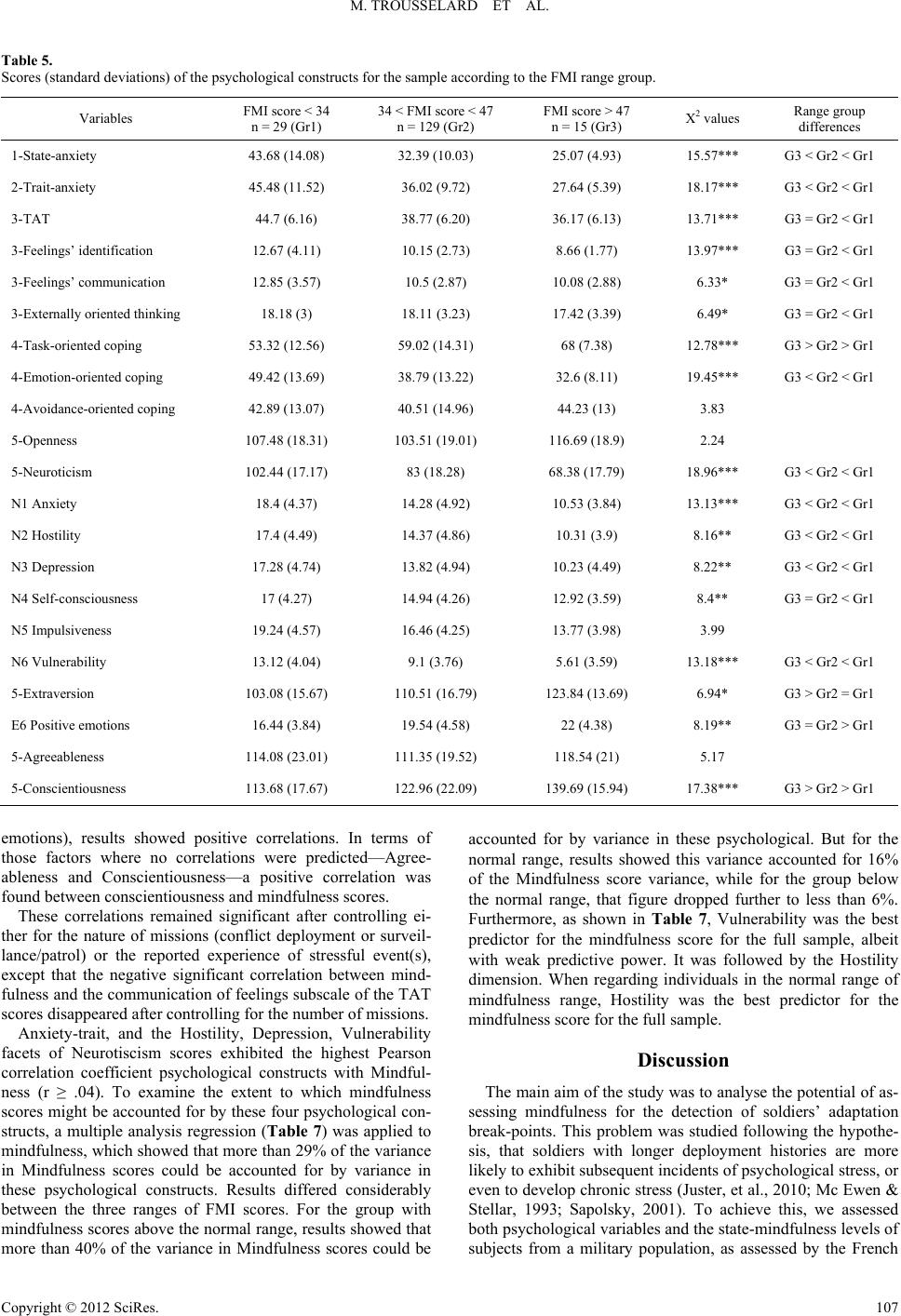

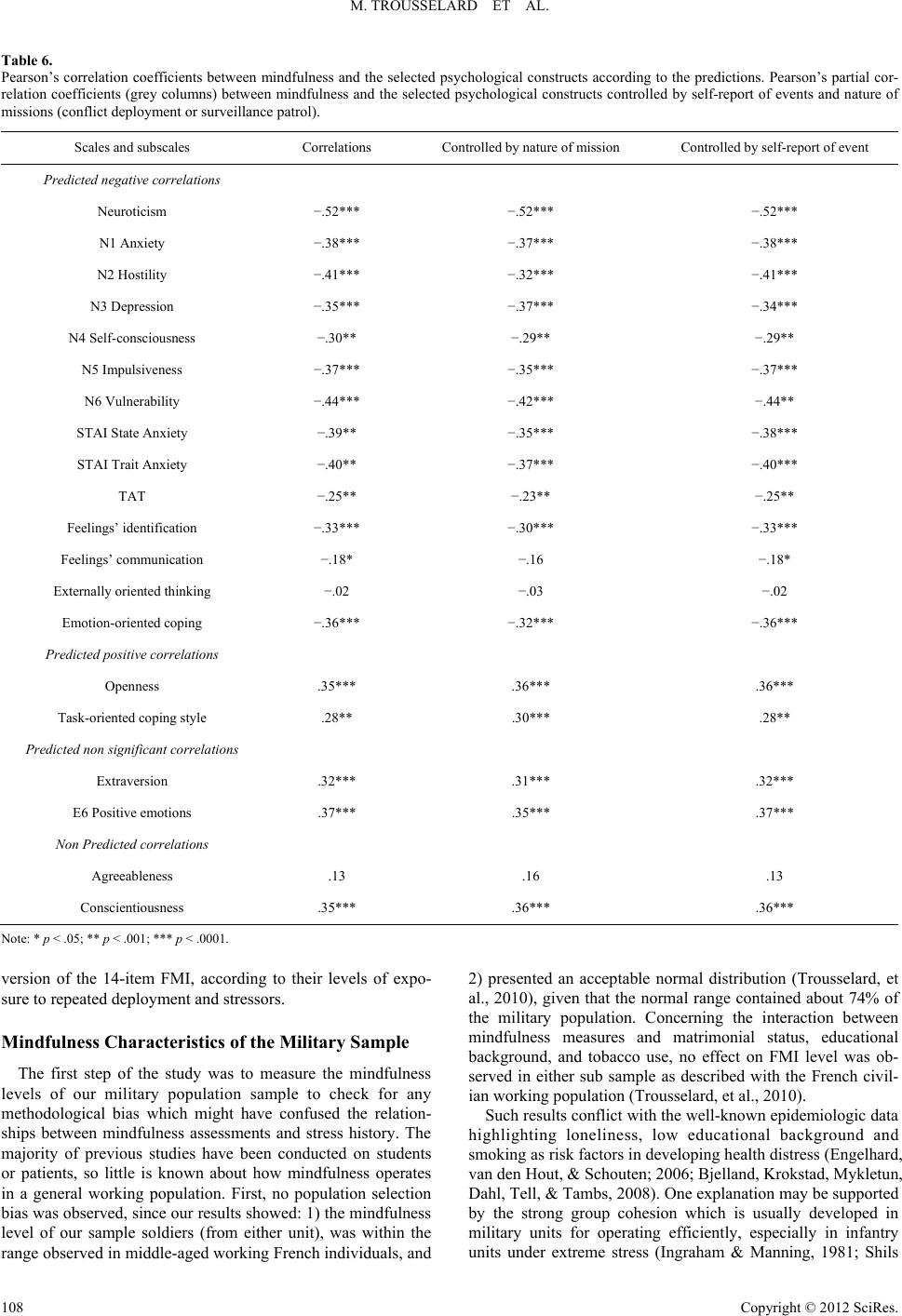

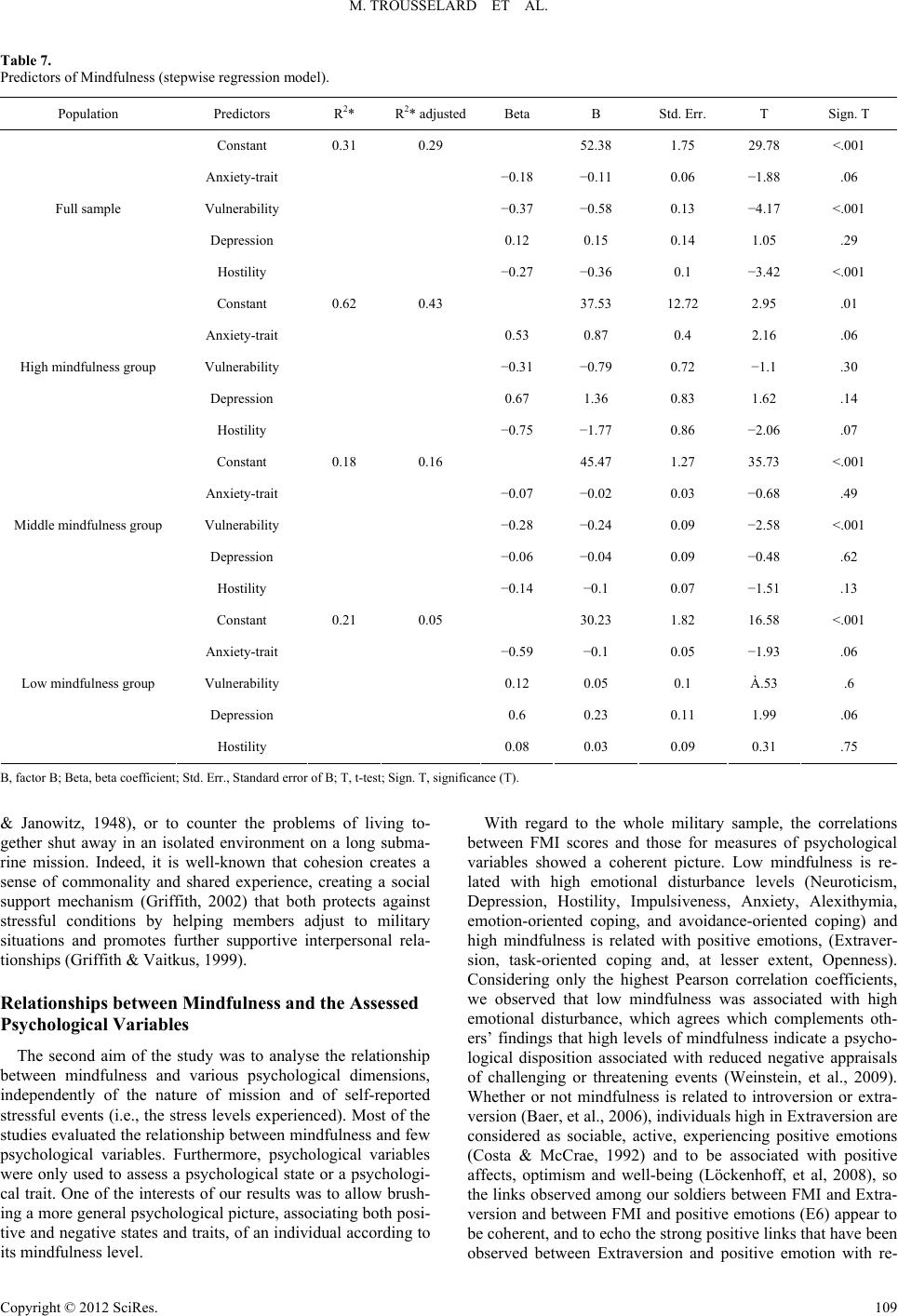

Psychology 2012. Vol.3, No.1, 100-115 Published Online January 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/psych) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/psych.2012.31016 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 100 Relationship between Mindfulness and Psychological Adjustment in Soldiers According to Their Confrontation with Repeated Deployments and Stressors Marion Trousselard1*, Dominique Steiler2, Damien Claverie1, Frédéric Canini1 1Département des Facteurs Humains, Institut de Recherches Biomédicales des Armées, La Tronche, France 2Département Management et Comportements, Grenoble Ecole de Management, Grenoble, France Email: *marion.trousselard@gmail.com Received October 9th, 2011; revised November 11th, 2011; accepted December 16th, 2011 Although interest in incorporating mindfulness into medical interventions is growing, data on the rela- tionships between mindfulness, stress and coping in military personnel is still scarce. This report investi- gates the relationship between psychological adjustment and mindfulness in soldiers according to their repeated deployments and confrontations with stressors. Our findings indicate that soldiers’ mindfulness levels were in the range of the middle-aged civilian working population, and were negatively correlated with emotional disturbance measures, and positively correlated with their subjective assessments of their own well-being. Individuals confronted with conflict deployments and stressors recorded lower mindful- ness scores, and appeared high in emotional disturbance measures. Keywords: Coping; Mindfulness; Personality; Stress Introduction Repeated deployments in unsecure places and exposure to war-related stressors lead increasing numbers of soldiers to experience stress-related symptoms—either acute such as Acute Stress Disorder (ASD) or chronic such as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)—and other mental disturbances which affect their moods, thoughts and behaviours. In fact, history has con- sistently shown that exposure to combat environments can im- pair the mental health of everyone in these environments (Red Cross), as well as negatively impacting moral engagement processes, leading to possible violations of international law. Anxiety symptoms are the most frequently reported in such circumstances and environments, but the rates of depression, addiction, suicide, alexithymia (or emotional numbing) are also high (Ginzburg, Ein-Dor, & Solomon, 2010). Studies using psychological constructs have clearly shown relationships be- tween combat exposure (duration and/or severity) and psycho- logical casualties (Juster, McEwen, & Lupien, 2010, Sapolsky, 2001). Current literature on the effects of chronic stress in gen- eral health converges around the concept of allostatic load (AL), and the AL model expands the stress-disease literature by pro- posing a temporal cascade of multi-systemic physiological dysregulations that contribute to disease trajectories. AL refers to the cumulative wear and tear on body systems caused by too much stress and/or inefficient management of the systems that promote adaptation through allostasis. AL offers important clues as to why individuals who have previously adapted suc- cessfully to repeated stressors suddenly can succumb to psy- chological distress and maladjusted behaviours (Mc Ewen & Stellar, 1993). However, the relationship among observed elements of psy- chological distress is not yet understood (Berthoz, Consoli, perez-Diaz, & Jouvent, 1999; Endler & Kocovski, 2001; Miko- lajczak & Luminet, 2006). A pertinent example concerns alexithymia, a clinically derived concept that refers to a cogni- tive-affective disorder characterized by having difficulty ex- periencing and expressing emotions (Taylor, 1984) which is considered as a vulnerability factor regarding mental disorders (see Corcos & Sperenza, 2003, for overviews). A high state- alexithymia level is understood as a response to anxiety or stress that serves to counter negative affectivity in the face of stressors (Hendryx, Haviland, & Shaw, 1991, Mikolajczak & Luminet, 2006). Two main linked questions arise. The first concerns the nature of the association between alexithymia and other psychological distress, such as anxiety and depression (Berthoz, et al., 1999), psychosomatic disorders (Porcelli, Leoci, Guerra, Taylor, & Bagby, 1996), and PTSD (Frewen, Lanius, Dozois, Neufeld, Pain, Hopper, Densmore, & Stevens, 2008) with controversial results. On the one hand, taking into account the relationship between alexithymia, anxiety, and depression, studies have found causal links between anxiety and depression and alexithymia, and also between depression and alexithymia (Hendryx, Haviland, Shaw, & Henry, 1994). On the other hand, Berthoz, et al. (1999) showed a tighter relationship between trait anxiety and alexithymia than between state anxiety and alexithymia, and also that controlling anxiety broke the rela- tionship between alexithymia and depression (Berthoz, et al, 1999). Some authors have argued that investigation is needed to understand this relationship, to determine whether alexithymia might be secondary to psychological disorders (i.e., a conse- quence of psychological distress), or whether it constituted a vulnerability factor towards mental disorders (and is thus a cause of psychological distress). This approach raises a second *Corresponding author.  M. TROUSSELARD ET AL. question concerning the stability of alexithymia—is it a stable personality trait (Martinez-Sanchez, Ato-Garcia, & Ortiz-Soria, 2003; Mikolajczak & Luminet, 2006) or a state-dependant phenomenon (Corcos & Speranza, 2003; Haviland, Shaw, Cumming, & MacMurray, 1988; Honkalampi, Hintikka, Saari- nen, Lehtonen, & Viinamaki, 2000)? Recent data suggest that although alexithymia level is described as having a high degree of relative stability, it increases in psychological distress (Mi- kolajczak & Luminet, 2006). This debate is not simply limited to alexithymia, but occurs in other psychological assessment areas. Even if they were stable, psychological human dimensions, types or attributes would be of little interest if they did not predict some important real life outcomes (Alport, 1961), such as disease, lifestyle or social (mal)adjustment. Furthermore, the debate about the sta- bility or instability of the conventional psychological constructs must take into account the question as to whether they should be conceived as lying on a continuum or as being divisible into two (or more) specific categories. While the “categorical” ap- proach—where a patient either does or does not have a certain disorder—is both familiar and traditional in psychiatry and helpful in communication, a growing of literature in the field of psychological constructs seems to suggest that psychological dimensions—especially anxiety, depression and alexithymia— should be conceived as lying along a continuum if the full spectrum of studied psychological variables is to be taken into account (Cox, Endler, & Swinson, 1991; Endler & Kocovski, 2001; Mikolajczak & Luminet, 2006). This quantitative ap- proach also implies the need to define agreed cut off points that can determine pertinent differences between illnesses that aligns with observed types of behaviour or distress. While it is imperative to move swiftly to understand fully the tremendous challenges involved if the psychological conse- quences of repeated deployments are to be limited, the most urgent challenge for military health services is to improve their ability to detect, before deployment, which soldiers are likely to be at risk of developing mental diseases when facing new stressors. Such a preventive strategy implies the need to be able to detect quickly soldiers who present even very slightest signs of stress-related psychological disturbances, so as to reveal any potential psychological disorders before the soldiers’ psycho- logical adaptation break-points are reached, so they can be kept away from confronting deleterious new stressors. The medical challenge implied here involves first the defining what “invisi- ble” psychological sign(s) could predict where a soldier’s psy- chological break-point might be, beyond which he risks devel- oping mental health wounds, and secondly developing a sensi- tive tool to diagnose such signs. In fact, a possible psychologi- cal tool for detecting individual intolerance to new stressors comes from the literature on human mindfulness, and can be assessed easily by questionnaire. Mindfulness is described as a non-elaborative, non judg- mental present-centred awareness in which each thought, feel- ing or sensation arising in a subject’s field of attention is ac- knowledged and accepted for what it is (Kabat-Zinn, 1990; Segal, Williams, & Teasdale, 2002; Shapiro & Schwartz, 1999). High levels of mindfulness are believed to be associated with well-being (Brown & Ryan, 2003), higher body satisfaction (Body Cathexis Scale; Secord & Jouard, 1953) and better iden- tification and description of feelings (Toronto Alexithymia Scale-20; Bagby, Parker, & Taylor, 1994; Bagby, Taylor, & Parker, 1994), while low mindfulness is associated with anxiety (Walach, Buchheld, Buttenmüller, Kleinknecht, & Schmidt, 2006), including social anxiety (Scale for Interpersonal Behav- iour; Arrindell, Sanavio, & Sica, 2002), and depression (Wa- lach, et al., 2006). Mindfulness therefore shows positive corre- lations with positive personality traits and well-being indicators, and negative correlations with neuroticism and emotional dis- turbance measures (Baer, Smith, & Allen, 2004; Brown & Ryan, 2003; Walach, et al., 2006). Strozzi-Heckler (2003) reports that the samurais of ancient Japan practiced mindfulness to reduce fear and stay focused, even in very stressful situations, so—from that psychological perspective—a state of high mindfulness is the opposite of a state of mental distress. Individuals with high mindfulness scores have also been shown as exhibiting greater ability to tolerate uncomfortable sensations (Eifert & Heffner, 2003; Levitt, Brown, Orsillo, & Barlow, 2004) and emotions (Hayes, Strosahl, & Wilson, 1999; Linehan, 1993; Segal, et al., 2002). So mindfulness appears to reduce negative appraisals (i.e., fear) of challenging or threatening events (Trousselard, Steiler, Ra- phel, Cian, Duymedjian, Claverie, & Canini, 2010). Stress ap- praisals concern the cognitive processes through which an indi- vidual evaluates events. Since “mindful” individuals view on- going events and experiences in a receptive manner, it could be suggested that a high mindful disposition alters the stress pro- ducing process by attenuating negative appraisals, which would therefore tend to protect individuals who have to cope with the psychological impact of a traumatic event (Weinstein, Brown, & Ryan, 2009). Mindfulness training has been shown to improve psycho- logical and physiological outcomes in subjects facing stressors (Davidson, 2004; Walache, et al., 2006) and even to treat vari- ous anxiety disorders (Germer, Siegel, & Fulton, 2005; Orsillo, Roemer, Lerner, & Tull, 2004). High scores in mindfulness questionnaire seem therefore related to subjects’ abilities to regulate their day-to-day behaviors and adapt to stressful events, and may therefore be a psychological feature that representing subjects’ resilience. Whether mindfulness scores would allow the detection of the slight psychological perturbations induced by previous combat exposure remains a question, but reductions in psychological stress and/or mindfulness training have proved that mindfulness is a relevant measure for indicating a decrease of mental dis- tress. However, whether a mindfulness measurement could be used to detect vulnerable soldiers a priori so as to protect them from encountering repeated stressors has yet to be examined. It is important for understanding how mindfulness deals with stress to assess this psychological dimension before a trauma (prospective design) rather than after a trauma (retrospective design). However, increasing proofs before introducing a pro- spective study is necessary as data on mindfulness in the mili- tary population are scarce. In this context, an exploratory retro- spective design first can be proposed to retrospectively assess differences between soldiers according to their distress status, as correlations between mindfulness and other psychological variables known to influence how a person deals with stress. In accordance, this study aims to observe mindfulness levels among French military personnel according the nature of their previous operational missions, namely repeated deployments in conflict situations or on patrol and surveillance activities. The first goal is to measure mindfulness levels of among a military population from the French Armed Forces, and the second is to evaluate the relationships, first between mindfulness and those Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 101  M. TROUSSELARD ET AL. psychological dimensions already known to be predictors of psychological protective dimensions (personality and coping features), and second between mindfulness and emotional dis- turbances (anxiety and alexithymia) according to the nature of stressors’ being confronted. It is supposed that mindfulness levels for soldiers are in the same range that those described in the French population (Trousselard, et al., 2010). Moreover, similar relationships must be found; that is both negative corre- lations between mindfulness and emotional disturbances scores, and positive correlations between mindfulness and protective dimensions scores. The final aim is to investigate the relation- ship between mindfulness and stress responses by taking into account individual histories of exposure to stressors, in terms of their intensity and their psychological sequels. This relationship is also examined in terms of its sensitivity to the numbers and severity of the stress situations encountered. It is postulated that the relationships between mindfulness and the assessed psy- chological dimensions are modulated by the number and the importance of the encountered stress. Method Participants and Procedure Two military units—a mountain infantry unit and a subma- rine unit—were contacted for the study, chosen because their operational missions differed (combat and stress vs. peaceful submarine patrol) but they also shared some strains in common (long durations, promiscuity, distance from family, inability to cope with family’s home problems, etc.). Individuals in each unit received a letter (supported by a covering letter from their respective headquarters) inviting them to participate in the study, which contained two types of information. First, the main aim of the study was noted as a psychological investiga- tion, conducted within the Armed Forces, based on a question- naire about mindfulness, together with guidance for the instru- ments’ completion. Second, respondents were told of the two criteria for being included in the study: 1) that they were not undergoing treatment and 2) that they had no personal interest in the concept of “mindfulness”. The set of self-report ques- tionnaires, including common socio-demographic data and five psychological measurement tools for studying the promotion of adaptability to stress, was presented online on each unit’s intranet between September and December 2009. The guide- lines for internet-based experimenting proposed by Reips (2002) were followed to ensure data quality, and answers were coded to ensure confidentiality. Volunteers—who had all given writ- ten informed consent before participation—completed the questionnaires (anonymously) online and at a single session. After excluding incomplete sets of answers, our final sample consisted of 167 French servicemen soldiers—108 infantrymen and 59 submariners. The study was conducted in accordance with all applicable regulatory requirements, including the 1996 version of the Helsinki Declaration, and approved by the French Military Health Service’s ethics committee. Measures The socio-demographic data collected included age, ethnicity, gender, educational level, matrimonial status, duty service, usual activities, rank and number of deployments. Duration of mission was not required. Age data was requested in the three divisions (under 21; 22 - 36; over 36), while educational level data was also requested in two categories - undergraduate level (one or two years at military school) and graduate level (two to five years of more specialized technical courses). Subjects were also questioned about whether they had experienced stressful events in the last two years in their private or professional lives (respondents were only asked to answer Yes or No, to indicate whether the stressful events mainly concerned their private or professional lives, and to indicate the total number of events where their response was positive) and about whether or not they had concerns about their health (again, only on a Yes/No basis). Respondents’ mindfulness levels were assessed using the French version of the Freiburg Mindfulness Inventory-14 (FMI), which is a short form with 14 items developed for people with no background knowledge about mindfulness (Trousselard, et al., 2010; Walach, et al., 2006). It constitutes a consistent and reliable scale evaluating several important aspects of mindful- ness (internal consistency of the scale based on the one-factor solution was .74, and test-retest reliability was good with an intra-class correlation coefficient of .80 (p < .01); Trousselard, et al., 2010). It is considered as one-dimensional for practical purposes (Kohls, Sauer, & Walach, 2009; Walach, et al., 2006). Each item is evaluated on a four-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree) and, depending on the suggested time frame, can be used to assess state- or trait-like components. For the purposes of this study, this short form was used for measuring respondents’ state of mindfulness. The personality assessments were conducted by means of the French (Rolland, 1998) version of the NEO Personality Inven- tory-Revised (NEO-PIR; Costa & McCrae, 1992). This ques- tionnaire is a hierarchically structured instrument based on the Five Factor Model (FFM—Cattell, Cattell, Cattell and Kelly, 1999) measuring five personality domains—Neurotiscism (N), Extraversion (E), Openness to experience (O), Agreeableness (A) and Conscientiousness (C)—with each factor having six subscales for individual facets. Individuals who score high on Neuroticism are more likely than average to experience feelings such as anxiety, anger, guilt and depressed moods, and neuroti- cism scales were expected to have negative correlations with mindfulness scores (Brown & Ryan, 2003). Individuals with high Extraversion scores are considered as sociable, active and more likely to experience positive emotions (Costa & McCrae, 1992), and the association between extraversion and positive attitudes, optimism, and well-being (Löckenhoff, Sutin, Ferruci, & Costa, 2008) means it has been predicted to be positively linked with mindfulness (Baer, Smith, Hopkins, Krietemeyer, Toney, et al., 2006; Brown & Ryan, 2003). Openness to ex- perience includes receptivity to novel experiences, actions, and greater than average interest in imaginative and reflective thought, so this scale was expected to be positively correlated with mindfulness scores (Brown & Ryan, 2003). In contrast to the three domains, studies on the psychological implications of Agreeableness and Conscientiousness are rather scarce. Agree- ableness primarily describes interpersonal tendencies: agreeable individuals are more likely able to gain social support (Hoth, Christensen, Ehlers, Raichle, & Lawton, 2007), but this proso- cial orientation has not led researchers to predict any significant correlation with mindfulness. Conscientiousness has been asso- ciated with better objective and subjective health, greater vital- ity and emotional stability (Friedman, 2000; Jerram & Coleman, 1999). Since this factor promotes individuals to act in a delib- erate fashion and to exercise self-control (Costa & McCrae, 1992), it could conflict with the acceptance of all thoughts—as Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 102  M. TROUSSELARD ET AL. characterised by mindfulness—again, therefore, scholars have not felt able to predict any correlation between conscientious- ness and mindfulness. Coping refers to the set of cognitive and behavioural strate- gies used by individuals to manage the demands of their stress- ful situations (Folkman & Moskowitz, 2004), and we analysed the construct using the French version of the Coping Inventory of Stressful Situation (CISS; Endler & Parker, 1999), a 48-item self-report questionnaire assessing three general coping styles: task-oriented, emotion-oriented and avoidance-oriented. Mind- fulness was predicted to correlate positively with task-oriented coping, which has been considered to promote effective recov- ery from many types of stressful situations (Penley, Tomaka, & Wiebe, 2002; Zeidner & Saklofske, 1996), while task oriented strategies have been shown to promote mindfulness training (Baer, et al., 2006, Dobkin, 2008). Conversely, mindfulness was predicted to correlate negatively with emotion-oriented coping, since mindfulness training seems to decrease the use of emotional coping strategies (Baer, et al., 2006, Dobkin, 2008). Anxiety was checked using the French version of the Spiel- berger State-Trait-Anxiety Inventory (S-STAI; Spielberger, 1972), a 40-item self-reporting questionnaire divided into 2 subscales. 20 items on the state subscale ask subjects to report the extent of their anxiety at particular moments, while the remaining 20 (on the trait subscale) ask respondents to indicate the intensity of their anxiety in general: both scores were com- puted in this study. Since mindfulness levels correlate nega- tively with the anxiety subscale of the 9-item Profile of Mood states (POMS; McNair, Lorr, & droppleman, 1971), the state S-STAI level (Brown & Ryan, 2003), and Neuroticism (Baer, et al., 2006), we predicted negative correlations between mind- fulness scores and both state and trait anxiety scores. Alexithymia was assessed using the French version of the Toronto Alexithymia Scale-20, a 20-item self-reporting ques- tionnaire (TAS-20, Bagby, et al., 1994) developed from the original 26-item self-reporting scale (Taylor, Ryan, & Bagby, 1985) which is considered as the standard self-report instrument for studying three factors that correspond to three of the four theoretical dimensions of the alexithymia construct (Taylor, et al., 1985). The first dimension reflects the ability to identify and describe feelings, and to distinguish between feelings and bodily sensations, the second reflects the ability to communi- cate feelings to other people, while the third deals with exter- nally oriented thinking. (The fourth factor—daydreaming—is not assessed in the 20-item form.) Both the total score and those of three individual subscales were computed in this study. The overall alexithymia score was predicted to correlate nega- tively with mindfulness, as has been previously reported (Baer, et al., 2006; Brown & Ryan, 2003; Walach, et al., 2006). In terms of the individual dimensions, negative correlations were also expected between the first two and mindfulness—which is described as the ability to observe and describe feelings—but we made no prediction as to its association with externally ori- ented thinking. Statistical Analysis All analyses were performed using the SPSS 17.0 software package. Student’s “t”-test or chi-square were used to study inter-sample differences, and Pearson correlation coefficients to analyse relationships between FMI scores and those for other psychological variables. A linear regression of the correlated psychological variables on the FMI scores was applied to pro- vide a context for interpreting the relationships between mind- fulness and the psychological constructs. Variables are expres- sed as mean (M) ± standard deviation (SD, square roots of vari- ance). The effect sizes were estimated, using Cohen’s d (Cohen, 1988). According to Cohen (1988), values above .80 were taken to indicate large effects and .50 - .80 as moderate effects. Results Socio-Demographic Sample (See Table 1) The descriptive findings for the full sample of 167 respon- dents showed that more than 98% were men, 91.02% were between 18 and 36 years (11.37% between 18 and 21, 79.64% between 21 and 36) and 8.98% were between 37 and 55 . They were predominantly Caucasian (>75%), 41.31% were married or living as couples and 35.93% were smokers. They had served 7.76 ± 6.67 years on active duty. The mean (standard deviation) number of missions was 3.1 (M = 3.49) ranging from 0 to 15. As might be expected, length of active duty was posi- tively correlated the number of missions (r = .55; p < .01). Of the sample population, 108 (64.7%) were from the moun- tain infantry unit (sub sample 1) and the remaining 59 (35.3%) served as submariners (sub sample 2). More than 98% of the mountain infantrymen were men, and all had been engaged in more than two operational deployments (2.6 ± 2.36). More than 44% (n = 48) reported experience of a recent stressful event in last years, experiencing a stressful event in recent years, and more than 16% reported health concerns. All the submariners were men, and all had engaged in more than five submarine patrols (5.71 ± 4.14). More than 32% (n = 19) reported experi- ence of a recent stressful event, but none reported being con- cerned about their health. No significant differences were ob- served in terms of educational background, age or matrimonial status between the two sub samples, although infantrymen smoked more than submariners. The positive correlation be- tween length of active duty and the number of missions held in both samples (r = .72; p < .01 and r = .51; p < .01 for subma- riners and infantrymen respectively). Infantrymen reported fewer years of active service, and significantly fewer numbers of missions than submariners. They also reported a higher rate of health concerns, and a lower total number of stressful events, but a higher number of professional stressful events. In terms of the nature of the stressful events respondents reported for each sample separately, our results showed that submariners report- ing slightly more private than professional stressful events (47.5% to 46.3%; with 6.1% making no response) whereas the great majority of stressful events reported by infantrymen were professional (83.4% against 12.4%, with 4.2% no responses). Psychological Assessments According to the Sub Samples (See Table 2) Comparing the two sub samples, significant differences were observed for state- and trait-anxiety, for task- and avoidance- oriented coping subscales, and for Neuroticism, Agreeableness, and Openness to experience scales and subscales scores. The mountain infantrymen recorded lower mindfulness scores, higher state- and trait-anxiety scores, lower task-oriented cop- ing scores, higher avoidance-oriented coping scores, higher Neuroticism scores, lower Agreeableness scores, and lower Openness to experience scores. All these effects are strong (d > .8) as showed in Table 2. 0 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 103  M. TROUSSELARD ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 104 Table 1. Characteristics of respondents: For active duty, and numbers of missions, the sample was divided into two groups according to the respective medians. Full sample (n = 167) Infantry men subsample (n = 108) Submariners subsample (n = 59) Χ2 values p Qualitative Variables n % n % n % <36 years 152 91.02 99 91.67 53 89.83 Age >37 years 15 8.98 9 9.33 6 10.17 .16 p > .05 Married or as couple 69 41.32 46 42.6 23 38.98 Marital status Divorced or Single 98 58.68 62 57.4 36 61.02 .49 p > .05 No 94 56.29 55 50.93 39 66.1 Yes 60 35.93 53 49.07 7 11.87 Tobacco use No response 13 7.78 0 0 13 22.03 −2.94 p < .05 No 97 58.08 60 55.55 40 67.8 Stressful event reported Yes 70 41.92 48 44.44 19 32.2 −.89 p > .05 No 26 37.14 14 29.17 12 54.55 Professional Stressful event Yes 44 62.86 34 70.83 10 45.45 4.16 p < .05 Undergra-duate studies 81 48.5 57 52.78 24 40.67 Educational background Graduate studies 86 51.5 51 47.22 35 59.33 1.49 p > .05 No 18 10.78 0 0 18 16.67 Yes 135 85.02 54 91.52 91 83.33 Good health No response 7 4.19 5 8.48 0 0 8.77 p < .05 Quantitative Variables Mean SD Mean SD Mean SD t values p Active duty 7.76 6.67 7.09 7.04 9.75 5.01 2.09 p < .05 Number of missions 3.1 3.49 2.6 2.36 5.71 4.14 7.02 p < .05 In terms of the self-reporting of stressful events across the total sample, those who reported such events were prone to higher emotional state anxiety, and to task- and emotion-related coping. Individuals reporting stressful events also recorded significantly higher scores for some subscales scores of Con- sciousness, Openness to experience, and Extraversion. Mindfulness Q u es tionnaire Psychometric properties: As showed in Table 3, the normal- ity assumption in both samples was acceptable (p = .17). The “normal” range (i.e., between −1 and +1 standard deviations from the mean) is between 34 and 47, and contains about 74% of the population. In the infantry sub sample, more than 21% scored below 34 and more than 5% above 47; in the submarin- ers sub sample, more than 10% scored below 34 and more than 13% above 47. Dependence of mindfulness scores on demographic variables (see Table 4, for demographic data): In terms of the mindful- ness scores in the full sample, the FMI score appeared inde- pendent of matrimonial status, tobacco use, educational back- ground, length of active duty, and number of missions, and did not differ according to the reported experience of stressful event(s). However, taking into account subjects who reported stress events only, results showed lower FMI levels for subjects reporting professional stress experience that for those reporting private stressful events or reporting neither. Older individuals tended to record higher levels of mindfulness. Higher rates of concern for health were associated with lower FMI levels, while submariners appeared to be more prone than infantrymen to higher FMI levels. Two separate Pearson correlation analy- ses—applied between FMI scores and each quantitative vari- able (active duty and number of missions)—showed no signifi- cant correlation. Considering the mindfulness score of each subsample sepa- rately, similar results were observed for the assessed socio- demographic variables, except for the relationships with re- ported stressful events. We observed a tendency for lower mindfulness levels to be associated with stressful event reports for submariners ((X2 = 1.79, p = .07) whereas no difference was observed for infantrymen (X2 = .02, p > .05). Pearson correla- tion analyses applied separately to each sub-sample for each quantitative variable (active duty and mission numbers) showed no significant correlations. When comparing demographic features according to the range distribution (below, normal, above), results showed no significant difference for age, mtrimonial status, reported ex- a  M. TROUSSELARD ET AL. Table 2. Scores (Standard Deviations) of the French FMI version and others psychological constructs for the sample according to the military group. Sample t-test p Effet Size (Cohen’s d) Variables Full sample (n = 167) Infantrymen (n = 108) Submariners (n = 59) MD PV ES 1-State-FMI 39.62 (6.59) 38.77 (5.9) 41.2 (7.5) 2.31 <.05 1.43 1.13 2.15 2-State-anxiety 33.73 (11.61) 35.25 (12.55) 30.96 (9.14) −2.30<.05 −4.78 1.81 −2.64 2-Trait-anxiety 36.96 (10.74) 38.69 (11.19) 33.79 (9.13) −2.88<.01 −4.89 1.6 −3.05 3-TAT 39.6 (6.62) 40.2 (6.79) 38.2 (6.05) −1.72.08 3-Feelings’ identification 10.48 (3.14) 10.76 (3.29) 9.8 (2.66) −1.75.08 3-Feelings’ communication 10.88 (3.13) 11.02 (3.27) 10.55 (2.78) −0.84>.05 3-Externally oriented thinking 18.24 (3.22) 18.42 (3.24) 17.85 (3.18) −1 >.05 4-Task-oriented coping 58.75 (13.97) 57.12 (16.34) 61.67 (7.44) 2 <.05 4.55 1.87 2.42 4-Emotion-oriented coping 40.14 (13.69) 40.49 (14.58) 39.52 (12.05) −0.43>.05 4-Avoidance-oriented coping 41.22 (14.48) 43.43 (16.1) 37.26 (9.92) −2.65<.05 −6.17 2.05 −3.01 5-Openness 105.26 (19.14) 102.45 (16.21) 109.93 (22.59) 2.38 <.01 7.48 3.39 2.2 5-Neuroticism 84.5 (20.36) 88.22 (19.7) 78.34 (20.1) −2.99<.01 −9.87 3.32 −2.97 N1 Anxiety 14.63 (5.12) 14.93 (4.84) 14.15 (5.54) −0.91>.05 N2 Hostility 14.52 (5) 15.63 (4.69) 12.67 (4.99) −3.71<.05 −2.96 0.8 −3.65 N3 Depression 14.08 (5.14) 15.28 (5.11) 12.1 (4.6) −3.88<.05 −3.18 0.79 −3.98 N4 Self-consciousness 15.11 (4.3) 15.28 (4.51) 14.83 (3.96) −0.63>.05 N5 Impulsiveness 16.69 (4.46) 17.26 (4.7) 15.74 (3.9) −2.06<.05 −1.52 0.7 −2.16 N6 Vulnerability 9.46 (4.21) 9.83 (4.36) 8.84 (3.91) −1.41>.05 5-Extraversion 110.43 (17.01) 110.14 (16.75) 110.9 (17.54) 0.26 >.05 E6 Positive emotions 19.25 (4.64) 18.88 (4.75) 19.84 (4.43) 1.24 >.05 5-Agreeableness 112.40 (24.82) 109.18 (26.42) 117.72 (21.06) 2.09 <.05 8.53 3.86 2.21 5-Conscientiousness 122.86 (21.73) 121.27 (19.29) 125.5 (25.3) 1.16 >.05 SD: standard difference, MD: mean difference, PV: pooled variance, ES: effect size (Cohen’s d); Effect sizes > 0.8 were judged as indicators of large effects, and thus highlighted. Table 3. Statistical properties of the French FMI version for the civilian and military working middle-aged sample. Form French civilian workers Military sample Infantrymen Submariners Mean 38.98 39.63 38.76 41.2 SD 5.43 6.59 5.91 7.49 Range (theoretical) 14 - 56 (14 - 88) 25 - 62 (14 - 88) 25 - 54 (14 - 88) 30 - 62 (14 - 88) Kolmogorov-Smirnov (Z) p = .01 (1.57) p = .17 (1.11) p = .74 (.68) p = .71 (1.29) Kurtosis −.28 .61 −.21 1.88 Skewness 1.12 .30 .11 .31 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 105  M. TROUSSELARD ET AL. Table 4. Scores (Standard Deviations) of the French FMI version for the full military sample (n = 167) according to the age, marital status, tobacco use, stressful event reported, educational background, active duty, numbers of missions and nature of missions (units). For educational background, active duty, and numbers of missions, the sample was divided into two groups according to the respective median. Variables n % FMI t or Χ2 values* p <36 years 152 91.02 39.05 (6.61) Age >37 years 15 8.98 40.27 (5.99) −1.63 p = .10 Married or as couple 69 41.32 39.09 (6.15) Marital status Divorced or Single 98 58.68 40.04 (6.92) 0.91 p > .05 No 94 56.29 40.15 (7.7) Yes 60 35.93 38.52 (5.77) Tobacco use No response 13 7.78 41 (5.32) 1.48 p = .14 No 97 58.08 40.11 (7.76) Stressful event reported Yes 70 41.92 38.95 (5.69) 1.11 p > .05 No 26 37.14 36.72 (5.26) Professional Stressful event Yes 44 62.86 42.73 (4.28) 16.23 p = .001 No 18 10.78 39.72 (6.86) Yes 135 85.02 37.78 (5.23) Good health No response 7 4.19 41.32 (5.32) 8.77 p = .003 Undergraduate studies 81 48.5 39.28 (7.09) Educational background Graduate studies 86 51.5 39.95 (6.11) −0.65 p > .05 ≤6 years 85 50.89 39.39 (7.25) Active duty >6 years 82 49.11 39.89 (5.36) −0.48 p > .05 ≤2 69 41.32 39.36 (5.79) Number of missions >2 98 58.68 39.81 (7.12) −0.43 p > .05 Conflict deployment 108 64.67 38.76 (5.91) Nature of missions (unit) Surveillance patrol 59 35.33 41.2 (7.49) 2.31 p = .02 Note: Because of the small sample size for the group ranged above 37 years, we used Kruskal-Wallis tests, non-parametric tests, to compare the effect of age on FMI level. perience of stressful event(s), and tobacco use (X2, p > .05), as for active duty, educational background, and number of mis- sions (t; p > .05). For individuals in the lower age range, a ten- dency to report more concerns about health was observed com- pare to those in the higher range (X2 = 4.63, p = .09). Moreover, they reported a significantly higher rate of professional stressful events that those in the higher range (X2 = 12.55, p = .001). Psychological Assessments According to the FMI Score Range (See Table 5) Kruskal-Wallis tests and non-parametric tests applied to compare the effects of FMI range groups on the psychological constructs showed significant differences in all the assessed questionnaires except for the E, A, and O facets of the NEO- PIR. Subjects above the normal range were prone to lower state and trait anxiety, alexithymia, emotion-oriented coping, avoid- ance-oriented coping, Neuroticism (N1, N2, N3, N6), and higher task-oriented coping, Conscientiousness and Extraver- sion that those in and below the normal range. As far as the TAT and its factor assessments were concerned, no differences were observed between individuals in the normal range and those above it. For Extraversion, no difference was observed between individuals in and below the normal range, nor was any difference observed between individuals in and above the normal range for the Positive Emotion (E6) subscale. Relationship between Mindfulness and Psychological Assessments (See Table 6) All the expected negative correlations with mindfulness (anxiety-state and -trait, alexithymia and its factors, emotion- and avoidance-oriented coping, N and N-subscales) were ob- served, as were the predictive positive correlations for Open- ness, and Task-oriented coping. For the predicted non signifi- cant correlations (Extraversion and its subscale E6 Positive Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 106  M. TROUSSELARD ET AL. Table 5. Scores (standard deviations) of the psychological constructs for the sample according to the FMI range group. Variables FMI score < 34 n = 29 (Gr1) 34 < FMI score < 47 n = 129 (Gr2) FMI score > 47 n = 15 (Gr3) Χ2 values Range group differences 1-State-anxiety 43.68 (14.08) 32.39 (10.03) 25.07 (4.93) 15.57*** G3 < Gr2 < Gr1 2-Trait-anxiety 45.48 (11.52) 36.02 (9.72) 27.64 (5.39) 18.17*** G3 < Gr2 < Gr1 3-TAT 44.7 (6.16) 38.77 (6.20) 36.17 (6.13) 13.71*** G3 = Gr2 < Gr1 3-Feelings’ identification 12.67 (4.11) 10.15 (2.73) 8.66 (1.77) 13.97*** G3 = Gr2 < Gr1 3-Feelings’ communication 12.85 (3.57) 10.5 (2.87) 10.08 (2.88) 6.33* G3 = Gr2 < Gr1 3-Externally oriented thinking 18.18 (3) 18.11 (3.23) 17.42 (3.39) 6.49* G3 = Gr2 < Gr1 4-Task-oriented coping 53.32 (12.56) 59.02 (14.31) 68 (7.38) 12.78*** G3 > Gr2 > Gr1 4-Emotion-oriented coping 49.42 (13.69) 38.79 (13.22) 32.6 (8.11) 19.45*** G3 < Gr2 < Gr1 4-Avoidance-oriented coping 42.89 (13.07) 40.51 (14.96) 44.23 (13) 3.83 5-Openness 107.48 (18.31) 103.51 (19.01) 116.69 (18.9) 2.24 5-Neuroticism 102.44 (17.17) 83 (18.28) 68.38 (17.79) 18.96*** G3 < Gr2 < Gr1 N1 Anxiety 18.4 (4.37) 14.28 (4.92) 10.53 (3.84) 13.13*** G3 < Gr2 < Gr1 N2 Hostility 17.4 (4.49) 14.37 (4.86) 10.31 (3.9) 8.16** G3 < Gr2 < Gr1 N3 Depression 17.28 (4.74) 13.82 (4.94) 10.23 (4.49) 8.22** G3 < Gr2 < Gr1 N4 Self-consciousness 17 (4.27) 14.94 (4.26) 12.92 (3.59) 8.4** G3 = Gr2 < Gr1 N5 Impulsiveness 19.24 (4.57) 16.46 (4.25) 13.77 (3.98) 3.99 N6 Vulnerability 13.12 (4.04) 9.1 (3.76) 5.61 (3.59) 13.18*** G3 < Gr2 < Gr1 5-Extraversion 103.08 (15.67) 110.51 (16.79) 123.84 (13.69) 6.94* G3 > Gr2 = Gr1 E6 Positive emotions 16.44 (3.84) 19.54 (4.58) 22 (4.38) 8.19** G3 = Gr2 > Gr1 5-Agreeableness 114.08 (23.01) 111.35 (19.52) 118.54 (21) 5.17 5-Conscientiousness 113.68 (17.67) 122.96 (22.09) 139.69 (15.94) 17.38*** G3 > Gr2 > Gr1 emotions), results showed positive correlations. In terms of those factors where no correlations were predicted—Agree- ableness and Conscientiousness—a positive correlation was found between conscientiousness and mindfulness scores. These correlations remained significant after controlling ei- ther for the nature of missions (conflict deployment or surveil- lance/patrol) or the reported experience of stressful event(s), except that the negative significant correlation between mind- fulness and the communication of feelings subscale of the TAT scores disappeared after controlling for the number of missions. Anxiety-trait, and the Hostility, Depression, Vulnerability facets of Neurotiscism scores exhibited the highest Pearson correlation coefficient psychological constructs with Mindful- ness (r ≥ .04). To examine the extent to which mindfulness scores might be accounted for by these four psychological con- structs, a multiple analysis regression (Table 7) was applied to mindfulness, which showed that more than 29% of the variance in Mindfulness scores could be accounted for by variance in these psychological constructs. Results differed considerably between the three ranges of FMI scores. For the group with mindfulness scores above the normal range, results showed that more than 40% of the variance in Mindfulness scores could be accounted for by variance in these psychological. But for the normal range, results showed this variance accounted for 16% of the Mindfulness score variance, while for the group below the normal range, that figure dropped further to less than 6%. Furthermore, as shown in Table 7, Vulnerability was the best predictor for the mindfulness score for the full sample, albeit with weak predictive power. It was followed by the Hostility dimension. When regarding individuals in the normal range of mindfulness range, Hostility was the best predictor for the mindfulness score for the full sample. Discussion The main aim of the study was to analyse the potential of as- sessing mindfulness for the detection of soldiers’ adaptation break-points. This problem was studied following the hypothe- sis, that soldiers with longer deployment histories are more likely to exhibit subsequent incidents of psychological stress, or even to develop chronic stress (Juster, et al., 2010; Mc Ewen & Stellar, 1993; Sapolsky, 2001). To achieve this, we assessed both psychological variables and the state-mindfulness levels of subjects from a military populatiassessed by the French on, as Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 107  M. TROUSSELARD ET AL. Table 6. Pearson’s correlation coefficients between mindfulness and the selected psychological constructs according to the predictions. Pearson’s partial cor- relation coefficients (grey columns) between mindfulness and the selected psychological constructs controlled by self-report of events and nature of missions (conflict deployment or surveillance patrol). Scales and subscales Correlations Controlled by nature of mission Controlled by self-report of event Predicted negative correlat ions Neuroticism −.52*** −.52*** −.52*** N1 Anxiety −.38*** −.37*** −.38*** N2 Hostility −.41*** −.32*** −.41*** N3 Depression −.35*** −.37*** −.34*** N4 Self-consciousness −.30** −.29** −.29** N5 Impulsiveness −.37*** −.35*** −.37*** N6 Vulnerability −.44*** −.42*** −.44** STAI State Anxiety −.39** −.35*** −.38*** STAI Trait Anxiety −.40** −.37*** −.40*** TAT −.25** −.23** −.25** Feelings’ identification −.33*** −.30*** −.33*** Feelings’ communication −.18* −.16 −.18* Externally oriented thinking −.02 −.03 −.02 Emotion-oriented coping −.36*** −.32*** −.36*** Predicted posi tive correlations Openness .35*** .36*** .36*** Task-oriented coping style .28** .30*** .28** Predicted non s ignificant cor relations Extravers ion .32*** .31*** .32*** E6 Positive emotions .37*** .35*** .37*** Non Predicted correlations Agreeablenes s .13 .16 .13 Conscientiousness .35*** .36*** .36*** Note: * p < .05; ** p < .001; *** p < .0001. version of the 14-item FMI, according to their levels of expo- sure to repeated deployment and stressors. Mindfulness Characteristics of the Military Sample The first step of the study was to measure the mindfulness levels of our military population sample to check for any methodological bias which might have confused the relation- ships between mindfulness assessments and stress history. The majority of previous studies have been conducted on students or patients, so little is known about how mindfulness operates in a general working population. First, no population selection bias was observed, since our results showed: 1) the mindfulness level of our sample soldiers (from either unit), was within the range observed in middle-aged working French individuals, and 2) presented an acceptable normal distribution (Trousselard, et al., 2010), given that the normal range contained about 74% of the military population. Concerning the interaction between mindfulness measures and matrimonial status, educational background, and tobacco use, no effect on FMI level was ob- served in either sub sample as described with the French civil- ian working population (Trousselard, et al., 2010). Such results conflict with the well-known epidemiologic data highlighting loneliness, low educational background and smoking as risk factors in developing health distress (Engelhard, van den Hout, & Schouten; 2006; Bjelland, Krokstad, Mykletun, Dahl, Tell, & Tambs, 2008). One explanation may be supported by the strong group cohesion which is usually developed in military units for operating efficiently, especially in infantry units under extreme stress (Ingraham & Manning, 1981; Shils Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 108  M. TROUSSELARD ET AL. Table 7. Predictors of Mindfulness (stepwise regression model). Population Predictors R2* R2* adjusted Beta B Std. Err. T Sign. T Constant 0.31 0.29 52.38 1.75 29.78 <.001 Anxiety-trait −0.18 −0.11 0.06 −1.88 .06 Vulnerability −0.37 −0.58 0.13 −4.17 <.001 Depression 0.12 0.15 0.14 1.05 .29 Full sample Hostility −0.27 −0.36 0.1 −3.42 <.001 Constant 0.62 0.43 37.53 12.72 2.95 .01 Anxiety-trait 0.53 0.87 0.4 2.16 .06 Vulnerability −0.31 −0.79 0.72 −1.1 .30 Depression 0.67 1.36 0.83 1.62 .14 High mindfulness group Hostility −0.75 −1.77 0.86 −2.06 .07 Constant 0.18 0.16 45.47 1.27 35.73 <.001 Anxiety-trait −0.07 −0.02 0.03 −0.68 .49 Vulnerability −0.28 −0.24 0.09 −2.58 <.001 Depression −0.06 −0.04 0.09 −0.48 .62 Middle mindfulness group Hostility −0.14 −0.1 0.07 −1.51 .13 Constant 0.21 0.05 30.23 1.82 16.58 <.001 Anxiety-trait −0.59 −0.1 0.05 −1.93 .06 Vulnerability 0.12 0.05 0.1 À.53 .6 Depression 0.6 0.23 0.11 1.99 .06 Low mindfulness group Hostility 0.08 0.03 0.09 0.31 .75 B, factor B; Beta, beta coefficient; Std. Err., Standard error of B; T, t-test; Sign. T, significance (T). & Janowitz, 1948), or to counter the problems of living to- gether shut away in an isolated environment on a long subma- rine mission. Indeed, it is well-known that cohesion creates a sense of commonality and shared experience, creating a social support mechanism (Griffith, 2002) that both protects against stressful conditions by helping members adjust to military situations and promotes further supportive interpersonal rela- tionships (Griffith & Vaitkus, 1999). Relationsh i ps be t ween Mindfu l ne ss and the Assessed Psychologi cal Variabl e s The second aim of the study was to analyse the relationship between mindfulness and various psychological dimensions, independently of the nature of mission and of self-reported stressful events (i.e., the stress levels experienced). Most of the studies evaluated the relationship between mindfulness and few psychological variables. Furthermore, psychological variables were only used to assess a psychological state or a psychologi- cal trait. One of the interests of our results was to allow brush- ing a more general psychological picture, associating both posi- tive and negative states and traits, of an individual according to its mindfulness level. With regard to the whole military sample, the correlations between FMI scores and those for measures of psychological variables showed a coherent picture. Low mindfulness is re- lated with high emotional disturbance levels (Neuroticism, Depression, Hostility, Impulsiveness, Anxiety, Alexithymia, emotion-oriented coping, and avoidance-oriented coping) and high mindfulness is related with positive emotions, (Extraver- sion, task-oriented coping and, at lesser extent, Openness). Considering only the highest Pearson correlation coefficients, we observed that low mindfulness was associated with high emotional disturbance, which agrees which complements oth- ers’ findings that high levels of mindfulness indicate a psycho- logical disposition associated with reduced negative appraisals of challenging or threatening events (Weinstein, et al., 2009). Whether or not mindfulness is related to introversion or extra- version (Baer, et al., 2006), individuals high in Extraversion are considered as sociable, active, experiencing positive emotions (Costa & McCrae, 1992) and to be associated with positive affects, optimism and well-being (Löckenhoff, et al, 2008), so the links observed among our soldiers between FMI and Extra- version and between FMI and positive emotions (E6) appear to be coherent, and to echo the strong positive links that have been observed between Extraversion and positive emotion with re- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 109  M. TROUSSELARD ET AL. silience (Campbell-sills, Cohan, & stein, 2006). Although data on the relationship between mindfulness and Conscientiousness are scarce, Conscientiousness has been found to serve as a protection against stress through its influ- ence on coping strategy selection leading to the greater use of Problem-Focused coping strategies among peacekeepers (Dir- kzwager, Bramsen, & van der Ploeg, 2003). Taken together with the previous correlations, the relationship between high mindfulness and high Conscientiousness suggests that mind- fulness is linked with a cognitive way of managing problems, and with optimism about the self, which is related to self-es- teem, which has been defined as a perception of oneself as having strong coping skills, persistence in the face of chal- lenges, happiness, and longevity (Bandura, 1982; Bauermeister, Campbell, Krueger, & Vohs, 2003; Chunping, Xiwen, Qian- zhen, Aili, Bo, & Yongping, 2010; Pruessner, Hellhammer, & Kirschbaum, 1999). Thus, a mindful individual appears as an achieving person with stable (C) and positive (E6) emotions, with a seeking ex- perience of the world (E), with a task-oriented coping attitude to adversity, a psychological pattern that suggests such indi- viduals may experience stress situations as less threatening to themselves and thus as less stressful. Finally, a high mindful- ness level may be viewed as an indicator of good adjustment following adversity—the more mindful individuals have less stressed brains and so recover from exposure to stressors more quickly. Such a psychological pattern of mindfulness raises the question of an overlap between it and resilience. Resilience has been negatively associated with Neuroticism, and positively related to Extraversion, Conscientiousness and optimism. Task-oriented coping has been positively related to resilience, and has been argued as mediating the relationship between Conscientiousness and resilience (Campbell-Sills, et al., 2006; Waugh, Fredrickson, & Taylor, 2008). Such a per- sonality pattern has been associated with more complete affec- tive recovery after aversive laboratory stress, suggesting that people are deemed resilient if they maintain psychological sta- bility and display an ability to recover effectively from daily stress experiences with fewer mental health problems (Waugh, et al., 2008), and these same adaptive outcomes in the face of adversity have also been observed in mindful individuals. Mindfulness level, therefore, may constitute a measure of resil- ience in our military sample—a score over 47 may indicate protective adaptation and highly resilient individuals, and one below 34 low resilient subjects who are maladapted to dealing with distress. Mindfulness and Stress Experience The third step was to analyse the sensitivity of the mindful- ness score to the stress experienced by our sample soldiers. One view is to consider stress experience as being objective, ana- lysable using four main variables: the number of missions linked to overall duration of active service, the operational dif- ference between populations, the rate of concern of health, and the rate of reported stress events. The results (which held for our full military population, i.e., both infantrymen and subma- riners) show that the FMI scores depended neither on the num- ber of missions, nor on active duty duration, nor on the reported total number of stressful events. However the psychological questionnaires showed that submariners had higher numbers of missions, a higher rate of stressful events, higher mindfulness levels, but were less stressed. Compared to mountain infantry- men, they tended to have lower trait-anxiety, avoidance-ori- ented coping, lower Neuroticism and alexithymia scores, and higher task-oriented coping, Agreeableness, and Openness to experience scores. Higher levels of stressful event reports may be due to higher numbers of submarine patrols (Corrigan & Penn, 1999, Reger, Gahm, Swanson, & Duma, 2009), but these findings not only conflict amongst themselves, but also with both the well-known association between mental distress rate and both mission durations and the ratio of deployments (Cor- rigan & Penn, 1999, Reger, et al., 2009) and the association previously observed between lower mindfulness scores and higher experience of stressful events in a non-military middle- aged population (Trousselard, et al, 2010). A first explanation for our data may come from a population selection bias based on personality differences between subma- riners and infantrymen, in that the choice of serving as subma- riner requires the ability to live within small groups isolated from the outside world. Although descriptions in the literature of submariners’ personality characteristics are scarce, studies have described them as highly homogeneous groups (van Wilk & Waters, 2000) but the specific personality factors observed depended on the dimensional outcomes measurements that were used. Similar problems exist for military personnel in general, but, again, since different studies have not used the same tests findings have differed according to the purpose of different studies. Psychologists have labelled and developed tests to understand personality correlates, to profile the person- ality styles of the successful professional soldier or successful military leaders, or even to help recruit people more likely to stay in military service for longer periods, so data are hetero- geneous between different armed forces and different military groups. In terms of the psychological dimensions assessed in our sample on the NEO-PIR scale (Carter, Herbst, Stoller, King, Kidorf, Costa, & Brooner, 2001; Marshall, De Fruyt, Rolland, Bagby, 2005), the Alexithymia scale (de Timary, Luts, Hers, & Luminet, 2008; Stingl, Bausch, Walter, Kagerer, Leichsenring, & Leweke, 2008), the CISS (Gaudreau & Miranda, 2010) and the anxiety trait scale (Endler & Kocovski, 2001), they can be considered as being relatively stable over time for non-clinical samples. Nevertheless, changes in scores have been described when subjects suffer distress, as in NEO-PI-R scores for the Neuroticism (Wilberg, Karterud, Pedersen, Urnes, & Costa, 2009). Whether the differences in psychological dimensions as- sessed in this study constitute a selection bias cannot be entirely refuted, but this must be qualified given the level of distress outcomes observed among infantrymen, as indicated by their higher rates of both health concerns and of stressful profes- sional events reported. As these data clearly depend on the effects of the job on individuals, another explanation may come from the nature of the missions themselves. Submariners are part of a nuclear deterrence force whereas infantrymen are de- ployed in conflict areas. While some stressors are common to both populations (extended separation from family members, working day and night, sleep debt, etc.), others differ: in par- ticular, infantry deployments carry the risks related to combat situations—being attacked or ambushed, confronting dead bod- ies, having someone you know seriously injured or killed, all of which are known to create a high level of stress, and to lead to infantrymen experiencing higher numbers of stressful events than submariners. Consequently, our objective stress experience Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 110  M. TROUSSELARD ET AL. analyses highlighted two different patterns of relationships between mindfulness and stress experience, one for submarin- ers (characterized by high numbers of patrols, high rates of private stressful events, low rates of health concerns and higher mindfulness levels), and the other for infantrymen (less patrols, more professional stressful events, greater health concerns and lower mindfulness levels). The first is similar to previous data from a middle-aged non clinical civilian population (Trousse- lard, et al., 2010) and may be considered as adaptive, whereas the second represents a different professional stress context, which is more associated with distress. In order to understand better how stress and mindfulness may interact, the subjective stress experience point of view was also taken into account. Indeed, it is common assumption among health studies that the impact of events that are “objectively” stressful is, to some degree, determined by individuals’ percep- tions of their stressfulness (see, e.g., Lazarus, 1966; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). This approach can involve questionnaires to check anxiety-state, alexithymia, and coping style, which are known to reflect individuals’ psychological states at the mo- ment of the measures, and thus the subjective effect of the “ob- jective” stress they are experiencing. Anxiety, the outcome most frequently observed in stressor-exposed men, has been identified as the primary phenomenon of stress and to have strong correlations with objective stress in various populations (Cerclé, Gadea, Hartmann, & Lourel, 2008; Cohen, Kamarck, & Mermelstein, 1983; Bergdahl & Bergdahl, 2002; Fliege, Rose, Arck, Walter, Kocalevent, Weber et al, 2005). Our find- ings of higher anxiety-state levels in infantrymen than in sub- mariners indicate their higher stress-experience. Alexithymia characteristics mediate cognitive and affective appraisal be- tween stressors and stress responses (Berthoz, et al., 1999; Espina-Eizaguirre, Saenz de Cabezon, Ochoa de Alda, Olariaga, & Juaniz, 2004; Karukivi, Hautala, Kaleva, Haapasalo-Pesu, Liuksila, Joukamaa, & Saarijärvi, 2010; Mikolajczak & Lumi- net, 2006). Alexithymia is also known to contribute to acute stress disorder, and the TAT score is known to be modified by encountering stress (Martinez-Sanchez, Ato-Garcia, Corcoles, Huedo, & Selva, 1998, 2003; Mikolajczak & Luminet, 2006). Although the difference between the two military units was not very great, the infantry groups tended to report higher TAT levels. This was mainly observed for the “identification of feelings” factor, suggesting a difference in emotional self-aware- ness. This difficulty in distinguishing between feel- ings and the bodily sensations of emotional arousal is closely related to sensitivity to the emotions of others (Lane, 2000; Lane & Schwartz, 1987). An individual’s capacity to perceive and to differentiate their own emotions from those of another person in a given context appears to be crucial for their ability to manage a variety of emotional states (Bydlowski, Corcos, Jeammet, Paterniti, Berthoz, Laurier, Chambry, & Consoli, 2005). For those unable to perceive this differentiation, emo- tions remain global and undifferentiated, reducing their ability to use their own emotions to guide their selection of adaptive behaviour. This suggests that infantrymen’s deployments may disturb their emotional self-awareness and thus lead to their non optimal adaptation to their environment. As the effects of stress are directly linked to coping styles, coping is a useful concept in understanding an individual’s adaptive capacity and their vulnerability to stress-related dis- ease. Coping styles have been characterized (in both humans and animals) as presenting consistent behavioural and neuro- endocrine characteristics (Hori, Ozeki, Teraishi, Matsuo, Ka- wamoto, Kinoshita, Suto, Terada, Higuchi, & Kunugi, 2010; Koolhaas, Korte, De Boer, Van Der Vegt, Van Reenen, Hopster, De Jong, Ruis, Blokhuis, 1999; Salvador & Costa, 2009). Re- silience is viewed as an important coping style, which allows an individual to recover from or avoid the negative outcomes of stressor conditions and which follows a pattern of high task- oriented coping and low emotionally-oriented and low avoid- ance-coping styles, more use of problem solving and social support-seeking strategies, and so being related to lower PTSD symptom severity (Dirkzwager, et al., 2003). Longitudinal studies have shown that individuals’ styles of coping change over time (Kammeyer-Mueller, Judge, Scott, 2009; Stewart & Schwarzer, 1996). Intensive and inappropriate emotional reac- tions show the greatest cross-situational stability and problem solving efforts the least (Stewart & Schwarzer, 1996), and re- search has described a tendency to shift toward a more emo- tional- and/or avoidance-coping style when confronting intense stressors (Foa & Kozak, 1986; Horowitz, 1986). However, which coping styles are the most or least sensitive to changing according to the stressful situations encountered is still matter of debate (Dirkzwager, et al., 2003; Kammeyer- Mueller, Judge, Scott, 2009). Different coping patterns were observed between the two military units: while no differences in emotion-oriented coping levels were noticed, we found the infantrymen used fewer task-oriented and more avoidance- oriented strategies than did the submariners. The data from the alexithymia literature indicates that, while no difference was observed between the two units in emotion-oriented coping, this coping strategy could be disturbed in the less mindful in- fantrymen (Bydlowski, et al., 2005; Lane, et al., 2000; Lane & Schwartz, 1987). Low mindfulness levels, which clearly appear to be associated with less efficient adaptation towards coping with emotions, could induce a possible shift toward more dis- turbed emotional relationships with the environment. In line with the suggestions in the literature that lower mindfulness levels are linked to higher stressful situations encountered, this pattern was observed in infantrymen confronted with highly stressful situations. The difference in natures of the two units’ missions may ac- count for the discrepancy in the distribution of their FMI scores, with twice as many infantrymen as submariners recording scores below the “normal” range, and only half as many regis- tering sores above normal. On the basis of subjective stress experience, and referring to the FMI score distribution we ob- served, we can propose a descriptive dual model of the extent to which mindfulness score might be accounted for by the four psychological constructs (anxiety, vulnerability, hostility, de- pression, neuroticism). The highest negative association be- tween mindfulness and the assessed psychological constructs was observed for subjects at the highest extreme of the mind- fulness range. This association was less important for the sub- jects in the normal range. While this model was very good or acceptable for 79% of the military sample, it was not acceptable for the 21% who exhibited the lowest mindfulness scores. The observations that both the percentage of individuals in the lower range of mindfulness distribution was higher for in- fantrymen (21%) than for submariners (10%), and that that in the higher range was lower for infantrymen (5%) than for sub- mariners (13%) raises a final question as to whether mindful- ness measures may be altered by exposure to stressors. In our study, the difference in mindfulness measurements between Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 111  M. TROUSSELARD ET AL. both groups is viewed as the consequence of stress exposure, rather than of selection bias in the assessed population. Al- though no difference was observed in terms of relationship between mindfulness and socio-demographic features between civilian and military populations, a selection bias from the dif- ferent personality profiles of individuals entering the different armed forces cannot be discounted, given the lack of common assessments of such recruits. Independent of the possibility of a selection bias between submariners and infantrymen, this aspect focuses on the stability of the mindfulness dimension. Whether an individual’s mindfulness score remains exactly the same across time and situation (i.e., is absolutely stable) is not known: no studies have measured mindfulness changes when individu- als face the fluctuating situations encountered in life, nor have any investigated whether mindfulness changes after the chronic or acute increases in psychological distress that might be en- countered by infantrymen on deployment. However many studies have examined mindfulness after chronic reductions in psychological distress: indeed, mindful- ness training - a two hour a week intervention over eight weeks for reduction in psychological distress—has clearly been shown to increase mindfulness level in both clinical and non clinical subjects (Hayes, et al., 1999; Germer, et al., 2005; Grossman, Niemann, Schmidt, & Walach, 2004; Weinstein, et al., 2009; Lau, Bishop, Segal, Buis, Anderson, Carlson, Shapiro, & Car- mody, 2006), although none give information to investigate whether the mindfulness scores possess arithmetical properties indicating partial stability. Specifically, it would be interesting to know whether the relative differences between individual scores remain the same during the mindfulness training, and whether, even if they do, the relative positions of individuals within a group remains the same. Such data could assist in the investigation of mindfulness as a personality trait, or as a state-dependant phenomenon, or as an interaction between trait and state. It could also help to conceptualize categories of mindfulness or continuous dimensions for analysing it. More interesting in clinical terms, is that the few studies in- vestigating long term benefits of meditation have shown sus- tainable effects on cognitive functions, brain plasticity and mental health (Aftanas & Golosheykine, 2005; Jha, Kromp- inger, & Baime, 2007; Lazar, Kerr, Wasserman, Gray, Greve, Treadway, McGarvey, et al., 2005; Slagter, Lutz, Greischar, Francis, Nieuwenhuis, Davis, & Davidson, 2007). Although these findings provide neurophysiological evidence to support claims of the long-term effects of meditation on emotional sta- bility, detachment and resilience to stressful events, other stud- ies have also shown experience-dependent “dose”-effects of meditation on these neurofunctional networks (Aftanas & Golocheikine, 2001, 2002; Brefczynski-Lewis, Lutz, Schaefer, Levinson, & Davidson, 2007; Farb, Segal, Mayberg, Bean, McKeon, Fatima, & Anderson, 2007). These data from mind- fulness training suggest that it works by changing the way mental events are experienced as they arise, on a continuum according to the time for achieving long term change in the neurophysiology for practitioners of Mindfulness Meditation, although these studies do not reveal whether or not individuals remain in the same category after completing the mindfulness training programs. However, our findings may indicate a continuum in the mindfulness level of individuals which could shape the brain, in terms of learning and experience-dependent plasticity, allowing it to govern the functional cerebral networks when the individ- ual is faced with stress experiences. On this continuum, the stress encountered could induce three separate patterns of func- tioning, according to the intensity of the stressors and the level of mindfulness. Above the normal range could be well adapted individuals, with a high level of mindfulness who we can con- sider resilient, and associated with lower psychological distress and psychopathology costs when facing the allostatic load of a stress experience (Seeman, Singer, Rowe, Horowitz, & McE- wen, 1997). The normal range may defined as containing indi- viduals who adapt themselves to face the stress experiences they encounter by using responses that are graded in relation to the allostatic load involved. The lower range category displays a pathological adaptation, with no assessed relationship be- tween mindfulness and distress—for such individuals, mind- fulness may have no reality, so a mindfulness questionnaire is unfruitful. These propositions should be considered in light of all of this study’s limitations: no recruiting data, no baseline for the levels of mindfulness, no PTSD scale, or for other pathologies derived from stress. The proposed hypotheses imply the need to con- duct longitudinal epidemiologic studies evaluating the epige- netic development of mindfulness levels to investigate whether the properties of mindfulness can be thought of as being on a continuum. Further studies are also required to evaluate whether individual differences in mindfulness scores as meas- ured after stress experiences may be accounted for by individ- ual differences in baseline mindfulness scores. Neurophysi- ological studies to test functional and structural changes before and after stress experiences could help evaluate the categories of individuals’ responses, and so help understand the neuro- physiological functioning of individuals below the normal range after a high stress experience. To sum up, our results first have contributed to build a psy- chological picture of psychological functioning for military according to the mindfulness level. Second, they have allowed evaluating how mindfulness may help to deal with stress for individuals confronted with realistic stressors. Finally, because mindfulness has to be seen in the context of stress and suffering, these results are of outstanding importance for health care and health care research. REFERENCES Aftanas, L. I., & Golosheykine, S. A. (2005). Impact of regular medita- tion practice on EEG activity at rest and during evoked negative emotions. International Journal of Ne ur o s ci e n ce , 115, 893-909. doi:10.1080/00207450590897969 Aftanas, L. I., & Golocheikine, S. A. (2001). Human anterior and fron- tal midline theta and lower alpha reflect emotionally positive state and internalized attention: High resolution EEG investigation of meditation. Neu r o s c i e n c e Letters, 310, 57-60. doi:10.1016/S0304-3940(01)02094-8 Aftanas, L. I., & Golocheikine, S. A. (2002). Non-linear dynamic com- plexity of the human EEG during meditation. Neuroscience Letters, 330, 143-146. doi:10.1016/S0304-3940(02)00745-0 Alport, G. W. (1961). Pattern and growth in personality. New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart & Winston. Arrindell, W. A., Sanavio, E., & Sica, C. (2002). Introducing a short form version of the Scale of Interpersonal Behaviour (s-SIB) for use in Italy. Psicoterapia Cognitiva e Comportamentale, 8, 3-18. Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., & Allen, K. B. (2004). Assessment of mind- fulness by self-report: The Kentucky Inventory of mindfulness Skills. Assessment, 11, 191-206. doi:10.1177/1073191104268029 Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Hopkins, J., Krietemeyer, L., Toney, L., et al., Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 112  M. TROUSSELARD ET AL. (2006). Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Ass e ssment, 13, 27-45. doi:10.1177/1073191105283504 Bagby, R. M., Parker, J. D., & Taylor, G. J. (1994). The twenty-item Toronto alexithymia scale-I. Item selection and cross validation of factor structure. Journal of Psychosomat i c Research, 38, 23-32. doi:10.1016/0022-3999(94)90005-1 Bagby, R. M., Taylor, G. J., & Parker, J. D. (1994). The twenty-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale-II. Convergent, discriminant, and con- current validity. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 38, 33-40. doi:10.1016/0022-3999(94)90006-X Bandura, A. (1982). Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. American Psychologist, 37, 122-147. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.37.2.122 Bauermeister, R. F., Campbell, J. D., Krueger, J. I., & Vohs, K. D. (2003). Does high self-esteem cause better performance, inter-per- sonal success, happiness, or healthier lifestyles? Psychological Sci- ence in the Public Interest, 4, 1-44. doi:10.1111/1529-1006.01431 Bergdahl, J., & Bergdahl, M. (2002). Perceived stress in adults: Preva- lence and association of depression, anxiety, and medication in Swedish population. Stress and Heal th, 18, 235-241. doi:10.1002/smi.946 Berthoz, S., Consoli S., Perez-Diaz, F., & Jouvent, R. (1999). Alexithymia and anxiety: Compounded relationships? A psychomet- ric study. European Psychiatry, 14, 372-378. doi:10.1016/S0924-9338(99)00233-3 Bjelland, I., Krokstad, S., Mykletun, A., Dahl, A. A., Tell, G. S., & Tambs, K. (2008). Does a higher educational level protect against anxiety and depression? The HUNT study. Social Science & Medi- cine, 66, 1334-1345. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.12.019 Brefczynski-Lewis, J. A., Lutz, A., Schaefer, H. S., Levinson, D. B., & Davidson, R. J. (2007). Neural correlates of attentional expertise in long-term meditation practitioners. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 104, 11483- 11488. doi:10.1073/pnas.0606552104 Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social P s y chology, 84, 822-848. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822 Bydlowski, S., Corcos, M., Jeammet, P., Paterniti, S., Berthoz, S., Laurier, C., Chambry, J., & Consoli S. (2005). Emotion-processing deficits in eating disorders. International Journal on Eating Disor- ders, 37, 321-329. doi:10.1002/eat.20132 Campbell-Sills, L., Cohan, S. L., & Stein, M. B. (2006). Relationship of resilience to personality, coping, and psychiatric symptoms in young adults. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44, 585-599. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2005.05.001 Carter, J. A., Herbst, J. H., Stoller, K. B., King, V. L., Kidorf, M. S., Costa Jr., P. T., & Brooner, R. K. (2001). Short-term stability of NEO-PI-R personality trait scores in opioid-dependent outpatients. Psychology of Addictive Behaviours , 15, 255-260. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.15.3.255 Cattell, R. B. Cattell, A. K., Cattell, H. E. P., & Kelly, M. L. (1999) The 16PF select manual. Champaign, IL: Institute for Personality and Ability Testing. Cerclé, A., Gadea, C., Hartmann, A., & Lourel, M. (2008). Typological and factor analysis of the perceived stress measure by using the PSS scale. European Review of Applied Psychology, 58, 227-239. doi:10.1016/j.erap.2008.09.006 Cohen, J. (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral. Sciences. Hillsdale, NY: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates. Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behaviour, 24, 385- 396. doi:10.2307/2136404 Chunping, N., Xiwen, L., Qianzhen, H., Aili, L., Bo, W., & Yongping, Y. (2010). Relationship between coping, self-esteem, individual fac- tors and mental health among Chinese nursing students: A matched case—Control study. Nurse Education Today, 30, 338-343. Corcos, M., & Sperenza, M. (2003). Psychopathologie de l'alexithymie Approche des troubles de la régulation affective. [Psychopathology of alexithymia: The affective regulation of the symptoms]. Collection: Psychothérapies, Dunod. Corrigan, P. W., & Penn, D. L. (1999). Lessons from social psychology on discrediting psychiatric stigma. American Psychiatry, 54, 765-776. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.54.9.765 Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). Revised NEO Personality Inven- tory (NEO PI-R) ant the five NEO-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI): professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Re- sources. Cox, B. J., Endler, N. S., & Swinson, R. P. (1991). Clinical and non clinical panic arracks: An empirical test of panic-anxiety continuum. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 5, 21-34. doi:10.1016/0887-6185(91)90014-K Davidson, R. J. (2004). Well-being and affective style: Neural sub- strates and biobehavioural correlates. Philosophical transactions of the Royal society of London. Series B, 359, 1395-1411. de Timary, P., Luts, A., Hers, D., & Luminet, O. (2008). Absolute and relative stability of alexithymia in alcoholic impatients undergoing alcohol withdrawal: Relationship to depression and anxiety. Psy- chiatry Research, 15, 105-113. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2006.12.008 Dirkzwager, A. J. E., Bramsen, I., & Ploeg, H. M. (2003). Social sup- port, coping, life events, and posttraumatic stress symptoms among former peacekeepers: A prospective study. Personality and Individ- ual Differences, 34, 1545-1559. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00198-8 Dobkin, P. (2008). Mindfulness-based stress reductin: What processes are at work? Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 14, 8-16. doi:10.1016/j.ctcp.2007.09.004 Eifert, G. H., & Heffner, M. (2003). The effects of acceptance versus control contexts on avoidance of panic-related symptoms. Journal of Behavioural Therapy and Explora tory Psychology, 34, 293-312. doi:10.1016/j.jbtep.2003.11.001 Endler, N. S., & Kocovski, N. L. (2001). State and trait anxiety revis- ited. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 15, 231-245. doi:10.1016/S0887-6185(01)00060-3 Endler N. S., & Parker J. D. A. (1999). Coping inventory for stressful situations (CISS) manual (2nd Ed.). Toronto, Canada: Multi- Health Systems. Engelhard, I. M., Van den Hout, M. A., & Schouten, E. G. W. (2006). Neuroticism and low educational level predictive for the risk of post-traumatic stress disorder in women after miscarriage or stillbirth. General hospital psychiatry, 28, 414-417. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2006.07.001 Farb, N. A. S., Segal, Z. V., Mayberg, H., Bean, J., McKeon, D., Fatima, Z., & Anderson, A. K. (2007). Attending to the present: Mindfulness meditation reveals distinct neural modes of self-reference. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 313-322. 2, doi:10.1093/scan/nsm030 liege, H., Rose, M., Arck, P., Walter, O., Kocalevent, R., Weber, C., et al. (2005). The Perceived Stress Questionnaire (PSQ) reconsidered: Validation and reference value from different clini adult samples. Psychosomat ic M ed ic in e, 67 F cal and healthy , 78-88. doi:10.1097/01.psy.0000151491.80178.78 oa, E. B., & Kozak, M. J. (1986); Emotional processing of fear: Ex-F Fg: Pitfalls and promise. posure to corrective information. Psychologic a l Bulletin, 99, 20-35. olkman, S., & Moskowitz, J. T. (2004). Copin Annual Review of psychology, 55, 745-774. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141456 riedman, H. S. (2000). Long-terms relations of personality and health: Dynamisms, mechanisms, tropisms. Jour Fnal of Personality, 68, 1089- 1108. doi:10.1111/1467-6494.00127 rewen, P. A., Lanius, R. A., Dozois, D. J. A., Neufeld, R. W. J., Pain, C., Hopper, J. W., Densmore, M., & Stevens, T. K. (2008). Clinical and neural correlates of alexithymia in PTSD. Journal of Abn F ormal Psychology, 117, 171-181. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.117.1.171 audreau, P., & Miranda, D. (2010). Coping across time, situations, and contexts: A conceptual and methodological overview of stability, consistency, and change. In A. Nicholls (Ed.), Coping in sport: Concepts, theories, and related con G struct (pp. 15-32). New York, Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 113  M. TROUSSELARD ET AL. NY: Nova Science. ermer, C. K., Siegel, R., & Fulton, P. (2005).G Mindfulness and psy- G of Affective Disorders, 123, chotherapy. New York, NY: Guilford Press. inzburg, K., Ein-Dor, T., & Solomon, Z. (2010). Comorbidity of posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety and depression: A 20-year lon- gitudinal study of war veterans. Journal 249-257. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2009.08.006 riffith, J. (2002). Multilevel analysis of cohesion’s relation to stress, well-being, identification, disintegration an ness. Military Psy chol ogy, 14, 217-2 G d perceived combat readi- 39. doi:10.1207/S15327876MP1403_3 iffith, J., & Vaitkus, M. (1999). Relating cohesion to stress, strain, disintegration, and performance: An organizing framework. Gr Military Psychology, 11, 27-55. doi:10.1207/s15327876mp1101_3 ossman, P., Niemann, L., Schmidt S., & Walach, H. (2004). Mind- fulness-based stress reduction and health benefit Journal of Psychosomatic Re sea rch , 57 Gr s: A meta-analysis. , 35-43. doi:10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00573-7 aviland, M. G., Shaw, D. G., Cummings, M. A., & MacMurray, J. P. (1988). Alexithymia: Subscales and relationship chotherapy and Psychoso H to depression. Psy- matics, 50, 164-170. doi:10.1159/000288115 ayes, S. C., Strosahl, K. D., & Wilson, K. G. (1999). Acceptance and H H y and depression. 56, 227-237. commitment therapy. New York, NY: Guilford Press. endryx, M. S., Haviland, M. G., & Shaw, D. G. (1991). Dimensions of alexithymia and their relationships to anxiet Journal of Personality Assessment, doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa5602_4 endryx, M. S., Haviland, M. G., Shaw, D. G. & Henry, J. (1994). Alexithymia in women and men hospitalized for psychoactiv stance dependence. Co mprehensive Ps H e sub- ychiatry, 35, 124-128. doi:10.1016/0010-440X(94)90056-N onkalampi, K., Hintikka, J., Saarinen, P., Lehtonen, J., & Viinamäki, H. (2000). Is alexithymia a permanent feature in depressed patients? Results from 6-month follow-up study. Psychot H herapy and Psycho- somatics, 69, 303-308. doi:10.1159/000012412 ori, H., Ozeki, Y., Teraishi, T., Matsuo, J., Kawamoto, Y., Kinoshita, Y., Suto, S., Terada, S., Higuchi, T., & Kunugi, H. (2010). Relation- ships between psychological distress, coping styles, and HPA axis reactivity in healthy adults. Journal of Psych H iatry Research, 44, 865-873. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.02.007 orowitz, MH. (1986). Stress response syndromes. Northvale, NJ: H ronic kidney disease. Jour- 9-76. Aronson. oth, K. F., Christensen, A. J., Ehlers, S. L., Raichle, K. A., & Lawton, W. J. (2007). A longitudinal examination of social support, agree- ableness, and depressive symptoms in ch nal of Behavioral Medecin e, 30, 6 doi:10.1007/s10865-006-9083-2 graham, L. H., & Manning, F. J. (1981In). Cohesion: Who needs it, Jh Behavioral what is it? Military Review, LXI, 2-12. a, A. P., Krompinger, J., Baime, M. J. (2007). Mindfulness training modifies subsystems of attention. Cognitive Affective & Neuroscience, 7, 109-119. doi:10.3758/CABN.7.2.109 rram, K. L., & Coleman, P. G. (1999). The big five personality traits and reporting of health problems and health behav British Journal of Health Psycho Je iour in old age. logy, 4, 181-192. doi:10.1348/135910799168560 ster, R. P., McEwen, B. S., & Lupien, S. J. (2010). Allostatic load biomarkers of chronic stress and impact on health Neuroscience and Bi o b ehavioral Revie Ju and cognition. ws, 35, 2-16. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.10.002 abat-Zinn, J. (1990). Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and K mind to face stress, pain and illness. New-York, NY: KJournal of Applied Delacourt. ammeyer-Mueller, J. D., Judge, T. A., & Scott, B. A. (2009). The role of core self-evaluations in the coping process. Psychology, 94, 177-195. doi:10.1037/a0013214 arukivi, M., Hautala, L., Kaleva, O., Haapasalo-Pesu, K. M., Liuksila, P. R., Joukamaa, M., & Saarijärvi, S. (2010). Alexithymia is associ- ated with anxiety among adolescents. Journal 125, 383-387. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2010.02.126 ohls, N., Sauer, S., & Walach, H. (2009). Facets of mindfulness— results of an online study investigating the Freiburg mindfulnes ventory. Personality and Individu K s in- al Differences, 46, 224-230. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2008.10.009 oolhaas, J. M., Korte, S. M., De Boer, S. F., Van Der Vegt, B. J., Van Reenen, C. G., Hopster, H., De Jong, I. C., Ruis, M. A., & Blokhuis, H. J. (1999). Coping styles in animals: Current status in behaviour and stress-physiology. Neurosciences Biobeh K avioral Review, 23, 925-935. doi:10.1016/S0149-7634(99)00026-3 ane, R. D., Sechrest, L., Riedel, R., Shapiro, D. E., & Kazniak, A. W. (2000). Pervasive emotion recognition deficit common to alexithy- mia and t L he repressive coping style. Psychosomatic Medicine, 62, L psychopa- L al of Clinical Psy- 492-501. ane, R. D., & Schwartz, G. E. (1987). Levels of emotional awareness: A cognitive-developmental theory and its application to thology. American J ou r na l of Psychiatry, 144, 133-143. au, M. A., Bishop, S. R., Segal, Z. V., Buis, T., Anderson, N. D., Carlson, L., Shapiro, S., & Carmody, J. (2006). The Toronto mind- fulness scale: development and validation. Journ chology, 62, 1445-1467. doi:10.1002/jclp.20326 azar, S. W., Kerr, C. E., Wasserman, R. H., Gray, J. R., Greve, D. N., Treadway, M. T., McGarvey, M., Quinn, B. T., Dusek, J. A., Benson, H., Rauch, S. L., Moore, C. I., & Fischl, B. (2005). Meditation ex- perience is associated with increased cortical thickness. Neu L roreport, 16, 1893-1897. doi:10.1097/01.wnr.0000186598.66243.19 azarus, R., & FolkmanL, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New Lological stress and the coping process. L y, 35, 747-766. York, NY: Springer. azarus, R.S. (1966). Psych New York, NY: Springer. evitt, J. T., Brown, T. A., Orsillo, S. M., & Barlow, D. H. (2004). The effects of acceptance versus suppression of emotion on subjective and psychological response to carbon dioxide challenge in patients with panic disorder. Behavioral Therap doi:10.1016/S0005-7894(04)80018-2 inehan, M. M. (1993). Cognitive-behavioral treatment Lof borderline L earch in Personality, 42, 1334-1346. personality disorder. New York, NY: Guilford Press. öckenhoff, C. E., Sutin, A. R., Ferruci, L., & Costa, P. T. (2008). Personality traits and subjective health in the later years: The asso- ciation between NEO-PI-R and SF-36 in advanced ages is influenced by health status. Journal of Res doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2008.05.006 arshall, M. B., De Fruyt, F., Rolland, J. P., & Bagby, R. M. (2005). Socially desirable responding and the factorial s PI-R. Psychological Assessment, 17, M tability of the NEO 379-384. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.17.3.379 artínez-Sánchez, F., Ato-Garcia, M., Córcoles, E., Huedo, T., & Selva, J. (1998). Stability in the alexithymia levels: A longitudinal analysis of temporary series on various emotion ality and Individual Differen c e s , 2 4 , 76 M al answers. Person- 7-772. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(97)00239-0 artinez-Sanchez, F., Ato-Garcia, M., & Ortiz-Soria, B. (2003). Alex M ithymia—State or trait? Spanish Journal of Psychology, 6, 51- Micine, 153, 2093- 59. c Ewen, B. S., & Stellar, E. (1993). Stress and the individual: Mecha- nisms leading to disease. Archives of Internal Med 2101. doi:10.1001/archinte.1993.00410180039004 ikolajczak, M. & Luminet, O. (2006). Is alexithymia affected by situational stress or is it a stable trait related to emotion Personality and Individual Differ M regulation. ences, 40, 1399-1408. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2005.10.020 rsillo, S. M., Roemer, L., Lerner, J. B., & Tull, M. T. (2004). Accep- tance, mindfulness, and cognitive-behavioral therapy: comparisons, contrasts, and application to anxiety. In S. C. Hayes, V. M. Follette, & M. M. Linehan (Eds.), Mindfulness and acceptance: Expanding the cognitive-beh O avioural tradition (pp. 66-95). New York, NY: P ta-ana- ral Medicine, 25, 551-603. Guilford Press. enley, J. A., Tomaka, J., & Wiebe, J. S. (2002). The association of coping to physical and psychological health outcomes: A me lytic review. Journal of behaviou K of Affective Disorders, Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 114  M. TROUSSELARD ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 115 doi:10.1023/A:1020641400589 orcelli, P., Leoci, C., Guerra, V., Taylor, G. J., & Bagby, R. M. (1996). A longitudinal study of alexithymia and psychological distress in in- flammatory bowel disease. Journal of Psychoso P matic Research, 41, 569-573. doi:10.1016/S0022-3999(96)00221-8 uessner, J. C., Hellhammer, D. H., & Kirschbaum, C. (1999) Low self-esteem, induced failure and the adrenocortical st Personality and Individual Differences Pr ress response. , 27, 477-489. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(98)00256-6 eger, M. A., Gahm, G. A., Swanson, R. D., & Duma, S. J. (2009). Association between number of deployments to Iraq and mental health screening outcomes in U.S. Army soldiers. Journa R l of Clinical Psychiatry, 70, 1266-1272. doi:10.4088/JCP.08m04361 eips, U. D. (2002). Standards for inte ploratory Psychology, 49, 243-256 Rrnet-based experimenting. Ex- . doi:10.1026//1618-3169.49.4.243 olland, J. P. (1998). Qualités psychométriques de la traduction française de l’inventaire de personnalité NEO-PI-R (étude prélimi- naire). Revue Française et Fran R cophone de Psychiatrie et de Psycho- SNeurosciences and logie Médicale, 18, 139-144. alvador, A., & Costa, R. (2009). Coping with competition: Neuroen- docrine responses and cognitive variables. Biobehavioral Review, 33, 160-170. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.09.005 apolsky, R. M. (2001). Atrophy of the hippocampus in post stress disorder: How and Straumatic when? Hippocampus, 11, 90-91. doi:10.1002/hipo.1026 ecord, P. F., & Jouard, S. M: (1953). The appraisal of body-cathexis: Body-cathexis and the self. Jour Snal of Consulting Psychology, 17, 343-347. doi:10.1037/h0060689 eeman, T. E., Singer, B. H., Rowe, J. W., Horowitz, R. I., & McEwen, B. S. (1997). Price of adaptation—Allostatic load and its health con- sequences: MacArthur studies of s ternal Medicine, 157, 2259-2268. S uccessful aging. Archives of In- doi:10.1001/archinte.1997.00440400111013 egal, Z. V., Williams, J. M. G., & Teasdale, J. D. (2002). Mindful- ness-based cognitive therapy for depression: A new S approach to S lation and health. Ad- Sfile of mood states. S r II. Public Opinion Quarterly, 12, 280-315. preventing relapse. New York, NY: Guilford Press. hapiro, S. L., & Schwartz, G. E. R. (1999). Intentional systemic mindfulness: an integrative model for self-regu vances in Mind-Body Medicine, 15 , 128-134. hacham, S. (1983). A shortened version of the pro Journal of Personality Assessment, 47, 305-306. hils, E. A., & Janowitz, M. (1948). Cohesion and disintegration in the Wehrmacht in World Wa doi:10.1086/265951 lagter, H. A., Lutz, A., Greischar, L. L., Francis, A. D., Nieuwenhuis, S., Davis, J. M., & Davidson, R. J. (2007). Mental training affects distribution of limited brain resources S . PLoS Biology, 5, 1228-1235. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0050138 pielberger C. D. (1983). Manual for the State-Trait-Anxiety InvenStory: S dinal study. Personality and Indi- STAI (form Y). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press. tewart, S. M., & Schwarzer, R. (1996). Stability of coping in Hong Kong medical students: A longitu vidual Differences, 20, 245-255. doi:10.1016/0191-8869(95)00162-X tingl, M., Bausch, S., Walter, B., Kagerer, S, Leichsenring, F., & Leweke, F. (2008). Effects of inpatient psychotherapy on the stability of alexithymia characteristics. Journal of Psychoso S matic Research, 65, 173-180. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.01.010 trozzi-Heckler, R. (2003). In search of warrior spirit: Teaching awareness disciplines to the Green Berets. Expanded Third Edition with Marine S Martial Art Update. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic T for treatment. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 141, 725- Totherapy and Books. aylor, G. J. (1984). Alexithymia: Concept, measurement, and implica- tions 732. aylor, G. J., Ryan, D., & Bagby, R. M. (1985). Toward the develop- ment of a new self-report alexithymia scale. Psych Psychosomatic, 44, 191-199. doi:10.1159/000287912 rousselard, M., Steiler, D., Raphel, C., Cian, C., Duymedjian, R., Claverie, D, & Canini, F. (2010). Validation of a French version of the freiburg mindfulness inventory—Short version: Relationships between mindfulness and stress in an adult population T . Biopsychoso- cial Medicine, 4, 1-11. doi:10.1186/1751-0759-4-8 alach, H., Buchheld, N., Buttenmüller, V., Kleinknecht, N., & Schmidt, S. (2006). Measuring mindfulness—The Freiburg Mind- fulness Inventory (FMI). Personality and Indi W vidual Differences, 40, 1543-1555. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2005.11.025 augh C. E., Fredrickson B .L., & Taylor, S. F. (2008). Adapting to life’s slings and arrows: Individual differences in resilience when recovering from an anticipated threat. Journal of Rese W arch in Per- sonality, 42, 1031-1046. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2008.02.005 einstein, N., Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2009). A multi-method examination of the effects of mindfulness on stress attribution, cop- ing and, emotional well-being. Journal of R W esearch in Personality, 43, 374-385. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2008.12.008 ilberg, T., Karterud, S., Pedersen, G., Urnes, Ø., & Costa, P. T. (2009). Nineteen-Month Stability of Revised NEO Personality In- ventory Domain and Facet Scores in Patients with Personality Dis- orders. The Journal of N er vo us an d Men W tal Disease, 197, 187-195. doi:10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181923fa0 eidner, M. & Saklofske, D. (1996). Adaptative and maladaptative coping. In M. Zeidner, & N. S. Endler (Eds), Handbook of coping: Theory, re Z search and application (pp. 505-531). Oxford, England: Wiley.