Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

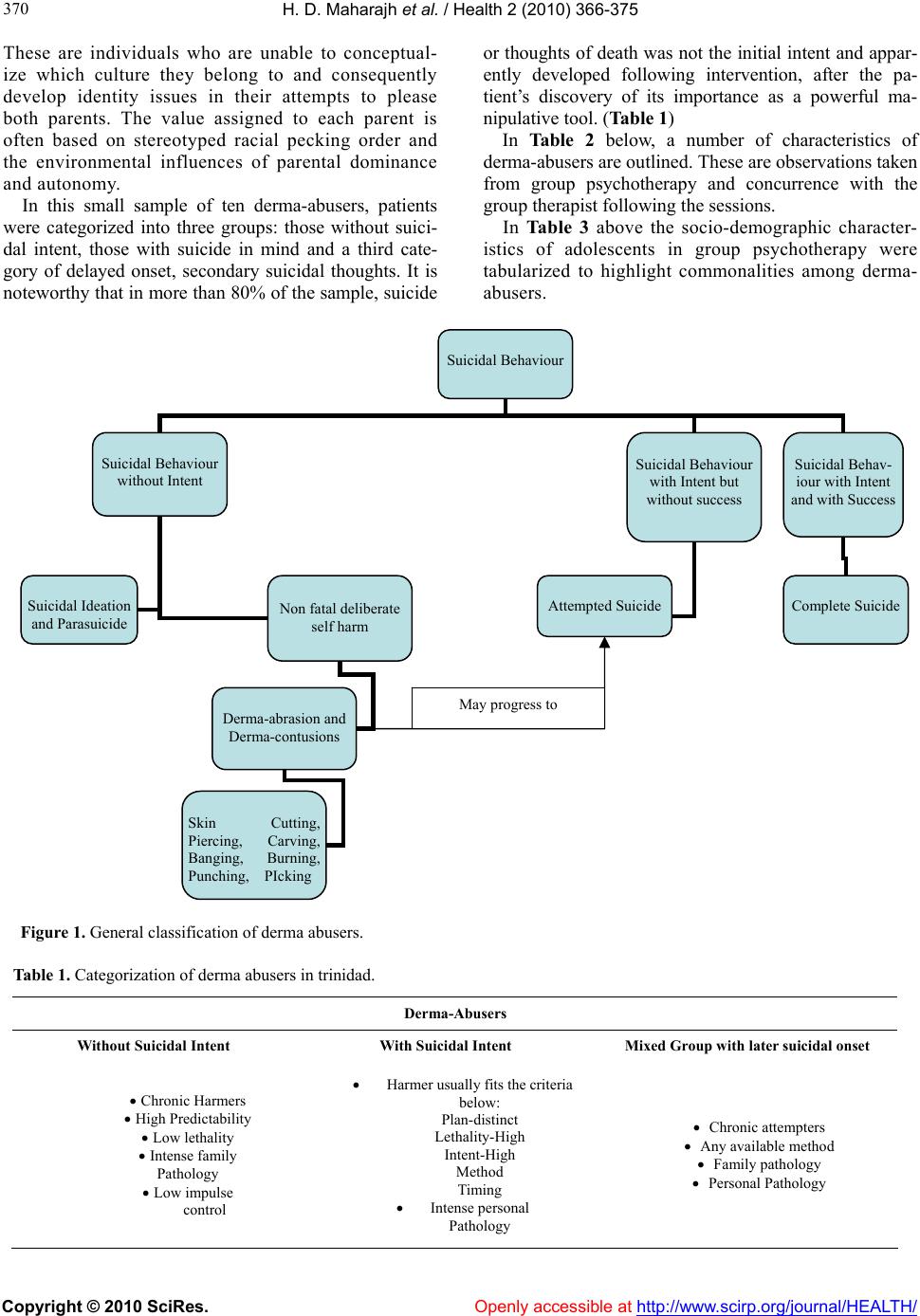

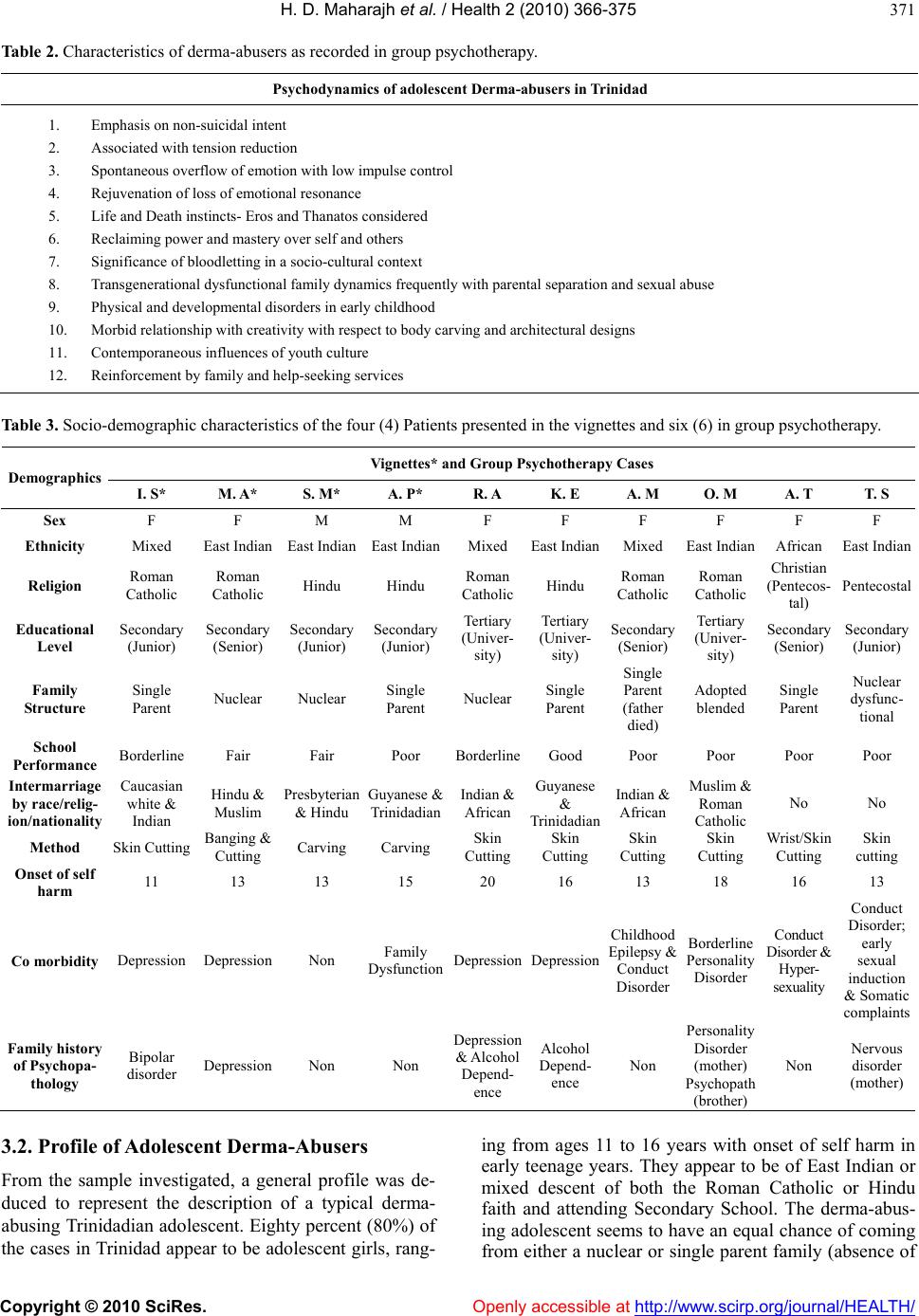

Vol.2, No.4, 366-375 (2010) Health doi:10.4236/health.2010.24055 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ Cutting and other forms of derma-abuse in adolescents Hari D. Maharajh1, Rainah Seepersad2 1Department of Clinical Medicine, University of the West Indies, Trinidad, West Indies; drharim@carib-link.net 2Psychologist, Department of Clinical Medicine, University of the West Indies, Trinidad, West Indies; rainahs@hotmail.com Received 22 November 2009; revised 25 December 2009; accepted 28 December 2009. ABSTRACT Cutting or self inflicted epidermal damage (derma-abuse) describes a number of blood- letting behaviours among adolescents. Unlike suicidal behaviour, it is associated with low le- thality and the absence of suicid al attempt s. The purpose of this study is two-fold: Firstly, to present and discuss vignettes of four young adolescents and secondly, to study the dynam- ics and characteristics of six derma-abusers who have attended Dual Group Therapy (DGT) concurrently with their parents for a six month period. Our findings suggest that patients in- volved in derma-abuse are generally non-sui- cidal but engage in comfort cutting for the psychological release of pain, tension reduction and anger management. There is a preponder- ance of females (80%) with an over-representa- tion of mixed origin and borderline cultural states. In this small group, males amounted to 20% and were more bizarre, gruesome and bru- tal in their self-abuse. Of the total sample, 10% were of African origin, 60% were of Indian de- scent and 30% were of mixed ancestry. Psy- chodynamic factors explored in Dual Group Therapy (DGT) are the emphasis on non-suici- dal intent, association with tension reduction, reclaiming power and mastery over self and others, life and death instincts, the significance of bloodletting in a socio-cultural context, trans - generational conflicts, dysfunctional family dy- namics frequently with parental separation and sexual abuse and early sexual induction. Keywords: Derma-Abuse; Cutting, Self-Harm; Adolescents; Non-Suicidal Intent 1. INTRODUCTION Self-inflicted epidermal damage, referred to as derma- abrasion and derma-contusion are common practices among young adolescents. There is much confusion in the classification of su icidal behaviours with the general view that self-inflicted human blood release is equated to suicidal behaviour. The literature is replete with de scrip- tive terminologies: Suicide and parasuicide [1] suicide and deliberate self poisoning/injury [2], and Non-fatal deliberate self-harm [3]. Other synonyms are “self in- jury” (SI), “self-harm” (SH) “self-mutilation,” “deliber- ate self-harm”, (DSH) “self injurious behaviour” (SIB), and “self inflicted violence” (SIV) which are used inter- changeably to explain common patterns of behaviour where demonstrable injury is self inflicted [4-9]. Self-mutilation has its origin in many cultures around the world. In ancient Mayan civilizations, Sadhus or Hindu ascetics and early Catholic and Jewish Canaanite rituals, all involved some form of bloodletting or self flagellation that are associated with great religious and spiritual sacrifice or rites of passage [10]. In the 1880’s, this form of behaviour was the norm among cultures and was not distinguished from other behavioural problems. In 1935 and 1938, an important distinction was made with a modification of the term self-mutilation that was initially introduced by L. E Emerson [10]. This differen- tiation considered the view that suicidal behaviour and self-mutilation were two separate entities. As Menninger stated in his book “self-mutilation was a non-fatal ex- pression of an att e nuat ed death wish” [10]. Internationally, the most common form of clinically determined self-harm is skin cutting. This occurs in 70% of the individuals that harm themselves, followed by the act of banging or hitting oneself (21% to 44%) and lastly 15% to 35% of persons who engage in acts of burning themselves [11,12]. In non-clinical popula- tions such as college samples, the most common form of self-injurious behaviour was severe forms of scratch- ing and pinching which results in bleeding and scarring (51.6%). This was followed by acts of hitting objects to the point of blood release (37.6%), then cutting (33.7%) followed by acts of punching and banging with blood release (24.5%). Body surface areas targeted by self- harmers are the areas that are of easiest access such as arms, hands, wrists, thighs and abdomen [13-15]. However, there seems to be no agreement on findings of deliberate self-harm since similar rates have been re-  H. D. Maharajh et al. / Health 2 (2010) 366-375 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 367 ported in both institutional and community populations. In non-clinical populations, 4% of the adult population had engaged in deliberate self-harm with a similar find- ing of 4% in military recruits, (33). College populations as a rule have reported higher rates of DSH, ranging from 14%-38% [4,12,16,17]. In Europe, for persons over the age of fifteen (15), there is an average rate of 0.14% for males and 0.19% for females [18]. In the local setting, self-harm has been on a steady rise over the past decade. A conservative estimate of the incidence rate of students referred to a psychiatric clinic is about 0.5% percent of secondary school students in Trinidad. Approximately four cases per month are re- ported at the Eric Williams Medical Sciences Complex at Mt. Hope with an emphasis on derma-abuse or skin cutting. In comparison to larger countries such as in England 6.9% of students’ ages 15 and 16 in a cross sec- tional study of 41 schools reported acts of deliberate self-harm, [19]. In 2007, a newspaper report on ‘cutting’ among girls in Trinidad sparked the issue of a mental health crisis [20]. Further, two recent surveys conducted on non- clinical populations have revealed high rates of self- harmers. In a sample of 215 students at the University of the West Indies, the overall prevalence of self-harmers was found to be 24.2 percen t with 9.3 p ercent notated as recent self-harmers and 14.9 percent engaged in self- harming behaviour over the past year [21]. Among the students reporting recent (within the past twelve months) self-harm, the most frequently utilized methods were cutting (70%), sticking oneself with sharp objects (50%), and scratching oneself (45%). Students invariably util- ized multiple forms of derma-abuse. Analysis of the self-harmers over a one year period revealed that those who reported recent self-harm be- haviour had an average of seven times as many (M = 35.6 s.d = 54) incidents than those with a past history of self-harm behaviour. In another study of 174 students, [22] there was an overall prevalence rate of 31.6 percent with a history of self-harm. In terms of recent self-harm 11.5 percent indicated this in comparison to 20.1 percent who engaged in self-harm behaviour more than a year ago. Within this sample 8.6 percent reported cutting, 8.6 percent indicated severe scratching and 6.9 percent, nee- dle sticking. Of interest, 9.2 percent admitted to con- suming pills, consumption of excessive amounts of al- cohol, hair pulling (trichotillomania) and food refusal, [22]. An interesting find ing is that although these studies were conducted at the same University in Trinidad dur- ing the same year, differential rates of 31.6% [22] and 24.2% [21] were recorded for self-harm behaviours. It is evident that many researchers have described a medley of behaviours that have been categorized as life threatening and equated with suicidal intent. While some authorities [19,23,24] have commented on the low lethal- ity of derma-abusers, the boundaries appear to be blurred. The purpose of this study therefore is two- fold: Firstly, to present and discuss vignettes of four young adolescents and secondly to study the dynamics and characteristics of six derma-abusers who have attended group psychotherapy for a six-month period with em- phasis on their suicidality and treatment. 1.1. Theories of Self Harm There are many explanatory models of self-harm that en- compass various theories in psychology. Self-harm has been described through Behavioral and Systems theories, Psychodynamic and Psychoanalytical models as well as Interpersonal and Object relations approaches [25,26]. Behavioral and Environmental models theorized that self-mutilation creates internal or environmental re- sponses that are reinforcing to the individual. The Drive models purport a psychoanalytical understanding of the self-harm behavior, specifically with the Anti-suicide and Sexual model. The Anti-Suicide model claims that self-mutilation is a suicide replacement, an attempt to avoid suicide, a compromise between life and death drives, and a sort of ‘microsuicide.’ The Sexual model states that self-mutilation stems from conflicts over sexuality, sexual development, masturbation, menarche and menstruation [25,26]. The Affect Regulation Models offer a psychodynamic explanation through the affect regulation model and the dissociation model. Th e Affect Regulation model claims self-mutilation stems from the need to express or control anger, anxiety, or pain that cannot be expressed verbally or through other means whereas the dissociation model states that self-mutilation is a way to end or cope with the effects of dissociation that results from the intensity of affect. Many self-harmers report that they want to feel alive again and acts such as skin cutting removes their feelings of numbness [25,26]. The Boundaries Model which builds it explanatory power on interpersonal and object relations theories state that self-mutilation is an attempt to create a distinction between self and others. It creates boundaries or an iden- tity to protect against feelings of being engulfed, on the other hand a fear of loss of identity. It reinforces self- mutilation as evidence of familial or environmental dys- function [25,26]. 1.2. Objective In this clinical study, prefaced with a comprehensive review of the local and international literature, four vi- gnettes and six patients and their families in Dual Group Therapy (DGT) are studied over a six month period. The purpose is to define socio-demographics characteristics and to understand the dynamics of derma-abusers in the context of interpersonal, trans-generational and envi- ronmental factors. An appropriate management strategy is devised.  H. D. Maharajh et al. / Health 2 (2010) 366-375 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 368 2. RESULTS 2.1. Vignette 1 I. S. is a 13 year old female student, of Caucasian de- scent, who resides in Singapore. She was born in Flor- ida, of mixed origin and of the Roman Catholic faith. She came to Trinidad for treatment since she could not be contained in Singapore. She has Trinidadian roots as most of her family is originally from the island. The patient has been reportedly skin-cutting since 2007 when she was eleven years old. She reported that she had accidentally cut herself with a broken tea cup during one of the many arguments of her parents. She further stated that her ‘accidental injury’ had allevi- ated her emotional confusion and made her feel re- laxed. In 2008, she was hospitalized for a two (2) week period after a cutting incident while in Singa- pore. On her release, it was discovered that she smug- gled a piece of glass into the hospital by concealing it in her clothing and had continued cutting herself on her thighs and was further warded at the facility. In July, in Trinidad, she became so distraught and tense, she begged her Aunt who was visiting from Florida to allow her ‘to make just a little nick on her wrist to alleviate her confusion’. Her most recent episode was in September 2009. She presented for cutting her left wrist at the Health Facility and subsequently taken to the University Hospital and warded at the Paediatric Ward. The patient with a history of skin cutting and burning indicated her most recent cutting was not a suicidal attempt but was used to eliminate stressors in her life, inclusive of a strained relationship with her cousins. In a review of her developmental, personal and family history she has had somewhat of a tumul- tuous past from an early age. As a toddler, she exhib- ited temper tantrums at age 3, her parents divorced when she was age five (5), and she reported that her mother has been in abusive relationships, not only with her father, resulting in her having to move be- tween Malaysia and Singapore. Her developmental milestones were normal but early visits to her Paediatrician had shown evidence of pre- cocious development. At a routine pediatric checkup at age 6, the patient was noted to have a unilateral breast bud and pubic hair. The pediatrician referred her to an Endocrinologist where FSH, LF and other hormonal levels testing were done. They were all within normal range. A bone age scan was also done which showed that the age of her bones were consistent with her chronological age. Subsequently, a unilateral ovarian cyst was discovered via ultrasound. This was monitored for six months and at the second ultrasound no cysts were found. The endocrinologist has since discon- firmed precocious development despite her advanced sexual development. In Trinidad, brain scans CT and MRI were found to be normal as well as Electroen- cephalographic (EEG) studies. In her personal history, she has shied away from her usual extracurricular activities such as netball, football and swimming when she started cutting. Her attempts to conceal the scars have resulted in her lack of interest in other activities but she still con tin ued in th e school ch oir. I.S. described herself as always being below average, and always had difficulty concentrating since very young expressing that she has always been taken long periods to complete assignments. She has never got into any physical fights at school or otherwise. Her history of friendships has been mixed with some “bad” friendships, but presently she has trustworthy friends. She lives with her mother, her mother’s fiancée and his children and will be returning to Singapore soon. Her maternal aunts and mother are being treated for depression. 2.2. Vignette 2 M. A is a 16 year old female student of East Indian de- scent who resides in Trinidad. She is the youngest of three children. She presented on this occasion with in- gestion of six (6) Painol tablets and two (2) painkillers. The incident occurred in August 2009 and was precipi- tated by an argument with her current boyfriend who is eight years older and a friend of her brother. She de- scribed herself as feeling depressed, hopeless and frus- trated, with loss of interest in activities. She normally enjoyed listening to music and watching television, but did not have any intent to die. After this incident, she reported feelings of sadness for long periods over the next two days. M. A has a prior history of skin cutting which had started two years ago. Her first incidence of skin cutting was in early Form 3 (age 13). She described feeling angry but cannot re- member the details of the incident. She also stated that she engaged in banging her fists against the walls in her bedroom when she felt upset and frustrated due to argu- ments with her parents surrounding incidents with her boyfriend. Both her parents’ family has a history of depression. Her father’s two cousins have depression and one of her mother’s brothers has been committed to a mental institution following a nervous breakdown. One has also committed suicide. The patient herself has also been treated for depression on her initial visits to the psychiatrist. Her developmental history was insignificant as de- velopmental milestones were reported in congruence with her age. She began puberty at around age twelve (12). She has had no major accidents or illn ess to requ ire hospitalizations. She has visited a psychologist fo r a few sessions after she broke school on the first occasion. Her relationship with her parents and brother has been somewhat average since the incidents occurred but  H. D. Maharajh et al. / Health 2 (2010) 366-375 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 369 presently the family ties are improving. In terms of her personal history, M. A has reported to having two previous relationships from the age of 12 which lasted two (2) months, and then at age 13 with a twenty one (21) year old man, which lasted one (1) year and eight (8) months. M. A’s current boyfriend is twenty five (25) and this relationship developed as she enjoyed conversing with him as well as being a family friend. She expressed that she enjoys school very much and gets along with everyone including her friends. She has no history of aggressive behavior. Her performance in school is fair, but her grades have been falling due to her involvement with her boyfriend. Both her parents family have a history of depression. Her father’s two cousins have depression and her mother’s family has depression. One of her mother’s brother has been committed to a mental institution fol- lowing a nervous breakdown and one committed suicid e. The patient herself has also been treated for depression on her initial visits to the psychiatrist. 2.3. Vignette 3 S. M is a fourteen year old Secondary School student who was referred to the Psychiatric Services for self- harm, following a self infl icted t att oo whi ch he carved on hi s l e ft arm with a symbol of his initial S. He did this without the permission of his parents because “he wanted to feel pai n”. He mutilated his forearm with a razor blade and covered it with ink in order to ma ke a tattoo. In addition, the school guard found letters in his pos- session written in blood and ink which were messages of hate. He stuck a fountain pen into the v a in of his forearm thereby withdrawing blood and wrote a letter to his al- leged girlfri e n d. In his past history, at the age of five years on a school excursion he was separated from the class and claimed that people stamped on his chest. He was found by two strangers who carried him back to school. At the age of nine years, he received electric shocks from open wires with no serious injuries. It is not known whether these were accidental. Both his parents are alive and he will drink with them on special occasions and will even smoke cigarettes. He has no sexual relationship but claims that he has many girlfriends, defining a girlfriend as “someone to be with when feeling down.” At the age of fourteen, he suffered a fracture of the radius due to a fight at school. He was close to his grandfather who recen tly died. On interview, he was properly groomed adequately clothed with a relaxed behavior. His affect was appropri- ate and speech fluent. He said he did not believe in God. He gave no reasons for his behavior and appeared to be smug about it. 2.4. Vignette 4 A. P is a thirteen (13) year old male Form 3 secondary school student of Indo-Guyanese descent. He was re- ferred by the school guidance officer with a two month history of carving a tattoo on his left forearm with the inscription ‘Sasha’ his girlfriend. He painted it with ink creating a self- made tattoo. His mother reported that he is aggressive at home, stealing jewelry and money al- legedly giving it to his girlfriend. He spends a consid- erably amount of time at night speaking to the girl on the phone which his mother attributes to his poor perform- ance at school. He was born in Guyana and was kept at the hospital for an extra week due to an infection. His developmen- tal milestones were normal but his mother noted that he is extremely short tempered and responds with rage at the slightest provocation. He is the last of three (3) sib- lings with an older sister and brother. He does not get along with his brother and recently pulled a knife at him. He came to Trinidad six (6) years ago with his mother, who has been separated from his father for nine (9) years. Presently he lives with his grandmother, grandfather and brother aged seventeen (17). His mother is now in a sec- ond relationship with a new husband for the past eight (8) years. A. P does not get along with his stepfather and accuses him of stealing the lost money and jewels. All members of his family except his stepfather are of Guy- anese origin. He denies the use of tobacco, alcohol and drugs. He was diagnosed as having an impulse control disorder in his first contact with the psychiatric services on the island. With respect to his derma-abuse, he feels no pain on carving and is supported by his girlfriend who is ex- tremely thrilled at his show of love. His mother has con- tacted her on this issue and she has denied receiving money and stolen rings from him but is adamant that no one can stop him from seeing her. 3. ANALYSIS OF STUDIED GROUP 3.1. General Classification of Suicidal Behavior with and without Intent In the figure below, a classification based on a small sample of ten (10) derma-abusers is presented. Pa- tients involved in derma-abuse are generally non sui- cidal but engage in comfort cutting for the psycho- logical release of pain, tension reduction and anger management. In this small group, males amounted to 20% and were more bizarre, gruesome and brutal in their self-abuse. Females accounted for the major- ity of the sample (80%) and among these; approxi- mately 38% were of mixed origin. Of the total sample 10% were of African origin, 60% were of Indian de- scent and 30% were of mixed ancestry. The high percentage of abusers of mixed origin was unex- pected and a plausible explanation is that these ado- lescents find themselves in a borderline cultural state.  H. D. Maharajh et al. / Health 2 (2010) 366-375 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 370 These are individuals who are unable to conceptual- ize which culture they belong to and consequently develop identity issues in their attempts to please both parents. The value assigned to each parent is often based on stereotyped racial pecking order and the environmental influences of parental dominance and autonomy. In this small sample of ten derma-abusers, patients were categorized into three groups: those without suici- dal intent, those with suicide in mind and a third cate- gory of delayed onset, secondary suicidal thoughts. It is noteworthy that in more than 80% of the sample, suicide or thoughts of death was not the initial inten t and appar- ently developed following intervention, after the pa- tient’s discovery of its importance as a powerful ma- nipulative tool. (Table 1) In Table 2 below, a number of characteristics of derma-abusers are outlined. These are observations taken from group psychotherapy and concurrence with the group therapist following the sessions. In Table 3 above the socio-demographic character- istics of adolescents in group psychotherapy were tabularized to highlight commonalities among derma- abusers. Figure 1. General classification of derma abusers. Table 1. Categorization of derma abusers in trinidad. Derma-Abusers Without Suicidal Intent With Suicidal Intent Mixed Group with later su ic id al o nset Chronic Harmers High Predictability Low lethality Intense family Pathology Low impulse control Harmer usually fits the criteria below: Plan-distinct Lethality-High Intent-High Method Timing Intense personal Pathology Chronic attempters Any available method Family pathology Personal Pathology Suicidal Behaviour Suicidal Behaviour without Intent Suicidal Behaviour with Intent but without success Suicidal Behav- iour with Intent and with Success Suicidal Ideation and Parasuicide Non fatal deliberate self harm Attempted Suicide Complete Suicide Derma-abrasion and Derma-contusions Skin Cutting, Piercing, Carving, Banging, Burning, Punching, PIcking May progress to  H. D. Maharajh et al. / Health 2 (2010) 366-375 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 371 Table 2. Characteristics of derma-abusers as recorded in group psychotherapy. Psychodynamics of adolescent Derma-abusers in Trinidad 1. Emphasis on non-su ici dal in ten t 2. Associated with tension reduction 3. Spontaneous overflow of emotion with low impulse control 4. Rejuvenation of loss of emotional resonance 5. Life and Death instincts- Eros and Thanatos considered 6. Reclaiming power and m astery over self and others 7. Significance of blood le tti ng i n a s oci o-cultural context 8. Transgenerational dysfunctional family dynamics frequently with parental separation and sexual abuse 9. Physical and developmental disor ders in early childhood 10. Morbid relationship with creativity with respect to body carving and architectural designs 11. Conte mporaneous influences of y outh c ulture 12. Reinforcement by family and help-seeking services Table 3. Socio-demographic characteristics of the four (4) Patients presented in the vignettes and six (6) in group psychotherapy. Vignettes* and Group Psychotherapy Cases Demographics I. S* M. A* S. M* A. P* R. A K. E A. M O. M A. T T. S Sex F F M M F F F F F F Ethnicity Mixed East Indian East Indian East IndianMixed East IndianMixed East Indian African East Indian Religion Roman Catholic Roman Catholic Hindu Hindu Roman Catholic Hindu Roman Catholic Roman Catholic Christian (Pentecos- tal) Pentecostal Educational Level Secondary (Junior) Secondary (Senior) Secondary (Junior) Secondary (Junior) Tertiary (Univer- sity) Tertiary (Univer- sity) Secondary (Senior) Tertiary (Univer- sity) Secondary (Senior) Secondary (Junior) Family Structure Single Parent Nuclear Nuclear Single Parent Nuclear Single Parent Single Parent (father died) Adopted blended Single Parent Nuclear dysfunc- tional School Performance Borderline Fair Fair Poor BorderlineGood Poor Poor Poor Poor Intermarriage by race/relig- ion/nationality Caucasian white & Indian Hindu & Muslim Presbyterian & Hindu Guyanese & Trinidadian Indian & African Guyanese & Trinidadian Indian & African Muslim & Roman Catholic No No Method Skin Cutting Banging & Cutting Carving Carving Skin Cutting Skin Cutting Skin Cutting Skin Cutting Wrist/Skin Cutting Skin cutting Onset of self harm 11 13 13 15 20 16 13 18 16 13 Co morbidity Depression Depression Non Family Dysfunction Depression Depression Childhood Epilepsy & Conduct Disorder Borderline Personality Disorder Conduct Disorder & Hyper- sexuality Conduct Disorder; early sexual induction & Somatic complaints Family history of Psychopa- thology Bipolar disorder Depression Non Non Depression & Alcohol Depend- ence Alcohol Depend- ence Non Personality Disorder (mother) Psychopath (brother) Non Nervous disorder (mother) 3.2. Profile of Adolescent Derma-Abusers From the sample investigated, a general profile was de- duced to represent the description of a typical derma- abusing Trinidadian adolescent. Eighty percent (80%) of the cases in Trinidad appear to be adolescent girls, rang- ing from ages 11 to 16 years with onset of self harm in early teenage years. They appear to be of East Indian or mixed descent of both the Roman Catholic or Hindu faith and attending Secondary School. The derma-abus- ing adolescent seems to have an equal chance of coming from either a nuclear or single parent family (absence of  H. D. Maharajh et al. / Health 2 (2010) 366-375 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 372 father figure), though, within the nuclear family there is usually a dominant parent, the mother. Their family background seems to be of mixed origin, either by relig- ion, race or nationality and there is a history of family dysfunction and instability. Their performance at school spans the poor to borderline ranges and the individual is usually diagnosed with a depressiv e disorder due to rela- tional conflicts. In some cases there is a history of Con- duct Disorder in childhood. Associated psychosocial factors are low self-esteem, body image and identity disturbances and early cour tsh ip and sexual induction. This is on a background of Trini- dad and Tobago having the second highest rate of suicide in the Caribbean region and may be a precursor for such behaviour in adulthood. Different forms of derma-abra- sion and derma-contusion observed among the sample were skin cutting, banging, scraping, carving, burning and branding, picking at the skin and removal of blood with instruments (pen and needles). Skin cutting was more prevalent amongst the female sample and carving with tattooing was present in all the male derma-contu- sion cases. It seems the intensity of the latter paints a more bravado picture of sacrifice to a loved object when compared to skin cutting by the females. Sexual drives are a major operative factor in both male and female derma- abusers. 4. DISCUSSIONS An examination of the four (4) vignettes and six (6) cases treated in Dual Group Therapy (DGT) highlights significant commonalities in the life histories and pre- senting concerns of all patients. The vignettes and group psychotherapy cases presented are of adolescent indi- viduals who began self-harm between the ages of 11 to 20, with a mean of 14.8 years and 80% between the 11-16 age group. According to the literature, studies have reinforced that individuals aged 11-25 have been known to self-injure [27]. Eighty percent (80%) of the cases discussed here were children of intermarriages by race, religion or nationality. It raises the issue of identity confusion and misunder- standing of culture and practice as it starts at the family level. The author is of the opinion that these individuals suffer from a borderline cultural state which results in their poor conceptualization of which culture they be- long to. This cultu ral confusion in ethnicity, religion and nationality is often stratified by the environment in which one lives and can result in identity splitting and confusion. In psychodynamic terms, blood- letting can be viewed as an individual attempt to remove the bad blood or bile of their mixtures in a purging process. Durkheim’s theories of anomie, egoistical and altruistic behaviors and Erikson’s stages of development are ap- plicable here. On closer inspection, the precipitating cause of self- harm is strongly associated with the establishment of early relationships with sexual induction as evid enced by 70% of the cases. This holds commonalities as those purported by the Sexual Model of self-mutilation. Among the teenage population, sexual experimentation and risk taking behavior is a common aspect of this age group. With numerous coping strategies to aid in the tension reduction n eed ed, caused by volatile p artnersh ip s, derma-contusions seemed to be prevalent. Within the present sample of self-harmers skin cutting was ob- served in all of the females and carving, being the derma-contusion of choice among the male cases. It seems the intensity of the latter paints a more bravado picture matching the male image, in comparison to ‘skin cutting’ portraying a slightly less gruesome, ‘romantic’ sacrifice. Though two different forms, both make the assumption of the ultimate sacrifice, bloodshed. The cases presented underlie the occurrence of trans- generational dysfunctional family dynamics as shown in Table 3. Approximately 60% of cases report family separation, divorce, transcultural differences and family psychopathology. In the nuclear family there was in- variably the presence of a dominant parent which served as a major stressor in the individuals’ life. In addition, there were high rates of psychiatric disturbances (80%) and psychosocial difficulties (100%), especially the prominence of mood disorders (40%) in individuals who self-harm within the present sample, as reported by pre- vious studies [28]. It is likely that a substantive propor- tion of these patients will progress to Bipolar disease. Aggressive tendencies, emotional disorders, temper tan- trums, conduct disorders and teenage angst were preva- lent. The aggregate of emotions that are expected of this age group coupled by intense family psychopathology as expressed by 60% of the sample and personal psycho- pathology as indicated by 90% of the cases seem to be antecedents of self-harming behavior. Most of the indi- viduals in the vignettes and group therapy cases have stated that they use these behaviors as a way of express- ing anger and frustration when emotions are at a high and the overflow is unbearable, whereas some individu- als self-harm to prevent suicide, or escape unwanted feelings, as indicated by the Anti Suicide Model [25,26]. As expressed by Vignette 2, she was unable to explain the situations surrounding her first skin cutting episode but was certain of the fact that she was extremely over- whelmed by anger. Since banging her fists on the wall ceased to work anymore, she upped the ante to a more punitive method that she felt helped at stressful times. In a recent interview with M.A she stated that she was faced with a situation concerning an assignment, in which she had to redo a portion that she assumed was finished. She reported that for a brief moment she thought of cutting but reconsidered her actions. M.A’s behavior seemed to hold commonalities to the Affect Regulation Model of self-mutilation as she was over- whelmed by emotion. The extent of the behaviors and  H. D. Maharajh et al. / Health 2 (2010) 366-375 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 373 meaning of their acts are unknown to them and are often given interpretative credence in treatment. Also, their behavior is significantly different from suicidal behavior with intent as the individuals in these cases have made their scars public. As suggested by Hawton [29] self harm behavior is distinctly suicidal if the act is “planned for, carried out and followed through in such a way as to keep it from the notice of others.” Even though derma- abusers may try to hide th eir wounds the target areas are easily noticeable despite concealment with hand bands or clothing. The new found control that has been indicated by some of the above cases and vignettes has been the main function of the deliberate derma-contusions that are self- inflicted. It may be apparent that the manifestation of family psychopathology and family strife is showing itself in adolescence as creative forms of ‘bloodletting’ as it parallels Hippocrates early assumptions of ‘purging of bad humors.’ [30]. Seventy five percent of the cases report their bloodletting as an addiction that they desper- ately need to engage in with the likes of alcohol and drugs. It seems that a derma-contusion returns it users to an equilibrium state that is required for their existence. This supports the underlying commonality among the cases with the lack of suicidal intent. They perceive their self-harming behavior as a form of rejuvenation by let- ting the bad blood out rather than as a destruction of body tissue. An important observation is the predictability and chronicity of the self-harming behavior without suicidal intent. In most of the vignettes derma-abusers repeated these behaviors as certain events presented in their lives, indicative of maladaptive coping mechanisms as well as a need to remedy the situation at the moment, suggestiv e of perhaps a hopeful future. An emphasis here can be placed on a compromise being made between life and death instincts of psychoanalytical theory, specifically the Anti Suicide Model. They derive pleasure not from stereotypical pleasurable behaviors but rather from ag- gressive, self punitive behaviors that widens the power differential between themselves and others. In an effort to heal, they set themselves apart from normal methods of remedy, lending resemblance to the Boundaries model of self-mutilation. In Vignette 4, A. P felt that he was showing his commitment to his cause when he carved the name of his girlfriend along his forearm. He seemed to be giving of himself wholly in a way he probably could not express in words as proffered by the Affect Regulation Model of self-mutilation [25,26]. The excessive compulsion and obsessive psychologi- cal dependence of derma-abusers seems to be cognizant of its chronicity a mong the individu als inflicted with the addiction. Fifty percent of them seem to experiment with different methods of self-harm before the addiction of the tool of choice develops. It seems though, when in desperation the tool of choice may best be substituted with an available option . As illustrated by Vignette 1, I.S went to great lengths to conceal a piece of glass within her clothing, and thought nothing of it as she continued to deliberately harm herself at the hospital, even though she found comfort using razorblades. Prior evidence of this kind of dependent behaviour can also be seen where she begged a relative to allow her to cut her wrist in an attempt to equilibrate herself again. In this study, derma-abusers were not generally in- volved in acts with suicidal intent (Figure 1, Ta b le 1). The ten patients were categorized into three groups, those without suicidal intent, those with suicide in mind and a third category of delayed onset, secondary suicid al thoughts. It is noteworthy that in more than 80% of the sample, suicide or thoughts of death was not the initial intent. These thoughts apparently developed following intervention, on discovery that their behaviors were en- meshed with the feelings o f power and mastery over self and others, effects on tension reduction and as a form of revenge and hostility directed against family members. The act itself became the most powerful manipulative tool reinforced in a Caribbean setting with a history of aggression, violence and more recently high murder rates in Tr inidad (Table 2). The treatment of derma-abusers is difficult and pre- sents a major challenge. After failure of individual ther- apy designed along the lines of Linehan’s Dialectical Behaviour Therapy model (DBT) [31] another method was employed. DBT was unsuccessful for the following reasons: Patients were too young and disturbed to ac- quire what Linehan calls wisemind. With respect to the ‘what’ and ‘how’ skills, they could not focus on mind- fulness. They could not develop interpersonal effective- ness to say no, or resist their urges of cutting and had little distress tolerance and emotional regulation. A novel system of Dual Group Therapy (DGT) was devised. This is the simultaneous occurrence of two group sessions of one and a half hours held concurrently in two adjoining sound proof rooms of the same building once per week. The following screening process was instituted. First the initial interview with the patient and the attendants in the presentation of the problem (30 minutes). In the local setting, it is customary for the en- tire extended family, caretakers and friends to accom- pany the patient. In the second stage, the patient was interviewed individually (45 minutes) being allowed to tell her story and assessing significant others in her life. In the third stage, two significant others, determined by the patient and therapist were asked to be seen together with the patient. In a client centered approach, the dy- namics of interaction of family members and patients were observed. The therapist had to be cautious in not ascribing blame to anyone person, attempting to avoid confrontation and acting-out behavior commonly found in our setting. Information on ethno-historiography, that is, the characteristics of origin, race, culture, religion and  H. D. Maharajh et al. / Health 2 (2010) 366-375 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 374 lifestyle were sought. This socio-cultu ral academic exer- cise presented little threat to those involved. In the final stage, an agreement (non-signed contract) was reached by the parents (caretakers) and the patient to attend two concurrently run groups namely ‘The Adolescent Group’ and ‘The Parent Support Group’. They were asked to attend for a twenty four sessions (six months) period. The third and fourth stages lasted approximately one hour with a total assessment time of two hours. Parents were given the charge of bringing the patients to the groups. Two trained psychologists conducted the groups and met together with two co-therapists who also were in the group and the psychiatrist for weekly review s fol- lowing the meetings. With shared information and emo- tions from both groups, a tailored management approach was devised for each patient introduced within the dy- namics of group therapy. This study investigates derma-abuse in adolescents. However, two other studies done on adults in Trinidad indicate that this practice continues into adult life. In the University sample [21,22], students in the psychology field were more prone to self-harm than those in natural sciences and engineering fields of study. It seemed the trend of cutting and derma abuse has continued into the tertiary level institution and it may be useful to investigate whether these students were derma abusers during their secondary school life, or has the behavioural pattern emerged during their University life. If the former is sug- gested, a reduction in numbers may be expected if early detection plans by appropriate service providers and per- sonnel are put into place at the secondary school level. The cases and vignettes presented are individuals who have used maladaptive coping in an attempt to remove dysfunctional events in their life. The adolescents have challenged the status quo of ‘normal behavior’ in the hope of normalizing their own lives. Their commonal- ities are striking and lend itself to distinct characteriza- tion of the phenomena of derma-abusing in Trinida d. 5. CONCLUSIONS This is a preliminary study that highlights a growing problem among secondary school children in Trinidad. The author works closely with the School Supervision Unit of the Ministry of Education in Trinidad where a number of s tude n ts ar e r efe rr ed by th e Gu idance Officers who are not equipped to deal with the intensity of prob- lems encountered. The behavior of these students are devastating to both fellow students and staff members alike and can undermine the spiritual and moral values of the schools’ discipline. The fact that there is an ele- ment of contagion or copy cat behavior has led many school authorities, especially those of the denomina- tional Christian schools to perceive the problem to be one of demonical possession and it is not unusual to have these students ostracized and referred for exorcism and spiritual healing. In the presentation of this small sample of ten patients, the intention is to demonstrate the similarities of behav- ior, personal and family psychopathology and dynamics. The psychopathology of the individuals and their fami- lies must be emphasized as these may be major precur- sors to their condition. While there is room in any insti- tution for pastoral care and counseling, the presentation of four (4) vignettes and study of the dynamics of six (6) students in group therapy provide a better understanding of these patients and prov ide a psychological framework for treatment. While this paper does not address their outcome in treatment, it is necessary to recognize th at in group therapy, the inclusion of non-derma abusers in groups can lead to the recruitment of deviants. Family involvement is mandatory since disturbed kids invaria- bly come from disturbed families. Notwithstanding the limitations of it being a small, descriptive observational study, it is however the first clinical study of this nature coming out of the Caribbean region. As highlighted in a daily newspaper two years ago as ‘a mental health crisis’ [20], it is understandable that this will be a major public health issue of adoles- cents in the future, especially in Trinidad and Tobago now on the threshold of first world status. The increased attention to derma-abusing cases may be an indication of additional adolescents engaging in the behavior. So too, it can be attributed to the chang- ing attitudes of adolescents in today’s culture as they freely engage in risky behavior. As previously stated [32], service providers may now have a more keen ability to recognize and report derma-abusing behav- ior with a better understanding of the dynamics in- volved. 6. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I wish to thank Dayna Mohammed of the Psychology Department of the University of the West Indies and Katija Khan, Psychologist of University of Hull in England for their useful comments and contribu- tion to this paper. REFERENCES [1] Kreitman, N. (1989) Can Suicide and Parasuicide be prevented? Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 82, 648-652. [2] Kessel, N. and McCulloch, W. (1966) Repeated acts of self harm and self injury. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 59, 89-92. [3] Morgan, H.D., Burns-Cox, C.J., Pocock, H. and Pottle, S. (1975) Deliberate Self-Harm: Clinical and Socio-Eco- nomic Characteristics of 368 Patients. British Journal of Psychiatry, 127, 564-574. [4] Gratz, K.L. (2001) Measurement of deliberate elf harm: Preliminary data on the deliberate Self harm Inventory. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 23, 253-263. [5] Platt, S., Bille-Brahe, U., Kerkhof, A., et al. (1992)  H. D. Maharajh et al. / Health 2 (2010) 366-375 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 375 Parasuicide in Europe: The WHO/EURO multicentre study on parasuicide I. Introduction and preliminary analysis for 1989. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 85, 97-104. [6] Clarke, L. and Whitaker, M. (1998) Self Mutilation: Cul- ture, contexts and nursing responses. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 7, 129-137. [7] Nock, M.K. and Prinstein, M.J. (2005) Contextual fea- tures and behavioural functions of self mutilation among adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 114(1), 140-146. [8] Baral, I., Kora, K., Yuksel, S. and Sezgin, U. (1998) Self mutilating behaviour of sexually abused female adults in Tu r k e y. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 13, 427-437. [9] Brodsky, B.S., Cloitre, M., and Dulit, R.A. (1995) Rela- tionship of dissociation to self mutilation and childhood abuse in borderline personality disorder. American Jour- nal of Psychiatry, 152, 1788-1792. [10] Wikipedia, Self Injury. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Self- injury [11] Briere, J. and Gil, E. (1998) Self Mutilation in a clini- cal and general population samples: Prevalence, cor- relates and functions. American Journal of Orthopsy- chiatry, 68, 609-620. [12] Favazza, A.R. and Conterio, K. (1989) Female habitual self mutilators. Acta Psychiatrica Scand, 79, 283-289. [13] Muehlenkamp, J.J. (2005) Self Injurious behaviour as a separate clinical syndrome. American Journal of Or- thopsychiatry, 75, 324-333. [14] Favazza, A.R. (1996) Bodies under Siege: Self Mutila- tion and Body modification in culture and psychiatry (2nd Edition). John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore. [15] Whitlock, J., Eckenrode, J. and Silverman, D. (2006) Self Injurious behaviours in a college population. Pediatrics, 117, 1939-1948. [16] Favazza, A.R. (1992) Repetitive self mutilation. Psychi- atric Annals, 22, 60-63. [17] Gratz, K.L. (2006) Risk factors for deliberate self harm among female college-students: The role and interaction of childhood maltreatment, emotional inexpressivity, and affect intensity/reactivity. American Journal of Ortho- psychiatry, 76, 238-250. [18] World Health Organization, Euro multicentre study of suicide. http://cebmh.warne.ox.ac.uk/csr/monitoring.html [19] Hawton, K., Rodham, K., Evans, E., and Weatherall, R. (2002) Deliberate self harm in adolescents: Self report survey in schools in England. British Medical Journal, 325, 1207-1211. [20] Castillo, K. (2007) Mental health crisis looms, expert says: Girls cutting themselves. The Trinidad Express. http://www.trinidadexpress.com [21] Mohammed, R. (2008) Deliberate self-harm in a non- clinical population: Emotion and coping strategies. MSc. Thesis, University of the West Indies, St. Augustine. [22] Allum, S. (2008) Risk factors associated with deliberate self-harm. MSc. Thesis, University of the West Indies, St. Augustine. [23] Favazza A. R. (1998) The coming of age of self mutilation. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 186, 259-268. [24] Suyemoto, K.L. (1998) The functions of self mutilation. Clinical Psychology Revi ew, 18, 531-554. [25] Suyemoto, K.L., and Macdonald, M.L. (1995) Self cut- ting in female adolescents. Psychotherapy, 32, 162-171. [26] Messer, J.M. and Fremouw, W.J. (2008) A critical review of explanatory models for self-mutilating behaviors in adolescents. Clinical Psychology Review, 28(1), 162-78. [27] Young people and self harm: A national Inquiry. What do we already know? Prevalence, risk factors and models of intervention. http://selfharmuk.org [28] Harrington, R. and Dyer, E. (1993) Suicide and at- tempted suicide in adolescence. Current Opinion in Psy- chiatry, 6, 467-469. [29] Hawton, K. (1986) Suicide and attempted suicide among children and adolescents. Sage, London. [30] Wikipedia, Bloodletting. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blood letting [31] Linehan, M.M. (1995) Understanding borderline person- ality disorder: The dialectic approach manual. Guilford Press, New York. [32] Cornell Research Program on Self Injurious Behaviour in Adolescents and Young Adults. What do we know about self-injury? http://www.crpsib.com/whatissi.asp |