Paper Menu >>

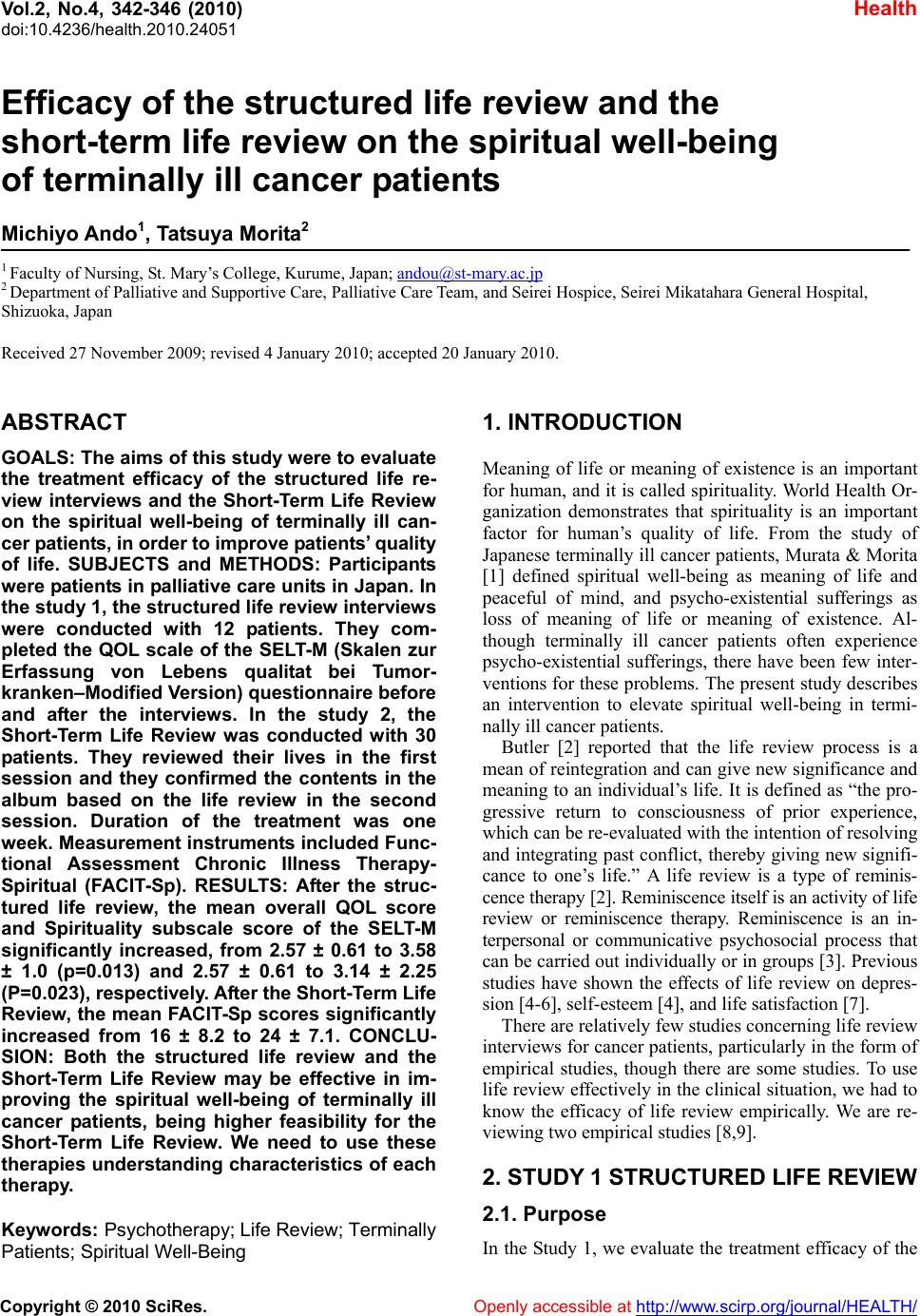

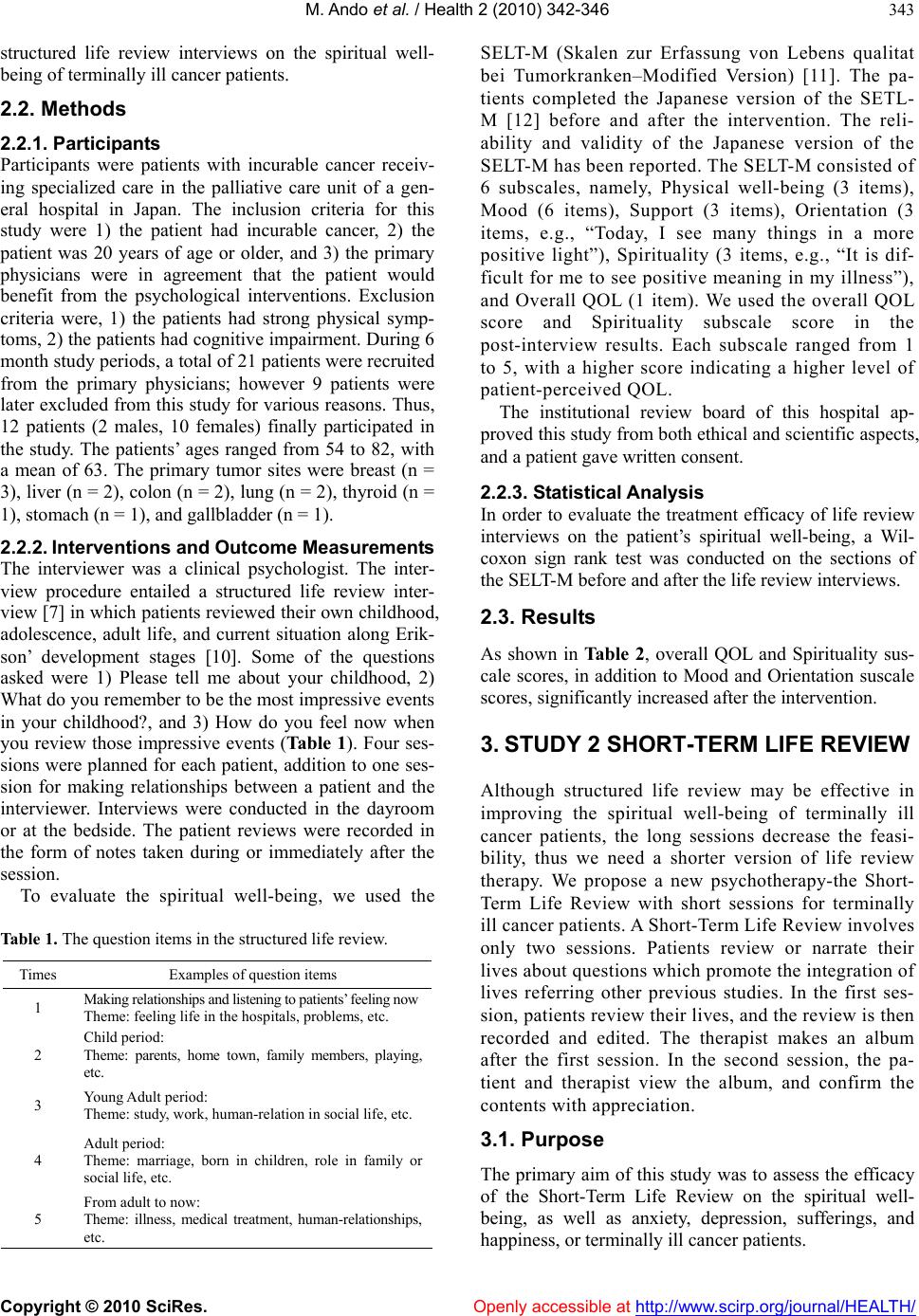

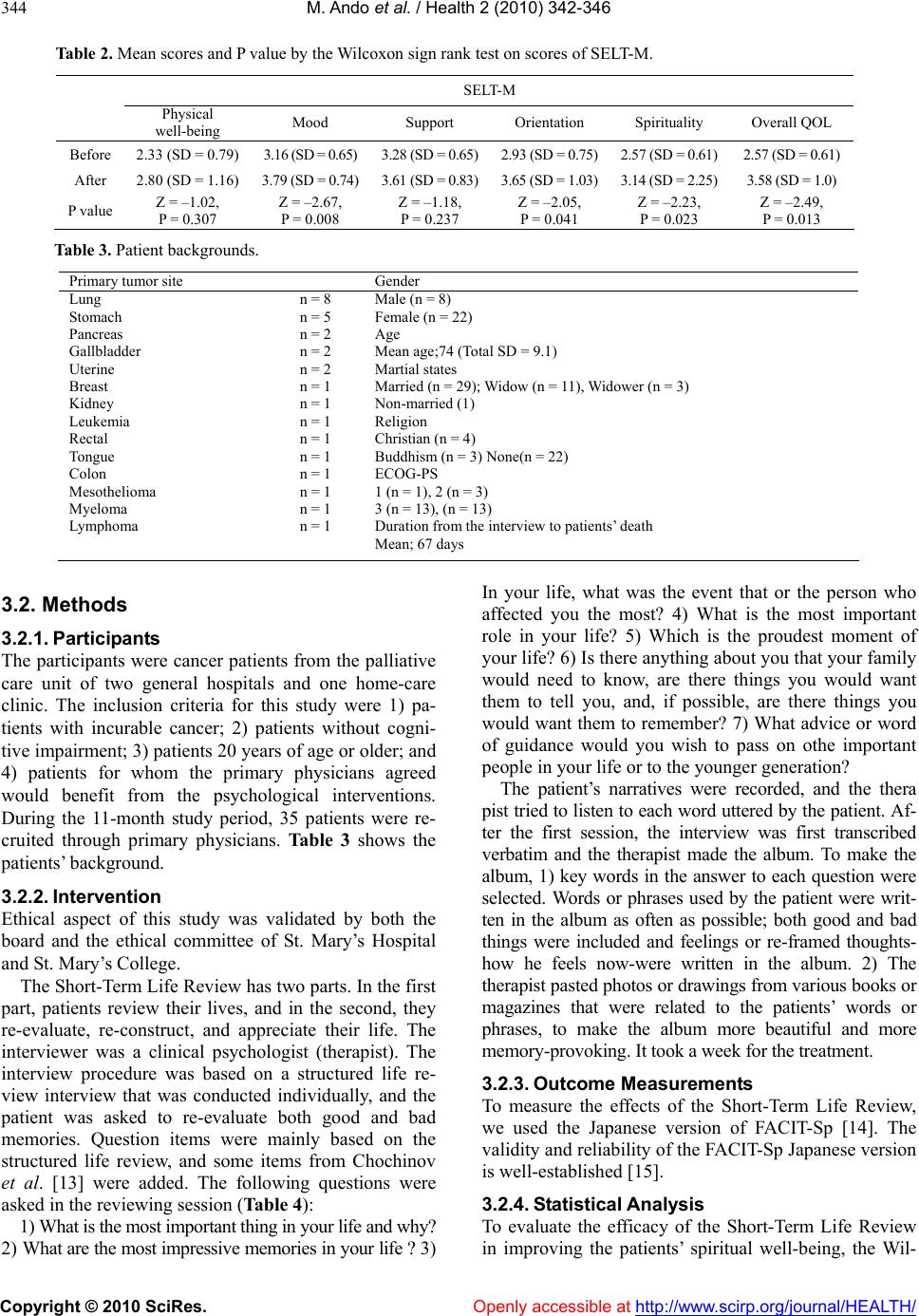

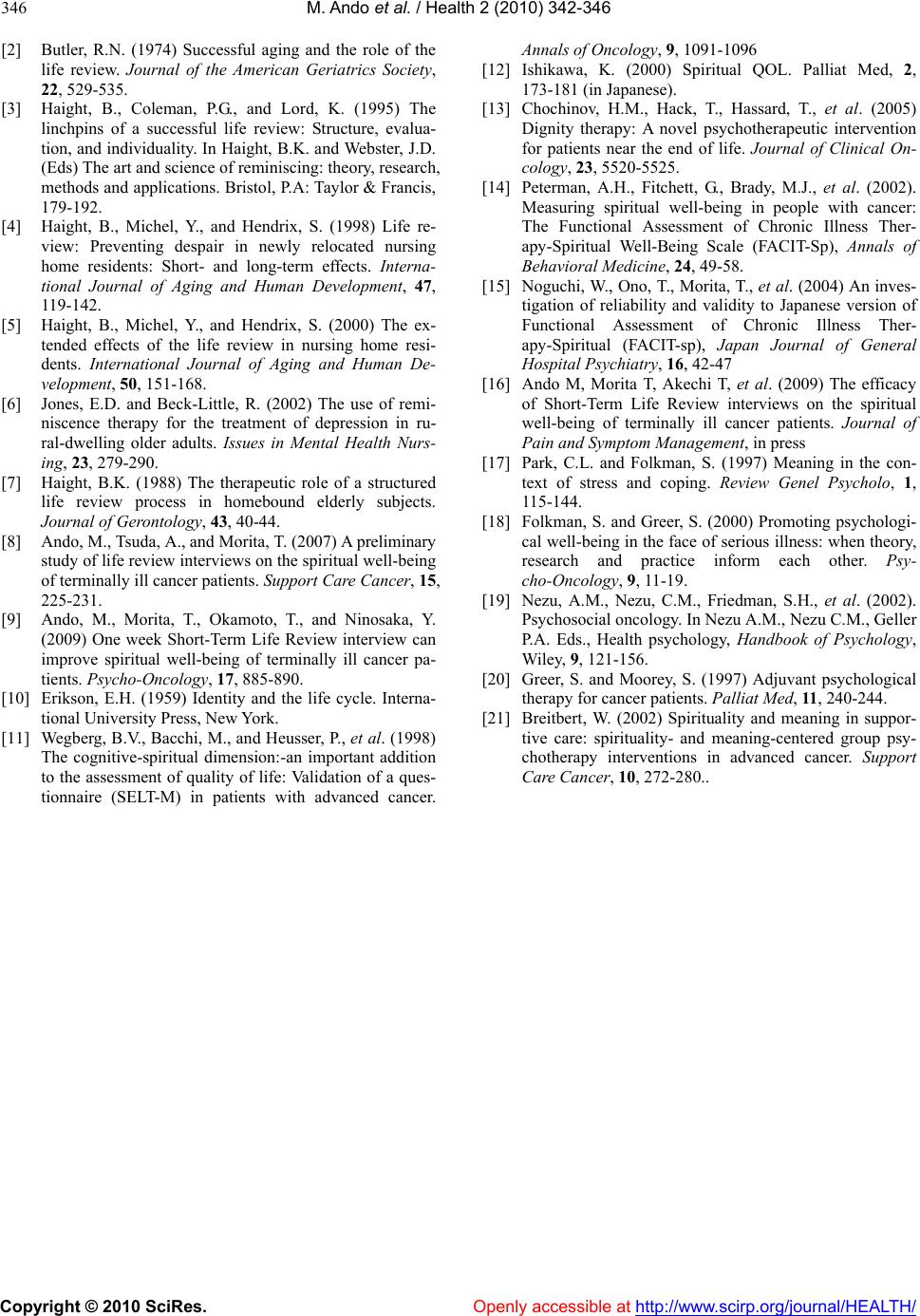

Journal Menu >>

Vol.2, No.4, 342-346 (2010) Health doi:10.4236/health.2010.24051 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ Efficacy of the structured life review and the short-term life review on the spiritual well-being of terminally ill cancer patients Michiyo Ando1, Tatsuya Morita2 1 Faculty of Nursing, St. Mary’s College, Kurume, Japan; andou@st-mary.ac.jp 2 Department of Palliative and Supportive Care, Palliative Care Team, and Seirei Hospice, Seirei Mikatahara General Hospital, Shizuoka, Japan Received 27 November 2009; revised 4 January 2010; accepted 20 January 2010. ABSTRACT GOALS: The aims of this study were to evaluate the treatment efficacy of the structured life re- view interviews and the Short-Term Life Review on the spiritual well-being of terminally ill can- cer p atient s, in order to improv e p atient s’ quality of life. SUBJECTS and METHODS: Participants were patients in palliative care units in Japan. In the study 1, the structured life review interviews were conducted with 12 patients. They com- pleted the QOL scale of the SELT-M (Skalen zur Erfassung von Lebens qualitat bei Tumor- kranken–Modified Version) questionnaire before and after the interviews. In the study 2, the Short-Term Life Review was conducted with 30 patients. They reviewed their lives in the first session and they confirmed the contents in the album based on the life review in the second session. Duration of the treatment was one week. Measurement instruments included Func- tional Assessment Chronic Illness Therapy- Spiritual (FACIT-Sp). RESULTS: After the struc- tured life review, the mean overall QOL score and Spirituality subscale score of the SELT-M significantly increased, from 2.57 ± 0.61 to 3.58 ± 1.0 (p=0.013) and 2.57 ± 0.61 to 3.14 ± 2.25 (P=0.023), respectiv ely. After the Short-Term Life Review, the mean FACIT-Sp scores significantly increased from 16 ± 8.2 to 24 ± 7.1. CONCLU- SION: Both the structured life review and the Short-Term Life Review may be effective in im- proving the spiritual well-being of terminally ill cancer patients, being higher feasibility for the Short-Term Life Review. We need to use these therapies understanding characteristics of each therapy. Keywords: Psychotherapy; Life Review; Terminally Patients; Spiritual Well-Being 1. INTRODUCTION Meaning of life or meaning of existence is an important for human, and it is called spirituality. World Health Or- ganization demonstrates that spirituality is an important factor for human’s quality of life. From the study of Japanese terminally ill cancer patients, Murata & Morita [1] defined spiritual well-being as meaning of life and peaceful of mind, and psycho-existential sufferings as loss of meaning of life or meaning of existence. Al- though terminally ill cancer patients often experience psycho-existential sufferings, there have been few inter- ventions for these problems. The present study describes an intervention to elevate spiritual well-being in termi- nally ill cancer patients. Butler [2] reported that the life review process is a mean of reintegration and can give new significance and meaning to an individual’s life. It is defined as “the pro- gressive return to consciousness of prior experience, which can be re-evaluated with the intentio n of resolving and integrating past conflict, thereby giving new signifi- cance to one’s life.” A life review is a type of reminis- cence therapy [2]. Reminiscence itself is an act ivity of lif e review or reminiscence therapy. Reminiscence is an in- terpersonal or communicative psychosocial process that can be carried out individually or in groups [3]. Previous studies have shown the effects of life review on depres- sion [4-6], self-esteem [4 ], and life satisfaction [7]. There are relatively few studies concerning life review interviews for cancer patients, particularly in the form of empirical studies, though there are some studies. To use life review effectively in the clinical situation, we had to know the efficacy of life review empirically. We are re- viewing two empirical studies [8,9]. 2. STUDY 1 STRUCTURED LIFE REVIEW 2.1. Purpose In the Study 1, we evaluate the treatment efficacy of the  M. Ando et al. / Health 2 (2 010) 342-346 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 343 structured life review interviews on the spiritual well- being of terminally ill cancer patients. 2.2. Methods 2.2.1. Participant s Participants were patients with incurable cancer receiv- ing specialized care in the palliative care unit of a gen- eral hospital in Japan. The inclusion criteria for this study were 1) the patient had incurable cancer, 2) the patient was 20 years of age or older, and 3) the primary physicians were in agreement that the patient would benefit from the psychological interventions. Exclusion criteria were, 1) the patients had strong physical symp- toms, 2) the patients had cognitive impairment. During 6 month study periods, a total of 21 patients were recruited from the primary physicians; however 9 patients were later excluded from this study for various reasons. Thus, 12 patients (2 males, 10 females) finally participated in the study. The patients’ ages ranged from 54 to 82, with a mean of 63. The primary tumor sites were breast (n = 3), liver (n = 2), colon (n = 2), lun g (n = 2), thyroid (n = 1), stomach (n = 1), and gallbladder (n = 1). 2.2.2. Interv entions an d O utcome M ea surements The interviewer was a clinical psychologist. The inter- view procedure entailed a structured life review inter- view [7] in which patients reviewed their own childhood, adolescence, adult life, and current situation along Erik- son’ development stages [10]. Some of the questions asked were 1) Please tell me about your childhood, 2) What do you remember to be th e most impressive ev ents in your childhood?, and 3) How do you feel now when you review those impressive events (Ta ble 1). Four ses- sions were planned for each patient, addition to one ses- sion for making relationships between a patient and the interviewer. Interviews were conducted in the dayroom or at the bedside. The patient reviews were recorded in the form of notes taken during or immediately after the session. To evaluate the spiritual well-being, we used the Table 1. The question items in the structured life review. Times Examples of ques t i o n i t e ms 1 Making relati onshi ps and liste ning t o patients’ feel ing now Theme: feeling life in the hospitals, problems, e tc . 2 Child period: Theme: parents, home town, family members, playing, etc. 3 Young Adult period: Theme: study, work, human-relation in social life, etc. 4 Adult period: Theme: marriage, born in children, role in family or social life, etc. 5 From adult to now: Theme: illness, medical treatment, human-relationships, etc. SELT-M (Skalen zur Erfassung von Lebens qualitat bei Tumorkranken–Modified Version) [11]. The pa- tients completed the Japanese version of the SETL- M [12] before and after the intervention. The reli- ability and validity of the Japanese version of the SELT-M has been reported. The SELT-M consisted of 6 subscales, namely, Physical well-being (3 items), Mood (6 items), Support (3 items), Orientation (3 items, e.g., “Today, I see many things in a more positive light”), Spirituality (3 items, e.g., “It is dif- ficult for me to see positive meaning in my illness”), and Overall QOL (1 item). We used the overall QOL score and Spirituality subscale score in the post-interview results. Each subscale ranged from 1 to 5, with a higher score indicating a higher level of patient-perceived QOL. The institutional review board of this hospital ap- proved this study from both ethical and scientific aspects, and a patient gave written consent. 2.2.3. Statisti cal Analysis In order to evaluate the treatment efficacy of life review interviews on the patient’s spiritual well-being, a Wil- coxon sign rank test was conducted on the sections of the SELT-M before and after the life review interviews. 2.3. Results As shown in Tab le 2, overall QOL and Spirituality sus- cale scores, in addition to Mood and Orientation suscale scores, significantly increased after the intervention. 3. STUDY 2 SHORT-TERM LIFE REVIEW Although structured life review may be effective in improving the spiritual well-being of terminally ill cancer patients, the long sessions decrease the feasi- bility, thus we need a shorter version of life review therapy. We propose a new psychotherapy-the Short- Term Life Review with short sessions for terminally ill cancer patients. A Short-Term Life Review involves only two sessions. Patients review or narrate their lives about questions which promote the integration of lives referring other previous studies. In the first ses- sion, patients review their lives, and the review is then recorded and edited. The therapist makes an album after the first session. In the second session, the pa- tient and therapist view the album, and confirm the contents with appreciation. 3.1. Purpose The primary aim of this study was to assess the efficacy of the Short-Term Life Review on the spiritual well- being, as well as anxiety, depression, sufferings, and happiness, or terminally ill cancer patients.  M. Ando et al. / Health 2 (2 010) 342-346 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 344 Table 2. Mean scores and P value by the Wilcoxon sign rank test on scores of SELT-M. SELT-M Physical well-being Mood Support Orientation Spirituality Overall QOL Before 2.33 (SD = 0.79)3. 16 ( S D = 0 . 65 ) 3.28 (SD = 0. 65)2.93 (SD = 0.75)2.57 (SD = 0.61) 2.57 ( SD = 0.61) After 2.80 (SD = 1.16)3.79 (SD = 0. 74) 3.61 (SD = 0. 83)3.65 (SD = 1.03)3.14 (SD = 2.25) 3.58 (SD = 1.0) P value Z = –1.02, P = 0.307 Z = –2.67, P = 0.008 Z = –1.18, P = 0.237 Z = –2.05, P = 0.041 Z = –2.23, P = 0.023 Z = –2.49, P = 0.013 Table 3. Patient backgrounds. Primary tumor site Gender Lung Stomach Pancreas Gallbladder Uterine Breast Kidney Leukemia Rectal Tongue Colon Mesothelioma Myeloma Lymphoma n = 8 n = 5 n = 2 n = 2 n = 2 n = 1 n = 1 n = 1 n = 1 n = 1 n = 1 n = 1 n = 1 n = 1 Male (n = 8) Female (n = 22) Age Mean age;74 (Total SD = 9.1) Martial states Married (n = 29); Widow (n = 11), Widower (n = 3) Non-married (1) Religion Christian (n = 4) Buddhism (n = 3) None(n = 22) ECOG-PS 1 (n = 1), 2 (n = 3) 3 (n = 13), (n = 1 3) Duration from the interview to patients’ death Mean; 67 days 3.2. Methods 3.2.1. Participants The participants were cancer p atients from the palliative care unit of two general hospitals and one home-care clinic. The inclusion criteria for this study were 1) pa- tients with incurable cancer; 2) patients without cogni- tive impairment; 3) patients 20 years of age or older; and 4) patients for whom the primary physicians agreed would benefit from the psychological interventions. During the 11-month study period, 35 patients were re- cruited through primary physicians. Table 3 shows the patients’ background. 3.2.2. Intervention Ethical aspect of this study was validated by both the board and the ethical committee of St. Mary’s Hospital and St. Mary’s College. The Short-Term Life Review has two parts. In the first part, patients review their lives, and in the second, they re-evaluate, re-construct, and appreciate their life. The interviewer was a clinical psychologist (therapist). The interview procedure was based on a structured life re- view interview that was conducted individually, and the patient was asked to re-evaluate both good and bad memories. Question items were mainly based on the structured life review, and some items from Chochinov et al. [13] were added. The following questions were asked in the revi ewi n g sessi o n ( Table 4): 1) What is the most im portant thing in your life and why? 2) W hat are the most impressive memories in your life ? 3) In your life, what was the event that or the person who affected you the most? 4) What is the most important role in your life? 5) Which is the proudest moment of your life? 6) Is ther e anyth ing abou t you th at your family would need to know, are there things you would want them to tell you, and, if possible, are there things you would want them to remember? 7) What advice or word of guidance would you wish to pass on othe important people in your life or to the younger generation? The patient’s narratives were recorded, and the thera pist tried to listen to each word uttered by the patient. Af- ter the first session, the interview was first transcribed verbatim and the therapist made the album. To make the album, 1) key words in the answer to each question were selected. Words or phrases used by the patient were writ- ten in the album as often as possible; both good and bad things were included and feelings or re-framed thoughts- how he feels now-were written in the album. 2) The therapist pasted photos or drawings from various books or magazines that were related to the patients’ words or phrases, to make the album more beautiful and more memory-provoking. It t ook a week for the treatm ent. 3.2.3. Outcome Measurements To measure the effects of the Short-Term Life Review, we used the Japanese version of FACIT-Sp [14]. The validity and reliability of th e FACIT-Sp Japanese version is well-established [15]. 3.2.4. S ta tistical Analysis To evaluate the efficacy of the Short-Term Life Review in improving the patients’ spiritual well-being, the Wil-  M. Ando et al. / Health 2 (2 010) 342-346 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 345 Table 4. The question items in the short-term life review. Question Items 1) Wha t is the most impor t a nt thing in your life and w hy? 2) What are the most impressive memories in your life ? 3) In your life, what was the event that or the person who affected you the most? 4) What is the most important role in your life? 5) Which is the proudest moment of your life? 6) Is there anything about you that your family would need to know, are there things you would want t hem to tell you, and, if possible, are there things you would want them to remember? 7) What advice or word of guidance would you wish to pass on to the important people in your lif e or to the younger generation? coxon signed rank test was conducted on all scores of each scale before and after the Short-Term Life Review. 3.3. Results Five of the patients were excluded from this study be- cause of unexpected deterioratio n in health. Thus, a total of 30 patients completed all sessions. After the Short- Term Life Review, the mean FACIT-Sp scores signifi- cantly increas ed from 16 ± 8.2 to 24 ± 7.1 (Z = –4.2, P = 0.001). 4. DISCUSSION 4.1. Effects of the Structured Life Review and the Short Term-Life Review After the structured life review, the significant increase in the SELT-M scores, as well as the Spirituality, Orien- tation, and Mood subscales shows the efficacy of this therapy on spiritual well-being of terminally ill cancer patients. As the Spirituality and Orientation subscale quantify the levels of the patients’ meaningfulness and positive outlook , the patients may have found a meaning to life and had more positive thoughts. The significant increase in the Mood subscale for terminally ill cancer patients is accord with previous studies for elders [3-5]. After the Short-Term Life Review, the FACIT-Sp scores significantly increased. It shows the effect of this therapy on spiritual well-being of cancer patients. We confirm the efficacy of this therapy even when we com- pare it with the control group [16]. Adapting these proc- ess with the previous theoretical model [17,18], we can explain the effects of Short-Term Life Review. A patient has a purpose or a goal for his life when he is healthy. However, when he falls into serious illness, it is often difficult for him to attain his purpose or a goal because of unexpected serious illness, and he feels much distress. In this situation, when he receives the Short-Term Life Review and he can re-think and modifies his original purpose or goals into attainable ones, he feels positive mood. Short-Term Life Review may contribute for a patient to reconstruct his life being congruent with can- cer in his life. 4.2. Feasibility It would be remarkable for Short-Term Life Review to have high feasibility. Th e percentage of patients deterio- rating with this therapy was only 17%, although, it was 30% for patients using the structured life review. We describe some factors related to feasibility. 1) The Short-Term Life Review is completed in a week, and this short-term intervention enables terminally ill cancer pa- tients to complete an intervention. 2) Patients with very low functionality in ADL can participate because the patients review th eir lives wh ile lying on b ed. If p atien ts’ ADL is high, the Problem-solving therapy for cancer patients [19] and cognitive behavior therapy for cancer patients [20], or meaning-centered group psychotherapy [21] are also effective. 4.3. Characteristics of Each Life Review There are some characteristics of each therapy. The structured life review is suitable for patients who have much time for interviews and require little cognitive load. Oppositely, The Short-Term Life review is suitable for patients who do not have much time for interviews and require a little more cognitive load. In the Short-Term Life review, a patient needs to think of his life pro- foundly, resulting in requiring much cognitive load. We use these therapies understanding patients’ physical and mental states. 5. CONCLUSIONS Both the structured life review and the Short-Term Life Review have efficacy on spiritual well-being of termi- nally ill cancer patients, being higher feasibility for the Shot-Term Life Review. We need to use these therapies understanding characteristics of each therapy. REFERENCES [1] Murata, H. and Morita, T. (2006) Conceptualization of psycho-existential suffering by the Japanese Task Force: The first step of a nationwide project. Pattern of Pallia- tive Care, 4, 279-285.  M. Ando et al. / Health 2 (2 010) 342-346 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 346 [2] Butler, R.N. (1974) Successful aging and the role of the life review. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 22, 529-535. [3] Haight, B., Coleman, P.G., and Lord, K. (1995) The linchpins of a successful life review: Structure, evalua- tion, and individuality. In Haight, B.K. and Webster, J.D. (Eds) The art and science of reminiscing: theory, research, methods and applications. Bristol, P.A: Taylor & Francis, 179-192. [4] Haight, B., Michel, Y., and Hendrix, S. (1998) Life re- view: Preventing despair in newly relocated nursing home residents: Short- and long-term effects. Interna- tional Journal of Aging and Human Development, 47, 119-142. [5] Haight, B., Michel, Y., and Hendrix, S. (2000) The ex- tended effects of the life review in nursing home resi- dents. International Journal of Aging and Human De- velopment, 50, 151-168. [6] Jones, E.D. and Beck-Little, R. (2002) The use of remi- niscence therapy for the treatment of depression in ru- ral-dwelling older adults. Issues in Mental Health Nurs- ing, 23, 279-290. [7] Haight, B.K. (1988) The therapeutic role of a structured life review process in homebound elderly subjects. Journal of Gerontology, 43, 40-44. [8] Ando, M., Tsuda, A., and Morita, T. (2007) A preliminary study of life review interviews on the spiritual well-being of terminally ill ca n cer patients . Support Care Cancer, 15, 225-231. [9] Ando, M., Morita, T., Okamoto, T., and Ninosaka, Y. (2009) One week Short-Term Life Review interview can improve spiritual well-being of terminally ill cancer pa- tients. Psycho-Oncology, 17, 885-890. [10] Erikson, E.H. (1959) Identity and the life cycle. Interna- tional University Press, New York. [11] Wegberg, B.V., Bacchi, M., and Heusser, P., et al. (1998) The cognitive-spiritual dimension:-an important addition to the assessment of quality of life: Validation of a ques- tionnaire (SELT-M) in patients with advanced cancer. Annals of Oncology, 9, 1091-1096 [12] Ishikawa, K. (2000) Spiritual QOL. Palliat Med, 2, 173-181 (in Japanese). [13] Chochinov, H.M., Hack, T., Hassard, T., et al. (2005) Dignity therapy: A novel psychotherapeutic intervention for patients near the end of life. Journal of Clinical On- cology, 23, 5520-5525. [14] Peterman, A.H., Fitchett, G., Brady, M.J., et al. (2002). Measuring spiritual well-being in people with cancer: The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Ther- apy-Spiritual Well-Being Scale (FACIT-Sp), Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 24, 49-58. [15] Noguchi, W., Ono, T., Morita, T., et al. (2004) An inves- tigation of reliability and validity to Japanese version of Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Ther- apy-Spiritual (FACIT-sp), Japan Journal of General Hospital Psychiatry, 16, 42-47 [16] Ando M, Morita T, Akechi T, et al. (2009) The efficacy of Short-Term Life Review interviews on the spiritual well-being of terminally ill cancer patients. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, in press [17] Park, C.L. and Folkman, S. (1997) Meaning in the con- text of stress and coping. Review Genel Psycholo, 1, 115-144. [18] Folkman, S. and Greer, S. (2000) Promoting psychologi- cal well-being in the face of serious illness: when theory, research and practice inform each other. Psy- cho-Oncology, 9, 11-19. [19] Nezu, A.M., Nezu, C.M., Friedman, S.H., et al. (2002). Psychosocial oncology. In Nezu A.M., Nezu C.M., Geller P.A. Eds., Health psychology, Handbook of Psychology, Wiley, 9, 121-156. [20] Greer, S. and Moorey, S. (1997) Adjuvant psychological therapy for cancer patients. Palliat Med, 11, 240-244. [21] Breitbert, W. (2002) Spirituality and meaning in suppor- tive care: spirituality- and meaning-centered group psy- chotherapy interventions in advanced cancer. Support Care Cancer, 10, 272-280.. |