Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

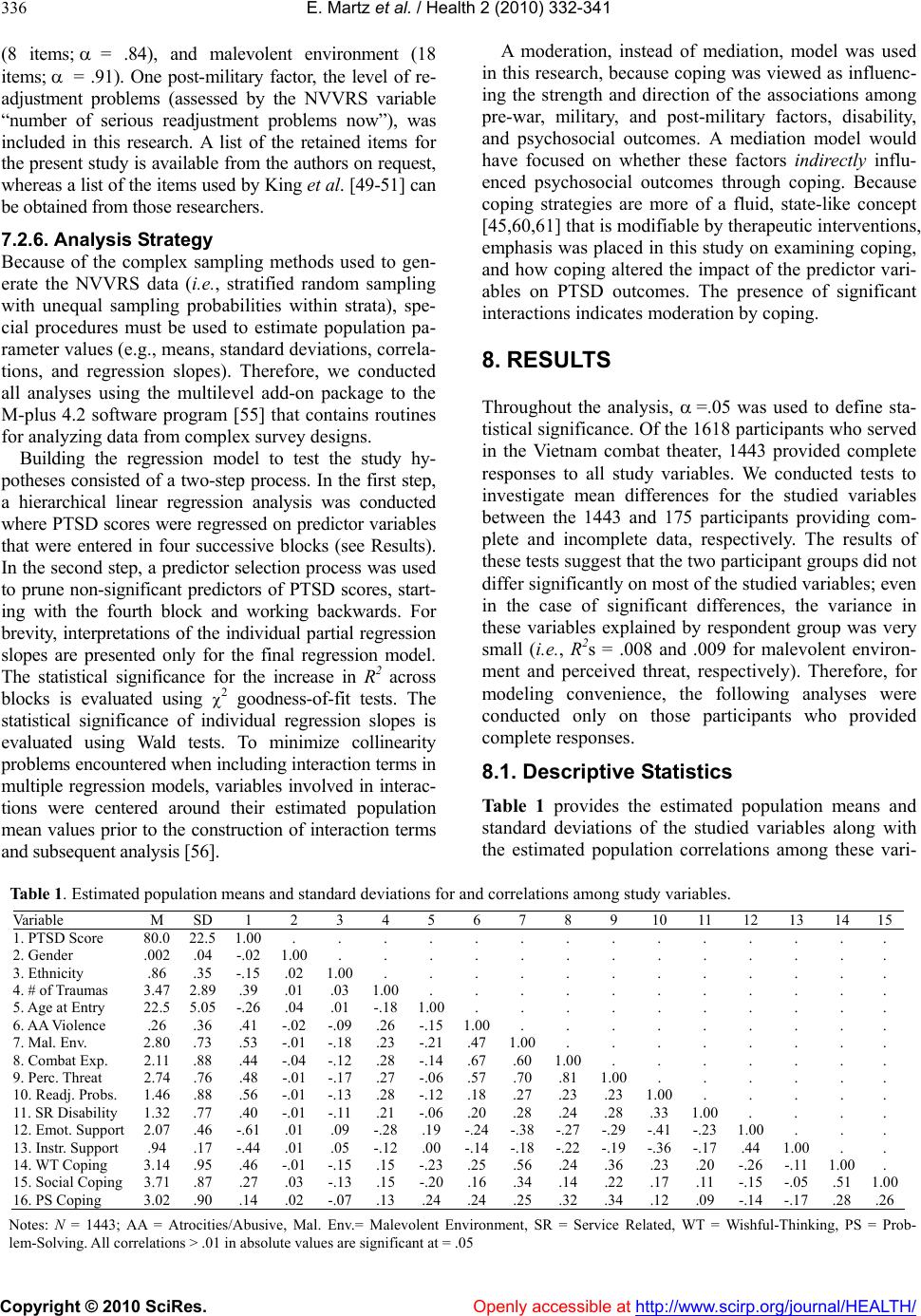

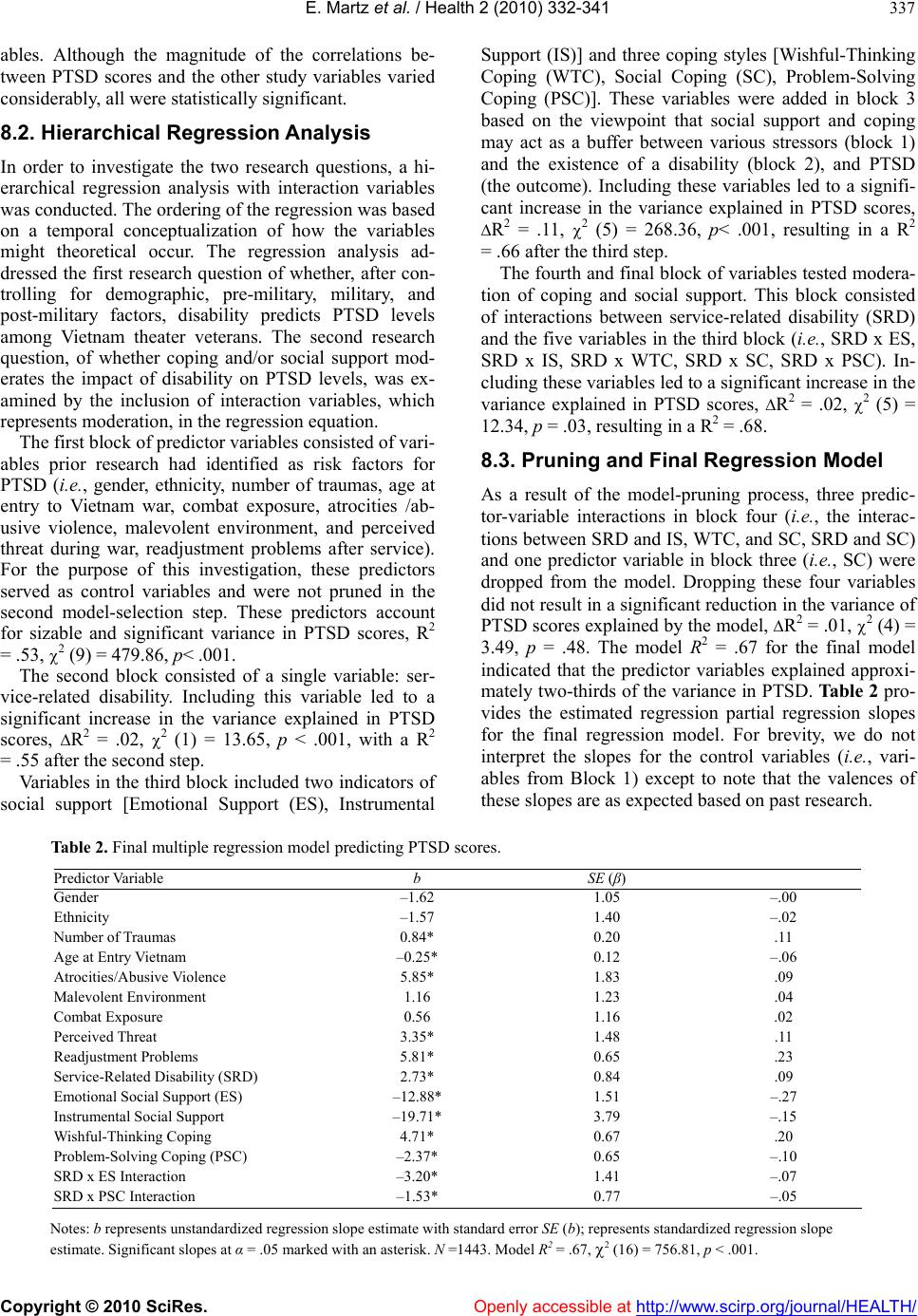

Vol.2, No.4, 332-341 (2010) Health doi:10.4236/health.2010.24050 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ Social support and coping as moderators of perceived disability and posttraumatic stress levels among Vietnam theater veterans Erin Martz*, Todd Bodner, Hanoch Livneh Portland State University, Portland, USA; martzerin@gmail.com Received 3 December 2009; revised 11 January 2010; accepted 15 January 2010. ABSTRACT The dual purpose of this study is to investigate whether disability predicts posttraumatic stress levels among Vietnam theater veterans, and whether coping and/or social support moder- ates the impact of disability on PTSD levels, after controlling for demographic, pre-military, military, and post-military factors. This research analyzed data from the U.S.’s National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study (NVVRS), which was a nationally representative, stratified, ran- dom sample of 3,016 Vietnam veterans. The re- sults indicated that disability, emotional support, instrumental support , and wishful – thinking cop - ing significantly predicted PTSD, when control- ling for demographic, pre-military, military, and post-military factors. Further, interactions indi- cated that both emotional social support and problem-solving coping significantly decreased the impact of disability on PTSD levels. Implica- tions of this research are briefly discussed. Keywords: Disability; Social Support; PTSD; Vietnam Veterans 1. INTRODUCTION An extensive amount of published research has exam- ined psychiatric disorders, which may include posttrau- matic stress disorder (PTSD), as sequelae of involve- ment in wars [1-4]. While some research has focused on the physical health consequences of exposure to extreme stress [5,6], limited research has been conducted on the psychological reactions occurring after the onset of an injury or permanent disability in the context of war [7,8]. Moreover, there is a paucity of research on PTSD related to disability that occurred specifically in a war-zone. There has been increasing scientific interest on coping with a disability [9]; yet, few studies have been conduc t e d that examined coping with a war-related disability. To date, research has not yet examined the possible moder- ating effect of coping or social support on disability and PTSD levels. The need to conduct such research has been stated by Kulka and colleagues, who concluded that “Vietnam theater veterans with service-connected physical dis- abilities are at elevated risk for a variety of readjustment problems” [1], and more recently, by a 2006 working group on deployment-related adjustment and mental disorders [10]. The dual purpose of this study is to in- vestigate whether disability predicts PTSD levels among Vietnam theater veterans, and whether there are possible moderators of this association, such as coping or social support, after controlling for select demographic, pre- military, military, and post-military related variables. The following sections will review the extant literature on: 1) PTSD and disability; 2) coping and PTSD; and 3) the significant findings of research that examined PTSD in analyses of the NVVRS dataset. 2. PTSD AND DISABILITY When evidence of a traumatic event remains present in an individual’s life, such as in the form of an injury or disability, it may serve as a visual or proprioceptive cue to the trauma [11,12]. Thus, injury or disability may act as a continuous reminder that can trigger anxiety for certain individuals. Research has indicated an associa- tion between PTSD and the existence of injuries, medi- cal conditions, or disabilities [13-18], and that individu- als may be susceptible to PTSD after an injury or the onset of a disability [11,14,16,17,19-23]. In research conducted among veterans, Helzer, Robins, and McEvoy [24] examined PTSD rates in a stratified sample among 2,493 individuals, 64 of whom were Vietnam veterans and 43 had experienced combat. Those who experienced combat but were not wounded had a 4% rate of PTSD, compared to 20% rate among those who were wounded. In a comparative study, Buydens-  E. Martz et al. / Health 2 (2010) 332-341 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 333 Branchey, Noumair, and Branchey [25] found that vet- erans with a combat injury had significantly higher PTSD levels compared to veterans without injuries. Martz and Cook [26] found the following rates of PTSD among 45,320 veterans: burns 13.4%, spinal cord injuries 11.6%, amputations 8.1%, major chest trauma 7.6%, heart failure/shock 7.3%, and cardiac arrest 5.1%. They found that burns, spinal cord injuries, amputations, and heart failure/shock were significant risk factors for PTSD. Delimar and Sivik [27] assessed for PTSD in three groups of so ldiers (N = 30 per group ), all of whom had at least three months of combat experience in the Croatian war of 1991-1993, and found a PTSD rate of 33.3% among soldiers with permanent disabilities (e.g., amputation). Among 312 veterans and civilians with spinal cord injuries, Martz [28] found that total PTSD levels were significantly predicted by spiritual/religious coping, pain level, severity of SCI, and number of trau- matic events. The topic of PTSD reactions after the presence of a disability among veterans is important for several rea- sons. Kaplan, Huguet, McFarland, and Newsom [29] found that male veterans who had activity limitations (i.e., a disability) were significantly more likely to com- mit suicide than non-veterans without disabilities. Fur- ther, the topic of war-related physical disability as a po- tential trigger for PTSD reactions is imperative to study, in view of the concept of “double PTSD” [13], which in the present context can mean that the trauma of disabil- ity interacts with the trauma of war. Disability may also be a “crossover” trauma, which Terr [30] described as a one-time event with long-term, continuous consequences that may elicit a complex set of traumatic reactions. Kulka et al. [1] analyzed data from the U.S.’s Na- tional Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study (NVVRS), which was an epidemiological study of a nationally representative sample of Vietnam veterans. One part of their extensive analysis examined issues related to Vietnam veterans’ physical health problems in relation to PTSD versus no PTSD (see Exhibit VIII-2, contrast C, in [1 ]). The result s indicated th at for both ma les and femal es, in d ivid u als with P TSD rep or ted a s ign if ic ant ly lower level of positive perceptions of current health status and a significantly higher number of chronic health problems than those without PTSD. In a differ- ent section, Kulka et al. [1] reported that the group of Vietnam veterans with a service-connected physical disability (SCPD) was significantly more likely to have current PTSD (21.4%) than the group of veterans without a SCPD (14.5%) (current PTSD prevalence indicates that the individual met the PTSD criteria within 6 months of the assessment; lifetime PTSD prevalence indicates that the individual met the criteria for PTSD sometime in their life; see Reference [1]). To put the disability and PTSD research in context, the results of the NVRRS research on war-related PTSD include the following. Kulka et al. [1] indicated that 15.2% of male combat veterans and 8.5% of female combat veterans from the Vietnam war-theater met the criteria for current PTSD prevalence. In contrast to the NVVRS prevalence data, the current PTSD prevalence found among Gulf War veterans were found to be 4% of men and 9% of women at first assessment, increas- ing to 11% of men and 21% of women at second as- sessment 2 years later [31]. The aforementioned current PTSD prevalence rates and the two findings related to health factors, disability, and PTSD suggest that the traumatic experience of incurring a disability is an is- sue that deserves more careful investigation and greater clarification of the associations, such as examining the possible predictors of PTSD levels among veterans and the possible mod erato rs of thes e associ ations . The present research is distinct from three studies that were published using the NVVRS database. First, in contrast to Zatzick and colleagues’ [6] research that ex- amined PTSD and health outcomes and functioning, the present study incorporates a measure indicating an exis- tence of a disability, in addition to also examining mod- erators of PTSD. Second, whereas Suvak, Vogt, Savarese , King, and King [32] researched coping as a predictor of adjustment (moderated by war-zone stress) without ex- amining disability issues, the presen t study posits coping as a moderator between disability and PTSD. Third, while Martz, Bodner, and Livneh [33] examined coping as a moderator of disability and adaptation, the current study will investigate a different outcome—that of PTSD—and whether both coping and social support are moderators of disability and PTSD. 3. COPING AND PTSD Regarding PTSD and coping research, a variety of asso- ciations have been found among various types of coping and PTSD [34-37]. Koenen, Stellman, and Stellman [38], in a follow-up study of 1,377 American legionnaires who served in Southeast Asia, concluded from their findings that perceived social support is a significant predictor of recovery from PTSD. One study examined coping and PTSD in the context of disability: Lawrence and Fauerbach [39] found that both avoidant and active coping were positively and significantly associated with PTSD at hospitalization and at 1-month follow-up among 158 individuals with burn injuries. Using the NVVRS dataset, Suvak et al. [32] exam- ined whether war-zone coping strategies predicted life adjustment, as measured by achievement, life satisfac- tion, and lifetime adaptation, and as moderated by combat exposure. Their study is mentioned because of its use of coping strategies, which were grouped into 3 factors called problem-focused coping (PFC), emo-  E. Martz et al. / Health 2 (2010) 332-341 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 334 tion-focused wishful thinking (EFCWT), and emo- tion-focused blunting and venting (EFCBV). One find- ing that is relevant to the present study is that Suvak and colleagues noted that in the final step of their re- gression analysis, non-linear (i.e., quadratic) associa- tions were found among PFC and achievement, PFC and lifetime adaptation, and EFCWT and achievement, each varying as a function of combat exposure. This research indicated that the use of emotional coping strategies during combat predicted lowered life-ad- justment after the war experience, which Suvak and colleagues interpreted the non-linear associations as suggesting that certain coping strategies are no longer useful in increasingly stressful combat situations. The research on coping with a disability has been expanding at a rapid rate [40-44], (for a summary, see [9]). The role of coping strategies following traumatic brain injury (TBI) was investigated by Moore and Stambrook [43,44]. In their earlier study of 53 male survivors of TBI, individuals characterized by having 1) higher use of positive reappraisal and self-controlling coping strategies (as measured by the Ways of Cop- ing-Revised Questionnaire; WOC-R), and 2) lower external locus of control, reported significantly lower mood disturbance and lower levels of depression. In the authors’ latter study of 175 survivors of TBI, they re- ported that coping strategies that included denial, es- cape, and resignation were linked to poorer qual- ity-of-life outcomes. The authors also suggested that positive reappraisal appeared to be associated with better psychosocial outcomes. 4. COPING A SOCIAL SUPPORT Social support, which can be defined as “the perception of the value of social interactions” [45], should be dis- tinguished from the concept of a “social network,” which refer to the quantity of relationships that a per- son has. Lazarus and Folkman [45] further elaborated on the definition of social support as “a resource, available in the social environment, but which the per- son must cultivate and use” [45]. They also noted that while social support is typically deemed as a positive resource and a buffer to stress, it also may have nega- tive effects on people (e.g., it may create problems or stress, provide misleading information, or create de- pendency issues). Thoits [46] suggested that social support could be viewed as a form of coping assistance or support strategy. Livneh and Martz [9] noted that social support can be viewed as an “extra-individual” influence on coping pro- cesses, like other environmental factors. Hence, social support can be distinguished from a form of emotional coping called “seeking social support” by the former representing social support that is received and experi- enced, versus the latter as actions taken to obtain social support. 5. PREDICTORS OF PTSD USING THE NVVRS DATA The following NVVRS research indicated variables that should be controlled for in the present study. Fontana and Rosenheck’s [47] research examined predictors of PTSD by using structural equation modeling (SEM) among a male sub-sample from the NVVRS data. One demographic predictor (ethnicity), 2 military-related variables (exposure to combat and participation in abu- sive violence), and 2 post-military traumas (rejection by society at homecoming, and lack of support by family and friends) directly predicted PTSD. In a later study using NVVRS data, Fontana and Rosenheck [48] fo- cused only on war-zone stressors among male veterans. Their SEM analysis indicated that only 2 variables had direct, significant effects on PTSD: insufficiency of re- sources in the environment and killing of others. King and colleagues published 3 different analyses using the NVVRS dataset. Using SEM, King, King, Gudanowski, and Vreven’s [49] research, which focused only on war-zone stressors, indicated that the following war-zone stressors significantly predicted PTSD: per- ceived threat, malevolent environment, and atrocities/ abusive violence. King, King, Foy, and Gudanowski [50] examination of pre-war factors and war-zone stressors found that for male and female theater veterans, prior trauma history, age (for men only), atrocities/abusive violence, malevolent environment, and perceived threat had significant direct effects on PTSD. King, King, Foy, Keane, and Fairbank’s [51] NVVRS research indicated that the following predicted PTSD: early trauma history (women and men) and age at entry into Vietnam (men), atrocities-abusive violence and perceived threat (for both men and women) and malevolent environment (for men), additional stressful life events, hardiness, and functional social support (for men and women) and structural social support (for men). 6. RESEARCH QUESTION AND HYPOTHESES The purpose of this research is two-fold: to investigate, after controlling for demographic, pre-military, military, and post-military factors, whether 1) disability predicts PTSD levels in Vietnam theater veterans, and 2) coping and/or social support moderates the impact of disability on PTSD levels. Based on the literature about coping, it is hypothesized that emotion-focused coping is posi- tively related to PTSD levels, while social support, so- cial coping, and problem-solving coping are inversely related to PTSD levels.  E. Martz et al. / Health 2 (2010) 332-341 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 335 7. METHOD 7.1. Participants The data were obtained from the National Vietnam Vet- erans Readjustment Study (NVVRS), a nationally repre- sentative, stratified, random sample of 3,016 Vietnam veterans drawn from 8.2 million veterans who were on active duty during the Vietnam war and who had left U.S. military service by September, 1987 [52]. The data were collected by means of extended interviews and self-re- port questionnaires between 1986 and 1988 [1,2]. Sev- eral groups were intentionally over-sampled in this study: African Americans, Hispanics, women, and veterans with service-connected disabilities [49]. Refer to Kulka et al. [1,2] for an extensive summary of demographic characteristics of this sample. In the current study, we limited our attentio n to the 1618 theater veterans, that is, only those who served within the war theater. For this study, all the NVVRS data were used in factor analyses of the variables. For the examination of the research questions, the data from the Vietnam theater veterans (n = 1618) were used, due the large amounts of missing data for the variables considered among other participants (e.g., non-theater veterans, civilians) in the NVRRS dataset. 7.2. Instruments 7.2.1. PTSD In the NVVRS, a multi-method approach was used to assess PTSD with 3 primary and 7 secondary indicators of PTSD [1]. For this research, the Mississippi Scale for Combat Related Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (M-PTSD) was selected because it has been used extensively for measuring PTSD.The M-PTSD is a 35-item scale by Keane, Caddell, and Taylor [53] that measures posttrau- matic stress in military situations with higher scores in- dicating greater likelihood of PTSD. Weiss et al. [52] reported on the predictive validity of the various PTSD scales used in the NVVRS; when comparing the survey data with clinicians’ assessments, the M-PTSD achieved a 77.3 sensitivity rate, 82.8 specificity rate, and a Kappa of .53 for diagnosing PTSD. 7.2.2. Coping In the NVVRS, 25 coping items were included, derived from a large number of coping items from Folkman and Lazarus’s [54] Ways of Coping Checklist [see 32 for more details]. The original team of NVVRS researchers selected these items as “most appropriate to coping with the stressors of a war zone” [32]. The responses, after reverse-coding, r epresented how much the veteran relied on each way of coping (i.e., 1 = not at all to 5 = a great deal). Prior research [33] on these items in the NVVRS dataset has identified three distinguishable coping- strategy dimensions: wishful-thinking coping (4 items; = .78), social coping (2 items; = .67), and prob- lem-solving cop ing (4 items; = .78). The social coping factor included items about whether the respondent “de- pended on o thers to cheer you up” and “saw someone to help feel better.” Hence, social coping reflects strategies that individuals use to handle stress, which in contrast to the social support variable, refer to perceived external support that is provided to individuals. 7.2.3. Instrumental and Emotional Social Support To measure instrumental and emotional social support, we used the 6-item Instrumental Social Support (= .75) and 13-item Emotional Social Support ( = .77) scales, respectively, which King et al. [49-51] formulated from the NVVRS items and described in detail in their publi- cations. Higher scale scores indicated greater levels of each type of social support. 7.2.4. Disability To assess disability, we used participan t responses to the following question (item K4b in the NVVRS database): “A military service-received wound handicapped me later.” The response format was on a scale ranging from 1 “very true” to 4 “not at all true,” which was re- verse-scored so that higher scores indicate stronger be- lief that one had a service-related disability. This disabil- ity item was selected from the available NVVRS item pool because: a) it was a continuous, not categorical variable; b) the question made a direct connection be- tween injury incurred in the service and a disabling status at a later time (i.e., a permanent disability, not a temporary injury); and c) it was not a variable that rep- resented financial compensation from the Veterans Ad- ministration. Thus, the current research team deemed it the best NVVRS item that represented d isability. 7.2.5. Demographic, Pre-milit ary, Military, and Post-milit ary Risk Factors Pre-military risk factors included gender (female = 1, male = 0), ethnicity (1 = white, 0 = otherwise) [these two variables, as categorical variables, were binary-coded for the multiple regression], the number of traumatic events experienced, and age at entry into Vietnam. Prior research [49-51] measured the following four facets of mili- tary-related stress in a war-zone: combat exposure (36 items), atrocities and abusive violence exposure (9 items), perceived threat (9 items), and malevolent environment (18 items). In our own analyses, we determined that many of these scales were multidimensional and that many items had large amounts of missing values. We therefore created scales for these facets based on subsets of the original itempool to improve the unidimensionality of the scales and to minimize the amount of missing data. The resulting scales had the following properties, with higher scores indicating higher levels of each military-related risk factor: combat exposure (12 items; = 92), atrocities and abusive violence (3 items; = .76), perceived threat  E. Martz et al. / Health 2 (2010) 332-341 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 336 (8 items;= .84), and malevolent environment (18 items; = .91). One post-military factor, the level of re- adjustment problems (assessed by the NVVRS variable “number of serious readjustment problems now”), was included in this research. A list of the retained items for the present study is avai lable from the authors on request, whereas a list of the items used by King et al. [49-51] can be obtained from those researchers. 7.2.6. Analysis Strategy Because of the complex sampling methods used to gen- erate the NVVRS data (i.e., stratified random sampling with unequal sampling probabilities within strata), spe- cial procedures must be used to estimate population pa- rameter values (e.g., means, standard deviations, correla- tions, and regression slopes). Therefore, we conducted all analyses using the multilevel add-on package to the M-plus 4.2 software program [55] that contains routines for analyzing data from complex survey designs. Building the regression model to test the study hy- potheses consisted of a two-step process. In the first step, a hierarchical linear regression analysis was conducted where PTSD scores were regressed on predictor variables that were entered in four successive blocks (see Results). In the second step, a predictor selection process was used to prune non-significant predictors of PTSD scores, start- ing with the fourth block and working backwards. For brevity, interpretations of the individual partial regression slopes are presented only for the final regression model. The statistical significance for the increase in R2 across blocks is evaluated using 2 goodness-of-fit tests. The statistical significance of individual regression slopes is evaluated using Wald tests. To minimize collinearity problems encountered when including interaction terms in multiple regression models, variables involved in interac- tions were centered around their estimated population mean values prior to the construction of interaction terms and subsequent analysis [56]. A moderation, instead of mediation, model was used in this research, because coping was viewed as influenc- ing the strength and direction of the associations among pre-war, military, and post-military factors, disability, and psychosocial outcomes. A mediation model would have focused on whether these factors indirectly influ- enced psychosocial outcomes through coping. Because coping strategies are more of a fluid, state-like concept [45,60,61] that is modifiable by th erapeutic interv entions , emphasis was placed in this study on examining coping, and how coping altered the impact of the predictor vari- ables on PTSD outcomes. The presence of significant interactions indicates moderation by coping. 8. RESULTS Throughout the analysis, =.05 was used to define sta- tistical significance. Of the 1618 participants who served in the Vietnam combat theater, 1443 provided complete responses to all study variables. We conducted tests to investigate mean differences for the studied variables between the 1443 and 175 participants providing com- plete and incomplete data, respectively. The results of these tests suggest that the two participant group s did not differ signif ican tly on mo s t of th e s tu d ied var ia b les ; ev en in the case of significant differences, the variance in these variables explained by respondent group was very small (i.e., R2s = .008 and .009 for malevolent environ- ment and perceived threat, respectively). Therefore, for modeling convenience, the following analyses were conducted only on those participants who provided complete responses. 8.1. Descriptive Statistics Table 1 provides the estimated population means and standard deviations of the studied variables along with the estimated population correlations among these vari- Table 1. Estimated population means and standard deviations for and correlations among study variables. Variable M SD 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 1. PTSD Score 80.0 22.5 1.00 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2. Gender .002 .04 -.02 1.00 . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3. Ethnicity .86 .35 -.15 .02 1.00 . . . . . . . . . . . . 4. # of Traumas 3.47 2.89 .39 .01 .03 1.00. . . . . . . . . . . 5. Age at Entry 22.5 5.05 -.26 .04 .01 -.181.00. . . . . . . . . . 6. AA Violence .26 .36 .41 -.02 -.09 .26-.151.00. . . . . . . . . 7. Mal. Env. 2.80 .73 .53 -.01 -.18 .23-.21.471.00. . . . . . . . 8. Combat Exp. 2.11 .88 .44 -.04 -.12 .28-.14.67.601.00. . . . . . . 9. Perc. Threat 2.74 .76 .48 -.01 -.17 .27-.06.57.70.811.00. . . . . . 10. Readj. Probs. 1.46 .88 .56 -.01 -.13 .28-.12.18.27.23.231.00. . . . . 11. SR Disability 1.32 .77 .40 -.01 -.11 .21-.06.20.28.24.28.331.00 . . . . 12. Emot. Support 2.07 .46 -.61 .01 .09 -.28.19-.24-.38-.27-.29-.41-.23 1.00 . . . 13. Instr. Support .94 .17 -.44 .01 .05 -.12.00-.14-.18-.22-.19-.36-.17 .44 1.00 . . 14. WT Coping 3.14 .95 .46 -.01 -.15 .15-.23.25.56.24.36.23.20 -.26 -.11 1.00. 15. Social Coping 3. 71 .87 .27 .03 -.13 .15-.20.16.34.14.22.17.11 -.15 -.05 .511.00 16. PS Coping 3.02 .90 .14 .02 -.07 .13.24.24.25.32.34.12.09 -.14 -.17 .28.26 Notes: N = 1443; AA = Atrocities/Abusive, Mal. Env.= Malevolent Environment, SR = Service Related, WT = Wishful-Thinking, PS = Prob- lem-Solving. All correlations > .01 in absolute values are significant at = .05  E. Martz et al. / Health 2 (2010) 332-341 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 337 ables. Although the magnitude of the correlations be- tween PTSD scores and the other study variables varied considerably, all were statistically significant. 8.2. Hierarchical Regression Analysis In order to investigate the two research questions, a hi- erarchical regression analysis with interaction variables was conducted. The ordering of the regression was based on a temporal conceptualization of how the variables might theoretical occur. The regression analysis ad- dressed the first research question of whether, after con- trolling for demographic, pre-military, military, and post-military factors, disability predicts PTSD levels among Vietnam theater veterans. The second research question, of whether coping and/or social support mod- erates the impact of disability on PTSD levels, was ex- amined by the inclusion of interaction variables, which represents moderation, in the regression eq uation. The first bl oc k of predictor varia bles consist ed of vari- ables prior research had identified as risk factors for PTSD (i.e., gender, ethnicity, number of traumas, age at entry to Vietnam war, combat exposure, atrocities /ab- usive violence, malevolent environment, and perceived threat during war, readjustment problems after service). For the purpose of this investigation, these predictors served as control variables and were not pruned in the second model-selection step. These predictors account for sizable and significant variance in PTSD scores, R2 = .53, 2 (9) = 479.86, p< .001. The second block consisted of a single variable: ser- vice-related disability. Including this variable led to a significant increase in the variance explained in PTSD scores, R2 = .02, 2 (1) = 13.65, p < .001, with a R2 = .55 after the second step. Variables in the third block included two indicators of social support [Emotional Support (ES), Instrumental Support (IS)] and three coping styles [Wishful-Thinking Coping (WTC), Social Coping (SC), Problem-Solving Coping (PSC)]. These variables were added in block 3 based on the viewpoint that social support and coping may act as a buffer between various stressors (block 1) and the existence of a disability (block 2), and PTSD (the outcome). Including these variables led to a signifi- cant increase in the variance explained in PTSD scores, R2 = .11, 2 (5) = 268.36, p< .001, resulting in a R2 = .66 after the third step. The fourth and final block of variables tested modera- tion of coping and social support. This block consisted of interactions between service-related disability (SRD) and the five variables in the third block (i.e., SRD x ES, SRD x IS, SRD x WTC, SRD x SC, SRD x PSC). In- cluding these variables led to a significant increase in the variance explained in PTSD scores, R2 = .02, 2 (5) = 12.34, p = .03, resulting in a R2 = .68. 8.3. Pruning and Final Regression Model As a result of the model-pruning process, three predic- tor-variable interactions in block four (i.e., the interac- tions between SRD and IS, WTC, and SC, SRD and SC) and one predictor variable in block three (i.e., SC) were dropped from the model. Dropping these four variables did not result in a significant reduction in the variance of PTSD scores explained by the model, R2 = .01, 2 (4) = 3.49, p = .48. The model R2 = .67 for the final model indicated that the predictor variables explained approxi- mately two-thirds of the variance in PTSD. Table 2 pr o- vides the estimated regression partial regression slopes for the final regression model. For brevity, we do not interpret the slopes for the control variables (i.e., vari- ables from Block 1) except to note that the valences of these slopes are as expected based on past research. Table 2. Final multiple regression model predicting PTSD scores. Predictor Variable b SE (β) Gender –1.62 1.05 –.00 Ethnicity –1.57 1.40 –.02 Number of Traumas 0.84* 0.20 .11 Age at Entry Vietnam –0.25* 0.12 –.06 Atrocities/Abusive Violence 5.85* 1.83 .09 Malevolent Environment 1.16 1.23 .04 Combat Exposure 0.56 1.16 .02 Perceived Threat 3.35* 1.48 .11 Readjustment Problems 5.81* 0.65 .23 Service-Related Disability (SRD) 2.73* 0.84 .09 Emotional Social Support (ES) –12.88* 1.51 –.27 Instrumental S ocial Support –19.71* 3.79 –.15 Wishful-Thinking Coping 4.71* 0.67 .20 Problem-Solving Coping (PSC) –2.37* 0.65 –.10 SRD x ES Interaction –3.20* 1.41 –.07 SRD x PSC Interaction –1.53* 0.77 –.05 Notes: b re presents unstandardized regression slope esti mate with standard error SE (b); represents standardized regression slope estimate. Significant slopes at α = .05 marked with an asterisk. N =1443. Model R2 = .67, 2 (16) = 756.81, p < .001.  E. Martz et al. / Health 2 (2010) 332-341 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 338 Controlling for the other predictor variables in the model, ES, IS, and PSC (at the mean of SRD) were negatively and significantly related to PTSD scores and WTC was positively and significantly related to PTSD scores. Furthermore, controlling for the other variables in the model, SRD was positively and significantly re- lated to PTSD scores (at the mean of the ES and PSC variables). However, the effect of SRD on PTSD scores was qualified by significant interactions with ES and PSC. In particular, the impact of SRD on PTSD scores was smaller for both those with higher levels of ES and higher levels of PSC. 9. DISCUSSIONS The two-fold purpose of this study was to examine whether perceived disability predicted PTSD levels and whether coping and/or social support moderated the im- pact of perceived disability on PTSD levels, after con- trolling for demographic, pre-military, military, and post-military factors. The results ind icated that p erceived disability occurring during military service significantly predicted PTSD, when controlling for other stressors, such that more pronounced perceived disability is asso- ciated with higher PTSD levels. Further, emotional so- cial support (ES) was found to moderate between per- ceived disability and PTSD, in dicating that the existen ce of a disability had less of an influence on PTSD levels among those with higher levels of ES. Problem-solving coping (PSC) also moderated the association of per- ceived disability and PTSD, such that a service-related disability (SRD) had less influence on PTSD scores for individuals with higher levels of problem-solving coping. That perceived disability was a significant predictor of PTSD scores over and above other variables already identified in the literature corresponds with what previ- ous research has found in the general population [14-18] and among veterans [25,26]. As discussed at the begin- ning of this paper, Kulka and his colleagues [1,2] pre- sented basic results regarding PTSD prevalence and disability; the present research helps to refine this asso- ciation by conducting a multivariate analysis that con- trolled for multiple sources of stressors, and by examin- ing coping interactions. The direction of the significant zero-order correlation between PTSD and emotion-focused, wishful-thinking coping was in the hypothesized direction (r = .46, p = .05), indicating that higher use of wishful-thinking coping (WTC) was related to increased levels of PTSD. Yet, the direction of the zero-order correlation between PTSD and problem-solving coping was opposite (higher use of problem-solving coping was related to increased levels of PTSD) to what was hypothesized (r = .14, p = .05). However, this zero-order relationship was re- versed (r = -.10, p =.05), when examined through re- gression analysis. Two possible explanations for this phenomenon include: a) the operation of a minimal amount of suppression, and/or b) the fact that after con- trolling for all other confounding variables, the use of problem-solving coping does act to attenuate the influ- ence of disability on PTSD symptomatology, as origi- nally hypothesized. This study’s finding that problem-solving coping moderates the association of perceived disability and PTSD concurs with research on the role played by prob- lem-solving coping in decreasing the impact of a range of stressors. For example, Kennedy, Lowe, Grey, and Short [57], in a sample of people with traumatic spinal cord injuries, found a negative correlation between problem-solving coping (active coping and planning) and measures of depression, anxiety, and global psycho- logical distress. Therapeutic interventions that integrate problem-solving components (e.g., decision making, time management, conflict resolution, money manage- ment) could become useful in countering the impact of functional impairments that are associated with d isability. One example of such programs is Kennedy and Duff’s program [62,63] for coping effectively with spinal cord injuries. Problem-solving is a life-skill that can be used for general problems, as well as for challenges directly related to disability-related issues. Because the ex istence of a disability often involves numerous challenges on multiple levels (e.g., psychological, social, vocational, environmental), therapeutic interventions to strengthen problem-solving coping can help individuals better adapt to their lives following the onset of disability. The significant zero-order correlations between PTSD and both emotional social support (r = -.6 1, p = .05) and instrumental social support (r = -.44, p = .05) were in the hypothesized directions, indicating that the use of social support is inversely related to the presence of PTSD symptoms, as hypothesized. Further, this study’s finding of moderation by emotional social support—indicating that the effect of disability on PTSD scores is smaller for those with higher levels of emotional social support--is also noteworthy. This corroborates with the earlier re- ported findings [see 58] that the availability of social support for people with disabilities bolsters one’s ability to cope adaptively with life’s crises. The finding that emotional social support statistically decreases the im- pact of disability on PTSD lev els suggests that therapeu- tic interventions that include interpersonal components, such as family and group counseling, can help facilitate the individual with a disability’s functioning and adapta- tion to the onset of a chronic medical condition. There is a range of empirically-based therapies, from cognitive behavior approaches to exposure therapies, which di- rectly target the PTSD symptomatology [for an overview  E. Martz et al. / Health 2 (2010) 332-341 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 339 of the range of treatments, see 64-67]. Yet, more com- prehensive strategies are needed, in order to address the complex traumatic reactions (e.g., “double PTSD” [13]) that may be experienced when a disability occurs in a war-zone. 9.1. Limitations The findings of this study must be interpreted with cau- tion. First, the generalizability of the findings obtained in this study is limited, because the data were drawn only from U.S. Vietnam veterans. King and King [59] pub- lished a detailed article critiquin g possible validity issu es related to research among Vietnam veterans. More re- cently, debates about calculating the PTSD rates from the NVVRS dataset have been published in several volumes of the Journal of Traumatic Stress. The condi- tions and uniqueness of the Vietnam war itself may have created differences in PTSD rates among veterans of various wars [68,69]. In addition, because this research was retrospective and used cross-sectional data, no causal patterns can be established. Further, the disability variab le was based on a single, self-reported item that did not encompass the wide range of possible disability definitions; yet, in this secondary data analysis, the researchers determined it as the best representation of a war injury with permanent consequences, i.e. disability. Finally, while the percent- age of variance explained in PTSD was notable (67%), unexplained variance still exists, which means that vari- ables not included in this study also are influencing PTSD levels. 10. CONCLUSIONS The results of this study provide unique information contributing to the knowledge about PTSD, which has been generated by the decades of research using data from the NVVRS and other sources. The present re- search examined whether disability predicted PTSD (while controlling for specific variables), in addition whether social support and coping were modifiers of that association; these two issues had not yet been studied in previous research using the N VVR S data. As expected, medical conditions or disabilities may be one source of the veterans’ PTSD. The findings clarified that emotional social support and problem-solving cop- ing both decrease the impact of perceived disability on PTSD levels. In view of such knowledge, psychosocial, therapeutic interventions may help to facilitate the indi- vidual with a disability’s functioning and adaptation to the onset of a permanent medical condition. Future re- search should test whether the findings of this study, which used a nationally representative data from the Vietnam era, can be replicated among veterans from the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. REFERENCES [1] Kulka, R.A., Schlenger, W.E., Fairbank, J.A., Hough, R.L., Jordan, B.K., Marmar, C.R. and Weiss, D.S. (1990) Trauma and the Vietnam war generation: Report of find- ings from the national Vietnam Veterans readjustment study. Brunner/Mazel Publishers, New York. [2] Kulka, R.A., Schlenger, W.E., Fairbank, J.A., Hough, R.L., Jordan, B.K., Marmar, C.R. and Weiss, D.S. (1990) The national Vietnam veterans readjustment study: Tables of findings and technical appendices. Brunner/Mazel, New York. [3] Solomon, Z. (1993) Combat stress reaction: The enduring toll of war. Plenum Press, New York. [4] Wilson, J.P. and Raphael, B., Eds. (1993) International handbook of traumatic stress syndromes. Plenum Press, New York. [5] Schnurr, P.P. and Green, B.L. (2004) Trauma and health: Physical health consequences of exposure to extreme stress. American Psychological Association, Washington DC. [6] Zatzick, D.F., Marmar, C.R., Weiss, D.S., Browner, W.S., Metzler, T.J., Golding, J.M., Stewart, A., Schlenger, W.E. and Wells, K.B. (1997) Posttraumatic stress disorder and functioning and quality of life outcomes in a nationally representative sample of male Vietnam veterans. Ameri- can Journal of Psychiatry, 154(12), 1690-1695. [7] Shontz, F.C. (1975) The psychological aspects of physical illness and disability. Macmillan Publishing Co., New York. [8] Wright, B.A. (1983) Physical disability: A psychosocial approach 2nd edition. New York: Harper and Row. [9] Martz, E. and Livneh, H. Eds. (2007) Coping with chronic illness and disability: Theoretical, empirical, and clinical aspects. Springer, New York. [10] Department of Veterans Affairs Office on Research and Development, National Institute of Mental Health, and US Army Medical Research and Materiel Command (2006) Mapping the landscape of deployment-related adjustment and mental disorders: A meeting summary of a working group to inform research. Rockville. http://www.research. va.gov/programs/OIF-OEF/deployment-related-adjustment -may06-report.pdf [11] Blanchard, E.B. and Hickling, E.J. (1997) After the crash: Assessment and treatment of motor vehicle accident sur- vivors. American Psychological Association, Washington, DC. [12] Miller, L. (1998) Shocks to the system: Psychotherapy of traumatic disability syndromes. W. W. Norton and Co., New York. [13] Radnitz, L.C., Schlein, S.I., Walczak, S., Broderick, P.C., Binks, M., Tirch, D.D., Willard, J., Perez-Strumolo, L., Festa, J., Lillian, B.L., Bockian, N., Cytryn, A., and Green, L. (1995) The prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder in veterans with spinal cord injury. SCI Psychosocial Process, 8, 145-149. [14] Alter, C.L., Pelcovitz, D., Axelrod, A., Goldenberg, B., Harris, H., Meyers, B., Grobois, B., Mandel, F., Septimus, A. and Kaplan, S. (1996) Identification of PTSD in cancer survivors. Psychosomatics, 37(2), 137-143.  E. Martz et al. / Health 2 (2010) 332-341 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 340 [15] Breslau, N. and Davis, G.C. (1992) Posttraumatic stress disorder in an urban population of young adults: Risk factors for chronicity. American Journal of Psychiatry, 49(5), 671-675. [16] Martz, E. (2005) Associations of posttraumatic stress levels with demographic, disability-related, and trauma- related variables among individuals with spinal cord inju- ries. Rehabilitation Psychology, 50(2), 149-157. [17] Martz, E., Birks, K., and Blackwell, T. (2005) The predic- tion of posttraumatic stress levels by depression among veterans with disabilities. Journal of Rehabilitation, 71(1), 56-61. [18] O’Donnell, M.L., Creamer, M., Bryant, R.A, Schnyder, U., and Shalev, A. (2003) Posttraumatic disorders following injury: An empirical and methodological review. Clinical Psychology Review, 23, 587-603. [19] Epstein, R.S. (1993) Avoidant symptoms cloaking the diagnosis of PTSD in patients with severe accidental in- jury. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 6(4), 451-458. [20] Jaspers, J.P. (1998) Whiplash and posttraumatic stress disorder. Disability and Rehabilitation, 20(11), 397-404. [21] Shalev, A.Y. (1992) Posttraumatic stress disorder among injured survivors of a terrorist attack: Predictive value of early intrusion and avoidance symptoms. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 180(8), 505-509. [22] Shalev, A.Y., Peri, T., Canetti, L., and Schreiber, S. (1996) Predictors of PTSD in injured trauma survivors: A pro- spective study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 153(2), 219-225. [23] Ursano, R.J., Fullerton, C.S., Epstein, R.S., Crowley, B., Kao, T., Vance, K., Craig, K.J., Dougall, A.L., and Baum, A. (1999) Acute and chronic posttraumatic stress disorder in motor vehicle accident victims. American Journal of Psychiatry, 156(4), 589-595. [24] Helzer, J.E., Robins, L.N., and McEvoy, L. (1987) Post- traumatic stress disorder in the general population. The New England Journal of Medicine, 317(26), 1630-1634. [25] Buydens-Branchey, L., Noumair, D., and Branchey, M. (1990) Duration and intensity of combat exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder in Vietnam veterans. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 178(9), 582-587. [26] Martz, E. and Cook, D. (2001)Physical impairments as risk factors for the development of posttraumatic stress disorder. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 44(4), 217-221. [27] Delimar, D. and Sivik, T. (1995) The effect of different traumatic experiences on the development of posttrau- matic stress disorder. Military Medicine, 160(12), 635- 639. [28] Martz, E. (2005) Associations of posttraumatic stress levels with demographic, disability-related, and trauma- related variables among individuals with spinal cord inju- ries. Rehabilitation Psychology, 50(2), 149-157. [29] Kaplan, M.S., Huguet, N., McFarland, B.H., and Newsom, J.T. (2007) Suicide among male veterans: A prospective population-based study. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 61, 619-624. [30] Terr, L.C. (1991) Childhood traumas: An outline and overview. American Journal of Psychiatry, 148(10), 10-20. [31] Wolfe, J., Keane, T.M. and Young, B.L. (1996) From sol- dier to civilian: Acute adjustment patterns of returned Persian gulf veterans In R J Ursano and A E Norwood Eds, Emotional aftermath of the Persian gulf war: Veterans, families, communities, and nations, American Psychiatric Press, Washington, DC, 477-499. [32] Suvak, M.K., Vogt, D.S., Savarese, V.W., King, L.A. and King, D.A. (2002) Relationship of war-zone coping stra- tegies to long-term general life adjustment among Viet- nam Veterans: Combat exposure as a moderator variable. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(7), 974- 985. [33] Martz, E., Bodner, T. and Livneh, H. (2009) Coping as a moderator between disability and adaptation among Viet- nam theater veterans. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 65(1), 94-112. [34] Mikulincer, M. and Solomon, Z. (1989) Causal attribution, coping strategies, and combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. European Journal of Personality, 3, 269-284. [35] Sutker, P.B., Davis, J.M., Uddo, M. and Ditta, S.R. (1995) War zone stress, personal resources, and PTSD in Persian Gulf war returnees. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 104(3), 444-452. [36] Wolfe, J., Keane, T.M., Kaloupek, D.G., Mora, C.A. and Wine, P. (1993) Patterns of positive readjustment in Vietnam combat veterans. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 6( 2), 179-193. [37] Zeidner, M. and Ben-Zur, H. (1994) Individual differences in anxiety, coping, and posttraumatic stress in the after- math of the Persian Gulf War. Personality and Individual Differences, 16(3), 459-476. [38] Koenen, K.C., Stellman, J.M. and Stellman, S.D. (2003) Risk factors for course of posttraumatic stress disorder among Vietnam veterans: A 14-year follow-up of Ameri- can legionnaires. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psy- chology, 71, 980-986. [39] Lawrence, J.W. and Fauerbach, J.A. (2003) Personality, coping, chronic stress, social support, and PTSD symp- toms among adult burn survivors. Journal of Burn Care and Rehabilitation, 24, 63-72. [40] Desmond, D.M. and MacLachlan, M. (2006) Coping strategies as predictors of psychosocial adaptation in a sample of elderly veterans with acquired lower limb am- putations. Social Science and Medicine, 62, 208-216. [41] Hanson, S., Buckelew, S.P., Hewett, J. and O'Neal, G. (1993) The relationship between coping and adjustment after spinal cord injury: A 5-year follow-up study. Reha- bilitation Psychology, 38(1), 41-51. [42] Livneh, H. and Wilson, L.M. (2003) Coping strategies as predictors and mediators of disability-related variables and psychosocial adaptation: An exploratory investigation. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 46(4), 194-208. [43] Moore, A.D. and Stambrook, M. (1992) Coping strategies and locus of control following traumatic brain injury: Re- lationship to long-term outcome. Brain Injury, 6, 89-94. [44] Moore, A.D. and Stambrook, M. (1994) Coping following traumatic Brain Injury: Derivation and validation of TBI sample Ways of Coping-Revised subscales. Canadian Journal of Rehabilitation, 7, 193-200. [45] Lazarus, R.S. and Folkman, S. (1984) Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer. [46] Thoits, P.A. (1986) Social support as coping assistance. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 54(4), 416-423. [47] Fontana, A. and Rosenheck, R. (1994) Posttraumatic  E. Martz et al. / Health 2 (2010) 332-341 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 341 stress disorder among Vietnam theater veterans: A causal model of etiology in a community sample. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 182(12), 677-684. [48] Fontana, A. and Rosenheck, R. (1999) A model of war-zone stressors and posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 12(1), 111-126. [49] King, D.W., King, L.A., Gudanowski, D.M., and Vreven, D.L. (1995) Alternative representations of war zone stressors: Relationships to posttraumatic stress disorder in male and female Vietnam veterans. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 104(1), 184-196. [50] King, D.W., King, L.A., Foy, D.W., and Gudanowski, D.M. (1996) Prewar factors in combat-related posttrau- matic stress disorder: Structural equation modeling with a national sample of female and male Vietnam veterans. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64( 3), 520-531. [51] King, D.W., King, L.A., Foy, D.W., Keane, T.M., and Fairbank, J.A. (1999) Posttraumatic stress disorder in a national sample of female and male Vietnam veterans: Risk factors, war-zone stressors, and resilience-recovery variables. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 108(1), 164-170. [52] Weiss, D.S., Marmar, C.R., Schlenger, W.E., Fairbank, J.A., Jordan, B.K., Hough, R.L., and Kulka, R.A. (1992) The prevalence of lifetime and partial post-traumatic stress disorder in Vietnam theater veterans. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 5(3), 365-376. [53] Keane, T.M., Caddell, J.M., and Taylor, K.L. (1988) Mis- sissippi scale for combat-related posttraumatic stress dis- order: Three studies in reliability and validity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56, 85-90. [54] Folkman, S. and Lazarus, R.S. (1980) An analysis of cop- ing in a middle-aged community sample. Journal of Heal- th and Social Behavior, 21, 219-239. [55] Muthén, L.K. and Muthén, B.O. (2009) MPlus users guide. http://www.statmodel.com/ugexcerpts.shtml [56] Aiken, L. and West, S. (1991) Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage Newbury, Park. [57] Kennedy, P., Lowe, R., Grey, N., and Short, E. (1995) Traumatic spinal cord injury and psychological impact: A cross-sectional analysis of coping strategies. British Jour- nal of Clinical Psychology, 34, 627-639. [58] Moos, R.H. and Holahan, C.J. (2007) Adaptive tasks and methods of coping with illness and disability. In Martz, E. and Livneh, H. Eds., Coping with chronic illness and disability: Theoretical, empirical, and clinical aspects. Springer, New York, 107-126. [59] King, D.W. and King, L.A. (1991) Validity issues in re- search on Vietnam veteran adjustment. Psychological Bul- letin, 109(1), 107-124. [60] Lazarus, R.S. (1966) Psychological stress and the coping process. McGraw-Hill, New York [61] Lazarus, R.S. (1991) Emotion and adaptation. Oxford, New York [62] Kennedy, P. and Duff, J. (2001) Coping effectively with spinal cord injury. Stoke Mandeville Hospital NHS Trust, United Kingdom. [63] Kennedy, P., Duff, J., Evans, M. and Beedie, A. (2003) Coping effectiveness training reduces depression and anxiety following traumatic spinal cord injuries. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 42, 41-52. [64] Wilson, J.P. and Raphael, B. (Eds.) (1993) International handbook of traumatic stress syndromes. Plenum Press, New York. [65] Shalev, A., Yehuda, R. and McFarlane, A. (Eds.) (2000) International handbook of human response to trauma. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, New York. [66] Friedman, M.J., Keane, T.M., Resick, P.A. (Eds.) (2007) Handbook of PTSD: Science and practice. Guilford Press, New York. [67] Institute of Medicine of the National Academies (2008) Treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder: An assessment of the evidence. http://books.nap.edu/openbook.php?re- cord_id=11955andpage=R1 [68] McCranie, E.W. and Hyer, P. (2000) Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in Korean conflict and World War II combat veterans seeking outpatient treatment. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 13, 427-439. [69] Page, W.F., Engdahl, B.E., and Eberly, R.E. (1997) Per- sistence of PTSD in former prisoners of war. In Fullerton, C.S. and Ursano, R.J. (Eds.), Posttraumatic stress disorder: Acute and long-term responses to trauma and disaster. American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC, US, 147-158. |