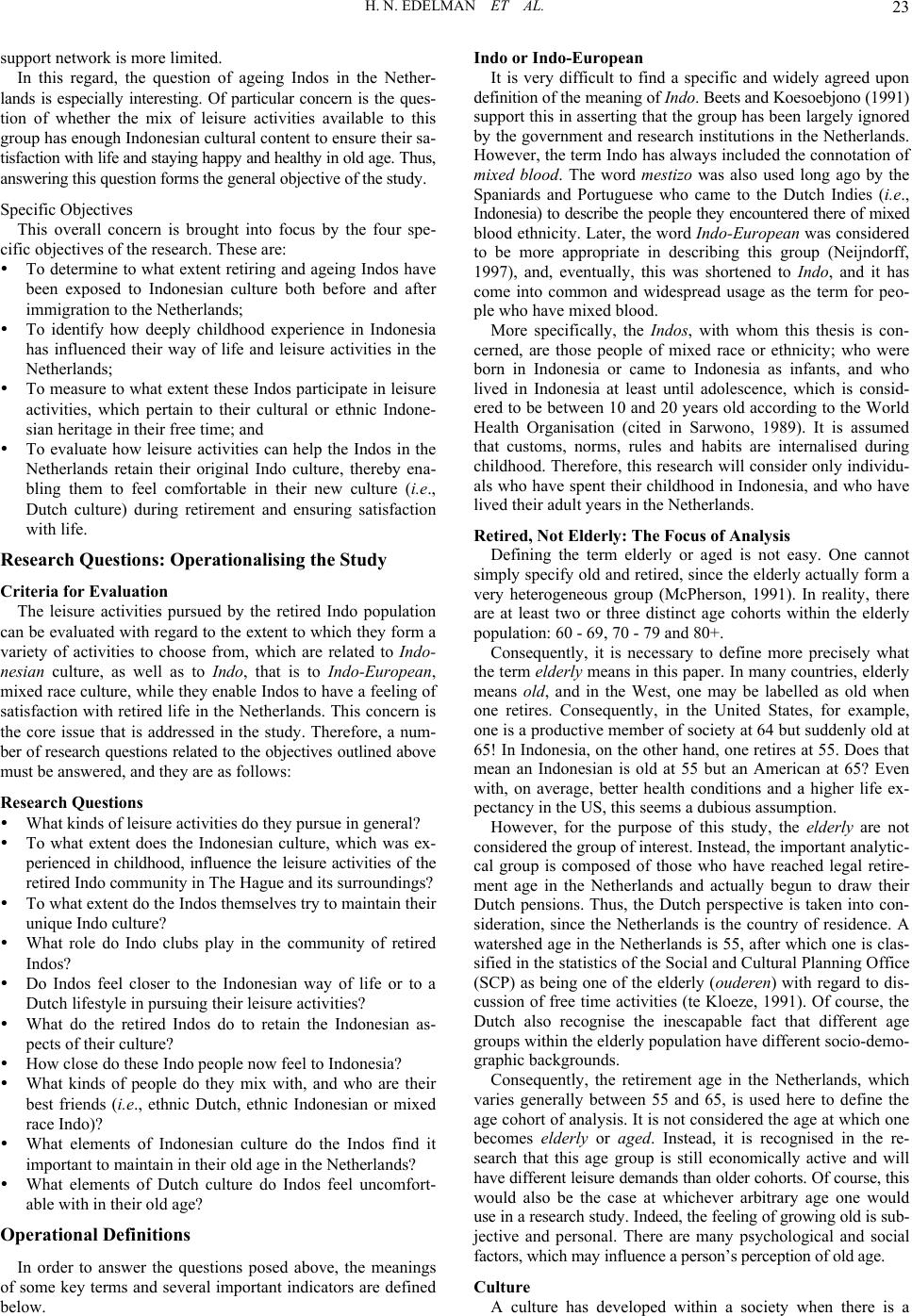

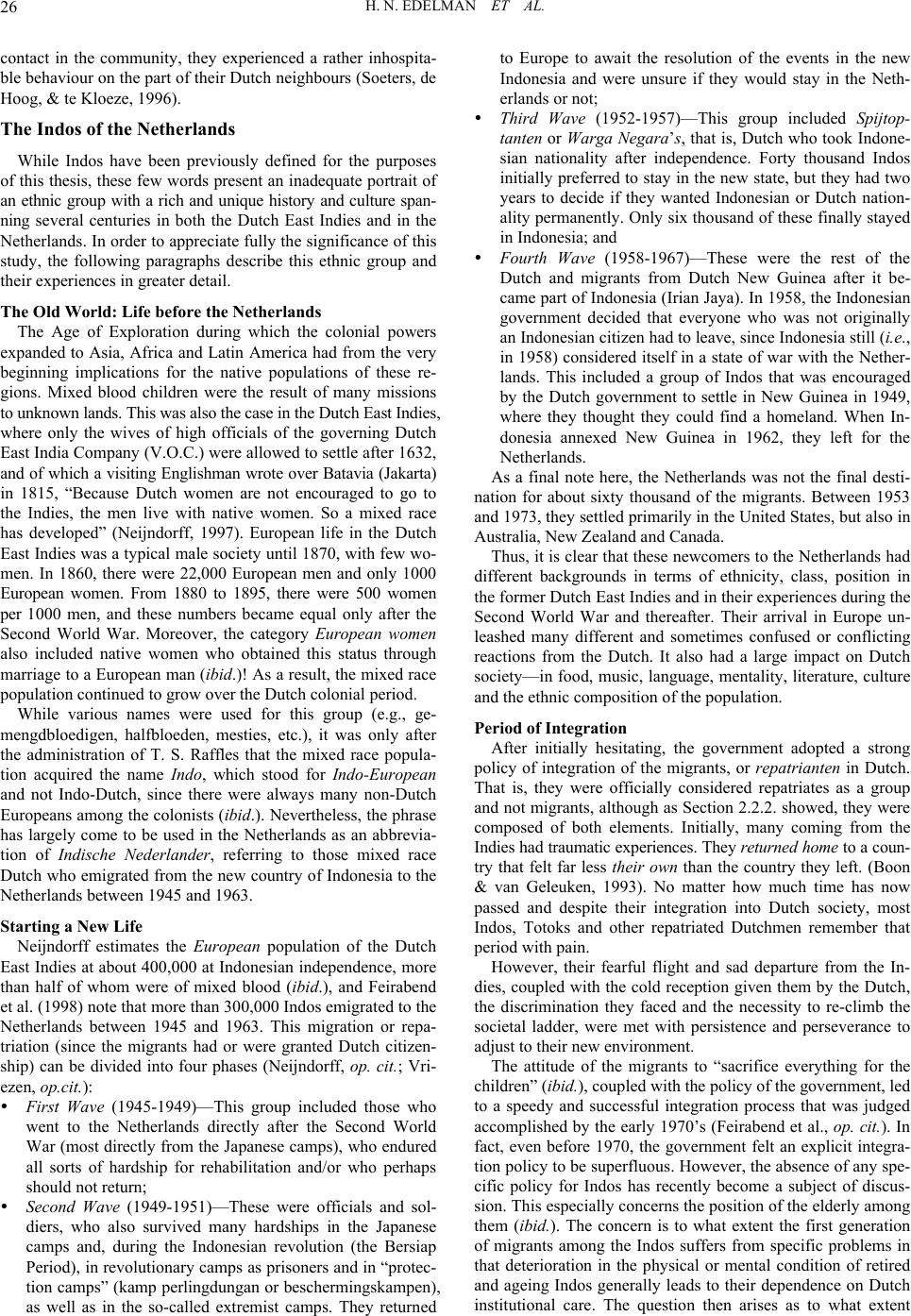

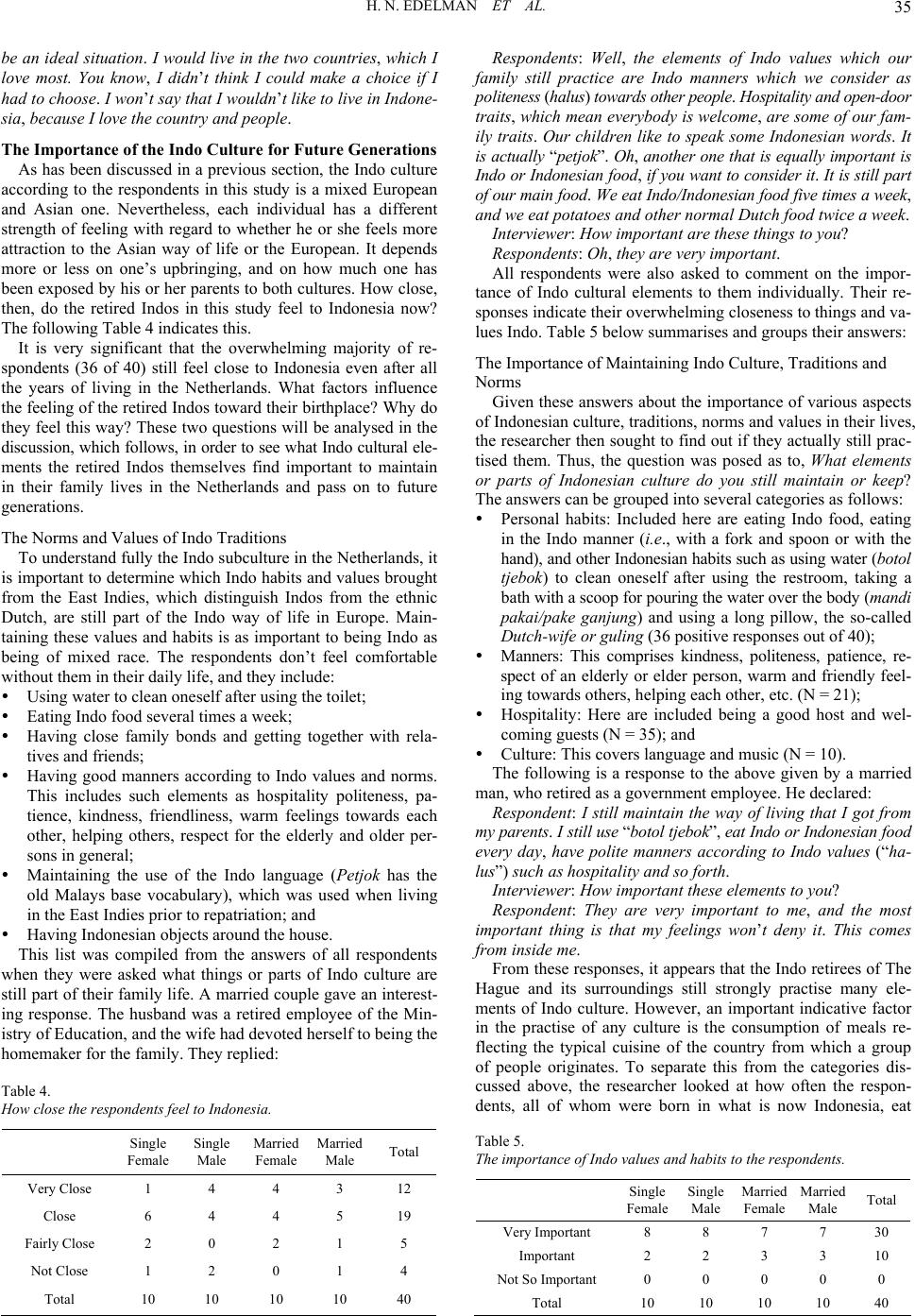

Advances in Applied Sociology 2011. Vol.1, No.1, 22-47 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. DOI:10.4236/aasoci.2011.11003 Leisure among the Retired Indos of the Hague Henny N. Edelman1, David J. Edelman2 1Putrie Consulting, Cincinnati, USA; 2School of Planning, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, USA. Email: david.edelman@uc.edu Received November 16th, 2011; revised December 21st, 2011; accepted December 28th, 2011. The ethnic mixture in Europe has been changing rapidly since the end of World War II, and many of these im- migrant groups are now reaching retirement. The Netherlands is one of the countries affected in this way. This study focuses on mixed race people (Indos) originating in the former Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia) and re- siding in The Hague and its surrounding area. Their situation is relevant to other immigrant groups in other European countries. There are several important issues that are studied here with regard to their leisure from which a typology of Indo leisure lifestyles is developed. These issues include :1) how this group is able to avail itself of leisure activities with which its members feel comfortable during retirement and old age; 2) whether this group has integrated itself completely into the host society and feels happy in its social life; 3) whether the lei- sure activities of retired Indos are a way for them to keep healthy mentally and physically, thereby leading to satisfaction with life; and 4) how this particular group of people feels about its unique identity and culture after many years of living in the Netherlands. Keywords: Leisure and the Immigrant Elderly , Indos in Retirement, Europe and Its Aging Ethnic Im migrants Introduction Problem Setting Background The subject of leisure and recreation for the elderly is an in- creasingly important topic in the Netherlands as those adults born just after the end of World War II begin to reach retire- ment age. Both the Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS) and the Royal Institute for Public Health and Environmental Hygiene (RIVM) have been studying the implications of this greying of the Dutch population (de Volkskrant, 3 January 1998). These, so called Baby Boomers are wealthier, healthier and more in- dependent than past generations, and it can be expected that their requirements for leisure will be affected by these factors (de Volksrant, 19 December 1997). Thus, these new circum- stances will affect the lifestyle and leisure activities of Dutch retirees in the future, who are expected to have different de- mands than those of the present. This study, however, focuses on a particular subgroup of Dutch retirees, the members of which are now beginning to cease working and who only partially fit the profile of the dominant culture. That is, this study is centred on retired people residing in the Netherlands who were not born in the country or who have non-Dutch parents. The question is how are they able to avail themselves of leisure as they age and reach retirement. Of primary concern here are the questions of whether the members of this group have integrated themselves into local society and feel happy in their social lives, and whether their leisure active- ties are a way for them to keep themselves healthy mentally and physically. Another item of concern is how important the mem- bers of the group feel their unique identity and culture is to them. These are important issues if, as is assumed for this research, they are not as wealthy or “Dutch” enough, in comparison to native ethnic Dutch, to have their needs met by the social ser- vices provided in their local community or by the private sector. It is a question of public policy how to accommodate these needs. In order to consider the issues related to this concern, the study concentrates on a specific section of this subgroup. These are the retired Indos, or mixed race immigrants from the former Dutch East Indies, residing in the Netherlands. They form a large non-white ethnic group numbering 440,330 in 1996 (Wolt - ers-Noordhoff Atlas, 19 97), which has been present in the coun- try for several generations. A significant number of individuals in this group are soon to reach retirement. The Hague metro- politan area has been chosen as the place of analysis for several reasons. First, ac cording to Dutch statistic s, the city has an above average percentage of elderly (65+) residents 17.2% versus the national municipal average of 12.82%, while the provincial percentage for South Holland of 13.8% is slightly above the national average of 13.35%. In addition, the province has the highest number of people in the Netherlands who were born in Indonesia and the former Dutch East Indies. 113,624 residents of this type represent 26% of all in the country (440,330). In The Hague itself, 5.5% of the population belongs to this group, while the national municipal average is only 1.97% (ibid.). With the changing ethnic mix, or what is called here the browning of the populations of European countries due to im- migration, and with the greying of those populations, the ques- tion of the mix of leisure activities undertaken by the first gen- eration immigrant elderly becomes increasingly important. Where and how, then, can they feel comfortable to pursue leisure, which is consistent with their own habits and customs? This is an espe- cially difficult matter when those migrants are of mixed race or ethnicity, and also not fully integrated into the local society. Research Objectives General Objective The ability of the first generation of any immigrant group to accept the culture and habits of their new homeland, as well as the acceptance of that group by the people among whom they now reside, are important factors for the immigrant group’s leisure. This situation reaches a critical phase when the immi- grants reach retirement. All retirees face a lifesty le change when they cease working, but this adjustment is more difficult for immigrants who are not fully integrated because their social  H. N. EDELMAN ET AL. 23 support network is more limited. In this regard, the question of ageing Indos in the Nether- lands is especially interesting. Of particular concern is the ques- tion of whether the mix of leisure activities available to this group has enough Indonesian cultural content to ensure their sa- tisfaction with life and staying happy and healthy in old age. Thus, answering this question forms the general objective of the study. Specific Objectives This overall concern is brought into focus by the four spe- cific objectives of the research. These are: To determine to what extent retiring and ageing Indos have been exposed to Indonesian culture both before and after immigration to the Ne t her lands; To identify how deeply childhood experience in Indonesia has influenced their way of life and leisure activities in the Netherlands; To measure to what extent these Indos participate in leisure activities, which pertain to their cultural or ethnic Indone- sian heritage in their free time; and To evaluate how leisure activities can help the Indos in the Netherlands retain their original Indo culture, thereby ena- bling them to feel comfortable in their new culture (i.e., Dutch culture) during retirement and ensuring satisfaction with life. Research Questions: Operationalising the Study Criteria for Evaluation The leisure activities pursued by the retired Indo population can be evaluated with regard to the extent to which they form a variety of activities to choose from, which are related to Indo- nesian culture, as well as to Indo, that is to Indo-European, mixed race culture, while they enable Indos to have a feeling of satisfaction with retired life in the Netherlands. This concern is the core issue that is addressed in the study. Therefore, a num- ber of research questions related t o the objectives outlined above must be answered, and they are as follows: Research Questions What kinds of leisure activities do they pursue in general? To what extent does the Indonesian culture, which was ex- perienced in childhood, influence the leisure activities of the retired Indo commun i t y in The Hague a n d i t s surroundings? To what extent do the Indos themselves try to maintain their unique Indo culture? What role do Indo clubs play in the community of retired Indos? Do Indos feel closer to the Indonesian way of life or to a Dutch lifestyle in pursuing their leisure activities? What do the retired Indos do to retain the Indonesian as- pects of their culture? How close do these Indo people now feel to Indonesia? What kinds of people do they mix with, and who are their best friends (i.e., ethnic Dutch, ethnic Indonesian or mixed race Indo)? What elements of Indonesian culture do the Indos find it important to maintain in their old age in the Netherlands? What elements of Dutch culture do Indos feel uncomfort- able with in their old age? Operational D e fi ni tio ns In order to answer the questions posed above, the meanings of some key terms and several important indicators are defined below. Indo or Indo-European It is very difficult to find a specific and widely agreed upon definition of the meaning of Indo. Beets and Koe soebjon o (1 991) support this in asserting that the group has been largely ignored by the government and research institutions in the Netherlands. However, the term Indo has always included the connotation of mixed blood. The word mestizo was also used long ago by the Spaniards and Portuguese who came to the Dutch Indies (i.e., Indonesia) to describe the people they encountered there of mixed blood ethnicity. Later, the word Indo-European was considered to be more appropriate in describing this group (Neijndorff, 1997), and, eventually, this was shortened to Indo, and it has come into common and widespread usage as the term for peo- ple who have mixed blood. More specifically, the Indos, with whom this thesis is con- cerned, are those people of mixed race or ethnicity; who were born in Indonesia or came to Indonesia as infants, and who lived in Indonesia at least until adolescence, which is consid- ered to be between 10 and 20 years old according to the World Health Organisation (cited in Sarwono, 1989). It is assumed that customs, norms, rules and habits are internalised during childhood. Therefore, this research will consider only individu- als who have spent their childhood in Indonesia, and who have lived their adult years in the Netherlands. Retired, Not Elderly: The Focus of Analysis Defining the term elderly or aged is not easy. One cannot simply specify old and retired, since the elderly actually form a very heterogeneous group (McPherson, 1991). In reality, there are at least two or three distinct age cohorts within the elderly population: 60 - 69, 70 - 79 and 80+. Consequently, it is necessary to define more precisely what the term elderly means in this paper. In many countries, elderly means old, and in the West, one may be labelled as old when one retires. Consequently, in the United States, for example, one is a productive member of society at 64 but suddenly old at 65! In Indonesia, on the other hand, one retires at 55. Does that mean an Indonesian is old at 55 but an American at 65? Even with, on average, better health conditions and a higher life ex- pectancy in the US, this seems a dubious assumption. However, for the purpose of this study, the elderly are not considered the group of interest. Instead, the important analytic- cal group is composed of those who have reached legal retire- ment age in the Netherlands and actually begun to draw their Dutch pensions. Thus, the Dutch perspective is taken into con- sideration, since the Netherlands is the country of residence. A watershed age in the Netherlands is 55, after which one is clas- sified in the statistics of the Social and Cultural Planning Office (SCP) as being one of the elderly (ouderen) with regard to dis- cussion of free time activities (te Kloeze, 1991). Of course, the Dutch also recognise the inescapable fact that different age groups within the elderly population have different socio-demo- graphic backgrounds. Consequently, the retirement age in the Netherlands, which varies generally between 55 and 65, is used here to define the age cohort of analysis. It is not considered the age at which one becomes elderly or aged. Instead, it is recognised in the re- search that this age group is still economically active and will have different leisure demand s than older cohorts. Of course, thi s would also be the case at whichever arbitrary age one would use in a research study. Indeed, the feeling of grow ing old is sub- jective and personal. There are many psychological and social factors, which may influence a person’s perception of old age. Culture A culture has developed within a society when there is a  H. N. EDELMAN ET AL. 24 similarity in perception of certain things among its individual members, and when they share a way of life, values, norms, be- liefs, customs, knowledge, language, music, songs, dress, litera - ture, laws, ceremonies, and so forth. McPherson (1990) calls these aspects the non-material and material elements wherein culture provides a symbolic order and a set of shared meanings to social life. For the purpose of this study, a culture is defined when indi- viduals share non-material elements such as values, norms, cus- toms, knowledge, beliefs, as well as the material elements of life, such as eating habits, a clothing or dress code, arts, history, lan- guage, literature, music, folklore, traditional ceremonies and laws. Leisure and Recreation The terms leisure and recreation are often used interchangea- bly. However, in the academic and professional literature, they have different meanings. It is, therefore, necessary to define these terms for the purpose of the proposed research. A clear distinction is made by Leitner and Leitner (1996), who define leisure as, “··· free or unobligated time, time during which work, life-sustaining functions, and other obligatory activities are not performed.” Recreation, on the other hand, is defined as “··· activity conducted during leisure, usually for the purpose of enjoyment”. Of course, many aspects of leisure and recreation have been defined through the different professional orientation of a par- ticular discipline. For example, Kelly sees leisure from the so- ciological perspective. Thus, he sees leisure as a product of the social system and embedded in c ulture and its institutional struc- tures (Borgatta & Borgatta, 1991). The observation of Iso-Ahola (1997), on the other hand, is that for leisure to exist, one has to be in control of one’s actions and have a sense of freedom to pursue willingly a given activity. Without belabouring this point further, leisure here is con- sidered as the time withi n which fre ely chosen discret iona ry ac- tivities (i.e., recreational activities) of an individual are pursued for enjoyment and pleasure within the norms of society. Thus, the basic definition of Leitner and Leitner is considered within the limits imposed by Kelly and Is o -A h o la . Scope and Research Methodology The research in this study was conducted in The Hague and its surroundings by involving the local Indo community within the boundarie s of the chosen resea rch areas. This st udy addresse s social and well being issues through the analysis of leisure ac- tivities available in The Hague and its suburbs. It is necessary to specify carefully the scope of this research as follows: It covers the current availability of leisure activities, as well as how to plan and develop future leisure programs, which will improve and benefit the well being of the local Indo - elderly specifically and the whole Indo community in gen- eral; It considers the relationships between local governments and the Indo community in keeping the Indo culture and the relationship of the community to Indonesian culture alive; and It also contributes to ensuring the continuity of ethnic lei- sure activities to bridge the gap between the programs of local leisure centres and the needs of the Indo population. The above issues are addressed in the study through the de- tailed discussion of leisure activities with several local Indo clubs and a sample group of forty retired Indo residents (i.e., ten single men, ten single women and ten couples, the male and female partners of which are interviewed separately) in The Ha- gue and its surroundings. The respondents were inte rviewed using in-depth, open-ended questions focusing on certain issues. This allowed the respon- dents to interact with the researcher and explain their answers fully. The interviews yielded information, which was then fol- lowed up in other interviews and further research. A tape re- corder was used in all instances. In addition to interviewing retired Indo respondents, some key people, including academics, researchers and government officials, who have considerable knowledge about the subject under study, were also consulted. They contributed to the work by discussing important issues, which are related to the social and cultural aspects of the research and the historical back- ground of the Indo people. Virtually all interviews (i.e., 39 out of 40) were conducted at the respondents’ residences, so that during the interviews the researcher could observe the way of life of the respondents di- rectly. For example, how the respondents decorate their homes, their eating habits and what their domestic toilet habits are (i.e., whether they use water or paper after using the toilet) provide significant information about whether they feel closer to Indo- nesian or European culture. Each respondent was interviewed, on average, for two to three hours in the language with which they felt most comfortable. Dutch, Indonesian and English were all used. The researcher interviewed the partners of a couple separately, and right after each other, so that interference of one spouse on the other in answering questions was minimised. The respondents sometimes invited the researcher to have lunch in their homes or have snacks with tea/coffee over the long inter- view. This shows that hospitality has remained a part of Indo culture, which will be discussed in detail in Section 4. Sampling Technique The target population consisted of those Indo residents who reside within The Hague and its surroundings. Due to the diffi- culties of constructing a sample population, the so-called snow- ball effect method was used. With this method, the population to be researched was obtained through first consulting impor- tant and established key source people who work at universities, research institutes, government institutions, the media and at registered or otherwise recognised Indo organisations. Thus, the starting point of the snowball effect to obtain a research sample was to identify very reliable sources for the initial consultations. This was done by consulting academics at the University of Leiden, who are experts on Indonesian history. This includes, especially, the project co-ordinator of the Oral History Project on Indonesia (Stichting Mondelinge Geschiedenis Indonesie). Their recommendations led to leaders of various Indo founda- tions (such as Pelita) and government officials (e.g., from the Dutch census bureau, the CBS). In parallel to this, contacts of the primary researcher among her friends in the Indo commu- nity in The Hague led to recommendations of clubs to visit and Indo representatives to talk to. They suggested individuals who might fit the research profile. The researcher then t alked to them. Some of them were appropriate and others not, but all sug gested further people to talk to. The variety in the background s of these resource persons and initial contacts in the Indo community led to different backgrounds among the target samples in this study. The population selected in this way is more likely to yield a random sample by matching people to the sampling character- istics and conditions, which are determined by the operational definitions. The required conditions for those, who were inter- viewed as subjects in this study, were that each respondent must:  H. N. EDELMAN ET AL. 25 Have mixed blood characterising him/her as Indo; Have been born in Indonesia or moved to Indonesia as an infant during the era of the Dutch Indies; Have spent at least her/his childhood up to adolescence in Indonesia; Have arrived in the Netherlands after World War II; Be a retiree at the present time (i.e., above 55 years old); and Live in The Hague and its surroundings. Those people who were identified as fulfilling the above conditions (60) were put into an initial research sample, which was then controlled to ensure homogeneity of the sample (or sub-samples) in t erms of socio-demographic background( s). Fur- thermore, an equal number of men (20) and women (20) were selected to be studied. Lastly, both married and currently single (i.e., those who never married, are widowed or are divorced) individuals were selected, so that the final sample of forty was composed of ten single men (4 widowed, 3 divorced and 3 ne- ver married), ten single women (9 widowed, 1 divorced and 0 never married) and ten married couples. Partners were inter- viewed separately, as well as directly after each other, to elimi- nate the effects of a dominant partner on the responses of the spouse. The reason for interviewing both single and married retirees was to determine if there were significant differences in their leisure due to their marital status. The data/information were collected by various methods. Anthropological approaches were used to gather information, namely by using observation, in-depth interviewing and parti- cipant observation. These approaches have been chosen in or- der to collect a great deal of detailed information from the rela- tively limited number of respondents in this study. Data Analysis Each answer from a respondent was analysed and notes taken. The use of a tape recorder proved essential in allowing the re- searcher to review each answer and each interview repeatedly, and to recapture the nature of a particular interview weeks and even months after it took place. The researchers then put to- gether the responses to each question and reread interview ob- servations and post-interview notes before drawing any conclu- sion from the specific pattern of answers. Because of the nature of the interview procedure, by which the respondents gave long and detailed answers to each question, the primary researcher had to skip around the recordings quite a bit to filter out re- peated information and draw inferences and deductions from several answers given to questions at widely separated points in an interview. Sometimes, re spondents referred back to previous questions in answering a later question or during a break in the interview for refreshments. Characteristics, History and Background of the Study Population In the Netherlands, no special attention was paid to the im- migrant, ethnic elderly by the government before 1985 (Vriezen, 1993). In that year, an official nota (policy paper similar to a British white paper) on the ethnic elderly appeared entitled Ou- deren uit ethnische groepen. This was the first time the gov- ernment connected the two subject areas of ouderen (the elderly) and minderheden (minorities). The paper was intended as an inventory of minority groups and what was known over their living conditions (ibid.). Naturally, the Indo group was included here. Government policy regarding the point of departure of the minority elderly, however, was no different than for the ethnic Dutch. The two-track policy of independence and participation (in all aspects of social life) was the same for all. It wasn’t until the nota Ouderenbeleid 1990-1991 that it was mentioned in Dutch policy that the traditional c are for the Dutch elderly might not be as suitable for other ethnic groups as had been assumed. In order to end problems such as isolation among these elderly, it was recognised that it had become necessary to initiate new information, research and other projects specifically targeted at them (ibid.). Moreover, despite the strong role ethnicity has in ageing, as the Indo population continues to grow older, families will be less able to provide this social support. In the year 2000, there will be around 27,000 Indo men and women, who are 75 years old or older. Some will need to go to nursing homes, and the preferred homes are those that cater to their ethnicity. It has been estimated that in 2000 there will be a need for between 575 and 863 places in Indo nursing homes. In The Hague and its surroundings, above all, the need for an Indo home is great- est (Rijkschroeff, The, & Wu, 1993). The Elderly and Their Leisure in the Netherlands Before proceeding to an historical analysis of the Indo com- munity in the Netherlands in order to set the stage for the ana- lysis of the leisure activities of its aged and retired members, it is first necessary to describe the leisure of the same age cohort among the host Dutch population. This highlights the situation that the Indo elderly face as partially assimilated immigrants with a unique culture. The Leisure Patterns of the Elderly in the Netherlands To get a first impression of how the Dutch elderly spend their leisure time, the results of nation-wide research conducted by the Social and Cultural Planning Office between 1975 and 1985 are significant (te Kloeze, 1990). These differentiate the retired from the working population. In terms of time spent on leisure, the retired spent between 63 and 67 hours each week on leisure as opposed to the employed, who spent between 37 and 42 hours. However, they went out less than the employed, and they, along with the unemployed and the disabled (the statistics are not disaggregated), spent more time on contacts within the family circle, electronic media, reading, resting, recreation out- side the home, hobbies, sport and games, the care of plants and animals and do-it-yourself activities (ibid.). Thus, the Dutch elderly appear to have more sedentary leisure than their work- ing countrymen do. Another significant aspect of leisure for the elderly in the Netherlands is the point that most leisure takes place in or near the home. This means the neighbourhood takes on great signi- ficance for the Dutch elderly. Their social networks within the neighbourhood are, therefore, important to limiting social isola- tion in old age (Thissen, 1992). Thus, in considering the leisure of the Indo elderly in the Netherlands, the attitude of the neigh- bourhood’s residents to them, as well as their feeling towards their Dutch neighbours, becomes significant. In a study of the integration of Turkish families into a Dutch neighbourhood in Arnhem through recreational activities, it was found that most of the Turkish families indicated that they seek integration into Dutch society at the local level. Nevertheless, they retain a substantial amount of elements from their own culture and do not adopt many aspects of Dutch society (te Kloeze, 1998). Thus, after three generations, they appear to remain predominantly oriented toward their own cultural group. Moreover, although the respondents in the research expressed a need for more social  H. N. EDELMAN ET AL. 26 contact in the community, they experienced a rather inhospita- ble behaviour on the part of their Dutch neighbours (Soeters, de Hoog, & te Kloeze, 1996). The Indos of the Netherlands While Indos have been previously defined for the purposes of this thesis, these few words present an inadequate portrait of an ethnic group with a rich and unique history and culture span- ning several centuries in both the Dutch East Indies and in the Netherlands. In order to appreciate fully the significance of this study, the following paragraphs describe this ethnic group and their experiences in greater detail. The Old World: Life before the Netherlands The Age of Exploration during which the colonial powers expanded to Asia, Africa and Latin America had from the very beginning implications for the native populations of these re- gions. Mixed blood children were the result of many missions to unknown lands. This was also the case in the Dutch East Indies, where only the wives of high officials of the governing Dutch East India Company (V.O.C.) were allowed to settle after 1632, and of which a visiting Englishman wrote over Batavia (Jakarta) in 1815, “Because Dutch women are not encouraged to go to the Indies, the men live with native women. So a mixed race has developed” (Neijndorff, 1997). European life in the Dutch East Indies was a typi cal male society until 1870, with few wo- men. In 1860, there were 22,000 European men and only 1000 European women. From 1880 to 1895, there were 500 women per 1000 men, and these numbers became equal only after the Second World War. Moreover, the category European women also included native women who obtained this status through marriage to a European man (ibid.)! As a result, the mixed race population continued to grow over the Dutch colonial period. While various names were used for this group (e.g., ge- mengdbloedigen, halfbloeden, mesties, etc.), it was only after the administration of T. S. Raffles that the mixed race popula- tion acquired the name Indo, which stood for Indo-European and not Indo-Dutch, since there were always many non-Dutch Europeans among the colonists (ibid.). Nevertheless, the phrase has largely come to be used in the Netherlands as an abbrevia- tion of Indische Nederlander, referring to those mixed race Dutch who emigrated from the new country of Indonesia to the Netherlands between 1945 and 1963. Starting a New Life Neijndorff estimates the European population of the Dutch East Indies at about 400,000 at Indonesian independence, more than half of whom were of mixed blood (ibid.), and Feirabend et al. (1998) note that more than 300,000 Indos emigrated to the Netherlands between 1945 and 1963. This migration or repa- triation (since the migrants had or were granted Dutch citizen- ship) can be divided into four phases (Neijndorff, op. cit.; Vri- ezen, op.cit.): First Wave (1945-1949)—This group included those who went to the Netherlands directly after the Second World War (most directly from the Japanese camps), who endured all sorts of hardship for rehabilitation and/or who perhaps should not return; Second Wave (1949-1951)—These were officials and sol- diers, who also survived many hardships in the Japanese camps and, during the Indonesian revolution (the Bersiap Period), in revolutionary camps as prisoners and in “protec- tion camps” (kamp perlingdungan or beschermingskampen), as well as in the so-called extremist camps. They returned to Europe to await the resolution of the events in the new Indonesia and were unsure if they would stay in the Neth- erlands or not; Third Wave (1952-1957)—This group included Spijtop- tanten or Warga Negara’s, that is, Dutch who took Indone- sian nationality after independence. Forty thousand Indos initially preferred to stay in the new state, but they had two years to decide if they wanted Indonesian or Dutch nation- ality permanently. Only six thousand of these finally stay ed in Indonesia; and Fourth Wave (1958-1967)—These were the rest of the Dutch and migrants from Dutch New Guinea after it be- came part of Indonesia (Irian Jaya). In 1958, the Indonesian government decided that everyone who was not originally an Indonesian citizen had to leave, since Indonesia still (i.e., in 1958) considered itself in a state of war with the Nether- lands. This included a group of Indos that was encouraged by the Dutch government to settle in New Guinea in 1949, where they thought they could find a homeland. When In- donesia annexed New Guinea in 1962, they left for the Netherlands. As a final note here, the Netherlands was not the final desti- nation for about sixty thousand of the migrants. Between 1953 and 1973, they settled primarily in the United States, but also in Australia, New Zealand and Can ada. Thus, it is clear that these newcomers to the Netherlands had different backgrounds in terms of ethnicity, class, position in the former Dutch East Indies and in their experiences during the Second World War and thereafter. Their arrival in Europe un- leashed many different and sometimes confused or conflicting reactions from the Dutch. It also had a large impact on Dutch society—in food, music, language, mentality, literature, culture and the ethnic composition of the population. Period of Integration After initially hesitating, the government adopted a strong policy of integration of the migrants, or repatrianten in Dutch. That is, they were officially considered repatriates as a group and not migrants, although as Section 2.2.2. showed, they were composed of both elements. Initially, many coming from the Indies had traumatic experiences. They returne d home to a coun- try that felt far less their own than the country they left. (Boon & van Geleuken, 1993). No matter how much time has now passed and despite their integration into Dutch society, most Indos, Totoks and other repatriated Dutchmen remember that period with pain. However, their fearful flight and sad departure from the In- dies, coupled with the cold reception given them by the Dutch, the discrimination they faced and the necessity to re-climb the societal ladder, were met with persistence and perseverance to adjust to their new environment. The attitude of the migrants to “sacrifice everything for the children” (ibid.), coupled with the policy of the government, led to a speedy and successful integration process that was judged accomplished by the early 1970’s (Feirabend et al., op. cit.). In fact, even before 1970, the government felt an explicit integra- tion policy to be superfluous. However, the absence of any spe- cific policy for Indos has recently become a subject of discus- sion. This especially concerns the position of the elderly among them (ibid.). The concern is to what extent the first generation of migrants among the Indos suffers from specific problems in that deterioration in the physical or mental condition of retired and ageing Indos generally leads to their dependence on Dutch institutional care. The question then arises as to what extent  H. N. EDELMAN ET AL. 27 they will still feel at home in these totally Dutch institutions. This discussion frames the research reported on here, which seeks to contribute to a better understanding of, and hence to the resolution of, this problem. The Social Environment of the Indo Community and Its Significance—Findings, Analysis and Disscussion The Social Network within the Indo Community The social network within the Indo community is one of the critical aspects of Indo life to understand how Indos live and pursue their leisure in the community. Community is understood here to be a place where people live and where most of their activities outside of work are concentrated. The social network within the community, however, becomes even more important during retirement, when people who have ceased working lose a large part of the social network based on their employment and workplace. The importance of the social network to retirees within the Indo community will, therefore, be analysed in this section through a consideration of a number of research ques- tions, which are related to the above issue. These include: 1) What role do Indo clubs play in t he community of retired Indos? 2) With what kinds of people do retired Indo mix, and who are their friends most often (i.e., Dutch, Indo or Indonesian)? These two research questions will be answered through the discussion in the following sections. Discussion The Role of Indo Clubs and Foundations There are many reasons for forming a club, but the main ones are to provide a forum for undertaking activities together, for sharing interests and experiences, for socialising and doing fun things together and for supporting each other when it is neces- sary. Of interest to this study, then, is to determine how impor- tant the role of Indo clubs is in the life and leisure of retired Indos? It is first necessary to compare the incidence of club mem- bership of the respondents at various stages in their lives. Thus, the respondents were asked whether they had joined any club during their y outh, as adults (i.e., while working) or during retire- ment. They were also asked what kinds of clubs they belonged to and their reasons for joining. The Table 1 below shows club membership and its continuity from youth through retirement. While the table does not indicate whether the membership of the respondents over time is in the same or different clubs, it does show that there is a decrease in overall club membership among the retired Indos who have at some point in their lives joined clubs. While 27 were club members as youths, only 20 are members in their retirement. Six out of the 27 respondents who joined clubs in their youth discontinued membership com- pletely when they became adults and have never rejoined clubs. Three of the m said that they did not ha ve much time when their Table 1. Club membership of responde nt s . Single Female Single Male Marr i ed Female Married MaleTotal Y A R Y A R Y A R Y A RYAR Yes 7 4 4 8 7 5 5 4 5 7 6 6272120 No 3 6 6 2 3 5 5 6 5 3 4 4131920 Y = Youth; A = Adult; R = Retiree. own kids were small, and that they really spent most of their time with family obligations and family-centred recreation. The others simply said that they do not like being tied to any group and having club obligations. A retired female who used to work as an administrative clerk at the Ministry of Health in The Hague responded when asked by the interviewer as follows: Interviewer: Were you a member of any club before retire- ment? Respondent: No. Interviewer: Please, can you tell me why not? Respondent: Yes, it is because I don’t like going to clubs and being told what to do, when to do it and under what circum- stances. I want to go wherever and whenever I like. Interviewer: Tell me then, how about now, are you a member of any club? Respondent: No, I am not at all. Interviewer: Why not? Respondent: To tell you the truth, I don’t need a club to do things. I have other activities that I like to do by myself or with my family and friends in my own time. You see, I don’t have time for a club. In addition, from the interviews, it became clear that 12 out of the 20 respondents who remain members of clubs have been club joiners throughout their lives. Most of the respondents who continue being club members do so because they enjoy the club activities and their corresponding social life. In addition, 4 of the 20 respondents who are club members in their retirement joined clubs in their youth, ceased to be active as adults and then joined again once they stopped working. They said that before retirement they were so busy with their work and family obligations that they did not have time for joining any clubs. Now that they are retired, however, they have plenty of time for doing whatever they want to do such as joining clubs to meet other people with the same interests, to socialise and so forth. On the other hand, several respondents (4 of the 27) who were active in clubs during their youth and adulthood were not in their retirement. These were members of athletic clubs where they played various sports when they were younger. Because of ageing and declining health, they became inactive as athletes and therefore gave up their club membership. They now do other things with friends and family in their own time. Two of the 20 retired club members did not join clubs during the youth or adulthood, but have joined since their retirement. One of the respondents said that after her husband passed away, she needed to have more activities to occupy her so that she does not stay at home and feel lonely all the time. The clubs are a place for her to meet people and do things. On the other hand, the other respondent was not a widow and joined a tennis club because she wanted to have a common activity to pursue with her husband. Of the 20 retired Indos who are club members, 13 are mem- bers of various Indo clubs, 8 belong to sport clubs and 6 are ac- tive in other kinds of hobby and interest clubs. Obviously the Indo and sports clubs are the two most popular. The reasons are apparent from the following grouping of their comments re- garding why they joined clubs: Most joined clubs so that they would meet other people for socialising, extending their friendship circle, meeting others with the same interests, talking about the old days (“Tempo Doeloe”), etc. (N = 16); Other respondents became members to keep fit, for health purposes, to participate in a sport, etc. (N = 8); and Some joined clubs because membership keeps them busy,  H. N. EDELMAN ET AL. 28 and it fills their time with positive activities such as helping other people or developing a hobby (N = 6). The respondents were also asked another, related question, What does the club mean to you? This question was asked as a check on how much club membership means to the 20 respon- dents who are active, and the answers can be grouped as fol- lows: The club is important and means a lot as a place to meet other people and socialise, to do things together with other members and to help other people (N = 9); and The club is not so important (N = 11), although it is a place to meet other people, socialise, do thing together with oth- ers and help people. The following exchange between a woman who is a former primary school teacher and the researcher represents an exam- ple of the first set of responses to this question. She expressed feelings towards club membership for both herself and her husband as a couple: Respondent: Our clubs mean a lot to us, because they are places for meeting people, making friends and helping other people who need assistance. Interviewer: What do you do at the clubs? Respondent: Well, my husband and I help in doing various things together with other club members. You know how it is among the Indos; we always eat ··· and eat ··· food, enjoy our- selves by talking to each other and of course meet other people. Interviewer: Do you have a commitment towards the clubs? If yes, please tell me what it is. Respondent: Yes, certainly. We donate some money for the clubs and for helping other people. For example, one of our clubs always gives some money and clothes to help poor people in Indonesia. I also write some articles and give talks on dif- ferent topics, including my own experiences. After analysing the respondents’ answers to the questions on club membership and the reasons for joining them, it becomes obvious that most of the retired Indos have joined Indo clubs in order to meet other people, socialise, do activities together and help others. Although only 9 have said that the club is an im- portant aspect in their life, all the respondents have said that their club is a place for them to meet other people, socialise, do activities together and help people. It is clear, then, that clubs have a significant role for a substantial segment of the retired Indo community with regard to social life and leisure activities. The Role of Family and Friends An important element of Indo culture, which is due to the heavy influence of Asian culture, is the very clear priority that the family has in life. In Eastern cultures, it is critical to soci- ety’s judgement of a family’s success in life to be able to show that the family bond is strong and that the children behave properly and have good manners. These are the main aspects to measure in order to assess whether a family is close and happy. Unlike with Europeans, however, there are two family cate- gories in an Indo family that need to be taken into consideration here. The first is the immediate family (i.e., what the research- ers call the inner bond), which consists of children, grandchild- dren, brothers and sisters. This is already a broader concept than what is considered the immediate family by Europeans (i.e., parents and their children). The rest of the family, that is, the extended family (i.e., the outer bond), is composed of the other relatives, but the kinship bond is also stronger here than with Europeans. It has a high value. Love, closeness, trust, loyalty, and respect are all bound up in these family ties. In this respect, the family values of the Indo family resemble those of the Indonesian family. A married, retired electrical technician, when discussing elements of Indo culture that remain part of his family life, said: Respondent: Well, one thing that is still part of our family is that the closeness and bond between family and friends is val- ued highly. Interviewer: How important are these things to you? Respondent: They are very important to me. When the respondents were asked what element of Indo cul- ture is still part of their family life, 23 out of 40 noted how im- portant family bonds are. This is the case even though most of the respondents have all their family and relatives in the Neth- erlands. In fact, 31 out of the 40 Indos interviewed in this study have their entire inner and outer bond relations living in the Netherlands, and only 9 have family or relatives in other parts of the world, including Indonesia. Of those interviewed, 30 said that they see both their inner and outer bond relations frequently, and only 10 responded that they do not see them as often a s th ey would like. The reasons given include distance, difficulty in travelling and so forth. Nevertheless, they said that they keep in touch, mostly by phoning each other. A married male, who retired as a civil servant, was asked whether his family and re- latives are all living in the Netherlands. He answered: Respondent: Most of them, but I still have some family in In- donesia. Interviewer: Do you see them (i.e., those in the Netherlands) frequently? Respondent: Not really. Interviewer: Please, could you tell me why not, and what do you mean by not really if you don’t mind? Respondent: We used to visit each other often when we were younger. Now we see each other periodically, but we are keep- ing in touch by phone. One of the reasons is the distance. Also, they are older than I am and not so healthy. Friendship is also important among retired Indos. Visiting friends and having leisure activities in common are an integral part of the respondents’ lives. Of the 40 respondents, 13 have said that visiting friends is part of their leisure and an important aspect of their social lives. As will be discussed further in Sec- tion 5, most of the respondents’ friends are Indo, and they have thus formed a social circle among the Indo retirees, which sets them apart from most Dutch elderly. In summation, family and friends play a significant role in the social life and leisure among the retired Indos of The Hague and its surroundings. Current Leisure Facilities The Indos are considered fully integrated into Dutch society by the Dutch government, although the data of this study, which are analysed in this chapter and the previous one, indicate that they are certainly not assimilated. When they came to the Neth- erlands, they were not considered as a separate group of com- mon immigrants or foreign refugees from the Dutch East Indies, but as “repatriates” or repatriaten in Dutch. That is, they were considered along with the white Dutch repatriates as citizens returning home. This concept of Indo repatriation explains why they have been treated differently from the post World War II immigrants to the Netherlands, who have come from Turkey, Morocco and other countries. The Indos came with knowledge of the Netherlands, which they acquired in school, and they spoke the Dutch language. In this sense, adaptation was easier for them. However there were many other aspects of repatriation and life in the Netherlands to adjust to. The Indos needed legal, financial, social and psychological support in a number of ways to get settled in their new (or old) homeland. Consequently, they  H. N. EDELMAN ET AL. 29 formed clubs, associations and foundations among themselves to provide mutual support for their relocation and integration into Dutch life. One of the widows interviewed in this research, who came to the Netherlands as a married woman with children and later retired as a teacher, when asked what she thought initially about her new country said: To tell you the truth, I was confused and worried at that time. We knew about the Netherlands from school, and we came here in the past for vacation. However, we were insecure about our future, so we were afraid to live here in the Netherlands. If we had had a choice, we would have preferred to live in Indonesia. You know, basically we were thrown away, so we had to leave. Another widow, who was a retired secretary, when asked how she had made contact with the local people and/or the Dutch to start a new life answered: It was hard in the beginning, because most of the Dutch did not have much information about people from the East Indies (Indonesia). They always asked us where we learned Dutch. You speak Dutch very well and clearly, they would say. I told them that I learned it on the boat on my way here. You know, this was because there was a lack of information and knowl- edge that we spoke Dutch in the East Indies and that we also had a Dutch educational system, Dutch groceries, etc. A married couple, the husband of which used to work as a government employee said: When we arrived here, we were put in a small room in a “pension”. We made a first contact with a Dutch social worker, who came over to tell us how to live in the Netherlands and wha t to do. The social worker told us, for example, that we we re onl y allowed to take a bath once a week, so we cleaned ourselves with a washcloth daily. It was very difficult to adjust to these conditions, when we were used to taking a bath at least twice a day and to changing cloth e s e v e r y day. Here all of a sudden, we had to wear clothes for a few days before changing to fresh ones. You can imagine how hard it was for all of us to adjust to this new life. Stichting Pelita The Pelita Foundation (Stichting Pelita in Dutch) was founded in 1947 on the initiative of repatriates to assist those fleeing the former Dutch East Indies to adjust to life in the Netherlands (van der Hoeven, 1996). The more than 265,000 repatrianten arrived in several waves (see Section 3.3.2.). Ini- tially, the foundation helped these refugees with the legal issues of their “repatriation”. The refugees, a large number of whom were Indos (especially in the 1950s and 1960s), were seeking a safe haven (Oei & Schreuder, 1996). In the beginning, as was suggested above, the key word for those arriving was adapta- tion: adaptation to Dutch society, adaptation to the Dutch cli- mate, adaptation to the Dutch way of living and adaptation to Dutch food. In this period, the foundation provided significant material help. With the passage of time, however, non-material help became much more important. Many repatriates were haunted by the wartime past and not entirely happy with the consequences of acculturation. Since the repatriates comprised a number of distinct groups, the Pelita Foundation developed programs of assistance for each of them. These groups included Indos, Totoks, ethnic Indonesians, Molukkens, ethnic Chinese Indonesians, children of Japanese and Korean fathers from the occupation, the spouses of repatriates and those Indonesians who had served in the Dutch army, i.e., the KNIL militairen (van der Hoeven & Diederen, 1997). In all, sixteen so-called client groups are differentiated by the foundation (van der Ho- even & Diederen, 1998). Of all these groups, however, the largest asking for assistance was the Indos (van der Hoeven & Diederen, 1997). These have also been subdivided for assistance by the foundation according to their dates of birth; that is, those born before 1924, those born between 1924 and 1938, those born between 1938 and 1945 and those born after 1945 (ibid.). For the purposes of this thesis, the first two groups are significant in that they are those who are now elderly or recently retired. The oldest among them have often suffered and still do from isolation, the feeling of being uprooted or homeless, fear of dying in a strange land, etc., all of which can lead to poor health. Moreover, the social ser- vices sector has rather incomplete knowledge of their specific historical, societal and cultural background (ibid.). In contrast, some of those born between 1924 and 1938 have suffered from difficulties at work or from unemployment and from achieving only partial integration into the Dutch way of life. They have also been plagued by poor relations with au- thority, social isolation, problems in relationships, physical and mental difficulties such as fear, depression and sleep distur- bances, as well as financial difficulties, etc. The Pelita Founda- tion has developed programmes to ease some of these difficult- ties for ageing and retired Indos, including developing materials for social workers who work with them and otherwise extend- ing to public authorities and private caregivers their expertise (van der Hoeven & Diederen, 1997 & 1998). The founda- tion now has in its employ 23 social workers spread throughout the Netherlands. Aside from giving advice of a legal or personal nature and directing individuals to places where they can get expert assis- tance or therapy, certain social activities are also organised by the Pelita Foundation, including those for elderly and retired Indos. Discussion groups are organised, as well as exhibitions, fairs, etc. With regard to leisure, perhaps the most important Pelita activity for this group is De Brug (The Bridge in English or Jembatan in Bahasa Indonesia), which extends the opportu- nity to meet other Indos, in someone’s home. This visiting of family and friends at their homes has previously been men- tioned (see Section 4.3.2. above; also see Sections 5.3.1. and 5.3.2.) as a major social activity of Indos, which they have car- ried over from Asia to Europe. Twice a month, social gather- ings are held to chat, eat and bridge the gap between the present and the past. Guest speakers are sometimes invited and creative activities organised by the volunteers (around 20) who operate this activity for the foundation. De Brug has been in operation for more than fifteen years. Much additional information on the De Brug activities was acquired in an interview with one of the Pelita social workers who co-ordinates the programmes of De Brug. This is summa- rised in the rest of this section. The Masuk Saja (Just Come In) project in Amsterdam, which was visited by the researcher, is one of the De Brug pro- grammes and is common in other cities as well, including The Hague. It is a sort of social club for retired Indos where they can come in and meet each other every fortnight. There is no formal membership, and it is a place, which is open to everybody. Any person can simply come in and join in the activities. This pro- gramme takes place in a community centre that is not subsidised by the government. Instead, it is partly financed by the income that is earned from the people participating in its various pro- grammes who purchase food and drink there. This helps cover operating costs such as gas, electricity, cleaning, etc. Another source of income for the centre is Pelita itself, which rents the building space specifically for the Masuk Saja project.  H. N. EDELMAN ET AL. 30 The centre building was formerly a Catholic churc h and foun- dation, although at present, it belongs to the municipality. The manager of the centre is a Dutch woman. The social worker was asked what the purpose of the centre is, and he replied: Respondent: The purpose of the centre is to put on program- mes and activities to attract old people to come and meet others like them and in so doing to get them out of their isolation. The idea is that they should not spend all their time alone at home. Thus, M asu k Saja is a ctua l ly a n at temp t to pr e ven t is ola t ion am ong the aged/elderly in the Indo community. Interviewer: What is the reason for locating the centre in this area? Respondent: Well, in the past there were a lot of families with children here, but when the children grew up and got jobs elsewhere, they moved to other places in the country. Thus, there remain a lot of old and single people in the area, many of whom are Indo, which is one of the reasons that the centre was founded in 1984. Another reason is that this church, reflecting a general trend in the Netherlands, experienced a decline in attendance after World War II, so that it became under-utilised. The local community has, therefore, tried to bring people to- gether in a form without any Christian religious content. Interviewer: What kinds of programmes have been organised, and for whom? Respondent: Several organised activities take place here, in- cluding, for example, drawing, clay crafts activities, various other crafts, as well as discussion groups on different themes. These groups also function as support groups for their members to talk about their problems. There is also a social group, which meets here twice a week and has a snack or a meal together, as well as a separate Indo social group. These programmes are mainly for old people. Interviewer: What are the opinions of the members and visi- tors about the programmes? Respondent: Their opinions about the programmes are gen- erally good, and the painting, drawing, and clay crafts active- ties are well attended. The Masuk Saja co-ordinator of the cen- tre, who was interviewed by the researcher, believes that it is not the activities themselves that are so attractive, but rather getting together with other retired Indos and gossiping that draws the Indo elderly to them. The Indos who come to the centre also organise a Pasar Jem- batan once a year to display the Indonesian culture to the Dutch and to other ethnic groups. This cultural event means a lot to the Indos in that they can express themselves through the pro- gramme. According to the co-ordinator, it seems they like the event and try to do their utmost to make it a successful event. There are other leisure activities, which have been organised at the centre within the framework of Masuk Saja. These in- clude gymnastics for exercise and visiting other Indo clubs (Ru- mah Saya). These activities are organised for a group, because people can be encouraged to participate and, whe n some people agree, others can be convinced to take part. The latter activity, however, doesn’t really attract the Indo club members that much, and they don’t like doing this kind of activity for too long according to their co-ordinator. When he was asked why, he answered: I think it is because they get bored visiting other clubs. It is a hassle to get to them, and they seem to value more highly get- ting together in a place they are used to. They also prefer being together in small groups with Indos they know and just chatting over food. Pasar Jembatan has been organised especially for the Indo people and other Dutch at the centre as part of the centre’s cul- tural programme. Whether intentionally or unintentionally, the centre has a role in preserving the Indo culture through this programme. The co-ordinator, when asked what the role of the centre is in preserving Indo culture and traditions said: The role of this club in preserving Indo culture and tradition is very important, because there are several clubs in Amsterdam, and each has its own character. For example, one club is for dancing, and another is for bingo. Here, in the Masuk Saja pro- gramme there is no bingo or dancing. It is a place to socialise and talk about old times in Indonesia. However, with good food, programmes and speakers, it attracts the attention of the area’s residents. There is also another service, which this Masuk Saja project provides to the Indo people. That is, Pelita social workers are available at specified times with whom they can talk or discuss a particular problem in an informal atmosphere. A special pro- gramme for Indos takes place on Tuesday afternoon every fort- night, where they can meet, eat and talk. Thus, after meeting other people, chatting and eating for a while, they can turn to a social worker for some advice. If the problem is really serious, the social worker can schedule an appointment for a detailed discussion. People who come and attend the programmes here are mostly over 65 years old with a pension averaging approximately NFL 1600 to NFL 1800 (approximately US $800 to $900) net per month. It should be noted that there are not very many Indone- sian people who come to the programmes, and those who do, come very seldom. About 80% of the people who attend are Indo. Thus, a very high percentage of Indos compared to Dutch in the community participate in the activities. This is, of course, due to the fact that the programmes are mainly for Indos, and the Dutch who come do so to act as volunteers to serve food and drink, etc. Married couples use the club more than single Indos, because they are those who earlier came to the church with their fami- lies, partly to socialise, so it remains a comfortable place for them just to just that. The club is not used as a place for lonely retired singles to find new partners. It seems there is an unspo- ken feeling among retired or elderly Indos that if single women (or the fewer single men) would go to the club, it would be considered a threat to the couples. Furthermore, when the co-ordinator was asked if meals are served at the centre, he explained: Respondent: Yes, meals are served in the centre’s canteen, which is a very attractive feature, especially for some of the aged who are unable to cook. Eating is the central focus of activity, not only because of the food itself, but also because of its social function. Thus, having a canteen in the centre is very important, because of the central role food plays in Indo cul- ture. Interviewer: What kinds of food are served the most? Why is that the case? Respondent: Well, the food served here is Indo or Indonesian food, because Indos, of course, expect only to eat Indonesian food. Interviewer: How much does the average meal cost per per- son? Can the people afford to pay for the activities and meals? Respondent: Oh yes, most of the visitors can afford both the food and activities here easily. Meals cost on average NFL 10 (US $5), and most of the activities are not expensive either. The purpose of the programme is to attract people to partic i p at e. Interviewer: What attracts new visitors to the centre and its activities? Respondent: I think new visitors come to the centre because  H. N. EDELMAN ET AL. 31 of the friendly and informal atmosphere of the centre itself. The retired Indos talk to each other about the old times in Indonesia (i.e., Tempo Doeloe), and they are interested in the guest speak- ers who come to talk about health, Indonesian culture, and also to relate stories about Tempo Doeloe, which they like a lot. Stichting Tong Tong In contrast to the various activities of the Pelita Foundation, the Stichting Tong Tong (Tong Tong Foundation) has as its pri- mary activity the organisation of a large Indonesian fair every year, that i s, the Pasar Malam Besar (The Big Fair) in The Hague. This two-week event has become a Dutch institution and is wi- dely attended (average annual attendance exceeds 135,000) by all elements of Dutch society. It ranks number four nationally, in terms of attendance, behind only the annual household, auto and vacation fairs. In addition, all Indo people residing in the country know it as an important cultural resource. The basic objective of the foundation is to preserve Indo culture and to make known the culture itself to other people through the Pasar Malam Besar. In consideration of the importance of this spe- cific event and of the foundation in general, the researcher in- terviewed the Director of the Pasar Malam Besar, who is also a Board member of the Tong Tong Foundation. The rest of this section reflects the information acquired in that meeting. When the foundation was formed forty years ago by Tjalie Robinson, all of those involved had come from Indonesia and shared a common Indo background, the culture of which they all knew about from their own direct experience. However, with the passage of time, the Indos have had children born in Holland, who only know Indo culture second-hand from their parents. The whole idea of the Dutch East Indies is not real to them. Thus, these young people and succeeding generations of Indos need to be educated about Indo culture. For them, the Pasar Malam Besar is an opportunity to be informed about their background, so there are programmes about the history and culture of the Netherlands East Indies especially aimed at them. When the Director of Pasar Malam Besar was asked what the purpose of the foundation is, she said: Well, we formed the foundation and created the event with the idea of conserving, stimulating and propagating Eurasian/ Indo culture in general. Lately, though, the programme has been more focused on education about the Indo history and culture for the younger generations of Indos. The fair itself is a major event of the cultural and entertain- ment calendar of The Hague. It takes place in an enormous complex of tents across from the central train station in the city. There are five theatres inside this complex, so there are five different performances taking place on separate stages simulta- neously. These shows offer choices to visitors ranging from presentations with educational content to cultural events to lei- sure activities of pure entertainment. When questioned about the kinds of programmes that have been organised and for whom the Director of the event explained: Well, there are many varieties of activities and programmes during a two-week event. There are five theatres inside the tent with different kinds of programmes for various purposes. For example, there are informative and intellectual discussions about different themes related to various issues of Indo culture, his- tory and about the Indo people in the Netherlands. They are or- ganised and conducted by various institutions and guest speak- ers. We organise other leisure activities of pure entertainment as well. For instance, there are Indo singers, bands and kront- jong musical groups from Holland that perform in the Pasar Malam Besar each year. In addition, krontjong orchestras from Indonesia are invited. For example, in 1998, a krontjong group from Toegoe took part. They are from the area of Indonesia where Krontjong Asli, the original krontjong music, is still being played. The foundation also invites each year groups from the different provinces of Indonesia to present their traditional music, dance, theatre and cultural performances. This year East Java was highlighted, and the music and dances from the area were given special attention. Nevertheless, if there is no kront- jong in a Pasar Malam Besar, the older Indo visitors will be disappointed. It should be noted, however, that there are other types of mu- sic, which are very popular among Indos, such as music from Hawaii, Caribbean, and the Antilles, country and western music, as well as rhythm and blues, and they are also showcased at the Pasar Malam Besar. Aside from music and dance, there are of course other programmes with different intellectual themes. The organisers are trying to find new groups and different pro- grammes all the time, which Indos will want to see and enjoy. The interviewer asked the director of Pasar Malam Besar what the opinions of the visitors about the organised programmes are, and she said: The opinions of the visitors about the programmes are very positive. The organisers conduct a survey every year after the event, and the results have shown that, on average, visitors rate the event 8 on a 10-point scale, which is rather good. Nevertheless, the researcher learned in this interview that there are several obstacles faced by the foundation. The primary one is financial. In order to educate people, it is necessary to continue to put on the fair, as well as to publish books and other written materials. This requires money. While the Tong Tong Foundation would like to publish books on different subjects each year, for instance, a lack of base finance forces it to look for sponsors who will give grant support to projects on a case by case basis. It is very difficult to get such money, so this is the first obstacle. A second major obstacle is that most Dutch people know very little about the history of the Dutch East Indies, and this is reflected in the difficulty of obtaining funding. For instance, it is very difficult to explain to such potential sponsors what the purposes of the Tong Tong Foundation are. If one would say to them that one is an Indo or Indo-European, then they would be likely to say something along the lines of, “Oh you are Indone- sian”. If one then says no, that an Indonesian is different from an Indo, then they are likely to reply, “Oh, why don’t you want to be called an Indonesian?” The answer is, of course, that Indos are not Indonesians. Most Dutch, then, have an inaccurate conception of the Indo people and of Indonesian s. They still look upon Indos as though they are a separate group of people who own a private ship called the Pasar Malam Besar, which is only for the Indos. The fact is that 40% of the visitors are not Indos Nevertheless, the role of the foundation in preserving Indo culture and traditions is very important in comparison to other Indo organisations. The foundation has done more than any other Indo institution in preserving the culture of the Indos. As long as there is still money, the foundation can continue to pre- serve the Indo culture. One way it attempts to do this is by increasing the number of the visitors to the Pasar Malam Besar by publishing 3 times a year the Pasar Krant (Market Newspaper) and distributing it throughout the Netherlands for free. Since this newspaper has been issued, there has been an increase in the number of visitors. The Fair is also advertised in magazines, newspapers and wher- ever it can receive attention, and word of mouth plays a large role. When the Director was asked how long the Indo culture  H. N. EDELMAN ET AL. 32 will last in the Netherlands, her response was: This is a question that every Indo in the Netherlands should think about. When the foundation staged the first Pasar Malam Besar, there were people who were pessimistic about the inter- est of the Indos in their culture. They reasoned that the older generation of repatrianten will die out, and then it will all be gone. In stark contrast, however, the number of visitors contin- ues to increase, younger generations remain interested in the event. It is very difficult to predict how long this interest will last and in what form it will be manifested, but as long as the Indo people remain interested in their roots, it will last. There is a chance that this event will go on for generations, and why not? The Indos are already in the Netherlands for three gen- erations, and they are still coming to the Pasar Malam Besar. Other Indo Clubs and Organisations There are many other Indo clubs, foundations and organisa- tions in The Hague and its surroundings, which provide differ- ent kinds of activities for their members. Their activities are supported by membership fees and fund-raising from the activi- ties. The existence of the clubs depends on the members. A few examples are OVTV—Ontspannings Vereniging Tropen Vrien- den or Stressless Organisation of Friends from the Tropics, Nazaten Indische Nederlanders en Sympathisanten (NINES), Stichting Indisch Cultureel Centrum (ICC), Serukun, Bunga Ma- yang. While these and others may have been founded for spe- cific purposes, most Indo clubs have at their core the basic so- cial function that is so critical to the Indos. As has been made apparent throughout the preceding sections of this chapter, so- cialising with friends over a good Indo meal is an extraordinar- ily important part of the Indo value system. The Indo social clubs also provide other kinds of program- mes for their members. Some, such as OVTV, NINES and ICC, organise various cultural events and sport activities, including those for badminton, tennis, etc., travel together to places. The types of cultural events attended normally have some connec- tion to Indo culture and Indonesia as the birthplace of most re- tired and elderly Indo people. The clubs also organise activities, which interest their members. Thus, they organise Indonesian traditional dance performances, Indonesian language courses, Indonesian traditional Angklung music performances (i.e., mu- sicians playing bamboo musical instruments with long rods that are swung back and forth to create melodies and rhythms), Indo and Indonesian traditional fashion shows, Indo and Indonesian cooking classe s and so fort h. The role of clubs, or ganisations and foundations is important for the Indo community in providing them a place to meet other Indos, to participate in activities to- gether, and, to a certain extent, to help in preserving the Indo culture, traditions and manners. In a detailed interview, the Chairman of OVTV was asked several questions regarding the kinds of the club activities or programmes that have been organised for members. He com- mented as follows: Basically, we organise programmes at which people can en- joy other the company of others meet more people and have a good time. Based on this, we organise six dance parties a year, a small event called “Soos Avond” (Evening Club), a bridge club once a week, bowling on the third Friday of every month, a tennis championship once a year, as well as group travel to other European countries and some places in the Netherlands. However, we try hardest to keep our social bonds strong through our main event, which is called “Mid Wijk”. We go to a good hotel in Holland once a year. This year (1998), it will be held at “Present Palace” in Amello. The main idea of this activity is to bring all our members together. I think it is nice for the mem- bers to have such a holiday together, particularly for the single ones who feel they can not go to some place s because they don’t have partners. For the Mid Wijk, this is not a problem since they can go with all their friends in the club. Besides these ac- tivities, the club also organises different cultural events that are mostly related to Indonesian and Indo culture as part of our big evenings for different occasions. One of our purposes is pro- vide Indonesian and Indo culture for our members who are mostly Indos coming from the East Indies. They comprise about 90% of our club membership. They really liked and responded well to cultural events. These are, naturally, not the only leisure opportunities for Indos in their communities. There are many other leisure facili- ties available to Indos, in general, and the respondents of this study, in particular. However, these are the same swimming pools, community centres, libraries, etc. used by the local peo- ple in general. Actually, there are not many special leisure fa- cilities or Indo clubs only for Indos in The Hague and its sur- roundings, which are connected to the local community. The Indo people are considered to be fully integrated into Dutch society, and local government, therefore, does not feel any need to pay any attention to the issue of whether it is necessary to support retired Indos, who feel more comfortable doing things with other Indos in their leisure time. It is necessary, then, for those retired Indos who want to meet and be with other Indos to make individual efforts to find and join a club, which suits their leisure needs, and where they feel comfortable according to their norms and culture, or to form small social groups among their friends and families. Integration into Dutch Society Beyond considering the social network within the Indo com- munity, integration into Dutch society is also an important ele- ment in the consideration of Indo leisure. It is, therefore, nec- essary to look at the relevant research questions, which can help in providing a basis for the discussion of this matter in the fol- lowing sections. These inc l u de: 1) To what extent do the Indos themselves try to maintain their unique Indo culture? 2) What elements of Indonesian culture do the Indos find it important to maintain in their old age in the Netherlands? 3) What do the retired Indos do to retain the Indonesian as- pects of their culture? 4) What elements of Dutch culture do the Indos feel uncom- fortable with in their old age? 5) How close do these Indo people now feel to Indonesia? These research questions will be answered in sequence through the discussion of the following sections. The Importance of Self Identity Self-identity is an important aspect of social life. As a social being, each individual needs to identify oneself in terms of cer- tain social traits and values belonging to a particular social group. The study population in this thesis considers itself as Indo with regard to its physical and social characteristics. They come from the same background and/or place, and they are characterised by mixed blood and a mixed culture of the East and West. The way in which the Indos in this st udy identify themselves is sum- marised in Table 2 below. While half of those interviewed for this study (20 of 40) con- sider themselves completely Indo, a large number of the respon- dents (18 of 40) have identified themselves as both Indo and  H. N. EDELMAN ET AL. 33 Table 2. How respondents identify themselves. Single Female Single Male Married Female Married Male Total Dutch 0 0 1 0 1 Indo 3 5 5 7 20 Both 6 5 4 3 18 International 1 0 0 0 1 Total 10 10 10 10 40 Dutch. It is clear here that they are not pure Dutch or Indone- sian in their own eyes, and they also don’t simply feel Indo-Eu- ropean but rather specifically Indo-European Dutch. Naturally they have different traditions, values, norms and culture than the pure Dutch or Indonesian, but what precisely is Indo culture according to them? Table 3 below illustrates this. The respondents are split basically into two groups. In the first, 16 out of 40 respondents feel that their culture is more Eastern or Asian in its characteristic values. These respondents were born in Indonesia and have strong feelings of connection to their birthplace. They have been brought up in more of an Eastern way of doing thing s, so they feel more comfortable con- sidering themselves as such, rather than as Dutchmen with di- rect and unseemly Western manners. They also feel that the Indo culture is completely different than that of the Dutch. They feel their own way of life is Asian or Eastern. They are hospitable, warm towards others and consider themselves easy going in their social attitude. For example, it is not necessary for a visi- tor to make appointment to come to their homes. One just visits, and if they are not home, it is too bad. However, if they are at home, unannounced visitors are always welcome. It is very dif- ferent attitude from that of the Dutch, who expect one to make an appointment first rather than disturb one’s plans or privacy. Thus, when one of the married respondents, who retired as a government employee, was asked what he understands Indo culture to be said: Indo culture to me means hospitality and “gotong royong” (i.e., helping each other spontane ously ). Eating together is a part of this because we like eating so much. Extending friendliness and openness to other people is also important. For example you can not just go to a Dutch home without an appointment, but you can do this with an Indo family. Another, similar view from the first group is that of a wid- ower who is a retired construction company engineer. He said: Well, it is difficult to say exactly what Indo culture is, how- ever it is better for me to describe it. We as Indos have different a way of life. I mean, Indos are completely different than the real Dutch. The Indos are more easy going in many ways, for in- stance, it is not necessary to make an appointment to visit a friend. You just come and if they are not at home is a bad luck. If they are there, you are always welcome and share what they have at home with you. It is quite different when you compare to the Dutch way. Members of the second group, however, i.e., 17 respondents out of 40, feel that their Indo culture is actually a mixed culture of the European and Asian. According to them, Indos are mixed blood, so their culture is also mixed. That is to say that the Indo culture reflects the origin of the people. One of the married res- pondents who retired as a secretary explained: I have two cultures, that is, one from Indonesia and the other Table 3. How respondents charac terise Indo culture. Single Female Single Male Married Female Married Male Total Euro/Western 0 0 1 0 1 Asian/Eastern 4 3 5 4 16 Mixed 4 4 4 5 17 from the Netherlands, and I, as well as other Indos, have the opportunity to take the best of both. This view was echoed by a married woman, who retired as primary teacher, when she said that: Being Indo means you have mixed blood from different kinds of people in the world, so our culture is also just like our blood. To me Indo culture is a mixture of different cultures, which are predominantly both Eastern and Western. Nevertheless, there were 7 respondents who felt that they don’t have any culture of their own; that is, they felt there is no unique Indo culture. One of the single male respondents, a re- tired graphic designer, was of the opinion that: There is no Indo culture. As an Indo either you choose Indo- nesian or Dutch culture, so being Indo, you have to ma ke a choice. Whether you take the culture of your father or your mother de- pends on the individual. A similar, if slightly more controversially formulated, re- sponse was given by a retired single male, who was formerly an administrative clerk in an insurance company. He said: There is no Indo culture. I think Indo culture is actually In- donesian culture, which was brought with and adopted by us. I mean Indos who live here. I think there is no such thing as an Indo culture, I just don’t believe in it. You know, some Indo persons will kill me for saying this, if they hear it. Living as a Subculture in the Netherlands The respondents a re Indos, and at t he same time they are Dutch. Being Indo and living in the Netherlands, they are not comple- tely comfortable when their Indo norms and values come into conflict with Dut ch ones. Indos have their own tra ditions, norms, habits, and culture, which are quite different than the Dutch. Although most of the retired Indos in this study are integrated into Dutch society and have to accept the norms of the society around them, they are by no means assimilated, so the respon- dents retain their own traditions, habits, norms and values, which are not fully European or Asian. These unique elements have become part of an identifiable Indo subc ulture. While living in the Netherlands as Dutch citizens and integrating themselves into Dutch society, they have nonetheless retained the elements of their separateness in Indonesia and further developed a cul- ture for themselves in the Netherlands. For example, there is a Dutch Indo vocabulary, an Indo way of expressing and speak- i ng, Indo food, whic h is neither Indone sian nor Dutch, Indo cloth- ing, and so forth. The Indo traditions, habits, norms and values will be discussed further in Section 3.3.4. Here, though, it is useful to show that as Indos, they will al- ways see their country differently than their ethnic Dutch both- ers and sisters. The respondents have been asked what they like least about the place in the Netherlands where they are living at the present time. The responses to this question determine what they like least about their immediate environment. Of the 40 respondents, 17 mentioned that, seen from a social perspective, they don’t like the rough attitude and impolite manners of the  H. N. EDELMAN ET AL. 34 Dutch (the Indo term is kasar). In addition, 14 respondents have indicated that they don’t like the weather. There are 6 who cite the increase of youth crime and vandalism nowadays, and one who dislikes Dutch politics. The other 2 respondents didn’t have any opinion. The following exchange is a good illustration of how an Indo feels being in the Netherlands and of how spending one’s child- hood in the Dutch East Indies can influence an Indo person’s sense of belonging. The respondent retired as a graphic designer and now writes books about different subjects related to his Asian birthplace He came to the Netherlands in 1937, when his father completed a job assignment in the East Indies. He was 11 years old when he arrived in The Hague. The respondent was asked what was his favourite place/city during his youth, and he replied: Respondent: Well, I spent part of my youth in Sukabumi, East Indies and part in The Hague. However, I must say The Hague was my favourite city, and it remains so even until now. Interviewer: Why is that? Respondent: Because it is near the sea. You know, I love wa- ter, and The Hague is a city of Indo pe ople. Its nickname is “the widow of Indonesia”. Interviewer: Wha t do yo u l ik e most about the Netherlands? Respondent: It is sad to say, but I don’t now and never have felt at home in the Netherl ands. However social security is good here. Interviewer: Could you tell me then, what do you like least? Respo nde nt: I must say the Dutch are rude (kasar) and impolite. Being Dutch citizens, but having nevertheless different val- ues in reacting to and observing the environment where they live is quite significant in determining what elements of Dutch cul- ture and values that the retired Indo respondents feel uncom- fortable with during their old age. Listed below are the social attitudes and values of the Dutch people that have been seen by the respondents as norms and values that contradict Indo norms, and which make them feel uncomfortable when they are con- fronted with them. Those statements of the respondent s that have similar meanings have been grouped together and each respon- dent has given several uncomfortable aspects, which they feel uneasy. Thus what has been found offensive include: The attitudes that reflect rudeness, roughness, impoliteness, aggressiveness and unfriendliness (N = 30); The attitudes which indicate excessive care in spending money (N = 3); and The attitudes that show formality and stiffness in making new acquaintances which give an impression that someone is keeping their distance from you (N = 5). These attitudes make the respondents feel uneasy at times in the communities in which they live. Sometimes the Dutch cha- racteristic of directness in reacting to a question or social situa- tion can make Indos, even after many years in the Netherlands, feel that Dutch individuals are unfriendly. One of the male res- pondents, a former technical officer at one of the Delta Works Projects was asked what element or part of Dutch culture he feels uncomfortable with. He has pointed out what he feels to be an explanation here. He mentioned that: The Dutch are very rational, but without emotion. On the other hand as an Indo, I feel that I am also rational, but at the same time, what I do and how is coloured by my emotions. A married couple has another explanation regarding the un- friendliness among the neighbours where they live. They feel the Dutch are quite individualistic, and this results in unfriend- liness. To quote, they noted: You know, we have been living here for a long time, but we don’t even know the neighbours who live around us. They say good morning and hello, and that’s about it. This distant atti- tude makes us feel uncomfortable and forces us to find other Indo people to make the acquaintance of. Despite all this, the retired Indos in this study are quite inte- grated into Dutch society. However, they still consider them- selves as Indos who feel more comfortable a ssoci ating with other Indo people who can understand and recognise their feelings, values, habits, traditions, and so forth. Moreover, the respon- dents are retired now and have more time for their leisure. As the results fro m the interviews re garding clubs show, which have been discussed above, most of the respondents who have joined the clubs belong to Indo clubs or organisations. It is very natu- ral that the respondents feel more comfortable a mong other I ndos in sharing their leisure activities. The Netherlands as Motherland The Netherlands is where the respondents in this study now live. Except for one lady, they have been living in the Nether- lands longer than they lived in Indonesia. However, even this person has lived 40 years in the Netherlands. She is 83 and therefore lived 43 years in the East Indies! The respondents have, nevertheless, been asked whether, if they had the oppor- tunity, they would go back to Indonesia and live there. Of the 40 respondents, 28 clearly stated that they wouldn’t live in Indonesia any more. They gave several reasons, and they can be grouped as follows: They like living in the Netherlands, and they are settled and used to the Dutch way of life after so many years of living in the country. They don’t know if they can fit in any more and adjust themselves into the present way life in Indonesia (N = 26); Their families and friends are here in the Netherlands (N = 10); and They had bad experiences during the revolution and still feel threatened (N = 1). On the other hand, 9 of the respondents said that they would go back and live there if they had the opportunity. These inter- viewees gave as reasons that some of their roots are in Indone- sia, and they love the Indonesian way of life. However, two of the respondents also mentioned that one factor could stop them from going. They were referring to their grandchildren. A typi- cal attitude is reflected in the response of a married couple. When they were asked whether they would go back to Indone- sia to live if they had the opportunity, they replied: If we had the opportunity, yes, no doubt we would go and live there. I (the husband) have had this thought before. I mean, when I was younger, I thought that if I were retired, I would live in Indonesia. It turns out differently now. After having grand- children, I tried several times to go to Indonesia for 4 to 5 weeks. I missed them, and it was painful. I don’t think I could really live so far away from them. There were also 3 respondents who would like to live in both countries if they had the opport unity. It is very difficult for them to choose to leave the Netherlands because of family, friends and the lives that they have built after many years living in the country. Ideally, however, they would love to be able to live six months in the Netherlands and another six months in warm and sunny Indonesia. For example, a widow who is a retired secre- tary said: If I could live in Indonesia, I would miss my family and friends. However, if there was the possibility that I could live in both countries—for example, if I could live in Indonesia for 6 months and live here for the other half of the year. Then it would  H. N. EDELMAN ET AL. 35 be an ideal situation. I would live in the two countries, which I love most. You know, I didn’t think I could make a choice if I had to choose. I won’t say that I wouldn’t like to live in Indone- sia, because I love the country and people. The Importance of the Indo Culture for Future Generations As has been discussed in a previous section, the Indo culture according to the respondents in this study is a mixed European and Asian one. Nevertheless, each individual has a different strength of feeling with regard to whether he or she feels more attraction to the Asian way of life or the European. It depends more or less on one’s upbringing, and on how much one has been exposed by his or her parents to both cultures. How close, then, do the retired Indos in this study feel to Indonesia now? The following Table 4 indicates this. It is very significant that the overwhelming majority of re- spondents (36 of 40) still feel close to Indonesia even after all the years of living in the Netherlands. What factors influence the feeling of the retired Indos toward their birthplace? Why do they feel this way? These two questions will be analysed in the discussion, which follows, in order to see what Indo cultural ele- ments the retired Indos themselves find important to maintain in their family lives in the Netherlands and pass on to future generations. The Norms and Values of Indo Traditions To understand fully the Indo subculture in the Netherlands, it is important to determine which Indo habits and values brought from the East Indies, which distinguish Indos from the ethnic Dutch, are still part of the Indo way of life in Europe. Main- taining these values and habits is as important to being Indo as being of mixed race. The respondents don’t feel comfortable without them in their daily life, and they include: Using water to clean oneself after using the toilet; Eating Indo food several times a week; Having close family bonds and getting together with rela- tives and friends; Having good manners according to Indo values and norms. This includes such elements as hospitality politeness, pa- tience, kindness, friendliness, warm feelings towards each other, helping others, respect for the elderly and older per- sons in general; Maintaining the use of the Indo language (Petjok has the old Malays base vocabulary), which was used when living in the East Indies prior to repatriation; and Having Indonesian objects around the house. This list was compiled from the answers of all respondents when they were asked what things or parts of Indo culture are still part of their family life. A married couple gave an interest- ing response. The husband was a retired employee of the Min- istry of Education, and the wife had devoted herself to being the homemaker for the family. They replied: Table 4. How close the respondents feel to Indonesia. Single Female Single Male Married Female Married Male Total Very Close 1 4 4 3 12 Close 6 4 4 5 19 Fairly Close 2 0 2 1 5 Not Close 1 2 0 1 4 Total 10 10 10 10 40 Respondents: Well, the elements of Indo values which our family still practice are Indo manners which we consider as politeness (halus) towards other people. Hospitality and open-door traits, which mean everybody is welcome, are some of our fam- ily traits. Our children like to speak some Indonesian words. It is actually “petjok”. Oh, another one that is equal ly important is Indo or Indonesian food, if you want to consider it. It is still part of our main food. We eat Indo/Indonesian fo od five times a week, and we eat potatoes and other normal Dutch food twice a week. Interviewer: How important are these things to you? Respondents: Oh, they are very important. All respondents were also asked to comment on the impor- tance of Indo cultural elements to them individually. Their re- sponses indicate their overwhelming closeness to things and va- lues Indo. Table 5 below summarises and groups their answers: The Importance of Maintaining Indo Culture, Traditions and Norms Given these answers about the importance of various aspects of Indonesian culture, traditions, norms and values in their lives, the researcher then sought to find out if they actually still prac- tised them. Thus, the question was posed as to, What elements or parts of Indonesian culture do you still maintain or keep? The answers can be grouped into several categories as follows: Personal habits: Included here are eating Indo food, eating in the Indo manner (i.e., with a fork and spoon or with the hand), and other Indonesian habits such a s using water (botol tjebok) to clean oneself after using the restroom, taking a ba th with a scoop for po uring the water over the body (mandi pakai/pake ganjung) and using a long pillow, the so-called Dutch-wife or guling (36 positive responses out of 40); Manners: This comprises kindness, politeness, patience, re- spect of an elderly or elder person, warm and friendly feel- ing towards others, helping each other, etc. (N = 21); Hospitality: Here are included being a good host and wel- coming guests (N = 35); and Culture: This covers language and music (N = 10). The following is a response to the above given by a married man, who retired as a government employee. He declared: Respondent: I still maintain the way of living that I got from my parents. I still use “botol tjebok”, eat Indo or Indonesian food every day, have polite manners according to Indo values (“ha- lus”) such as hospitality and so forth. Interviewer: How important these elements to you? Respondent: They are very important to me, and the most important thing is that my feelings won’t deny it. This comes from inside me. From these responses, it appears that the Indo retirees of The Hague and its surroundings still strongly practise many ele- ments of Indo culture. However, an important indicative factor in the practise of any culture is the consumption of meals re- flecting the typical cuisine of the country from which a group of people originates. To separate this from the categories dis- cussed above, the researcher looked at how often the respon- dents, all of whom were born in what is now Indonesia, eat Table 5. The importance of Indo values and habits to the respondents. Single Female Single Male Married Female Married Male Total Very Important 8 8 7 7 30 Important 2 2 3 3 10 Not So Important 0 0 0 0 0 Total 10 10 10 10 40  H. N. EDELMAN ET AL. 36 Indonesian food in a week. Table 6 below presents the results: It is obvious from this set of responses that the Indo retirees of the study population remain strongly attached to at least this element of the Indo culture. They will clearly miss the food if they are not able to eat it for a while. Accepting the importance of Indo culture to the respondents, along with the fact that their lives are imbued with the tradi- tions and habits of that culture, the salient factor in wanting to maintain the Indo culture, along with its norms and values, for future generations is tied to the compelling feelings that the respondents have towards Indonesia itself. Consequently, the question was asked, Do you still consider yourself part of In- donesia? Of the 40 respondents, 30 said yes, 9 said no, and 1 said sometime s. The following are some sample comments from several respondents. A widow who retired as a secretary said: Respondent: Yes , definitely I am still part of Indonesia. Interviewer: In what way? Respondent: I still keep the language, food and I practise an Indo way of life, which is close to an Indonesian one. A single male who used to work as administrative clerk an- swered: Yes, I do, because I was born there and also my parents and grandparents were born there. It is like “Tanah tumpah dara- hku” for me too. In every way, I feel an attachment that I can’t describe—just like a blood tie, which you can’t see. To me, it is important, and I feel strongly about it. Until the day I die, I wi ll feel that way. Here as well are the responses of the couple of which the husband is a retired technical officer from the Delta Works Project and the partner previously worked as an administrative clerk at one of ministries. He said: No, I am not part of Indonesia, because I am not oriented to Indonesia. Yes, my youth was spent there, but not all of my life. However, I like the Indonesian people and country, because I was born there. She answered: No, because I feel that now I belong here. I have lived in the Netherlands longer than in Indonesia, but I feel special for Indonesia only because it is my birthplace. However, I keep up my interest in Indonesia by reading and watching TV shows about Indonesia. The respondents have given a number of reasons for their responses. Of the 30 who answered positively, 20 said that they responded yes because they practise Indo customs in their daily life, which they feel is based on the Indonesian way of life. Another 10 answered yes because they consider that their roots are in Indonesia, and that this is a part of them that they can not deny and is always deep in their hearts. Those 9 that answered no did so because they feel they have been living in the Neth- erlands too long and don’t have any connection any more with the country. Finally, one person answered that he sometimes feels Indonesian and sometimes not. When this respondent is reminded specifically of Indonesia by something around him, he feels Indonesian. Otherwise, in his normal life in the Neth- erlands, he feels Dutch and doesn’t think of Indonesia. To confirm this overwhelming connection to Indonesia, the direct question was posed, Do you miss Indonesia? Of the 40 respondents 32 answered y es and only 8 no. The researcher then asked what specifically was missed, and the next Table 7 sum- marises these answers: Most of the respondents who miss Indonesia seem to miss most the Indonesian way of life and the country’s people. One married female respondent expressed her feelings in the fol- lowing way: Table 6. Frequency of Indonesian meals per week. Single Female Single Male Married Female Married Male Total Every Day 4 4 8 8 24 3 - 4 x/Week 4 4 2 2 12 2 x/Week 2 2 0 0 4 Once a Week 0 0 0 0 0 Never 0 0 0 0 0 Total 10 10 10 10 40 Table 7. Aspects of Indonesia missed by t he re s p on d ents. Single Female Single Male Married Female Married Male Total The People 3 5 5 8 21 The Country 3 2 0 3 8 Nature 2 1 0 2 5 Climate 3 5 5 6 19 Way of Life 5 6 5 8 24 Note: Respondents were allowed to give more than one answer. Hence the total number of response s i s more than the number of respondents. Now I am getting older, and I don’t know why, but I am longing for Indonesia more. Perhaps I am longing for my roots. A married male respondent replied: When I am in Indonesia, I feel that I am human, and I feel like being among them. Another married male noted: I often dream about Indonesia in my sleep. Given the importance of Indo values and habits to the re- spondents, the question arises as to how these can be maintained for future generations. An obvious follow up question, then, has been asked; that is, How did/do you keep your Indo culture for your children or family? These are some responses of the inter- viewees. First, a couple who have retired as a controller for social insurance and as a secretary said: We try our best to let them see how we live and where we com e fr o m, and we talk about it. We hope that they will take some good things from us. Well, basically, we try to be examples, such as when we practise a hospitab le attitude towards our kids. A widow, who is a retired secretary, said: Well, I taught my children about the Indonesian “adat” (way of life), which is part of Indo culture. I talked about Indonesia a lot. As you can see, I still speak the language and even speak “Sundanese”. In addition, a widower who used to work as an administra- tive clerk at the Ministry of Justice answered: I keep my Indo culture for my children and family by giving them the same upbringing that I got from my parents, especially from my mother. My grandma was Indonesian and she taught me her way of life, including good manners, hospitality and how to be polite. Finally, a married couple who worked as an exploration ge- ologist and a typist replied: You know, we try to keep our children attached to Indo cul- ture by eating Indonesian/Indo food at home. We eat Indone- sian/Indo food six times a week and Dutch food once a week. We also try to show them Asian hospitality and re spect for older people.  H. N. EDELMAN ET AL. 37 These and the rest of the responses that were given were gath- ered and grouped together to suggest the different appro a ch e s t ha t have been chosen by respondents. These are: Through family education by practising the culture, norms, traditions, values directly or indirectly at home (N = 21); By talking about one’s background and experience in Indo- nesia and reminding the children that they are of mixed blood (N = 9); Choosing not to practise Indo culture or tradition and letting the children choose what they feel comfortable with (N = 3); and Practising Indo values, tradition, and culture closely or to some extent, although there are no children to pass them on to (N = 7). Thus, the most common way of maintaining the Indo culture among the respondents’ families is by practising the culture, norms, values and traditions directly and indirectly at home through family education. Some of the ways in which the re- spondents described the methods used are enlightening. A male respondent said, “I am still clinging to the values that my par- ents have given to me, that is, “met de hoed in de hand, kom je door het ganse land” (a figurative expression meaning with friendliness you will get everywhere). For him this phrase en- compasses an important value. One fe male respondent welc omed the researcher to her house by saying, “Please come in, take off your hat and take a seat; you will have all my hospitality”. It seems the family values passed down by Indo parents play a big role in the ideas of the Indo respondents in this study with re- gard to their parental duty for their own families, as well as for the ways in which the respondents themselves conduct their daily lives. The second most common method, which was chosen by the respondents to keep the Indo culture alive and maintain the con- nection to Indonesia for their children and families was by tell- ing stories about past experiences in, and talking about, Indone- sia. Some of them keep reminding their kids that they are of mi xed blood, so that they will feel comfortable identifying themselves as Indos. Thus, the importance of the Indo culture for future genera- tions starts from how each existing Indo family itself values the culture. In this study, most of respondents have strong feelings towards the Indo way of life and its norms and values; and t hese are important for them to hand down to their children and to future Indo generations. Conclusion Finally, it is useful to summarise a few of the most important points about the role of Indo clubs, foundations and organisa- tions, as well as about the integration of Indos into Dutch soci- ety, to conclude this section. First, while the retired Indos of The Hague and its surround- ings profiled in this study have various reasons for joining clubs, it is significant that 50% of the respondents do belong to some type of club. Moreover, Indo clubs are clearly the most popular among them. Most of these are social clubs to meet other Indo people for leisure. In some ways as well, the clubs also play a role in preserving Indo culture by organising differ- ent kinds of cultural events, which relate and connect these people to the past and their culture. Most leisure facilities available to the population interviewed for this study where they live are those facilities available to the general public. The Indo people are considered fully integrated into Dutch society by the national and local governments, so no special facilities supported by government exist for them. For those who want to participate in leisure activities with other Indos, private or foundation supported Indo clubs near their places of residence exist in The Hague and its surroundings. The Indo-Europeans of this study are Dutch citizens, who have resided in the Netherlands for over 40 years, but who have a different culture from the ethnic Dutch and have formed a distinct subculture in Dutch society. The Indo culture, accord- ing to the respondents, is a mixed European and Asian one, with tight family bonds and close friendships forming impor- tant elements to treasure in their lives. A social life with friends and family is an extremely important leisure activ ity for most of the respondents. Having a different culture from the ethnic Dutch and having moved from their Asian homes to a new place in Europe, the Indos of this study, all of whom are now retired, needed to ad- just quickly and adapt themselves to settle in and build new lives. All of the respondents in this study have done very well in this regard. However, they retain their Indo culture and main- tain it within their families, hopefully for future generations as well. Leisure Activities among the Retired Indos and Their Significance—Findings, Analysis and Discussion Introduction to Leisure among Indos This section deals with the analysis of the leisure activities of retired Indos living in The Hague and its surroundings. This will be accomplished by considering the interview data in rela- tion to the following research questions: What kinds of leisure activities do they pursue in general? To what extent does the Indonesian culture, which was ex- perienced in childhood, influence the leisure activities of the retired Indos in The Hague and its surroundings? Do Indos feel closer to the Indonesian way of life or to the Dutch lifestyle in pursuing their leisure activities? What role do Indo clubs play in the community of retired persons? What kinds of people do the Indos mix with, and who are their best friends? Discussion Influence of Culture on Leisure Activities The choice of leisure activities that one pursues reflects indi- vidual preferences and habits that have developed since child- hood. Discussing with an individual his or her preferences and habits is not easy for all people, and it is difficult to determine if a particular situation that occurs in one person’s experience will fit another with the same background. Preferences and habits, however, can be viewed in a more general sense with regard to several aspects that may influence personal behaviour, mood and feelings towards something. First, one can look at the back- ground of a person; that is, where this person actually comes from in terms of the quality of his/her family life, the financial situation of the family while he/she was growing up, the type and cohesiveness of the community at that time, etc. This helps in identifying how leisure preferences have developed for a cer- tain individual. Other aspects, which influence one’s personal habits and preferences for leisure, are the values placed on, and strength of, tradition and culture for that person. Since people of mixed race, ethnicity or culture are very conscious of cultural values, the researcher examines culture as one of the strong  H. N. EDELMAN ET AL. 38 influences on the leisure activities of the population that is con- sidered in this study. In order to look at the leisure activities of retired Indos, the researcher pays close attention to the ques- tions: 1) To what extent does the Indonesian culture which was experienced in childhood influence the leisure activities of the retired Indos of The Hague and its surroundings? 2) What kinds of leisure activities do they pursue in general? In order to answer these research questions, it is necessary to examine a number of responses from the interviewees. Since the method- ology used in this research included not only written answers to 117 questions in interviews ranging from two to three hours in length, but also in the complete taping of all interviews, the researcher has been able to reconstruct each interview and lis- ten to it several times. This has strengthened her understanding of this unique group. Looking at the childhood background of the researched sub- jects in this study, the researcher must look back to the condi- tions of their early lives in the Dutch East Indies (now Indone- sia). One must understand how the colonial society and its com- munity structures were organised at that time to understand this group at present (See Section 2.2.1.). Indo society, then, was structured so that individuals per- ceived themselves in relation to others with regard to their rela- tive privileges, status and position in the Indo community. This was reinforced by the fact that neighbourhoods were also seg- regated according to status. Any particular neighbourhood was only for a certain kind of people with a specific status. In fact, you could see immediately the position and status of a person by the neighbourhood in which he/she lived. Thus, the majority of indigenous people lived in a kampung (village). This was separated from the Dutch settlements, so that typically Dutch kids had little or no contact with the kampung kids who may have lived just behind their houses. There were also clear distinctions between the Dutch and lo- cal school systems at that time. Aside from whites, only Indos with privileges could go to Dutch schools, although a few in- digenous people with status were exceptions and were able to attend. Other poor Indos who lived in a kampung (village) and almost all indigenous people were excluded, however, and had little education beyond the most rudimentary. Thus, at that time if an Asian was able to attend MULO (junior high school) she/he was considered relatively well educated. To reach the HBS level (senior high school) was rare and considered very good fortune. According to the social profiles of this study, then, the Indos interviewed are rather well educated for their generation. Ranging in age from 56 to 85, and with a mean age of 69.6, all 40 have completed a minimum of MULO, with 34 having completed at least HBS/MTS. Of the 40, moreover, 15 completed some kind of non-academic, but post-secondary school, and 8 completed university or another tertiary educa- tion. This is also reflected in the professions of the interviewees and their last jobs prior to retirement. None, for example were factory workers or manual labourers. Their last positions in- cluded many with middle level administrative positions. These included: 1 laboratory assistant, 1 postal employee, 9 secretar- ies and typists, 9 ad ministrative clerks at various levels in min- istries or private companies, 1 technician, 1 communications of- ficer for the municipality of The Hague. Howe ver , so me had pro- fessional positions. These included: 1 director of a foundation, 1 high-ranking p olice officer, 1 graphic desi gner, 1 engineer with a construction company, 1 technical officer on a Delta Works project, 1 chief ship’s engineer, 1 cost estimator for a construc- tion company, 4 teachers, 1 controll er for social insurance, 1 naval officer, 1 army officer, 1 exploration geologist, and 1 psycho- logist. Two were housewives. Also according to the social profiles of those interviewed, it is clear to the researcher that all the interviewees had experi- enced the Dutch school system during the Dutch colonial pe- riod in the East Indies. The schools they attended were mixed schools. Although they were primarily for the Dutch, Indos with Dutch nationality and privileged Asians were allowed to attend. The respondents also indicated that they lived primarily in mixed neighbourhoods and had a social group of friends that was somewhat mixed. However, further probing exposed the fact that most of their friends were Indos, with only a very few who were white Dutch or local Indonesians. Thus, Indos lived mostly within their own community in the East Indies, with its unique mixture of Western and Eastern lifestyle. Their income was also at a level between that of the Dutch and Indonesian ethnic groups in the East Indies. At present, in their retirements, their individual income is well distributed, although single men tend to earn more than single wo men, and couples also do rather well – better as a group than even the single men (although the income is for both). Moreover, all 10 couples own cars, com- pared to 5 of 10 single men and only 1 single woman. Currently, the daily life of Indos in the Netherlands is greatly influenced by the Dutch lifestyle. All but one (a Buddhist) are Christian (with 22 Catholic and 17 Protestant), and not Moslem as most Indonesians, for example, although only 28 of them practice religion actively, which is a higher percentage (70%) than the Dutch population as a whole. The Dutch lifestyle, of course, means more than just religion, and some basic elements are different from those of the East Indies. The researcher iden- tified these elements during her five years of residence in The Hague, and they were confirmed by interviews with two Dutch academics. One is an engineer with many years overseas ex- perience in Indonesia and elsewhere, and the second a univer- sity lecturer in Rotterdam, who has lived half his life in devel- oping countries. First, it is important to highlight the fact that the whole edu- cational system in the Netherlands is focussed on developing thoughtful and independent individuals. Dutch schools do not emphasise the institution of the family as the cornerstone of so- ciety as in Indonesia. This also means the Dutch are taught to be self-reliant, but also open to different views. This might be one of the reasons it is a relatively liberal society. The Dutch educat ional system is reflected i n the way the Dutch spend their free time and their vacations. Normally, there is not a lot of pressure on children, especially after they become teen- agers, to spend leisure time with the family, although it is ap- preciated. The choice is, generally speaking, that of each indivi- dual. Sometimes the older children spend their leisure with the family and sometimes with their friends. However, Christmas and Easter are special times when entire families come together. Another Dutch characteristic is that they prefer to spend their leisure time in small groups or with the nuclear family of par- ents and children. Huge dinners are not a common practice, and the Dutch normally cook just enough for the people present. In addition, dinner is normally not more than one hour. After the meal, family games, especially board games, as well as puzzles, are very popular in Dutch families. However, once again, it is normal that each individual decides what he or she wants to do. Youngsters along with their friends are used to spending their evenings and nights in pubs and discos. Parents normally stay home with the younger children. They do not go out to- gether as families. Finally, although restaurants are gaining in popularity, the Dutch still don’t visit them as regularly as peo- ple in many other countries.  H. N. EDELMAN ET AL. 39 Nevertheless, because of their unique background, the Indo lifestyle is different from both the pure Dutch and the pure In- donesian. Whether they initially seem characterised by only a trace of, or seem heavily influenced by the culture of the former Dutch East Indies, because of being born and spending part of their lives in Indonesia and having Indonesian blood in their veins, their habits, traditions and values are Indonesian-influenced. How much they have been affected, however, depends on sev- eral factors. The se need to be discussed before getting int o more detail about how much and in what specific ways Indonesian culture influences the lifestyle and leisure activities among the Indos in this study. First, the influence of their parents during socialisation in childhood is one of the factors, which plays a big part in their current lifestyle and habits. Moreover, having lived in pre-In- donesia during childhood and having Indo and Indonesian friends throughout their lives has helped determine their habits and values, as well as their outlook in life. In addition, the bad experiences of childhood or youth spent in the Japanese camps and the upheaval of the war of independence in Indonesia (i.e., the Bersiap Period) are important factors. Of the 40 respon- dents, 34 have experienced one or both of these events, which has had a significant impact on the lifestyle of this generation of Indos. This last experience, however, is different from that of both the Dutch and Indonesians. The independence movement was, as would be expected, a national movement characterised by anti-Dutch feelings. Those Indos who stayed in Indonesia were left with only Indo and Indonesian friends, because most of their few Dutch friends went home to the Netherlands. This pe- riod of time was the worst and hardest time for the Indos. Once again they had to face tragedy in life, which was even harder to bear than the period spent in Japanese camps. Knowing that the Indonesians were friendly people before the war, it was hard to adjust to their changed attitudes. All of a sudden, they were unfriendly and considered Indos as their enemies, because they were close to the Dutch. For example, a widower who retired as a chief ship’s engineer responded to the question: What does the “Bersiap Period” mean to you? As follows: I could not imagine what was happening, you know. I was not educated or raised up in thinking politically, so I never knew that the country where I was living in belonged to somebo dy else. I thought it belonged to the Dutch. At that time I was 18 years of age that I could not imagine the hostility. In fact, I was con- fused about what was going on and what was going to happen to us. After the war with the “Japs”(Japanese), and then faced with local Indonesians as enemies, it was a difficult time for everybody, and for children especially. A retired widow, who was formerly the head secretary of a metal company said: It was a very hard and difficult time, because (“Ik heb be- wust gemakt”(sic)) I became conscious that the Indonesians changed their behaviour towards the Dutch people and also to- wards us as Indos. They were enemies at that time. At the be- ginning they were okay, but later on they became bad towards us, and the Indonesian revolutionary youth soldiers, the “Pelopor Pemuda” also started killing the Japanese people. In the end the Indos had to choose whether to stay in Indone- sia as Indonesians or to leave for the Netherlands as Dutch. Ei ther way, it was really difficult for the m to choose. They loved Indonesia as their country and at the same time they wanted to be Dutch. Those who left, such as the subjects of this study, aban- doned a country which they loved and to start a new, radically different and very uncertain life in the Netherlands. A married male, who retired as a controller for the social insurance au- thorities, was 20 years old when came to the Netherlands with his family in 1957. He was asked why he came to the Nether- lands and answered It was because we had to leave the country. Life in Jakarta was no longer safe for all of us as Indos who carried Dutch citizenship. The school was also closed. You k now , it was really difficult to go from there, but we had to. He was also asked how he felt when he and his family left for the Netherlands and why, and he answered as follows: I felt very bad of course, because I had to leave my whole life, which I spent in Indonesia, behind, and at the same time I did not know what to expect in the Netherlands. In spite of what we learned and heard about the Netherlands, we had never lived in the country. You know, especially for my father, who had to search another job straight away, it was very difficult. Another widow, a former administrative clerk, who came to the Netherlands in 1949 as a married woman with three chil- dren, had different reasons for why she and her family had to leave the East Indies (Indonesia). This widowed woman said: I left the country because it became more and more difficult for the family and I to remain in Indonesia. We had to choose whe th e r t o be “warga negare” (Indonesian) or to leave the country. It was really a hard choice to make for everybody, I guess. However, because of my education, which was European or Wes- tern, I chose to leave the country. I also did it for the sake of my children’s education. She continued to express her feelings when she was asked how she felt when she and her family left for the Netherlands. She explained: It was very sad and difficult, because I had to leave my mother and mother in-law behind. We also did not know what would happen in the Netherlands. I heard that it was a cold country with a lot of rain. At that time, I thought well, it was okay for only 10 months, but I did not know that I had to stay here forever. When you think back, you realise how stupid I was to think that way. In answering the research question posed above, it is neces- sary to compare the leisure activities of childhood to those ac- tivities pursued by the study population at present to determine if there is relationship between the past and the present. In ana- lysing the transition from childhood to adulthood among the retired Indos in this study, it is very difficult to see any continu- ity of leisure activities throughout the childhood, adolescent and adult periods due to war, revolution and immigration. It is significant to this research in that the absence of normal child- hood and adolescent development is one of the factors, which may influence the lifestyle and leisure activities of the retired Indos in and around The Hague. Nevertheless, the researcher has been able to analyse their childhood until WW II broke out In spite of those difficult times during the war, the respon- dents reported happy childhood and adolescent experiences as part of their special memories of their early lives in Indonesia. One of the characteristics of this was high club membership. Looking at their responses to the question: Were you a member of a club when you were in adolescence? 67.5% (27 of 40) indicated membership. Those who did not belong were either too young or already in Japanese camps. The most common club activities listed by interviewees were mostly scouting and student club activities, which were popular among respondents of both sexes. Sports activities, such as playing tennis (35%) and soccer (30%) were popular among the boys who joined athletic clubs. Swimming, badminton, hockey,  H. N. EDELMAN ET AL. 40 yachting and rowing were also pursued by boys and girls on an individual basis. There were 17 respondents (42.5%) who par- ticipated in scouting (N = 13) and organised student club activi- ties (N = 4), split almost down the middle, with one more female than male. The explanatory factor for such high membership in the scouts is the fact that the scouting programs were related to the church (since most Indos are Christian) or school. Thus, they were relatively inexpensive to join and participate in activities. Another reason is that there were not many organised activities at that time. Most of their friends joined the scouts, and these groups provided opportunities to meet other people. The fol- lowing are some responses when the interviewees were asked whether they were members of a club during their youth, why and what kind of club. One widower, who was a retired com- munications officer for the municipality of The Hague, said: Yes, I joined the boy scouts some time ago, so that I could get together with other kids. Another reason was that because I had no money to join other clubs and very little money to spend for their activities, the scouts were good (because joining was free). At that time, we did not have much money, and to join a club was out of the question for me. A widow, who was a retired director of a foundation, said: Yes, I joined the scouts, a student club and other kinds of clubs, such as a dancing club and a sports club. I joined the clubs because of their activities and to meet other kids. A married male, who was a government employee of the Mi- nistry of Education, said: Yes, I joined a Catholic youth club. It was actually the boy scouts. You know, I joined the scouts because the Priest asked me to be the leader of the group. Finally, a married female, who had been a high school tea- cher, said: Yes, I was a member of the scouts and a swimming club. I joined the clubs because I liked to organise scouting activities, and, of course, I liked the sport. However, when the respondents were asked several questions, which related to their leisure activities in adulthood in the Ne- therlands before retirement, their answers showed a less par- ticipatory pattern. The questions of interest here are: 1) What kinds of activities did you do when you were not at work? 2) What ty pe of acti vi ty di d you c onsi de r lei sure? The responses to those questions have shown that there is a break with childhood and adolescence in that Indo adults in the Netherlands partici- pate far less in formally organised activities. A widowed former high-ranking police officer (police commissioner) was asked what kinds of activities he did when he was not at work. He responded as follows: I did sports such as tennis and football. I travelled with my family to see other European countries, visiting friends and family, went to the cinema. My wife and I often went to parties and out dancing. He also mentioned the types of activities that he considered as leisure during his adulthood before reti r e m e nt a s foll o w s: I considered sports as part of my leisure, and sight seeing by driving around weekends was also leisure. Reading and listen- ing to music, particularly country music, was leisure too. A few relevant questions were also posed regarding activities after retirement to see whether there would be a continuation of their adult leisure activities into old age. These questions are: 1) How do you fill your time daily? 2) What kinds of activities do you do for leisure? It was found that, indeed, adult activities continue to a certain extent into retirement. Social and family oriented activities such as visiting friends (55%), going dancing (30%), helping other people (35%), going shopping (45%), looking after grandchil- dren (22.5%), visiting family (30.8%), playing cards (17.5%) and cooking (22.5%) are the major leisure activities of Indo adults in The Hague and its surroundings, and they remain an important part of life among the retired Indos in this study. The retired police commissioner, for example, said: These are basically what I do to fill my time daily: I take my time to do things, and I do a lot of walking, reading, and lis- tening to music. I am very lucky that I have a lady who comes to do household work and cooking for me, so I don’t have to worry about it. He continued: I think leisure activities for me now are travelling, reading, walking, listening to music, and watching television sometimes. In contrast, participation in those activities related to physical movement, such as tennis, badminton, swimming, soccer and rowing, which began in y outh and continued to some extent into adulthood, has declined and in some cases even ended. While some physical activities among retired Indos, especially tennis (20%) and swimming (7.5%), are still pursued to a certain ex- tent by mostly male Indos, most sports have been replaced by other forms of physical exercise, such as walking (37.5%; mostly men) to keep healthy. Moreover, married man and married women among the re- tired Indos in this sample display a somewhat more active lei- sure lifestyle than their single contemporaries. While the single wo men interviewe d in this study na med visiting friends, watchin g TV and reading as their most significant leisure activities, mar- ried women were much more likely to go out to parties, go dancing and travel. Analogous to the women, among single men, read- ing walking and visiting friends were the most frequent leisure activities, while among married men, partying, dancing and trav- elling were also important. For example, a widower, who re- tired as a construction company engineer, when asked what his current leisure consists of, said: I visit friends. Also, my leisure is reading, gardening and watching television, but not much, say 1 to 2 hours, which is mostly news and sports. The same question was asked of a married, former explora- tion geologist. He responded: Now that I am retired, almost everything I do is for leisure. For example, I get up late, read a lot, do puzzles, and have nice food with family or friends, because my wife is a good cook. Also, I play tennis twice a week, and I do a lot of walking for my physical exercise. When he was asked what types of activities he did with his wife and why, he answered: Well, we play tennis together now, since my wife has been taking lessons. It is nice! We go out with the family or some- times just ourselves to the beach. We visit friends and we go out for movies and to restaurants regularly. You know, there are a lot parties among our Indo friends, so we go to parties and what we like to do is to go to a mountain resort and travel to Asia to visit our friends and to see the countries. Maybe this is because we lived in Singapore, Indonesia and visited other countries for my work in the past. Of course, with ageing, sedentary leisure activities have also developed among retired Indos. Watching television (42.5%) is one example, but this is characteristic more of single and mar- ried women than among single or married men. Reading is the single most popular leisure activity among the retired Indo, comprising 27 out of 40 respondents (67.5%) in this study. The next common leisure activity is visiting friends as a social ac-  H. N. EDELMAN ET AL. 41 tivity (55%). A gathering with food is one of the most important social occasions within the Indo community. Indos like getting together to make a pleasant evening. With their hospitality and warm feelings of welcome extended to visitors to their homes, Dutch Indos are quite different from the Dutch in general. This custom comes from the Asian side of their family histories. Nevertheless, while the general pattern of high participation in sedentary-social and sedentary-isolate activities in old age, coupled with a decline in pursuing active-social (i.e., physical activities such as sports) may be characteristic of most adults in later life (Leitner & Leitner, op. cit.), regardless of their cul- ture, the respondents accept their increasing confinement to their homes more easily than most Dutch. The reason for this is the fact that their close family bonds mean that a large portion of their leisure has been spent receiving visits from their fami- lies and relations, or visiting them, throughout their lives. Thus, they simply receive more visits than they make as they age. This aspect of their culture plays a positive role in enabling ageing Indos to adjust to decreasing mobility. After analysing the retired Indos’ leisure that to some extent culture influences their leisure activities, especially in relation to social life. Particularly in old age the social aspects of leisure become extremely important in life, because retired Indos have more time to socialise. Moreover, the circumstances of ageing, such as being in poor health, having limited mobility and not being able to drive make them feel the importance of social life even more. The fear of being isolated is very strong, due to the importance placed on the extended family and social life in Eastern cultures. Leisure as Social Life Leisure activity can be considered a tool for an individual to achieve his or her goals in life, and the researcher believes that deriving satisfaction from one’s leisure will lead to a better and happier life. If there is no leisure in one’s life, there is only work, but working continuously is impossible. Any living en- tity needs food, water to drink and rest from the physical and mental wear and tear of living, so this time away from work is crucial to recharging one’s batteries, so to speak. During peri- ods of rest, a person can do whatever he or she wants. This freedom of choice defines an activity, which is conducted then as “leisure”. The meaning of leisure itself is quite broad and depends on one’s own opinion and feelings, which are very often difficult for a person to define. Consequently, it is not the purpose of this chapter to define leisure in any narrow sense. Instead, the researcher utilises the word in this study as having a wide and flexible meaning according to the individual per- spectives of the subjects interviewed. There are many reasons for pursuing any particular leisure activity for an individual, and the choice depends very much on personal preference, which is tied to the personal background, habits, culture and social sphere of the individual. Having said this, however, for the purposes of the analysis in this study, it is necessary to review several reasons for pursuing a leisure activ- ity in general in relation to the retired Indos as the subjects of the study. These are: 1) leisure as a psychological factor in achieving a happy and satisfied life; 2) leisure as social life; and 3) leisure for a healthy life. The first purpose of leisure has been and will continue to be mentioned in general discussion throughout this thesis; while the second is the focus of this section, and the third will be analysed in the following section. It is necessary to look at the relevant research questions to be able to elaborate the issue: 1) Do the retired Indos feel closer to the Indonesian way of life or to the Dutch lifestyle in pursuing their leisure activities? 2) What kinds of people do the Indos mix with, and who are their best friends? 3) What kinds of lei- sure activities do they pursue in general? In order to analyse the retired Indos’ way of life, it is first necessary to look at the answers to the research questions mentioned above as they have become clear through the conduct of interviews with the forty subjects. The first important interview question related to these re- search questions considers how they felt when they and their families left for the Netherlands. Their answers vary according to their feelings about and abilities to cope with the terrifying experiences of the Indonesian independence upheaval. One of the respondents who is single and retired as administrative clerk from the Ministry of Justice in The Hague was asked how he felt when he and his family left for the Netherlands. He said: I was 18 years old when I left Indonesia, and it was in 1955. I felt so sad and even more when we arrived in the Netherlands. I cried and was upset. I wanted to go back to Indonesia at that time. We arrived in winter, so you can imagine it. It was cold, and there was no sun. The whole situation really made me upset. The next response is from a widow who dedicated herself to the family as a homemaker. She expressed her feelings as: You know, I was glad that I was able to go to the Nether- lands. It was difficult to be Dutch during the period after the war and especially was hard for my husband who was Indo and had fair skin and hair. We could not buy anything and food was difficult to get. Everything was chaos and it was a hard time I had to say. The Table 8 below summarises the feelings that were experi- enced b y th e r espond ents wh en t hey lef t In dones ia p erman en tly. The reasons why they felt 1) happy and glad; 2) sad and bad; or 3) experienced mixed feelings, which were expressed by the respondents during the interviews, have been classified into groups of similar responses. Those people who felt happy and glad to leave for the Netherlands had as their reasons the cir- cumstances that reigned in Indonesia at that time. The situation in Indonesia was very chaotic after WW II. The Dutch East Indies had been occupied by the Japanese; and when the colony reverted to the Netherlands, the indigenous Indonesians began to rise up against their rulers. They wanted the country for themselves. Everything was in chaos, and the rule of law de- generated. There was no effective government to control the country; and the public institutions, such as schools, churches, etc., were closed. It was difficult to get food, and the overall situation was deteriorating rapidly. The anti-Dutch movement increased in size and intensity, and fighting broke out every- where. The safety of the Dutch and of those friendly with the Dutch was jeopardised. Being Indo was very difficult, because of their mixed background. While they were considered Dutch because one parent was Dutch or partly Dutch, they were si- multaneously close to the Indonesian way of life. Because of Table 8. Respondent feelings upon leaving Indonesia. Single Female Single Male Married Female Married Male Total Happy & G l ad3 3 3 1 10 Sad & Bad 7 5 5 6 23 Mixed Feelings0 2 2 3 7 Total 10 10 10 10 40  H. N. EDELMAN ET AL. 42 these circumstances, some of the respondents felt safe, free, and glad to be able to get away from Indonesia at that time. Those who felt sad and bad to leave Indonesia cited personal reasons. They had to leave behind an Indonesian mother, grand- mother or friends, as well as their property and belongings. Most of them also had strong feelings for Indonesia and its people. It was their own country, and it was part of their lives. Those respondents who had mixed feelings when they left Indonesia were sorry to leave their birthplace behind but wanted to improve their lives. They felt relieved that they were still alive after all the tragedy they had experienced, but they none- theless felt sad to leave Indonesia, which they loved, behin d. Looking at the majority of the respondents’ answers, their feeling of sadness regarding leaving Indonesia is an indication that they had strong feelings towards the country. While this feeling may have faded slightly, deep down, it is still there for most of them. To strengthen the impression gained from their answers to the previous question, the interviewees were asked: Do you still consider yourself part of Indonesia? The answers strongly con- firm the findings of closeness to Indonesia among Indo retirees. Answering yes to this question were 77.5% or 31 out of 40 respondents, while only 20% (8 of 40) answered no. Only a single respondent, representing 2.5% of those interviewed, had mixed feelings. Looking at the majority answer indicating that Indos in The Hague and its surroundings still feel close to In- donesia, the next question to pose is why? All of them answer that it is because their roots are there, and they still have Indo- nesian social habits, moral values and ways of acting within their families. Thus, a strong feeling towards Indonesia can be an indication that a respondent’s way of life still has traces of Eastern values in the home, and has not been completely assi- milated into the Dutch culture. For example, a widow who re- tired as a teacher explained: Oh yes, definitely, I am still part of Indonesia, because an important part of my life was spent in Indonesia. You know, some of my roots are Indonesian, and it will always be so. There are other indicators that Indos have a mixed culture of Western and Eastern values. For example, when they were asked what kinds of dances did you learn in your adolescence and why, it was not surprising that 38 respondents or 95% said that they had learned Western dances such as ballroom dances and modern dances. One respondent said he had learned Indonesian traditional martial arts dance (pencak silat), and 1 respondent answered none. There were also 2 female respondents who learned both Indonesian traditional dance and Western dances. The reasons they learned ballroom dances or modern dances were that they formed a part of their education and were also a must thing to do socially in those days. In this sense, learning western dances was just like learning how to play the piano; it was done to demonstrate that one belonged to a certain level of status. Of all 40 respondents, 17% or 42.5% played musical in- struments. Of these 17%, 10% or 58.8% learned to play the piano. The other instruments played included the guitar, played by 5 respondents; the harmonica, played by 4; the drum by 3; the ukulele by 2; and the bongo and bass by 1 each. In addition, 3 out of 40 respondents learned how to play a traditional Indo- nesian instrument (suling). Some of the respondents still play their instruments as a social activity with their Indo friends and at least 3 play in small bands as a hobby. An important question then arises: who are their friends most often? Their responses show that they had mostly a mixture of friends, but with only a few pure Dutch and pure Indonesian friends during childhood, and that this has continued into ado- lescence and adulthood. Moreover, this pattern has lasted into retirement. Of the 40 subjects in the study, 87.5% (35 out of 40) declared that they have a mixture of friends, and 5 of the re- spondents said that they have Indo friends only. Most of the re- spondents who have mixed friends said that they have more Indo friends than Dutch or Indonesian friends. A retired chief administrator from the Ministry of Education was asked if most of his friends are Dutch, Indo, Indonesian or mixed. He said: Well, I have mixed friends. However, most of them are Indos. Interviewer: Are they new friends or old ones? Respondent: They are old friends. Most of them I know from before the War when we were in the East Indies. A married man who worked as social insurance controller was asked the same question and claimed: I have mixed friends, but I must admit that my best friends are mostly Indos. They are both old and new friends. I know most of my old friends for more than 20 years and the new ones for several years. The most common leisure activities among the retired Indos in The Hague and its surroundings were mentioned in the pre- vious section. Vi siting friends as a social activity comprises 55% of the respondents’ leisure. The other leisure activities, which are pursued by the respondents as part of their social lives, are visiting family (30.8%), going dancing (30%), playing cards (17.5%) and helping others (17.5%). Generally speaking, after interviewing them, the researcher formed the impression that most of the retired Indo people in this study like parties; that is, getting together with friends to eat and chat as part of social life. They like to hear music, to dance and to have a good time with their friends. Leisure for a Healthy Life The research questions relating to the respondents’ reasons for pursuing leisure for their health are not specific. Rather, their reasons for answering the general questions about why they pursue their leisure activities in general have been ana- lysed for this purpose, as have their feelings towards the active- ties themselves. For example, the researcher asked the respon- dents, Why do you do these activities? The answers that were given were then grouped according to their connotations. The answers do not add up to 40, because some interviewees had more than one reason: 1) They pursue leisure to fill their empty time with activities (N = 17); 2) They are involved because they have plenty of time now to do the activities that they had always wanted to do in the past (N = 8); 3) They find that the activities give them pleasure and/or help them relax (N = 19); 4) They pursue the activities in order to make social contact with others so that they don’t feel lonely (N = 4); and 5) They do the leisure activities for their health; that is to keep in shape, stay active and stave off depression from being old (N = 24). It is obvious from the pattern of answers that the respondents clearly see the value of leisure to their physical and mental health. The answers that fall in category 5, given by the greatest number of respondents (i.e., 24% of 40% or 60%), explicitly recognise the health value of leisure activities. In addition, those answers falling into categories 1 and 4, 17 and 4 respec- tively, or a total of 21% or 52.5% of respondents implicitly recognise the health benefits of leisure. The next question posed to the respondents was: Are you satisfied with your current leisure activities? Give the reason  H. N. EDELMAN ET AL. 43 why? It is important to know how satisfied the retired Indos are in pursuing the leisure activities at the present time and why, because the results should confirm that the health benefits of leisure expected by the respondents have in fact been realised. The results show that 80.5% (34 out of 40) are satisfied with their current leisure activities, while only 6 of them are not. Those who are satisfied in pursuing their leisure activities have demonstrated that they are enjoying the retirement. They are happy to have more time to enjoy family life and doing things with their friends (6 of 34), and to do things that they could not do before retiring (N = 3). In addition, they feel that they have plenty of enjoyab le a ctivities (N = 25). To illustrate, a widower who retired as cost estimator for a construction company was asked several questions as follows: Interviewer: What kinds of activities do you do for leisure during your retirement? Respondent: My leisure activities are swimming, tennis, vis- iting family and friends, reading, playing cards (bridge), and going on vacation. Interviewer: Why do you do these activities? Respondent: Well, because I have more time now and also to keep fit. Sometimes I wish I had more time for all the activities I like. Interviewer: Are you satisfied with your current leisure ac- tivities? Respondent: Yes . Interviewer: Please, tell me why. Respondent: It is because I feel better and happy with the additional time that I have had since I retired. I can use it for doing things, which I like. I am also happy because I remain healthy. It seems, then, that most of the retired Indos in this case study have a sufficient number and quality of activities and fol- low an active social life, with their family and friends as the centre of attention. However, it is important to mention here that the existence of an excellent state pension and retirement plan in the Netherlands makes it possible for the average retired person to live comfortably. The elderly, by and large, are not threatened by poverty. Moreover, the Dutch public transport system is well connected and runs almost everywhere, so that retired people can do things easily by using buses, trams and trains. They are, therefore, not bound to their houses. For those respondents who are not satisfied with their leisure activities, several health-related reasons stand out. A few of them have physical problems that limit them from doing what they want to do in their leisure time, while others feel depressed from having not having enough productive things to do. Some suffer from depression in retirement because they miss their late spouses or their old friends in Asia. One single female re- spondent, who retired as a secretary, when asked whether she was satisfied with her current leisure activities said: No, I am not satisfied. You know in a way I am handicapped because of my health condition, which prevents me from doing things. I like to go everywhere and do some sport activities, but I can not do them any more. The results presented in this section, however, show that the retired Indos of The Hague and its surroundings are, generally speaking, happy and satisfied with their leisure activities. They enjoy their retirement, and recognise that physical and mental health contributes to it. A Typology of Indo Leisure Lifestyles What emerges from this analysis of the leisure of the retired Indos of The Hague and its surroundings is a typology of lei- sure styles. A typology is a classification system, that is, a way of organising ideas. It is not the only one, but it seems appro- priate here. In a typology, a researcher combines two or more uni-dimensional, simple concepts or ideas, and the intersection of the simple concepts or ideas forms a new way of examining a topic. For the purpose of this research, a typology of leisure life- styles for retired Indos is appropriate in understanding what has been reviewed so far. One might suppose that there are three such leisure lifestyles exhibited by those retirees studied here; that is, Indonesian, Dutch and Indo leisure lifestyles. One might further assume that they could be characterised by some or all of the following simple elements and concepts: 1) social roles—concept of family, role of extended family, strength of family bonds, importance of using the proper form of address, respect for older persons, value placed on helping each other and the value of hospitality; 2) personal habits—language spo- ken among the group, Asian or European manners, importance of modesty, type of food consumed at home, method of bathing, and toilet habits; and 3) leisure activities—movie-going, lis- tening to music, social dancing, party-going, eating together and visiting friends and family. One could also suppose that men and women, as well as sin- gle people and married ones, would have different leisure life- styles. To some extent, that appears to be true among the retired Indos of The Hague and its surroundings. Although both men and women are club members (or not), men participate more in sports (e.g., badminton and tennis) and other outdoor activities (e.g., walking, cycling and gardening) than women, while wo- men are more involved in indoor pursuits such as socialising with friends and playing cards. Couples also are more likely to go on trips, to go out to dinner, dancing or a party and to par- ticipate in more group-related social activities of the Indo social clubs than single Indos. Moreover, it might be assumed that with a strong Eastern cultural component, that the male member of a couple would dominate in the choice of leisure. However, this does not ap- pear to be the case. Both men and women seem to be the domi- nant or subservient partner depending on the particular couple. Thus, the research undertaken here has yielded a somewhat different picture than the assumed Indonesian, Dutch and Indo leisure lifestyle split one might expect. The key factor seems to be the degree of integration into Dutch society. The first two groups of elements and concepts outlined above (i.e., social roles and personal habits) are merely manifestations of this integration, which the respondents have verbalised through their views on how they identify themselves (Table 2), how they characterise Indo culture (Table 3), how close they feel to In- donesia (Table 4), the importance of Indo values and habits to them (Table 5), and the aspects of Indonesia missed by them (Table 7). What these and other feelings of self identity expressed by the respondents indicate is that it is more meaningful to classify the population of this research into a typology of two rather than three groups with regard to their leisure lifestyles. These groups can be characterised as Traditional Indo and Indo-Eu- ropean Dutch. The first group remains more classically Indo in self-concept (Indo), social roles (strong family bonds) and per- sonal habits (Eastern toilet habits), while the second group of individuals feels both Indo and Dutch, and this is apparent by its way of life. Thus, the second group has a mixed Indo and Dutch self-concept, Indo social roles (strong family ties) and some additional Dutch personal habits (e.g., Western toilet ha- bits). The styles of leisure of the sample studied here seem to  H. N. EDELMAN ET AL. 44 exhibit this dichotomy as well. The first group is somewhat more bound to family and old, exclusively Indo friends than the second, which is more likely to meet new people in Indo clubs and partake in more Dutch-style leisure activities (e.g., attend- ing the theatre) with their Indo friends. Of the 40 respondents in this study, 20 were clearly Traditional Indo, while 18 were Indo- European Dutch. The remaining two were in neither group completely, but could be better considered as members of the latter group who were the closest to being either Dutch (N = 1) or international (N = 1) with respect to their leisure lifestyles. The typology outlined in this Section is summarised in Table 9 below: There is no indication given by any of those retirees inter- viewed that they exhibit a totally Indonesian leisure lifestyle. This is to be expected, since they were never Indonesian, but were always considered as a distinct and separate group in the Dutch East Indies. There is, however, also no indication that any of the respondents are completely assimilated and now pursue a totally Dutch lifestyle, including its leisure, although two do seem to lean somewhat more in this direction. Conclusion What the analysis presented in this section and the typology summarised in Table 9 show is that there is definitely a unique Indo lifestyle among the retirees studied here. The respondents in this study have clearly been influenced by both Western and Eastern culture in their habits, way of life and preferences for leisure activities. The Eastern, predominantly Indonesian, cul- ture influences their leisure activities in that social life plays a critically important role. Getting together with friends and fa- milies, having a meal together in a small gathering or big party with dancing, etc. are primary leisure activities among them. In addition, the respondents have expressed that they are satisfied with their leisure activities, and generally enjoy very active retirement. As a result they pursue leisure activities which en- able them to be healthy in both body and mind. Nevertheless, with 36 of the 40 respondents feeling close to Indonesia but nonetheless wanting to remain in the Netherlands, it seems that the older they get, the closer they feel to the cul- ture of their birthplace. This is possibly why they spend more time with other Indos than with the Dutch. At the same time, while there is a different weight given to the various elements of this leisure by members of the two different leisure lifestyle groups, this is really only a matter of degree. The leisure life- styles of the interviewees remain remarkably similar, despite the variations observed. Conclusion and Recommendations Introductory Comments This chapter first summarises the conclusions drawn from the findings of the research (Section 5.2.). It then outlines recom- mendations for policy makers derived from them, and, finally, suggests directions for further research that would provide ad- ditional information in order to make Indo retirement in the Ne- therlands a more satisfying experience (Section 5.3.). It should be noted here, as well, that the lessons learned from this re- search might be useful in considering how to meet better the leisure needs of retirees from other minority groups in both the Netherlands and in other Western European countries. Table 9. Typology of Indo leisure lif es t yl e s . Traditional Indo Indo-European Dutch Social Roles Family concept Very strong Strong Role of extended family Very importa nt Important Strength of family bonds Very strong Strong Proper form of address Very import ant Important Respect for elders Very import ant Very import ant Value of mutual help Very import ant Important Value of hospitality Very importa nt Very important Personal Habits Language o f g roup Dutch & Indonesian Dutch & Indonesian Manners Eastern Eastern & We stern Importance of modesty Very important Important Type of food at home More Indonesian More Dutch Method of bathing Eastern Western Toilet habits Eastern Western Leisure Activities Movie-going Yes Yes Theatre-going No Yes Music listened to Eastern & Western Eastern & W estern Social dancing Often Sometimes Party-going Often Sometimes Eating together Very important Important Visiting friends & family Very importa nt Important  H. N. EDELMAN ET AL. 45 Conclusions This section summarises the conclusions drawn from the re- search. Detailed, in-depth interviews were conducted with forty retired Indos, all of whom live in The Hague and its surround- ings. A nu mber of supplementar y interviews were also held with social workers, administrators and academic experts. All inter- views were conducted between April and July 1998 as the pri- mary research methodology for evaluating the leisure active-ties and lifestyle among retired members of this ethnic minority. The basic research concern was to explore the leisure of the res- pondents to see if their activities met their needs so that they were satisfied with life as Indo retirees residing in the Nether- lands. The interviews generated data that addressed the research questions of Section 1 and which were analysed in Sections 3 and 4. To reiterate for the purposes of this final section, the four specific objectives of this study were: To determine to what extent retiring and ageing Indo-Euro- peans or Indos have been exposed to Indonesian culture both before and after immigration to the Netherlands; To identify how deeply childhood experience in Indonesia has influenced their way of life and leisure activities in the Netherlands; To measure to what extent these Indos participate in leisure activities, which pertain to their cultural or ethnic Indone- sian heritage in their free time; and To evaluate how leisure activities can help the Indos in the Netherlands retain their original Indo culture, thereby ena- bling them to be comfortable in their new culture (i.e., Dutch culture) during retirement and ensuring satisfaction with life. The discussion in this final section, then, focuses on relating the research results and findings to these specific research ob- jectives in order to determine some possible recommendations and suggestions for leisure programme developers and for re- searchers who might undertake further study on this subject. Briefly, the general conclusions of the research are as fol- lows: Culture has influenced to an important extent the leisure and social lives of the respondents; The respondents’ social lives, which reflect Indo habits, va- lues and preferences, have become primary leisure activities among the respondents; Married retired Indos have more active social lives than either single men or single women, but single men are more active than single women; The respondents pursue active retirements, which they en- joy and fill with various leisure activities, enabling them to maintain generally healthy and satisfied lives during retire- ment; Clubs play, to a certain extent, a significant role among the respondents who are members. The clubs are important in their social lives as a place to meet other Indos, engage in leisure activities together and help to preserve the Indo cul- ture through the organised cultural events, which take place there; Family and friends, who are mostly Indo, play the most im- portant role in social life and leisure; Current leisure facilities, provided by the local municipality, are generally used by all local citizens as part of their gen- eral leisure and recreation; There are not many leisure facilities in the communities where the respondents live that can provide even occasion- ally programmes which relate to the Indo people; The respondents are considered by most Dutch to be well integrated into their society. Some would probably also con- sider many to be assimilated if they did not know them well. However, the interviews conducted by this study present a picture of only partial integration and no assimilation at all among the members of this generation; The Indo culture, along with its habits, norms, and values are evident everywhere in the lives of those interviewed, and it is important to the respondents that they remain ele- ments in their family lives; and This study on retired Indos in the area of The Hague seems to confirm the activity theory of ageing, which assumes that continuous social involvement is the way people adapt suc- cessfully to ageing. It also supports the continuity hypothe- sis, which suggests that there is a positive relationship be- tween aged persons’ contentment with their life situation and the similarity between their lifestyles in middle adult- hood and in old age. Voges and Pongratz (1988) refer to this as the continuation of a familiar lifestyle. Recommendations The recommendations of this research can be divided into two categories. The first considers the policy and programme implications of the work, and the second suggests future fruitful research that could be conducted to shed more light on the sub- ject. Discussion of both follows. Policy and Programme Recommendations It has not been the intent of this study to formulate detailed leisure programmes for the retired Indos of The Hague, but rather to understand existing leisure activities as an expression of Indo culture, and to determine, in a general way, if and how they lead to healthy retirement. Clearly, this sample is content, but there are improvements to be made. Consequently, the fol- lowing general recommendations are intended for those respon- sible for developing leisure programmes for retired Indos. They are based upon or related to the findings of the 40 direct inter- views of retired Indos in The Hague and its surroundings con- ducted in this study, and on the conclusions drawn from them. Obviously, they are relevant to retired Indos elsewhere in the Netherlands, and leisure planners might consider how the les- sons learned from this research might be applied to considering other minority groups in the country. The Turkish and Moroc- can communities come immediately to min d. The policy and programme recommendations of this study, then, are listed below: It is necessary to consider Indo cultural content for any lei- sure programme or its component activities for ageing or retired Indos due to the overwhelming importance of Indo culture to the mix of various leisure activities of the re- spondents in this study. Moreover, this should be the case for any group of minority retirees. Any programme or acti- vity should relate specifically to the culture, habits, norms and values of the particular people for whom the program- me is targeted. A complete leisure programme of activities for Indos or any other minority group should include a meaningful array of cultural events that can connect the specific ethnic group to its past and bring its members closer to their own culture. This should be done even though the retirees are already in- tegrated into (or appear to be integrated into) Dutch (or any host) society. Through leisure, culture can be maintained and preserved. More leisure activity, which is related to the culture of the  H. N. EDELMAN ET AL. 46 Indos and other major minority groups in the Netherlands, aged or otherwise, should be scheduled as part of the leisure programmes at the existing local facilities such as a com- munity “soos” (club). By providing different types of pro- grams for the local community, leisure would provide the local citizens with various choices to satisfy their needs and interests. In the case of Indo culture, the leisure organisers would give an opportunity to the local, ethnic Dutch people to learn about the culture of another people who reside in their country, as well as about an important part of their own history. A strong parallel can be made here between Indo- nesia with the Netherlands and Algeria with France or Mo- zambique with Portugal. All the former were major colonies that were considered, rather, as integral parts of the corre- sponding European states. All three colonies became inde- pendent after wars of libe ration, and all three European states had a large number of repatrianten. With this level of im- portance tied to Indo culture, some locally based cultural events would show how important the minority subculture is to the dominant one. Thus, eventually Indo culture could be integrated into the local society as part of the rich culture and history of the Netherlands. Indos could eventually be viewed just like other Dutch people who come from the va- rious regions of the country and have different cultures, ha- bits, norms and values. An Indische Bejaarden Huis (Indo Home for the Aged) in The Hague is a necessity, especially as the Indo retirees continue to age. It is rather remarkable that one does not exist, considering the size of The Hague itself and the large Indo population living in the city and its surroundings. The existence of an Indo Home for the Aged would expand the possible choices of accommodation for retired and elderly Indos. Considering the ageing of this generation and the adoption of smaller family sizes and dwelling units among second and third generation Indos, at some point Indo retir- ees will form a large group of elderly in need of assisted living with an Indo cultural content. There is as yet no such institution in the city. As is indicated by the results of the interviews with the retired Indos of this study, it is evident that much of the retired Indo community in The Hague and its surroundings is still strongly connected to its own culture, norms and values as part of the daily routine. Without this cultural content, the Indo elderly do not feel comfortable. It is clear that the retired Indos in this study like being to- gether with their Indo friends for the purpose of the leisure. A home will enable them to be together with other elderly Indos and feel comfortable within an Indo way of living as part of their home service. In addition, leisure activities with Indo cultural content would be more easily implemented through cultural events that could be scheduled on a regular basis. Thus, the Indo people will feel happy, comfortable and satisfied during their remaining days. In order to be effective, all of the above suggestions should be incorporated into a set of policy guidelines for recrea- tional and social services within the city of The Hague and its surrounding municipalities, as well as, where appropriate, for the local community recreation centres. It is particularly important for the government of the Netherlands, working with the city and the surrounding municipalities, to develop a programme supporting the local Indo clubs, organisations an d foundations that try to keep the Indo culture alive throug h their various programmes. Recommendations for Further Research There are a number of useful directions that future research could take. Those that are recommended include: An effort to refine, elaborate and test the dichotomous ty- pology of Indo leisure lifestyles suggested in Section 4. The first (or immigrant) generation Indo individuals of this study overwhelmingly have a leisure lifestyle that has been char- acterised as either Traditional Indo or Indo-European Dutch, in comparison to both Dutch and Indonesian ones. A ques- tion for further empirical study, then, is to determine if this remains the case among second and third generation Indos living in the Netherlands. One could hy pothesise that in suc- ceeding generations, even if the leisure lifestyle remains heavily Indo for a period, that the Traditional Indo leisure lifestyle would gradually lose its appeal to the Indo-Euro- pean Dutch one. Eventually, if it is assumed that the Indo population would become fully assimilated into Dutch life (which is by no means certain), it is to be expected that this ethnic group’s leisure lifestyle would become largely, if not completely, Dutch. The implementation of a much larger quantitative study of retired Indos covering all of the Netherlands to confirm this study’s qualitative findings for The Hague and its sur- roundings. The undertaking of a similar qualitative study of other sig- nificant non-Dutch ethnic groups (i.e., Turks, Moroccans, Surinamese—both Black and ethnic South Asian (Hindu- stani in Dutch) and Caribbean Islanders) in the Nether- lands. The purposes would be 1) to refine the methodology employed here and 2) to determine if the same general con- clusions and recommendations that emerged in this thesis could be generalised to those groups. If so, only specific, ethnic-group related findings would be different. This would have important implications for social policy in the Nether- lands with regard to the ethnic elderly. The carrying out of a similar, but comparative, qualitative study of the Turks in Germany, the North Africans in France and the South Asians in Great Britain, to confirm that the fi n dings of this research would a lso be the case in other West- ern European countries. This could have important implica- tions both for these countries and for overall European Un- ion social policy on ageing ethnic minorities. Even Italy and the Nordic countries are experiencing rapid Third World immigration, and all these groups will age in time. Only if all four of the above studies are carried out can it be ascertained if there is a lasting contribution to the science of the leisure of the elderly that has been made by this research. Once these studies are completed, broad inferences could be drawn that generalise the overall findings into theoretical constructs. References Beets, G., & Koesoebjono, S. (1991). Indische Nederlanders: Een ver- geten group. Moesson, 36. Blokker, J. (1997). De Indo en het verloren thuisland. de Volkskrant, 45. Boon, S., & van Geleuken, E. (1993). Ik wilde eigenlijk niet gaan: De repatriëring van Indische Nederlanders 1946-1964. The Hague: Stichting Tong Tong. Bronkhorst, D., & Wils, E. (1996). Tropenecht: Indische en Europese kleding in Nederlands- Indië. The Hague: Stichti n g Tong Tong. Clarke, A. (1994). Leisure and the elderly: A different world? In I. Henry (Ed.), Leisure: Modernity, postmodernity and lifestyles (pp. 189-201). Eastbourne: The Leisure Studies Associat i on . Cowgill, D. O. (1972). The role and status of the aged in Thailand. In D. O. Cowgill, & L. D. Holmes (Eds.), Aging and modernization (pp.  H. N. EDELMAN ET AL. 47 91-102). New York: Applet o n -Century-Crofts. Degazon, C. E. (1987). The relationship of ethnicity, social support, and coping strategies among three subgroups of black elderly. PhD Dissertation, New York: New York University. Derksen, E. (1994). Met kruiden en een korrel zout: Smaak en gesciedenis van de Indische keuken. The Hague: Stichting Tong Tong. Dobbin, I. (1980). Retirement and leisure: A preliminary research report. Salford: Centre for L eisure Studies. de Volkskrant (1997). Meer ouderen straks rij ker en zelfstandig er, 6. Feirabend, J., Meyer, A., Wolff, R., & Penninx, R. (1998). “Het lijkt wel alsof ze geen wensen hebben…”: Oudere Indische Nederlanders en zorg, een verkennend onderzoek. The Hague: Stichting Pelita. Geiger, C. W., & Miko, P. S. (1995). Meaning of recreation/leisure activities to elderly nursing home residents: A qualitative study. Therapeutic Recreation Journ al , 29, 131-138. Horsten, H. (1998). Bejaarde Molukkers vinden eigen woonplek, de Volkskrant, 9. Iso-Ahola, S. E. (1997). A psychological analysis of leisure and health. In Haworth, J. T. (Ed.), Work, leisure and well-being (pp. 131-144). London: Routledge. Jagt, B. B. (1991). De charme van het Indisch zijn. The Hague: Sticht- ing Indisch Cultureel Centrum. Kelly, J. R. (1990). Leisure and aging: A second agenda. Society and leisure, 13, 145-167. Kelly, J. R. (1991). Leisure. In E. F. Borgatta, & M. L. Borgatta (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Sociology (pp. 1099-1107). New York: Macmillan Publishing Corp. te Kloeze, J. W. (1990). Changing economic conditions in relation to recreation styles in The Netherlands. Paper presented at the Polish Association Leisure and Recreation International Conference, Za- jaczkowo, 25. te Kloeze, J. W. (1991). Het begrip leefen recreatiestijl in onderzoek naar recreatie van ouderen. Paper presented at the Nederlands- Vlaamse Vrijetijdsstudiedagen “Grensoverschrijdingen in de vri- jetijd”, Breda: Nationale H og e sc h o ol voor Toerisme en Verkeer, 10. te Kloeze, J. W. (1998). Integration through leisure? Leisure time ac- tivities and the integration of Turkish families in two cities in the Netherlands. Paper presented at the LSA 4th International Confer- ence “The Big Ghetto: Gender, Sexuality & Leisure”, Leeds, 10. Leitner, M. J., & Leitner, S. F. (1996). Leisure in later life. New York: Haworth. Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications, Inc. Long, J., & Wimbush, E. (1985). Continuity and change: Leisure around retirement. Lon do n : S p orts Council. MacNeil, R., Teague, M., McGuire, F., & O’Leary, J. T. (1987). Older Americans and outdoor recreation: A literature synthesis. Therapeu- tic Recreation Journal, 2 1 , 18-25. MacNeil, R. D., & Teague, M. L. (1987). Aging and leisure: Vitality in later life. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall. McPherson, B. D. (1990). Aging as a social process. An introduction to individual and population aging. Toronto: Butt e rworths. McPherson, B. D. (1991). Aging and leisure benefits: A life cycle per- spective. In B. L. Driver, P. J. Brown, & G. L. Peterson, (Eds.), Benefits of leisure (pp. 423-430). Pennsylvania: Venture Publishing, Inc. Menec, V. H., & Chipperfield, J. G. (1997). Remaining active in later life: The role of locus of control in seniors leisure activity participa- tion, health and life satisfaction. Journal of Aging and Health, 9, 105-125. doi:10.1177/089826439700900106 Mobily, K. E., et al. (1993). Leisure repertoire in a sample of mid-western elderly: The case for exercise. Journal of Leisure Re- search, 25, 84-99. Neijndorff (1997) . Een Indo in Holland. Ro tte rdam: Indonet. Oei, I. S., & Schreuder, P. (1995). Handreiking voor hulpverleners. The Hague: Stichting Pelita. Paas, R. (1998). Terpstra’s warme woorden zijn niet gevolgd door daden. de Volkskrant, 15. Pfister, R. E. (1993). Ethnic Identity: A new avenue for understanding leisure and recreation preferences, Chapter 4. In A. W. Ewert, D. J. Chavez, & A. W. Magill (Eds.), Culture, Conflict, and Communica- tion in the Wildland-Urban Interface (pp. 53-68). Boulder: Westview Press. Rijkschroeff, B. R., The, G. T., & Wu, S. M. (1993). De positie van oudere Chinezen en oudere Indische Nederlanders vergeleken. The Hague: Labyrint Public a t ion. Rousseau, J., Denis, M. C., Dube, M., & Beauchesne, M. (1995). L’activité, l’autonomie et le bien-être psychologique des personnes agées (Activity, autonomy and psychological well-being of the eld- erly). Loisir et Société, 18, 93-122. Sarwono, S. W. (1989). Psikol ogi Remaja. Jakarta: Rajawali Pers. Searle, M. S., Mahon, M. J., & Iso-Ahola, S. E. (1995). Enhancing a sense of independence and psychological wellbeing among the eld- erly: A field experiment. Journal of Leisur e Research, 27, 107-124. Siegenthaler, K. L., & Vaughan, J. (1998). Older women in retirement Communities: Perceptions of recreation and leisure. Leisure Sciences, 20, 53-66. doi:10.1080/01490409809512264 Simcox, D. E. (1993). Cultural foundations for leisure preference, be- havior, and environmental orientation, Chapter 19. In A. W. Ewert, D. J. Chavez, & A. W. Magill, (Eds.), Culture, Conflict, and Com- munication in the Wildland-Urban Interface (pp. 267-280). Boulder: Westview Press. Smith, S. L. J. (1990). Dictionary of concepts in recreation and leisure. Westport: Greenwood Press. Soeters, A., de Hoog, K., & te Kloeze, J. W. (1996). Integreren door middel van vrijetijd? Vrijetijdsbesteding en integratie van Turkse gezinnen in een Arnhemse wij k. Vrijetijd Studies, 14, 19-33. Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park: Sage Publications, Inc. Thissen, F. (1992). Activity patterns of the elderly in rural areas in the Netherlands. In A. Kempers-Warmerdam (Ed.), The elderly in rural areas of The Netherlands: Possibilities and limitations (nr. 41) (pp. 31-40). Amsterdam: Institut voor Sociale Geografie, Universiteit van Amsterdam. Tirone, S. (1997). Leisure and centrality of family: Issues of care in the lives of South Asians in Canada. Journal of Leisurability , 24, 23 -32. Anonymous (1997) Tijdsbesteding en vrijetijdsactiviteiten. In J. Timmer- mans, (Ed.), Rapportage ouderen 1996 (pp. 161-174). Rijswijk: So- ciaal en, Cultureel Planbureau. van der Hoeven, H. (1996). Stichting Pelita belicht. The Hague: Sticht- ing Pelita. van der Hoeven, H., & Diederen, H. (1997). Indisch maatschappelijk werk: Werkboek 1-Cliëntprofielen. The Hague: VOG-sectie AMV and Stichting Pelita. van der Hoeven, H., & Diederen, H. (1998). Indisch maatschappelijk werk: Werkboek 2-Pelita-Profiel. The Hague: VOG-sectie AMV and Stichting Pelita. Voges, W. & Pongratz, H. (1988). Retirement and the lifestyles of older women. Ageing and Society, 8, 63-84. doi:10.1017/S0144686X0000653X Vriezen, J. A. (1993). Rijst of aardappelen?: Indische en autochtone ouderen in Nederland. PhD Dissertation, Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam. Wearing, B. (1995). Leisure and resistance in an ageing society. Lei- sure Studies, 14, 263-279. doi:10.1080/02614369500390201 Wilson, N. C., & Russell, D. G. (1994) What’s age got to do with it? Journal of Physical Education New Zealand, 27 , 15-18. Wolters-Nordhoff Atlas Statistiek 97/98. (1997). Groningen: Wolt- ers-Nordhoff b.v. and Rotterdam: Software b.v., on CD-Rom. Yin, R. K. (1994) Case study research: Design and methods. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc. Young, D. R., King, A. C., & Oka, R. K. (1995). Determinants of exer- cise level in the sedentary versus underactive older adult: Implica- tions for physical activity program development. Journal of Aging & Physical Activity, 3, 4-25.