Open Journal of Pediatrics, 2011, 1, 51-63 doi:10.4236/ojped.2011.14014 Published Online December 2011 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ojped/ OJPed ) Published Online December 2011 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/OJPed Feeding problems and GI dysfunction in children with asperger syndrome or pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified; comparison with their siblings Vahe Badalyan, Richard H. Schwartz Department of Gastroenterology, Nutrition and Hepatology CNMC, Washington DC, USA. Email: vbadalyan@gmail.com Received 2 October 2011; revised 13 November 2011; accepted 24 November 2011. ABSTRACT Objective: There are few previously published studies of feeding problems and/or gastrointestinal dysfunc- tion among children with Asperger syndrome (AS) or Pervasive Developmental Disorder (PDD-NOS), com- pared to sibling controls. Study Design: On-line par- ent autism groups 90% from North America. Statis- tical analysis: Chi square and binomial logistic re- gression statistical analysis Results: Completed sur- veys were received for 64 children with AS, 44 with PDD-NOS, total = 108), and 82 normal sibling mat- ches. Children with high-functioning autism had higher likelihood of frequent (>50% of the time) problematic feeding behaviors and gastrointestinal dysfunction, such as unusual food preferences (OR 23.9, 95% CI 7.3 - 78.7), insistence on unusual food presentation (OR 5.8, 95% CI 1.8 - 18.4), and poor mealtime social behavior (OR 16.1, 95% CI 4.1 - 64.1). These children also had higher odds of frequent constipation (OR 8.3, 95% CI 2.2 - 31.9) and fecal incontinence (OR 5.4, 95% CI 1.1 - 27.3). Nine chil- dren in AS/PDD-NOS group (4%) were believed by parent to have celiac disease (3% or 1% had intesti- nal biopsy), compared to 2 in control group. Conclu- sion: 57% of the AS/PDD-NOS group had frequent unusual food preferences vs. 5% of controls. Forty- eight percent of children with AS/PDD-NOS had frequent dislikes of new foods, compared to 6% of controls. For symptoms of specific gastrointestinal dysfunction, children with AS/PDD-NOS had higher prevalence of frequent constipation (30% vs. 4%) and fecal incontinence (22% vs. 2 %). Keywords: Asperger Syndrome; PDD-NOS, Feeding Behaviors; Gastrointestinal Dysfunction; Food Prefer- ences 1. INTRODUCTION An estimated 1 in 110 children in the US and Canada are estimated to have a diagnosis of Autism Spectrum dis- order and these rates have been increasing in the past decade [1]. Autism spectrum disorder (ASD), is a het- erogeneous group of neuro-developmental disorders that the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual IV-R currently subdivides into three subgroups: Asperger syndrome, pervasive developmental disorder-not otherwise speci- fied (PDD-NOS) which is the most common and has the least precise diagnostic criteria [2], and classical autism [3]. Children with PDD-NOS almost universally have impairments in social reciprocity and communication, without significant repetitive and stereotyped behaviors [4]. Compared to classic autism, they have comparably se- vere but more circumscribed social communication dif- ficulties with fewer non-social features such as sensory integration or feeding problems. The current draft guide- lines of the upcoming DSM-V will mandate repetitive and stereotyped behaviors in addition to major defects in language and communication and socialization [4]. Previous publications have documented increased rates of feeding problems and gastrointestinal dysfunc- tion among children with ASD. Although opinions differ, a majority of published studies on the subject of child- hood autism and gastrointestinal problems report higher rates of feeding problems in children with ASD com- pared to controls [5-13]. The Brief Autism Mealtime Behavior Inventory (BAMBI) has been developed to evaluate the mealtime behavior of children with autism [14]. The BAMBI demonstrated good internal consis- tency, high test-re-test reliability. A recent study comparing 48 children (3 to 12 years old) with ASD, to their matched siblings found that the ASD group had a mean of 13 eating problems, with lack of food variety predomination while the sibling group had a mean of 5 eating problems [11]. Feeding problems  V. Badalyan et al. / Open Journal of Pediatrics 1 (2011) 51-63 52 included inflexible food preferences (based on food tex- ture, color, smell, presentation, limited variety diets, and specific utensil requirements), oral-motor dyspraxia and disruptive mealtime behaviors, among others. In a sur- vey of 138 children with autism and 298 typically de- veloping children, Schreck and colleagues (2005), found that children with autism had higher rates of refusing most foods, requiring specific utensils, requiring par- ticular food presentation, accepting only pureed or low textured foods, and eating a narrow variety of foods [15]. Smith et al also found that children with ASD had a limi- ted repertoire of foods (35% vs. 3%) [8]. Emond et al. (2010) found that caregivers of autistic children reported significantly more frequently feeding slow during early infancy, parent having difficulties feeding the child, and the child being a picky eater [16]. In 2011, investigators from the University of Califor- nia reported that 249 children on the autism spectrum had significantly more GI problems (42%) than 163 sib- lings (12%). This study was registry-based and the in- vestigators conducted in-home structured medical his- tory interviews by parent recall. Those children with classic autism had increased odds of having GI problems compared to less severely affected children with ASD [12]. The most common symptoms of GI dysfunction in- clude abdominal pain, dysphagia, gastrointestinal reflux (GER), constipation, withholding stool, and fecal incon- tinence [15]. Constipation rates among the children with autism was higher than control groups in the studies of Melmed [17], Taylor [18], Afzal [19], Molloy [7], and Smith [8]. In contradistinction, analysis of a database of 211,480 children from the United Kingdom found no difference in gastrointestinal complaints in 96 children diagnosed with ASD compared with 449 nested controls [20]. In- vestigators from the Mayo Clinic also found no signi- ficant associations between autism case status and overall incidence of GI dysfunction [21]. An Australian study concluded that children with early gastrointestinal problems were no more likely to be represented in the upper quartile of scores on the Autism Spectrum Quo- tient (AQ) scales [4]. The purpose of this study was to compare the preva- lence of feeding difficulties and gastrointestinal dys- function in children with Asperger syndrome and Perva- sive Developmental Disorder (so-called high-functioning autism) and their typically developing siblings. Our in- tention was to use sibling controls in order to control for the influence of social environment. 2. STUDY DESIGN AND PATIENT POPULATION This was a cross-sectional online survey conducted from February 2009 through April 2009. The lengthy survey instrument included 41 questions pertaining to demo- graphics, family income, developmental milestones, feeding behaviors and odd mannerisms, food preferences, and GI dysfunction at the time when the child was be- tween ages 3 and 12 (see appendix). The survey con- tained two almost identical parts, one for the child with AS or PDD-NOS and one for the typically-developing sibling. Both parts contained the same 41 questions with the exception of the question pertaining to ASD diagno- sis (only available in ASD part). The survey was se- curely posted online at a commercial survey website http://www.formsite.com (Vroman systems Inc, Chicago, IL). At no point was the survey tool sold and no profits were generated from using the survey tool. The authors bore all the costs associated with publishing the survey online. The link to the survey was e-mailed repeatedly to na- tional, regional, state, and large city autism organizations and support groups. Parents were asked to complete the survey if they had a child with AS or PDD-NOS. If a parent had several children with ASD, he/she was asked to complete the survey separately for each ASD child. The survey was confidential and anonymous. The survey link contained an introductory statement about the pur- pose of the survey, voluntary participation, risks and benefits, and contacts of investigators and IRB officer. The drafts of the survey were pre-tested on 10 parents of ASD children from a pediatric practice in Vienna, VA, and reviewed by local specialists in developmental/be- havioral pediatrics, and pediatric gastroenterology. The survey protocol was approved without full formal review by Inova Fairfax Hospital Institutional Review Board. 2.1. Definitions Used for This Study Children were defined as having Asperger syndrome or PDD-NOS if the parents indicated so in the survey and, if the diagnosis was made by a primary care or pediatric sub-specialist physician or psychologist. Definitions used in this study: We categorized the frequencies of feeding behaviors and gastrointestinal problems into “Never”, “Rarely” (less than 10% of the time), “Sometimes” (10% - 50% of the time), and “Of- ten” (more than 50% of the time). “Diarrhea” was defined as passing at least three wa- tery unformed stools in a day. “Constipation” was de- fined as hard or painful stools passed less than three times per week. “Pica” was defined as the ingestion of unusual non- food items such as dirt or string. 2.2. Statistical Methods Data was analyzed using SPSS version 18 (SPSS Inc. C opyright © 2011 SciRes. OJPed  V. Badalyan et al. / Open Journal of Pediatrics 1 (2011) 51-63 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. 53 OJPed Chicago, Illinois). Descriptive statistics (means and standard deviations) were used for continuous variables, and proportions were used for categorical variables. Fischer’s exact test was used to compare dichotomous variables pertaining to feeding and gastrointestinal dys- function between the groups. To control for influences of variables pertaining to age, gender, degree of develop- mental impairment, medical problems, country, food allergies, and dietary restrictions, binomial logistical regression models were created with these variables be- ing included as independent variables, along with the autistic spectrum disorder variable (case vs. control). The variables pertaining to feeding and gastrointestinal dysfunction were included one by one in the regression model as a dependent variable. 3. RESULTS Surveys were completed for 64 children with Asperger Syndrome, 44 children with PDD-NOS (combined total = 108), and 82 of their typically-developing siblings. All participants were between the ages of 3 and 12 years. Males comprised 88% of the combined (AS/PDD-NOS) group and 50% of the control group (p < 0.001). Mean ages at the time of the survey were 7.9 years and 7.7 years in the ASD and control groups, respectively (p = 0.54, NS) (Table 1). U.S. respondents comprised 85% of the ASPDD-NOS group and 78% of the control group (p = 0.25, NS). The highest numbers of U.S. respondents came from Virginia, Kansas, Texas, Indiana, and Missouri. Fifteen percent of completed responses came from Canada. A bare majority (52%) of the parent responders reported that their household income in 2008 exceeded $75,000 per year (p = 0.84, NS). Approximately 5% of the control group was enrolled in Medicaid. Cross-tabulations of children with Asperger syndrome and PDD-NOS showed that the two groups were, in general, similar in terms of most developmental mile- stones, food preferences and gastrointestinal dysfunction (chi square p values >0.05) (Tables 2 and 3). There were some specific developmental milestone differences be- tween children with AS and those with PDD-NOS. The mean age at the time of diagnosis was 4-years for chil- dren with PDD-NOS versus 6.2 years for children with AS (independent samples t-test, p value < 0.001). Sixty- seven percent of PDD-NOS group versus 86% of chil- dren in the AS group were toilet trained by age of 4 (Chi square P value = 0.029). Acquisition of language by the age of 4 years was achieved by 55% of PDD-NOS group and by 88% of Asperger group (Chi-square P value < 0.001) (Table 2). Because of the small number of differences for feed- ing problems or GI dysfunction, children with AS or PDD-NOS were combined into a single combined study group for subsequent analysis. Their typically-develop- ing siblings were also combined into a single control group. There were major differences between children with the combined AS/PDD-NOS and sibling controls in re- portedly having any major developmental problem (AS/ PDD-NOS = 200 [96%] compared to 9 [6%] in control group, p < 0.000, OR = 337.8, CI = 114 - 1000.8), disor- tions or paucity of social play (AS/PDD-NOS = 103 vs controls = 2, p < 0.000, OR = 42.9, CI = 5.3 - 349.9), odd routines (AS/PDD-NOS = 139 vs control group = 3, p < 0.000, OR = 107.4, CI = 31.3 - 369.1), never spoke by age 4 years (AS/PDD-NOS = 40 vs controls = 1, p < 0.000, OR = 42.9, CI = 5.3 - 349.9) (Table 3). The combined AS/PDD-NOS group differed signify- cantly from the control group for frequent disruptive feeding problems. These included obsessional food pre- ferences (i.e. insistence on: a. specific food colors, shapes, or textures, insistence on eating food with spe- cific utensils/dishes, fear of new foods, and disruptive family mealtime behavior, (Ta b l e 4). Unusual food pre- ference (frequency > 50% of time) was present for 127 Table 1. Study participants. Control AS/PDD Combined group Significant n = 82 % n = 108 % Age 7.7 7.9 p = 0.54 St dev 2.8 2.7 Male gender 41 50% 95 88% p < 0.001 Live in USA 64 78% 92 85% p = 0.25 Family income > $75000/year 44 54% 55 51% p = 0.84 Developmental Milestones Spoke by age 4 79 96% 80 74% p < 0.001 Spoon trained by age 3 79 96% 83 77% p < 0.001 Toilet trained by age 4 77 94% 83 77% p < 0.001  V. Badalyan et al. / Open Journal of Pediatrics 1 (2011) 51-63 54 Table 2. Occurrence of select behaviors and GI symptoms that were frequent. GI symptoms Asperger (n = 134) PDD-NOS (n = 71)Combined Asperger and PDD-NOS (n = 6) Controls (n = 160) Chi-Square P value vomiting 12 2 2 5 p = 0.002 % 9.0% 2.8% 33.3% 3.1% diarrhea 10 12 2 4 <0.001 % 7.5% 16.9% 33.3% 2.5% constipation 35 25 2 9 <0.001 % 26.1% 35.2% 33.3% 5.6% soiling 27 21 5 7 <0.001 % 20.1% 29.6% 83.3% 4.4% difficulty swallowing 6 11 2 4 <0.001 % 4.5% 15.5% 33.3% 2.5% reflux 17 10 3 11 p = 0.004 % 12.7% 14.1% 50.0% 6.9% abdominal pain 11 5 2 6 p = 0.02 % 8.2% 7.0% 33.3% 3.8% failure to thrive 31 17 3 10 <0.001 % 23.3% 25.0% 50.0% 6.4% any diet restriction 30 19 3 12 <0.001 22.4% 26.8% 50.0% 7.5% any food allergy 30 18 4 21 <0.002 22.4% 25.4% 66.7% 13.1% Table 3. Deviation from normal developmental milestones. AS/PDD-NOS Controls n = 211 % n = 160 % Fischer’s exact test Logistic regression odds ratio (95% CI) No Social Play 103 49% 2 1% 0.000 53.9 (12.8 - 227.2) Odd Mannerisms 174 82% 4 3% 0.000 159.4 (52.5 - 483.9) Odd Routines 139 66% 3 2% 0.000 107.4 (31.3 - 369.1) Any Major Developmental Problem 200 95% 9 6% 0.000 337.8 (114 - 1000.8) Mental Disability 6 3% 2 1% 0.474 1.3 (0.2 - 8.7) or 60% of the AS/PDD-NOS group vs. 9 or 6% of the control group (p < 0.001, OR = 38.4, CI = 15.4 - 95.8) (Table 4). Disruptive family mealtime behavior was noted for 74 or 35% of the AS/PDD-NOS group vs. 7 or 4% or the control group (p < 0.001, OR = 9.9, CI = 4 - 24.7). The combined AS/PDD-NOS group differed signifi- cantly from the control grou by the prevalence of se- p C opyright © 2011 SciRes. OJPed  V. Badalyan et al. / Open Journal of Pediatrics 1 (2011) 51-63 55 Table 4. Abnormal Feeding behaviors, frequency >50% of the time. Frequent (>50%) occurrence of select behaviors and gastrointestinal symptoms Asperger (n = 134) PDD-NOS (n = 71) Combined Asperger and PDD-NOS (n = 6) Controls (n = 160) Chi-Square P value unusual food preferences 76 47 4 6 <0.001 % 56.7% 66.2% 66.7% 3.8% insistence on using utensils 32 18 2 9 <0.001 % 23.9% 25.4% 33.3% 5.6% dislike of new foods 62 42 5 9 <0.001 % 46.3% 59.2% 83.3% 5.6% fear of new foods 73 50 3 20 <0.001 % 54.5% 70.4% 50.0% 12.5% eating nonfood items (Pica) 12 9 2 2 <0.001 % 9.0% 12.7% 33.3% 1.3% Disruptive family mealtime 41 29 4 7 <0.001 behavior 30.6% 40.8% 66.7% 4.4% Disruptive school mealtime behavior 14 12 3 1 <0.001 % 10.4% 16.9% 50.0% .6% unusual posturing during mealtime 24 9 2 5 <0.001 % 17.9% 12.7% 33.3% 3.1% oral motor problems 11 11 3 4 <0.001 % 8.2% 15.5% 50.0% 2.5% lected symptoms of frequent feediang behavior problems (Tab le 5) and GI dysfunction (Tabl e 6 ). ASD chil- dren often had higher prevalence of (frequency >50% of the time) constipation (30% vs. 4%, p < 0.001, OR = 8.1, CI = 3.5 - 19), soiling (22% vs. 2%, p < 0.001, OR = 6.7, CI = 2.7 - 17), and failure to thrive (22% vs. 7%, p < 0.001, OR = 4.5, CI = 2.1 - 9.4). Higher proportions of ASD children were or had been on a restrictive diet (24%) compared to the controls (9%) (p < 0.006).). Regression models additionally revealed that having been on at least one restrictive diet was associated with increased the odds of constipation (OR = 3.38, CI = 1.14 - 10.04, p = 0.029). There were no significant differences in abdominal pain, reflux, or other gastrointestinal pathology between the two study groups (Table 6). Duration of feeding problems: When ASD or control children exhibited unusual mealtime preferences and behaviors; these mostly were long term (lasted >6 months). 4. DISCUSSION In accord with several previous studies, our study re- veals important new information about the high preva- lence, frequency and duration of feeding problems, mealtime misbehaviors, and GI dysfunction in children with Asperger syndrome and PDD-NOS (ASD). The study design addresses and cures some of the criticism of previous published studies of gastrointestinal dys- function in children with autism. This manuscript con- tains information only about AS and PDD-NOS and ex- cludes the large category of classic autism. Parents of children with ASD are often accurate in diagnosing au- tism based on Internet-implemented parent report [22]. We accepted only children who had diagnostic criteria for AS or PDD-NOS outlined by the DSM-IV-R manual. We excluded from analysis all survey responses in which the diagnosis of AS or PDD-NOS was not made by pro- fessionals (see Survey instrument in appendix). We did not obtain verification of the diagnosis of AS or PDD- NOS by independent review of the child’s medical re- cords or by administration of standardized diagnostic tests for AS or PDD-NOS. Is the diagnosis of AS or PDD-NOS accurate? Should the diagnosis for a substantial percentage of participants with ASD be erroneous, we are at a loss to account for C opyright © 2011 SciRes. OJPed  V. Badalyan et al. / Open Journal of Pediatrics 1 (2011) 51-63 56 Table 5. Frequent feeding/behavior problems during meals. Children with ASDControls Feeding Problems/Behavior n = 211 % n = 160% Fischer’s exact test Logistic regression odds ratio (95% CI) P Unusual food preferences 127 60% 6 4% 0.000 38.4 (15.4 - 95.8) 0.000 Dislike of new foods 109 52% 9 6% 0.000 22.2 (9.4 - 52.8) 0.000 Fear of new foods 126 60% 20 13% 0.000 11.3 (6.1 - 21) 0.000 Eating non-food items (Pica) 23 11% 2 1% 0.000 19 (2.4 - 152) 0.006 Disruptive family meal-time 74 35% 7 4% 0.000 9.9 (4 - 24.7) 0.000 behaviors Unusual posturing & meals 35 17% 5 3% 0.000 7.8 (2.5 - 23.7) 0.000 Oral-motor problems 25 12% 4 3% 0.001 5.7 (1.5 - 21) 0.009 Table 6. Frequent occurrence (<50% of time) of GI dysfunction. Children with ASDControls Gastrointestinal Symptom n = 211 % n = 160% Fischer’s exact test Logistic regression odds ratio (95 % CI) P Constipation 62 29% 9 6% 0.000 8.1 (3.5 - 19) 0.000 Soiling 53 25% 7 4% 0.000 6.7 (2.7 - 17) 0.000 Vomiting 16 8% 5 3% 0.073 1.9 (0.5 - 6.9) 0.305 Diarrhea 24 11% 4 3% 0.001 3.9 (1 - 14.8) 0.043 Abdominal Pain 18 9% 6 4% 0.087 2 (0.7 - 6.3) 0.220 Failure To Thrive 51 24% 10 6% 0.000 4.5 (2.1 - 9.4) 0.000 Any Diet Restriction 52 25% 12 8% 0.000 3.1 (1.4 - 7.1) 0.006 Any Food Allergy 52 25% 21 13% 0.006 2.4 (1.2 - 4.5) 0.009 Celiac Disease 9 4% 2 1% 0.703 2.1 (0.2-19) the large differences between subjects and sibling con- trols in gender ratio, achievement of developmental mi- lestones, feeding problems, and gastrointestinal com- plaints. Strengths of this survey study include: 1) posting the survey on line in a parallel, split-screed format with questions about children 3 - 12-years old with AS or PDD-NOS on the left side of the split screen, and ques- tions relating to the sibling control on the right side; 2) the wide geographic distribution (no state contributed more than 30% of the U.S. total) and responses from a large number of small towns and cities; 3) Canadian participation; 4) sibling controls; 5) specific develop- mental and social milestones, and data collection detail- ing frequency and duration of mealtime feeding prob- lems and GI dysfunction. Self-criticism of survey methodology: We excluded parents who are not members of ASD support groups. We admittedly captured respondents who express strong opinions on the subject, respondents with high socio- economic status, and those who are computer literate. This age range (3 - 12-year old) was selected because based on our assumptions that: 1) high-functioning au- tism is infrequently diagnosed before the age of 3, 2) feeding patterns and behaviors of children frequently mature after age three years and tend to remain relatively stable until adolescence, 3) eating patterns of children over 12-years are difficult to monitor due to significant amount of time spent outside home. The survey instrument was developed based on our review of the literature and our own clinical experiences, as well as using comments and suggestions from parents and developmental pediatricians. We did not undertake formal testing of the survey instrument to assess its con- struct validity and reliability. The mean age of diagnosis of children with PDD- NOS (4.4 years), was significantly younger than the mean age at diagnosis of the Asperger Syndrome group C opyright © 2011 SciRes. OJPed  V. Badalyan et al. / Open Journal of Pediatrics 1 (2011) 51-63 57 (7.7 years). This may not be a weakness of the study. Children with PDD-NOS have many more deficits in language and communication and the delay in language acquisition attracts the attention of parent, extended family, and physician. The diagnosis of Asperger Syn- drome is usually made later than that of PDD-NOS be- cause language delay is not so severe. We did not include a formal standardized diagnostic test for Asperger syndrome to keep the time to complete the questionnaire relatively short. In agreement with results of our study, Olmstead County children with ASD were more likely to manifest feeding issues, food selectivity and constipation [21]. In that study, as in ours, there was no evidence of an in- crease in celiac disease in ASD children compared to the control group. There are no data, however, to ascertain whether the study group in the Olmstead county Minne- sota, study had acute, chronic, or some combination of GI dysfunction [21]. We also do not know about the spe- cifics of “strange feeding issues and/or food selectivity” in that study. In our survey, more than 52 children (25%) in the AS/PDD-NOS group had been on (or currently are on) restricted diets, most often, casein-free or gluten-free, (p < 0.001) compared to the sibling control group (OR = 3.1, CI = 1.4 - 7.1). Only 1% of those children on a glu- ten-free diet had a biopsy-proven diagnosis of celiac disease. A multidisciplinary panel of experts recently reviewed the medical literature on the diagnostic evalua- tion and management of GI problems in children with ASD [23]. Statement 12 of their consensus notes: “avail- able research data do not support the use of a casein-free diet, a gluten-free diet, or combined gluten-free, casein- free (GFCF) diet as a primary treatment for individuals with ASDs.” 5. CONCLUSIONS In a North American on-line survey of many parent support groups for ASD children, children age 3 - 12 years with Asperger syndrome and PDD-NOS have a higher prevalence of abnormal feeding behaviors and gastrointestinal dysfunction compared to their non-ASD siblings. Asperger and PDD-NOS groups were similar in the number and frequency and duration of feeding prob- lems, disruptive mealtime misbehavior, and GI dysfunc- tion. REFERENCES [1] Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network Surveillance Year 2006 Principal Investigators, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorders (2006) Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), United States, 18 December, 2009/58(SS10), 1-20. [2] Mandy, W., Charman, T., Gilmour, J. and Skuse, D. (2011). Toward specifying pervasive developmental dis- order—Not otherwise specified. Autism Research, 4, 121-131. doi:10.1002/aur.178 [3] American Psychiatric Association (2000) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th Edition, American Psychiatric Association, Washington DC. [4] Whitehouse, A.J., Mayberry, M., Wray, J.A. and Hickey, M. (2011) No association between early gastrointestinal problems and autistic-like traits in the general population. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 53, 457- 462. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2011.03915.x [5] Martins, Y., Young, R.L. and Robson, D.C. (2008) Feed- ing and eating behaviors in children with autism and typically developing children. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorder s, 38, 1878-1887. doi:10.1007/s10803-008-0583-5 [6] Matson, J.L., Fodstad, J.C. and Dempsey, T. (2009) The relationship of children’s feeding problems to core symptoms of autism and PDD-NOS. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 3,759-766. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2009.02.005 [7] Molloy, C.A. and Manning-Courtney, P. (2003) Preva- lence of chronic gastrointestinal symptoms in children with autism and autistic spectrum disorders. Autism, 7, 165-171. doi:10.1177/1362361303007002004 [8] Smith, R.A., Farnworth, H., Wright, B. and Allgar, V. (2009) Are there more bowel symptoms in children with autism compared to normal children and children with other developmental and neurological disorders? A case control study. Autism, 13, 343-355. doi:10.1177/1362361309106418 [9] Schreck, K.A., Williams, K. and Smith, A.F. (2004) A comparison of eating behaviors between children with and without autism. Journal of Autism and Develop- mental Disorders, 34, 433-438. doi:10.1023/B:JADD.0000037419.78531.86 [10] Kodak, T. and Piazza, C.C. (2008) Assessment and be- havioral treatment of feeding and sleeping disorders in children with autism spectrum disorders. Child & Ado- lescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 17 , 887- 890. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2008.06.005 [11] Nadon, G., Feldman, D.E., Dunn, W. and Gisel, E. (2011) Mealtime problems in children with autism spectrum disorder and their typically developing siblings: A com- parison study. Autism, 15, 98-113. doi:10.1177/1362361309348943 [12] Wang, L.W., Tancredi, D.J. and Thomas, D.W. (2011) The prevalence of gastrointestinal problems in children across the United States with autism spectrum disorders from families with multiple affected members. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 32, 351-360. doi:10.1097/DBP.0b013e31821bd06a [13] Provost, B., Crowe, T.K., Osbourn, P.L., McClain, C. and Skipper, B.J. (2010) Mealtime behaviors of preschool children: Comparison of children with autism spectrum disorder and children with typical development. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics, 30, 220-233. doi:10.3109/01942631003757669 [14] Lukens, C.T. and Linsheid, T.R. (2008) Development and validation of an inventory to assess mealtime behavior C opyright © 2011 SciRes. OJPed  V. Badalyan et al. / Open Journal of Pediatrics 1 (2011) 51-63 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. 58 OJPed problems in children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorder s, 38, 342-352. doi:10.1007/s10803-007-0401-5 [15] Schreck, K.A. and Williams, K. (2006) Food preferences and factors influencing food selectivity for children with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 27, 353-363. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2005.03.005 [16] Emond, A., Emmett, P., Steer, C. and Golding, J. (2010) Feeding symptoms, dietary patterns, and growth in young children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics, 126, e337-e342. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-2391 [17] Melmed, R.D., Schneider, C.K. and Fabes, R.A. (2000) Metabolic markers and gastrointestinal symptoms in children with autism and related disorders. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, 31, S31-32. [18] Taylor, B., Miller, E., Lingam,R., Andrews, N., Simmons, A. and Stowe, J. (2002) Measles, mumps, and rubella vaccination and bowel problems or developmental re- gression in children with autism: Population study. Brit- ish Medical Journal (BMJ), 324, 393-396. doi:10.1136/bmj.324.7334.393 [19] Afzal, N., Murch, S., Thirrupathy, K., et al. (2003) Con- stipation with acquired megarectum in children with au- tism. Pediatrics, 11 2, 939-942. doi:10.1542/peds.112.4.939 [20] Black, C., Kaye, J.A. and Jick, H. (2002) Relation of childhood gastrointestinal disorders to autism: Nested case-control study using data from the UK General Prac- tice Research Database. British Medical Journal (BMJ), 325, 419-421. doi:10.1136/bmj.325.7361.419 [21] Ibrahim, S.H., Voigt, R.G., Katusic, S.K., et al. (2009) Incidence of gastrointestinal symptoms in children with autism: A population-based study. Pediatrics, 124, 680- 686. doi:10.1542/peds.2008-2933 [22] Lee, H., Marvin, A.R., Watson, T., et al . (2010) Accuracy of phenotyping of autistic children based on Internet im- plemented parent report. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics, 153B, 1119-1126. [23] Buie, T., Campbell, D.B., Fuchs, G.J., Furuta, G.T., Levy, J., Van de Water, J., et al. (2010) Evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment of gastrointestinal disorders in indiviuals with ASDs: A consensus report. Pediatrics, 125, S1-S18. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-1878C  V. Badalyan et al. / Open Journal of Pediatrics 1 (2011) 51-63 59 APPENDIX SURVEY INSTRUMENT **SURVEY OF FEEDING AND OTHER DIGESTIVE PROBLEMS IN CHILDREN WIT H AUTISM SPECTRUM DISORDERS By filling out the following survey, you can help pediatricians and other health professionals learn more about certain problems in children with autism spectrum disorders (ASDs). Such problems include unusual food preferences; aver- sion to certain food colors, textures, and types; ingestion of non-food items; very restricted choices of foods; special diets; sensory processing disorders; oral-motor swallowing problems; vomiting, diarrhea, or constipation; and symp- toms of gastroesophageal reflux (GERD) and its complications, such as erosive esophagitis, and food allergies. Questions in Column “A” pertain to your child with ASD when he/she was ages 3 - 12 years, even if he/she is older now. In Column “B”, we ask the same questions for a sibling of your ASD child, closest to him/her in age. Please check the applicable box below and follow the instructions. I have at least one child with ASD and at least one child who is ASD-free Complete both columns “A” and “B” I have at least one child with ASD, and no children who are ASD-free Complete column “A” only I have no children with ASD, and at least one child who is ASD-free Complete column “B” only Please FILL IN the blanks or CHECK the best choice of the following questions: Column A Child with Autistm Spectrum Disorder Column B Child without Autism Spectrum Disorder (control child) Please provide the last 4 digits of your phone number for tracking purposes. ___ ___ ___ ___ ___ ___ ___ ___ City and state of your home Current age and gender of your child ____years Male Female ____years Male Female What is your child’s diagnosis? (Please check all that apply) Autism Pervasive developmental disorder, NOS Sensory integration disorder Asperger syndrome Static encephalopathy Other (please specify) _______ Child without Autistic Spectrum Disorder Proceed to the next question Age at the time of diagnosis _____________ years Child without Autistic Spectrum Disorder Proceed to the next question Was the diagnosis made by a child neurologist, child psychiatrist, psy- chologist, general pediatrician, family physician, or developmental pediatric- cian? Yes No (who diagnosed your child? ____________ ) Uncertain Child without Autistic Spectrum Disorder Proceed to the next question Check all that apply to your child Met developmental milestones Speaking and understanding appropriately by 4 years of age. Never spoke fluently Difficulty with sustained meaningful interactive play with same-age child by the age of 4 years Unusual mannerisms or demanding same rou- tine over and over a. Met developmental milestones b. Speaking and understanding appropriately by 4 years of age. c. Never spoke fluently d. Difficulty with sustained meaningful interac- tive play with same-age child by the age of 4 years e. Unusual mannerisms or demanding same routine over and over Does (did) your child have any of the following neurological/developmental/ genetic conditions? (Please check all that apply) Seizures Down syndrome Hearing disability Mental retardation Other (please specify) _________ Not applicable Seizures Down syndrome Hearing disability Mental retardation Other (please specify) _________ Not applicable C opyright © 2011 SciRes. OJPed  V. Badalyan et al. / Open Journal of Pediatrics 1 (2011) 51-63 60 Does (did) your child have any other medical conditions? Yes (please specify ____________________) No Uncertain a. Yes (please specify ____________________) b. No c. Uncertain At what age did your child learn to use spoon/fork? ___ years not yet using spoon / fork ___ years not yet using spoon / fork Restricted diet at ages 3 - 12 years? (Please check all that apply) a. Gluten-free b. Soy-free c. Dairy (casein)- free d. Carbohydrate diet e. Candida diet f. Feingold diet g. Rotation diet h. No i. Uncertain a. Gluten-free b. Soy-free c. Dairy (casein)- free d. Carbohydrate diet e. Candida diet f. Feingold diet g. Rotation diet h. No i. Uncertain Duration of typical dinnertime with family at ages 3 - 12 years? a. ≤30 minutes b. 31 - 45 minutes c. 46 - 60 minutes d. 61 - 90 minutes e. >90 minutes a. ≤30 minutes b. 31 - 45 minutes c. 46 - 60 minutes d. 61 - 90 minutes e. >90 minutes Marked preference for specific food colors, shapes, textures, presentation, or specific arrangement of food on the plate at ages 3 - 12 years? (please answer both Frequency and Duration headings) Frequency a. Never b. Rarely (<10%) c. Sometimes (10% - 49%) d. Often (>50%) e. Uncertain Duration a. Never b. <6 months c. 6 mo - 1 year d. >1 year e. Uncertain Frequency a. Never b. Rarely (<10%) c. Sometimes (10% - 49%) d. Often (>50%) e. Uncertain Duration a. Never b. <6 months c. 6 mo- 1 year d. >1 year e. Uncertain Insistence on eating with specific uten- sils/dishes at ages 3 - 12 years? (please answer both Frequency and Duration headings) Frequency a. Never b. Rarely (<10%) c. Sometimes (10% - 49%) d. Often (>50%) e. Uncertain Duration a. Never b. <6 months c. 6 mo - 1 year d. >1 year e. Uncertain Frequency a. Never b. Rarely (<10%) c. Sometimes (10% - 49%) d. Often (>50%) e. Uncertain Duration a. Never b. <6 months c. 6 mo -1 year d. >1 year e. Uncertain Marked aversion/fear of specific food colors, shapes, textures, presentation, or specific arrangement of food on the plate at ages 3 - 12 years? (please answer both Frequency and Duration headings) Frequency a. Never b. Rarely (<10%) c. Sometimes (10% - 49%) d. Often (>50%) e. Uncertain Duration a. Never b. <6 months c. 6 mo -1 year d. >1 year e. Uncertain Frequency a. Never b. Rarely (<10%) c. Sometimes (10 - 49%) d. Often (>50%) e. Uncertain Duration a. Never b. <6 months c. 6 mo -1 year d. >1 year e. Uncertain Fear of ingestion of new foods at ages 3 - 12 years? (please answer both Frequency and Duration headin g s) Frequency a. Never b. Rarely (<10%) c. Sometimes (10% - 49%) d. Often (>50%) e. Uncertain Duration a. Never b. <6 months c. 6 mo -1 year d. >1 year e. Uncertain Frequency a. Never b. Rarely (<10%) c. Sometimes (10% - 49%) d. Often (>50%) e. Uncertain Duration a. Never b. <6 months c. 6 mo -1 year d. >1 year e. Uncertain Ingestion of non-food items, such as paper, string, dirt, hair, at ages 3 - 12 years? (please answer both Frequency and Duration headings) Frequency a. Never b. Rarely (<10%) c. Sometimes (10% - 49%) d. Often (>50%) e. Uncertain Duration a. Never b. <6 months c. 6 mo – 1 year d. >1 year e. Uncertain Frequency a. Never b. Rarely (<10%) c. Sometimes (10% - 49%) d. Often (>50%) e. Uncertain Duration a. Never b. <6 months c. 6 mo - 1 year d. >1 year e. Uncertain Poor social mealtime behaviors (would not sit with family, temper tantrum during meal time, throwing food) at ages 3 - 12 years? (please answer both Frequency and Duration headings) Frequency a. Never b. Rarely (<10%) c. Sometimes (10% - 49%) d. Often (>50%) e. Uncertain Duration a. Never b. <6 months c. 6 mo - 1 year d. >1 year e. Uncertain Frequency a. Never b. Rarely (<10%) c. Sometimes (10% - 49%) d. Often (>50%) e. Uncertain Duration a. Never b. <6 months c. 6 mo – 1 year d. >1 year e. Uncertain C opyright © 2011 SciRes. OJPed  V. Badalyan et al. / Open Journal of Pediatrics 1 (2011) 51-63 61 Behavior outbursts during school lunch, requiring intervention by the teacher or other school personnel at ages 3 - 12 years? (please answer both Frequency and Duration headings) Frequency a. Never b. Rarely (<10%) c. Sometimes (10% - 49%) d. Often (>50%) e. Uncertain Duration a. Never b. <6 months c. 6 mo – 1 year d. >1 year e. Uncertain Frequency a. Never b. Rarely (<10%) c. Sometimes (10% - 49%) d. Often (>50%) e. Uncertain Duration a. Never b. <6 months c. 6 mo -1 year d. >1 year e. Uncertain Eating at the same table with other children who do not have behavioral problems? (please answer both Fre- quency and Duration headings) Frequency a. Never b. Rarely (<10%) c. Sometimes (10% - 49%) d. Often (>50%) e. Uncertain Duration a. Never b. <6 months c. 6 mo -1 year d. >1 year e. Uncertain Frequency a. Never b. Rarely (<10%) c. Sometimes (10% - 49%) d. Often (>50%) e. Uncertain Duration a. Never b. <6 months c. 6 mo -1 year d. >1 year e. Uncertain Unusual posturing (neck or trunk turn- ing/bending/arching) during or after meals at ages 3 - 12 years? (please answer both Frequency and Duration headings) Frequency a. Never b. Rarely (<10%) c. Sometimes (10% - 49%) d. Often (>50%) e. Uncertain Duration a. Never b. <6 months c. 6 mo – 1 year d. >1 year e. Uncertain Frequency a. Never b. Rarely (<10%) c. Sometimes (10% - 49%) d. Often (>50%) e. Uncertain Duration a. Never b. <6 months c. 6 mo -1 year d. >1 year e. Uncertain Oral-motor coordination problems (dif- culty moving solid food inside mouth) at ages 3 - 12 years? (please answer both Frequency and Duration head- ings) Frequency a. Never b. Rarely (<10%) c. Sometimes (10% - 49%) d. Often (>50%) e. Uncertain Duration a. Never b. <6 months c. 6 mo - 1 year d. >1 year e. Uncertain Frequency a. Never b. Rarely (<10%) c. Sometimes (10% - 49%) d. Often (>50%) e. Uncertain Duration a. Never b. <6 months c. 6 mo - 1 year d. >1 year e. Uncertain At what age did your child get toilet training for daytime bowel move- ments? ___ years not yet toilet trained ___ years not yet toilet trained Vomiting at ages 3 - 12 years? (please answer both Frequency and Duration headings) Frequency a. Never b. Rarely (<10%) c. Sometimes (10% - 49%) d. Often (>50%) e. Uncertain Duration a. Never b. <6 months c. 6 mo - 1 year d. >1 year e. Uncertain Frequency a. Never b. Rarely (<10%) c. Sometimes (10% - 49%) d. Often (>50%) e. Uncertain Duration a. Never b. <6 months c. 6 mo - 1 year d. >1 year e. Uncertain Diarrhea (more than 3 watery bowel movements per day) at ages 3 - 12 years? (please answer both Frequency and Duration headings) Frequency a. Never b. Rarely (<10%) c. Sometimes (10% - 49%) d. Often (>50%) e. Uncertain Duration a. Never b. <6 months c. 6 mo - 1 year d. >1 year e. Uncertain Frequency a. Never b. Rarely (<10%) c. Sometimes (10% - 49%) d. Often (>50%) e. Uncertain Duration a. Never b. <6 months c. 6 mo - 1 year d. >1 year e. Uncertain Constipation (more than 3 days be- tween bowel movements) at ages 3 - 12 years? (please answer both Fre- quency and Duration headings) Frequency a. Never b. Rarely (<10%) c. Sometimes (10% - 49%) d. Often (>50%) e. Uncertain Duration a. Never b. <6 months c. 6 mo - 1 year d. >1 year e. Uncertain Frequency a. Never b. Rarely (<10%) c. Sometimes (10% - 49%) d. Often (>50%) e. Uncertain Duration a. Never b. <6 months c. 6 mo - 1 year d. >1 year e. Uncertain Soiling in underpants or withholding stool? (please answer both Frequency and Duration headings) Frequency a. Never b. Rarely (<10%) c. Sometimes (10% - 49%) d. Often (>50%) e. Uncertain Duration a. Never b. <6 months c. 6 mo - 1 year d. >1 year e. Uncertain Frequency a. Never b. Rarely (<10%) c. Sometimes (10% - 49%) d. Often (>50%) e. Uncertain Duration a. Never b. <6 months c. 6 mo - 1 year d. >1 year e. Uncertain C opyright © 2011 SciRes. OJPed  V. Badalyan et al. / Open Journal of Pediatrics 1 (2011) 51-63 62 Inadequate/under weight or failure to thrive at ages 3 - 12 years? a. Yes b. No c. Uncertain a. Yes b. No c. Uncertain Difficulty swallowing solid food at ages 3 - 12 years? (please answer both Frequency and Duration headings) Frequency a. Never b. Rarely (<10%) c. Sometimes (10% - 49%) d. Often (>50%) e. Uncertain Duration a. Never b. <6 months c. 6 mo - 1 year d. >1 year e. Uncertain Frequency a. Never b. Rarely (<10%) c. Sometimes (10% - 49%) d. Often (>50%) e. Uncertain Duration a. Never b. <6 months c. 6 mo - 1 year d. >1 year e. Uncertain Reflux / indigestion/ GERD/ esophagi- tis at ages 3-12 years? (please answer both Frequency and Duration head- ings) Frequency a. Never b. Rarely (<10%) c. Sometimes (10% - 49%) d. Often (>50%) e. Uncertain Duration a. Never b. <6 months c. 6 mo - 1 year d. >1 year e. Uncertain Frequency a. Never b. Rarely (<10%) c. Sometimes (10% - 49%) d. Often (>50%) e. Uncertain Duration a. Never b. <6 months c. 6 mo - 1 year d. >1 year e. Uncertain If you selected “b”, “c”, or “d” in the previous question, what tests did your child have a test to confirm Reflux/ indigestion/ GERD/ esophagitis at the age of 3 - 12 years? (please check all that apply) a. Barium swallow b. pH probe c. Endoscopy d. Biopsy e. Videofluoroscopy f. Other ______ g. No tests h. Not applicabl. i. Uncertain a. Barium swallow b. pH probe c. Endoscopy d. Biopsy e. Videofluoroscopy f. Other _________ g. No tests h. Not applicabl. i. Uncertain Food allergies at ages 3 - 12 years? (please check all that appl y) a. Milk b. Eggs c. Citrus d. Wheat f. Yeast g. Corn h. Other ______ i. No allergies j. Uncertain a. Milk b. Eggs c. Citrus d. Wheat f. Yeast g. Corn h. Other ______ i. No allergies j. Uncertain Abdominal pain requiring a doctor visit at ages 3 - 12 years? (please an- swer both Frequency and Duration headings) Frequency a. Never b. Rarely (<10%) c. Sometimes (10% - 49%) d. Often (>50%) e. Uncertain Duration a. Never b. <6 months c. 6 mo - 1 year d. >1 year e. Uncertain Frequency a. Never b. Rarely (<10%) c. Sometimes (10% - 49%) d. Often (>50%) e. Uncertain Duration a. Never b. <6 months c. 6 mo - 1 year d. >1 year e. Uncertain Celiac disease, proven by blood tests or by intestinal biopsy at ages 3 - 12 years? a. Yes b. No c. Uncertain a. Yes b. No c. Uncertain Eosinophilic esophagitis proven by biopsy at ages 3 - 12 years? a. Yes b. No c. Uncertain a. Yes b. No c. Uncertain Diseases of small or large intestine at ages 3 - 12 years? a. Yes b. No c. Uncertain a. Yes b. No c. Uncertain Medications for gastrointestinal prob- lems that your child took for at least 1 month at ages 3 - 12 years (check all that apply) a. Zantac b. Pepcid c. Prevacid d. Prilosec e. Flagyl f. Laxatives (e.g. Miralax, Milk of Magnesia, etc.) g. Other _________________________ h. Not applicable a. Zantac b. Pepcid c. Prevacid d. Prilosec e. Flagyl f. Laxatives (e.g. Miralax, Milk of Magnesia, etc.) g. Other _________________________ h. Not applicable Who did your child see for his/her gastrointestinal problems at ages 3 - 12 years? (check all that apply) a. Gastroenterologist b. Dietician c. Nutritionist d. Homeopathic practitioner e. Integrative medicine specialist f. Herbalist g. Other (please specify): ______________________ a. Gastroenterologist b. Dietician c. Nutritionist d. homeopathic practitioner e. integrative medicine specialist f. herbalist g. Other (please specify): _____________________ C opyright © 2011 SciRes. OJPed  V. Badalyan et al. / Open Journal of Pediatrics 1 (2011) 51-63 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. 63 OJPed Is your child on Medicaid? yes no yes no Estimate the total out-of-pocket (medi- cal, drug, education, P.T., O.T., and speech therapy) expenditures in the year 20012 for your ASD child. a. Less than $1000 b. $1000 - $5000 c. $6000 - $10,000 d. $11,000 - $25,000 e. >$25,000 a. Less than $1000 b. $1000 - $5000 c. $6000 - $10,000 d. $11,000 - $25,000 e. >$25,000 What is your total household income? a. Less than $25,000 b. $25,000 - $50,000 c. $50,000 - $75,000 d. > $75,000 a. Less than $25,000 b. $25,000 - $50,000 c. $50,000 - $75,000 d. > $75,000 THANK YOU VERY MUCH FOR YOUR TIME AND EFFORT. If you would like to receive a summary of these survey results, please write in your e-mail address ___________________________________.

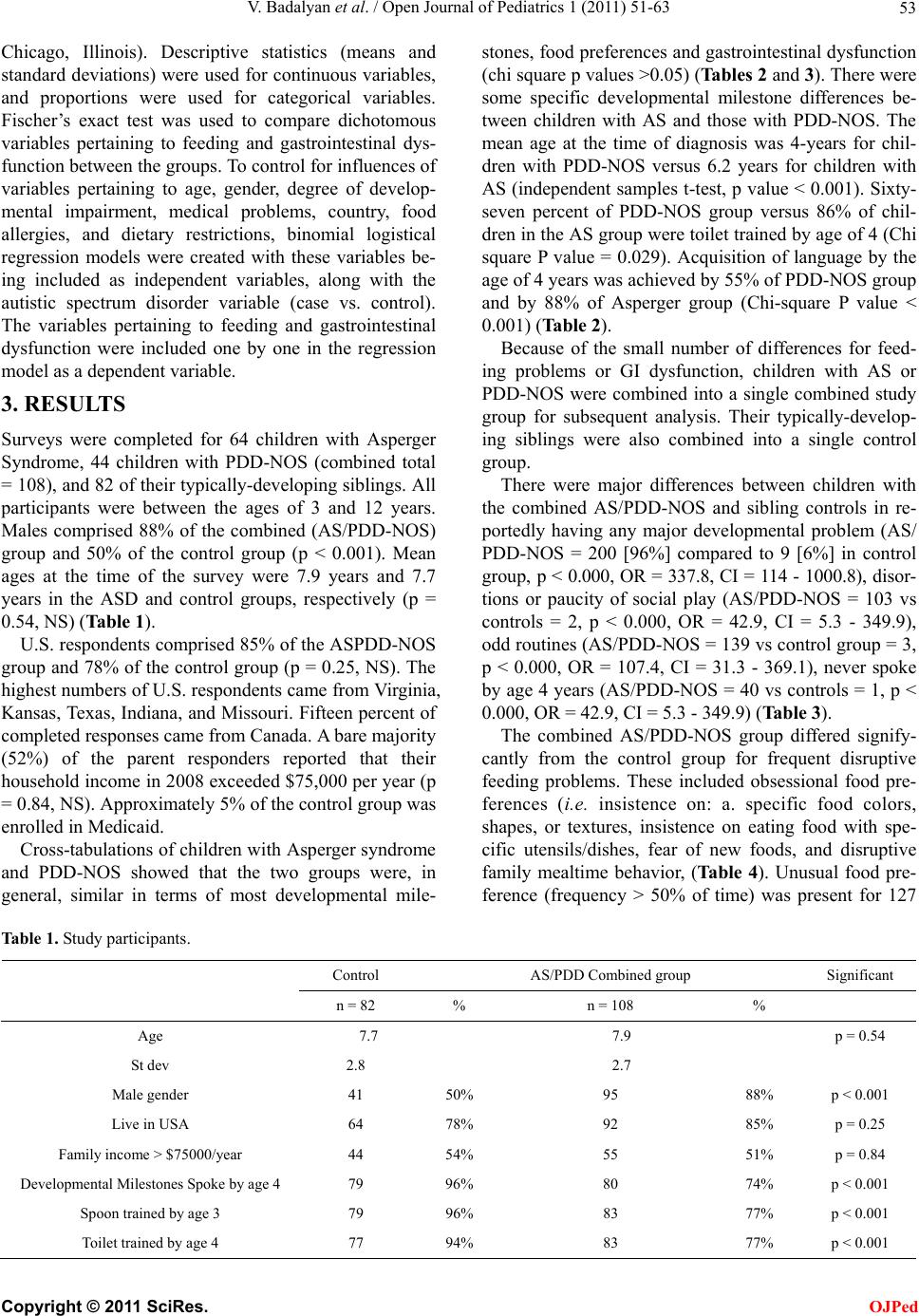

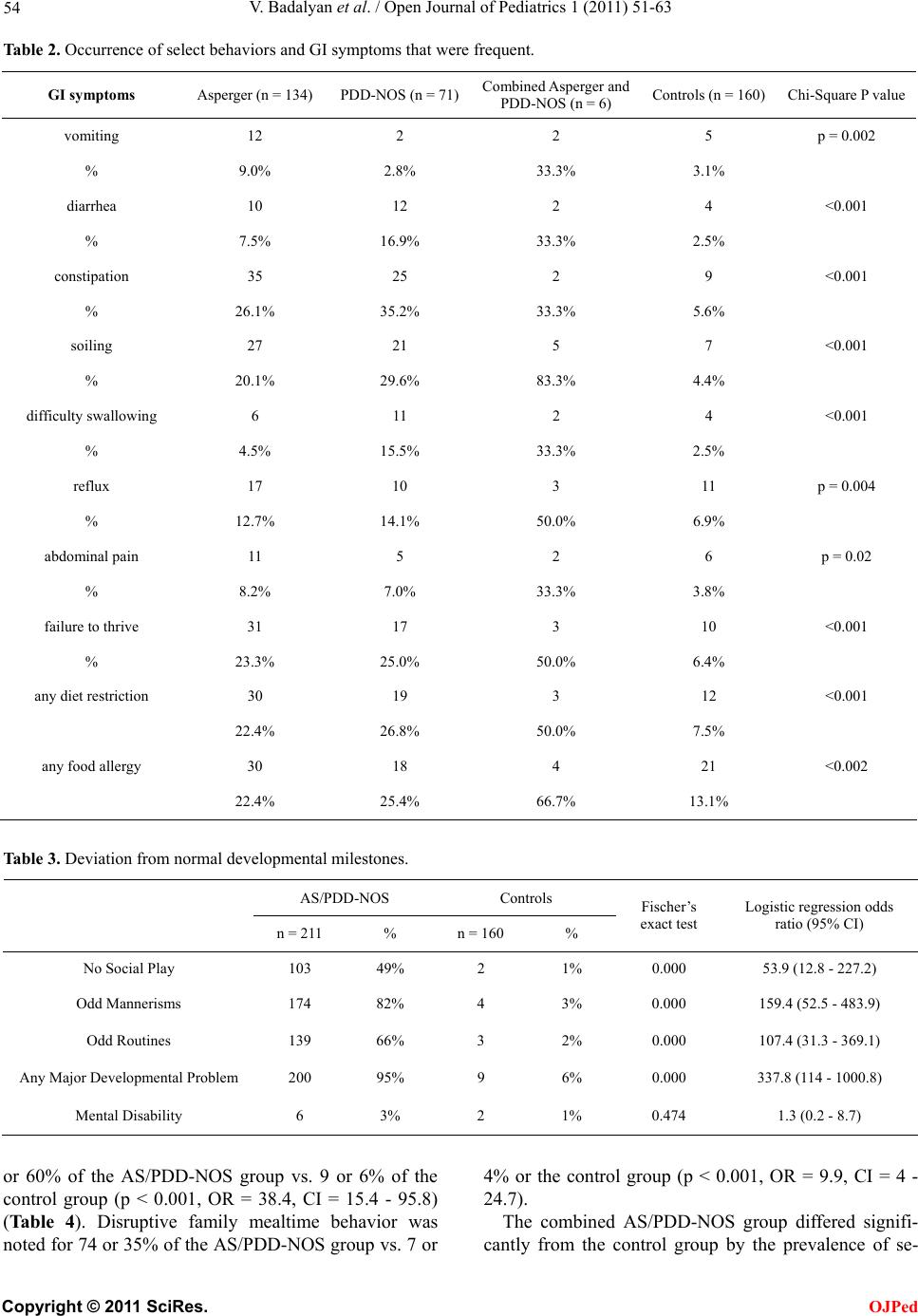

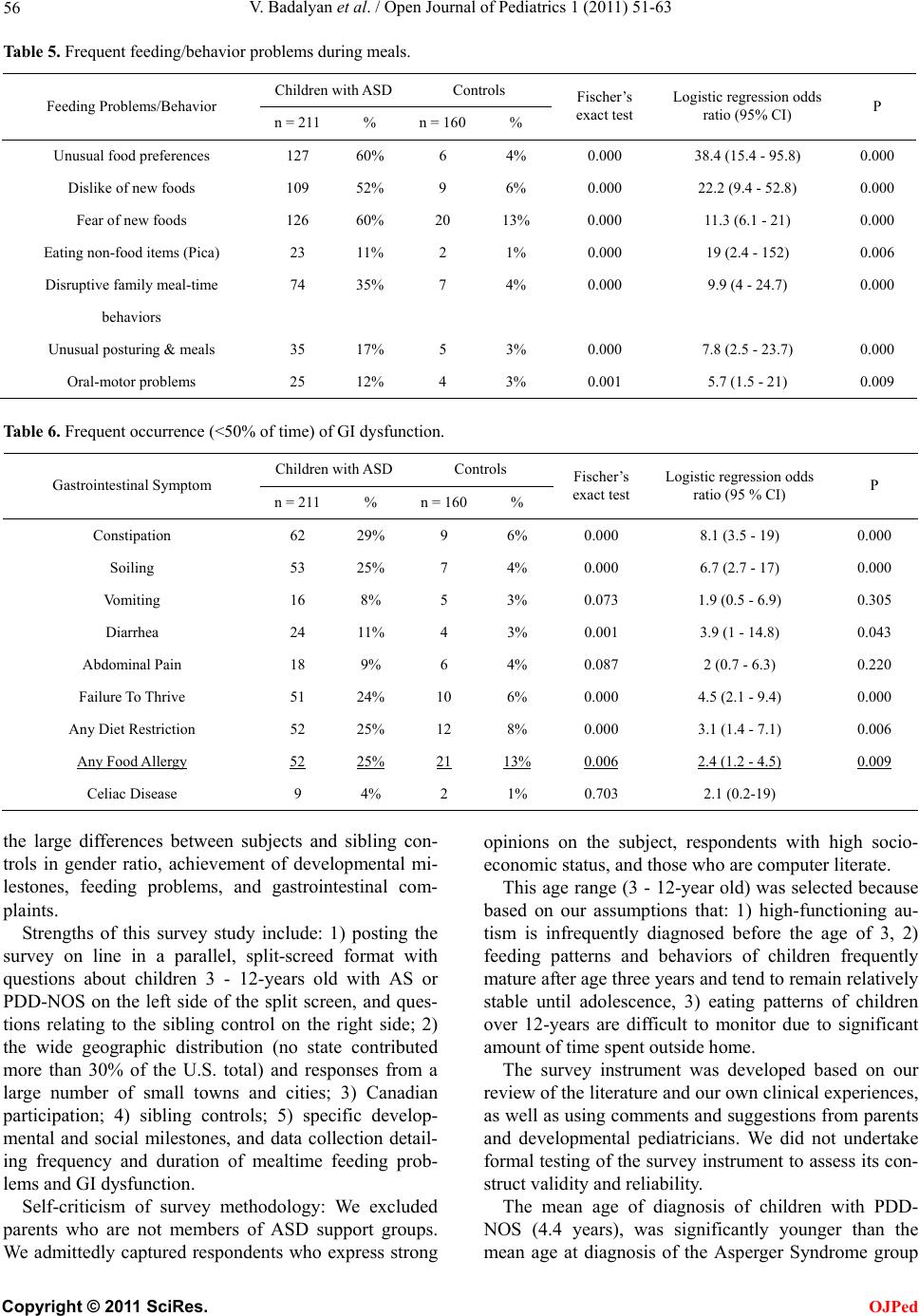

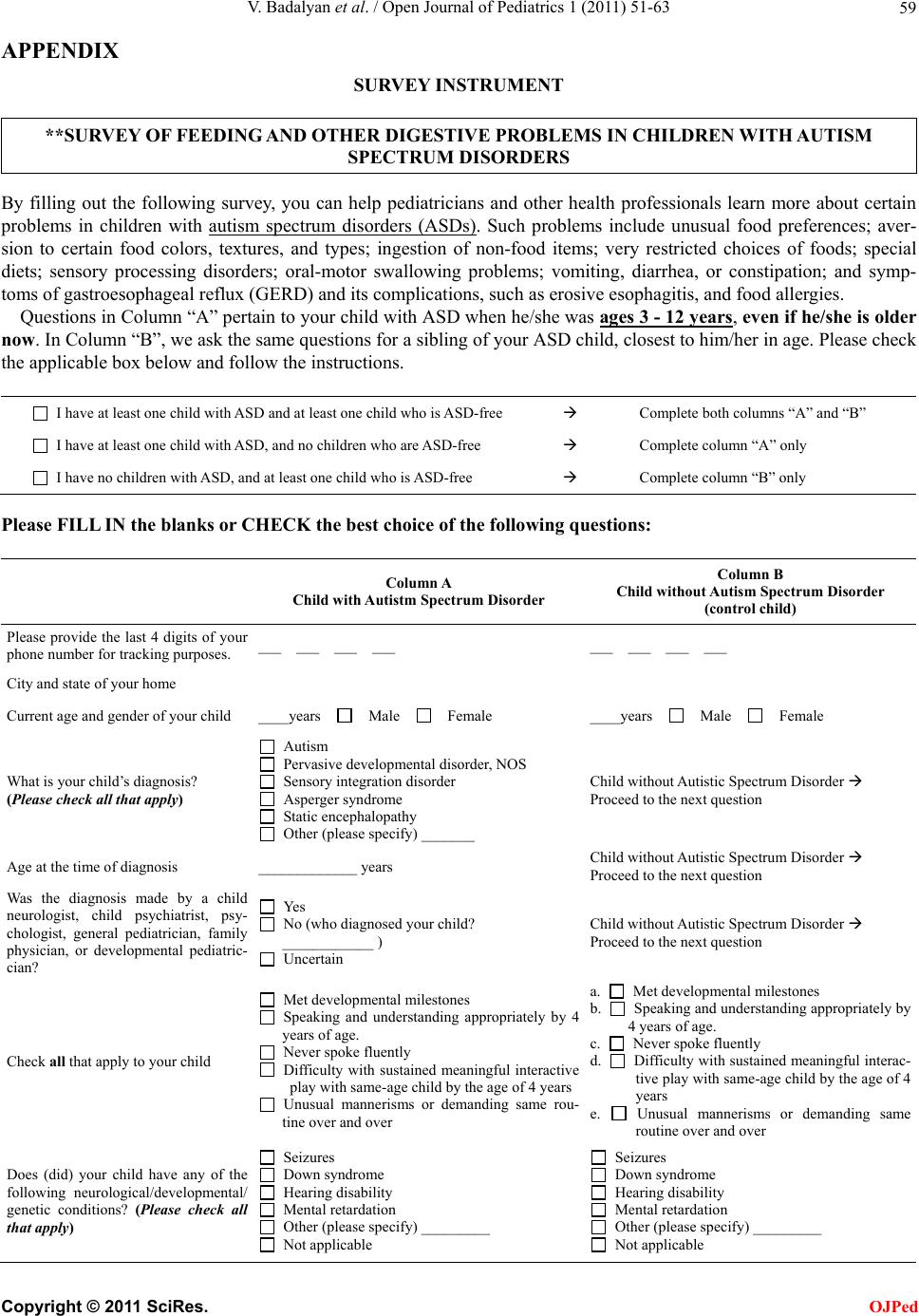

|