M. C. Schwartz et al. / Open Journal of Pediatrics 1 (2011) 87-89

88

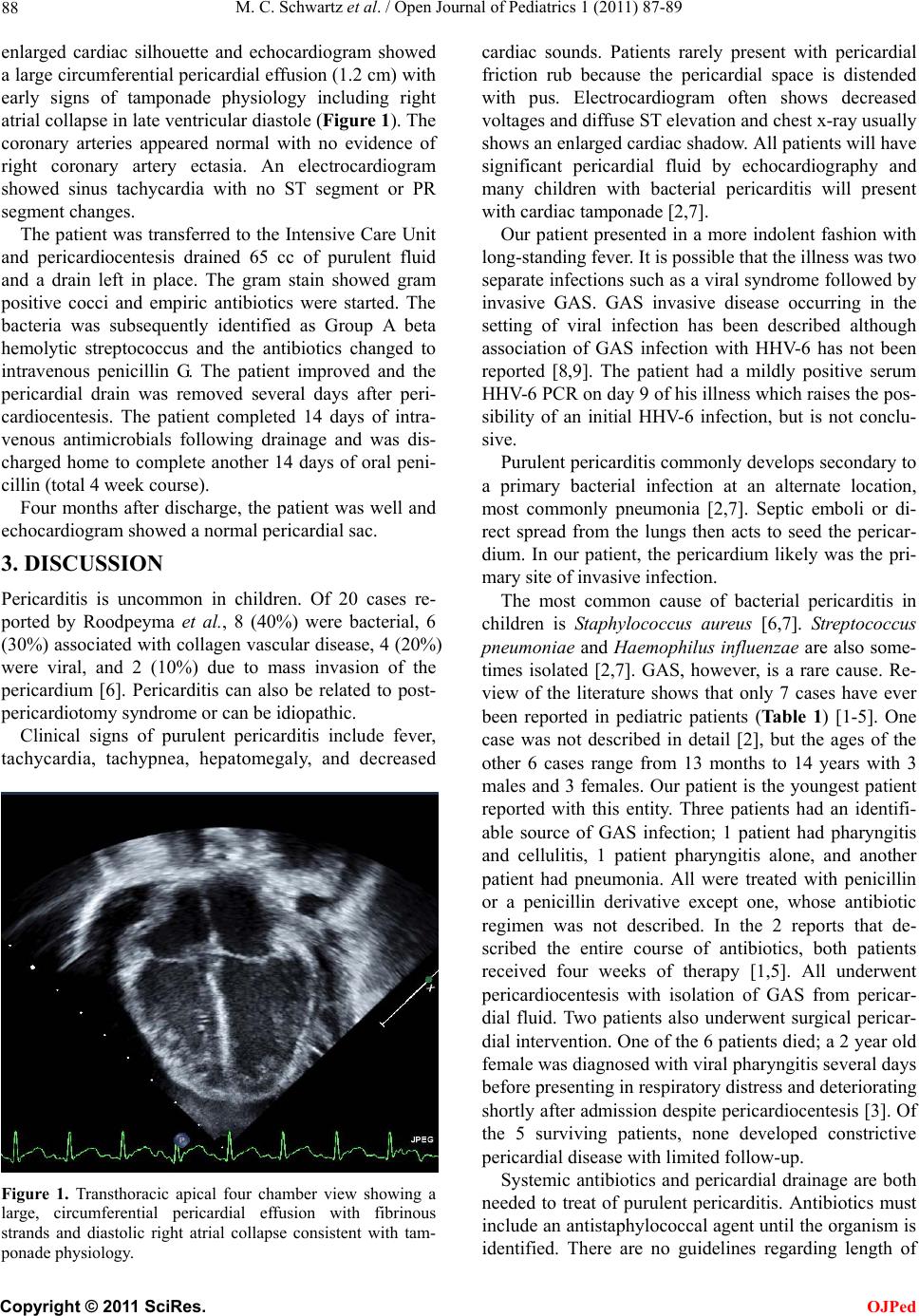

enlarged cardiac silhouette and echocardiogram showed

a large circumferential pericardial effusion (1.2 cm) with

early signs of tamponade physiology including right

atrial collapse in late ventricular diastole (Figure 1). The

coronary arteries appeared normal with no evidence of

right coronary artery ectasia. An electrocardiogram

showed sinus tachycardia with no ST segment or PR

segment changes.

The patient was transferred to the Intensive Care Unit

and pericardiocentesis drained 65 cc of purulent fluid

and a drain left in place. The gram stain showed gram

positive cocci and empiric antibiotics were started. The

bacteria was subsequently identified as Group A beta

hemolytic streptococcus and the antibiotics changed to

intravenous penicillin G. The patient improved and the

pericardial drain was removed several days after peri-

cardiocentesis. The patient completed 14 days of intra-

venous antimicrobials following drainage and was dis-

charged home to complete another 14 days of oral peni-

cillin (total 4 week course).

Four months after discharge, the patient was well and

echocardiogram showed a normal pericardial sac.

3. DISCUSSION

Pericarditis is uncommon in children. Of 20 cases re-

ported by Roodpeyma et al., 8 (40%) were bacterial, 6

(30%) associated with collagen vascular disease, 4 (20%)

were viral, and 2 (10%) due to mass invasion of the

pericardium [6]. Pericarditis can also be related to post-

pericardiotomy syndrome or can be idiopathic.

Clinical signs of purulent pericarditis include fever,

tachycardia, tachypnea, hepatomegaly, and decreased

Figure 1. Transthoracic apical four chamber view showing a

large, circumferential pericardial effusion with fibrinous

strands and diastolic right atrial collapse consistent with tam-

ponade physiology.

cardiac sounds. Patients rarely present with pericardial

friction rub because the pericardial space is distended

with pus. Electrocardiogram often shows decreased

voltages and diffuse ST elevation and chest x-ray usually

shows an enlarged cardiac shadow. All patients will have

significant pericardial fluid by echocardiography and

many children with bacterial pericarditis will present

with cardiac tamponade [2,7].

Our patient presented in a more indolent fashion with

long-standing fever. It is possible that the illness was two

separate infections such as a viral syndro me followed by

invasive GAS. GAS invasive disease occurring in the

setting of viral infection has been described although

association of GAS infection with HHV-6 has not been

reported [8,9]. The patient had a mildly positive serum

HHV-6 PCR on day 9 of his illness which raises the pos-

sibility of an initial HHV-6 infection, but is not conclu-

sive.

Purulent pericarditis co mmonly develops seco ndary to

a primary bacterial infection at an alternate location,

most commonly pneumonia [2,7]. Septic emboli or di-

rect spread from the lungs then acts to seed the pericar-

dium. In our patient, the pericardium likely was the pri-

mary site of invasive infection.

The most common cause of bacterial pericarditis in

children is Staphylococcus aureus [6,7]. Streptococcus

pneumonia e and Haemophilus influenzae are also some-

times isolated [2,7]. GAS, however, is a rare cause. Re-

view of the literature shows that only 7 cases have ever

been reported in pediatric patients (Ta b l e 1) [1-5]. One

case was not described in detail [2], but the ages of the

other 6 cases range from 13 months to 14 years with 3

males and 3 females. Our patient is the youngest patient

reported with this entity. Three patients had an identifi-

able source of GAS infection; 1 patient had pharyngitis

and cellulitis, 1 patient pharyngitis alone, and another

patient had pneumonia. All were treated with penicillin

or a penicillin derivative except one, whose antibiotic

regimen was not described. In the 2 reports that de-

scribed the entire course of antibiotics, both patients

received four weeks of therapy [1,5]. All underwent

pericardiocentesis with isolation of GAS from pericar-

dial fluid. Two patients also underwent surgical pericar-

dial intervention. One of the 6 patients died; a 2 year old

female was diagnosed with viral pharyngitis several days

before presenting in respiratory distress and deteriorating

shortly after admission despite pericardiocentesis [3]. Of

the 5 surviving patients, none developed constrictive

pericardial disease with limited follow-up.

Systemic antibiotics and pericardial drainage are both

needed to treat of purulent pericarditis. Antibiotics must

include an antistaphylococcal agent until the organism is

identified. There are no guidelines regarding length of

C

opyright © 2011 SciRes. OJPed