Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

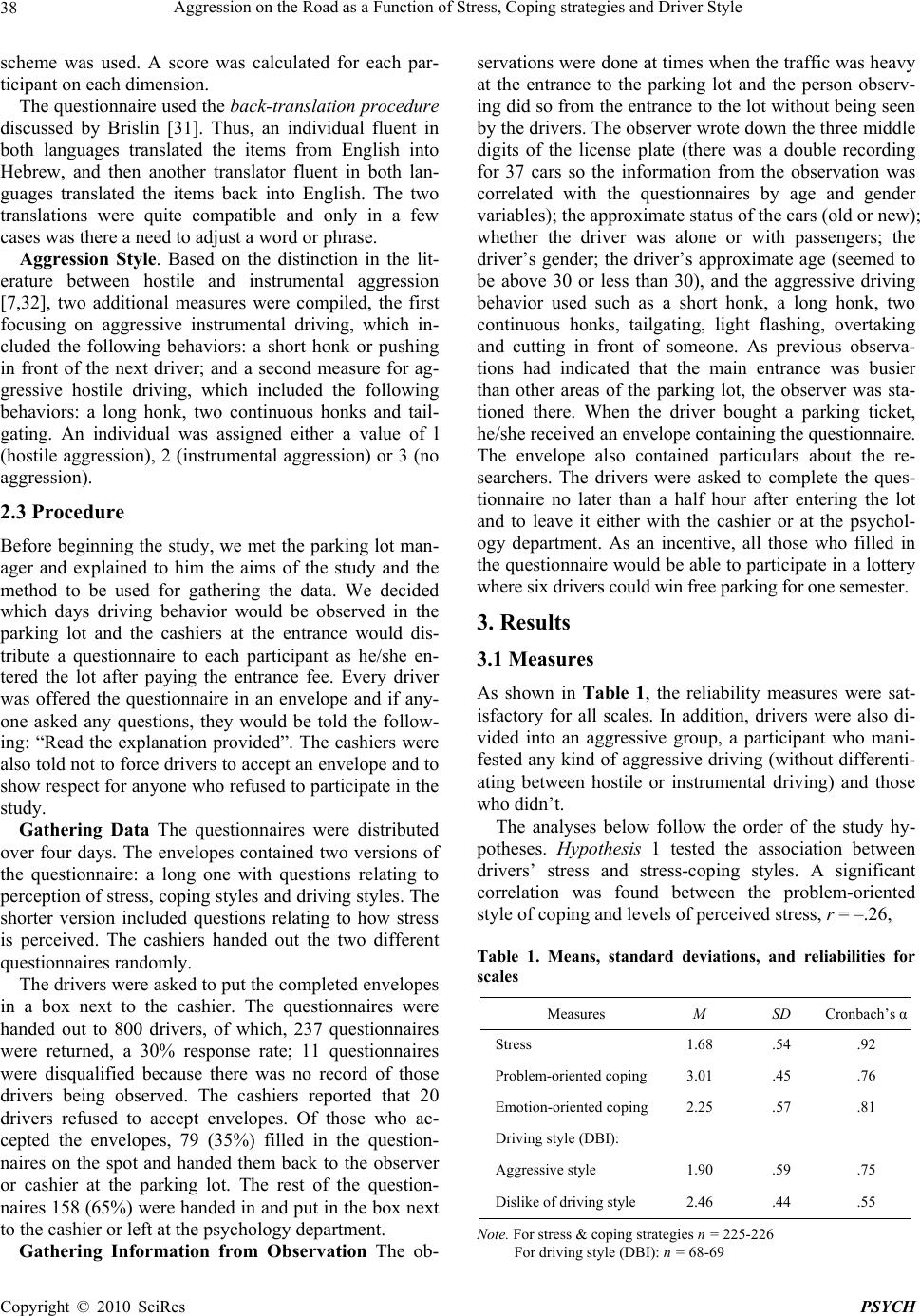

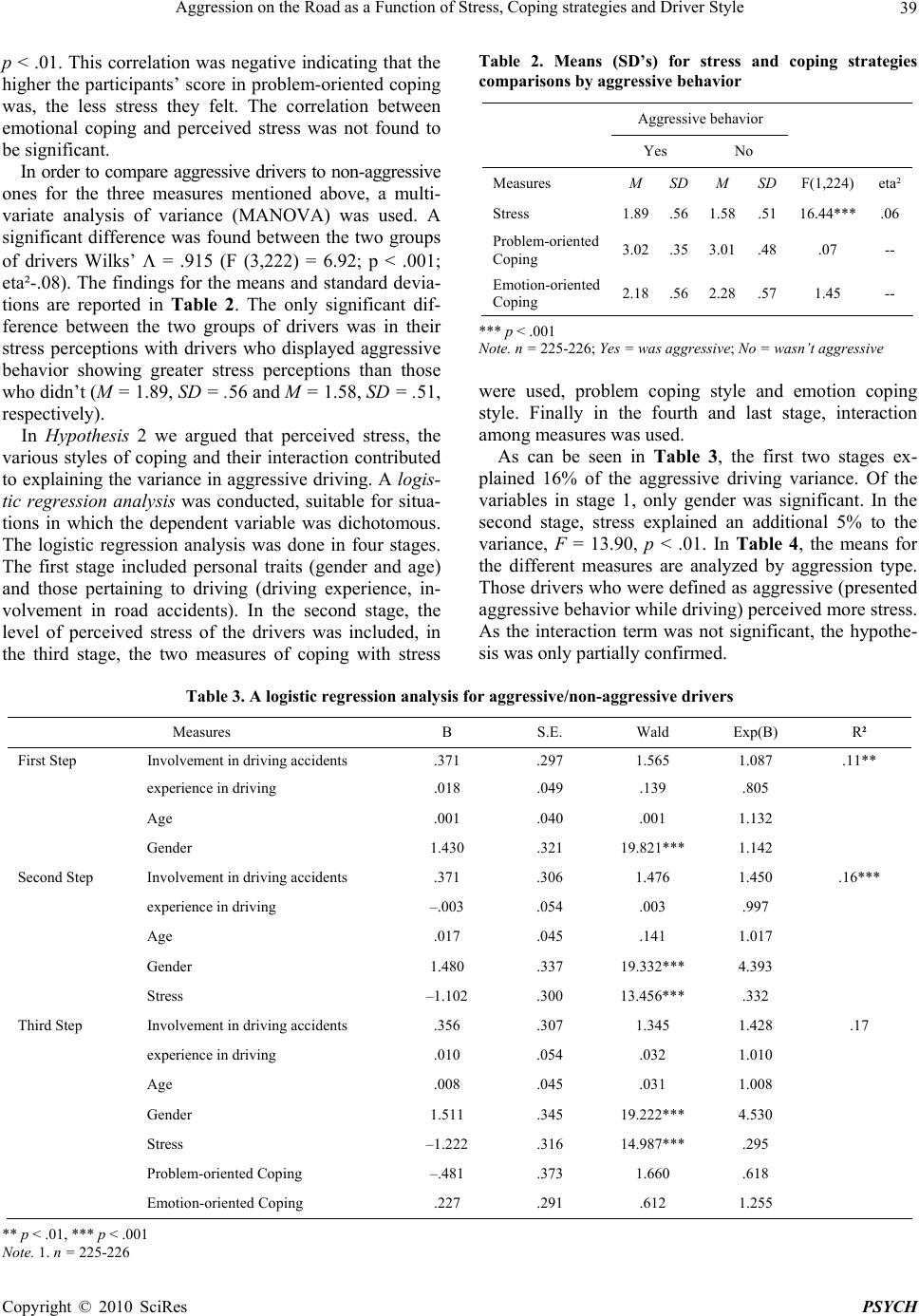

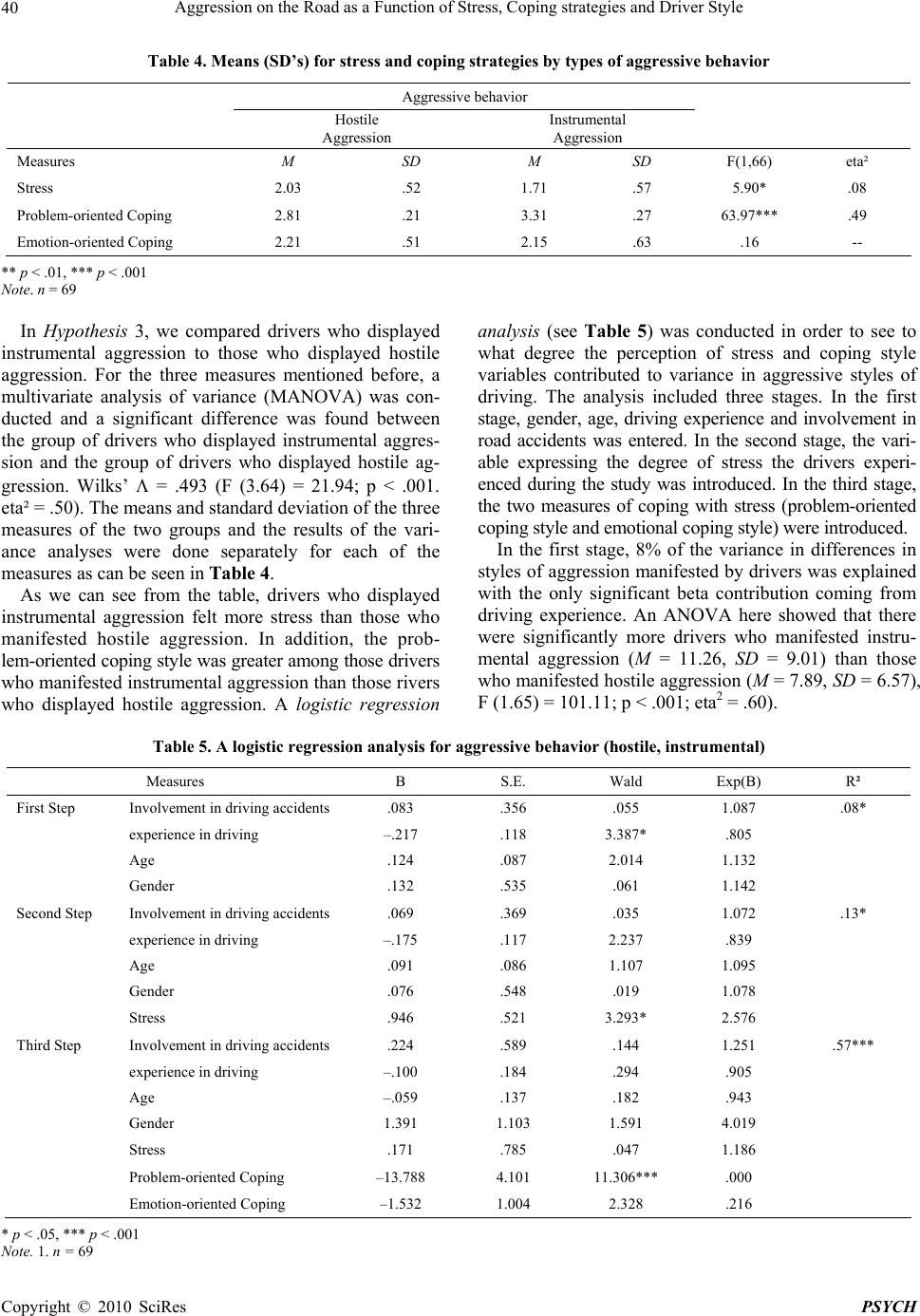

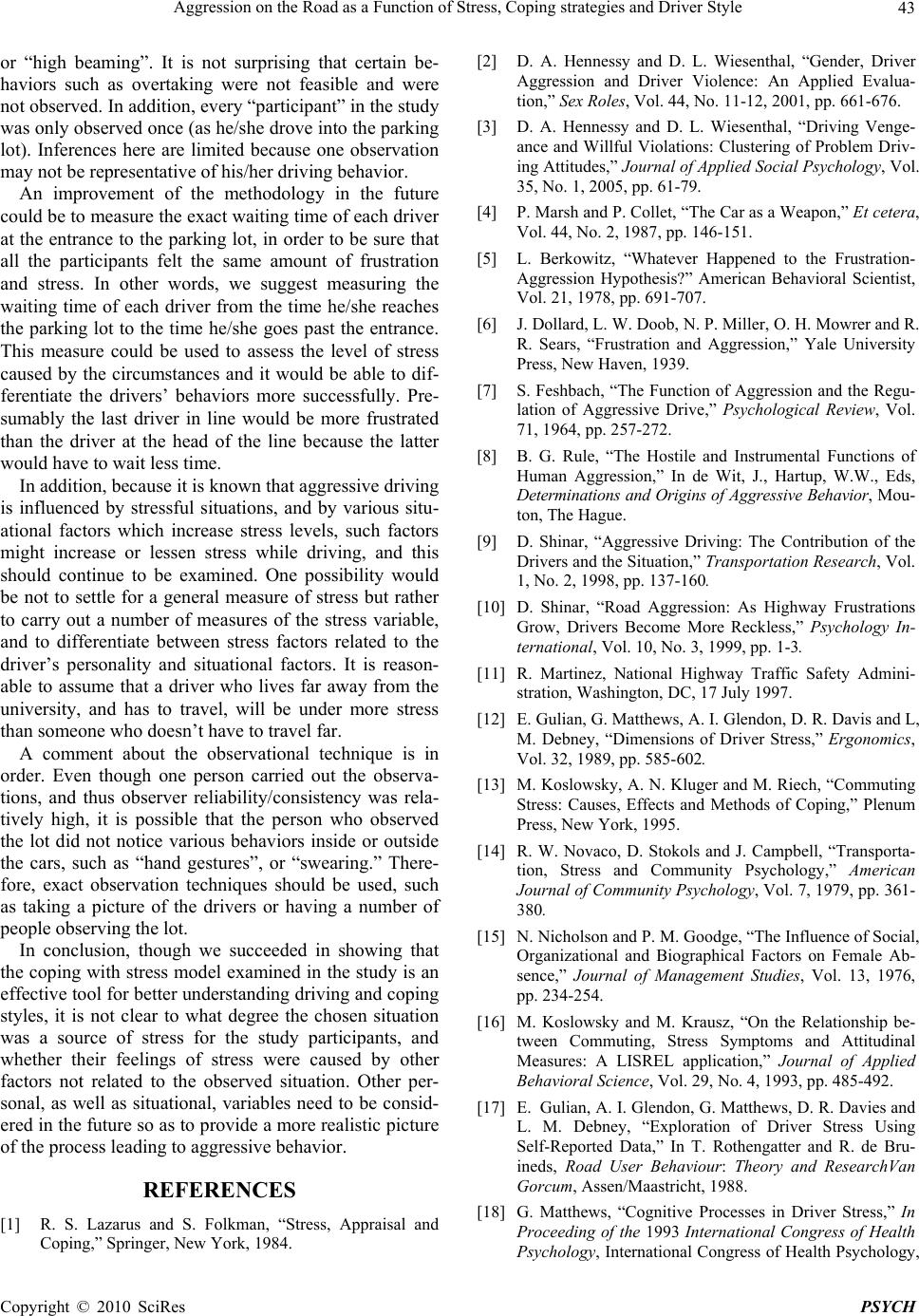

Psychology, 2010, 1: 35-44 doi:10.4236/psych.2010.11006 Published Online April 2010 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/psych) Copyright © 2010 SciRes PSYCH 35 Aggression on the Road as a Function of Stress, Coping Strategies and Driver Style Lipaz Shamoa-Nir, Meni Koslowsky Department of Psychology, Bar-Ilan University, Ramat Gan, Israel. Email: koslow@mail.biu.ac.il Received January 12th, 2010; revised January 19th, 2010; accepted January 20th, 2010. ABSTRACT According to Lazaru s and Folkman’s [1] tran sactiona l cognitive model, peop le differ in their sensitivity a nd vuln erabil- ity to stressful events. Using questionnaire and observational techniques, the model was tested as a possible explana- tion for aggressive driving behavior. Responses from 226 drivers who were also observed driving their cars provided evidence for a lin k between stress and aggressive driving as well as between problem-solving strategy as a coping de- vice in stressful situations and ho stile behaviors. In addition, analysis showed that, in general, the more years of driving experience a driver has, the more likely he/she is to respond with instrumental rather than hostile aggression. Besides support for the theoretical model, some of the practical applications as they related to highway safety and the preven- tion of traffic accidents were presented. Keywords: Dri ving Stress, Aggressive Driving, Problem-Solving Strategy, Hostile Strategy, Instrumental Stratgey 1. Introduction Road accidents and traffic offences resulting from ag- gressive driving have been a subject of interest to many researchers over the years with several studies attesting to an increase in negative outcomes. Examples range from irritability, anger, violent reactions [2,3] and even drivers shooting at each other during an argument such as who saw the specific parking space first [4]. A common explanation for these negative behaviors uses the frustra- tion-aggression model whereby a driver who has been blocked from getting to his/her destination expresses frustration which may lead to some overt expression such as harming/hurting another driver. Yet, in many situa- tions where aggression is manifested, the so-called cause of the frustration is not readily apparent. The present study applies an alternative approach, Lazarus and Folkman’s [1] transactional cognitive model, for ex- plaining drivers’ actual reactions on the road. According to the usual formulation, where frustration is followed by an aggressive act [5,6] no real distinction is made among the different types of aggression. How- ever, Feshbach’s [7] conceptualization which distin- guished between hostile and instrumental acts [8] seems quite appropriate for the driving situation. Although both types of aggression are seen as an attempt to harm an- other person, the aim of instrumental aggression is to gain something such as money, social status or territory, whereas hostile aggression is mainly aimed at causing hurt or pain. In his study on aggressive driving behavior, Shinar [9] defined instrumental aggression as actions taken by the driver that will aid his/her progress in driv- ing, or help in removing or overtaking an obstacle on the road. while hostile aggression on the road serves no pur- pose other than harming another. According to Shinar [10], the differentiation is not unambiguous and many expressions of anger on the road can be defined as either instrumental or hostile or both. Although overlap is expected between the concepts, this distinction can explain why there were fewer aggressive behaviors such as driving through a red light or honking at a driver blocking progress when the light is green (which is sometimes considered hostile) among older drivers as well as the greater number of such behaviors reported among men than women [9]. While hostile aggression gives drivers a feeling of sat- isfaction about the present difficulties in which they find themselves, it doesn’t really solve the problem at hand. At best, these actions help channel drivers’ anger while producing harm to the frustrating party. Overall, the frus- tration-aggression model, accounts for the result of the drivers’ behavior but not for the process that leads the driver from his/her feelings of frustration to the specific behavioral reaction.  Aggression on the Road as a Function of Stress, Coping strategies and Driver Style Copyright © 2010 SciRes PSYCH 36 1.1 Road Rage and Aggressive Driving Recently, a new term, road rage, has been introduced into the discussion on aggressive driving. Although many people view these terms as similar, in fact, it is likely that the terms have specific connotations [9]. The American National Safety Council has tried to differentiate between them by defining aggressive driving as “movement or activity using a vehicle that endangers or will endanger people or property,” which is a traffic violation [11] whereas road rage is not necessarily a traffic offence and is seen as “an attack initiated by the driver of the car or a passenger, on a driver of another car or its passenger, using a car or other dangerous vehicle, this anger being the result of an incident or event on the road during driv- ing” [11]. Examples are tailgating, deliberately blocking progress, honking, and even verbally or physically at- tacking a driver [9]. The present study applies the dis- tinction between aggressive acts for explaining these behaviors. 1.2 Commuting Stress Many investigators agree that driving is a complex activ- ity, often accompanied by stress [12]. The relevant stim- uli and responses associated with the commuting process are a relatively new concern for stress researchers and incorporate various environmental, personal, and situ- ational sources [13]. Among the effects that have been investigated here are physiological [14], psychological [14] or organizational outcomes [15]. The commuting stress model postulated by Koslowsky et al. [13] com- prises several stages relating to stress-causing factors such as distance and time, how subjective stress is con- ceived, and how the potential negative outcomes relate to each other. A popular type of research issue has been to identify moderators of the stress-strain relationship. For example, there is evidence that there are different levels of stress associated with mode of travel. Findings by Koslowsky and Krausz [16] showed that stress symptoms were greater among nurses who drove their cars to work, compared to those who commuted by public transport. 1.3 Driving Behavior Styles In studying drivers’ stress, Gulian, Matthews, Glendon, Davis & Debney [17] argued that drivers’ stress-related behavior depends on the driver’s appraisal of the situa- tion, in that driving skills depend on the individual’s ability to cope with stress. They identified five distinct and independent categories of driving under stress and assessed them by using the Driving Behavior Inventory (DBI). Among the styles relevant here are “dislike of driving” and “aggression.” Questions on “dislike of driving” deal with anxiety, dissatisfaction and lack of confidence, especially under difficult driving conditions. These mainly relate to emotional stress symptoms such as tension, and depressed mood states as a result of driv- ing [18]. Questions on aggressive driving style deal with feelings of anger, frustration, lack of patience and a negative perception of other drivers who are sometimes seen as hostile and threatening. “Aggression” questions deal with annoyance while driving, lack of patience and aggressive actions, especially when progress is blocked by other drivers [19]. Research dealing with the associa- tion between driving styles and cognitive measures of coping found that drivers’ stress measures and resulting behavior can be characterized by the following: drivers who scored high on “dislike of driving” tended to cope with stress while driving by using emotional coping strategies (for instance self-criticism) which increased feelings of apprehension about traffic. Drivers who scored high on “aggression” used direct confrontation strategies [19] which included tailgating and frequent overtaking [18]. In addition, drivers who scored high on “aggression” reported that they made more mistakes while driving and committed more traffic violations such as speeding [20]. “Dislike of driving” and “aggression” were found to be linked to processes such as cognitive assessments of cir- cumstances involving stress and ways of coping with them [20], including emotional reactions and reactions to stress. 1.4 Coping with Stress People differ in their sensitivity and reactions to stressful situations [21]. When drivers are stressed, their aggres- sive behavior may be easier to understand using Lazarus and Folkman’s [1] cognitive model which describes coping styles in stressful situations. The model suggested by these researchers has been one of the most influential formulations in explaining both theory and empirical findings on coping strategies in stressful situations [22-25]. Cognitive evaluation starts with the individual appraising the dangers of the situation. Next, the indi- vidual analyzes ways to cope with the situation [1] so as to regulate emotions which may lead to modifying the specific stress-strain link. An individual who experiences a stressful situation can react in one of two ways: emotion-focused coping de- fined as decreasing emotional stress including strategies such as abstention, blaming others, keeping distance, selective attention, and finding something valuable in negative events. On the other hand, problem-focused coping includes problem-solving strategies and dealing effectively with stress stimuli. Examples include focus- ing on the overall problem, attempting to define the problem, suggesting alternative solutions, considering the alternatives, choosing one of them, and taking action. An overlooked but interesting area is the link between styles of coping with stress, and attitudes towards driving and related emotions [12]. Differences in coping styles  Aggression on the Road as a Function of Stress, Coping strategies and Driver Style Copyright © 2010 SciRes PSYCH 37 among drivers are reflected in different attitudes towards driving [17,18,26]. Generally, in these studies, data were collected from questionnaires completed by participants but aggressive reactions of drivers were not tested in real time, i.e., on the road. In addition, the instruments for comparing coping styles while driving were limited to developing measures and scales to test examine stress and copings, without examining the process of driving while under stress. Based on the studies in the area using stress, driving style, and coping processes, the following specific hy- potheses concerning aggression on the road were formu- lated: Hypothesis 1: Drivers who use a problem solving ap- proach to stress will experience less perceived stress. No relationship between emotional coping style and per- ceived stress is expected. Hypothesis 2: Perceived stress, coping style, individu- ally and as an interaction term, predict who is likely to be aggressive on the road. Hypothesis 3: Drivers who use instrumental aggression will manifest more stress and use more of a prob- lem-oriented style of coping than those who use hostile aggression while driving. Hypothesis 4: There will be a link between perceived stress and driving style such that perceived stress of ag- gressive style drivers will be greater than the perceived stress of dislike driving style drivers. 2. Method 2.1 Sample Participants included 226 drivers (67% women) affiliated with a university in central Israel. Mean age for the group was 29.0 (SD = 6.73), ranging from 19-74 with an aver- age number of years of education, 14.8 (SD = 2.92), ranging from 8-30 years. About 49% were students, 43% salaried employees, 4% self-employed, 3% unemployed and less than 1% were soldiers or pensioners. The average number of years driving was 10.27 (SD = 8.73), ranging from 1-59 years with about 89% saying they drove their cars almost every day The av- erage number of kilometers driven in the middle of the week was 186.91 (SD = 220.72) and the range was between 1-2000 kilometers. Nearly 49% of the partici- pants had been involved in road accidents. Of those involved in accidents, 75% were young drivers (30 or below). Among those who had committed a traffic violation, about 31% had at least one or more tickets for speeding. During the period of observation, 31% of the drivers displayed one aggressive behavior including 7% who sounded a “short honk”; 1% a “long honk”; 3% “two consecutive honks”; 9% who had “cut in” on other driv- ers; and 12% who tailgaited. 2.2 Instruments The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. The Speilberger [27] State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, as translated into Hebrew by Teichman and Mellik [28], was used here. Participants are asked to rank the strength of their present feelings on a scale from 1-not at all to 4-very much. For the present analysis, the relevant items were those that focused on an emotional description related to stress at- tributes that a person feels “at a given moment”, such as serenity, safety, anger etc. A person’s anxiety level is determined by combining the individual responses with a higher score indicating a higher state of anxiety. A Checklist for Coping Styles. The questionnaire was translated into Hebrew [29] from the original article by Folkman and Lazarus [22] The Ways of Coping Checklist. The questionnaire includes 43 items describing various strategies people use in order to cope with stressful situa- tions. The participant is asked to what degree he/she uses each strategy when facing stressful situations. A four factor solution for coping styles, similar to Lazarus and Folkman, was obtained: coping focused on the problem (12 items), coping focused on emotion (12 items), searching for social support (8 items), and denial (5 items). Cronbach’s alpha reliability on each of the 4 fac- tors was found to be higher than 0.74. Four factor scores were compiled with a high score indicating that this par- ticular strategy was used often. Driving Behavior Inventory (DBI). The items in the DBI [17] were translated into Hebrew. The first part of the original questionnaire related to biographical ques- tions such as driving experience and driving habits. The second part consisting of 37 general stress statements related to being on the road and reactions pertaining to the driving experience. Gulian et al. [12] found that these statements reflected five dimensions of stress while driving, expressing the participant’s beliefs and reactions. Example of items and the relevant dimension include the following: “I overtake other cars whenever I get the chance.”(Expression of aggression);”I am aware of dif- ficulties on the road” (expression of alertness);”I am irri- tated when I overtake another car”(expression of irrita- tion when overtaking); “I feel satisfaction when overtak- ing another car” (expression of tension when overtaking); “Driving usually makes me frustrated” (expression of aversion to driving-dislike driving style); “I am usually patient when facing heavy traffic” (Expression of general driver stress). On the original DBI questionnaire, participants had to mark gradations on a scale (100 mm long) showing to what degree they agreed with the above expressions. Matthews et al. [30] recoded the items and used the fol- lowing scale: 1) “doesn’t describe how I feel”; 2) “de- scribes me to a certain extent”; 3) “describes me well”; 4. “describes me very well”. In the present study, this  Aggression on the Road as a Function of Stress, Coping strategies and Driver Style Copyright © 2010 SciRes PSYCH 38 scheme was used. A score was calculated for each par- ticipant on each dimension. The questionnaire used the back-translation procedure discussed by Brislin [31]. Thus, an individual fluent in both languages translated the items from English into Hebrew, and then another translator fluent in both lan- guages translated the items back into English. The two translations were quite compatible and only in a few cases was there a need to adjust a word or phrase. Aggression Style. Based on the distinction in the lit- erature between hostile and instrumental aggression [7,32], two additional measures were compiled, the first focusing on aggressive instrumental driving, which in- cluded the following behaviors: a short honk or pushing in front of the next driver; and a second measure for ag- gressive hostile driving, which included the following behaviors: a long honk, two continuous honks and tail- gating. An individual was assigned either a value of l (hostile aggression), 2 (instrumental aggression) or 3 (no aggression). 2.3 Procedure Before beginning the study, we met the parking lot man- ager and explained to him the aims of the study and the method to be used for gathering the data. We decided which days driving behavior would be observed in the parking lot and the cashiers at the entrance would dis- tribute a questionnaire to each participant as he/she en- tered the lot after paying the entrance fee. Every driver was offered the questionnaire in an envelope and if any- one asked any questions, they would be told the follow- ing: “Read the explanation provided”. The cashiers were also told not to force drivers to accept an envelope and to show respect for anyone who refused to participate in the study. Gathering Data The questionnaires were distributed over four days. The envelopes contained two versions of the questionnaire: a long one with questions relating to perception of stress, coping styles and driving styles. The shorter version included questions relating to how stress is perceived. The cashiers handed out the two different questionnaires randomly. The drivers were asked to put the completed envelopes in a box next to the cashier. The questionnaires were handed out to 800 drivers, of which, 237 questionnaires were returned, a 30% response rate; 11 questionnaires were disqualified because there was no record of those drivers being observed. The cashiers reported that 20 drivers refused to accept envelopes. Of those who ac- cepted the envelopes, 79 (35%) filled in the question- naires on the spot and handed them back to the observer or cashier at the parking lot. The rest of the question- naires 158 (65%) were handed in and put in the box next to the cashier or left at the psychology department. Gathering Information from Observation The ob- servations were done at times when the traffic was heavy at the entrance to the parking lot and the person observ- ing did so from the entrance to the lot without being seen by the drivers. The observer wrote down the three middle digits of the license plate (there was a double recording for 37 cars so the information from the observation was correlated with the questionnaires by age and gender variables); the approximate status of the cars (old or new); whether the driver was alone or with passengers; the driver’s gender; the driver’s approximate age (seemed to be above 30 or less than 30), and the aggressive driving behavior used such as a short honk, a long honk, two continuous honks, tailgating, light flashing, overtaking and cutting in front of someone. As previous observa- tions had indicated that the main entrance was busier than other areas of the parking lot, the observer was sta- tioned there. When the driver bought a parking ticket, he/she received an envelope containing the questionnaire. The envelope also contained particulars about the re- searchers. The drivers were asked to complete the ques- tionnaire no later than a half hour after entering the lot and to leave it either with the cashier or at the psychol- ogy department. As an incentive, all those who filled in the questionnaire would be able to participate in a lottery where six drivers could win free parking for one semester. 3. Results 3.1 Measures As shown in Table 1, the reliability measures were sat- isfactory for all scales. In addition, drivers were also di- vided into an aggressive group, a participant who mani- fested any kind of aggressive driving (without differenti- ating between hostile or instrumental driving) and those who didn’t. The analyses below follow the order of the study hy- potheses. Hypothesis 1 tested the association between drivers’ stress and stress-coping styles. A significant correlation was found between the problem-oriented style of coping and levels of perceived stress, r = –.26, Table 1. Means, standard deviations, and reliabilities for scales Measures M SD Cronbach’s α Stress 1.68 54. 92. Problem-oriented coping3.01 .45 76. Emotion-oriented coping2.25 57. .81 Driving style (DBI): Aggressive style 1.90 59. 75. Dislike of driving style 2.46 44. 55. Note. For stress & coping strategies n = 225-226 For driving style (DBI): n = 68-69  Aggression on the Road as a Function of Stress, Coping strategies and Driver Style Copyright © 2010 SciRes PSYCH 39 p < .01. This correlation was negative indicating that the higher the participants’ score in problem-oriented coping was, the less stress they felt. The correlation between emotional coping and perceived stress was not found to be significant. In order to compare aggressive drivers to non-aggressive ones for the three measures mentioned above, a multi- variate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was used. A significant difference was found between the two groups of drivers Wilks’ = .915 (F (3,222) = 6.92; p < .001; eta²-.08). The findings for the means and standard devia- tions are reported in Table 2. The only significant dif- ference between the two groups of drivers was in their stress perceptions with drivers who displayed aggressive behavior showing greater stress perceptions than those who didn’t (M = 1.89, SD = .56 and M = 1.58, SD = .51, respectively). In Hypothesis 2 we argued that perceived stress, the various styles of coping and their interaction contributed to explaining the variance in aggressive driving. A logis- tic regression analysis was conducted, suitable for situa- tions in which the dependent variable was dichotomous. The logistic regression analysis was done in four stages. The first stage included personal traits (gender and age) and those pertaining to driving (driving experience, in- volvement in road accidents). In the second stage, the level of perceived stress of the drivers was included, in the third stage, the two measures of coping with stress Table 2. Means (SD’s) for stress and coping strategies comparisons by aggressive behavior Aggressive behavior Yes No Measures M SDM SD F(1,224) eta² Stress 1.89.561.58 .51 16.44***.06 Problem-oriented Coping 3.02.353.01 .48 .07 -- Emotion-oriented Coping 2.18.562.28 .57 1.45 -- *** p < .001 Note. n = 225-226; Yes = was aggressive; No = wasn’t aggressive were used, problem coping style and emotion coping style. Finally in the fourth and last stage, interaction among measures was used. As can be seen in Table 3, the first two stages ex- plained 16% of the aggressive driving variance. Of the variables in stage 1, only gender was significant. In the second stage, stress explained an additional 5% to the variance, F = 13.90, p < .01. In Table 4, the means for the different measures are analyzed by aggression type. Those drivers who were defined as aggressive (presented aggressive behavior while driving) perceived more stress. As the interaction term was not significant, the hypothe- sis was only partially confirmed. Table 3. A logistic regression analysis for aggressive/non-aggressive drivers Measures B S.E. Wald Exp(B) R² First Step Involvement in driving accidents .371 .297 1.565 1.087 .11** experience in driving .018 .049 .139 .805 Age .001 .040 .001 1.132 Gender 1.430 .321 19.821*** 1.142 Second Step Involvement in driving accidents .371 .306 1.476 1.450 .16*** experience in driving –.003 .054 .003 .997 Age .017 .045 .141 1.017 Gender 1.480 .337 19.332*** 4.393 Stress –1.102 .300 13.456*** .332 Third Step Involvement in driving accidents .356 .307 1.345 1.428 17. experience in driving .010 .054 .032 1.010 Age .008 .045 .031 1.008 Gender 1.511 .345 19.222*** 4.530 Stress –1.222 .316 14.987*** 295. Problem-oriented Coping –.481 .373 1.660 618. Emotion-oriented Coping .227 .291 .612 1.255 ** p < .01, *** p < .001 Note. 1. n = 225-226  Aggression on the Road as a Function of Stress, Coping strategies and Driver Style Copyright © 2010 SciRes PSYCH 40 Table 4. Means (SD’s) for stress and coping strategies by types of aggressive behavior Aggressive behavior Hostile Aggression Instrumental Aggression Measures M SD M SD F(1,66) eta² Stress 2.03 .52 1.71 .57 5.90* .08 Problem-oriented Coping 2.81 .21 3.31 .27 63.97*** .49 Emotion-oriented Coping 2.21 .51 2.15 .63 .16 -- ** p < .01, *** p < .001 Note. n = 69 In Hypothesis 3, we compared drivers who displayed instrumental aggression to those who displayed hostile aggression. For the three measures mentioned before, a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was con- ducted and a significant difference was found between the group of drivers who displayed instrumental aggres- sion and the group of drivers who displayed hostile ag- gression. Wilks’ = .493 (F (3.64) = 21.94; p < .001. eta² = .50). The means and standard deviation of the three measures of the two groups and the results of the vari- ance analyses were done separately for each of the measures as can be seen in Table 4. As we can see from the table, drivers who displayed instrumental aggression felt more stress than those who manifested hostile aggression. In addition, the prob- lem-oriented coping style was greater among those drivers who manifested instrumental aggression than those rivers who displayed hostile aggression. A logistic regression analysis (see Table 5) was conducted in order to see to what degree the perception of stress and coping style variables contributed to variance in aggressive styles of driving. The analysis included three stages. In the first stage, gender, age, driving experience and involvement in road accidents was entered. In the second stage, the vari- able expressing the degree of stress the drivers experi- enced during the study was introduced. In the third stage, the two measures of coping with stress (problem-oriented coping style and emotional coping style) were introduced. In the first stage, 8% of the variance in differences in styles of aggression manifested by drivers was explained with the only significant beta contribution coming from driving experience. An ANOVA here showed that there were significantly more drivers who manifested instru- mental aggression (M = 11.26, SD = 9.01) than those who manifested hostile aggression (M = 7.89, SD = 6.57), F (1.65) = 101.11; p < .001; eta2 = .60). Table 5. A logistic regression analysis for aggressive behavior (hostile, instrumental) Measures B S.E. Wald Exp(B) R² First Step Involvement in driving accidents .083 .356 .055 1.087 .08* experience in driving –.217 .118 3.387* .805 Age .124 .087 2.014 1.132 Gender .132 .535 .061 1.142 Second Step Involvement in driving accidents .069 .369 .035 1.072 .13* experience in driving –.175 .117 2.237 .839 Age .091 .086 1.107 1.095 Gender .076 .548 .019 1.078 Stress .946 .521 3.293* 2.576 Third Step Involvement in driving accidents .224 .589 .144 1.251 .57*** experience in driving –.100 .184 .294 .905 Age –.059 .137 .182 .943 Gender 1.391 1.103 1.591 4.019 Stress .171 .785 .047 1.186 Problem-oriented Coping –13.788 4.101 11.306*** .000 Emotion-oriented Coping –1.532 1.004 2.328 .216 * p < .05, *** p < .001 Note. 1. n = 69  Aggression on the Road as a Function of Stress, Coping strategies and Driver Style Copyright © 2010 SciRes PSYCH 41 In the second stage, level of stress added an additional 5% to explained variance. Interestingly, an ANOVA (see Table 6) indicated that the drivers who manifested hos- tile aggression manifested significantly greater levels of stress than those drivers who manifested instrumental aggression. In the third stage, where coping styles were included, an additional 44% of variance was explained, all of which can be attributed to the problem-oriented coping style (B = –13.788, p < .001) a careful examination of this relationship (Table 6) shows us that drivers who scored high in this coping style were inclined to be in- strumentally aggressive. In stage 4, no additional signifi- cant variance was explained. In total, 57% (p < .001) of variance was explained by the logistic regression. For Hypothesis 4, we examined whether there would be differences in drivers’ stress depending on driving style such that drivers displaying an aggressive style would feel more stress than those drivers who dislike driving. A Pearson’s correlation analysis showed that there was a significant correlation between aggressive driving style and feeling of stress, r = .38; p < .01. The more aggressive the drivers were, the more stress they felt. No significant correlation was found between dislike of driving and perceived stress (p > .05). 4. Discussion The findings supported the contention that drivers who displayed aggressive driving behavior showed higher levels of stress than drivers who didn’t display aggres- sive behavior while driving. Although no link was ob- served between stress coping style and aggression, there was some evidence that drivers who display a high prob- lem-oriented coping style tended to display more instru- mental aggression than hostile aggression. Moreover, drivers whose driving style was characterized as the dis- like group were inclined to react emotionally when cop- ing with stress. Using Folkman and Lazurus’ Cognitive Model which describes coping with stress as an ongoing process of evaluation, we were able to explain to some extent the process that takes place when drivers express aggression or anger while driving especially when facing stressful situations. Overall, stress experienced by drivers as well Table 6. Means (SD’s) for aggressive behavior comparisons by driving style (Aggressive, Dislike of Driving) Aggressive behavior Yes No Measures M SD M SD F(1,224)eta² Aggressive style 2.18 .68 1.74 .49 9.15** .12 Dislike of driving style 2.34 .44 2.53 .43 2.97 -- Note. Yes = was aggressive; No = wasn’t aggressive n = 68; ** p < .01 as their coping styles influences is associated with their behavior on the road. This strengthened our basic as- sumption that the frustration-aggression model used up to now by various researchers [9,33] to explain aggressive behavior of drivers on the roads, does not offer a suffi- cient or consistent explanation of drivers’ aggressive reactions. It does not fully explain the process from the moment the driver experiences frustration to the actual behavioral reaction. Among the new insights into driving behavior revealed by the data was the importance of stress perceptions and coping styles. 4.1 Stress and Coping with Stress Drivers who displayed aggressive behavior had higher levels of stress than drivers who didn’t display aggres- sive behavior. These findings were consistent with ear- lier literature that aggressive behavior was correlated with reports of the driving experience as a stressful event [2,3]. Our support here of this contention is also consistent with findings that drivers suffering from ele- vated levels of stress tended to perceive other drivers as a source of this emotion and causing them to react more aggressively towards the other driver, a form of road rage [12,17]. Nevertheless, no direct link was found between coping style, stress and driver aggression. Ag- gressive and non-aggressive drivers were not distin- guished by their coping style indicating that driving usually involves stress and that stress is a common fac- tor that exists for all drivers [17,20]. As already re- ported in the literature, clear stressor stimuli such as type and length of journey [34] or lack of control in many driving situations [13] is a common feature of most commuting experiences. It is safe to say that as soon as the level of stress is elevated to a certain point, drivers are prone to act aggressively, regardless of cause or individual style of coping with stress. Researchers attempting to identify the circumstances under which drivers choose to use violence against other drivers in order to solve problems on the road may want to consider the stress variable as a probable main or con- tributing cause. Our claim here is that drivers experienc- ing elevated levels of stress tended to blame other drivers and one way of dealing with the stress was to behave aggressively, if not violently, towards them. In the study, although drivers entering the parking lot were all ex- posed to the same conditions, aggressive tendencies were reported mainly among those who perceived stress. Those drivers who score high on the problem-oriented coping style tend to solve problems through instrumental aggression, which is not meant to harm people and can even be considered as a “healthy” way of coping with stress while driving. This assumption is supported by the regression analysis which showed that the coping with stress variable had less effect on aggressive behavior.  Aggression on the Road as a Function of Stress, Coping strategies and Driver Style Copyright © 2010 SciRes PSYCH 42 Therefore, the problem-oriented coping style served as a sort of moderating variable between perceived stress while driving and aggression. Moreover, the negative correlation between the task-oriented coping style and perceived stress appears to indicate that drivers with this kind of coping style are not inclined or tempted to react violently, but rather choose behavior that mitigates their feeling of stress. The assumptions underlying the examination of driver style and its relationship to coping with stress and ex- pressions of aggression while driving were partially up- held. The question is whether there is a link between the driving styles categorized as “aggressive driving” and “dislike of driving” and styles of coping [1] and aggres- sive response. In correlation analyses, a connection was found between aggressive driving style and perceived stress. The higher the drivers scored on the aggressive driving style measure, the greater the feeling of stress. In our observations, we noted that the more aggressive drivers were indeed those with an aggressive driving style score. These findings are also compatible with an- other finding, namely, drivers who reacted aggressively, as compared to the non-aggressive ones, reported ex- periencing higher perceived levels of stress. It should be noted that in spite of the obvious connection between aggressive driving style and high levels of stress, result- ing in aggressive driving, there are no field or empirical studies that have dealt with these associations. In parallel, we found that those drivers who are averse to driving cope with stress emotionally. This finding is a replication of previous reports where drivers with high levels of driving aversion preferred emotional reaction to stress rather than behavioral reactions. These drivers reported feeling worried about driving and handling the traffic but coped with the stress of driving by using emotional cop- ing strategies, such as self-blame or self-criticism [20]. Because they are inclined to blame themselves, it would seem they prefer an internalized cognitive-emotional reaction and reject an overt negative behavior that may not be considered as effective. 4.2 Theoretical Contribution In addition to using the cognitive model of coping with stress [1] to explain the influence of stress on drivers’ reaction, this study has provided a specific, theoretical contribution in defining aggressive behavior while driv- ing. The research literature lacks a clear definition of road anger or aggressive driving and it is difficult to dis- tinguish between various aggressive expressions while driving. Since a consistent and comprehensive definition of aggressive driving is missing [35], lack of order and an inability to test hypotheses characterize the field. By dividing aggression into two types or categories, it is possible to portray drivers using measures of stress and coping styles. The first type includes aggressive behavior that acts as a practical and deliberate solution to a prob- lem on the road, whether by avoiding the situation or by hurting others. The second type includes hostile behav- iors for the purpose of getting rid of anger or fury which are not connected to the problem. A partial answer to the query whether road rage is a useful [36] or redundant [35] phrase was provided here. It would appear that hostile behaviors described in the present study include some of the actions that typify “road rage.” Such hostile behavior is purposely meant to hurt other drivers and is different qualitatively from instrumental behaviors. We think that this study makes an important contribu- tion in clarifying both the process and outcome of the driving experience. By providing definitions and appro- priate categorizations, it is now possible to begin “talking the same language.” It is worthwhile exploring other avenues doing research in the future on drivers’ tenden- cies to behave aggressively and to recognize them as such. In spite of the connection between the drivers’ evaluation and the aggression they express, it is still not clear whether the drivers’ tendency towards aggressive driving influences the choice they make to express ag- gression (instrumental or hostile) while driving. If it does, how is it expressed (the level of aggression, frequency, etc)? 4.3 Some Applications The above findings may also have some important im- plications for road safety and prevention of road acci- dents, particularly concerning aggressive behaviors as providing a possible underlying basis for explaining why certain drivers tend to be involved in traffic violations or road accidents. In another vein, results here can be ap- plied in the compilation of training programs on road safety focusing on the human factor and the psychology of driving rather than on the traditional areas of training and prevention of road accidents: teaching road skills; regulations, infrastructures etc. It is not sufficient to fo- cus on legislation or obeying the laws. The findings pre- sented here may indicate a pressing need to focus on psychological aspects of the driving experience and ways for channeling the perceived stress into less negative consequences. Ineffective, hostile solutions can be com- pared to more effective instrumental ones with the goal of modifying behaviors that can lead to road accidents. 4.4 Limitations and Future Research In spite of the study outcomes, generalizing the results to other populations is limited for a number of reasons. The drivers were observed as they entered the parking lot. This is a situation which doesn’t necessarily represent drivers’ behavior while driving or in other situations. This situation limited the possible range of aggressive behaviors. For example, observations taken during the day did not enable observations such as “light flashing”  Aggression on the Road as a Function of Stress, Coping strategies and Driver Style Copyright © 2010 SciRes PSYCH 43 or “high beaming”. It is not surprising that certain be- haviors such as overtaking were not feasible and were not observed. In addition, every “participant” in the study was only observed once (as he/she drove into the parking lot). Inferences here are limited because one observation may not be representative of his/her driving behavior. An improvement of the methodology in the future could be to measure the exact waiting time of each driver at the entrance to the parking lot, in order to be sure that all the participants felt the same amount of frustration and stress. In other words, we suggest measuring the waiting time of each driver from the time he/she reaches the parking lot to the time he/she goes past the entrance. This measure could be used to assess the level of stress caused by the circumstances and it would be able to dif- ferentiate the drivers’ behaviors more successfully. Pre- sumably the last driver in line would be more frustrated than the driver at the head of the line because the latter would have to wait less time. In addition, because it is known that aggressive driving is influenced by stressful situations, and by various situ- ational factors which increase stress levels, such factors might increase or lessen stress while driving, and this should continue to be examined. One possibility would be not to settle for a general measure of stress but rather to carry out a number of measures of the stress variable, and to differentiate between stress factors related to the driver’s personality and situational factors. It is reason- able to assume that a driver who lives far away from the university, and has to travel, will be under more stress than someone who doesn’t have to travel far. A comment about the observational technique is in order. Even though one person carried out the observa- tions, and thus observer reliability/consistency was rela- tively high, it is possible that the person who observed the lot did not notice various behaviors inside or outside the cars, such as “hand gestures”, or “swearing.” There- fore, exact observation techniques should be used, such as taking a picture of the drivers or having a number of people observing the lot. In conclusion, though we succeeded in showing that the coping with stress model examined in the study is an effective tool for better understanding driving and coping styles, it is not clear to what degree the chosen situation was a source of stress for the study participants, and whether their feelings of stress were caused by other factors not related to the observed situation. Other per- sonal, as well as situational, variables need to be consid- ered in the future so as to provide a more realistic picture of the process leading to aggressive behavior. REFERENCES [1] R. S. Lazarus and S. Folkman, “Stress, Appraisal and Coping,” Springer, New York, 1984. [2] D. A. Hennessy and D. L. Wiesenthal, “Gender, Driver Aggression and Driver Violence: An Applied Evalua- tion,” Sex Roles , Vol. 44, No. 11-12, 2001, pp. 661-676. [3] D. A. Hennessy and D. L. Wiesenthal, “Driving Venge- ance and Willful Violations: Clustering of Problem Driv- ing Attitudes,” Journal of Applied Social Psychology, Vol. 35, No. 1, 2005, pp. 61-79. [4] P. Marsh and P. Collet, “The Car as a Weapon,” Et cetera, Vol. 44, No. 2, 1987, pp. 146-151. [5] L. Berkowitz, “Whatever Happened to the Frustration- Aggression Hypothesis?” American Behavioral Scientist, Vol. 21, 1978, pp. 691-707. [6] J. Dollard, L. W. Doob, N. P. Miller, O. H. Mowrer and R. R. Sears, “Frustration and Aggression,” Yale University Press, New Haven, 1939. [7] S. Feshbach, “The Function of Aggression and the Regu- lation of Aggressive Drive,” Psychological Review, Vol. 71, 1964, pp. 257-272. [8] B. G. Rule, “The Hostile and Instrumental Functions of Human Aggression,” In de Wit, J., Hartup, W.W., Eds, Determinations and Origins of A ggressive Behavior, Mou- ton, The Hague. [9] D. Shinar, “Aggressive Driving: The Contribution of the Drivers and the Situation,” Transportation Research, Vol. 1, No. 2, 1998, pp. 137-160. [10] D. Shinar, “Road Aggression: As Highway Frustrations Grow, Drivers Become More Reckless,” Psychology In- ternational, Vol. 10, No. 3, 1999, pp. 1-3. [11] R. Martinez, National Highway Traffic Safety Admini- stration, Washington, DC, 17 July 1997. [12] E. Gulian, G. Matthews, A. I. Glendon, D. R. Davis and L, M. Debney, “Dimensions of Driver Stress,” Ergonomics, Vol. 32, 1989, pp. 585-602. [13] M. Koslowsky, A. N. Kluger and M. Riech, “Commuting Stress: Causes, Effects and Methods of Coping,” Plenum Press, New York, 1995. [14] R. W. Novaco, D. Stokols and J. Campbell, “Transporta- tion, Stress and Community Psychology,” American Journal of Community Psychology, Vol. 7, 1979, pp. 361- 380. [15] N. Nicholson and P. M. Goodge, “The Influence of Social, Organizational and Biographical Factors on Female Ab- sence,” Journal of Management Studies, Vol. 13, 1976, pp. 234-254. [16] M. Koslowsky and M. Krausz, “On the Relationship be- tween Commuting, Stress Symptoms and Attitudinal Measures: A LISREL application,” Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, Vol. 29, No. 4, 1993, pp. 485-492. [17] E. Gulian, A. I. Glendon, G. Matthews, D. R. Davies and L. M. Debney, “Exploration of Driver Stress Using Self-Reported Data,” In T. Rothengatter and R. de Bru- ineds, Road User Behaviour: Theory and ResearchVan Gorcum, Assen/Maastricht, 1988. [18] G. Matthews, “Cognitive Processes in Driver Stress,” In Proceeding of the 1993 International Congress of Health Psychology, International Congress of Health Psychology,  Aggression on the Road as a Function of Stress, Coping strategies and Driver Style Copyright © 2010 SciRes PSYCH 44 Tokyo, 1993, pp. 90-93. [19] G. Matthews, L. Dorn, W. H. Thomas, D. R. Davis, A. I. Glendon and R. G. Taylor, “Driver Stress and Perform- ance on a Driving Simulator,” Human Factors, Vol. 40, No. 1, 1998, pp. 136-149. [20] G. Matthews, P. A. Desmond, L. Joyner, B. Carcary and K. Gilliland, “A Comprehensive Questionnaire Measure of Driver Stress and Affect,” In: Vaya, E.C. and Rothen- gatter, J.A. Eds., Traffic and transport psychology: The- ory and application, Pergamon, Amsterdam, 1997, pp. 317-324. [21] M. C. W. Peeters, B. P. Buunk and W. B. Schaufeli, “A Micro-Analytic Exploration of the Cognitive Appraisal of Daily Stressful Events at Work: The Role of Controllabil- ity,” Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, Vol. 8, 1995, pp. 127- 139. [22] S. Folkman and R. S. Lazarus, “If it Changes it must be a Process: A Study of Emotion and Coping during Three Stages of a College Examination,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 48, No. 1, 1985, pp. 150- 170. [23] S. Folkman and R. S. Lazarus, “Coping as a Mediator of Emotion,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 54, 1988, pp. 466-475. [24] S. Folkman, R. S. Lazarus, C. Dunkel-Schetter, A. Delongis and R. J. Gruen, “Dynamics of a Stressful En- counter: Cognitive Appraisal, Coping and Encounter Outcomes,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychol- ogy, Vol. 50, 1986, pp. 992-1003. [25] E. J. Peacock, P. T. P. Wong and S. T. Reker, “Relations between Appraisals and Coping Schemes: Support for the Congruence Model,” Canadian Journal of Behavioral Science, Vol. 25, pp. 65-80. [26] A. I. Glendon, L. Dorn, G. Matthews, E. Gulian, D. R. Davies and L. M. Debney, “Reliability of the Driving Be- haviour Inventory,” Egronomics, Vol. 36, 1993, pp. 719- 726. [27] C. D. Spielberger, “The Manual of State-Trait Anxiety Inventory,” Consulting Psychologists Press, Palo Alto, 1983. [28] Y. Teichman and H. Mellik, “State-Trait Anxiety Inven- tory,” Tel-Aviv University, Ramot Press, Tel-Aviv, 1976. [29] A. Avitzur, “Personal and Social Resources, Post-Trau- matic Influence after Participating in War,” M.A. Thesis, Bar-Ilan University, Ramat Gan, 1987. [30] G. Matthews, P. A. Desmond, L. Joyner, B. Carcary and K. Gilliland, “A Comprehensive Questionnaire Measure of Driver Stress and Affect,” In: Vaya E.C. and Rothen- gatter J.A. Eds., Traffic and Transport Psychology: The- ory and Application, Amsterdam: Pergamon, 1997, pp. 317-324. [31] R. W. Brislin, “Translation and Content Analysis of Oral and Written Material,” In: Triandis, H.C. and Berry, J.W. Eds., Handbook of Cross-Cultural Psychology: Method- ology, Allyn and Bacon, Boston, Vol. 2, 1980, pp. 389- 444. [32] B. A. Bettencourt, A. Talley, A. J. Benjamin and J. Val- entine, “Personality and Aggressive Behavior under Pro- voking and Neutral Conditions: A Meta-Analytic Re- view,” Psychological Bulletin, Vol. 132, 2006, pp. 751- 777. [33] A. N. Doob and A. E. Gross, “Status of Frustrator as an Inhibitor of Horn-Honking Responses,” The Journal of Soci al Psyc h ology, Vol. 76, 1968, pp. 213-218. [34] M. Koslowsky and M. Krausz, “On the Relationship be- tween Commuting, Stress Symptoms and Attitudinal Measures: A LISREL Application,” Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, Vol. 29, No. 4, 1993, pp. 485-492. [35] C. Dula and S. E. Geller, “Risky, Aggressive, or Emo- tional Driving: Addressing the Need for Consistent Communication in Research,” Journal of Safety Research, Vol. 4, No. 5, 2003, pp. 559-563. [36] J. Yu, P. C. Evans and L. Perfetti, “Road Aggression among Drinking Drivers: Alcohol and Non-Alcohol Ef- fects on Aggressive Driving and Road Rage,” Journal of Criminal Justice, Vol. 32, No. 50, 2004, pp. 421-430. |