Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

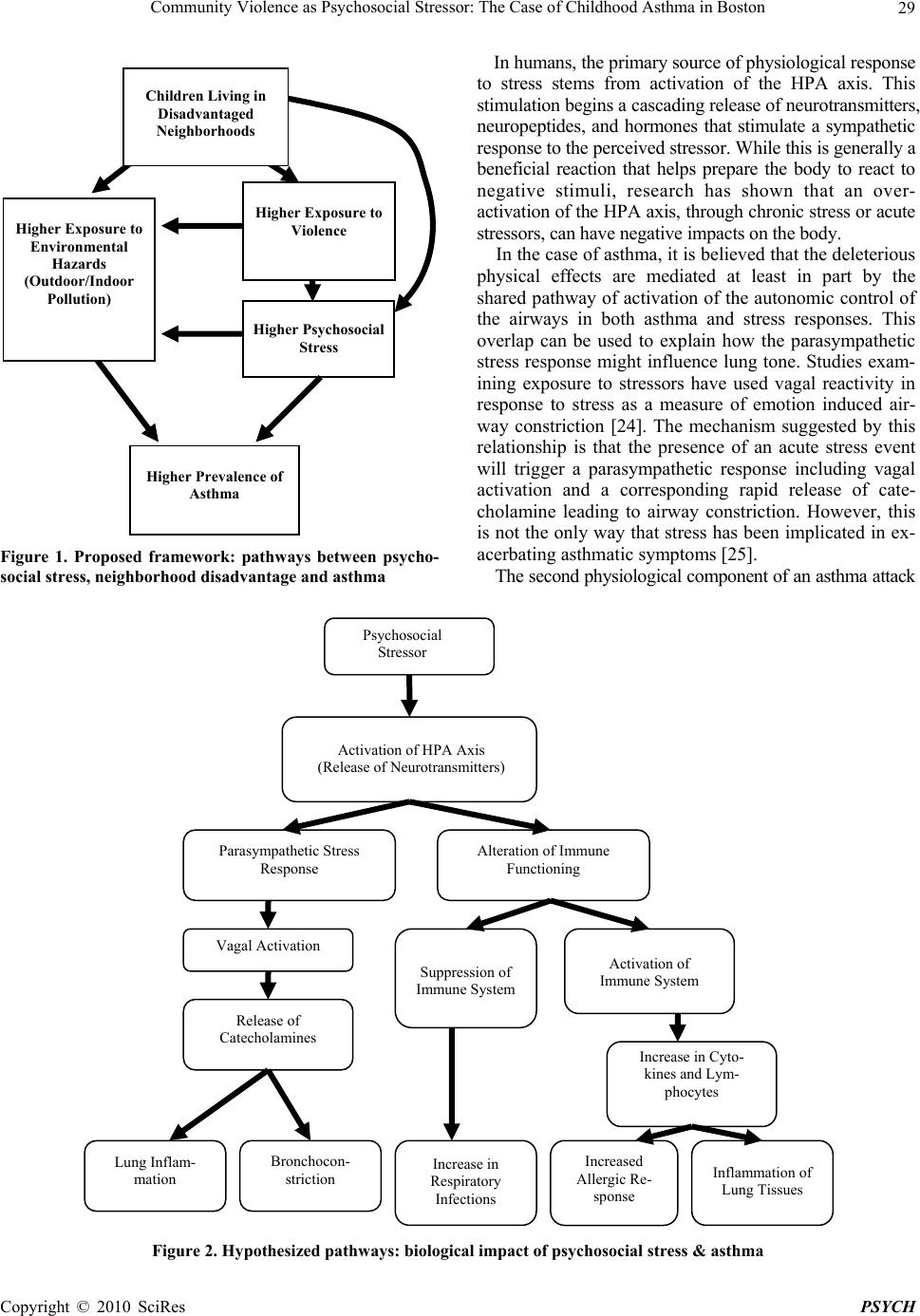

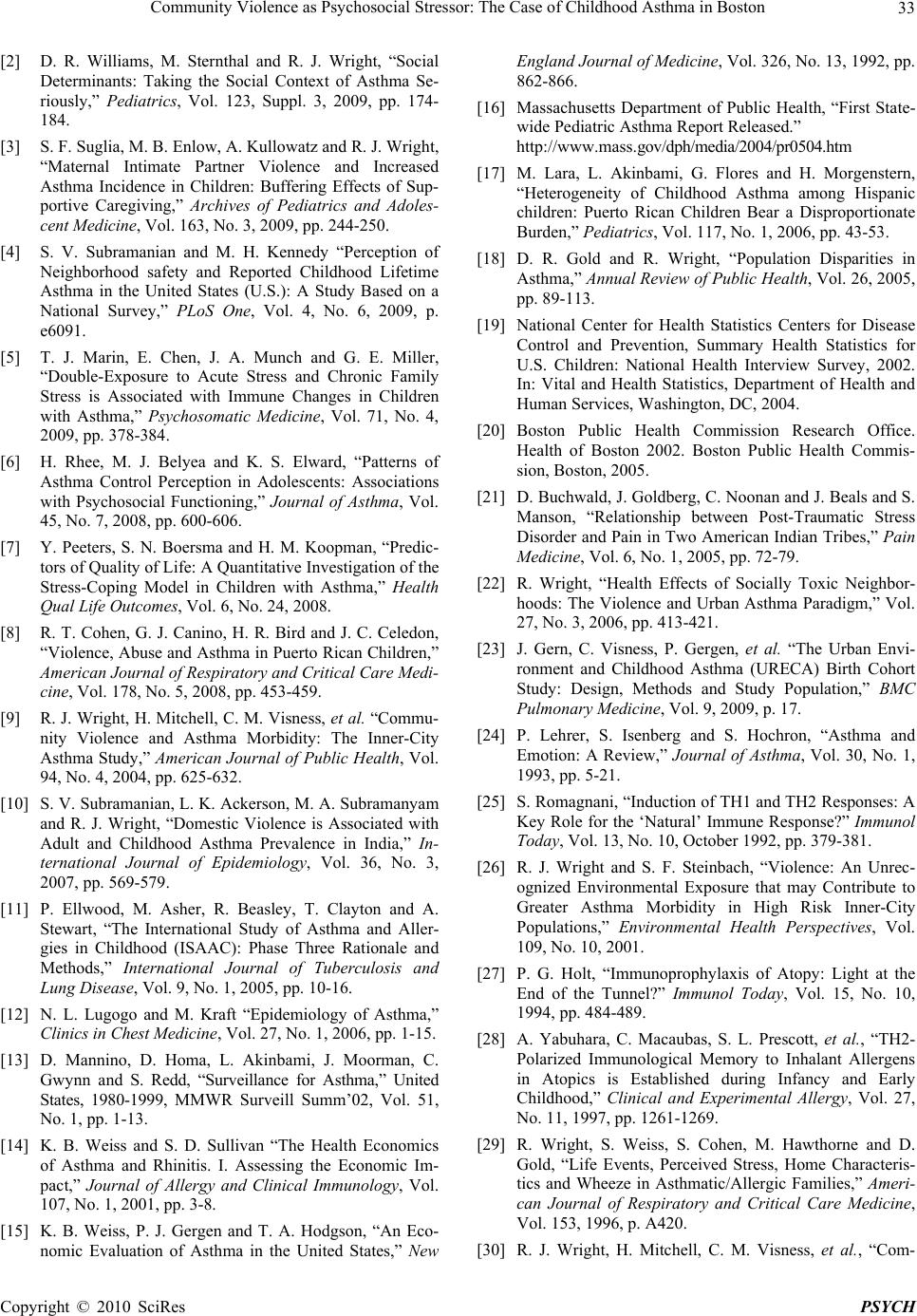

Psychology, 2010, 1: 27-34 doi:10.4236/psych.2010.11005 Published Online April 2010 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/psych) Copyright © 2010 SciRes PSYCH 27 Community Violence as Psychosocial Stressor: The Case of Childhood Asthma in Boston Gonzalo Bacigalupe1,2, Takeo Fujiwara3,4, Sabrina Selk3, Meghan Woo3 1Department of Counseling Psychology, University of Massachusetts Boston, Boston, USA; 2Department of Psychology, University of Deusto and Basque Foundation for Science, Ikerbasque, Bilbao, Spain; 3Department of Society and Human Development and Health, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, America; 4Department of Psychosocial Medicine, National Center for Child Health Development, Tokyo, Japan. Email: gonzalo.bacigalupe@umb.edu Received February 3rd, 2010; revised February 20th, 2010; accepted February 20th, 2010. ABSTRACT Childhood asthma is a critical public health p roblem of urban centers in the United S tates and other industrialized na - tions. Population-based and laboratory research studies indicate that psychosocial stress differentially affects asthma expression. Witnessing or experiencing community violence is a psychosocial stressor that results in long-term biologi- cal changes that may in turn contribute to asthma morbidity. This is a review of the literature that examines the expo- sure to violence as a psychosocial stressor that is independently associated with asthma morbidity even after adjust- ment for income, housing, and other adverse life events. In addition to acting as a physiological trigger for the disease, community violence can also impact health behaviors and exposure to other unknown environmental risk factors. This connection leads the authors to suggest that reducing violence and the amelioration of its impact has implications be- yond public health. Th e City of Boston in Massachusetts serves as the context to contextualize a series of recommenda- tions that may ameliorate and/or prevent asthma incidence and prevalence. The reduction of poverty, unemployment, substandard hous ing, and high crime/violence rates can ha ve significant health implicatio ns for children asthma and a decline on asthma hospitaliza tion. Keywords: Psychosocial Stress, Violence, Asthma, Public Health 1. Introduction Our current understanding of what causes asthma con- tinues to remain elusive [1]. There is, however, an in- creasing recognition of the relationship between psycho- social stress and asthma incidence and prevalence. We examine, first, this relationship, more specifically social violence, as a primary environmental exposure for asthma morbidity. And second, we discuss policy changes that may prevent and ameliorate asthma prevalence in urban settings including directions for future research. Child- hood asthma is the subject of innumerous research stud- ies. However, there are still many unknowns about its etiology and how environmental factors contribute to the onset and periodic episodes of this disease. Epidemiol- ogical research, meanwhile, demonstrates a dispropor- tionate burden of disease amongst children of low socio- economic position [2-8]. Furthermore, specific environ- mental exposures, such as violence, affect susceptible populations and contribute to asthmatic attacks [8-10]. This growing body of evidence, although still prelimi- nary, provides an alternative explanation through which psychosocial stress as a result of exposure to violence, acts as a primary exposure to elicit asthma symptoms. Research into this phenomenon may help to explain the higher burden of disease amongst children living in dis- advantaged neighborhoods and provide insight into in- terventions to combat this growing trend. 2. Epidemiology of Asthma 2.1 Burden of Asthma Childhood asthma is prevalent in all major urban centers in the United States and other industrialized nations [1,11]. In 2003, 30 million or 10.4% of Americans had asthma. 20 million had had an asthma attack in the previous year. 9 million or 12.5% of children under t he age of 18 in the U.S. had an asthma attack in the previous year. Current trends indicate that prevalence rates for current asthma increased more than double from 1980 to 2003. The most substantial increase occurred among children ages 0 to 4 years and ages 5 to 14 years. This increasing trend in rates was evident across race, sex, and age [12].  Community Violence as Psychosocial Stressor: The Case of Childhood Asthma in Boston Copyright © 2010 SciRes PSYCH 28 The medical services used to treat a sthma result in over 10.8 million physician visits, over 478,000 hospitalizations, 2 million emergency room visits, and about 28 million missed school days annually [13]. Direct health care ex- penditures such as physician visits, medications and other interventions are estimated to be US$ 7.4 billion. About US$ 3.2 billion of those direct costs are spent on asthma care for children [14]. Indirect costs such as decreased worker productivity, days lost from work by adults who have asthma or care for children with asthma, and other losses are an estimated $ 5.3 billion [15]. In Massachusetts, the first pediatric asthma surveil- lance report released in 2004 found that has 9.2% of children in school diagnosed with asthma. District level prevalence varies from 2.7 to 16.2%, with prevalence as high as 30 % in some schools [16]. This implies asthma prevalence correlates with district level factors such as physical or social environment. The Prevalence of active asthma in the city of Boston was higher than the Massa- chusetts average: one in seven, or 14% of children at- tending school had active asthma the year 2004 with a disproportionate burden of disease amongst students liv- ing in disadvantaged neighborhoods. Children with asthma average three times as many absences and use significantly more health services than o ther children. An estimated US$ 77 million a year are spent for both direct and indirect costs associated with childhood asthma in Massachusetts [16]. 2.2 Children in Disadvantaged Neighborhoods: A Vulnerable Population Asthma prevalence and morbidity rates have drastically risen in the United States over the past two decades. Children living in disadvantaged neighborhoods have been found to be particularly vulnerable to higher asthma morbidity rates. Neighborhood disadvantage is charac- terized by the presence of a number of community-level stressors including poverty, underemployment, racial discrimination, environmental inequity, limited social capital, sub-standard housing, high crime and violence rates [9]. Racial and income disparities in asthma mor- bidity have been consistently reported with higher rates of asthma hospitalization an d mortality in neighborhoods with low median incomes and a high prevalence of mi- nority populations [17]. The health problems of these disadvantaged populations are not likely to be solved without understanding the potential role of such social determinants of health [18]. In the United States today, rates of asthma morbidity are highest among minority children, particularly those who reside in urban areas of low socioeconomic pos ition. Income and poverty status has been found to be highly related to the number of asthma attacks a child reported in the last 12 months. 5.5% of children who were not poor reported having an asthma attack in the last 12- months compared to 8.0% of poor children [19]. In Bos- ton, childhood asthma morbidity rates are also highest in disadvantaged neighborhoods with a high percent of black and Latino residents and low socioeconomic status [20]. In contrast, neighborhoods with higher median in- come had much lower rates of hospitalization. 3. Psychosocial Stress: An Environmental Exposure 3.1 Psychosocial Stress and Asthma Most research attributes differences in asthma morbidity to variation in socioeconomic position. Disparities in asthma outcomes, however, cannot be explained by so- cioeconomic factors alone. Geographic variation has been found in asthma morbidity among cities and neighborhoods of similar socioeconomic status [9]. Growing evidence from population-based and laboratory studies indicate exposure to psychosocial stress differen- tially affects asthma expression [21]. These findings sug- gest that exposure to psychosocial stress puts children at greater susceptibility to asthma morbidity by disturbing the regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) system. In this framework, psychosocial stress can be conceptualized as an environmental exposure that can enter the body resulting in long-term biological changes that may contribute to asthma morbidity [22]. Research shows that psychosocial stress can also ex- acerbate asthma symptoms by making the lungs more susceptible to other environmental hazards. For instance, a lowered immune response caused by stress has been shown to increase rates of respiratory infections [23]. Stress can also influence behaviors which may lead to an increase in a child’s exposure to potential risks such as indoor allergens and second-hand smoke, or by making children more vulnopin (Figure 1). Researchers are just beginning to tease out these intertwining pathways. The following section presents the current state of research and the known biological impact of psychosocial stress on asthma morbidity including violence. 3.2 The Biological Impact of Psychosocial Stress The idea that emotions are important to asthma exacerba- tion is not new. References to this hypothesized connec- tion in popular culture and the scientific literature are common. However, it is only in recent years that scien- tists have been able to identify and to rigorously test theories of how exogenous events are translated into physiological responses. In this case, how psychosocial stress can lead to an asthma attack. Current research is examining the ways that psychosocial stress acts as a social pollutant that can increase morbidity and exacer- bate symptoms in children with asthma—a heuristic mode for this pathway is shown in Figure 2.  Community Violence as Psychosocial Stressor: The Case of Childhood Asthma in Boston Copyright © 2010 SciRes PSYCH 29 Figure 1. Proposed framework: pathways between psycho- social stress, neighborhood disadvantage and asthma In humans, the primary source of physiological response to stress stems from activation of the HPA axis. This stimulation begins a cascading release of neurotransmitters, neuropeptides, and hormones that stimulate a sympathetic response to the perceived stressor. Whil e t his is generally a beneficial reaction that helps prepare the body to react to negative stimuli, research has shown that an over- activation of the HPA axis, through chronic stress or acute stressors, can have negative impacts on the body. In the case of asthma, it is believed that the deleterious physical effects are mediated at least in part by the shared pathway of activation of th e autonomic control of the airways in both asthma and stress responses. This overlap can be used to explain how the parasympathetic stress response might influence lung tone. Studies exam- ining exposure to stressors have used vagal reactivity in response to stress as a measure of emotion induced air- way constriction [24]. The mechanism suggested by this relationship is that the presence of an acute stress event will trigger a parasympathetic response including vagal activation and a corresponding rapid release of cate- cholamine leading to airway constriction. However, this is not the only way that stress has been implicated in ex- acerbating asthmatic symptoms [25]. The second physiological co mponent of an asth ma attack Figure 2. Hypothesized pathways: biological impact of psychosocial stress & asthma Psychosocial Stressor Activation of HPA Axis (Release of Neurotransmitters) Parasympathetic Stress Response Alteration of Immune Functioning Vagal Activation Release of Catecholamines Lung Inflam- mation Bronchocon- striction Suppression of Immune System Increase in Respiratory Infections Activation of Immune System Increase in Cyto- kines and Lym- phocytes Increased Allergic Re- sponse Inflammation of Lung Tissues Higher Exposure to Environmental Hazards (Outdoor/Indoor Pollution) Higher Psychosocial Stress Higher Prevalence of Asthma Children Living in Disadvantaged Neighborhoods Higher Exposure to Violence  Community Violence as Psychosocial Stressor: The Case of Childhood Asthma in Boston Copyright © 2010 SciRes PSYCH 30 is believed to be more closely associated with immune function. Stress induced alterations in immune response can be complex and may include both activation and suppression of the immune system. Some suggest that this alteration in lymphocyte creation may be an impor- tant component to the etiology of asthma in children raised in stressful environments [26]. These immune al- terations are especially critical in the early development of a child’s immune system when the Th2 polarization of their immune system and Th2 reactivity to allergens de- velops [27,28]. Although the direct role of stress on Th2 levels is still being investigated, there is evidence that parental report of life stress is associated with onset of wheezing in children less than one year of age [29]. 3.3 Violence: A Primary Psychosocial Stressor Children living in disadvantaged neighborhoods are at higher risk for asthma morbidity largely resulting from greater exposure to psychosocial stressors. We have characterized psychosocial stress as an environmental exposure that directly impacts the physiological expres- sion of asthma. A clearer understanding of the most relevant sources of psychosocial stress that impact asth- ma morbidity is needed to adequately address interven- tions and policy initiativ es improving psychosocial stress exposure in this vulnerable population. The literature to date has primarily focused on exposure to community violence as the principal psychosocial factor impacting asthma morbidity among children living in disadvan- taged neighborhoods [9,26]. For the purposes of this pa- per we characterize community violence as direct expo- sure through victimization or through witnessing of vio- lence. We primarily refer to violence that occurs outside the home rather than domestic violence, although we acknowledge exposure to domestic violence could have similar effects on asthma morbidity. The psychosocial stressors associated with neighbor- hood disadvantage are numerous; however, the preva- lence of chronic community violence is a specific and extreme stressor confronting the urban poor [26]. Like- wise, the prevalence of high crime and violence is a critical component defining neighborhood disadvantage. As a result, exposure to violence has a direct impact on asthma morbidity rather than simply serving as a marker for low socioeconomic position. It has been independ- ently associated with asthma morbidity even after ad- justment for income, housing problems, and other ad- verse life events [30]. Certain populations face a greater deleterious effect of stress when facing daily life experiences that are unpre- dictable or uncontrollable [31]. This is critically impor- tant to asthma morbidity in disadvantaged neighb orhoods given that living in a violent community has been associ- ated with a chronic pervasive atmosphere of fear and the perceived threat of violence. Children and families ex- posed to community violence are more likely to view their world as being out of their control and to suffer more harmful effects from stress [26-30]. Community violence is pervasive. Studies have dem- onstrated that children living in urban disadvantaged neighborhoods are exposed to high rates of violence. More than 46% of children and adolescents in the U.S. reported being the direct victim of violence and over 60% reported having been exposed to community vio- lence [32]. In an inner-city cohort in Chicago, Ilinois, 42% of children ages 7-13 had seen someone shot while 37% had seen someone stabbed [33]. In Boston, one study examined the prevalence of witnessing violence among children ages 1-5 from the pediatric primary care clinic at Boston City Hospital. Th e res ear cher s fo und th at 10% of children witnessed a knifing or shooting; 18% witnessed shoving, kicking, or punching; and 47% heard gunshots [34]. Similarly, in a national cohort sample from large U.S. cities, children had a 2 fold increased risk of asthma when exposed to interpersonal vio lence at home [3]. 3.4 Impact of Exposure to Violence on Asthma Violence affects asthma morbidity through many path- ways. In addition to acting as a physiological trigger for the disease, community violence can also impact health behaviors and exposure to other unknown environmental risk factors [9]. For example, parents and caretakers who are worried about their children’s safety may re- strict outdoor activities leading to a greater exposure to indoor allergens. Given that the degree of housing dis- repair has been associated with increased cockroach allergen levels (a known risk factor for increased asthma), children who live in disadvantaged neighbor- hoods and must stay indoors have higher rates of asthma morbidity [35]. Keeping children indoors may also re- strict their ability to develop support networks. Addition- ally, it has been suggested that fear of crime fosters a distrust of others. Both of these factors can lead to social isolation and a diminishment of stress buffering factors such as social networks [26]. This exposure may also impact th e adoption of coping behaviors by household members such as smoking, an- other known trigger for asthma. One study examining increased rates of smoking in African American house- holds found that the strongest predictor of smoking was a report of high stress levels [36]. In a study of tobacco use among adolescents, smoking was strongly associated with adverse childhood experiences. This indicates nico- tine may be adopted as a pharmacological coping device for the negative emotional, neurobiological, and social effects of adverse childhood experiences [37]. Finally, a violent environment may also impact com- pliance to asthma treatments and medical follow-up. Caregivers may fear making a trip to a pharmacy or me-  Community Violence as Psychosocial Stressor: The Case of Childhood Asthma in Boston Copyright © 2010 SciRes PSYCH 31 dical provider for treatment due to fear of personal safety in a violent neighborhood. Additionally, pharmacies may not stay open at night in high crime areas, limiting im- mediate or emergency access to medication. As men- tioned previously it has been sugg ested that families who live in a violent environment are more likely to feel like their world is out of control. Helplessness has been linked to depression, which may limit the caretaker’s ability to buffer the detrimental effects of community violence in the lives of their children [38]. Caretakers living in violent communities frequently express a sense of helplessness and frustration in their inability to p rotect their children. 4. Policy Recommendations Prioritizing the reduction of psychosocial stressors, here described as community violence, in vulnerable neighbor- hoods introduces a ben eficial externality: th e reduction of asthma morbidity among children. This morbidity reduc- tion, in turn, would bring other forms of economic, social, and health benefits that are directly and indirectly related to the disease under study. In Boston and other urban settings, attempts at controlling violence have always been accompanied by large community initiatives. In conjunction with reducing psychosocial stress through violence prevention and control measures, making health care accessible is a core component in reducing other forms of psychosocial stress. Enhancing quality health care accessibility for children with asthma and reduction of known indoor environmental exposures are indispen- sable in the long-term control of asthma. Asthma morbidity is the result of a complex interplay of influences operating at several levels, including the individual, the family, and the community. Similarly, decisions regarding policies and programs that would reduce violence and the amelioration of its impact have implications beyond public health. Often policies that address violence prevention and control and health care access and quality operate in distinct legislative and regulatory worlds. To reformulate these policies into an integrated process, legislators should include psychoso- cial stressors like neighborhood violence in venues be- yond the realm of law enforcement. We recognize the complexity of preventing violence and asthma as well as the need for a variety of policies in the realm of environmental justice, human services, and law enforcement. However, none of these factors alone will suffice. For example, reinforcing police presence may not necessarily reduce the prevalence of psychoso- cial stress since police presence by itself may increase community stigma and fear. Our recommendations rec- ognize the need for intersectorial policies to simultane- ously address exposure to violence as well as prevention and treatment of asthma morbidity. There is strong evi- dence for violence acting as a significant psychosocial stressor however the exact mechanisms remain unclear introducing uncertainty in the risk analysis [39]. The pr e- cautionary principle [40] indicates that policy makers should develop the means to include considerations of the role that psychosocial stress plays on asthma morbid- ity within governmental and social policy as well as through recommendations to individuals [18]. We have categorized the recommendations under three areas: re- search and information, community participation, and public health initiatives. 4.1 Research & Information Exposure to violence as a risk to the health of children has been the source of a growing number of research initiatives. These are promising activities but more re- search is needed to assess the specific exposure pathway and its connection with the known factors that determine health and health care disparities in asthma morbidity. At the present, we are only able to hypothesize that violence acts as a compounding or additive mechanism in making children more vulnerable to the impact of environmental pollutants (indoor and outdoor)—likely through its im- pact on the health seeking behavior of parents and chil- dren under trea tment. In addition to more methodologically sound research to identify the morbidity mechanisms; there is also a need for greater data of asthma morbidity amongst chil- dren as well as information on trends over time. To fill this need, the City of Boston should be a leader in efforts to establish a centralized state asthma data registry. This registry should include a system of surv eillance by which psychosocial stressors assessment is routinely integrated into the treatment of children arriving with asth ma crises to emergency rooms and local community health centers. 4.2 Community Participation The City of Boston is experiencing resurgence in the number of homicides and other forms of social violence despite previous successful efforts at reducing its preva- lence. There is a rich opportunity to link the renewed efforts at preventing and controlling violence with an awareness and identification of the psychosocial stressors directly linked to asthma morbidity that offers a signifi- cant opportunity to strength en thos e efforts. These efforts may include: incorporating asthma morbidity prevention as another dimension in the Boston strategies to confront neighborhood violence, i.e., Boston Strategic Multi- Agency Response Teams, Youth Center Initiatives, among others [41]; creating collaborative research and interven- tion initiatives with housing collaborative health initia- tives to incorporate psychosocial stress as part of the surveillance and educational intervention activities en- gaging with community participants in the integration of evidence based knowledge into program efforts; incor-  Community Violence as Psychosocial Stressor: The Case of Childhood Asthma in Boston Copyright © 2010 SciRes PSYCH 32 porating the psychosocial stress agenda into the Asthma Planning Collaborative Initiative which has as a goal to develop a Massachusetts State Plan for Asthma. 4.3 Public Health Initiatives Asthma is one of many chronic diseases in the United States in which disparities in treatment and access to care have been documented [42]. The City of Boston as part of its plans which includ e redu cing h ealth disp arities [43] could provide further funding for: community based par- ticipatory research [44-46] with the goal of developing strategies to reduce violence in urban neighborhoods with high incidence of asthma morbidity; research pro- jects that use a positive dev iance model [47,48] to inves- tigate how some families and community groups have been able to develop effective strategies and positively cope despite the witnessing of social violence in their neighborhoods; curricular initiatives to develop educa- tional materials for others to learn from those community research experiences. Second, in addition to these community research ini- tiatives, the healthcare needs of patients need to be ad- dressed. Social violence inhibits the ability of parents of ensuring the safety of their children and leading to emo- tionally unavailability d ue to fear and trauma [49]. These healthcare needs could be satisfied via the development of a comprehensive program to support and empower parents as the key factor in developing resilience and mediate the effects of children’s exposure to violence; designing psych osocial and community interven tions that help parents to reduce the psychological strain produced by a sense of lack of control and agency in their lives; fostering the development of community cohesion and trust to provide parents with a social support network that counteracts the deleterious effects of social violence; collaborating with child welfare institutions and collabo- rative family initiatives to assess and strengthen appro- priate prevention and treatment of asthma morbidity among the children served by these programs; collecting information about asthma morbidity from programs that address the psychological needs of children that have identified as having witnessed or victimized by violence in their homes and/or neighborhoods. Third, universal health care coverage is synergetic with recommendations directly addressing health care access and quality in the case childhood asthma. As part of these efforts, medical insurers would include as part of their plans asthma medical supplies and education spe- cialists providing consistent education, expertise and support for patient to successfully identify and manage asthma; and, ameliorating the transportation and other health care access barriers. Examples of these efforts include a program like a roving clinic on wheels for asthmatic school children to provide a comprehensive asthma management strategy [50,51]. Policies that reduce poverty, unemployment, substan- dard housing, and high crime/violence rates may have significant health i mplications for child ren and ultimately have a direct impact on asthma hospitalization [2]. Simi- larly, policies that regulate outdoor and indoor air pollu- tion would also affect asthma morbidity. In addition to direct impacts on community residents, crime and vio- lence (or the lack thereof) can be used as indicators of collective well-being and social cohesion within a com- munity. Furthermore, the conditions known to be associ- ated with violence exposure are related to having ex- perienced stress [52,53], and chronic violence exposure has been conceptualized as a pervasive environmental stressor imposed on already vulnerable populations [4,10] including asthma [5,8]. 5. Conclusions Asthma is a highly prevalent and increasing health chal- lenge for urban neighborhoods across the nation and within Boston. Exposure to community violence creates high levels of psychosocial stress in neighborhoods, which are associated with a higher burden of childhood asthma. The theory of embodiment suggests that the body can often tell a story about the conditions of our lives [54,55]. We argue that asthma is the embodiment of the exposure to the environmental pollutant of violence in children’s lives. There are many pathways through which this experience acts upon the body. Lack of social support, fear and stigma, greater exposure to indoor pol- lutants and allergens, as well as impacts on health be- haviors are often part of living in environments where exposure to violence is high. However, it is violence it- self that acts as a primary predictor of the psychosocial stress that is translated into biological changes in the res- piratory and immune systems of children living in these neighborhoods. While there are uncertainties about the exact mechanisms behind this relationship, the precau- tionary principle should guide our actions towards mak- ing policies to protect the health of children now. Based on the evidence and the burden of disease, we analyzed potential interventions that include: continued research and data gathering; increasing community par- ticipation in measures to combat violence and revitalize neighborhoods; and initiation of public health programs to address both violence prevention and decreasing bar- riers to asthma care and treatment. True change in asthma morbidity can only o ccur when the full contex t in which children live their lives is considered, and this must include a realization of the important role that psy- chosocial stress and violence play in this disease. REFERENCES [1] M. I. Asher, “Recent Perspectives on Global Epidemiol- ogy of Asthma in Childhood,” Allergologia et Im- munopathologia, 2010.  Community Violence as Psychosocial Stressor: The Case of Childhood Asthma in Boston Copyright © 2010 SciRes PSYCH 33 [2] D. R. Williams, M. Sternthal and R. J. Wright, “Social Determinants: Taking the Social Context of Asthma Se- riously,” Pediatrics, Vol. 123, Suppl. 3, 2009, pp. 174- 184. [3] S. F. Suglia, M. B. Enlow, A. Kullowatz and R. J. Wright, “Maternal Intimate Partner Violence and Increased Asthma Incidence in Children: Buffering Effects of Sup- portive Caregiving,” Archives of Pediatrics and Adoles- cent Medicine, Vol. 163, No. 3, 2009, pp. 244-250. [4] S. V. Subramanian and M. H. Kennedy “Perception of Neighborhood safety and Reported Childhood Lifetime Asthma in the United States (U.S.): A Study Based on a National Survey,” PLoS One, Vol. 4, No. 6, 2009, p. e6091. [5] T. J. Marin, E. Chen, J. A. Munch and G. E. Miller, “Double-Exposure to Acute Stress and Chronic Family Stress is Associated with Immune Changes in Children with Asthma,” Psychosomatic Medicine, Vol. 71, No. 4, 2009, pp. 378-384. [6] H. Rhee, M. J. Belyea and K. S. Elward, “Patterns of Asthma Control Perception in Adolescents: Associations with Psychosocial Functioning,” Journal of Asthma, Vol. 45, No. 7, 2008, pp. 600-606. [7] Y. Peeters, S. N. Boersma and H. M. Koopman, “Predic- tors of Quality of Life: A Quantitative Investigation of the Stress-Coping Model in Children with Asthma,” Health Qual Life Outcomes, Vol. 6, No. 24, 2008. [8] R. T. Cohen, G. J. Canino, H. R. Bird and J. C. Celedon, “Violence, Abuse and Asthma in Puerto Rican Children,” American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medi- cine, Vol. 178, No. 5, 2008, pp. 453-459. [9] R. J. Wright, H. Mitchell, C. M. Visness, et al. “Commu- nity Violence and Asthma Morbidity: The Inner-City Asthma Study,” American Journal of Public Health, Vol. 94, No. 4, 2004, pp. 625-632. [10] S. V. Subramanian, L. K. Ackerson, M. A. Subramanyam and R. J. Wright, “Domestic Violence is Associated with Adult and Childhood Asthma Prevalence in India,” In- ternational Journal of Epidemiology, Vol. 36, No. 3, 2007, pp. 569-579. [11] P. Ellwood, M. Asher, R. Beasley, T. Clayton and A. Stewart, “The International Study of Asthma and Aller- gies in Childhood (ISAAC): Phase Three Rationale and Methods,” International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, Vol. 9, No. 1, 2005, pp. 10-16. [12] N. L. Lugogo and M. Kraft “Epidemiology of Asthma,” Clinics in Chest Medicine, Vol. 27, No. 1, 2006, pp. 1-15. [13] D. Mannino, D. Homa, L. Akinbami, J. Moorman, C. Gwynn and S. Redd, “Surveillance for Asthma,” United States, 1980-1999, MMWR Surveill Summ’02, Vol. 51, No. 1, pp. 1-13. [14] K. B. Weiss and S. D. Sullivan “The Health Economics of Asthma and Rhinitis. I. Assessing the Economic Im- pact,” Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, Vol. 107, No. 1, 2001, pp. 3-8. [15] K. B. Weiss, P. J. Gergen and T. A. Hodgson, “An Eco- nomic Evaluation of Asthma in the United States,” New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 326, No. 13, 1992, pp. 862-866. [16] Massachusetts Department of Public Health, “First State- wide Pediatric Asthma Report Released.” http://www.mass.gov/dph/media/2004/pr0504.htm [17] M. Lara, L. Akinbami, G. Flores and H. Morgenstern, “Heterogeneity of Childhood Asthma among Hispanic children: Puerto Rican Children Bear a Disproportionate Burden,” Pediatrics, Vol. 117, No. 1, 2006, pp. 43-53. [18] D. R. Gold and R. Wright, “Population Disparities in Asthma,” Annual Review of Public Health, Vol. 26, 2005, pp. 89-113. [19] National Center for Health Statistics Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Summary Health Statistics for U.S. Children: National Health Interview Survey, 2002. In: Vital and Health Statistics, Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, DC, 2004. [20] Boston Public Health Commission Research Office. Health of Boston 2002. Boston Public Health Commis- sion, Boston, 2005. [21] D. Buchwald, J. Goldberg, C. Noonan and J. Beals and S. Manson, “Relationship between Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and Pain in Two American Indian Tribes,” Pain Medicine, Vol. 6, No. 1, 2005, pp. 72-79. [22] R. Wright, “Health Effects of Socially Toxic Neighbor- hoods: The Violence and Urban Asthma Paradigm,” Vol. 27, No. 3, 2006, pp. 413-421. [23] J. Gern, C. Visness, P. Gergen, et al. “The Urban Envi- ronment and Childhood Asthma (URECA) Birth Cohort Study: Design, Methods and Study Population,” BMC Pulmonary Medicine, Vol. 9, 2009, p. 17. [24] P. Lehrer, S. Isenberg and S. Hochron, “Asthma and Emotion: A Review,” Journal of Asthma, Vol. 30, No. 1, 1993, pp. 5-21. [25] S. Romagnani, “Induction of TH1 and TH2 Responses: A Key Role for the ‘Natural’ Immune Response?” Immunol Today, Vol. 13, No. 10, October 1992, pp. 379-381. [26] R. J. Wright and S. F. Steinbach, “Violence: An Unrec- ognized Environmental Exposure that may Contribute to Greater Asthma Morbidity in High Risk Inner-City Populations,” Environmental Health Perspectives, Vol. 109, No. 10, 2001. [27] P. G. Holt, “Immunoprophylaxis of Atopy: Light at the End of the Tunnel?” Immunol Today, Vol. 15, No. 10, 1994, pp. 484-489. [28] A. Yabuhara, C. Macaubas, S. L. Prescott, et al., “TH2- Polarized Immunological Memory to Inhalant Allergens in Atopics is Established during Infancy and Early Childhood,” Clinical and Experimental Allergy, Vol. 27, No. 11, 1997, pp. 1261-1269. [29] R. Wright, S. Weiss, S. Cohen, M. Hawthorne and D. Gold, “Life Events, Perceived Stress, Home Characteris- tics and Wheeze in Asthmatic/Allergic Families,” Ameri- can Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, Vol. 153, 1996, p. A420. [30] R. J. Wright, H. Mitchell, C. M. Visness, et al., “Com-  Community Violence as Psychosocial Stressor: The Case of Childhood Asthma in Boston Copyright © 2010 SciRes PSYCH 34 munity Violence and Asthma Morbidity: The Inner-City Asthma Study,” American Journal of Public Health, Vol. 94, No. 4, 2004, pp. 625-632. [31] T. Lindhorst, B. Beadnell, L. J. Jackson, K. Fieland and A. Lee, “Mediating Pathways Explaining Psychosocial Functioning and Revictimization as Sequelae of Parental Violence among Adolescent Mothers,” American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, Vol. 79, No. 2, 2009, pp. 181-190. [32] D. Finkelhor, H. Turner, R. Ormrod, S. Hamby and K. Kracke, “Children’s Exposure to Violence: A Compre- hensive National Survey,” Juvenile Justice Bulletin, 2009, pp. 1-10. [33] K. Sheehan, J. A. DiCara, S. LeBailly and K. K. Chr istof- fel, “Children’S Exposure to Violence in an Urban set- ting,” Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, Vol. 151, No. 5, 1997, pp. 502-504. [34] L. Taylor, B. Zuckerman, V. Harik and B. Groves, “Wit- nessing Violence by Young Children and Their Mothers,” International Journal of Occupational Medicine and En- vironmental, Vol. 15, No. 2, 1994, pp. 120-123. [35] R. J. Wright and S. F. Steinbach, “Violence: An Unrec- ognized Environmental Exposure that may Contribute to greater asthma morbidity in High Risk Inner-City Popu- laions,” Environmental Health Perspectives, Vol. 109, No. 10, 2001, pp. 1085-1089. [36] M. P. Jensen, J. A. Turner, J. M. Romano and P. Karoly, “Coping with Chronic Pain: A Critical Review of the Lit- erature,” Pain, Vol. 47, No. 3, 1991, pp. 249-283. [37] R. F. Anda, J. B. Croft, V. J. Felitti, et al., “Adverse Childhood Experiences and Smoking during Adolescence and Adulthood,” Journal of the American Medical Asso- ciation, Vol. 282, No. 17, 1999, pp. 1652-1658. [38] E. Aisenberg, “The Effects of Exposure to Community Violence upon Latina Mothers and Preschool Children,” Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 23, 2001, pp. 378-398. [39] H. Foster and J. Brooks-Gunn, “Toward a Stress Process Model of Children’S Exposure to Physical Family and Community Violence,” Clinical Child and Family Psy- chology Review, Vol. 12, No. 2, 2009, pp. 71-94. [40] N. A. Ashford, “Implementing the Precautionary Princi- ple: Incorporating Science, technology, fairness and ac- countability in Environmental, Health and Safety Deci- sions,” International Journal of Occupational Medicine & Environmental, Vol. 17, No. 1, 2004, pp. 59-67. [41] D. I. Sheppard and S. Bilchik, “Promising Strategies to Reduce Gun Violence: Report,” Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, Cosmos Corporation, Wash- ington, D.C., United States, 1999. [42] B. D. Smedley, A. Y. Stith and A. R. Nelson, “Institute of Medicine (U.S.). Committee on Understanding and Elimi- nating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Un- equal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Dispari- ties in Health Care,” National Academy Press, Washing- ton, D.C., 2003. [43] The Disparities Project, “Data Report: A Presentation and Analysis of Disparities in Boston,” Boston Public Health Commission, Boston, 2005. [44] M. Viswanathan, A. Ammerman, E. Eng, et al. “Commu- nity-Based Participatory Research: Assessing the Evi- dence,” Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, 2004. [45] R. D. Lasker and E. S. Weiss, “Broadening Participation in Community Problem Solving: A Multidisciplinary Model to Support Collaborative Practice and Research,” Journal of Urban Health, Vol. 80, No. 1, pp. 14-47, 2003, pp. 48-60. [46] P. J. Kelly, “Practical Suggestions for Community Inter- ventions Using Participatory Action Research,” Public Health Nursing, Vol. 22, No. 1, 2005, pp. 65-73. [47] K. Lapping, D. R. Marsh, J. Rosenbaum, et al. “The Posi- tive Deviance Approach: Challenges and Opportunities for the Future,” Food and Nutrition Bulletin, Vol. 23, No. 4, 2002, pp. 130-137. [48] D. R. Marsh and D. G. Schroeder, “The Positive Devi- ance Approach to Improve Health Outcomes: Experience and Evidence from the Field. Introduction,” Food and Nutrition Bulletin , Vol. 23, No. 4, 2002, pp. 5-8. [49] E. S. Tonorezos, P. N. Breysse, E. C. Matsui, et al. “Does Neighborhood Violence Lead to Depression among Care- givers of Children with Asthma?” Social Science and Medicine, Vol. 67, No. 1, 2008, pp. 31-37. [50] J. Krieger and D. L. Higgins, “Housing and Health: Time Again for Public Health Action,” American Journal of Public Health, Vol. 92, No. 5, 2002, pp. 758-768. [51] J. Krieger, “Home Visits for Asthma: We Cannot Afford to Wait Any Longer, ” Archives of Pediatrics and Adoles- cent Medicine, Vol. 163, No. 3, 2009, pp. 279-281. [52] J. D. Osofsky, “Children as Invisible Victims of Domestic and Community Violence,” In: G. W. Holden, R. Geffner, E. N. Jouriles, eds. “Children Exposed to Marital Vio- lence: Theory, Research and Applied Issues,” American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, 1998, pp. 95-117. [53] J. D. Osofsky, “The Effects of Exposure to Violence on Young Children,” American Psychologist, Vol.50, No. 9, 1995, pp. 782-788. [54] N. Krieger, “Embodiment: A Conceptual Glossary for Epidemiology,” Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, Vol. 59, No. 5, 2005, pp. 350-355. [55] N. Krieger and G. Davey Smith “Bodies Count and Body Counts: Social Epidemiology and Embodying Inequal- ity,” Epidemiologic Reviews, Vol. 26, 2004, pp. 92-103. |