Journal of Cancer Therapy

Vol.2 No.5(2011), Article ID:16618,7 pages DOI:10.4236/jct.2011.25095

Comparison of 4-Weekly vs 3-Weekly Gemcitabine as Adjuvant Chemotherapy Following Curative Resection for Biliary Tract Cancer: A Prospective Randomized Controlled Trial

![]()

1Department of Surgery, Graduate School of Medicine, Osaka University, Suita, Japan; 2Department of Surgery, National Hospital Organization, Osaka National Hospital, Osaka, Japan; 3Department of Surgery, Toyonaka Municipal Hospital, Toyonaka, Japan; 4Department of Surgery, Hyogo Prefectural Nishinomiya Hospital, Nishinomiya, Japan; 5Department of Surgery, Kansai Rosai Hospital, Amagasaki, Japan; 6Department of Surgery, Osaka Police Hospital, Osaka, Japan; 7Department of Surgery, Osaka Rosai Hospital, Sakai, Japan.

E-mail: *amiyamo@onh.go.jp

Received August 28th, 2011; revised September 30th, 2011; accepted October 15th, 2011.

Keywords: biliary tract cancer, adjuvant therapy, gemcitabine

ABSTRACT

Background: Surgery for biliary tract cancer, including pancreatoduodenectomy and major hepatectomy, is too aggressive and does not allow postoperative gemcitabine to be administered by the usual dosage protocol. We hypothesized that the feasibility of 3-weekly protocol (days 1 and 8, every 3 weeks) of adjuvant gemcitabine therapy may be superior to the usual 4-weekly protocol (days 1, 8, and 15 every 4 weeks). Method: We compared the outcomes of 6 cycles of the 4-weekly protocol and 9 cycles of the 3-weekly protocol in a prospective randomized setting. The primary endpoint was the completion rate, and the secondary endpoints were the adverse events and the recurrence-free survival rate. Results: Totally, 27 patients were enrolled. The protocol could be completed without any omittances and/or dose modifications in two patients (14%) of the 4-weekly protocol, and three patients (23%) of the 3-weekly protocol (p = 0.8099); grade 3/4 neutropenia occurred in almost all the remaining (70%) patients. The relative dose intensity was 72% in the 4-weekly protocol and 78% in the 3-weekly protocol. There was no significant difference in the recurrence-free survival rate. Conclusion: The 3-weekly protocol did not yield superior completion, adverse events or recurrence-free survival rates as compared to the 4-week protocol. Trial Registration: UMIN-CTR, UMIN000001020.

1. Introduction

The prognosis of biliary tract cancer (BTC) is still poor [1-6]. Although surgical treatment remains the only potentially curative treatment, the overall 5-year survival rate remains approximately 40% [6,7]. This uncommon cancer is not yet well-studied because of the complexity of its classification and surgical procedures, andthe high perioperative morbidity, including liver dysfunction and cholangitis. Therefore, no (neo-) adjuvant chemotherapy has been established for these patients [8]. On the other hand, a pooled analysis [9] and multicenter retrospective analysis [10] revealed the potential efficacy of gemcitabine for unresectable and recurrent BTC, and a prospective randomized study revealed the survival benefit of gemcitabine-based chemotherapy in these patients [11,12]. Moreover, this drug has been shown to have a good safety profile, with a low incidence of grade 3/4 toxicities [13].

Based on this background, gemcitabine was introduced for adjuvant therapy after curative resection of BTC. However, it is difficult in the clinical setting to continue the usual4-weekly protocol (1000 mg/m2 on days 1, 8 and 15 every 4 weeks) after BTC surgery. And, there have been several reports of gemcitabine-based adjuvant chemo therapy following major hepatic to mine for BTC or pancrea to duodenectomy for pancreatic cancer, which have suggested that dose modification is often necessary or that the usual 4-weekly protocol could not be, or was not applied [14-16]. Because of the morbidity, liver dysfunction, and low performance status (PS) after BTC surgery (major hepatectomy/pancreatoduodenectomy), it would seem difficult to complete the usual 4-weekly protocol, and frequent pauses during the adjuvant during therapy would be necessary.

For the above reasons, we hypothesized that postoperative gemcitabine therapy by the3-weekly protocol (1000 mg/m2 on days 1 and 8 every 3 weeks) might be more feasible and superior to the 4-weekly protocol, because it would allow more treatment pauses. In this study, we compared the completion rate between patients assigned to the 4-weekly and 3-weekly protocols, for the same planned total dosage (6 cycles for the 4-weekly protocol and 9 cycles for the 3-weekly protocol). Because no feasibility studies of adjuvant gemcitabine therapy have been reported yet for BTC, we also comparatively estimated the frequency and severity of adverse events and the treatment efficacy (recurrence-free survival) between the two protocols. This study was registered with the University Hospital Medical Information Network Clinical Trials Registry (UMIN-CTR, UMIN 000001020) in JAPAN.

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Endpoints

We designed this open, multicenter, randomized controlled trial to explore the feasibility and efficacy of adjuvant gemcitabine therapy for BTC. The trial was initiated by the Osaka University Biliary Tract Cancer Treatment Group (OBCG, affiliated to the Multicenter Clinical Study Group of Osaka), Department of Surgery, Graduate School of Medicine, Osaka University. The protocol was approved by the institutional review board a teach hospital, and written informed consent was obtained from each of the patients.

The primary end point was the completion rate of adjuvant therapy. As control, we employed the 4-weekly protocol of gemcitabine treatment, which was studied in the CONKO-001 study after similar surgeries for pancreatic cancer [15].

The secondary end points included the frequency and severity of adverse events, for the purpose of collecting data on adverse events associated with adjuvant therapy, and the recurrence-free survival.

We determined that alpha and beta errors were 10% and 20%, respectively, to explore the feasibility and efficacy. After calculation of the sample seize, we determined that a total of 40 patients would be required. The study was started in August 2007 and completed in March 2010.

2.2. Patient Selection

Patients with histologically confirmed BTC (extrahepatic bile duct cancer, gall bladder cancer, or cancer of the papilla of Vater, UICC-stage II to IV [17]), who underwent macroscopic complete resection and no other therapy than surgery, were eligible for the study, and adjuvant therapy was to be started from 4 to 12 weeks after the surgery. Other eligibility criteria included age ≥20 years, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) PS 0/1 [18], adequate hematological, liver and renal function (hemoglobin > 10 g/dl, leukocytes > 4000/µl, neutrophils > 2000/µl, platelets > 100,000/µl, serum transaminases < 4× the upper limit of normal (ULN), serum bilirubin < 2× ULN, andserum creatinine < ULN).

Patients were excluded if they had active interstitial pneumonia, severe edema, pregnancy, active infection, severe underlying disease (impaired cardiac function, active peptic ulcer, ileus, uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, etc.), severe allergy, severe mental disorders, or active another cancer.

2.3. Treatment and Dose Modification

Standard surgical procedures were used depending on BTC involvement. Eligible patients were randomly assigned by a computer-generated central randomization with stratification for institution and surgical procedure (pancrea to duodenectomy vs. others).

Patients assigned to the 4-weekly protocol received 6 cycles, with each cycle consisting of three weekly administrations of intravenous gemcitabine at 1000 mg/m2, followed by a1-week drug-free pause. Patients assigned to the 3-weekly protocol received 9 cycles, each cycleconsisting of two weekly administrations of gemcitabine, followed by a1-week drug-free pause.

The first administration in each cycle was started with adequate hematological, liver, and renal functions (leukocytes > 3000/µl or neutrophils > 1500/µl, platelets > 100,000/µl, serum transaminases < 5 × ULN, serum bilirubin < 3 × ULN, and serum creatinine < ULN). When the first administration of any cycle could not be started within 28 days, the patient was withdrawn from the study.

For the second or third administrations in each cycle, the following were set in addition to first administration criteria; leukocytes > 2000/µl or neutrophils > 1000/µl, and platelet > 70,000/µl. When the above-mentioned criteriawere not fulfilled, dose modification was necessary for the next administration, as follows: 1000 mg/m2 > 800 mg/m2 > 600 mg/m2 > withdrawal from the study. Omitted doses of gemcitabine were not replaced. During the study, neither anti-cancer therapies were allowed. Patients were withdrawn from the study for any of the following reason: disease recurrence, patient’s desire to discontinue, or unacceptable treatment toxicity

2.4. Assessments

Prior to enrollment in the study, all patient sunder went routine examinations and laboratory studies. Tumor assessments were performed on the chest X-ray and abdominal computed tomo graphic or magnetic resonance images, prior to the adjuvant therapy and every 3 months.

During the study, vitalsigns, laboratory studies, PS, and toxicities/adverse events were evaluated prior to each administration. Toxicities were graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE version 3.0).

The overall survival and recurrence-free survival rates were calculated by the Kaplan–Meiermethod, and the log-rank test was used for comparisons. Student’s t-test or chi-square test was used to compare any differences. P-values <0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance. All statistical analyses were performed using the StatView J-5.0 software (SAS, Cary, NC).

3. Results

3.1. Results

A total of 27 patients were recruited into the study from 13 centersinthe Kansai area, Japan. Recruitment was planned for ending in March 2010, and we analyzed the data at thistime to determine whether the study should be extended or not. There were no differences in the completion rate between the protocols, and we completed the study in 27 patients. The patients were randomized to the 4-weekly protocol (n = 14) and or the 3-weekly protocol (n = 13).The baseline characteristics of the eligible patients are shown in Table 1, and there were no statistically differences between the two protocols. All patients had adenocarcinoma, the majority had Stage IIB BTC, 15 (56%) underwent pancreatoduodenectomy, and 8 (30%) underwent major liver surgery. The median time from surgery to the start of chemotherapy was 62 days (24 - 86), with no significant difference between the protocols.

3.2. Treatment Delivery

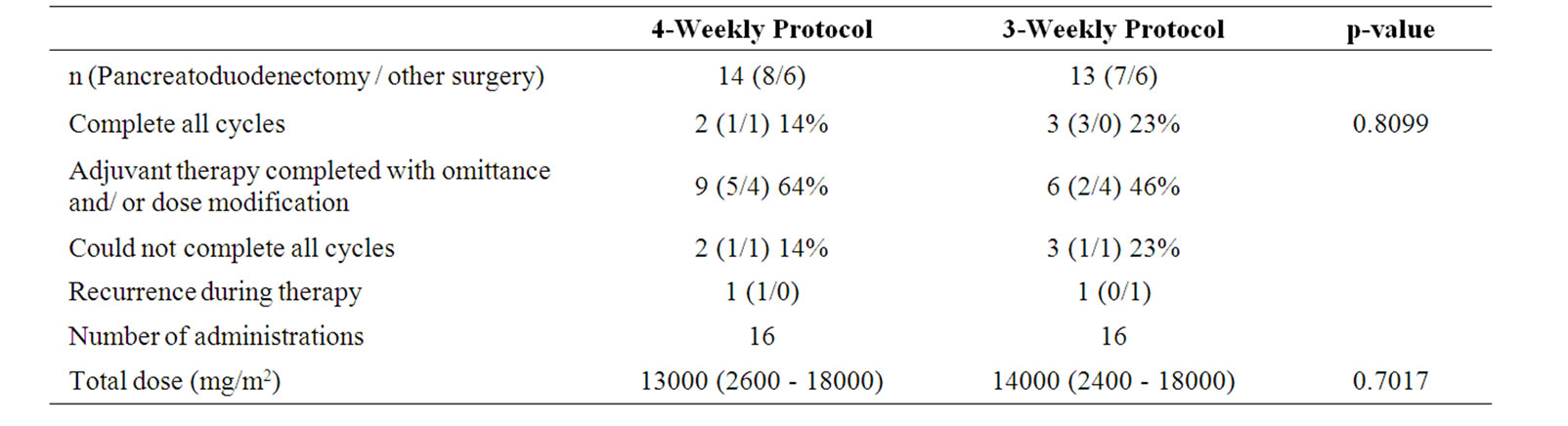

The number of patients in whom the adjuvant therapy could be completed without any omittances and/or dose modifications was 2 (14%) in the 4-weekly protocol and 2 (15%) in the 3-weekly protocol (p = 0.8099, Table 2). The scheduled treatment cycles could not be completed in 3 patients of the 4-weekly protocol and in 4 patients of the 3-weekly protocol. The median number of administrations was16 for both protocols, and the median durations of administration were 168 days and 189 days, depending on the protocol bias. The median total dosages of adjuvant gemcitabine were 13,000 mg/m2 in the 4- weekly protocol, and 14,000 mg/m2 in the 3-weekly protocol. The median relative dose intensities were 72.2% and 77.8%, respectively. The potential need for omittance on account of grade 3 hematological or other events occurred first at the 3rd administration in the 4-weekly protocol and at the 10th administration in the 3-weekly protocol.

Table 1. Patient characteristics.

In the subcategory analysis, the completion rates were 26.7% (4/15) and 9.0% (1/11) in pancreatoduodenectomy and other-surgery, respectively (p = 0.5691). The potential need for omittance occurred first at the 8th administration in pancreatoduodenectomy and at the 2nd administration in other-surgery. The dose intensities were 78% and 73%, respectively. In 4-weekly and 3-weekly protocol after pancreatoduodenectomy, the completion rates were 12.5% (1/8) and 42.9% (3/7), respectively (p = 0.5263). The potential need for omittance occurred first at the 3rd administration in the 4-weekly protocol, and at the 12th in the 3-weekly protocol (p = 0.0188). The dose intensities were 72% and 86%, respectively (p = 0.1152). After other-surgery, the completion rateswere 16.7% (1/6) and 0% (0/6), the potential need for omittance occurred first at the 3rd and 2nd administrations, and the dose intensities were 71% and 75%, respectively, in the 4-weekly and 3-weekly protocols, with no statistically significant differences between the two protocols.

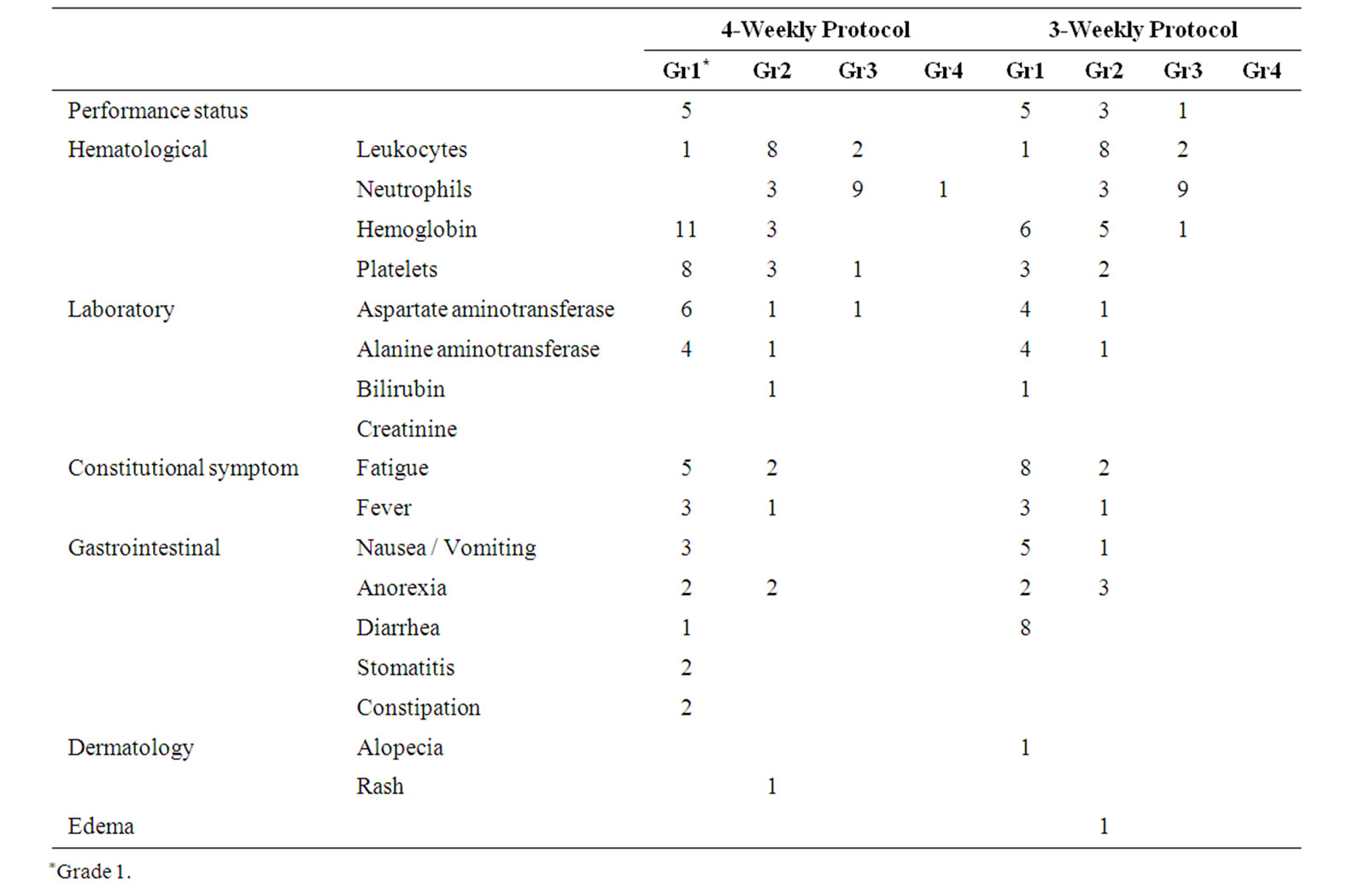

3.3. Toxicity

Grade 4 toxicities were encountered only in the 4-weekly protocol (grade 4 neutropenia), while grade 3 neutropenia was noted at a high frequency (64% and 69%, respectively) in both protocols (Table 3). Grade 3/4 nonhematologic toxicity occurred only infrequently in either

Table 2. Completion rate, number of administrations, and total dose.

Table 3. Number of patients with maximum grade of adverse events during the treatment.

protocol. A total of 27 serious adverse events (grade 3/4) were reported in the 21 patients (12 patients of the 4- weekly protocol and 9 patients of the 3-weekly protocol). In regard to the development of constitutional symptoms (PS and general fatigue) and gastrointestinal toxicity (nausea/vomiting), 52% and22% of patients developed grade 1/2 toxicities in the 4-weekly and 3-weekly protocolsandonly one patient experienced grade 3/4 toxicity (PS 3, just before withdrawal from the study).

3.4. Efficacy

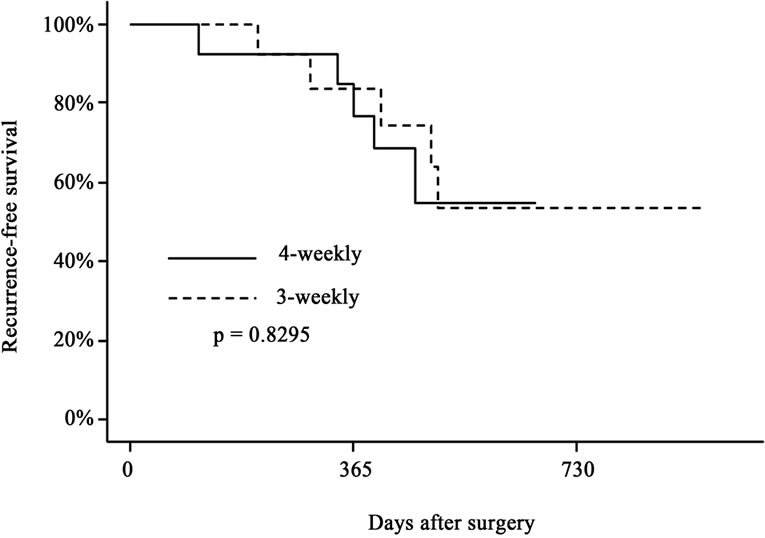

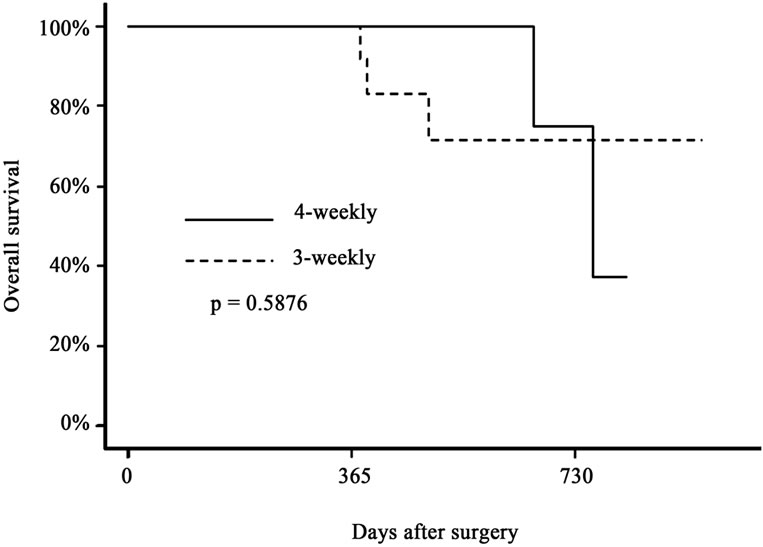

The survival curves are shown in Figure 1. For a median

(a)

(a) (b)

(b)

Figure 1. Recurrence-free survival (a) and overall survival (b) of biliary tract cancer patients after surgical resection. Solid line indicates the survival curve of the patients who received 6 cycles of adjuvant gemcitabine therapy by the 4-weekly protocol (1000 mg/m2 on days 1, 8 and 15 every 4 weeks), and the dotted line indicates that of those who received 9 cycles of adjuvant therapy by the 3-weekly protocol (1000 mg/m2 on days 1 and 8 every 3 weeks). There were no significant differences in either parameter between the two groups.

follow-up of 17 months, the 1- and 2-year recurrencefree survival rates were 77% and 55% in the 4-weekly protocol, and 84% and 53% in the 3-weekly protocol, respectively (p = 0.8295). The 1- and 2-year overall survival rates were 100% and 75% in the 4-weekly protocol, and 100% and 71% in the 3-weekly protocol, respectively (p = 0.5876).

4. Discussion

There is as yet no feasibility-certified adjuvant therapy for BTC, especially when gemcitabine is used. In pancrea to duodenectomy for pancreatic cancer, the CONKO- 001 and JSAP-02 trials revealed that dose modification was frequently necessary for completion [15,16]. In BTC, Murakami et al. presented gemcitabine-based adjuvant chemotherapy, however, all patients could not complete the protocol, even for biweekly 700 mg/m2 gemcitabinebased chemotherapy [14]. Clinically, several omittances are necessary in the usual 4-weekly protocol of gemcitabine after BTC surgery, and it become like the 3-weekly protocol. Therefore, we hypothesized that the 3-weekly protocol may be more feasible and superior (higher completion rate). However, the 3-weekly protocol was not superior to the 4-weekly protocol in the completion rate, frequency of adverse events, or disease-free survival. In other words, the administration protocol did not influence the completion rate of adjuvant gemcitabine therapy for BTC.

In regard to the relative dose intensity, approximately 75% was achieved on average. In CONKO-001 and JSAP-02 (Note; including distal pancreatectomy), the relative dose intensity was approximately 90% [15,16]. In our data, the dose intensity was 78% in pancreatoduodenectomy, but only 73% in other-surgery (including liver resection). It would therefore seem that the dose intensity is related to the surgical stress. On the other hand, the dose intensity in pancrea to duodenectomy treated by the 3-weekly protocol was 86%, whereas that in the subgroup treated by the 4-weekly protocol was approximately 70%. Similar data were obtained for the first drug omittance. In pancrea to duodenectomy, the first potential omittance was necessitated much later in the 3-weekly protocol than in the 4-weekly protocol, the difference being statistically significant. In other-surgery, the dose intensity was only 70% in both protocols and the first omittances were necessitated at the 2nd - 3rd administrations; these data were inferior to the data in the 3-weekly subgroup of pancrea to duodenectomy. In addition, some patients who underwent hepatectomy received only few gemcitabine administrations before withdrawal. This led us to speculate that in pancrea to duodenectomy, the 3-weekly protocol might be better, but that in more aggressive surgery, like major liver resection, neither the 4-weekly nor the 3-weekly protocol might be feasible for adjuvant therapy. This study might not have enough power to mention these speculations. It would be necessary to perform phase I study to yield a higher dose intensity, followed by phase II/III study in a larger study group.

In relation to treatment toxicity, we encountered a high frequency of grade 3/4 neutropenia, and also of grade 2 constitutional symptoms and gastrointestinal adverse events. Although there is little information about neutropenia in previous reports [14,15], the JSAP-02 reported a high frequency of grade 3/4 neutropenia [16], similar to our study. This adjuvant therapy seemed to yield a high frequency of not grade 3/4 leukopenia, but of grade 3/4 neutropenia. After surgery for BTC, the patients sometimes develop cholangitis, and with the occurrence of severe neutropenia, liver abscess and/or sepsis could occur. Patients must therefore be closely monitored for the development of neutropenia. In regard to constitutional symptoms and gastrointestinal adverse events, approximately 25% of the patients with such adverse events were unable to carry on with their work activities or needed drip infusions (grade 2 toxicity), suggesting that treatment of these patients in the outpatient setting might be difficult.

In regard to the efficacy, we compared our historical data [4-6] and the report from the Japanese Society of Biliary Surgery (JSBS) [7,19], and data on gemcitabinebased adjuvant therapy by Murakami et al. [14]. In regard to the recurrence-free survival, the data in our present study (77% - 84% at 1 year and 52% - 55% at 2 years) were similar to those reported by Murakami et al. (recurrence-free survival: 79% at 1 year and 60% at 3 years) [14]. In terms of overall survival, the rate in our study 75% - 71% at 2 years, as compared to historical data (without adjuvant therapy) of approximately 65% at 2 years and 60% - 63% at 3 years. The JSBS reported an overall survival rate of 40% - 65% at 3 years. Based on the above findings, we suggest that there remains the possibility of a survival benefit of adjuvant gemcitabine therapy after BTC surgery.

In conclusion, the 3-weekly gemcitabine treatment protocol was not superior to the 4-weekly protocol in terms of the completion rate, relative dose intensity, adverse events or recurrence-free survival, among patients receiving adjuvant therapy following BTC surgery; a high frequency of grade 3/4 neutropenia was found in both the protocols. Furthermore, the treatment could be completed without any interruptions and/or dose modifications in only approximately 10% of the patients. Our findings suggest the possibility of the dose intensity depending on the aggressiveness level of the surgical procedures, and further investigation is warranted. For a precise evaluation of the efficacy in a feasibility study for adjuvant therapy after aggressive BTC surgery, a prospective randomized study with a large number of patients would be necessary.

5. Disclosure

The authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

6. Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr Y. Sasaki,Yao Municipal Hospital, who served as the chief of the Independent Data Monitoring Committee.

Study sites and investigators (authors not included): Yushikazu Morimoto, Department of Surgery, Osaka Kouseinenkin Hospital; Terumasa Yamada, Department of Surgery, Osaka Medical Center for Cancer and Cardiovascular Diseases. Osakuni Morimoto, Department of Surgery, Ikeda Municipal Hospital, Tameyoshi Yamamoto, Department of Surgery, Sakai Municipal Hospital, Nariaki Fukuchi, Department of Surgery, Higashiosaka Municipal Hospital, and Takashi Deguchi, Departments of Surgery, Osaka General Medical Center.

REFERENCES

- National Cancer Center, “Cancer Statistics in Japan,” 2005. http://www.ncc.go.jp/en/statistics/index.html

- C. M. Haskelled, “Cancer Treatment,” 5th Edition, WBSaunders Co., Philadelphia, 2001.

- B. Levin, “Gallbladder Carcinoma,” Annals of Oncology, Vol. 10, No. 3, 1999, pp. 129-130. doi:10.1023/A:1008325911628

- S. Kobayashi, H. Nagano, S. Marubashi, Y. Takeda, M. Tanemura, K. Konishi, Y. Yoshioka, T. Inoue, Y. Doki and M. Mori, “Impact of Postoperative Irradiation after Non-Curative Resection of Hilar Biliary Cancer,” Journal of Surgical Oncology, Vol. 100, No. 8, 2009, pp. 657- 662. doi:10.1002/jso.21409

- S. Kobayashi, H. Nagano, S. Marubashi, H. Wada, H. Eguchi, Y. Takeda, M. Tanemura, Y. Doki and M. Mori, “Multi-Detector Computed Tomography for Preoperative Prediction of Postsurgical Prognosis of Patients with Extrahepatic Biliary Cancer,” Journal of Surgical Oncology, Vol. 101, No. 5, 2010, pp. 376-383.

- S. Kobayashi, H. Nagano, S. Marubashi, H. Wada, H. Eguchi, Y. Takeda, M. Tanemura, K. Umeshita, Y. Doki and M. Mori, “Treatment of Borderline Cases for Curative Resection of Biliary Tract Cancer,” Journal of Surgical Oncology, In Press.

- S. Miyakawa, S. Ishihara, A. Horiguchi, T. Takada, M. Miyazaki and T. Nagakawa, “Biliary Tract Cancer Treatment: 5584 Results from the Biliary Tract Cancer Statistics Registry from 1998 to 2004 in Japan,” Journal of HepatoBiliary-Pancreatic Surgery, Vol. 16, No. 1, 2009, pp. 1-7. doi:10.1007/s00534-008-0015-0

- J. Furuse, T. Takada, M. Miyazaki, S. Miyakawa, K. Tsukada, M. Nagino, S. Kondo, H. Saito, T. Tsuyuguchi, K. Hirata, F. Kimura, H. Yoshitomi, S. Nozawa, M. Yoshida, K. Wada, H. Amano and F. Miura, “Japanese Association of Biliary Surgery; Japanese Society of HepatoBiliary-Pancreatic Surgery; Japan Society of Clinical Oncology. Guidelines for chemotherapy of biliary tract and ampullary carcinomas,” Journal of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Surgery, Vol. 15, No. 1, 2008, pp. 55-62. doi:10.1007/s00534-007-1280-z

- F. Eckel and R. M. Schmid, “Chemotherapy in Advanced Biliary Tract Carcinoma: A Pooled Analysis of Clinical Trials,” British Journal of Cancer, Vol. 96, No. 6, 2007, pp. 896-902. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6603648

- N. Yonemoto, J. Furuse, T. Okusaka, K. Yamao, A. Funakoshi, S. Ohkawa, N. Boku, K. Tanaka, M. Nagase, H. Saisho and T Sato, “A Multi-Center Retrospective Analysis of Survival Benefits of Chemotherapy for Unresectable Biliary Tract Cancer,” Japanese Journal of Clinical Oncology, Vol. 37, No. 11, 2007, pp. 843-851. doi:10.1093/jjco/hym116

- J. W. Valle, H. Wasan, P. Johnson, E. Jones, L. Dixon, R. Swindell, S. Baka, A. Maraveyas, P. Corrie, S. Falk, S. Gollins, F. Lofts, L. Evans, T. Meyer, A. Anthoney, T. Iveson, M. Highley, R. Osborne and J. Bridgewater, “Gemcitabine Alone or in Combination with Cisplatin in Patients with Advanced or Metastatic Cholangiocarcinomas or Other Biliary Tract Tumours: A Multicentre Randomised Phase II Study—The UK ABC-01 Study,” British Journal of Cancer, Vol. 101, No. 4, 2009, pp. 621-527. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6605211

- J. Valle, H. Wasan, D. H. Palmer, D. Cunningham, A. Anthoney, A. Maraveyas, S. Madhusudan, T. Iveson, S. Hughes, S. P. Pereira, M. Roughton and J. Bridgewater, “ABC-02 Trial Investigators.Cisplatin Plus Gemcitabine versus Gemcitabine for Biliary Tract Cancer,” New England Journalof Medicine, Vol. 362, No. 14, 2010, pp. 1273-1281. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0908721

- M. S. Aapro, C. Martin and S. Hatty, “Gemcitabine—a Safety Review,” Anticancer Drugs, Vol. 9, No. 3, 1998, pp. 191-201. doi:10.1097/00001813-199803000-00001

- Y. Murakami, K. Uemura, T. Sudo, Y. Hayashidani, Y. Hashimoto, H. Nakamura, A. Nakashima and T. Sueda, “Adjuvant Gemcitabine Plus S-1 Chemotherapy Improves Survival after Aggressive Surgical Resection for Advanced Biliary Carcinoma,” Annals of Surgery, Vol. 250, No. 6, 2009, pp. 950-956. doi:10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b0fc8b

- H. Oettle, S. Post, P. Neuhaus, K. Gellert, J. Langrehr, K. Ridwelski, H. Schramm, J. Fahlke, C. Zuelke, C. Burkart, K. Gutberlet, E. Kettner, H. Schmalenberg, K. WeigangKoehler, W. O. Bechstein, M. Niedergethmann, I. SchmidtWolf, L. Roll, B. Doerken and H. Riess, “Adjuvant Chemotherapy with Gemcitabine vs. Observation in Patients Undergoing Curative-Intent Resection of Pancreatic Cancer: A Randomized Controlled Trial,” Journal of the American Medical Association, Vol. 297, No. 3, 2007, pp. 267-277. doi:10.1001/jama.297.3.267

- H. Ueno, T. Kosuge, Y. Matsuyama, J. Yamamoto, A. Nakao, S. Egawa, R. Doi, M. Monden, T. Hatori, M. Tanaka, M. Shimada and K. Kanemitsu, “A Randomised Phase III Trial Comparing Gemcitabine with SurgeryOnly in Patients with Resected Pancreatic Cancer: Japanese Study Group of Adjuvant Therapy for Pancreatic Cancer,” British Journal of Cancer, Vol. 101, No. 6, 2009, pp. 908-915. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6605256

- L. H. Sobin and C. Wittekind, “International Union Against Cancer, TNM Classification of Malignant Tumors,” 6th Edition, Wiley-Liss, New York, 2002.

- M. M. Oken, R. H. Creech, D. C. Tormey, J. Horton, T. E. Davis, E. T. McFadden and P. P. Carbone, “Toxicity and Response Criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group,” American Journal of Clinical Oncology, Vol. 5, No. 6, 1982, pp. 649-655. doi:10.1097/00000421-198212000-00014

- “Japanese Society of Biliary Surgery: Classification of Biliary Tract Carcinoma,” 5th Edition, Kanehara, 2003.