Health

Vol.5 No.11(2013), Article ID:39723,8 pages DOI:10.4236/health.2013.511249

Knowledge of child nutrition when breastfeeding—A study of mothers living outside Hanoi*

![]()

1Midwifery Department, Faculty of Nursing, Hanoi Medical University, Hanoi, Vietnam 2School of Health Sciences, Jönköping University, Jönköping, Sweden; #Corresponding Author: Ann.B.Bengtson@gmail.com

3Institute of Health and Care Sciences, Sahlgrenska Academy at the University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden

Copyright © 2013 Thi Thu Huong Nguyen et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received 29 August 2013; revised 5 October 2013; accepted 25 October 2013

Keywords: Breastfeeding; Malnutrition; Nutrition Education; Supplementary Food

ABSTRACT

Objective: To evaluate the knowledge of nutriation among mothers of children less than two years of age and changes in theoretical knowledge after a nutrition course. Method: A pilot study with a pre-post-test design. Thirty mothers of children who were less than two years of age from outside Hanoi participated in the study. The mothers’ knowledge of breastfeeding, supplementary food and diet when the child was suffering from diarrhea was collected using 19 self-reported questions. A one-day nutrition course at which the mothers answered the same questions before and after the course was run. Results: All the invited mothers were included in the study. There was a lack of knowledge about breastfeeding and nutrition at baseline, but it improved after the nutrition course. The greatest improvement in knowledge related to breastfeeding less than 30 minutes after delivery, not giving milk or fruit juice instead of breast milk, increasing the frequency of breastfeeding in the event of a smaller amount of milk and knowledge about giving supplementary food after six months. Moreover, the results revealed that the mothers reported better knowledge of the consumption and frequency of more healthy food supplements. Conclusion: There was a lack of knowledge about nutrition among the mothers with children less than two years of age. The course demonstrated effectiveness in every aspect of nutritional knowledge, tested in the posttest. The findings in this study could provide important information for authorities in the health sector to improve the nutritional state of children in the community.

1. INTRODUCTION

In the developing countries, and in southern Asia in particular, malnutrition is a major health burden. At global level, it is the most important risk factor for illness and death and about 50 percent of all deaths are associated with malnutrition, where young children in particular are affected [1]. In South-east Asia in 2001, underweight accounted for 30% in children under five years of age, starvation for 10% and stunting 33%, reflecting the result of prolonged poor health and lack of food [2]. The determinants of malnutrition are multifactorial, where poverty-related factors, such as economy, educational and sanitation level, climate, food-related norms, as well as food production, breastfeeding habits and access to the health service, are influential factors [1]. To reduce malnutrition at an early age, the WHO recommends breastfeeding for about six months, followed by continued breastfeeding and, as an important addition, the introduction of supplements to the regular diet [3,4]. Many countries and organisations have implemented projects to prevent malnutrition in children and Vietnam is no exception [5-7].

Since the implementation of the government’s original policy, the economic situation in Vietnam has developed significantly and the standard of living has therefore improved. However, there is a significant difference in different areas and age groups [8]. Recent studies from Vietnam showed that 19.7% - 27.7% of children under three years of age were underweight, 23.4% - 36% were stunted and 5.3% - 10.2% were wasting. This confirms that a healthy nutritional status for children in Vietnam has not yet been achieved and the nutritional status differs in areas within the country [9,10].

Protein energy malnutrition usually manifests itself at an early stage, in children between six months and two years of age, and it is associated with early weaning, the delayed introduction of complementary foods, a lowprotein diet and severe or frequent infections [11]. Even if mothers breastfeed for the first month, only 50% continue for the first six months. Moreover, fewer mothers begin breastfeeding within 30 minutes after delivery. Studies have found a significant negative relationship between parental breastfeeding classes and breastfeeding in practice [12], but they also reveal that the prevalence of undernutrition increases with age [9]. In spite of this, several studies have demonstrated the importance of parental breastfeeding education in the developing countries [9,10,12,13].

The malnutrition prevention strategy stresses that, during the first two years, children should be targeted. The sooner malnutrition begins during this period, the more serious it will be. Recent studies have shown that nutrition intervention during the early period helps to produce the maximum impact on growth, which also increases the potential for improved health [6,9].

In the first two years, children run a high risk of suffering from infectious diseases, especially diarrhea or respiratory diseases, which are closely related to malnutrition. Children with malnutrition have difficulty recovering from these diseases. For this reason, preventing malnutrition in this high-risk period and in high-risk areas must be stressed and paid a great deal of attention [14].

In reality, it is known that malnutrition in children is not only the result of a lack of food or health care and hygiene in the environment but also the result of a lack of knowledge of nutrition and the time mothers spend caring for their children. In many families with a high income, mothers do not know how to care for their children properly and they have a poor knowledge of nutriation and food behaviours which may affect malnutrition [15,16].

The mothers of young children, i.e. under two years of age, play an important role in child care and this is often dependent on the mothers’ educational background and living habits [10]. In Vietnam, children are breastfed or bottle-fed in the first two years. After that, they usually start with other non-nutritious food before having the same meals as other members of their family. For this reason, improving the mothers’ knowledge of nutrition for their children, their children’s care and development will bring about improvements in terms of mental and physical health. In order to develop strategies for increasing mothers’ knowledge of nutrition for their children, it is important to describe the current state of knowledge in different areas in Vietnam and to find effective methods for increasing this knowledge in specific groups.

Aim

The aim of this pilot study was to describe the knowledge of nutrition among mothers of children less than two years of age in a rural area outside Hanoi. Moreover, an additional aim was to analyse whether there were any changes in self-reported knowledge after a one-day nutrition course.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study Population

The study was carried out in a small municipality outside Hanoi with 10,137 inhabitants, in which most of the inhabitants are farmers specialising in cultivating water rice. The municipality is situated 10 km from the District Health Station and has one health station with seven health workers, one of whom is a physician. The municipality also includes seven hamlets with seven nutriation workers.

The study population comprised mothers with one child less than two years of age who were living in the target community at the time of data collection. The children were born between March 2006 and March 2008. Moreover, the inclusion criteria were also that the mothers were able to speak and understand Vietnamese, and that they had no obvious physical, mental or cognitive impairment a fulfilled the nutrition course.

2.2. Sampling Method

A list of the names of mothers who met the inclusion criteria was obtained from the municipal health station. According to the data from the national immunisation programme relating to the children in seven hamlets in the municipality, more than 300 children less than two years of age met the criteria for sampling. From this group, a systematically randomised sample was used in which every tenth mother of these children was chosen and asked to participate in the study. Finally, 30 mothers aged from 18 - 40 were included.

An invitation letter was sent to all mothers. The mothers were given both verbal information and a written information letter. The mothers signed an informed consent before the study was started. The author stayed at the municipal health station to invite the mothers to participate in the study. All the included mothers agreed to participate in the study.

2.3. Questionnaire and Nutrition Course

The questionnaire included 19 questions relating to knowledge about breastfeeding, supplementary food and knowledge of diet when a child suffers from diarrhea. There were also questions about the mothers’ age, education and occupation and the children’s age, gender and weight at birth. The researcher helped the mothers to fill in the questionnaires. The nutrition questionnaire was answered before and two weeks after the nutrition course.

All 30 mothers attended a one-day course on nutrition including information about the importance of breastfeeding and the healthy benefits with breast milk. The teaching material included handouts, pictures, blackboard and chalk. The lecture was presented in a room at the municipal health station where the ventilation was good and there were enough seats for all the participants. The room was quite large, so the mothers could move about to discuss or write on the board. Both the course and the questions were based on national guidelines from the Ministry of Health in Vietnam and Hanoi Medical University regarding nutrition and safety food [17,18].

2.4. Ethical Considerations

The study was approved by the head of the Mai Lam municipality. Accepted rules from the National Pediatric Hospital, Ha Noi, Vietnam, relating to an ethical review of the study design and the Helsinki Declaration [19], were followed. Participation was voluntary after informed consent. All the participants were able to leave this study without any legal responsibility. All information about subjects was kept confidential.

2.5. Data Analysis

The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 11.5 for Windows was used to analyse the data collected in this study. Prior to analysing the data, all the variables were examined using various SPSS programs to check the accuracy of data entry and missing values. First, frequencies and percentages were calculated for each of the variables and the data were then verified.

In order to investigate the relationship for nutritional knowledge between pre-test and post-test, Student’s ttest (mother’s age, infant’s age and so on) and χ2 tests for categorical variables (maternal education and baby’s gender) were used.

3. RESULTS

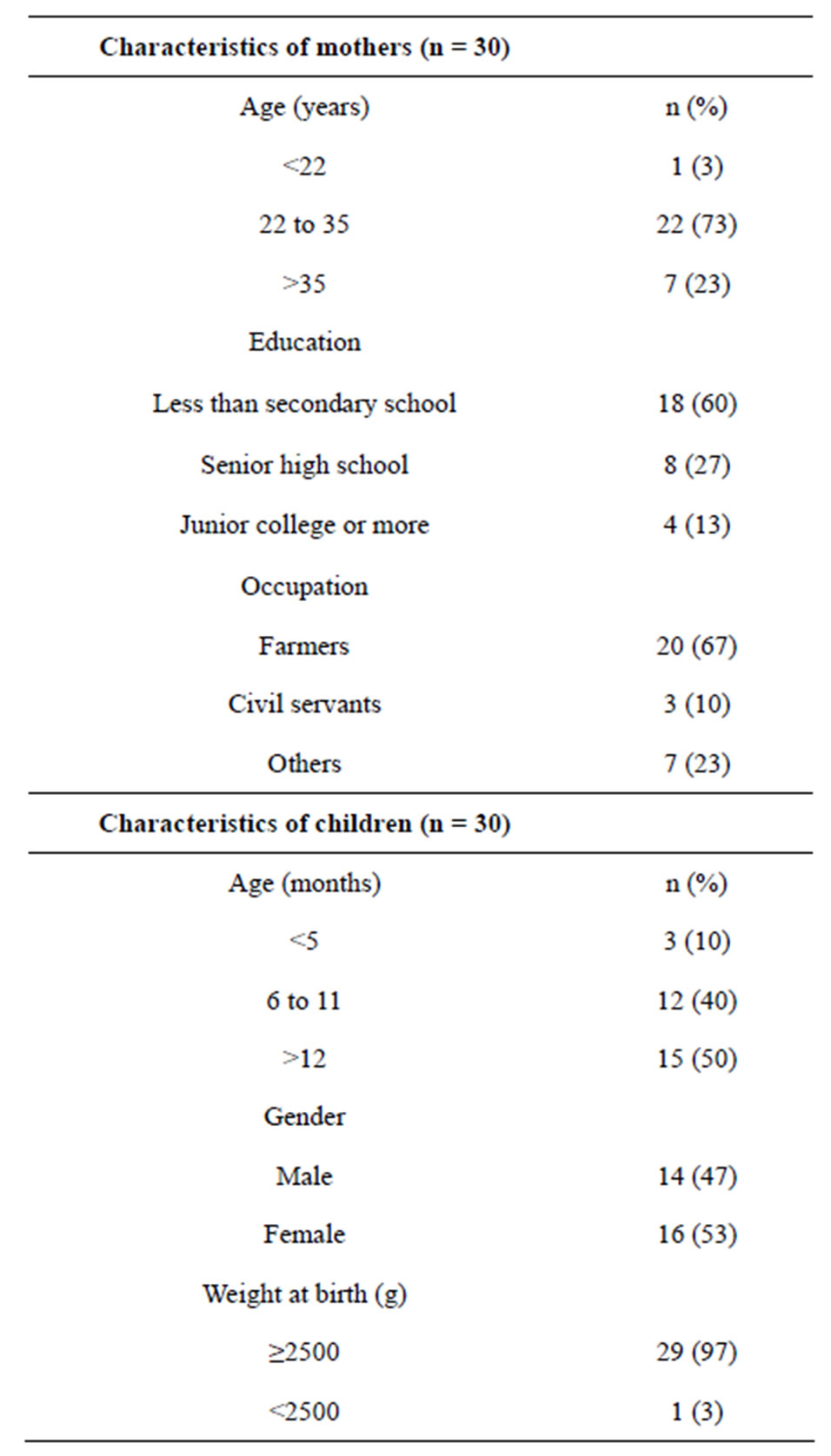

In this study, all the invited mothers, i.e. 30 mothers, agreed to participate. The demographic characteristics of the participants and their children are shown in Table 1. The mean age of the mothers in the group was 30 years

Table 1. Characteristics of the mothers and their children.

of age, but their ages ranged between 22 and 35 years. The average age of the children was 13 months.

Knowledge of Nutrition When Breastfeeding

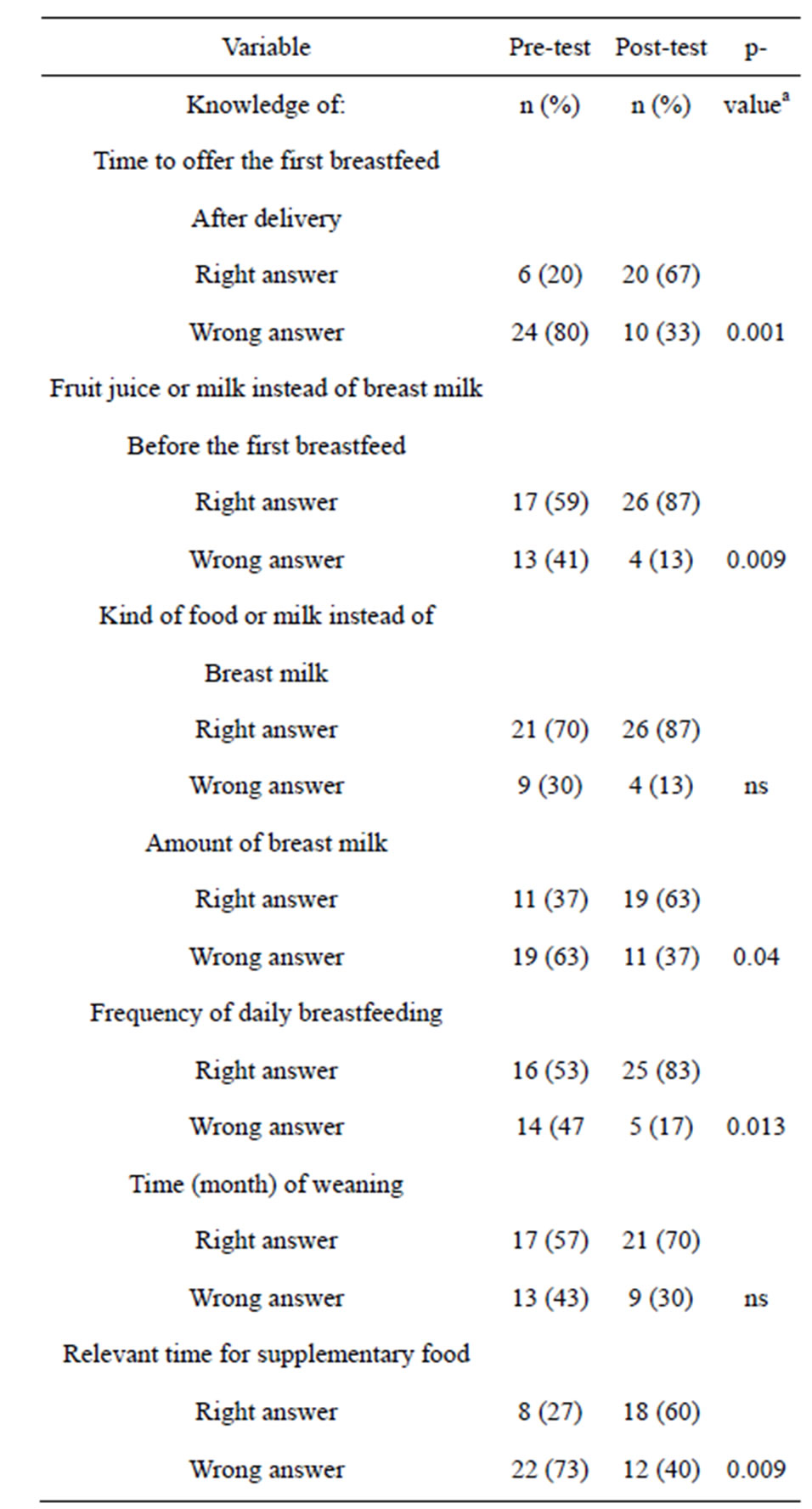

Table 2 summarises the findings related to the mothers’ knowledge of nutrition during the time of breastfeeding. The time at which the first breast feed was offered was collected by asking the responders to choose the most correct answer; less than 30 minutes after birth or 30 minutes to 2 hours after birth or up to 2 hours after birth or do not remember. In the pre-test, only six mothers answered according to guidelines from the course, i.e. less than 30 minutes after birth. After the course, statistically significantly more mothers (67%) answered according to the guidelines (p = 0.001).

In addition, the mothers were asked to state whether they offered fruit juice or milk instead of breast milk

Table 2. Mothers’ knowledge of nutrition during breastfeeding before and after the one-day nutrition course (n = 30).

achi2 test, p < 0.05; ns = non-significant.

before the first breast feed. The majority of the mothers in both the pre-test and post-test said that they did not give any other food or drink before, 59% and 87% respectively. The others still thought that fruit juice was the best. The differences between pre-test and post-test were found to be statistically significant (Table 2).

The mothers were asked how to produce more breast milk by choosing better nutrition and diet or breastfeeding more frequently or doing nothing. In the post-test, 63% answered according to the guidelines, i.e. better nutrition and diet or breastfeeding more frequently (p = 0.04).

The majority of the mothers in the pre-test understood the importance of increasing the breastfeeding frequency when they did not have enough milk and the number of mothers with this knowledge increased after the course (p = 0.013).

Regarding time of weaning, the mothers were asked about their intention to breastfeed. The majority of the mothers intended to breastfeed for at least 12 months or longer. There was no statistically significant difference between pre-test and post-test.

The time at which to offer supplementary food to children was also a concern in the intervention. The mothers were asked “When is the most suitable time to give supplementary food to children?” with several suggestions. After the course, the number of mothers who answered according to guidelines, i.e. after six months, increased from 27% to 60% (p = 0.009).

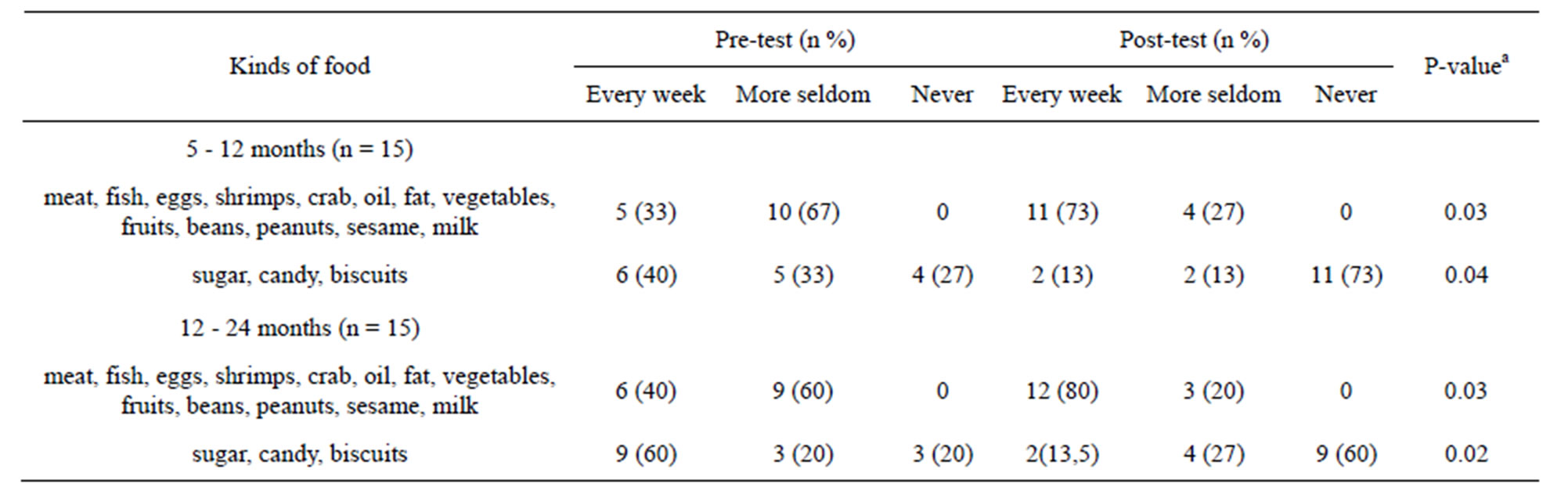

The types of food which are suitable for children were introduced in the nutrition course. After the course, the researcher asked the mothers to list the names of food that was cooked for their children. In the pre-test, none of the suitable foods was chosen for meals for children every week at the ages of 5 - 12 months and 12 - 24 months (33% vs. 40%). However, the post-test result showed that this food was chosen on a weekly basis in meals for children aged 5 - 12 months and 12 - 24 months (73% vs. 80%). There was a statistically significant difference between the pre-test and the post-test (p = 0.03) (Table 3).

Moreover, there was a decrease in the use of sugar, candy and biscuits in meals for children aged 5 - 12 months and 12 - 24 months in the post-test (p = 0.04 and p = 0.02 respectively). In terms of knowledge, the mothers reported using sugar, candy and biscuits less frequently.

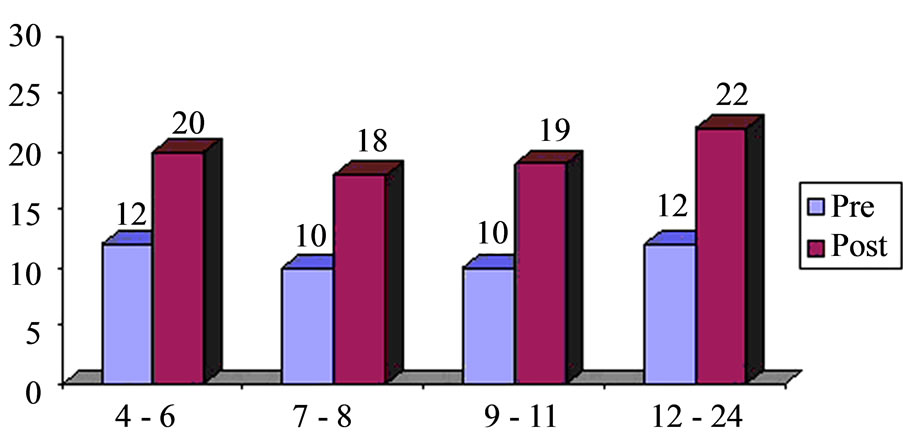

According to the nutrition guidelines, there are recommendations about additional meals per day related to the age of the children. When it came to meals per day, in which breastfeeding was not included, the mothers were asked how many meals they offered their children at certain ages, 4 - 6 months, 7 - 8 months, 9 - 11 months and 12 - 24 months. Figure 1 summarises the number of additional meals per day in the different age groups in the preand post-test. The results showed that there was a statistically significant increase in the number of meals for all age groups when comparing before and after the course. The percentage of respondents answering according to the guidelines among the mothers in the pretest and post-test was 40% and 60% for children aged 4 - 6 months, 33% and 60% for children aged 7 - 8 months old, 33% and 63% for children aged 9 - 11 months and 40% and 73% for children aged 12 - 24 months (Figure 1).

One of the purposes of the nutrition course was to provide information about how to care for a child when

Table 3. Consumption and frequency of different types of food before and after the course.

achi2 test, p < 0.05.

Figure 1. Numbers of additional meals per day in the different age groups.

he/she is sick or suffering from diarrhea. A question was asked about whether children should be put on a special diet when they become sick/develop diarrhea. In the pretest, only 47% of the mothers in the group answered according to the guidelines, i.e. still breastfeeding from the breast or a spoon. The percentage of mothers who answered this question in the post-test increased from 47% to 73% (p = 0.04) (data not shown).

4. DISCUSSION

The main result of this pilot study showed that a oneday nutrition course increased mothers’ knowledge about a number of important nutritional issues according to the guidelines. There was an increase in the knowledge relating to breastfeeding less than 30 minutes after delivery, not giving milk or fruit juice instead of breast milk, increasing the frequency of breastfeeding in the event of producing less milk and knowledge about giving supplementary food after six months. Moreover, the results revealed that the mothers reported an improvement in their knowledge of the consumption and frequency of more healthy food supplements, such as meat, fish, eggs and so on and less sugar, candy and biscuits, on a weekly and daily basis.

According to the nationwide campaign, the Malnutrition Prevention Programme in Vietnam, it is suggested that mothers should breastfeed their children within the first 30 minutes after delivery because, when the child is breastfed, prolactin and oxytocin are produced by the pituitary gland. Prolactin stimulates the milk gland to secrete milk, while oxytocin stimulates milk to secrete [20]. The nutritional course therefore demonstrated its effectiveness, as there was a significant change in this pattern of knowledge among the mothers. Even if the study population in the current study was small, the result is in line with Sasaki et al. (2010), who reported that only 39% breastfed their children 30 within minutes after delivery. This indicates that knowledge of this pattern is fairly low and that increased knowledge is necessary.

In the present study, however, around 25% did not learn about healthy nutrition. This percentage corresponded to the level of malnutrition in young children in this rural area in Vietnam [9,10]. There may be some explanations of why the intervention not did reach 100%. Vietnamese mothers, especially mothers living in rural or mountainous areas, usually give their children fruit juice or honey after birth. Before the nutrition course, many mothers chose to give their children fruit juice or honey before the first breast feed. According to WHO recommendations, it is not necessary to give the child any kind of food instead of breast milk before the first breast feed. Breast milk can supply nutritional needs for the child during a period of 4 - 6 months, without any extra food in the first few months [4].

Before the nutrition course, 59% of the mothers used other kinds of milk to replace the lack of mother’s breast milk and this pattern of knowledge increased in terms of the chosen item to 87% after the course. In fact, many of the mothers know that other kinds of milk are good for their children if they do not have enough breast milk, but their financial capacity is limited so they are unable to provide their children with these other kinds of milk. Some mothers therefore use rice water to replace breast milk. The economic factor actually leads to additional meals being given at an earlier stage than suggested, because these mothers think rice water is not enough in terms of energy for their children. This course provides knowledge not only of nutrition for children but also of how to use or make milk from local products such as soya milk to provide more nutrients for children within their financial capacity.

According to the labour legislation in Vietnam, mothers are allowed to be free from work for four months after the delivery [21]. This time covers the period both before and after the delivery. When mothers return to work, they are allowed to arrive at their workplace one hour later or leave one hour earlier to breastfeed until their children are one year old. The mothers in the study are farmers whose working hours are flexible. This gives them an advantage in terms of breastfeeding time for their children, compared with mothers living in a large community without flexible working hours. The positive effect of flexible work in combination with exclusive breastfeeding has also been confirmed previously [22].

Regarding time of weaning, there was no significant difference between pre-test and post-test. However, more than half the mothers intended to breastfeed their children for at least 12 months or longer. Only a few children were weaned before 12 months of age because the mothers did not have enough breast milk. The knowledge of time for weaning might be explained by their occupation as farmers, which gave them more chance to breastfeed their children than mothers with other occupations. However, the children of farming mothers have been associated with stunting in another study in Vietnam [10]. In spite of this, almost all the children in the current study were not underweight. Another aspect, which has not been studied here, is the increased risk of dental caries when breastfeeding for too long and an early start with sweetened drinks and food. Co-operation between professionals in dental care and general health professsionals would be preferable when working on nutrition for children.

In answer to the question about the pattern of time for offering supplementary food to children, more mothers reported that they gave their children supplementary food at sixth months of age than before that age (27% before and 60% after). Even if this changed in a positive direction after the course, the children were still given additional meals earlier than suggested due to poor financial capacity and the mothers’ early return to work after delivery. This could be explained by the mothers concern about the risk of malnutrition and uncertainty about nutritious food. Moreover, the consumption and frequency of supplementary food was not in line with the guidelines for healthy food, but this improved after the course. A recent study confirms that information on complementary feeding is limited in Vietnam and needs to be strengthened [14].

Studies aiming to evaluate programmes for preventing malnutrition and promoting the growth of children in Vietnam have been conducted and they highlight the importance of implementing exclusive breastfeeding and nutritional food habits early in life [5,7,10,12,23]. This nutrition course is fairly effective as it increases the mothers’ knowledge of nutrition in children. The mothers were educated to choose better food for their children based on their financial capacity and the availability of food. Many vegetables are rich in protein and provide a great deal of energy and they are much less expensive in comparison to animal food. For example, 100 g of beans provide 300 - 400 calories. However, many mothers did not pay any attention to this before the course. For example, beans, nuts and sesame seeds are rich in protein and these kinds of food are rich in vitamins and minerals.

The majority of the mothers did not give their children eggs, fish, meat, oil, fat, shrimps and crab when they suffered from diarrhea. They thought that this food would make their children more seriously ill. These figures improved after the course. However, diarrhea in the last two weeks has not been associated with underweight, stunting or wasting [10].

To acquire knowledge which may affect healthy behaviour which is advantageous in terms of exclusive breastfeeding and nutritious food intake in young children, different factors have an impact. The study population in the current study was living in a rural area, had an average age of 30, a low educational level and the majority were farmers. Moreover, the average age of the children was 13 months and their weight at birth reveals that these children were not underweight. The above-mentioned features in mothers and children, as well as other important factors which have not been included in this study, could directly or indirectly affect the child care provided by the mothers, as well as their ability to acquire knowledge. Other Vietnamese studies reveal that the determinants of malnutrition are complex and are related to socio-economic, environmental, maternal and individual factors [9,10,14]. All these factors, but also factors related to behavioural change, such as self-efficacy [24], must be considered when implementing nutrition promotion programmes.

Vietnam is moving towards an improved economy and various health initiatives have been implemented. However, this study confirms that the knowledge of nutrition and exclusive breastfeeding is limited in rural areas, which have not yet been reached by health-promotion programmes. Even if this study had a small population, it shows that education for mothers with children less than two years of age could be a step towards improving their knowledge of nutrition and during breastfeeding.

Except the limitation of a small population, some critique about the method could be made. This study assessed the mother’s knowledge two weeks after a oneday course. This could be seen as to short, as time make us to forget some of the knowledge, especially if it doesn’t follows up by some kind of strategy to maintain the new knowledge. Moreover, knowledge does not always leads to a behaviour change. To influence and assess mother’s nutrional knowledge about breast feeding, a larger population from different areas using an intervention based on change and parity approaches would be recommended to draw more general conclusions.

5. CONCLUSION

There was a lack of knowledge about breastfeeding and nutrition among mothers with children under two years of age. The one-day nutrition course increased their knowledge of every aspect of nutrition. This is important in order to prevent malnutrition and its consequences in the target group. These results indicate the importance of continuing with nutritional education and contributing to an additional piece of the puzzle when it comes to finding key audiences in an effort to improve the knowledge of nutritious foods for children early in life.

6. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge the study participants for their time and effort.

REFERENCES

- Muller, O. and Krawinkel, M. (2005) Malnutrition and health in developing countries. Canadian Medical Assosiation Journal, 173, 279-286. http://dx.doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.050342

- Struble, M.B. and Aomari, L.L. (2003) Position of the American Dietetic Association: Addressing world hunger, malnutrition, and food insecurity. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 103, 1046-1057. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0002-8223(03)00973-8

- American Academy of Pediatrics. (2012) Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics, 129, e827-e841. http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-3552

- WHO (2002) The optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding: A systematic review. World Health Organization, Geneva.

- Marsh, D.R., Pachon, H., Schroeder, D.G., Ha, T.T., Dearden, K., Lang, T.T., Hien, N.D., Tuan, D.A., Thach, T.D. and Claussenius, D.R. (2002) Design of a prospective, randomized evaluation of an integrated nutrition program in rural Viet Nam. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 23, 36- 47.

- Schroeder, D.G., Pachon, H., Dearden, K.A., Kwon, C.B., Ha, T.T., Lang, T.T. and Marsh, D.R. (2002) An integrated child nutrition intervention improved growth of younger, more malnourished children in northern Viet Nam. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 23, 53-61.

- Pachon, H., Schroeder, D.G., Marsh, D.R., Dearden, K.A., Ha, T.T. and Lang, T.T. (2002) Effect of an integrated child nutrition intervention on the complementary food intake of young children in rural north Viet Nam. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 23, 62-69.

- UNICEF (2003) Nutrition state in Vietnam from 2000- 2002. (Nutrition Io ed. pp. 5, 7-8, 23.) Medical Publisher, Hanoi, 5,7-8,23.

- Nakamori, M., Nguyen, X.N., Nguyen, C.K., Cao, T.H., Nguyen, A.T., Le, B.M., Vu, T.T., Bui, T.N., Nakano, T., Yoshiike, N., et al. (2010) Nutritional status, feeding practice and incidence of infectious diseases among children aged 6 to 18 months in northern mountainous Vietnam. The Journal of Medical Investigation, 57, 45-53. http://dx.doi.org/10.2152/jmi.57.45

- Nguyen, N.H. (2009) Nutritional status and determinants of malnutrition in children under three years of age in Nghean, Vietnam. Pakistan Journal of Nutrition, 8, 958- 965. http://dx.doi.org/10.3923/pjn.2009.958.964

- Muller, O., Garenne, M., Kouyate, B. and Becher, H. (2003) The association between protein-energy malnutrition, malaria morbidity and all-cause mortality in West African children. Tropical Medicine & International Health, 8, 507-511. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-3156.2003.01043.x

- Sasaki, Y., Ali, M., Kakimoto, K., Saroeun, O., Kanal, K. and Kuroiwa, C. (2010) Predictors of exclusive breastfeeding in early infancy: A survey report from Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 25, 463- 469. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2009.04.010

- Dolgun, G. and Yuksel, A. (2010) Assessing mandated breastfeeding education in Istanbul. MCN, American Journal of Maternal Child Nursing, 35, 293-296. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/NMC.0b013e3181e62802

- Nguyen, P.H., Menon, P., Ruel, M. and Hajeebhoy, N. (2011) A situational review of infant and young child feeding practices and interventions in Viet Nam. Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 20, 359-374.

- Ha, P.B., Bentley, M.E., Pachon, H., Sripaipan, T., Caulfield, L.E., Marsh, D.R. and Schroeder, D.G. (2002) Caregiver styles of feeding and child acceptance of food in rural Viet Nam. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 23, 95-100.

- Freedman, M.R. and Alvarez, K.P. (2010) Early child- hood feeding: Assessing knowledge, attitude, and practices of multi-ethnic child-care providers. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 110, 447-451. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jada.2009.11.018

- Department of Nutrition and Hygiene, Safety Food. (2004) Nutrition and hygiene, safety food. 2nd Edition, Department of Nutrition and Hygiene sf ed. Hanoi Medical University, Medical Publisher, Hanoi.

- Ministry of Public Health. (2006) The campaign of malnutrition prevention program in national. Hanoi.

- WMA (1964) World medical association declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Vol. 2008, WMA, Helsinki.

- Nguyen, C. (2002) The mission of malnutrition prevention in 2008-2010 stage. Journal of Nutrition & Food Sciences, 14, 58-62.

- Custumes (2008) DN: Labour law. 114 clause. Departments PC ed. Dong Nai. http://www.dncustoms.gov.vn/Data/Luat/luat_lao_dong.htm

- Dearden, K.A., Quan le, N., Do, M., Marsh, D.R., Pachon, H., Schroeder, D.G. and Lang, T.T. (2002) Work outside the home is the primary barrier to exclusive breastfeeding in rural Viet Nam: Insights from mothers who exclusively breastfed and worked. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 23, 101-108.

- Tanaka, K. and Miyake, Y. (2012) Association between breast-feeding and dental caries in Japanese children. Journal of epidemiology/Japan Epidemiological Association, 22, 72-77.

- Dearden, K.A., Quan le, N., Do, M., Marsh, D.R., Schroeder, D.G., Pachon, H. and Lang, T.T. (2002) What influences health behavior? Learning from caregivers of young children in Viet Nam. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 23, 119-129.

NOTES

*Competing interests: The authors report no financial or competing interests.

Authors’ contributions: HN was responsible for the data collection and writing. HN conducted and AB assisted with data analysis. AB and UL were responsible for writing, revising the manuscript and the decision to publish. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.