Health

Vol.5 No.10(2013), Article ID:37751,6 pages DOI:10.4236/health.2013.510222

Pregnant women’s awareness and acceptance of epidural anesthesia and its influence on cesarean section rate control in China: A qualitative study*

![]()

1Department of Health Promotion, Bao’an Maternity and Child Health Hospital, Shenzhen, China;

2Health Care Department for Women, Bao’an Maternity and Child Health Hospital, Shenzhen, China #Corresponding Author: ljm3712@126.com

Copyright © 2013 Ruirui Chen et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received 5 June 2013; revised 5 July 2013; accepted 15 August 2013

Keywords: epidural anesthesia; awareness; qualitative; cesarean section

ABSTRACT

Background: Epidural anesthesia, as an effective pain relief method, could be viewed as an attempt to encourage vaginal delivery and control cesarean section. Increased demand caused by psychosocial factors such as fear of childbirth and labor pain is supposed to be one predictable drive of high cesarean section rate in present China. Little qualitative information on women’s awareness and perceptions of epidural anesthesia was found, but conscious efforts should be focused on this part to help generate policy-making priority. Methods: This study was carried out under an exploratory descriptive design in Bao’an Maternity and Child Health Hospital. Those interested in participating would be invited to focus group discussion or individual interview according to a semi-structured openended guide after collecting the participants’ demographic characteristics. The thematic content analysis approach was used for data analysis. Results: Five major themes were identified: 1. the sources to gain information on epidural anesthesia; 2. clinical impact; 3. social impact on awareness; 4. association between epidural anesthesia and cesarean section; 5. attitudes and questions about the current service implementation. Discussions: The interplay between pregnancy knowledge, socio-economic conditions, social support, insurance policy environment, women’s judgment of health care quality influences the ways women acknowledge and utilize epidural anesthesia service. Conclusions: As maternal requested CS due to low pain tolerance emerges gradually, natural labor with epidural anesthesia is a more suitable childbirth option, which is also expected to function in reducing CS rate by service-providers and administrators in the health departments of China besides building up a pain-free labor environment.

1. BACKGROUND

Epidural anesthesia (EA), as the commonest form of labor analgesia, is widely considered as an effective pain relief method in western countries and used to save anesthetic time when a cesarean section (CS) is needed [1,2]. It is worth to note that as a way to make childbirth less difficult and more acceptable for mothers, this intervention is intensively discussed recently from an autonomous perspective that pregnant women have rights to make a choice to reduce the pain as much as possible, although interfering with natural delivery is still yet to be justifiable on a religious, moral or ideological level [3]. So far, there has been a hot debate on the benefits and risks of this obstetric intervention because of uncertain outcomes including longer second stage, intra-partum fever and increased risk of operative vaginal and cesarean delivery based on inconsistent literature results [4-6]. Systematic review studies, however, demonstrated that EA has no impact on the risk of cesarean section, instrumental vaginal delivery for dystocia, long-term backache, breastfeeding or neonatal Apgar scores [7,8].

The co-operation program of “No pain N” Labor’ has triggered the Chinese large-scale EA use through introducing the American experience and strengthening bilateral communication among professionals in the US and China. According to previous studies on EA implementation, the intervention could also be viewed as an attempt to encourage vaginal delivery and control cesarean section [9-12]. In present China where CS rate is estimated to be 46.2% in a cross-sectional WHO study, far higher than the alert level of 15%, increased demand caused by psychosocial factors such as fear of childbirth and labor pain could be one predictable drive [13,14]. Therefore, local tailored strategic plans need to be addressed to reduce this kind of maternal requested CS.

Although lots of Chinese studies have similar results to verify EA’s effect comparing maternal and neonatal indicators with those having natural vaginal birth and this service started more than 10 years ago, there is little qualitative information on women’s awareness and perceptions of this intervention. It is recommended that conscious efforts should be focused on women’s concerns and opinions on health care to help generate policy-making priority. Furthermore, data on local contexts play important roles in translating conceptual theories into culturally appropriate and effective maternal care intervention.

The following study aims to identify local pregnant women’s awareness and acceptance of EA to adjust the tailored hospital-based program and exert positive influence on reducing maternal requested CS.

2. METHOD

2.1. Study Setting

This study was carried out from Sep. 1st under an exploratory descriptive design in Bao’an, a less-developed district with 6 million population in Shenzhen, an immigrant city of China. The childbirth amount was around 65,000 in recent years and it increases steadily every year. The maternity and child health hospital admits high-risk pregnancies and provides technical and clinical assistance throughout the district. Its childbirth amount makes up about 12% of the district overall birth population. As for the EA service, 24-hour on-duty rule and specialized obstetric anesthetists have been set to guarantee the access to this service since 2009 and the reasonable price of EA makes it affordable to decrease the socioeconomic inequalities as much as possible.

2.2. Subjects

In the routine work, health information related to prenatal preparation, nutrition, laboring process, mental health maintaining, breast-feeding and common neonatal diseases are given to voluntary pregnant women in a form of fixed and scheduled health education class three times a week. Each class has one focus on the maternal or neonatal health promotion aspects. The introduction class of EA given by anesthetists has been added to the schedule since this March.

During each class, the researcher informed the attendants about the aim and the procedure of the study. Those interested in participating would be invited to focus group discussion (FGD) or individual interview, according to the number of the voluntary participants, after receiving verbal consent [15,16]. No one was explicitly excluded by the researcher once they decided to participate. The study lasted for one and a half months from Sep. 1st to Oct. 14th. The Research Ethics Committee of the hospital reviewed and approved this research project.

2.3. Data Collection

The purposive sampling method was used to gain the representation of the target population and the sample size was determined using saturation sampling [17]. The participants’ demographic characteristics (age, education attainment) and maternal features including gestational age, mode of latest childbirth and adverse pregnancy history were collected using a structured questionnaire [18]. The semi-structured open-ended interview guide comprised topics and probing questions:

1) Where do you get information on EA?

2) Do you have social or emotional support from your husband or other relatives and friends regarding EA?

3) Do you ever think about the service cost and relative health insurance reimbursement?

4) Does EA have any influence on your birth mode?

5) What information of EA do you want to gain from the professionals?

Individual interview lasted around 20 - 30 minutes while FGD lasted about 1 hour with the group number ranging from 3 to 7 people. The interviews and discussions were tape-recorded, and if this was not possible, detailed notes were taken.

2.4. Data Analysis

Data were collected in Chinese. The researcher sorted and coded the content of the narrative description to reduce data into concepts the same day of the interview [19].The researcher reviewed again the process of data collection and the quality of the transcriptions at the end of each week of the study duration. The categories of related data and development of clusters reflecting similar issues and experiences were generated using the thematic content analysis [20,21]. Another experienced researcher’s opinions was obtained on the extent of these categories fitting and describing the data and theme development. The themes built up in an iterative process were cross-checked and the interpretation was modified accordingly before refining the analysis to improve the validity of emerging themes [15,22,23].

3. FINDINGS

The 18 participants’ age ranges from 25 to 35 years old with the median age of 29. Two of them are in their second trimester while the other sixteen in the third trimester. Junior college and higher level is attained by 14 participants while 4 have high school educational background. There are 16 primiparas, and 2 multiparas who both had vaginal birth in their latest delivery. Among four participants with adverse pregnancy history, two had miscarriage and 1 had ectopic pregnancy.

Five major themes were identified based on the interview guide in the study, followed by illustrative quotations from the participants.

3.1. The Sources to Gain Information on EA

The women interviewed here reported they were more likely to gain peer information from those who had EA in previous childbirth via verbal communication or reviewing baby-raising blogs, which is considered as a secure and cost-saving method. According to the narratives of those who experienced EA, their babies seldom had any problem and were thought to be very healthy.

“My friend had it (referring epidural anesthesia) three years ago and it had no side-effects.”

“I chat with my friends in the US and Hong Kong. They informed me no regrets of using it!”

However, any symptom that was not expected in a normal labor is considered to attribute to the only addition of EA use compared to no-intervened natural childbirth without consulting practitioners. This “take it for granted” attitude raised possibilities to disseminate wrong information in an informal channel to a large extent.

“One of my friends who had EA has apparent memory loss and intelligence reduction. She thinks it affects her brain.”

“Babies born after EA use have a longer head length than those without.”

3.2. Clinical Impact

3.2.1. Possible Impact on Maternal and Neonatal Health

The majority of women in the present sample had little awareness about the injection time and site and the procedure of EA, while was concerned about the sequelae no matter they have initial impression of this service or not. So their immediate reaction was to ask whether it brings sequelae or not.

“The perfect childbirth is the one with less pain and least impact on maternal health and fetus’ well-being. How long can it keep me in pain-reducing status and how much it reduces? I need to know the whole process and kinds of possible impact.”

“It is heard that EA could lengthen the laboring process, but I know it could not be caused by EA. Am I allowed to walk after it?”

Most interviewees had strong interests in more professional explanations regarding the harmful impact on the exact parts of their body and neonatal health rather than general description. Their eagerness indicates they are more likely to assess advantage and disadvantage with discretion.

“Does it influence the lower extremity nerve conduction or urination function?”

“Does it have influence on memory? Mine is not so good.”

“Will anesthetic drugs enter my baby through blood circulation and placenta?”

Besides confusions caused by knowledge limitations, there have been pregnant women holding objective views after consideration of various situations during the dynamic labor process.

“EA is acceptable because the anesthetic service has to be used when there is dystocia and cesarean section.”

3.2.2. Questions about the Symptoms That Could Happen

Backache is the commonest symptom that pregnant women can perceive easily, which is also an important factor to self-assess post-operation health condition despite that no apparent influence on normal life was found in the study sample.

“I have a friend from the US who used EA in her previous two childbirths. She had backache and she suggested me not have it. My sister-in-law also had backache with EA.”

“The back-pain lasted for one year after labor. I had no idea that I was the first one to have EA in a local private hospital in 2006. Although the experts were hired from Shanghai, the anesthetic injection succeeded after three times’ attempt.”

3.3. Social Impact on Awareness

3.3.1. Price and the Fertility Insurance Reimbursement

A large proportion of participants and their partners reported they would inquire about the price immediately followed by the sequelae query while few claimed they would not care about the cost of the service.

“I would ask whether it can be reimbursed by fertility insurance first.”

“I haven’t thought about the cost problem. It is not a problem for me.”

3.3.2. Social and Emotional Support

Many participants just mentioned this service to their family members but without in-depth discussions or communications, while several wanted to gain consent from their husbands after a brief understanding.

“My husband and I haven’t discussed about it because we both know little about it.”

“My husband doesn’t allow me to have it because he thinks it is harmful to our baby. I need a doctor to explain to him.”

3.4. Associations between EA and CS

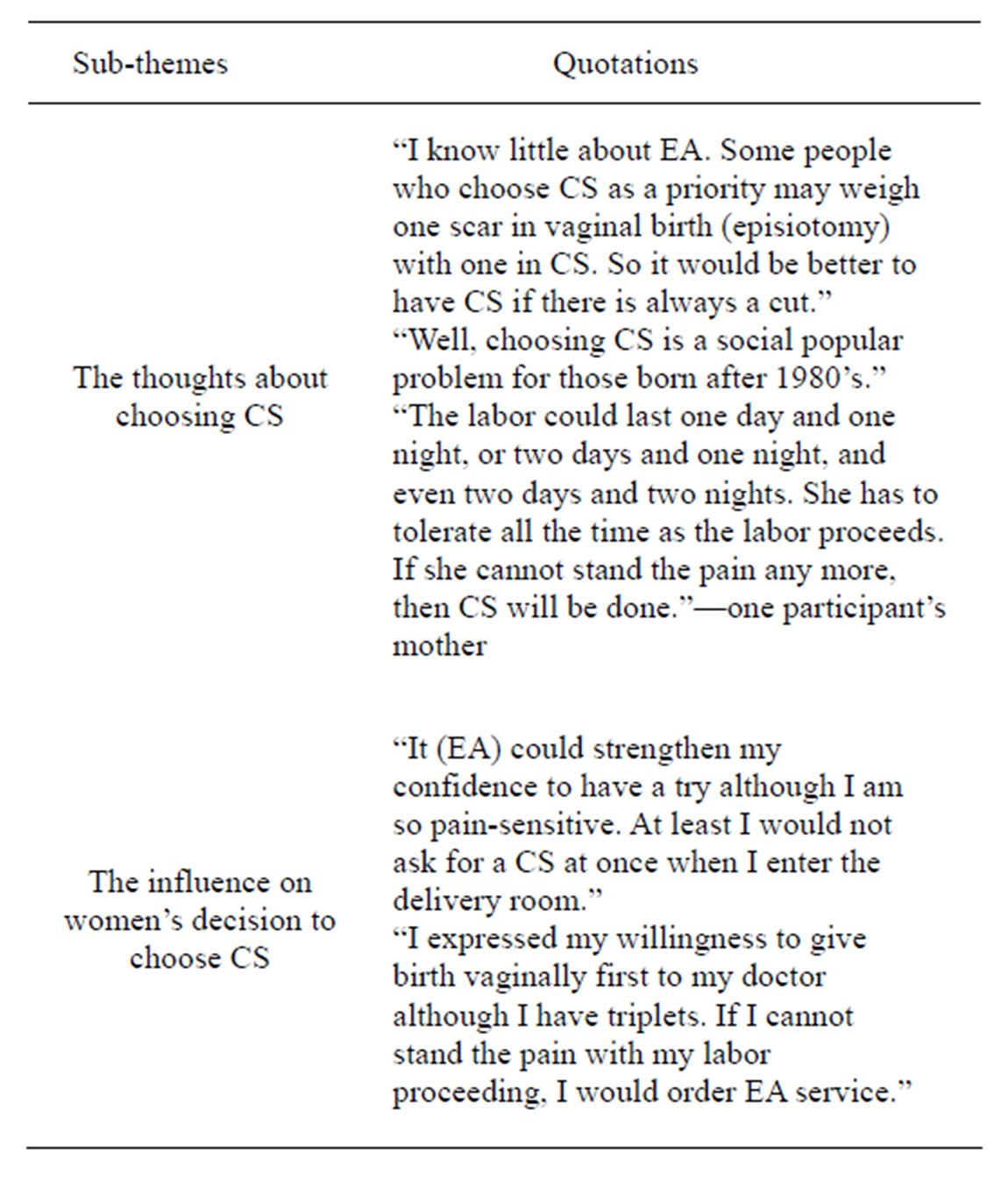

There are representative ideas about choosing CS from the sampled interviewees and when it comes to the association between having EA and CS, negative effect was found. This theme was divided into two sub-themes: one is present thoughts on having maternal requested CS, the other is how natural childbirth with EA can replace CS under some circumstances from an individual point of view (see Table 1).

3.5. Attitudes and Questions about the Current Service Implementation

Both good and bad voices are gained that pregnant women’s judgments on EA are built not only from medical attainment, but also from psychosocial perspectives.

“It can be introduced if the technique is mature because the society and medicine is in progress. Why should I bear the pain if it can be reduced?”

“If it is good, why it is not included in the fertility in-

Table 1. Association between EA and CS.

surance reimbursement package?”

The following quotes reflect these three participants’ anxiety and concerns of current situation. It suggests that some still have uncertain attitude on the possibility to have a safe and satisfactory pain-reducing labor, although systematic research and comparison of the service supply have been done. Clinical skills and practice criterion are among the main considerations.

“Whether the success is highly related to the anesthetists’ skills and personal capacity?”

“My husband is a surgeon and I know something about EA. I am not skeptical of the technique and the medicine safety for it has been used in western countries widely. However, there are risks in the subjective cooperation between obstetricians and anesthetists. Considering the anesthetic technique is so professional and highclass, I do not want to be one of the problematic 1% in the pilot period of this program. Meanwhile, I would prefer the experts with many years’ clinical experiences in the capital city of Beijing than younger doctors here. I have not made my decision yet.”

“Why the practice here is different from the American or Hong Kong style regarding the same labor process? We’d better conform to the international standard. Anesthetists in the US or Hong Kong won’t wait until the cervical dilation is 3 cm, but do EA directly at the time of ruptured membranes. If the labor progresses quickly, can EA service and anesthetists here be in place to make anesthetic drugs work during the short time of cervical dilation from 3 cm to full openness? It is all about the service!”

4. DISCUSSION

This study explored the opinions and concerns of pregnant women on EA in a relatively deprived area in the immigrant city of Shenzhen, China. Several issues were identified to reflect the current situation after EA service has been implemented in this maternity and child health hospital since 2009.

Findings here indicate that the most frequently mentioned source of related information on EA is from service-experienced peers. Similar result can also been found in another Japanese study [24]. This indicates those interested in reducing labor pain are more likely to gain the first-hand information from the accessible users’ depictions not the practitioners’ professional advice, which raises the question that the service-users may have misconception of EA and convey the wrong views to women lacking professional medical knowledge for making judgments. In this study, the participants’ acknowledgement level is relatively low, which can also be seen in To’s study on awareness of Hong Kong population, and they are more concerned about the harmful effect on neonatal health [25].

Studies suggest that social support was related to positive health behaviors [26]. However, the partners’ support tends to make several participants take conservative measures in our sample. It should be realized that the partners usually acquire relative information in an indirect way, indicating pregnant women are the main subjects of health education and invoking partners’ more involvement both in decision-making and information seeking process.

The health education program meets the requirements of women who want to find out more about EA and weight the pros and cons according to their own circumstances. Through observation and communication with the attendants, a simple flow diagram of EA service procedure could be used to help them figure out how the obstetricians and anesthetists coordinate and what they should act accordingly from the time they enter the hospital. The EA related information flows from professionals to pregnant women attending the program, then to their partners and peers of similar age. So the concept of maternal requested CS caused by labor pain fear can be corrected step by step.

A considerable proportion of the participants reported how the price and the fertility insurance reimbursement regulations function during their decision-making process while some have special requirements on high-quality service with high cost. As for health service utilization, the fertility insurance is an effective method to make effective supplementation. Thereafter, unified reimbursement regulation would reduce the socioeconomic disparities on the service utilization as supposed and eliminate adverse influence on people’s judgment of EA as well.

Clinical skills and practice criterion, seen as guarantees of safe and satisfactory health service provision, generate the two major concerns of the women who had attended the EA introduction program. Qualitative evidence of our study makes the development direction of EA service clear that high-level skills of obstetric and anesthetic practitioners and more exchange with advanced hospitals in relative fields could meet the potential demands of pregnant women in future.

5. LIMITATION

In the process to carry out the study there are two main limitations. One is the participants involved are those who attend antenatal pregnancy care and health education class and improve their pregnancy quality under professional assistance in a maternity and child health hospital. They are more likely to be highly educated primiparas and willing to learn new things and share their ideas and experiences. Therefore, the findings cannot be generalized to the whole local pregnant women population, but served as an initiative reference. A national study found that higher educational attainment is an important determinant of CS rate in developed urban city including Shenzhen, where our study was conducted [27]. Those women interviewed in our study could be the representatives of the target population to reduce CS rate. The other potential bias is the role the researcher had. As to minimize the interviewer’ effect, the first author did all the interviews according to the pre-defined procedure, and she would answer the participants’ relative questions and communicate with them during the interviews.

6. CONCLUSION

In general, the interplay between pregnancy knowledge, socio-economic conditions, social support, insurance policy environment, and women’s judgment of health care quality influences the ways women acknowledge and utilize EA service. Women’s right of making decisions to reduce pain should be respected and understood. Also, carrying out health education program is the first step to enhance the awareness of EA proactively.

To control and reduce CS rate is a big obstetric challenge in present China. As maternal requested CS due to low pain tolerance emerges gradually, EA implementation is not only a labor analgesia service, but a more suitable option during childbirth. The participants’ response in this study verifies the feasibility of this tentative plan. However, the professionals such as anesthetists and obstetricians are supposed to better inform the users about the possible symptoms and questions like backache and solutions to avoid misunderstandings and exaggerations of its risks, meanwhile the follow-up of the service-users is vital.

For service-providers and administrators in the health department, EA implementation is expected to function in reducing CS rate in China besides building up a painfree labor environment. Further quantitative study on evaluation of EA implementation and comparison of postpartum health status between vaginal birth with EA and maternal requested CS without medical indications in the hospital can help provide evidence to those who are still skeptical of current situation.

7. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank all participants in the research for their time and Ms. Xinyi Wang for her suggestions on the English translations.

REFERENCES

- Lurie, S. and Priscu, V. (1993) Update on epidural analgesia during labor and delivery. The European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, 49, 147-153. doi:10.1016/0028-2243(93)90263-C

- Morishima, H.O. (2007) Labor analgesia in the US and Japan. Masui, 56, 1040-1043.

- Schneider, M.C. (2002) Analgesia during labour: From taboo to evidence-based medicine. Anaesthesist, 51, 959- 972. doi:10.1007/s00101-002-0414-6

- Eriksen, L.M., Nohr, E.A. and Kjaergaard, H. (2011) Mode of Delivery after Epidural Analgesia in a Cohort of LowRisk Nulliparas Birth, 38, 4. doi:10.1111/j.1523-536X.2011.00486.x

- Lieberman, E. (1999) No free lunch on labor day. The risks and benefits of epidural analgesia during labor. Journal of Nurse Midwifery, 44, 394-398. doi:10.1016/S0091-2182(99)00057-9

- Thorp, J.A. and Breedlove, G. (1996) Epidural analgesia in labor: An evaluation of risks and benefits. Birth, 23, 63-83. doi:10.1111/j.1523-536X.1996.tb00833.x

- Marucci, M., Cinnella, G., Perchiazzi, G., Brienza, N. and Fiore, T. (2007) Patient-requested neuraxial analgesia for labor. Anesthesiology, 106, 1035-1045. doi:10.1097/01.anes.0000265165.06760.c2

- Leighton, B.L. and Halpern, S.H. (2002) The effects of epidural analgesia on labor, maternal, and neonatal outcomes: A systematic review. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology, 186, 69-77.

- Chestnut, D.H. (1997) Does epidural analgesia during labor affect the incidence of cesarean delivery? Regional Anesthesia, 22, 495-499.

- Hopkins, K. (2000) Are Brazilian women really choosing to deliver by cesarean? Social Science and Medicine, 50, 725-740. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00480-3

- Osis, M.J., Pa’dua, K.S., Duarte, G.A., Souza, T.R. and Faundes, A. (2001) The opinion of Brazilian women regarding vaginal labor and cesarean section. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 75, S59-S66. doi:10.1016/S0020-7292(01)00518-5

- Okonkwo, N.S., Ojengbede, O.A., Morhason-Bello, I.O. and Adedokun, B.O. (2012) Maternal demand for cesarean section: Perception and willingness to request by Nigerian antenatal clients. International Journal of Women’s Health, 4, 141-148.

- Wang, W., Wen, R., Chen, L., Li, L. and Cheng, Y. (2011) The analysis on tendency and influential factors of Cesarean Section rate in 2002-2009 in Bao’an, Shenzhen. Chinese Maternity and Child Health, 14, 2103-2105.

- Lumbiganon, P., Laopaiboon, M., Gulmezoglu, A.M., Souza, J.P., Taneepanichskul, S. and Ruyan, P. (2010) Method of delivery and pregnancy outcomes in Asia: The WHO global survey on maternal and perinatal health 2007-08. Lancet, 375, 490-499. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61870-5

- Hill, Z., Tawiah-Agyemang, C., Manu, A., Okyere, E. and Kirkwood, B.R. (2010) Keeping newborns warm: Beliefs, practices and potential for behaviour change in rural Ghana. Tropical Medicine & International Health, 10, 1118- 1124. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02593.x

- Furness, P.J., McSeveny, K., Arden, M.A., Garland, C., Dearden, A.M. and Soltani, H. (2011) Maternal obesity support services: A qualitative study of the perspectives of women and midwives. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 11, 69. doi:10.1186/1471-2393-11-69

- Heslehurst, N., Moore, H., Rankin, J., Ells, L.J., Wilkinson, J.R. and Summberbell, C.D. (2011) How can maternity services be developed to effectively address maternal obesity? A qualitative study. Midwifery, 27, 170-177. doi:10.1016/j.midw.2010.01.007

- Chang, S., Kenney, N.J. and Chao, Y.Y. (2010) Transformation in self-identity amongst Taiwanese women in late pregnancy: A qualitative study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 47, 60-66. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.06.007

- Schneider, Z. (2002) An Australian study of women’s experiences of their first pregnancy. Midwifery, 18, 238-249. doi:10.1054/midw.2002.0309

- Burnard, P., Gill, P., Stewart, K., Treasure, E. and Chadwick, B. (2008) Analysing and presenting qualitative data. British Dental Journal, 204, 429-432. doi:10.1038/sj.bdj.2008.292

- Burnard, P. (1991) A method of analyzing interview transcripts in qualitative research. Nurse Education Today, 11, 461-466. doi:10.1016/0260-6917(91)90009-Y

- Rosato, M., Mwansambo, C.W., Kazembe, P.N., Phiri, T., Soko, Q.S., Lewycka, S., Kunyenge, B.E., Vergnano, S., Osrin, D., Newell, M. and De L Costello, A.M. (2006) Women’s group’ perceptions of maternal health issues in rural Malawi. Lancet, 368, 1180-1188. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69475-0

- Murray, S.F. (2000) Relation between private health insurance and high rates of caesarean section in Chile: Qualitative and quantitative study. BMJ, 321, 1501-1505. doi:10.1136/bmj.321.7275.1501

- Yoshioka, T., Yeo, S. and Fetters, M.D. (2012) Experiences with epidural anesthesia of Japanese women who had childbirth in the United States. Journal of Anesthesia, 26, 326-333. doi:10.1007/s00540-012-1328-3

- To, W.K. (2007) A questionnaire survey on patients’ attitudes towards epidural analgesia in labour. Hong Kong Medical Journal, 13, 208-215.

- Schaffer, M.A. and Lia-Hoagberg, B. (1997) Effects of social support on prenatal care and health behaviors of low-income women. JOGNN, 26, 433-440. doi:10.1111/j.1552-6909.1997.tb02725.x

- Feng, X., Xu, L., Guo, Y. and Ronsmans, C. (2012) Factors influencing rising caesarean section rates in China between 1988 and 2008. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 90, 30A-39A. doi:10.2471/BLT.11.090399

NOTES

*Conflicts of interest: We do not have any conflicts of interest.

Funding: We do not have any sources of funding for our research.

Ethical approval: This research project was approved by Research Ethics Committee of Bao’an Maternity and Child Health Hospital.