Health

Vol.4 No.12A(2012), Article ID:26111,9 pages DOI:10.4236/health.2012.412A215

Community-based obesity prevention initiatives in aboriginal communities: The experience of the eat well be active community programs in South Australia

![]()

1Nutrition and Dietetics, Flinders University of South Australia, Adelaide, Australia; *Corresponding Author: annabelle.wilson@flinders.edu.au

2Discipline of Public Health, Flinders University of South Australia, Adelaide, Australia

3Obesity Prevention and Lifestyle, Health Promotion Branch, SA Health, Government of South Australia, Adelaide, Australia

4Health Care Management, Flinders University of South Australia, Adelaide, Australia

Received 5 November 2012; revised 10 December 2012; accepted 16 December 2012

Keywords: Obesity Prevention; Aboriginal; Community-Based Intervention; Indigenous; Qualitative

ABSTRACT

Childhood obesity is a growing concern worldwide, and obesity rates are higher in certain groups in the developed world, including Australian Aboriginal people. Community-based obesity prevention interventions (CBOPI) can help to address obesity, however the approach of such programs to reach diverse groups, including Aboriginal people, must be considered. This paper considers one mainstream1 CBOPI, the eat well be active (ewba) Community Programs in South Australia, which was delivered in two communities and sought to reach Aboriginal people as part of the overall program. This paper considers how well this approach was received by the Aboriginal people living and working in those communities. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with nine Aboriginal workers who had some connection to the ewba program, and seven ewba project staff. Qualitative data analysis was performed and factors found to affect how well the program was received by Aboriginal people include relationships, approach and project target group, including geographical area. A different response was observed in the two communities, with a more positive response being observed in the community where more relationships were developed between ewba and Aboriginal staff. For any CBOPI seeking to work with Aboriginal (or other Indigenous) communities, it is vital to consider and plan how the program will meet the needs and preferences of Aboriginal people in all stages of the project, in order to reach this group.

1. INTRODUCTION

The prevalence of childhood overweight and obesity is rising across the world. Ten percent of the world’s schoolaged children are overweight or obese [1] and currently in Australia 25.3% of Australian children, aged 5 - 17 years, are overweight or obese [2].

The risk of obesity is disproportionate across different groups and in developed countries, greater social inequality has been linked to a greater risk of obesity [3]. In Australia, Australian Aboriginal2 people are disproportionately represented in the most disadvantaged groups, experiencing poverty, unemployment, discrimination, challenges with educational outcomes and poor housing disproportionately compared with non-Aboriginal people [4- 6]. It therefore follows that Australian Aboriginal people are at greater risk of obesity. This is reflected in the statistics, with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women one and a half times more likely to be overweight or obese than non-Indigenous women [7] and a higher proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people aged over 15 years and over reporting that they were overweight or obese (57%) compared with the non-Aboriginal population (54%) [7]. South Australian data indicates that a significantly greater proportion of four year old Aboriginal children were overweight or obese in 2009 compared with their non-Aboriginal peers (27.9% and 18.3% respectively) [8].

While there has been an increase in children’s consumption of non-core foods over the past 20 years [9] and a decline in physical activity in defined contexts such as active transport and school physical education [10], it is acknowledged that there is no one single cause of obesity, and that individual behavior alone cannot explain the rising levels [11,12]. An “obesogenic environment”, which refers to political, sociocultural, physiccal and economic factors in an individual or community’s micro or macro environment that promote obesity has been described [11]. In order to consider these multiple contributing factors, there has been a movement away from individualfocused programs [13] towards societal or community level interventions [14,15]. Known as community-based obesity prevention interventions (CBOPI), these programs are usually aimed at children and their families and represent a whole of community approach to effect changes in macro and micro elements of all environmental domains [11].

Considering the disproportionate risk of obesity previously outlined, addressing equity in CBOPI is important. A systematic review of interventions to prevent obesity in children identified that study and evaluation designs need to be strengthened in the area of equity [16]. Considering the disproportionate disadvantage and obesity prevalence in Australian Aboriginal people compared with non-Aboriginal people in Australia, strengthening programs to better reach Aboriginal people is related to equity and is therefore important.

A review of Australian literature indicated that there are few CBOPI that work exclusively with Aboriginal people; however a number of approaches to working with Aboriginal communities were identified. One CBOPI worked with the whole community but had a specific program stream for working with Aboriginal people [17, 18]. Two others were dedicated solely to working with one specific Aboriginal community [19,20]. The most common approach is for programs to work with the whole community and try to involve Aboriginal people along the way. This approach was used by the eat well be active Community Programs in South Australia, a CBOPI implemented in two communities in South Australia from 2005-2010 that sought to contribute to the healthy weight of children and young people through key messages about healthy eating and physical activity across a variety of settings, using a variety of strategies [21]. Internationally, programs exist that address obesity in children in a community setting. A number have been delivered specifically with North American Indian children [22,23] while another has made specific attempts to work with Maori families in New Zealand [24].

Clearly, there is a lack of evidence about CBOPI in Australian Aboriginal people and Indigenous people across the world. This is supported by other research that found a lack of evidence about the effectiveness of interventions to address obesity for Indigenous groups [25]. Considering the higher prevalence of overweight and obesity in Australian Aboriginal people compared to the general population, this is of concern. The purpose of this paper is to consider how the eat well be active Community Programs, a mainstream CBOPI, was received by the Aboriginal communities where the program was based.

2. METHODS

Ethics approval was received from the Flinders University Social and Behavioural Research Ethics Committee, the SA Health Human Research Ethics Committee and the ethics committees of the Aboriginal Health Council of South Australia and the Department of Education and Children’s Services.

2.1. Background to ewba

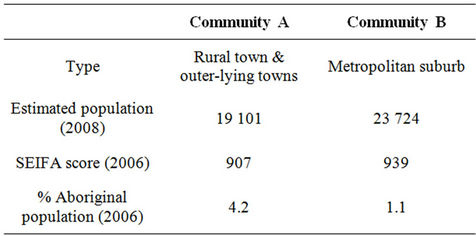

The primary goal of the ewba Community Programs was to contribute to the healthy weight of children and young people (aged 0 - 18) in two communities in South Australia (SA), Community A3 and Community B4 [21]. The characteristics of these communities are shown in Table 1. These two communities were chosen for ewba because of the presence of existing health system infrastructure, high populations of children, low socioeconomic status and the higher proportion of people identifying as Aboriginal, compared to 1.2% in SA overall in 2006 [26]. Socioeconomic status was measured by the Australian Bureau of Statistics using the Socio-Economic Index for Areas (SEIFA) Index of Relative Socio-Economic Disadvantage (IRSD) which focuses primarily on disadvantage and is derived from Census variables including low income, low level of education and unemployment [27].

The key messages, strategies and settings of ewba have been reported elsewhere [21,28,29]. Indigenous agencies were one setting in which the program was implemented. Importantly, Aboriginal people were never intended to be the major group reached through ewba. Even though the higher proportion of Aboriginal people in Community A was a factor in its selection, ewba workers identified that the numbers of Aboriginal people in both communities would have been too low for them to be a major focus. Based on key documents [12,14,15,30], the ewba

Table 1. Characteristics of community A and community B, sites for the eat well be active community programs [21,26,27].

Guiding Principles were developed by SA Health and represented the project values and provided a framework and focus throughout the project. These included the principles that the project would be “inclusive and respectful of Aboriginal communities”, and “equitable” (i.e. reaches all parts of the community where possible, especially the disadvantaged) [21]. Therefore it is clear that while ewba was a program with a whole of community approach, reaching the Aboriginal community was an important part of the project brief.

2.2. PhD Project

The research investigating the question addressed in this paper was a PhD study that was located within the ewba Community Programs.

2.2.1. Theoretical Framework

This research used a social constructionist epistemology which states that reality is experienced, or constructed, by the individual [31]. Consequently, there is no one true, valid interpretation of reality because meanings emerge from people’s interactions and experiences [32]. This is relevant because in this research, the views of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal health professionals were sought, without any judgement about which were more “correct”. The theoretical perspective that informed this research was a critical approach, which is concerned with moving beyond the dominant values of society and identifying the structures that influence what happens on the surface of social reality [33,34]. Methodologies used in the research were reflexivity [35] and critical social research [36].

2.2.2. Values and Ethics to Guide Research with Aboriginal Communities

The research was guided by the National Health and Medical Research Council’s values and ethics for doing research with Aboriginal communities [37], specifically the principles of equality, respect, responsibility, reciprocity, survival and protection and spirit and integrity. Examples of strategies to uphold these values included working with Aboriginal mentors, attending community events regularly to get to know local Aboriginal people and activities of reciprocity (giving back) based on what was requested by the community.

2.2.3. Data Collection

Semi-structured interviews were undertaken in 2010 with ewba staff and Aboriginal workers working in Community A or Community B who had some connection to ewba. Interview schedules were developed by the researcher based on time spent working with Aboriginal communities and these were reviewed and minor alterations were made by Aboriginal project mentors. Ewba staff and Aboriginal workers were recruited by approaching them in person. Relationships were built with Aboriginal workers before interviews occurred to ensure greater trust. Interviews were transcribed verbatim and participants were invited to review their transcript.

2.2.4. Data Analysis

Transcripts were imported into QSR NVivo 8.0 (QSR International, Doncaster, Victoria, 2008). Data were coded into themes and connections between themes were identified, with quotes to demonstrate relevant points, guided by deconstruction and reconstruction, an element of critical social research [36].

3. RESULTS

3.1. Sample

Nine (six from Community A and three from Community B) Aboriginal workers (Aboriginal people working in the health sector at multiple levels, some of whom were Aboriginal health workers) and seven ewba staff (one manager and six project coordinators, three from each community) participated in an interview. Interviews ranged from 20 to 90 minutes.

3.2. Program Consultation

Ewba staff and Aboriginal workers talked about the consultation that occurred with Aboriginal people when planning for the ewba intervention, after the program had started. It did not arise in interviews what consultation took place with Aboriginal people in the very early, planning phase of ewba, prior to selecting the communities. Ewba staff described how they consulted with the Aboriginal community in Community A and B at the start of ewba, as part of the wider ewba consultation. Consultations were set up by approaching Aboriginal health managers at each site, who suggested key people in the community to consult with. In Community A, existing, close working relationships between community members and Aboriginal workers meant that a single consultation was possible with both groups of people commenting alongside each other. This consultation ran relatively smoothly where a community discussion was attended by various stakeholders and facilitated by the manager of the Aboriginal health service. In contrast, in Community B a number of separate consultations were held and they posed more of a challenge. Difficulties in identifying a specific Aboriginal community in urban Community B led to a wider and longer search for appropriate people with whom to consult but at this stage, did not lead to changes in the project’s geographical boundaries. Four consultations eventuated, including one with a local women’s group, one at a community lunch, one with youth and one with workers and community members.

Barriers to consultation were identified by ewba workers in interviews and these included an unrealistic timeframe which was not conducive to building the kind of relationships required for this client group, the need to consult with multiple community groups (not just the Aboriginal community) and the awkwardness of some of the consultations in Community B which was attributed to the lack of trust relationships that had been created between ewba staff and Aboriginal workers.

3.3. Program Awareness

Aboriginal workers were asked about their awareness of the program (whether they knew about ewba and what they knew).

One of nine Aboriginal workers interviewed was able to state that ewba was about “working with the local community about healthy lifestyles and healthy eating” (AW6)5. Other participants’ awareness of ewba was demonstrated by associating it with a key worker, one worker stated that “they’ll get to know you [worker] more than they’ll know about the project” (AW1). Interestingly, some Aboriginal workers had heard the name “eat well be active” but they did not know what it was: “I’ve heard about eat well be active but what does it mean?” (AW1). This was reiterated by a ewba project officer who reflected on her role at a local community event:

…There were lots and lots and lots of comments from people about how good the food was and how nice it was to have fresh [fish] and stuff like that and how I guess it added to the enjoyment to the day but nobody would have had any idea that that was because I stood there and chopped salad for three hours. They would just remember it as the year where they had the barbeque instead of hot dogs. It would not be attributed to anybody’ (EWBA5)6.

Confusion with other SA Health healthy weight initiatives being run in the same communities, often also branded with the term “eat well be active”, was also identified by Aboriginal workers and this confusion was compounded by the fact that the ewba Community Programs were part of a wider Eat Well Be Active Healthy Weight Strategy.

3.4. Program Accessibility

Aboriginal workers and ewba staff were asked how easy it was for the Aboriginal community to access ewba.

Three of the six Aboriginal workers from Community A said the ewba program had been accessible for the Aboriginal community in their location. Specifically, they said that the way ewba workers worked in partnership with the Aboriginal workers assisted with making it accessible (AW6; AW7). However, it was suggested that the changeover of staff interfered with accessibility of ewba to this community as there were periods when there was no staff member (AW7).

Two ewba workers said that ewba was accessible to everybody in the two sites (EWBA1; EWBA6). One worker identified that perhaps it was less accessible to the Aboriginal community in Community B compared with Community A (EWBA2).

3.5. Program Impact

Aboriginal workers and ewba staff were asked whether ewba had had an impact on local Aboriginal people; that is who they thought was impacted by ewba and how.

In general, Aboriginal workers felt that ewba was a positive program (AW3), had provided “overwhelming support” to the local Aboriginal health team and responded to their needs (AW5). In Community A, Aboriginal workers felt that ewba could not have done anything more to make the program suitable (AW3; AW6). Similarly, overall ewba project coordinators indicated that ewba had a positive impact (EWBA4) in the Aboriginal community, however they identified that this impact was small (EWBA6), localized (EWBA6) and generally, indirect (EWBA5). On the other hand, a different ewba worker did not think that ewba had an impact on the lives of Aboriginal people in Community B because of the lack of extensive relationships with members of the Aboriginal health team (EWBA3).

| 6Codes used to deidentify participants from interviews, EWBA=ewba worker. |

Ewba staff generally perceived a greater impact in the Aboriginal community in Community A compared to Community B. In Community B, the most impact was thought to have occurred in the latter stages of the project (EWBA6) to specific groups involved in the project i.e. Aboriginal mothers and their babies. This supports the opinions of Aboriginal workers in Community B who identified this same group as primarily being impacted by the program. Ewba staff indicated these impacts in Community B were the direct result of a relationship with one Aboriginal Health Worker. On the other hand, impacts in Community A were reported in a number of groups by ewba workers, including Aboriginal families with children attending the local kindergarten, primary school students, Aboriginal workers and the wider community. Aboriginal workers in Community A also identified impacts on primary school children attending a cooking program for Aboriginal children, Aboriginal workers, women and the wider community through healthy catering at local events:

I think one of the biggest examples of major change has been watching over the last few years events that we’ve [previously] run with fatty sausages and hamburgers. I think if it wasn’t for eat well be active and the help with that I mean that has ripple effects like you wouldn’t believe; like people are realizing that they have got to start rethinking their diets… (AW7)

Similar to ewba workers, Aboriginal workers in Community A discussed more impacts and in greater detail. For example, three ewba interventions were identified by Aboriginal workers in Community B (including locating and applying for grants, provision of baby packs for new mums and a talk about healthy eating at the local “Mum’s N Bub’s” while eight were identified by Aboriginal workers in Community A (for example support for a women’s cooking group, provision of culturally appropriate cookbooks, assistance with forming a strategic plan around healthy eating and physical activity for the Aboriginal health service and provision of planter tubs and pura taps).

This difference in impact could be partly explained by the development of more extensive, good working relationships and trust between Aboriginal workers and ewba staff in Community A:

…Everybody is trusting of the eat well be active program now so you know, we don’t hesitate about who to contact about healthy catering and healthy things and all that kind of stuff, we just go straight to you guys so it’s fantastic (AW6).

Aboriginal workers from Community A discussed why ewba had a positive impact in their community, including the approach of ewba staff which was to seek out the relevant Aboriginal workers and what they could help with, rather than saying “this is what we do” (AW6, AW7). Focusing on the local community and their needs rather than assuming that the needs of all Aboriginal communities are the same, close working relationships with Aboriginal workers, a commitment to identifying local issues and transparency and a commendable passion in some workers were other reasons provided.

Discussion with ewba staff and Aboriginal workers revealed that the geographical site of Community B did not provide a meaningful boundary for the purposes of identifying and working with the surrounding Aboriginal community. As outlined, Community B was a suburb within a larger local government area in metropolitan Adelaide. The Aboriginal community in the local area was not defined by the chosen suburb but encompassed a much larger suburban area (beyond the bounds of the local government area):

…The issue here is our identification of Community B and this has come up quite a bit in terms of our project having borders around Community B and Aboriginal Community here not having those borders… (EWBA2)

This posed a challenge for consultation and implementation of ewba, for example engaging with the local Aboriginal health team was difficult because this team had a mandate to serve an area much wider than the suburb of Community B. One Aboriginal worker reported that this was communicated to the ewba team during consultation (AW5). Interviews with ewba staff indicated that this was acknowledged by the ewba team, and concluded that at that point in time the communities had already been chosen and higher level management had not foreseen this difficulty when planning the project.

Furthermore, ewba staff reported that the number of Aboriginal people living in Community B was very small and were difficult to identify and contact:

The Aboriginal community was really hard just to find… [ ] …the Community B Aboriginal community, according to ABS [Australian Bureau of Statistics], was very, very small, according to the Aboriginal staff here at the health service, even smaller… [ ] …they were impossible to find let alone work with, it was just like “well who are we going to work with? We want to work with the Aboriginal community but who are they and where do we find them? (EWBA7).

While ewba staff did attempt to work with Aboriginal people from Community B through other agencies such as schools, these experiences meant that ewba workers tended to be disheartened about working with the Aboriginal community before they even started. Whilst the pressure to stay within community boundaries from the funding organisation was identified by ewba staff as high in the early phases of the project, when interviewed in 2010, ewba workers reported that over time they began to broaden the area within which they targeted Aboriginal people in Community B. That is, they took a more regional approach rather than just focusing on the one suburb. They reported this was because “we soon realized that we were never going to be able to target only [the Aboriginal people in] Community B” (EWBA7). For example, sometime into the project the catchment area was broadened to include a kindergarten for Aboriginal children in a nearby suburb. This was not considered ideal, especially for evaluation purposes, as the kindergarten was in a suburb that was acting as a comparison site for evaluation purposes. Similarly, the 0 - 18 years old target group meant that key Aboriginal organizations working with a different age group could not be a site for project activities, such as an organisation that worked with Elder Aboriginal people in Community A (EWBA5).

4. DISCUSSION

This paper explores how the approach of a mainstream CBOPI, seeking to work with Aboriginal communities as part of its wider strategy, was received by Aboriginal people in two communities. This is important, considering the call for equity to be considered in CBOPI [16]. The experience of the ewba Community Programs has indicated that being regardful of Aboriginal peoples’ and communities’ needs and preferences when planning and delivering CBOPI is important. Some of the ways in which these needs and preferences can be supported are through relationships, approach, flexibility and critically considering the concept of a “target” group.

The importance of relationships when working with Aboriginal communities was identified through the more positive response from Aboriginal people in Community A, where ewba staff built more relationships. Relationship building has been identified as vital to working with Aboriginal communities [38] including in CBOPI [17], where the need for mainstream organizations to learn how to build relationships with Aboriginal organizations has been highlighted [19]. In fact, it has been identified that a significant difference to Aboriginal health can only be made if Aboriginal peoples’ voices, opinions and knowledge inform the project [39]. Building good relationships enables staff to work in partnership, and working in partnership with communities and Elders has been identified as vital [22,23,40,41]. Focusing on developing a partnership implies a mutual benefit to both parties and is also about reciprocity [37]. Other projects have sought to work in partnership by, for example, employing Aboriginal staff [18]. However, it is acknowledged that relationship building takes time [19], and Government funded programs such as ewba are often under pressure to meet timeframes. Working in partnership with Aboriginal people is also about trust, and with trust comes responsebility to respond to concerns and work in an appropriate manner [37]. While broadening the boundary of Community B when the concerns were first identified at the consultation could have been an ideal strategy because of the apparent long lasting effects on the relationship with that community, it may not have been feasible in the context and time frames of the Government determined priorities. However, presentation of the issues highlighted at, for example, this consultation in the context of program principles and/or evidence for best practice may help to highlight to others, including management and funding bodies, why such changes are important. This example highlights the importance of flexibility in programs that include Aboriginal people and communities and where this is not possible, advocating for flexibility.

Approach was identified as an important consideration when working with Aboriginal communities. It was suggested by Aboriginal workers in Community A that members of the Aboriginal community knew the face of the ewba project officer, rather than the name of the project that they worked for. This would suggest that more of a focus on building face-to-face relationships with community members and less of a focus on a project brand is important. While this would also address a comment on the confusion of the term “eat well be active” because of multiple initiatives with that name, importantly this was a deliberate strategy by SA Health to create the sense of a common theme across a range of initiatives that included different activities and the confusion identified by Aboriginal workers in this study was an unintended consequence. Aboriginal people working in Community A also identified characteristics in the ewba workers they worked with that contributed to a good approach. These workers naturally engaged in strategies that considered the needs and preferences of Aboriginal people. Aboriginal workers talked about the willingness of ewba workers to work with Aboriginal health workers, their passion and willingness to identify local issues. Previous work has identified the importance of working with Aboriginal people [42-48], the importance of getting to know someone before direct questioning [42,47] and the importance of considering a person’s context when working with them [48]. Other strategies that have also been cited as important when considering the needs and preferences of Aboriginal people in a program include developing and using culturally specific tools [22], integrating Aboriginal ways of learning or knowing [22,23,40,49,50] and consideration of the cultural safety of participants [18].

The notion of a “target group” was also raised in this research, and this has implications for future CBOPI and similar programs. The ongoing difficulties of working with Community B as a suburb rather than an entity that was considered a “community” by local Aboriginal people are clearly demonstrated here. The Aboriginal people in the area did not identify as coming from that particular suburb, and the geographical boundary meant that family members in outerlying suburbs could not be involved. Similarly, having a certain age group target (0 - 18 years old) excluded important Aboriginal people in both communities, such as Elders, who may have influence in the community. It has previously been documented that health professionals need to recognize the importance of family and community to Aboriginal people [51], hence involving family and community as much as possible is important. When considering program approach in the context of equity, whether the geographical area that the program serves is potentially exclusive, and whether flexibility in boundaries might be required to maximize engagement with children in the community in most need, could be considered. Working with funding bodies to determine what is and is not negotiable at the start of the project, and how Government determined priorities can best complement community-identified issues, is important. The use of specific age target groups could also be critically considered and potential benefits weighed against the potential risks outlined here.

It is important to discuss the PhD project in the context of the ewba project. The PhD began in 2008, two years after the ewba intervention. The PhD Candidate (AW) was a member of the ewba team and much of the connection between ewba and the Aboriginal communities after 2008 was facilitated by the PhD Candidate. Consequently the influence of the research topic and presence of the PhD Candidate on the amount of intervention done with Aboriginal communities must be considered. As highlighted, a decision occurred later in the project to widen the boundaries of ewba beyond Community B. From interviews, informal discussions with ewba staff, and observation it appears that discussions about broadening the boundaries of Community B began soon after difficulties with engaging the Aboriginal community were experienced. However, the actual decision to broaden the area appeared to occur sometime in late 2008, after the PhD research began. This situation suggests that having a person present whose role it is to work on Aboriginal health, helps to bring Aboriginal health to the forefront and to keep it on the agenda for action.

While working with Aboriginal people was not the primary purpose of ewba, the ewba Guiding Principles indicated it was an important part of the project. In the case of ewba, the rationale for engagement with Aboriginal people was partly because of the higher than average population of Aboriginal people in Community A. However, considering the higher rates of overweight and obesity in Australian Aboriginal people, and an equity approach which seeks to give attention to those who suffer the highest disparities in health [52], it would follow that considering how the needs and preferences of Aboriginal people will be met in all phases of a CBOPI from planning to evaluation (not just those with higher than average Aboriginal populations) is vital. This is likely to contribute to ensuring health care is provided that is in line with principles for working ethically with Aboriginal people [37]. This is supported by the more positive experience of ewba in Community A, where the approaches and characteristics of individual ewba workers contributed to an approach that accounted for the needs and preferences of Aboriginal people. This indicates that while guiding principles are important, a further level of commitment at the central planning, funding and administration level of a project would help to support workers to engage with Aboriginal people in a way that meets their needs. One way to take account of the needs and preferences of Aboriginal people in a project is to develop a plan for how this will be done, and involve local Aboriginal community members in all phases of the project.

5. CONCLUSION

This study highlights how the approach of mainstream CBOPI may require adaption to meet the priorities and accepted approaches of Aboriginal communities. Clearly, there is still a lot to learn in the context of Australian health care about how best to support Aboriginal communities to prevent obesity. Modifying mainstream programs may not be the best approach and good consultation, which relies on strong relationships, in the planning stage of the project, could help to identify what and where interventions could be directed and if Aboriginal specific or mainstream approaches are more appropriate to that particular setting.

Other CBOPI and similar programs seeking to work with Aboriginal people in Australia can learn from the experience of ewba. For example, focusing on building relationships and being flexible in project approach are important, as is critically considering the concept of a target group and geographical boundaries. However, while funding agencies such as SA Health are mandated to be inclusive and equitable, they also have Government determined priorities, criteria or restrictions where funds are allocated, time-frames, reporting requirements and other planning processes that can limit the ability of programs to be flexible. Consequently, this can make the kind of flexible delivery and relationship-building preferred by many Aboriginal communities challenging and difficult.

More research is needed in to how equity can be further addressed without leading to further disparity, while still meeting the conditions placed on funding bodies. The experiences and evaluation of the ewba Community Programs can be used to help inform future programs seeking to work with Aboriginal people. As is evident form this research, planning programs that clearly outline how they seek to work with Aboriginal people and what they hope to achieve, and meaningful involvement of Aboriginal communities in the initial planning phases of a project right through to project evaluation, is vital to increase engagement, local ownership, accessibility and acceptability of programs to Aboriginal people.

6. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The eat well be active Community Programs were funded by the Government of South Australia, SA Health and implemented by Southern Primary Health, of Southern Adelaide Health Service, and Murray Mallee Community Health, of Country Health SA. Annabelle Wilson was funded by a scholarship from SA Health in 2008 and an Australia Postgraduate award and “top-up” scholarship from SA Health from 2009-2011.

The researchers would like to acknowledge all of the research participants, in particular the Aboriginal people from Community A and Community B who contributed. AW would like to thank project mentors for their input into this work.

REFERENCES

- Lobstein, T., Baur, L. and Uauy, R. (2004) Obesity in children and young people: A crisis in public health. Obesity Reviews, 5, 4-85. doi:10.1111/j.1467-789X.2004.00133.x

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (2012) Australian health survey—First results 2011-2012. Australian Bureau of Statistics, Canberra.

- Monteiro, C., Conde, W.L., Lu, B. and Popkin, B.M. (2004) Obesity and inequalities in health in the developing world. International Journal of Obesity, 28, 1181- 11866. doi:10.1038/sj.ijo.0802716

- Australian Council of Social Services (1974) Poverty, the ACOSS evidence. Australian Government Publishing Service, Canberra.

- Eckermann, A., Dowd, T., Chong, E., Nixon, L., Gray, R. and Johnson, S. (2006) Binan Goonj: Bridging cultures in aboriginal health. Churchill Livingstone, Sydney.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (2010) The health and welfare of Australia’s aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Australian Bureau of Statistics, Canberra.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (2008) Overweight and obesity in adults, Australia, 2004-2005. Australian Bureau of Statistics, Canberra.

- Spurrier, N.J., Volkmer, R.E., Abdallah, C.A. and Chong, A. (2012) South Australian four-year old Aboriginal children: Residence and socioeconomic status influence weight. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 36, 285-290. doi:10.1111/j.1753-6405.2012.00872.x

- Cook, P., Rutishauser, I. and Seelig, M. (2001). Comparable data on food and nutrient intake and physical measurements from the 1983, 1985 and 1995 National Nutrition Surveys. Australian Food and Monitoring Unit, Brisbane.

- Dollman, J., Norton, K. and Norton, L. (2005) Evidence for secular trends in children’s physical activity behaviour. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 39, 892-897. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2004.016675

- Swinburn, B., Egger, G. and Raza, F. (1999) Dissecting obesogenic environments: The development and application of a framework for identifying and prioritising environmental interventions for obesity. Preventive Medicine, 29, 563-570. doi:10.1006/pmed.1999.0585

- National Obesity Taskforce (2003) Healthy weight 2008 Australia’s future: The national action agenda for children and young people and their families. Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra.

- Catford, J., (2003) Promoting healthy weight—The new environmental frontier. Health Promotion International, 18, 1-3. doi:10.1093/heapro/18.1.1

- World Health Organization (2000) Obesity: Preventing and managing the global epidemic in WHO report technical Series. World Health Organization, Geneva.

- Kumanyika, S.S., Jeffery, R.W., Morabia, A.A., Ritenbaugh, C.C. and Antipatsis, V.J. (2002) Obesity prevention: The case for action. International Journal of Obesity, 26, 425-36. doi:10.1038/sj.ijo.0801938

- Waters, E., de Silva-Sanigorski, A., Hall, B.J., Brown, T., Campbell, K., Gao, Y., Armstrong, R., Prosser, L. and Summerbell, C.D. (2011) Interventions for preventing obesity in children. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 12, CD001871. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001871.pub3

- Trindall, S., Allen, L., Bartel, L., Draws, R. and Trapmas, J. (2007) Report from the “Good for Kids. Good for Life”. Aboriginal Communities Consultation Project—Gaayinggal Maaru Gidhaylaya, Good for Kids Good for Life.

- Trindall, S. and Bell, C. (2008) Good for kids good for life—Equity-Focussed Health Impact Assessment. Good for Kids Good for Life.

- Kelaher, M., Sanigorski, A., Ferdinand, A., Bolton, K. and Waller, C. (2011) Final evaluation report for “Go for your life” Health Promoting Communities: Being active and eating well initiative (HPC: BAEW) Wathaurong Aboriginal Co-operative. University of Melbourne, Melbourne.

- Thompson, K. and Kebisu, R. (2008) Eat well, be Active, healthy kids for life—Badu island. National Nutrition Networks Conference: Good Tucker, Good Health, Alice Springs, 11-14 March 2008.

- Pettman, T., McAllister, M., Verity, F., Magarey, A., Dollman, J., Triptree, M., Stanley, S., Wilson, A. and Mastersson, N. (2010) Eat well be active community programs final report. SA Health, Adelaide.

- Caballero, B., Clay, T., Davis, S.M., Ethelbah, B., Holy Rock, B., Lohman, T.G., Norman, J.E., Story, M., Stone, E.J., Stephenson, L. and Stevens, J. (2003) Pathways: A school-based, randomized controlled trial for the prevention of obesity in American Indian schoolchildren. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 78, 1030-1038.

- LaRowe, T.L., Wubben, D.P., Cronin, K.A., Vannatter, S.M. and Adams, A.K. (2007) Development of a culturally appropriate, hoe-based nutrition and physical activity curriculum for Wisconsin American Indian families. Preventing Chronic Disease—Public Health Research, Practice and Policy, 4, 1-8.

- Rush, E., Reed, P., McClennan, S., Coppinger, T., Simmons, D. and Graham, D. (2012) A school-based obesity control program: Project energize. Two-year outcomes. British Journal of Nutrition, 107, 581-587. doi:10.1017/S0007114511003151

- Ruben, A. (2009) Undernutrition and obesity in indigenous children: Epidemiology, prevention, and treatment. Pediatric Clinics of North America, 56, 1285-1302. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2009.09.008

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (2006) Population distribution, aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, 2006. Australian Bureau of Statistics, Canberra.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (2008) Census of population and housing: Socio-economic indexes for areas. Australian Bureau of Statistics, Canberra.

- Wilson, A., Magarey, A. and Mastersson, N. (2008) Reliability and relative validity of a child nutrition questionnaire to simultaneously assess dietary patterns associated with positive energy balance and food behaviours, attitudes, knowledge and environments associated with healthy eating. International Journal of Behavioural Nutrition and Physical Activity, 5. doi:10.1186/1479-5868-5-5

- Wilson, A., Magarey, A., Dollman, J., Jones, M. and Mastersson, N. (2009) The challenges of quantitative evaluation of a multi-setting, multi-strategy community based childhood obesity prevention program: Lessons learnt from the eat well be active Community Programs in South Australia. Public Health Nutrition, 13, 1262-1270. doi:10.1017/S1368980009991807

- Swinburn, B., Gill, T. and Kumanyika, S. (2005) Obesity prevention: A proposed framework for translating evidence into action. Obesity Reviews, 6, 23-33. doi:10.1111/j.1467-789X.2005.00184.x

- Denzin, N. and Lincoln, Y. (1994) Handbook of qualitative research. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks.

- Crotty, M. (1998) The Foundations of Social Research: Meaning and perspective in the research process. Allen & Unwin, St Leonards.

- Neuman, W.L. (2000) Social research methods qualitative and quantitative approaches. 4th Edition, Allyn & Bacon, Needham Heights.

- Haralambos, M. and Holborn, M. (2004) Sociology themes and perspectives. 6th Edition, Collins, London.

- Etherington, K. (2004) Becoming a reflexive researcher: Using our selves in research. Jessica Kingsley Publishers, London.

- Harvey, L. (1990) Critical Social Research. Unwin Hyman Ltd., Sydney.

- National Health & Medical Research Council (2003) Values and ethics: Guidelines for ethical conduct in aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health research. Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra.

- Pyett, P., Waples-Crowe, P. and van der Sterren, A. (2008) Challenging our own practices in indigenous health promotion and research. Health Promotion Journal of Australia, 19, 179-183.

- Sherwood, J. and Edwards, T. (2006) Decolonisation: A critical step for improving aboriginal health. Contemporary Nurse, 22, 177-190. doi:10.5172/conu.2006.22.2.178

- Paradis, G., Levesque, L., Maucaulay, A.C., Cargo, M., McComber, A., Kirby, R., Receveur, O., Kishchuk, N. and Potvin, L. (2005). Impact of a diabetes prevention program on body size physical activity, and diet among kanien’keha:ka (Mohawk) children 6 to 11 years old: 8- year results from the Kahnawake Schools Diabetes Prevention Project. Pediatrics, 115, 333-339. doi:10.1542/peds.2004-0745

- Smith, L. (1999) Decolonizing methodologies—Research and indigenous peoples. Zed Books Ltd., London.

- Watts, E. and Carlson, G. (2002) Practical strategies for working with indigenous people living in Queensland, Australia. Occupational Therapy International, 9, 277- 293. doi:10.1002/oti.169

- Read, C., (2006) Working with an aboriginal community liaison worker. Rural and Remote Health, 6, 1-9.

- Blackman, R., (2009) Knowledge for practice: Challenges in culturally safe nursing practice. Contemporary Nurse, 32, 211-214.

- Macaulay, A.C., (2009) Improving aboriginal health. Canadian Family Physician, 55, 334-336.

- Smith, D., (2010) Rethinking nursing best practices with aboriginal communities: Informing dialogue and action. Nursing Leadership, 22, 24-39.

- Bennett, B., Zubrzycki, J. and Bacon, V. (2011) What do we know? The experiences of social workers working alongside aboriginal people. Australian Social Work, 64, 20-37. doi:10.1080/0312407X.2010.511677

- Stedman, A. and Thomas, Y. (2011) Reflecting on our effectiveness: Occupational therapy interventions with Indigenous clients. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 58, 43-49. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1630.2010.00916.x

- Daniel, M., Green, L.W., Marion, S.A., Gamble, D., Herbert, C.P., Hertzman, C. and Sheps, S.B. (1999) Effectiveness of community-directed diabetes prevention and control in a rural aboriginal population in British Columbia, Canada. Social Science and Medicine, 48, 815-832. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00403-1

- Saksvig, B., Gittelsohn, J., Harris, S.B., Hanley, A.J.G., Valente, T.W. and Zinman, B. (2005) A pilot school-based healthy eating and physical activity intervention improved diet, food knowledge and self-efficacy for Native Canadian children. The Journal of Nutrition, 135, 2392- 2398.

- Smylie, J. (2000) A guide for health professionals working with Aboriginal peoples—Cross cultural understandings. Journal of the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada, 23, 157-167.

- Braveman, P. and Gruskin, S. (2003) Defining equity in health. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 57, 254-258. doi:10.1136/jech.57.4.254

Abbreviations

CBOPI = Community based obesity prevention intervention;

ewba = eat well be active;

IRSD = Index of Relative Socio-Economic Disadvantage;

SA = South Australia;

NOTES

1The term “mainstream” refers to health services or programs delivered to the entire community, not specifically Aboriginal communities.

2In this paper we use the term “Aboriginal”, unless a source refers directly to “Indigenous” or “Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander”. This research was conducted in South Australia where the Indigenous peoples of the land self-identify as Aboriginal, hence we use this term in consideration of the preference of the Aboriginal people involved in this research.

3This community has been deidentified to maintain confidentiality.

4This community has been deidentified to maintain confidentiality.

5Codes used to deidentify participants from interviews, AW = Aboriginal worker.