American Journal of Plant Sciences

Vol.06 No.08(2015), Article ID:56719,21 pages

10.4236/ajps.2015.68128

Rhombic Analysis Extension of a Plant-Surface Water Interaction-Diffusion Model for Hexagonal Pattern Formation in an Arid Flat Environment

Bonni J. Kealy-Dichone1, David J. Wollkind2, Richard A. Cangelosi1

1Department of Mathematics, Gonzaga University, Spokane, USA

2Department of Mathematics, Washington State University, Pullman, USA

Email: dichone@gonzaga.edu

Copyright © 2015 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 26 March 2015; accepted 24 May 2015; published 27 May 2015

ABSTRACT

An existing weakly nonlinear diffusive instability hexagonal planform analysis for an interaction- diffusion plant-surface water model system in an arid flat environment [11] is extended by performing a rhombic planform analysis as well. In addition a threshold-dependent paradigm that differs from the usually employed implicit zero-threshold methodology is introduced to interpret stable rhombic patterns. The results of that analysis are synthesized with those of the existing hexagonal planform analysis. In particular these synthesized results can be represented by closed- form plots in the rate of precipitation versus the specific rate of plant density loss parameter space. From those plots, regions corresponding to bare ground and vegetative Turing patterns consisting of tiger bush (parallel stripes and labyrinthine mazes), pearled bush (hexagonal gaps and rhombic pseudo-gaps), and homogeneous distributions of vegetation, respectively, may be identified in this parameter space. Then that predicted sequence of stable states along a rainfall gradient is both compared with observational evidence and used to motivate an aridity classification scheme. Finally this system is shown to be isomorphic to the chemical reaction-diffusion Gray-Scott model and that isomorphism is employed to draw some conclusions about sideband instabilities as applied to vegetative patterning.

Keywords:

Tiger Bush, Pearled Bush, Nonlinear Stability, Threshold-Dependent Patterns

1. Introduction

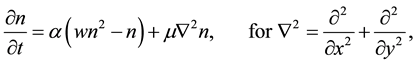

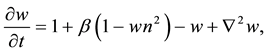

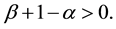

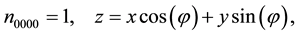

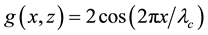

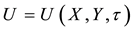

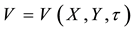

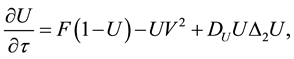

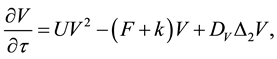

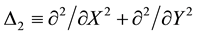

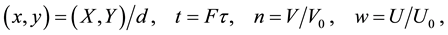

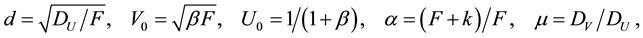

In order to explain more fully the occurrence of tiger bush (or banded thicket) patterns in arid flat environments [1] , Kealy and Wollkind [2] introduced a two-component interaction-diffusion model system based on the Klausmeier [3] differential flow instability model but including the diffusion of surface water rather than its advection. That is, they considered the dimensionless coupled partial differential interaction-diffusion equation model for  plant biomass density and

plant biomass density and  surface water content, where

surface water content, where  a two- dimensional spatial coordinate system and

a two- dimensional spatial coordinate system and  time,

time,

(1.1)

(1.1)

(1.2)

(1.2)

defined on an unbounded planar domain with

. (1.3)

. (1.3)

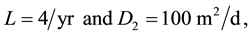

Here A and L are the rates of precipitation and evaporation for the water; R and M, the rates of water infiltration and biomass loss for the plants; J, the yield of plant biomass per unit water consumed; and  and

and , the constant dispersal and diffusion coefficients of the plants and water, respectively.

, the constant dispersal and diffusion coefficients of the plants and water, respectively.

From a linear stability analysis of its possible critical points, Kealy and Wollkind [2] deduced that system (1.1)-(1.2) admitted both a bare ground trivial equilibrium point ( ,

, ) , which existed and was stable for all parameter values, and a homogeneous vegetation community equilibrium point

) , which existed and was stable for all parameter values, and a homogeneous vegetation community equilibrium point  which could generate a Turing [4] -type diffusive instability. They then performed a variety of weakly nonlinear instability analyses on that community equilibrium point finding from a one-dimensional analysis that it bifurcated supercritically to form a stationary striped vegetative pattern and from a two-dimensional hexagonal planform analysis that a close-packed array of vegetative gaps could occur in a narrow region flanking the marginal stability curve in their diffusive instability

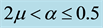

which could generate a Turing [4] -type diffusive instability. They then performed a variety of weakly nonlinear instability analyses on that community equilibrium point finding from a one-dimensional analysis that it bifurcated supercritically to form a stationary striped vegetative pattern and from a two-dimensional hexagonal planform analysis that a close-packed array of vegetative gaps could occur in a narrow region flanking the marginal stability curve in their diffusive instability  parameter space for the typical value of

parameter space for the typical value of  [5] . Finally, Kealy and Wollkind [2] identified these theoretical predictions with tiger and pearled bush patterns, respectively, and compared them with numerical simulations of Klausmeier’s [3] model system. Specifically, they showed that the predicted wavelength of the tiger bush patterns including the width ratio between stripes and interstripes was in very good quantitative agreement with the vegetative bands involving acacia trees in the Go-Gub area of Somaliland [6] . To make this comparison Kealy and Wollkind [2] employed the concept of low threshold patterns, originally introduced by Wollkind and Stephenson [7] and Boonkorkuea et al. [8] , without explicitly specifying the mechanism required to pose the proper threshold value for vegetative biomass associated with that methodology. After Cangelosi et al. [9] , who investigated a model for mussel bed patterning, in order to make this selection process more precise it is necessary for us to extend the weakly nonlinear stability analyses of Kealy and Wollkind [2] by performing a two-dimensional rhombic planform analysis of the community equilibrium point of (1.1)-(1.2) as well.

[5] . Finally, Kealy and Wollkind [2] identified these theoretical predictions with tiger and pearled bush patterns, respectively, and compared them with numerical simulations of Klausmeier’s [3] model system. Specifically, they showed that the predicted wavelength of the tiger bush patterns including the width ratio between stripes and interstripes was in very good quantitative agreement with the vegetative bands involving acacia trees in the Go-Gub area of Somaliland [6] . To make this comparison Kealy and Wollkind [2] employed the concept of low threshold patterns, originally introduced by Wollkind and Stephenson [7] and Boonkorkuea et al. [8] , without explicitly specifying the mechanism required to pose the proper threshold value for vegetative biomass associated with that methodology. After Cangelosi et al. [9] , who investigated a model for mussel bed patterning, in order to make this selection process more precise it is necessary for us to extend the weakly nonlinear stability analyses of Kealy and Wollkind [2] by performing a two-dimensional rhombic planform analysis of the community equilibrium point of (1.1)-(1.2) as well.

As a prelude to that investigation, we summarize the hexagonal planform results of Kealy and Wollkind [2] in Section 2. We perform the rhombic planform nonlinear diffusive instability analysis of the homogeneous vegetative equilibrium point of (1.1)-(1.2) in Section 3. In particular we find that, although square patterns of rhombic angle  are not stable, rhombic patterns of other characteristic angles do occur. In the process we introduce a threshold-dependent paradigm to interpret those stable rhombic patterns that differs from the implicit zero- threshold methodology usually employed for this purpose. We synthesize the results of Sections 2 and 3, in Section 4. These synthesized results can be represented by closed-form plots in

are not stable, rhombic patterns of other characteristic angles do occur. In the process we introduce a threshold-dependent paradigm to interpret those stable rhombic patterns that differs from the implicit zero- threshold methodology usually employed for this purpose. We synthesize the results of Sections 2 and 3, in Section 4. These synthesized results can be represented by closed-form plots in  parameter space for a fixed value of

parameter space for a fixed value of

2. The One-Dimensional and Hexagonal-Planform Results of Kealy and Wollkind [2]

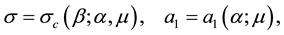

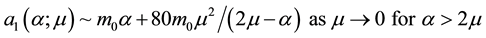

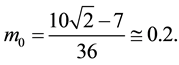

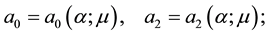

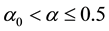

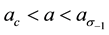

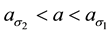

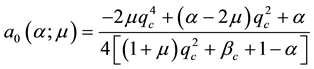

Kealy and Wollkind [2] found that the homogeneous vegetation equilibrium point of (1.1)-(1.2), which existed for

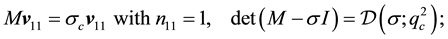

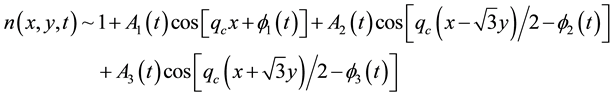

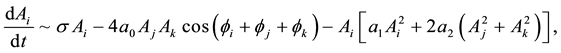

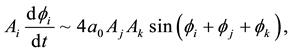

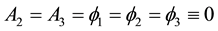

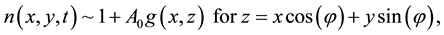

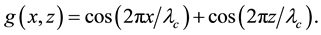

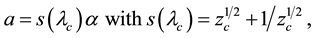

They performed a hexagonal planform analysis of that community equilibrium point of system (1.1)-(1.2) by seeking a solution to it that to lowest order satisfied

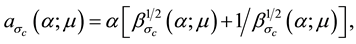

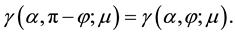

where, for

with an analogous expansion for

Their one-dimensional pattern formation results can be deduced by taking

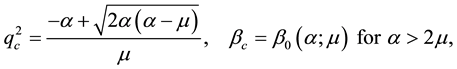

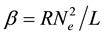

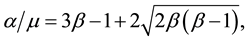

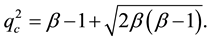

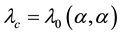

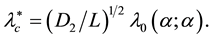

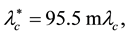

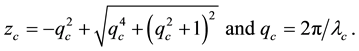

in (2.2) and (2.3)-(2.4). From a linear stability analysis Kealy and Wollkind [2] found that the components of the maximum point of the marginal curve in their wave number squared-bifurcation parameter two-dimensional space were given by

where

with

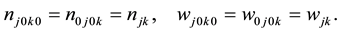

depicted in Figure 1, served as a similar surface in

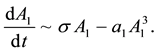

Under the conditions of (2.5), the amplitude-phase equations of (2.3)-(2.4) reduced to the Landau equation

Figure 1. Three-dimensional plots of the marginal stability surface

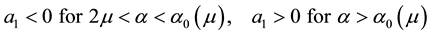

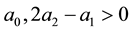

From their one-dimensional nonlinear stability analysis Kealy and Wollkind [2] found that

where

where

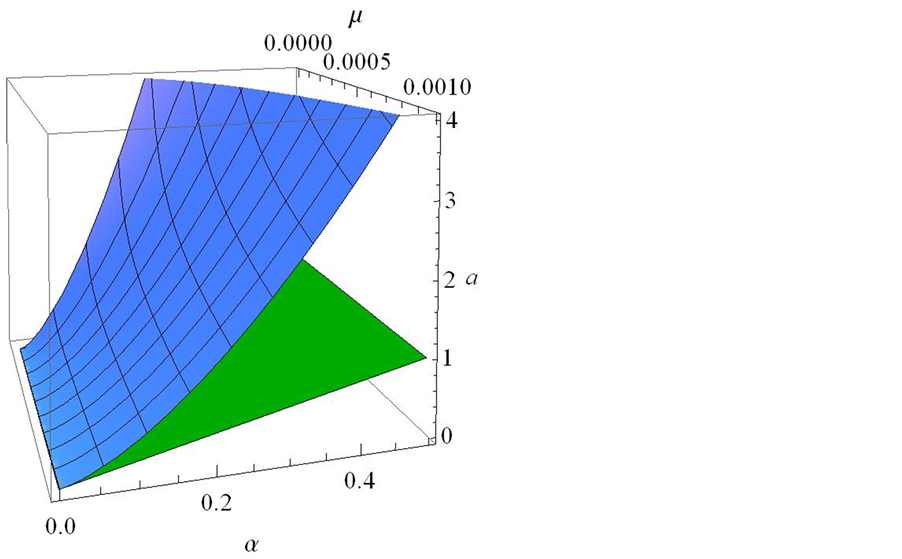

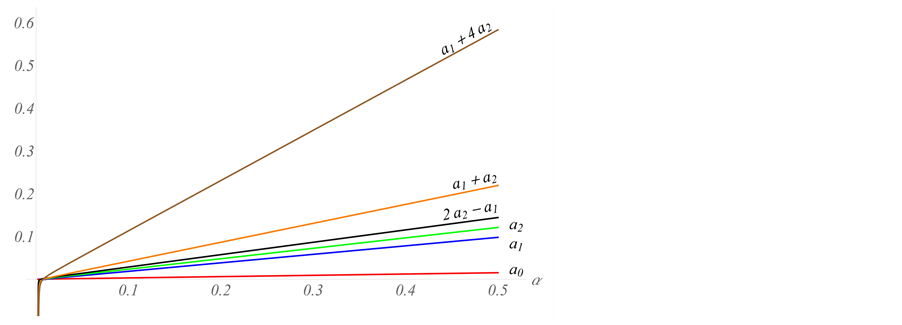

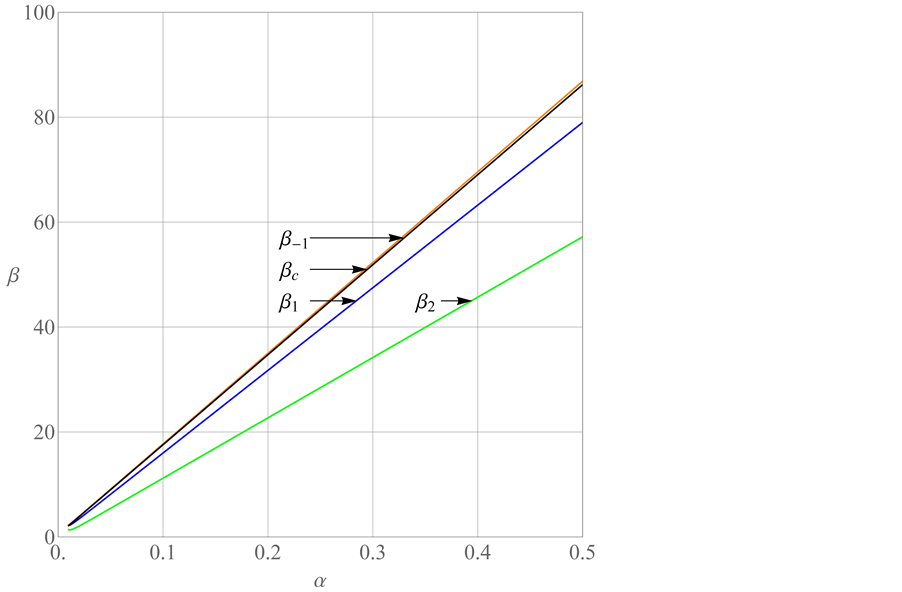

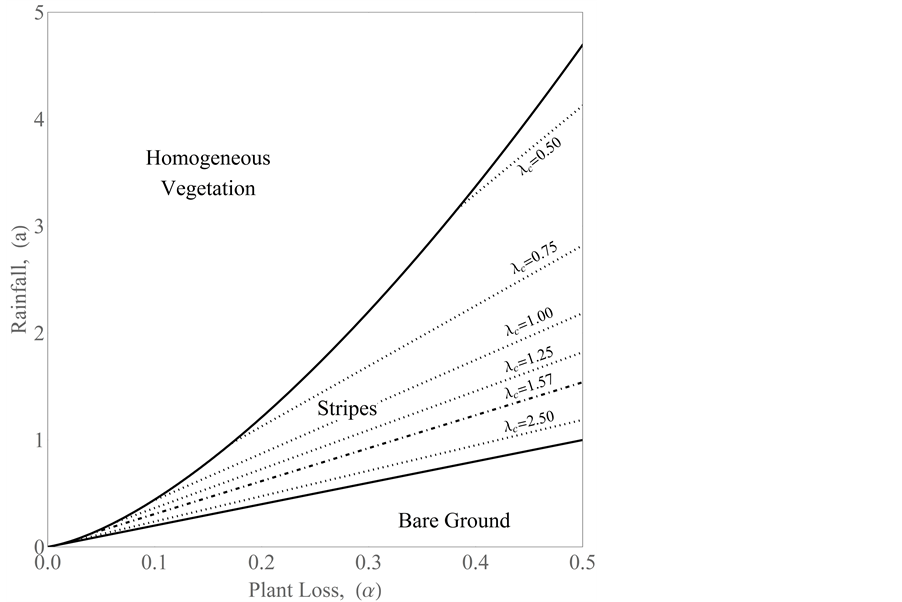

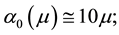

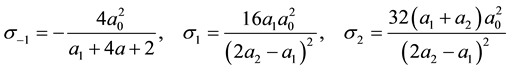

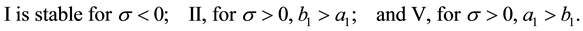

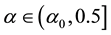

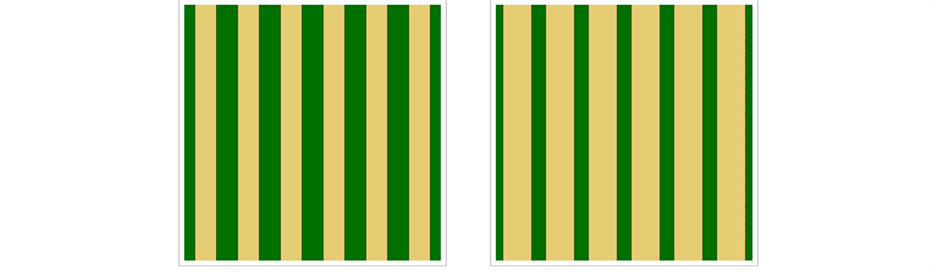

Figure 2 consists of two parts: A left-hand part for which

where

and a linear asymptote of the form

Figure 2. Plots of the Landau constant

parallel vegetative stripes resulted with amplitude

respectively.

The one-dimensional pattern formation results of Kealy and Wollkind [2] are summarized in the

Wishing to refine their one-dimensional pattern formation predictions summarized in Figure 3, Kealy and Wollkind [2] next considered the full two-dimensional hexagonal planform expansions of (2.2) and (2.3)-(2.4). Since

catalogued the critical points of equations (2.3)-(2.4); summarized their orbital stability behavior; and identified the potentially stable ones with various vegetative patterns obtaining the following critical point identifications: I, homogeneous distributions; II, stripes

Kealy and Wollkind [2] first determined that critical point I was stable provided

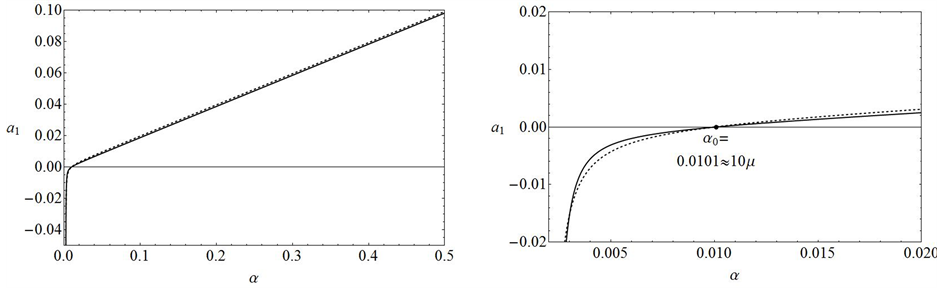

Figure 3. Stability diagram in the

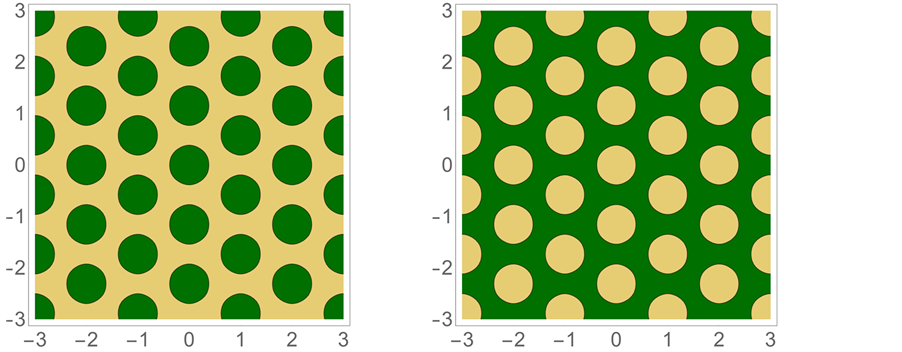

Figure 4. (a) A contour plot of the hexagonal array of spots for

respectively, for

from (2.8)

Figure 5. Plots of

where

We plot these loci along with those of Figure 3 in Figure 6 for

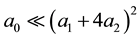

We close this section with the observation that in order to retain only terms through third-order in our expansions of (2.3)-(2.4) its Landau constants must be in the relation [12]

which is satisfied for those quantities as depicted in Figure 5.

3. Two-Dimensional Analysis: Rhombic-Planform Nonlinear Stability Results

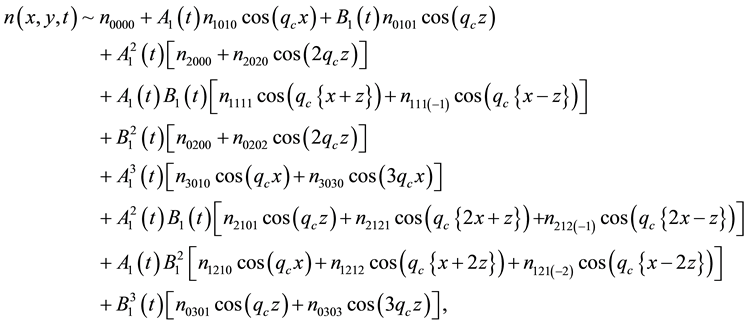

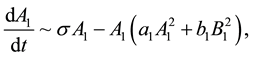

Wishing to refine further the two-dimensional hexagonal planform predictions summarized in Figure 6 and to investigate more precisely the possibility of occurrence of the low-threshold tiger bush patterns observed by Levefer and Lejeune [6] , we next consider a rhombic-planform solution of system (1.1)-(1.2) of the form [7]

Figure 6. Plots of

where

with an analogous expansion for

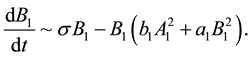

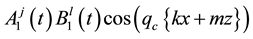

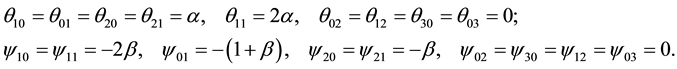

Here we are employing the notation

we define the expansion coefficients

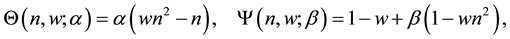

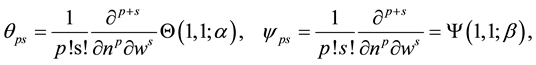

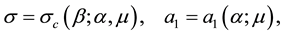

which are tabulated below:

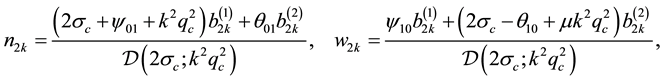

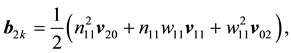

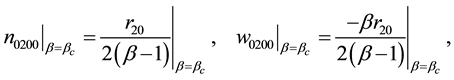

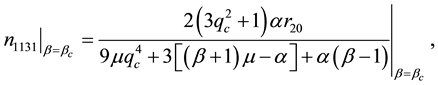

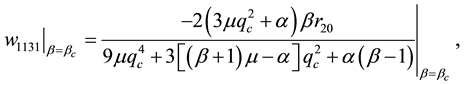

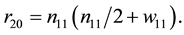

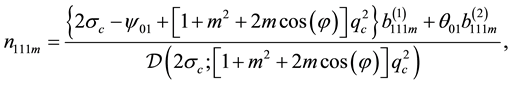

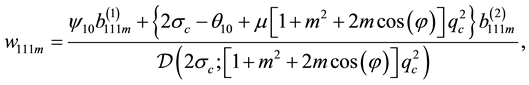

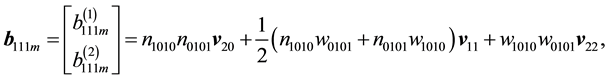

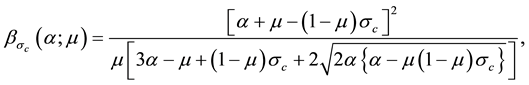

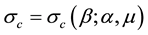

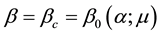

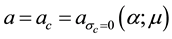

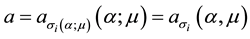

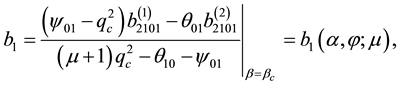

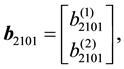

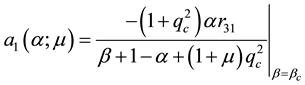

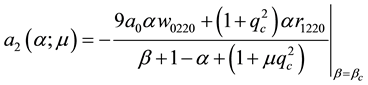

Solving those problems we find that

while applying the same method of analysis, as employed for deducing (A.1) and (A.2), to the

where the components of

as well as the solutions for the relevant second-order systems are catalogued in the Appendix.

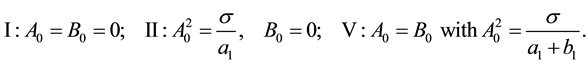

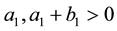

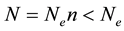

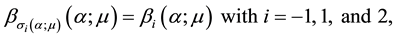

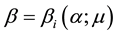

Having developed these formulae for its growth rate and Landau constants, we now turn our attention to the rhombic-planform amplitude Equations (3.3)-(3.4), which possess the following equivalence classes of critical points

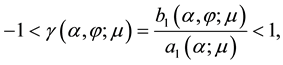

Assuming that

Note that I and II, as in the one-dimensional analysis of the previous section, represent the uniform homogeneous and supercritical banded states, respectively, while V can be identified with a rhombic pattern possessing characteristic angle

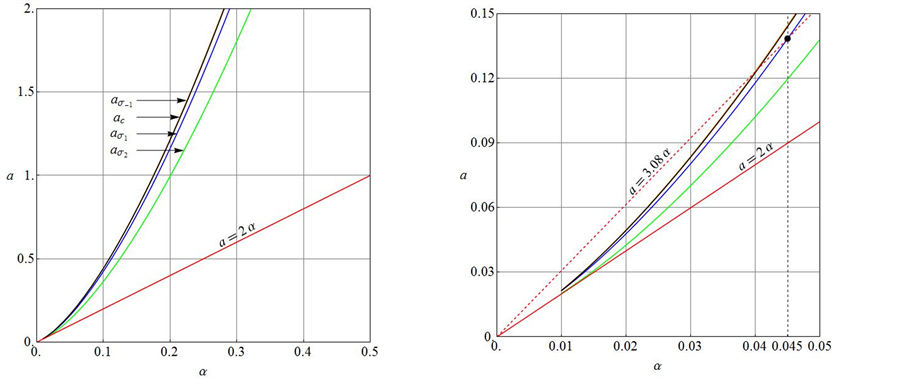

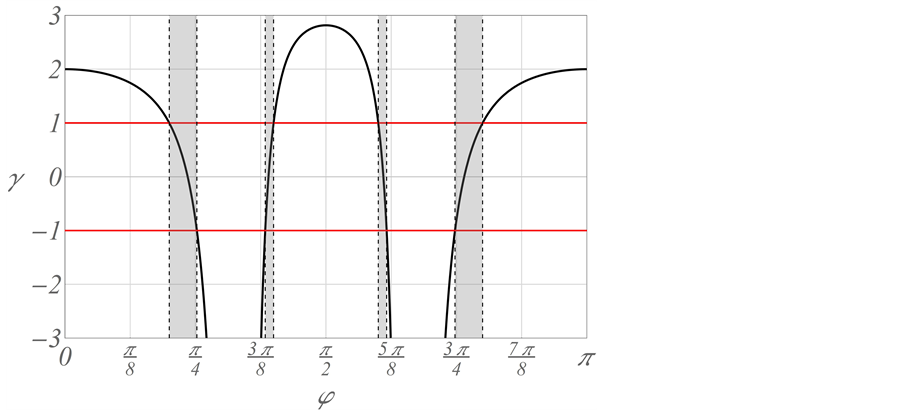

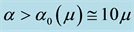

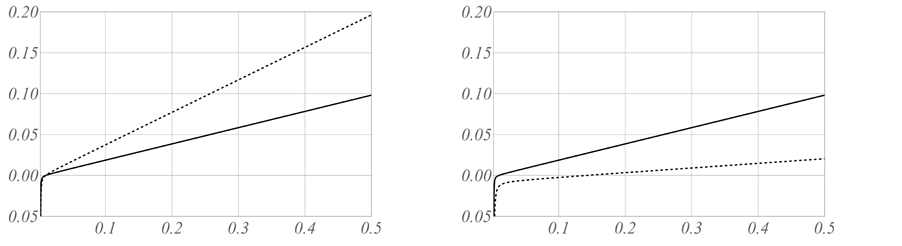

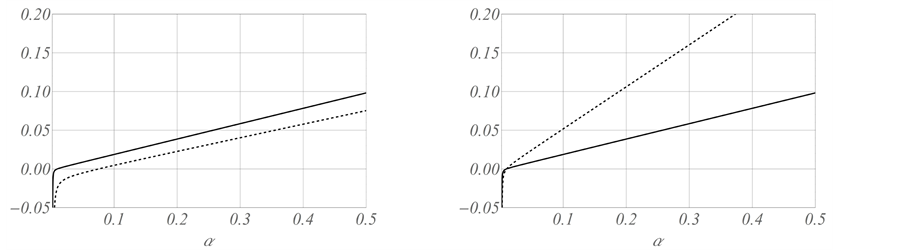

We now use these criteria to pursue those goals stated at the beginning of this section. Toward that end, we first plot

Figure 7. Plots of

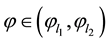

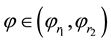

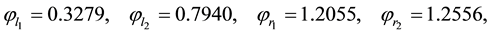

provided, in addition, that

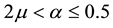

which have been designated by vertical lines. Both of these lie between

which is consistent with Figure 7(a). Also note that this figure has been drawn for the extended interval

Here, properties (3.15) and (3.16) are a consequence of mode interference occurring exactly at

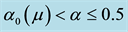

We have deferred until now a detailed morphological interpretation of the rhombic patterns that can be identified with critical point V for the values of the characteristic angle

where

Figure 8. A plot of

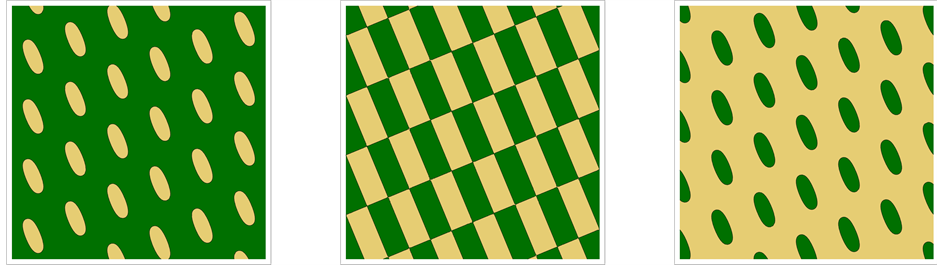

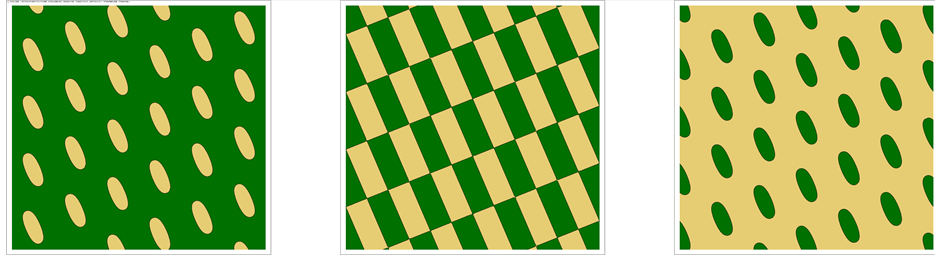

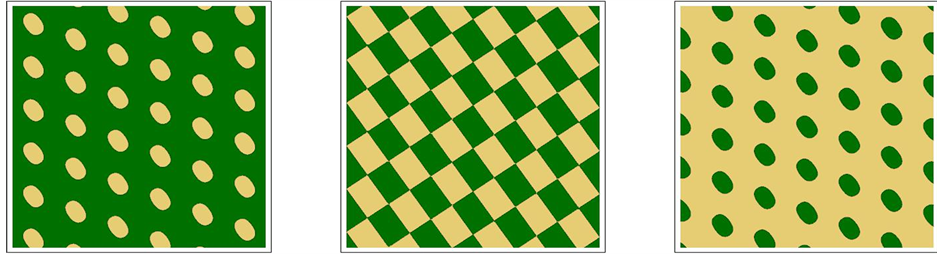

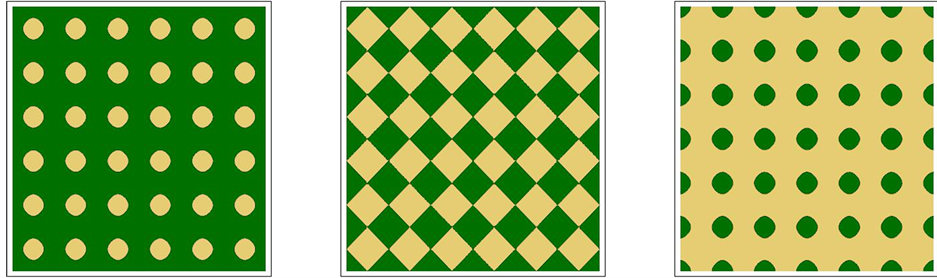

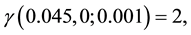

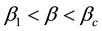

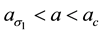

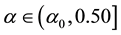

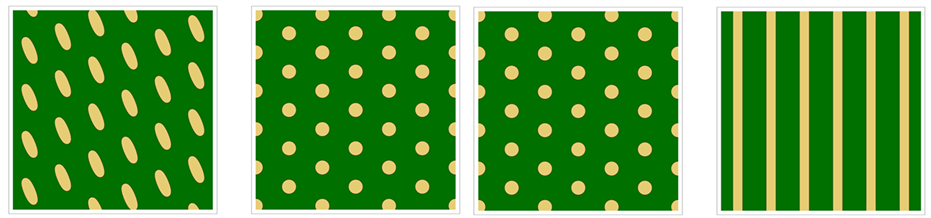

The three parts of Figures 9-12 are threshold contour plots of (3.18) for

Figure 9. Striped patterns relevant to

Figure 10. Rhombic patterns relevant to

Figure 11. Rhombic patterns relevant to

Figure 12. Square patterns relevant to

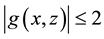

as the threshold to trigger the color change from light to dark (see Figure 4). Thus all spatial regions characterized by

Kealy and Wollkind [2] plotted

adopt the protocol that

4. Synthesis, Aridity Classification Scheme, and Comparisons

We first wish to synthesize the morphological stability predictions summarized in Section 2 and developed in Section 3, respectively. To do so, we begin by considering our rhombic pattern formation results of the latter section in conjunction with the hexagonal pattern formation ones of the former section. Extrapolating from the conclusions of Golovin et al. [16] and Schatz et al. [17] , who demonstrated theoretically and experimentally, respectively, that square patterns only occurred for Marangoni convection with poorly conducting boundaries in the neighborhood of the marginal stability curve where supercritical Bénard cells but not rolls would normally be predicted from a hexagonal planform analysis, we can deduce that our stable rhombic vegetative patterns will only occur in the region of parameter space satisfying

Observe from Figure 6 that the plot of

Figure 13. Plots of the marginal curves of (2.6)-(2.7) and (3.20)-(3.21) versus

The locus

in what follows. Under this simplification the rainfall column of the morphological stability predictions of Table 1 reduces to that of Table 2.

We represent generic versions of these patterns in Figure 14. Here we have made use of the fact that

Kealy and Wollkind [2] compared their theoretical predictions with relevant observational evidence involving periodic self-organized vegetative patterns of tiger and pearled bush occurring in homogeneous ecosystems (reviewed by Rietkerk et al. [19] ). Tiger bush tends to consist of parallel vegetative stripes. When the ground surface slopes, these stripes migrate upslope while when that surface is practically flat static banded vegetation patterns result. Couteron et al. [1] catalogued those differences between these two-types of banded thicket patterns. The static banded states provided good qualitative agreement with tiger bush patterns found in arid flat environments while the upslope migrating stripes predicted by Klausmeier [3] , Sherratt [20] , and Sherratt and Lord [21] provided such agreement with those found in sloping environments. Hence, Wollkind and Kealy [2]

Figure 14. Predicted generic vegetative patterns relevant to Table 3 for (a)

Table 1. Synthesized morphological stability predicitions for Figure 6 and Figure 13.

Table 2. Simplified morphological stability predictions along a rainfall gradient.

identified their parallel stationary diffusive instability stripes with those tiger bush patterns found on plateaus. In order to demonstrate that their model also provided good quantitative agreement with observed tiger bush patterning, they considered Figure 1 of Lefever and Lejeune [6] which is a photograph of regular parallel stripes

Table 3. Aridity classification scheme along a rainfall gradient for

consisting of Acacia bussei trees in the Go-Gub area of Somaliland. These stripes are about 100 m wide while the width of the separating interstripes is about 50m. Thus the dimensional wavelength associated with this pattern is approximately

To compare these predicted pattern wavelengths of (2.15) with this result, they first reformulated the wavenumber expression of (2.6) by solving the marginal stability curve

and then substituting (4.4) into (2.6) found that

Now, employing this formula of (4.5) in (2.15) and making use of the definition of

and

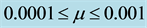

Introducing the evaporation rate and surface water diffusion values from Klausmeier [3] and Rietkerk et al. [5] , respectively,

into (4.6)-(4.7) then yielded

which, upon comparison with (4.3), implied that

Finally, inverting (4.6), Kealy and Wollkind [2] obtained

where

They then used (4.11)-(4.12) to plot lines of various constant wavelength

Recalling that

Figure 15. A reproduction of the

assertion that

Observed from Table 2 and Figure 14, that stripes of this sort, occurring at the upper bound of allowable

We conclude this discussion with an ecological interpretation of the hexagonal close-packed vegetative distribution of gaps and rhombic arrays of pseudo gaps also predicted in the region classified as semiarid in Table 3. Such patterns are generally identified with pearled or spotted bush made up of bare spots uniformly distributed in dense vegetation or vegetative nets within which interior patches of low density occur [8] . In this context, Deblauwe et al. [22] reported a region in Sudan where only gapped and one-dimensional isotropic vegetative patterns occurred with a transition from the former to the latter as rainfall decreased. An occurrence of this sort is consistent with our model’s morphological predictions summarized in Table 3.

We close by discussing our results in relation to those obtained for the Gray-Scott chemical reaction-diffusion model system. Recently, van der Stelt et al. [23] performed a nonlinear stability analysis in the limit of large advection on a one-dimensional version of what they termed a Generalized Klausmeier-Gray-Scott model, which when restricted to Fickian diffusion can be shown to be equivalent to the one treated by Ursino [24] who performed a linear stability analysis of the Klausmeier model including surface water diffusion as well. Further, van der Stelt et al. [23] stated that the nonlinear stability results of Morgan et al. [25] on the one-dimensional Gray-Scott model were strongly related to the corresponding ones of Kealy and Wollkind [2] . To show the

Table 4. Parameter values for acacia trees relevant to tiger bush patterns of wavelength 150 m.

validity of this statement, we first need to consider the Gray-Scott nondimensionalized reaction-diffusion model system [26] for the chemical species

defined on an unbounded planar domain. Here,

where

system (4.14)-(4.15) is transformed into our interaction-diffusion model system (1.1)-(1.2). van der Stelt et al. [23] formulated their Generalized Klausmeier-Gray-Scott model from the traditional Gray-Scott model (4.14)- (4.15) by adding an advection term of the form

to the right-hand side of (4.14) and letting

in (4.15) where E was an unconstrained constant independent of F. Then from (4.17) and (4.19) we can make the identification that

Observe that when

So far we have limited our discussion to analyses for which the wavenumber was restricted to the critical wavenumber of linear stability theory alone. In order to investigate the consequence of considering other wavenumbers in the instability sideband centered about this critical wavenumber, we would need to convert our Landau-type amplitude equations in time to Ginzburg-Landau partial differential equations by adding the appropriate spatial derivative terms to them. That was precisely what Morgan et al. [25] did in their analysis of the Gray- Scott model. In particular for

Note that the parameter values

This condition is certainly satisfied by the ecologically meaningful

When (4.21) is violated, Klausmeier’s [3] nonspatial model can produce limit cycles oscillating about the community equilibrium point or excitable behavior related to the trivial equilibrium point Note that the Gray-Scott model system (4.14)-(4.15) having no parameter restriction of this sort behaves very differently. Thus not all results deduced for that chemical reaction can be directly extended to our ecological interaction.

Finally, recalling that

represents the corresponding equilibrium point of the Gray-Scott reaction-diffusion model system (4.14)-(4.15). Hence from (4.17) and (4.23) we may conclude that

which is equivalent to (3.19).

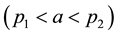

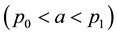

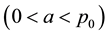

We end by restating von Hardenberg et al.’s [18] contention that the power of model systems such as ours of (1.1)-(1.2) is their predicted sequence of stable states along a rainfall gradient can be used to motivate aridity classification schemes of the sort offered in Table 3 that, in general, can be characterized by three rainfall thresholds

which, when particularized to

Here we are employing the notation of von Hardenberg et al. [18] for these three rainfall thresholds and in Table 3 introduced the following possible aridity classes based upon the inherent vegetative states of our system:

Dry-subhumid

Semiarid

Arid

Hyperarid

As noted by von Hardenberg et al. [18] the utility of the prospective aridity classification scheme is that it allows for future predictions for a dryland region based upon its present vegetative state. Recalling that the bare ground state always exists and is stable, regions whose aridity classes imply only the existence of this stable state or its coexistence with the occurrence of upper threshold vegetative patterns are vulnerable to desertification which can then be reversed by the land management strategies of crust disturbance for soil, seed augmentation for plants, and irrigation for surface water. Meron et al. [29] provided a positive-feedback cycling mechanism to explain the formation of bare patches characteristic of vegetative patterning along such a precipitation gradient. Note that a process of this sort occurs in all directions for bare gaps or pseudo gaps but only in two directions for bare interstripes.

In summary, after reprising the one-dimensional and hexagonal planform results of Kealy and Wollkind [2] for their interaction-diffusion plant-surface water model system in an arid flat environment, we extended that analysis by performing a rhombic planform analysis as well. We found that, although square vegetative patterns could not occur for our system, rhombic arrays of other characteristic angles included in two bands flanking

Our main result could be represented by closed form plots in the rainfall a versus plant loss

Finally, we introduced an aridity classification scheme, with classes based upon the inherent vegetative patterns included in that predicted morphological sequence along a rainfall gradient, which could be used both to forecast the possibility of desertification and to propose land management strategies to reverse this process. Implicit to our continuum formulation were the assumptions that the pattern wavelength was much greater than the mean coverage diameter of an individual plant but much less than the length scale characteristic of the arid environment which allowed us to have considered our interaction-diffusion equations on an unbounded spatial domain [30] .

We conclude by noting that although these results of our weakly nonlinear stability analyses are only asymptotically valid in the neighborhood of the marginal stability curve and the Go-Gub acacia tiger bush example as well as the occurrence of the rhombic vegetative arrays were restricted to such a region, numerical simulations of pattern formation for several reaction-diffusion systems or model evolution equations have shown that theoretical predictions of this sort can often be extended to those regions of the relevant parameter space relatively far from the marginal curve [8] [31] .

References

- Couteron, P., Mahamane, A., Ouedraogo, P. and Seghieri, J. (2000) Differences between Banded Thickets (Tiger Bush) in Two Sites in West Africa. Journal of Vegetation Sciences, 11, 321-328. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3236624

- Kealy, B.J. and Wollkind, D.J. (2012) A Nonlinear Stability Analysis of Vegetative Turing Pattern Formation for an Interaction-Diffusion Plant-Surface Water Model System in an Arid Flat Environment. Bulletin of Mathematical Biology, 74, 803-833. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11538-011-9688-7

- Klausmeier, C.A. (1999) Regular and Irregular Patterns in Semiarid Vegetation. Science, 284, 1826-1828. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.284.5421.1826

- Turing, A.M. (1952) The Chemical Basis of Morphogenesis. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 237, 37-72. http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rstb.1952.0012

- Rietkerk, M., Boerlijst, M.C., van Langevelde, F., HilleRisLambers, R., van de Koppel, J., Kumar, L., Prins, H.H.T. and de Roos, A.M. (2002) Self-Organization of Vegetation in Arid Ecosystems. The American Naturalist, 160, 524- 530. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/342078

- Lefever, R. and Lejeune, O. (1997) On the Origin of Tiger Bush. Bulletin of Mathematical Biology, 59, 263-294. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02462004

- Wollkind, D.J. and Stephenson, L.E. (2000) Chemical Turing Pattern Formation Analyses: Comparison of Theory with Experiment. SIAM Journal of Applied Mathematics, 61, 387-431. http://dx.doi.org/10.1137/S0036139997326211

- Boonkorkuea, N., Lenbury, Y., Alvarado, F.J. and Wollkind, D.J. (2010) Nonlinear Stability Analyses of Vegetative Pattern Formation in an Arid Environment. Journal of Biological Dynamics, 4, 346-380. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17513750903301954

- Cangelosi, R.A., Wollkind, D.J., Kealy-Dichone, B.J. and Chaiya, I. (2014) Nonlinear Turing Patterns for a Mussel-Algae Model. Journal of Mathematical Biology, 70, 1249-1294. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00285-014-0794-7

- Lejeune, O., Tildi, M. and Lefever, R. (2004) Vegetation Spots and Stripes in Arid Landscapes. International Journal of Quantum Chemistry, 98, 261-271. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/qua.10878

- Wollkind, D.J. (2001) Rhombic and Hexagonal Weakly Nonlinear Stability Analyses: Theory and Applications. In: Debnath, L., Ed., Nonlinear Stability Analysis, Vol. II, WIT Press, Southampton, 221-272.

- Wollkind, D.J., Manoranjan, V.S. and Zhang, L. (1994) Weakly Nonlinear Stability Analyses of Reaction-Diffusion Model Equations. Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics, 36, 176-214. http://dx.doi.org/10.1137/1036052

- Geddes, J.B., Indik, R.A., Moloney, J.V. and Firth, W.J. (1994) Hexagons and Squares in a Passive Nonlinear Optical System. Physical Review A, 50, 3471-3485. http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.50.3471

- Cross, M.C. and Hohenberg, P.C. (1993) Pattern Formation outside of Equilibrium. Reviews of Modern Physics, 65, 851-1112. http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.65.851

- Sekimura, T., Zhu, M., Cook, J., Maini, P.K. and Murray, J.D. (1999) Pattern Formation of Scale Cells in Lepidoptera by Differential Origin-Dependent Cell Adhesion. Bulletin of Mathematical Biology, 61, 807-827. http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/bulm.1998.0062

- Golovin, A.A., Nepomnyashchy, A.A. and Pismen, L.M. (1995) Pattern Formation in Large-Scale Marangoni Convection with Deformable Interface. Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena, 81, 117-147. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0167-2789(94)00184-R

- Schatz, M.F., VanHook, S.J., McCormick, W.D., Swift, J.B. and Swinney, H.L. (1999) Time-Independent Square Patterns in Surface-Tension-Driven Bénard Convection. Physics of Fluids, 11, 2577-2582. http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.870120

- von Hardenberg, J., Meron, E., Shachak, M. and Zarmi, Y. (2001) Diversity of Vegetation Patterns and Desertification. Physical Review Letters, 87, Article ID: 198101. http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.87.198101

- Rietkerk, M., Dekker, S.C., de Ruiter, P.C. and van de Koppel, J. (2004) Self-Organized Patchiness and Catastrophic Shift in Ecosystems. Science, 305, 1926-1929. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1101867

- Sherratt, J.A. (2005) An Analysis of Vegetative Stripe Formation in Semi-Arid Landscapes. Journal of Mathematical Biology, 51, 183-197. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00285-005-0319-5

- Sherratt, J.A. and Lord, G.J. (2007) Nonlinear Dynamics and Pattern Bifurcations in a Model for Vegetation Stripes in Semi-Arid Environments. Theoretical Population Biology, 71, 1-11. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tpb.2006.07.009

- Deblauwe, V., Couteron, P., Lejeune, O., Bogaert, J. and Barbier, N. (2011) Environmental Modulation of Self-Orga- nized Periodic Vegetative Patterns in Sudan. Ecography, 34, 990-1001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0587.2010.06694.x

- van der Stelt, S., Doelman, A., Hek, G. and Rademacher, J.D.M. (2013) Rise and Fall of Periodic Patterns for a Generalized Klausmeier-Gray-Scott Model. Journal of Nonlinear Science, 23, 39-95. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00332-012-9139-0

- Ursino, N. (2005) The Influence of Soil Properties on the Formation of Unstable Vegetation Patterns on Hillsides of Semiarid Catchments. Advanced Water Resources, 28, 956-963. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.advwatres.2005.02.009

- Morgan, D.S., Doelman, A. and Kaper, T.J. (2000) Stationary Periodic Patterns in the 1D Gray-Scott Model. Methods of Applied Analysis, 7, 105-115.

- Pearson, J.E. (1993) Complex Patterns in a Simple System. Science, 261, 189-192. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.261.5118.189

- Segel, L.A. (1965) The Nonlinear Interaction of a Finite Number of Disturbances to a Fluid Layer Heated from Below. Journal of Fluid Mechanics, 21, 359-384. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S002211206500023X

- Chen, W. and Ward, M.J. (2011) The Stability and Dynamics of Localized Spot Patterns in the Two-Dimensional Gray-Scott Model. SIAM Journal of Dynamical Systems, 10, 586-666. http://dx.doi.org/10.1137/09077357x

- Meron, E., Gilad, E., von Hardenberg, J., Shachuk, M. and Zarmi, Y. (2004) Vegetation Patterns along a Rainfall Gradient. Chaos, Solitons, and Fractals, 19, 367-376. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0960-0779(03)00049-3

- Golovin, A.A., Matkowsky, B.J. and Volpert, V.A. (2008) Turing Pattern Formation in the Brusselator Model with Superdiffusion. SIAM Journal of Applied Mathematics, 69, 251-272. http://dx.doi.org/10.1137/070703454

- Graham, M.D., Kevrekidis, J.G., Asakura, K., Lauterbach, J., Krishner, K., Rotermund, H.-H. and Ertl, G. (1994) Effects of Boundaries on Pattern Formation: Catalytic Oxidation of CO on Platinum. Science, 264, 80-82. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.264.5155.80

Appendix

Defining the vectors

and the

we catalogue the explicit formulae for the Landau constants appearing in Kealy and Wollkind [2] :

where

with

for

and

where

with

and

Observe, as Wollkind and Stephenson [7] have pointed out, that the expression for

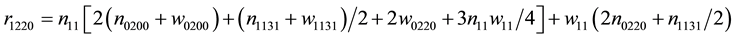

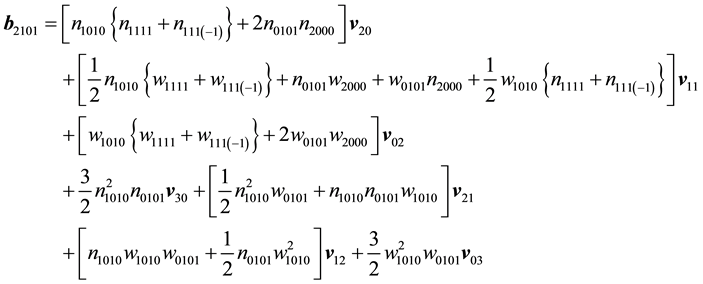

Finally, we catalogue the components relevant to the second rhombic-planform third-order Landau constant of (3.9)-(3.10):

where

for