International Journal of Clinical Medicine

Vol. 3 No. 7 (2012) , Article ID: 26205 , 6 pages DOI:10.4236/ijcm.2012.37117

Airway Foreign Body in Children

![]()

1Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Tan Tock Seng Hospital, Singapore City, Singapore; 2Department of Otolaryngology, KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital Singapore City, Singapore.

Email: Henry.Tan.KK@kkh.com.sg

Received September 13th, 2012; revised October 18th, 2012; accepted November 16th, 2012

Keywords: Airway; Foreign Body; Children

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Foreign body aspiration is not uncommon in children. It can be associated with significant morbidity and mortality. This study aims to determine and analyze the characteristics of local pediatrics airway foreign body (FB) aspiration. Methods: A retrospective study of medical records from KK hospital (1997-2010) is done. Patient demographics, clinical/investigative findings, duration of hospitalization and complications are analyzed. Results: The sample consisted of 26 patients (eight months - 13 years of age), who underwent rigid bronchoscopy for FB removal over the last 13 years. Seventy-seven percent were three years of age or younger. Peak incidence (61.6%) was at one to two years of age. Nineteen were males and seven were females. The top three clinical presentations were: cough (61.5%), choking (46.2%) and wheezing (42.3%). Decreased air entry (34.6%), tachypnea (26.9%) and no significant findings (23.1%) were the most common features on physical examination. The most common radiographic findings were consolidation (30.8%), presence of a foreign body (23.1%) and no abnormality (23.1%). Aspiration was primarily into the right main bronchus (38.5%), and 61.5% of the FB was organic in nature [principally peanuts (38.5%)]. Mean hospitalization duration was three days. Delayed diagnose in three cases were secondary to mis-diagnoses as croup (n = two) and respiratory tract infection (n = one). Complications were noted in eight cases (30.8%). There was no mortality. Conclusion: High index of suspicion is required in diagnosing airway FB. Physician’s diagnostic acumen is vital in prompt successful treatment. Heightening public’s awareness is the key to prevention of pediatrics FB aspiration.

1. Introduction

Foreign body aspiration in children is a significant cause of childhood morbidity and mortality worldwide. According to National Safety Council statistics for United States in year 2002, more than 4100 episodes of fatal aspiration were reported. Early diagnosis of foreign body aspiration is essential as delay in its recognition and treatment is related to significant complications [1]. Nevertheless, clinical presentation of aspiration can be subtle, mimicking other respiratory conditions, resulting in mis-management [2,3]. The role of imaging, rigid and flexible bronchoscopy in the management of foreign body aspiration is also a subject of much discussion and controversy [4-6]. This study serves as the first local study to investigate the characteristics of pediatrics foreign body aspiration; and the role of the various investigative and diagnostic modalities. Some comparisons with the results observed from other pediatric populations reported by other journals, predominantly from the Western countries were done.

2. Methods

A retrospective study of medical records from KK hospital (1997-2010) was performed. Variables studied include:

1) Patient’s demographics: age, gender and ethnicity;

2) Clinical presentation which includes history and findings on physical examination;

3) Interval between symptom onset to diagnosis;

4) Causes for delayed diagnosis and prior diagnosis, if any;

5) Investigative findings: Chest radiograph and bronchoscopic findings;

6) Foreign body implicated;

7) Location of the foreign body;

8) Complications;

9) Duration of hospitalization;

3. Results

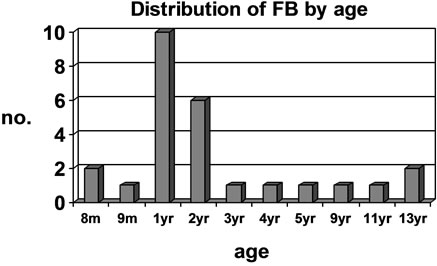

Review of the medical records showed a total of 26 patients, aged from eight months to 13 years, underwent rigid bronchoscopy for foreign body removal over the past 13 years. Seventy-seven percent were three years and below. Peak incidence (61.6%) was at one to two years of age (Figure 1). Nineteen were males and seven were females, leading to a male: female ratio of 2.7:1. There were ten (38.5%) Chinese, six (23.1%) Malays, six (23.1%) Indians and four (15.3%) were of other ethnicity.

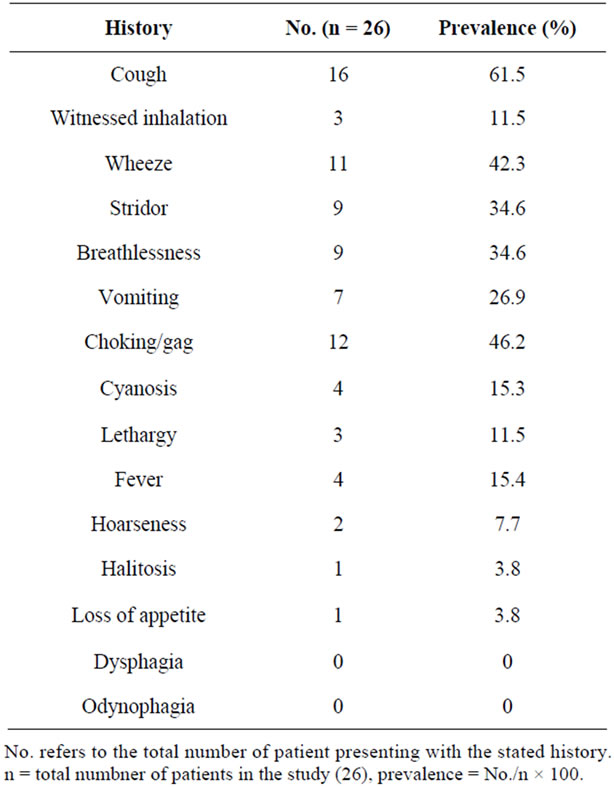

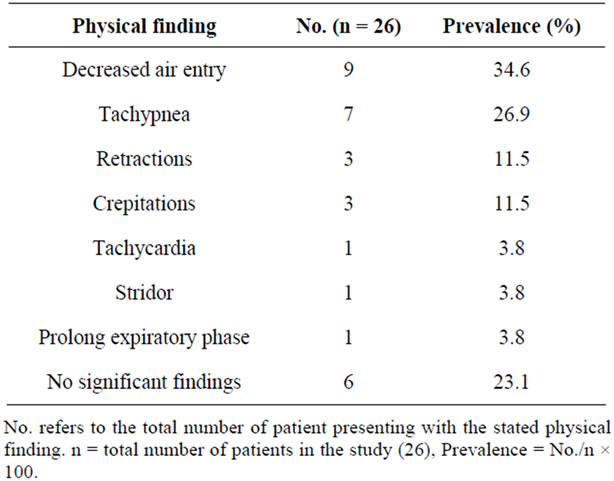

The top five clinical presentations were: cough (61.5%), choking (46.2%), wheeze (42.3%), stridor (34.6%) and breathlessness (34.6%) (Table 1). Some patients presented with combination of these symptoms. Prolonged cough defined as more than one week duration was noted in 26.7% of those presenting with cough. Decreased air entry (34.6%) and tachypnea (26.9%) are the most common physical findings, followed by no significant findings (23.1%) (Table 2). Clinical triad of decreased air entry, wheeze and cough was only noted in four cases (15.4%).

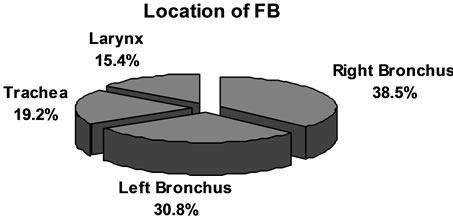

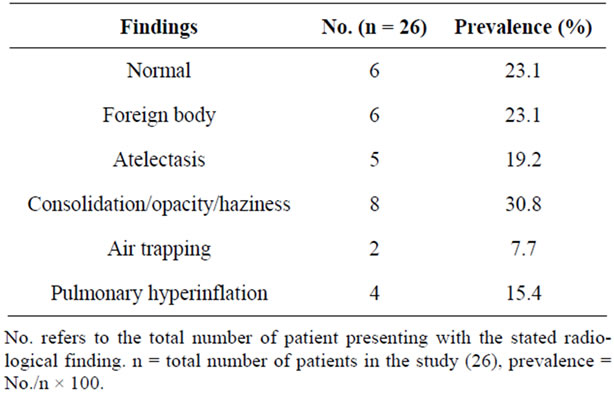

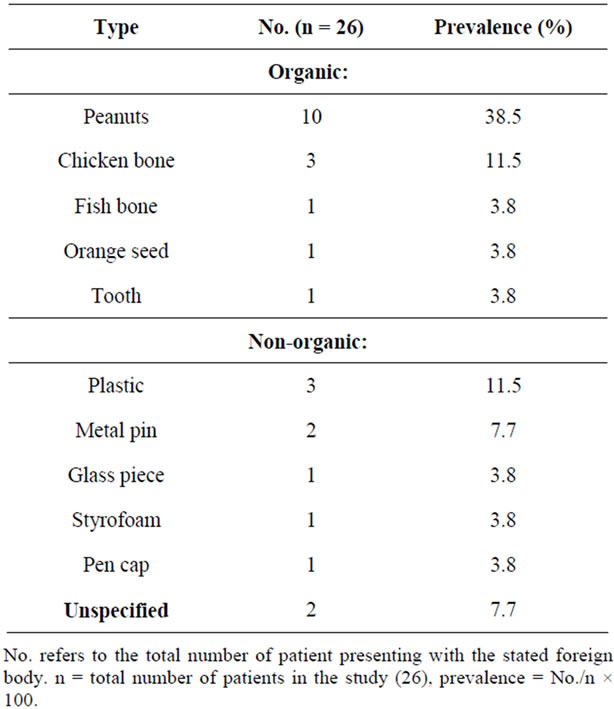

Consolidation (30.8%) and atelectasis (19.2%) were the most common radiographic findings. A normal radiograph was noted in 23.1% of radiographs (Table 3). Foreign body was only seen in 23.1% of radiographs. Aspiration was primarily into right main bronchus (38.5%), 30.8% were into the left bronchus (Figure 2). Sixty two percent of the foreign bodies implicated were organic in nature [principally peanuts (38.5%)]; while plastic was

Table 1. Distribution by history.

Figure 1. Chart showing distribution of FB by age. Y axis = No. of patient at the particular age. X axis = age of patient in months (m) and years (yr).

Figure 2. Chart showing distribution (%) of FB by location.

Table 2. Distribution by physical findings.

the most common non-organic object detected (11.5%) (Table 4).

Duration of hospitalization ranges from one to 17 days, with a mean of three days. Delayed diagnosis and treatment (24 hours and beyond) were noted in three cases and secondary to mis-diagnoses as croup (n = 2) and respiratory tract infection (n = 1). Otherwise, the remaining 23 patients (88.5%) were admitted within 24 hours from symptom onset. Repeat bronchoscopy was done for a case of incomplete removal of foreign body back in Bangladesh.

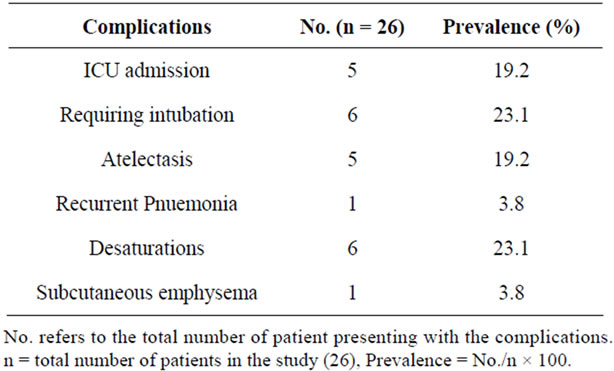

Complications defined as preoperative or secondary to bronchoscopy were noted in 8 cases (30.8%). This include: desaturations (23.1%), requiring intubation (23.1%), ICU admission (19.2%), atelectasis (19.2%) and others (Table 5).

Table 3. Distribution by radiological findings.

Table 4. Distribution by type of foreign body.

No mortality was present in our series. Post operatively, all patients were covered with antibiotics and steroids, and were well on follow up.

4. Discussion

Our study showed that majority of foreign body aspiration occurred below three years of age (76.9%) which is consistent with the findings from other studies [7-13]. This can be attributed to the tendency of children at this age to explore their world via the oral routes, the fact that they might not have developed the full posterior dentition and their immature neuromuscular mechanism for swallowing and airway protection.

The male to female ratio of 2.7:1 as reported from our

Table 5. Distribution by complications.

series is similar with that reported by other studies. [8,9,12] The reason for male predominance remains unclear, however, some attributed it to the more adventurous and impulsive nature of young boys [14].

A history of choking is reported to have a high clinical sensitivity (97%) as well as clinical specificity (63%) in the diagnosis of foreign body aspiration. [15] It is also a major clinical finding, being present in more than 80% of cases in two series [16,17]. Unfortunately, the initial choking episode may be downplayed or missed by parents; only to be recollected upon removal of the foreign body. Locally, choking is documented as a presenting complaint in only 46.2% of the cases and is superseded by cough (61.5%). The classic triad of wheeze, cough, and diminished breath sounds , despite its high specificity of 96% - 98% as reported in a Switzerland based study [18], is not universally present [6,17]. It is present in only four cases in our series (15.4%).

Decreased air entry (34.6%) accounts for the predominant physical finding in our study, followed by tachypnea (26.9%). This finding has high specificity [3] but is however subjective and does not give much clue to the position of the foreign body [19]. In our study, 23.1% presented with normal physical findings. Hence, the absence of abnormality on physical examination does not exclude the presence of foreign body.

Normal chest radiograph is noted in six cases (23.1%); this is similar to that reported in a Danish study [20]. The other significant findings include consolidation/opacity (30.8%) and atelectasis (19.2%). Foreign body is only detected in 23.1% of the radiographs. This low sensitivity could be secondary to the fact that many foreign objects consumed by children are radiolucent in nature. Hence, the presence of a normal chest radiograph should not rule out the possibility of foreign body aspiration [20-22], though a positive finding may be highly suggestive of its presence.

Other modality of imaging such as fluoroscopy has also been advocated as initial diagnostic technique of choice [6,23]. Hong et al. [23] have also recommended the use of spiral and sine CT in cases of diagnostic dilemmas. These are however not used locally and further studies may be warranted to further evaluate the costbenefit ratio of introducing these high-end diagnostic adjuncts.

Sixty two percent of the foreign body implicated is organic in nature, of which, peanuts predominates (38.5%). Peanut is similarly the chief culprit in other studies [7,8,10,24,25]. The foreign body implicated is to a certain extent dependent on the education, culture and dietary habits of the country. Hence, parents should be educated on food safety and keeping food such as peanut out of reach from their young children.

Anatomically, the right bronchus, due to its greater diameter, smaller angle of divergence from the tracheal axis and greater airflow, favours the entry of foreign body. The incidence of foreign body in the right bronchus in our series is 38.5% compared to 30.8% in the left bronchus. The remaining are into the tracheal (19.2%) and larynx (15.4%). Higher incidence in right bronchus is similarly reported in most studies [5,9,10,12,13,25-29].

Delayed diagnosis and treatment (24h and beyond) was noted in three cases (11.5%). Two cases occurred in a one-year old girl and a two-year old boy. They were both given the prior diagnosis of croup and were treated with steroids for duration of two days and two months respectively. Bronchoscopy was eventually done in view of worsening condition despite medical therapy. Plastic piece and chicken bone were found and removed. The two children were hospitalized for six and nine days respectively. Complications encountered included desaturations, ICU admission and requiring intubation. The 3rd case of delayed diagnosis occurred in a nine-year old girl and involved aspiration of a tooth into the left bronchus. She presented with prolonged cough and was treated symptomatically by a private physician. The foreign body was only discovered two months later, when the chests radiograph done at the polyclinic revealed foreign body in the left main bronchus, associated with shifted mediastinum, left lung collapse and consolidation. She underwent rigid bronchoscopy for foreign body extraction, from which a tooth was found lodged at the junction between the left main and segmental bronchus. The patient and her caregiver subsequently recalled a history of fallen tooth which was swallowed two months prior. This case with delayed diagnosis was also associated with prolonged hospitalization of ten days, of which four days was spent in ICU. Other complications include: post operative desaturations, requiring intubation and positive pressure ventilation, subcutaneous emphysema, pnuemomediastinum and persistent pneumonia and collapse of the left lung.

Other papers have also quoted misinterpretation of symptoms as a leading cause of delayed diagnosis, of which common prior diagnosis include: asthma, asthma exacerbation, croup and pneumonia [6,30,31]. Esclamado RM [1] reported complication associated with delayed diagnosis to be 67%. Conversely, complication free course was described in all patients presenting within 24 hours from aspiration by a study based in Turkey [32,33]. Hence, foreign body aspiration may present with subtle unspecific symptoms or mimic other respiratory conditions. A high index of suspicion of foreign body aspiration is crucial in ensuring prompt treatment which will aid in decreasing complications and prolonged hospitalization associated with delayed diagnosis.

Rigid bronchoscopy is the standard of care in the management of cases of suspected foreign body aspiration. It is the procedure of choice to identify and remove the object [33-35] due to its better control of the airway, allowing good visualization and manipulation [4,36,37]. In our institution, all cases of foreign body aspiration was extracted with rigid bronchoscopy. Flexible bronchoscopy is also advocated by some author and complication rate reported to be as low as 0.3% versus 1.1% from rigid bronchoscopy [4]. Further studies are required to determine the diagnostic and therapeutic efficacy, the cost, physician’s preference and indication for rigid/flexible bronchoscopy.

The overall complication rate in our study is 30.8%. There was no mortality, as has been described by other authors [38-40]. Bronchoscopy was done in all patients within 24 hours from admission. Majority (84.6%) was discharged within three days from admission, showing the safety and favourable outcome of bronchoscopy [24,36,41].

Notably, the incidence of foreign body aspiration in our population (26 cases over 13 year period) is relatively low compared to other population. We postulate that this observation could be secondary to the smaller peadiatrics population size, higher education level of the parents and children, culture of tight parental/caregiver supervision of children, their practice of keeping hazardous parts/food from children and possibly the more docile and less adventurous nature of local children. Nation wide prevention programs which include educational programs and materials have reported varying success in lowering the incidence of foreign body aspiration [42,43].

5. Conclusion

There are no single or combined variables that can predict airway foreign body with full certainty. A high index of suspicion is required in its diagnosis. Diagnostic acumen and prompt treatment aids in decreasing complications, morbidity and mortality. Rigid bronchoscopy remains the standard of care and should be done at the earliest instance in cases of suspected foreign body aspiration. Heightening awareness of general public through education is the key to prevention and prompt treatment.

REFERENCES

- R. M. Esclamado and M. A. Richardson, “Laryngotracheal Foreign Bodies in Children. A Comparison with Bronchial Foreign Bodies,” American Journal of Diseases of Children, Vol. 141, No. 3, 1987, pp. 259-262.

- T. Hilliard, R. Sim, M. Saunders, S. L. Hewer and J. Henderson, “Delayed Diagnosis of Foreign Body Aspiration in Children,” Emergency Medicine Journal, Vol. 20, No. 1, 2003, pp. 100-101. doi:10.1136/emj.20.1.100

- F. Karakoc, E. Cakir, R. Ersu, Z. S. Uyan, B. Colak, B. Karadag, G. Kiyan, T. Dagli and E. Dagli, “Late Diagnosis of Foreign Body Aspiration in Children with Chronic Respiratory Symptoms,” International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, Vol. 71, No. 2, 2007, pp. 241-246. doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2006.10.006

- S. Cohen, H. Pine and A. Drake, “Use of Rigid and Flexible Bronchoscopy among Pediatric Otolaryngologists,” Archives of Otolaryngology—Head & Neck Surgery, Vol. 127, No. 5, 2001, pp. 505-509.

- C. E. Skoulakis, P. G. Doxas, C. E. Papadakis, E. Proimos, P. Christodoulou, J. G. Bizakis, G. A. Velegrakis, D. Mamoulakis and E. S. Helidonis, “Bronchoscopy for Foreign Body Removal in Children. A Review and Analysis of 210 Cases,” International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, Vol. 53, No. 2, 2000, pp. 143-148. doi:10.1016/S0165-5876(00)00324-4

- H. K. Tan, K.Brown, T. McGill, M. A. Kenna, D. P. Lund and G. B. Healy, “Airway Foreign Bodies (FB): A 10-Year Review,” International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, Vol. 56, No. 2, 2000, pp. 91-99. doi:10.1016/S0165-5876(00)00391-8

- R. Altkorn, X. Chen, S. Milkovich, D. Stool, G. Rider, C. M. Bailey, A. Haas, K. H. Riding, S. M. Pransky and J. S. Reilly, “Fatal and Non-Fatal Food Injuries among Children (Aged 0 - 14 Years),” International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, Vol. 72, No. 7, 2008, pp. 1041-1046. doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2008.03.010

- P. F. Bittencourt, P. A. Camargos, P. Scheinmann and J. de Blic, “Foreign Body Aspiration: Clinical, Radiological Findings and Factors Associated with Its Late Removal,” International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, Vol. 70, No. 5, 2006, pp. 879-884. doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2005.09.024

- J. Roda, S. Nobre, J. Pires, M. H. Estevao and M. Felix, “Foreign Bodies in the Airway: A Quarter of A Century’s Experience,” Revista Portuguesa de Pneumologia, Vol. 14, No. 6, 2008, pp. 787-802.

- X. Latifi, A. Mustafa and Q. Hysenaj, “Rigid Tracheobronchoscopy in the Management of Airway Foreign Bodies: 10 Years Experience in Kosovo,” International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, Vol. 70, No. 12, 2006, pp. 2055-2059. doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2006.07.017

- F. Oguz, A. Citak, E. Unuvar and M. Sidal, “Airway Foreign Bodies in Childhood,” International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, Vol. 52, No. 1, 2000, pp. 11-16. doi:10.1016/S0165-5876(99)00283-9

- K. Mantel and I. Butenandt, “Tracheobronchial Foreign Body Aspiration in Childhood,” European Journal of Pediatrics, Vol. 145, No. 3, 1986, pp. 211-216. doi:10.1007/BF00446068

- A. M. Shivakumar, A. S. Naik, K. B. Prashanth, K. D. Shetty and D. S. Praveen, “Tracheobronchial Foreign Bodies,” The Indian Journal of Pediatrics, Vol. 70, No. 10, 2003, pp. 793-797. doi:10.1007/BF02723797

- C. Y. Chiu, K. S. Wong, S. H. Lai, S. H. Hsia and C. T. Wu, “Factors Predicting Early Diagnosis of Foreign Body Aspiration in Children,” Pediatric Emergency Care, Vol. 21, No. 3, 2005, pp. 161-164.

- J. E. B.Fontoba, C. Gutierrez, J. Lluna, J. J. Vila, J. Poquet and S. Ruiz-Company, “Bronchial Foreign Body: Should Bronchoscopy Be Performed in All Patients with A Choking Crisis?” Pediatric Surgery International, Vol. 12, No. 2-3, 1997, pp. 118-120. doi:10.1007/BF01349976

- R. E. Morley, J. P. Ludemann, J. P. Moxham, F. K. Kozak and K. H. Riding, “Foreign Body Aspiration in Infants and Toddlers: Recent Trends in British Columbia,” The Journal of Otolaryngology, Vol. 33, No. 1, 2004, 2004, pp. 37-41. doi:10.2310/7070.2004.00310

- N. E. Wiseman, “The Diagnosis of Foreign Body Aspiration in Childhood,” Journal of Pediatric Surgery, Vol. 19, No. 5, 1984, pp. 531-535. doi:10.1016/S0022-3468(84)80097-4

- M. Tomaske, A. C. Gerber, S. Stocker and M. Weiss, “Tracheobronchial Foreign Body Aspiration in ChildrenDiagnostic Value of Symptoms and Signs,” Swiss Medical Weekly, Vol. 136, No. 33-34, 2006, pp. 533-538.

- H. David and D. H. Darrow, “Pediatric Otolaryngology. Chapter 90: Foreign Bodies of the Larynx, Trachea, and Bronchi,” 4th Edition, Saunders (Elsevier Science), Philadelphia, 2003.

- B. C. Becker and T. G. Nielsen, “Foreign Bodies in the Airways and Esophagus in Children,” Ugeskrift for Læger, Vol. 156, No. 30, 1994, pp. 4336-4339.

- J. T. Zerella, M. Dimler, L. C. McGill and K. J. Pippus, “Foreign Body Aspiration in Children: Value of Radiography and Complications of Bronchoscopy,” Journal of Pediatric Surgery, Vol. 33, No. 11, 1998, pp. 1651-1654. doi:10.1016/S0022-3468(98)90601-7

- A. B. Silva, H. R. Muntz and R. Clary, “Utility of Conventional Radiography in the Diagnosis and Management of Pediatric Airway Foreign Bodies,” Annals of Otology, Rhinology and Laryngology, Vol. 107, No. 10, 1998, pp. 834-838.

- S. J. Hong, H. W. Goo and J. L. Roh, “Utility of Spiral and Cine CT Scans in Pediatric Patients Suspected of Aspirating Radiolucent Foreign Bodies,” Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery, Vol. 138, No. 5, 2008, pp. 576-580. doi:10.1016/j.otohns.2007.12.039

- F. L. Tang, M. Z. Chen, Z. L. Du, C. C. Zou and Y. Z. Zhao, “Fibrobronchoscopic Treatment of Foreign Body Aspiration in Children: An Experience of 5 Years in Hangzhou City, China,” Journal of Pediatric Surgery, Vol. 41, No. 1, 2006, pp. e1-e5. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.10.064

- S. P. Yadav, J. Singh, N. Aggarwal and A. Goel, “Airway Foreign Bodies in Children: Experience of 132 Cases,” Singapore Medical Journal, Vol. 48, No. 9, 2007, pp. 850-853.

- J. C. Fraga, A. F. Pires, M. Komlos, E. E. Takamatu, L. G. Camargo and F. H. Contelli, “Bronchoscopic Removal of Foreign Body from Airway through Tracheotomy or Tracheostomy,” Jornal de Pediatria, Vol. 79, No. 2003, pp. 369-372. doi:10.1590/S0021-75572003000400017

- V. Erikci, S. Karacay and A. Arikan, “Foreign Body Aspiration: A Four-Years Experience,” Ulusal Travma ve Acil Cerrahi Dergisi, Vol. 9, No. 1, 2003, pp. 45-49.

- A. Pinto, M. Scaglione, F. Pinto, G. Guidi, M. Pepe, B. Del Prato, R. Grassi and L. Romano, “Tracheobronchial Aspiration of Foreign Bodies: Current Indications for Emergency Plain Chest Radiography,” La Radiologia Medica, Vol. 111, No. 4, 2006, pp. 497-506. doi:10.1007/s11547-006-0045-0

- F. Brkic and S. Umihanic, “Tracheobronchial Foreign Bodies in Children. Experience at ORL Clinic Tuzla, 1954-2004,” International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngolog, Vol. 71. No. 6, 2007, pp. 909-915.

- L. Mu, P. He and D. Sun, “Inhalation of Foreign Bodies in Chinese Children: A Review of 400 Cases,” Laryngoscope, Vol. 101, No. 6, 1991, pp. 657-660. doi:10.1288/00005537-199106000-00014

- A. Kugelman, R. Shaoul, M. Goldsher and I. Srugo, “Persistent Cough and Failure to Thrive: A Presentation of Foreign Body Aspiration in a Child with Asthma,” Pediatrics, Vol. 117, No. 5, 2006, pp. e1057-e1060. doi:10.1542/peds.2005-2196

- M. Sirmali, H. Turut, E. Kisacik, G. Findik, S. Kaya and I. Tastepe, “The Relationship between Time of Admittance and Complications in Paediatric Tracheobronchial Foreign Body Aspiration,” Acta Chirurgica Belgica, Vol. 105, No. 6, 2005, pp. 631-634.

- A. Martinot, M. Closset, C. H. Marquette, V. Hue, A. Deschildre, P. Ramon, J. Remy and F. Leclerc, “Indications for Flexible versus Rigid Bronchoscopy in Children with Suspected Foreign-Body Aspiration,” American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, Vol. 155, No. 5, 1997, pp. 1676-1679.

- P. C. Fitzpatrick and J. L. Guarisco, “Pediatric Airway Foreign Bodies,” The Journal of the Louisiana State Medical Society, Vol. 150, No. 4, 1998, pp. 138-141.

- Z. J. Chen, F. G. Zhu, N. K. Zhang, and J. J. Chen, “Therapeutic Experience from 1428 Patients with Pediatric Tracheobronchial Foreign Body,” Journal of Pediatric Surgery, Vol. 43, No. 4, 2008, pp. 718-721. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2007.10.010

- M. Asif, S. A. Shah, F. Khan and R. Ghani, “Foreign Body Inhalation-Site of Impaction and Efficacy of Rigid Bronchoscopy,” Journal of Ayub Medical College Abbottabad, Vol. 19, No. 2, 2007, pp. 46-48.

- J. A. Nakhosteen, “Tracheobronchial Foreign Bodies,” European Respiratory Journal, Vol. 7, No. 3, 1994, pp. 429-430. doi:10.1183/09031936.94.07030429

- M. Fraga Ade, M. C. Reis, M. P. Zambon, I. C. Toro, J. D. Ribeiro and E. C. Baracat, “Foreign Body Aspiration in Children: Clinical Aspects, Radiological Aspects and Bronchoscopic Treatment,” The Jornal Brasileiro de Pneumologia, Vol. 34, No. 2, 2008, pp. 74-82.

- R. E. Black, D. G. Johnson and M. E. Matlak, “Bronchoscopic Removal of Aspirated Foreign Bodies in Children,” Journal of Pediatric Surgery, Vol. 29, No. 5, 1994, pp. 682-684. doi:10.1016/0022-3468(94)90740-4

- G. M. Zaytoun, P. W. Rouadi and D. H. Baki, “Endoscopic Management of Foreign Bodies in the Tracheobronchial Tree: Predictive Factors for Complications,” Otolaryngology— Head and Neck Surgery, Vol. 123, No. 3, 2000, pp. 311-316. doi:10.1067/mhn.2000.105060

- D. W. Vane, J. Pritchard, C. W. Colville, K. W. West, H. Eigen and J. L. Grosfeld, “Bronchoscopy for Aspirated Foreign Bodies in Children. Experience in 131 Cases,” Archives of Surgery, Vol. 123, No. 7, 1988, pp. 885-888. doi:10.1001/archsurg.1988.01400310099017

- N. Despres, A. Lapointe, M. C. Quintal, P. Arcand, C. Giguere and A. Abela, “3-Year Impact of A Provincial Choking Prevention Program,” The Journal of Otolaryngy, Vol. 35, No. 4, 2006, pp. 216-221. doi:10.2310/7070.2005.0014

- N. Sadan, A. Raz and B. Wolach, “Impact of Community Educational Programmes on Foreign Body Aspiration in Israel,” European Journal of Pediatrics, Vol. 154, No. 10, 1995, pp. 859-862. doi:10.1007/BF01959798