Theoretical Economics Letters

Vol.04 No.09(2014), Article ID:52187,5 pages

10.4236/tel.2014.49108

Relationships, Human Behaviour and Financial Transactions

Mehdi Chowdhury

Business School, Bournemouth University, Bournemouth, UK

Email: mchowdhury@bournemouth.ac.uk

Copyright © 2014 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 17 October 2014; revised 26 November 2014; accepted 8 December 2014

ABSTRACT

It is widely known that relationships and human behaviours such as trust, reciprocity and altruism that are observed in the human societies are capable of facilitating financial transactions. This paper proposes a theoretical model to argue that though these elements can facilitate financial transactions, they may not always ensure efficiency in the sense of creation of additional wealth. As financial resources are scarce, the paper argues that the financial transactions induced by relationships, trust, reciprocity and altruism may lead to inefficient allocations of resources.

Keywords:

Efficiency, Human Behaviour, Financial Transactions

1. Introduction

The importance of relationships in financial intermediation is well recognised in the banking and finance literature. Financial intermediaries often confront the problem of information asymmetry and long established relationships between the lenders and borrowers can overcome this (Boot, 2000) [1] . Apart from relationships, recent works by experimental economists have well established that financial transactions can also be facilitated by human behaviours like altruism, trust and reciprocity (Fehr and Schmidt, 2006 [2] ). The importance of these behavioural elements has been also recognised by the economists who tried to explain the reasons for intra- family financial transfers. A survey of literature on intra-family financial transfers is available in Laferrère and Wolff (2006) [3] .

This paper asks if the financial transactions induced by relationships, trust, reciprocity and altruism can automatically ensure “Efficiency” in the sense of creation of additional wealth that market is otherwise unable to provide? It can be explained further by referring to an experiment conducted by Berg et al. (1995) [4] . In the experiment a subject “A” transfers a fraction from his initial endowment of $10 to an anonymous subject “B”. The amount transferred is multiplied by 3. B then transfers a fraction of that amount to A. Rationality or selfishness implies that subject A should not transfer any amount to B and B should not transfer any amount to A. This attitude however is not maximising their joint wealth, as, if A transfers no amount to B, then the total wealth is only $10 compared to the possible maximum of $30. Transactions are Pareto improving when A trusts B and transfers some money and B reciprocates by returning the money transferred by A.

In the actual economy resources are scarce and financial intermediaries are often credit constrained. Extending credit for one purpose implies a lack credit of for another purpose. Therefore relationships, trust, reciprocity and altruism can crowd-out rule based lendings. The transactions as addressed in Berg et al. (1995) [4] improve the joint welfare. There should be no objection if transactions based on relationships and behavioural elements always create additional wealth. The paper questions if it is the case all the time and argues that it is not. Actually some transactions can be wealth reducing, that is total wealth is higher if relationships or behavioural ele- ments fail to initiate transactions in the first place. This has been illustrated by a theoretical example of a simple principal-agent model, where the principal transfers money to the agent after receiving a guarantee from a third party. The basic message of the paper is very straight forward, that is relationships, trust, altruism and reciprocity based transactions can be inefficient. The paper serves to exemplify this message further.

It is possible to find a connection between this paper and the growing literature on individual and corporate social responsibility (Bénabou and Tirole, 2010 [5] ; Kitzmueller and Shimshack, 2012 [6] ). However, it is more linked to the growing support for relationship-based banking and networking. Though the paper can be viewed as a criticism of relationship-based banking, we are not undermining the importance of it in the actual economy. Its importance is already well established, such as past relationships reduced collateral requirements and also helped obtaining larger loans (Bharath et al., 2011 [7] ) and banking relationships contributed in reducing financial tension and credit rationing after the financial crisis of 2008 (Gobbi and Sette, 2013 [8] ; Bartolia et al., 2013 [9] ).

The structure of the remaining sections of the paper is as follows. The second section describes the model that forms the basis of argument. The third section analyses the conditions where transactions can be efficient or inefficient. The final section concludes the paper by providing a direction for future research.

2. The Model

The purpose of this section is to introduce the model which forms the basis of arguments in the later parts of the paper. We assume that there are three players in the model:

a. The Principal: who gives the loan, denoted as B(anker).

b. The Agent: who receives the loan, D(ebtor).

c. The Guarantor: who performs the role of a G(uarantor).

B gives loan amount l to D with an agreement that r will be repaid at the end of a pre-agreed period where r > l. If the amount is not repaid G is regarded as liable and hence the mechanism solves both adverse selection and moral hazard problems.

The assumptions of the model are,

a. G is altruistic. Altruism is defined as a mental condition as such G gets a psychological benefit from doing something good for D.

b. D reciprocates the behaviour of G. D aims to completely repay the loan so that G does not have to bear the burden of repayment of the loan.

c. B gives the loan on the basis of relationship or trust in G. The relationship and trust can be formed by mutual long term business/social interactions or by availability of collateral to support the loan repayment1. B is not altruistic to G or D. B only cares about loan repayment and does not attach any value to the sources of repayment.

The timeline of the acts are as follows: B lends l to D with a written or non-written contract which is enforceable under any contingencies. D invests in the project and exerts effort. The outcome is obtained and r amount is repaid to B irrespective of the outcome of the investment. The repayment may come from D or G or a combination of both. There is no uncertainly in repayment.

Relationships allow financial institutions to accumulate information about clients over a longer period of time and to develop trust and mutual understanding between banks and clients. As Boots (2000) [1] mentioned, relationship-based banking leads to the choice between rules and discretion where discretion allows decision making based on non-contractable information. There is therefore a trade-off in the use of relationships in financial lending from bank’s point of view. The paper is not concerned about this trade off as the bank always makes profit from the lending.

The investment

gives return

gives return

2 with probability

2 with probability

and 0 with probability

and 0 with probability . The probability of the return depends on the effort of D. Following the convention of notation, we denote effort level as

. The probability of the return depends on the effort of D. Following the convention of notation, we denote effort level as . The probability is given as

. The probability is given as

which is concave in effort as such

which is concave in effort as such

and

and . The effort is defined not in term of personal unobservable endeavour but rather as the personal investment of D in the project, which is expressible in monetary term. As

. The effort is defined not in term of personal unobservable endeavour but rather as the personal investment of D in the project, which is expressible in monetary term. As

is concave, the effort of D increases the probability of success of the project which implies that the project becomes more capable of attaining the objective. It is possible that

is concave, the effort of D increases the probability of success of the project which implies that the project becomes more capable of attaining the objective. It is possible that

goes up as

goes up as

goes up. We ignore that possibility to keep the exposition simple.

goes up. We ignore that possibility to keep the exposition simple.

Expected pay off of the project therefore is:

(1)

(1)

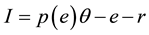

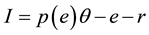

The income of D from the project minus repayment of loan is:

(2)

(2)

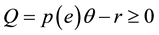

The project is viable if . To facilitate loan repayment from only the gross revenue of the project, the project needs to generate sufficient gross revenue so that following inequality is satisfied:

. To facilitate loan repayment from only the gross revenue of the project, the project needs to generate sufficient gross revenue so that following inequality is satisfied:

(3)

(3)

The gross revenue of the project needs to be mentioned specifically as when a project does not perform well, the gross revenue can provide information on repayment possibility. In difficult situations, struggling investors sometimes disregard their own monetary and non-monetary costs and look at gross revenues to repay loans. Equation (3) reflects that situation3.

Needless to say that,

gives the net revenue of the project.

gives the net revenue of the project.

3. Economic Efficiency of the Loan

This section analyses the effort level that D utilises to ensure repayment of the loan. It also analyses if the loan is economically viable, i.e. creates more wealth than what was initially available. It is analysed using following two cases:

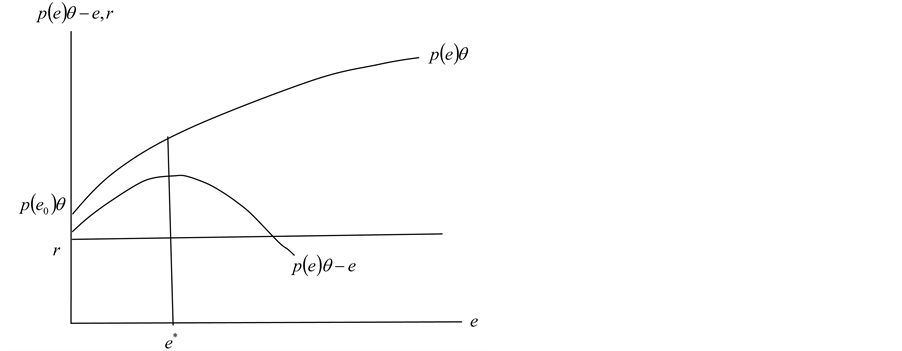

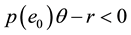

Case 1:

Here, with no effort, the expected income from the project is lower than the amount to be repaid. By assumption, the function

However, given the ex-ante situation that

The meaning of the effort

Case 2: If

Here the project is viable, as without any effort, D gets a non-negative return from the project. The situation is depicted in Figure 2. Given that

Figure 1. The project is not economically viable.

Figure 2. The project is economically viable.

the function

In case 2, the project is viable even without any effort of D. It is also possible that

We are now ready to analyse the efficiency of the transactions that is if the transactions create more wealth. Our benchmark here is the loan

The Principal (B):

The Agent (D):

The motive of the guarantor G is altruistic. We assume that it is non-expressible in monetary terms4. Therefore, in total, the monetary benefit of society from the transactions is

The findings of the case 1 crucially depends on the assumption that

4. Lessons and Conclusions

This paper provides a simple model to show that relationships, trust, reciprocity and altruism may provide solutions where regular market mechanisms fail but they do not automatically guarantee additional wealth. In the example of Figure 2, the project is capable of generating sufficient funds, but the example in Figure 1 shows the incapability of a project in generating sufficient funds for repayment of the loan.

We therefore can conclude that as resources are scarce, relationship, trust, reciprocity and altruism based financial intermediation may result in a suboptimal use of financial resources. The growing support for relationships, networking and emphasis of human behavioural elements are overlooking this possibility. The paper used a theoretical example, validity of which needs to be evaluated through empirical investigations. We therefore suggest for conducting empirical investigations on the subject matter, especially on financial intermediations in less developed countries where regulations and governance of financial institutions are known to be less transparent.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to express gratitude to Davide Secchi, Jens Hölscher, Sue Barnes and the seminar participants at Bournemouth University, UK. All the remaining errors are the author’s.

References

- Boot, A. (2000) Relationship Banking: What Do We Know? Journal of Financial Intermediation, 9, 7-25. http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/jfin.2000.0282

- Fehr, E. and Schmidt, K. (2006) The Economics of Fairness, Reciprocity and Altruism: Experimental Evidence and New Theories. In: Kolm, S.C. and Ythier, J.M., Eds., Handbook of Economics of Giving, Altruism and Reciprocity, 615-691.

- Laferrère, A. and Wolff, F.C. (2006) Microeconomic Models of Family Transfers. In: Kolm, S.C. and Ythier, J.M., Eds., Handbook of Economics of Giving, Altruism and Reciprocity, 889-969.

- Berg, J., Dickhaut, J. and McCabe, K. (1995) Trust, Reciprocity and Social History. Games and Economic Behavior, 10, 122-142. http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/game.1995.1027

- Bénabou, R. and Tirole, J. (2010) Individual and Corporate Social Responsibility. Economica, 77, 1-19. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0335.2009.00843.x

- Kitzmueller, M. and Shimshack, J. (2012) Economic Perspectives on Corporate Social Responsibility. Journal of Economic Literature, 50, 51-84. http://dx.doi.org/10.1257/jel.50.1.51

- Bharath, S., Dahiya, S., Saunders, A. and Srinivasan, A. (2011) Lending Relationships and Loan Contract Terms. Review of Financial Studies, 24, 1141-1203. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhp064

- Gobbi, G. and Sette, E. (2013) Do Firms Benefit from Concentrating Their Borrowing? Evidence from the Great Recession. Review of Finance, 18, 527-560. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/rof/rft017

- Bartolia, F., Ferrib, G., Murroc, P. and Rotondia, S. (2013) Bank-Firm Relations and the Role of Mutual Guarantee Institutions at the Peak of the Crisis. Journal of Financial Stability, 9, 90-104. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jfs.2012.03.003

NOTES

1Social norms can play an important role in enforcing contracts in the absence of formal enforcing mechanisms. Social norms may require G, under any contingencies, reciprocates the trust of B by ensuring the repayment of the loan.

2We assume

3This observation comes from the author’s personal experience of working in a bank.

4Note that the emphasis of the paper is to evaluate the monetary benefit of transactions, not the social welfare. This is applicable where any mechanism of transforming the intrinsic satisfaction of G to monetary values is absent.