Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

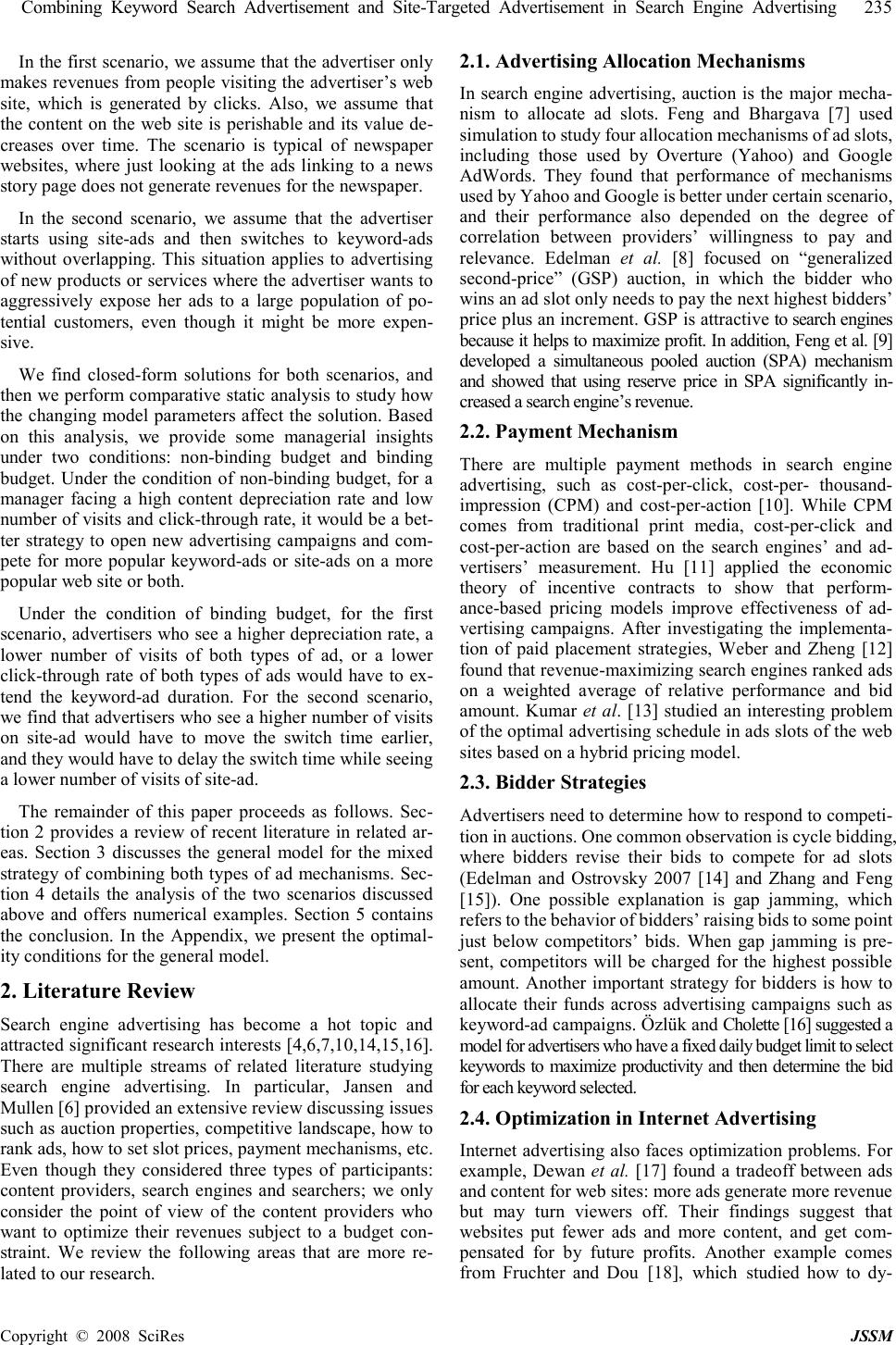

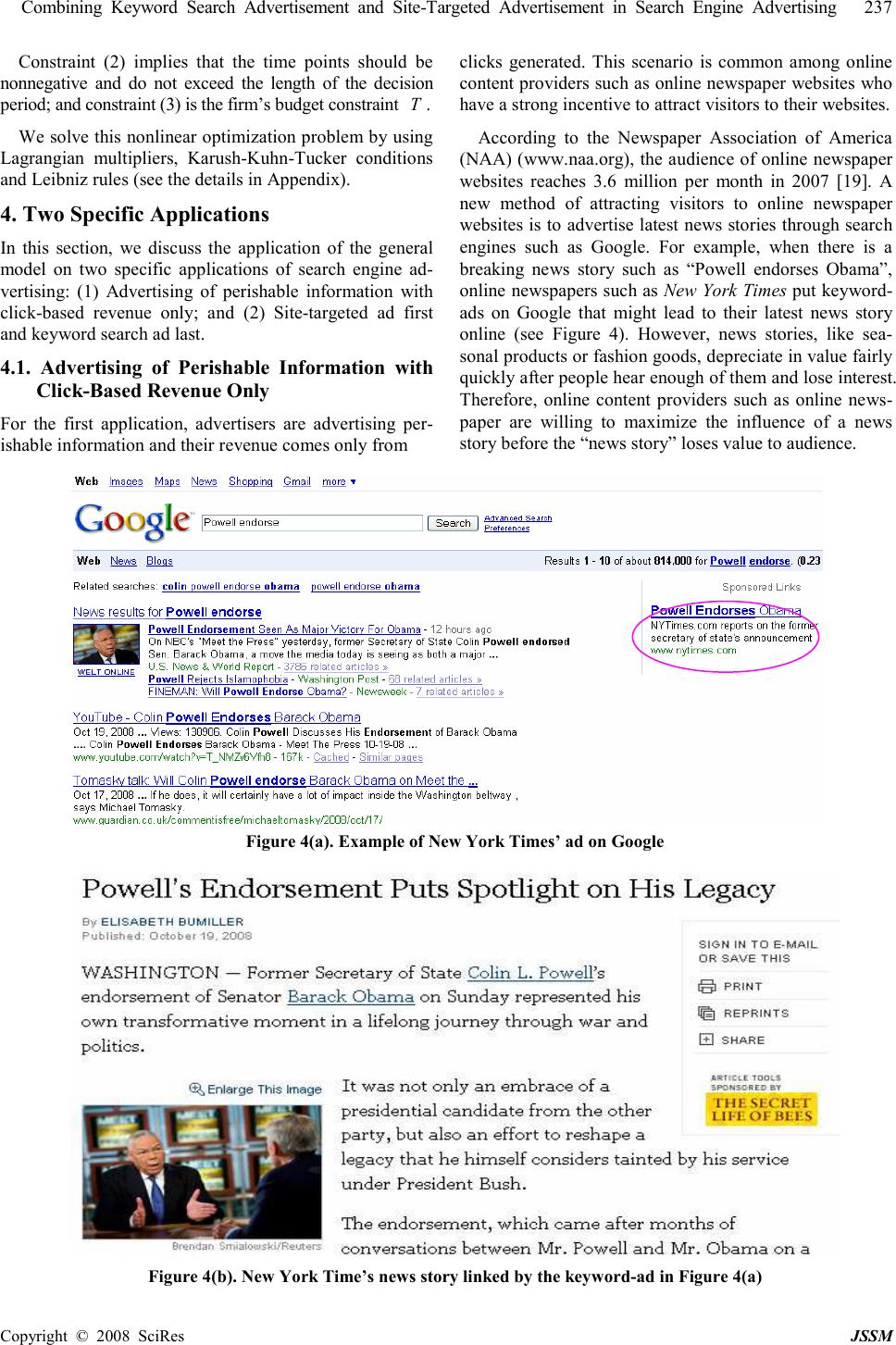

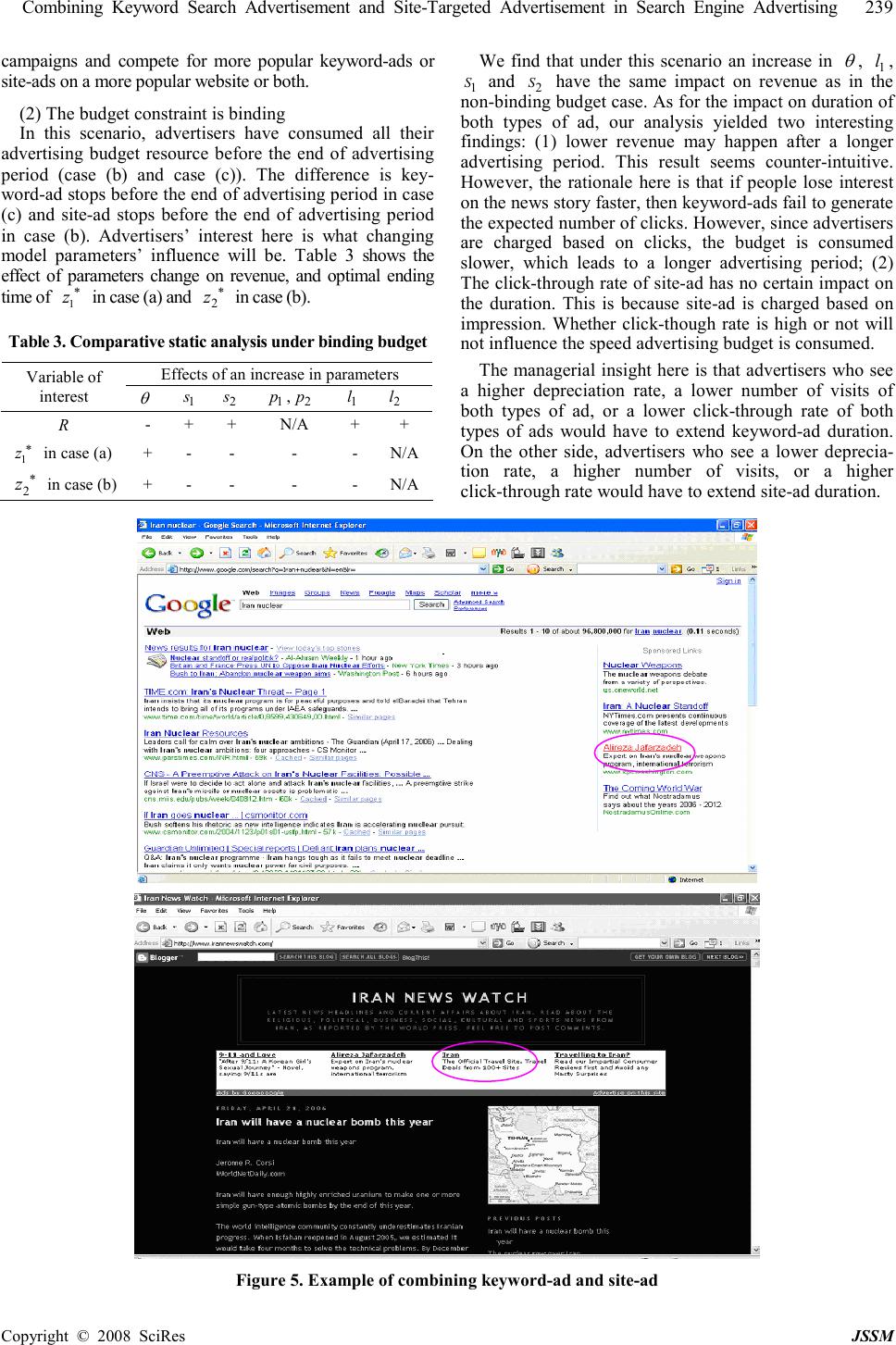

J. Serv. Sci. & Management, 2008,1: 233-243 Published Online December 2008 in SciRes (www.SciRP.org/journal/jssm) Copyright © 2008 SciRes JSSM 1 Combining Keyword Search Advertisement and Site- Targeted Advertisement in Search Engine Advertising Li Chen Department of Operations and Information Management, School of Business, University of Connecticut Email: lchen@business.uconn.edu Received June 3 rd , 2008; revised November 17 th , 2008; accepted November 27 th , 2008. ABSTRACT Internet advertising has seen a strong growth in recent years and search engine advertising has played an important role in that growth. Search engines continue to expand their business by providing new options of advertising. For ex- ample, Google provides a new advertisement mechanism based on cost-per-thousand-impression (CPM) payment called “site-targeted advertisement” in addition to the famous “keyword search advertisement” based on cost-per-click (CPC). While keyword search advertisement is a cost-efficient way of advertising, site-targeted advertisement provides a quicker alternative to expose the ad to a mass population at a higher expense. This paper studies a mixed strategy of optimization by combining these mechanisms to exploit their corresponding advantages. We set up a general model to find optimal starting and ending times for both methods. Closed-form solutions are calculated for two applications: (1) Advertising of perishable information with click-based revenue only; and (2) Site-targeted advertisement first and key- word search advertisement last. Comparative static analysis provides an analysis of properties of each application. We also develop a computational experiment based on Google AdWords to illustrate the application of the model. Keywords: online advertising, search engine, keyword auction, cost per click 1. Introduction An increasingly popular approach for firms to develop e-commerce is to advertise on search engines such as Google, Yahoo, and MSN. For most of people using Internet, search engine websites are a “must-see” when surfing online. A survey from iProspect shows that 56 percent of respondents used search engines at least once a day [1]. Although search engine is a relatively new me- dium for advertising compared with newspaper, TV and radio, search engines provide potential buyers and sellers a worldwide and 24-7 access to each other. Search en- gine advertising has seen a solid and continuous growth in recent years. During the second quarter of 2008, search engine advertising witnessed an increase of 24 percent from the second quarter of 2007 to reach $2.5 billion, around 44 percent of total US online advertising spending [2]. The search engine advertising market can be seen as a duopoly. According to comScore.com, Google took 57 percent of the market in September 2008 and Yahoo took 23.7 percent [3]. In this paper, we base our research on advertising mechanism of Google AdWords, the advertising program of the largest player in this market. Currently Google AdWords provides two types of advertisements: keyword search advertisement and site-targeted advertisement [4]. Keyword search advertisement (hereinafter as “keyword- ad”) refers to advertisements that appear side by side with search results on the Google web pages. Advertisers who are interested in putting this type of ad on Google web pages need to participate in a keyword-ad campaign and win ad slots (see a simplified process in Figure 1). For each ad campaign, Google adopts a modified sec- ond-price auction mechanism to allocate the ad slots. In ranking the advertisements, Google not only considers the bid amount but also the quality of the advertisements. Under this auction mechanism, an advertiser with a higher ranking wins an ad slot but only needs to pay the necessary amount to rank over the advertiser with the next highest ranking. Since keyword-ad is based on a cost-per-click (CPC) payment mechanism, an advertiser only needs to pay for every click on the sponsored link. If no click ever occurs, no payment will be charged. (See Figure 2 for an example of keyword-ad). Google AdWords began Site-targeted advertisement (hereinafter “site-ad”) in April 2005, allowing advertisers to choose individual sites in the Google network where they would like their ads to appear. (see Figure 3 for an example). Register as an AdWords member Create an ad to attract clicks Review and save the ad Choose keywords or web sites Set limits like daily budget Figure 1. Process flow of ad campaign setup  234 Li Chen Copyright © 2008 SciRes JSSM Before the site-ad mechanism was introduced, the only way to advertise through Google was through CPC-based keyword-ad auction. This method was simple and easy to apply, but it had two drawbacks: (1) only visitors who search information through Google had a chance to see the ad and click on it; (2) click fraud may increase the advertising cost [4]. After the introduction of site-ads, Google expected to provide AdWords users with more choices of location of their ads and increase Google’s revenues at the same time. With site-ads available, adver- tisers can be seen more widely over the Internet. The al- location of ad slots in a site-ads auction also uses the modified second-price auction mechanism. However, unlike a keyword auction, advertisers are charged based on a cost-per-thousand- impressions (CPM) payment method rather than cost-per-click (CPC) method. Each time an ad is displayed on a web page, the advertiser will be charged [5]. With the presence of site-ads, advertisers can realize their revenues through CPC-based keyword-ads, CPM- based site-ads, or both. Given these choices, our goal in this paper is to study whether a mixed strategy of com- bining the two ad mechanisms will help advertisers in- crease their revenues. We develop a general budget- con- strained, nonlinear optimization model to maximize ad- vertisers’ revenues using this “mixed strategy”. In the model, we determine starting and ending points for the time intervals during which keyword-ad and site-ad ad- vertising campaigns should hold. These intervals might overlap. After formulating the optimality conditions of the model, we concentrate on the study of two particular scenarios: (1) advertising of perishable information with click-based revenue only; and (2) site-ads first and key- word-ads last. Figure 2. Example of Google AdWords keyword search ads Figure 3. Example of google adwords site-targeted ads (New York Times website) Keyword - ad Site - ad  Combining Keyword Search Advertisement and Site-Targeted Advertisement in Search Engine Advertising 235 Copyright © 2008 SciRes JSSM In the first scenario, we assume that the advertiser only makes revenues from people visiting the advertiser’s web site, which is generated by clicks. Also, we assume that the content on the web site is perishable and its value de- creases over time. The scenario is typical of newspaper websites, where just looking at the ads linking to a news story page does not generate revenues for the newspaper. In the second scenario, we assume that the advertiser starts using site-ads and then switches to keyword-ads without overlapping. This situation applies to advertising of new products or services where the advertiser wants to aggressively expose her ads to a large population of po- tential customers, even though it might be more expen- sive. We find closed-form solutions for both scenarios, and then we perform comparative static analysis to study how the changing model parameters affect the solution. Based on this analysis, we provide some managerial insights under two conditions: non-binding budget and binding budget. Under the condition of non-binding budget, for a manager facing a high content depreciation rate and low number of visits and click-through rate, it would be a bet- ter strategy to open new advertising campaigns and com- pete for more popular keyword-ads or site-ads on a more popular web site or both. Under the condition of binding budget, for the first scenario, advertisers who see a higher depreciation rate, a lower number of visits of both types of ad, or a lower click-through rate of both types of ads would have to ex- tend the keyword-ad duration. For the second scenario, we find that advertisers who see a higher number of visits on site-ad would have to move the switch time earlier, and they would have to delay the switch time while seeing a lower number of visits of site-ad. The remainder of this paper proceeds as follows. Sec- tion 2 provides a review of recent literature in related ar- eas. Section 3 discusses the general model for the mixed strategy of combining both types of ad mechanisms. Sec- tion 4 details the analysis of the two scenarios discussed above and offers numerical examples. Section 5 contains the conclusion. In the Appendix, we present the optimal- ity conditions for the general model. 2. Literature Review Search engine advertising has become a hot topic and attracted significant research interests [4,6,7,10,14,15,16]. There are multiple streams of related literature studying search engine advertising. In particular, Jansen and Mullen [6] provided an extensive review discussing issues such as auction properties, competitive landscape, how to rank ads, how to set slot prices, payment mechanisms, etc. Even though they considered three types of participants: content providers, search engines and searchers; we only consider the point of view of the content providers who want to optimize their revenues subject to a budget con- straint. We review the following areas that are more re- lated to our research. 2.1. Advertising Allocation Mechanisms In search engine advertising, auction is the major mecha- nism to allocate ad slots. Feng and Bhargava [7] used simulation to study four allocation mechanisms of ad slots, including those used by Overture (Yahoo) and Google AdWords. They found that performance of mechanisms used by Yahoo and Google is better under certain scenario, and their performance also depended on the degree of correlation between providers’ willingness to pay and relevance. Edelman et al. [8] focused on “generalized second-price” (GSP) auction, in which the bidder who wins an ad slot only needs to pay the next highest bidders’ price plus an increment. GSP is attractive to search engines because it helps to maximize profit. In addition, Feng et al. [9] developed a simultaneous pooled auction (SPA) mechanism and showed that using reserve price in SPA significantly in- creased a search engine’s revenue. 2.2. Payment Mechanism There are multiple payment methods in search engine advertising, such as cost-per-click, cost-per- thousand- impression (CPM) and cost-per-action [10]. While CPM comes from traditional print media, cost-per-click and cost-per-action are based on the search engines’ and ad- vertisers’ measurement. Hu [11] applied the economic theory of incentive contracts to show that perform- ance-based pricing models improve effectiveness of ad- vertising campaigns. After investigating the implementa- tion of paid placement strategies, Weber and Zheng [12] found that revenue-maximizing search engines ranked ads on a weighted average of relative performance and bid amount. Kumar et al. [13] studied an interesting problem of the optimal advertising schedule in ads slots of the web sites based on a hybrid pricing model. 2.3. Bidder Strategies Advertisers need to determine how to respond to competi- tion in auctions. One common observation is cycle bidding, where bidders revise their bids to compete for ad slots (Edelman and Ostrovsky 2007 [14] and Zhang and Feng [15]). One possible explanation is gap jamming, which refers to the behavior of bidders’ raising bids to some point just below competitors’ bids. When gap jamming is pre- sent, competitors will be charged for the highest possible amount. Another important strategy for bidders is how to allocate their funds across advertising campaigns such as keyword-ad campaigns. Özlük and Cholette [16] suggested a model for advertisers who have a fixed daily budget limit to select keywords to maximize productivity and then determine the bid for each keyword selected. 2.4. Optimization in Internet Advertising Internet advertising also faces optimization problems. For example, Dewan et al. [17] found a tradeoff between ads and content for web sites: more ads generate more revenue but may turn viewers off. Their findings suggest that websites put fewer ads and more content, and get com- pensated for by future profits. Another example comes from Fruchter and Dou [18], which studied how to dy-  236 Li Chen Copyright © 2008 SciRes JSSM namically assign budget of banner ads between the two types of portals (generic vs. specialized). Our work is different from previous research in that we consider a mixed keyword-ad and site-ad strategy, we only consider the content provider’s point of view, we provide a new budget-constrained, nonlinear optimization model to maximize advertisers’ revenues, and we study two par- ticular scenarios that have not been considered before: advertising of perishable information with click-based revenue only, and site-ad first and keyword-ad last. 3. General Model In this paper, we develop an optimization model of a mixed strategy which combines the keyword-ad and site-ad mechanisms to help advertisers maximize their revenue. Keyword-ad is a cost-efficient advertising strat- egy because advertisers are only charged for clicks on their ads. Therefore, we regard keyword-ad as a “waiting strategy” because only visitors with relatively strong in- terest will search information through search engines and advertisers have no control of the number of search re- quests and clicks based on these visits. For site-ad, we regard it as a “showing strategy” because after putting an ad on a targeted website, viewers of the website are ex- posed to that site-ad even if they do not plan to search that information. Compared with keyword-ad, site-ad is a more aggressive approach in terms of generating a large number of impressions in a short time, but the related expense is usually also higher. In our model, we assume that there is fixed time period of length T during which the decision maker will decide the starting and ending times of each type of ad mecha- nisms. We denote by 1 y and 3 y the starting times of keyword-ad and site-ad respectively; and by 2 y and 4 y the ending times of keyword-ad and site-ad, respectively. Notice that 1 3 0 yy T ≤ ≤≤ , 2 4 0 yy T ≤≤≤ , and the two intervals may overlap. We denote the time vector of deci- sion variables by Y= (y 1 ,y 2 ,y 3 ,y 4 ). Our model uses a set of exogenous smooth functions as described in Table 1. The idea is to use these functions to capture the behavior of the searchers as well as the pay- ment mechanism of the advertiser. We use subscript “1” to refer to CPC-based keyword-ads and “2” to refer to CPM-based site-ads. Consistent with previous work [7], we assume that click-through rate only depends on the location of ad slot on the web page. Also we assume that the click-through rate of keyword-ad is higher than that of site-ad. This is because people who search for the infor- mation are more likely to click on the ad. Although there maybe a higher number of clicks generated from site-ads, the click-through rate may not be as high as that of key- word-ad. For example, if 100 people search information of “2008 Olympics”, and there are 30 people click on the keyword-ad, then the click-through rate is 30 percent. At the same time, there maybe 1000 people see the site-ad of Table 1. Notation used in the general model Ad Type Visits in time period t Payment per ad in time period t Click-through rate in time period t Keyword 1 ( ) S t P 1 (t) 1 ( ) l t Site 2 ( ) S t P 2 (t) 2 ( ) l t the same content but only 100 people click the ad. Al- though the site-ad generates more clicks (100> 30), the click-through rate is only 10 percent, smaller than that of keyword-ad (30 percent). Our goal is to maximize advertiser’s total revenue ( ) R Y through the period for a given choice of starting and ending times 12 3 4 ( ,,,) Yy yyy = . In addition, we assume that the advertiser is subject to a budget limit B , that is, the advertiser cannot spend more than B through the whole period. We compute total revenue ( ) R Y as follows: 2 4 11 122 1 3 ()( )( )( )( ) y y y y RYrStltdtStltdt = + ∫ ∫ 2 4 2 12 1 3 ( )( ) y y y y rSt dtStdt + + ∫ ∫ In the definition of total revenue, 1 ( ) S t denotes the number of visits on the keyword-ad in time period t and 2 ( ) S t denotes to the number of visits on site-ad in time period t. 1 1 ( )() St lt denotes the number of clicks gener- ated from keyword-ad in time period t , and 2 2 ( )( ) Stlt denotes to the number of clicks generated from site-ad in time period t . We take the integral to calculate the total number of clicks and total number of visits during the whole ad campaign duration. Finally, we multiply by r1 and r2 the integrals, respectively, to obtain the total reve- nue. To account for the budget constraint, we use the expression: 2 4 1 1122 1 3 ( )()( )( )( ) y y y y Stltpt dtStpt dt + ∫ ∫ where 1 11 ( )( )( ) St ltpt denotes the cost of keyword-ad and 2 2 ( )( ) St pt denotes the cost of site-ad. As before, the integrals are used to calculate the total amount of payment. The resulting model is the following: 2 4 11 122 1 3 ()( )( )( )( ) y y Yy y MaxRYrSt ltdtSt ltdt = + ∫ ∫ 2 4 2 12 1 3 ( )( ) y y y y rSt dtSt dt + + ∫ ∫ (1) subject to: 0, 1,...,4 i y Ti≤ ≤= (2) 2 4 1 1122 1 3 ( )()( )( )( ) y y y y Stlt ptdtSt ptdtB + ≤ ∫ ∫ (3)  Combining Keyword Search Advertisement and Site-Targeted Advertisement in Search Engine Advertising 237 Copyright © 2008 SciRes JSSM Constraint (2) implies that the time points should be nonnegative and do not exceed the length of the decision period; and constraint (3) is the firm’s budget constraint T . We solve this nonlinear optimization problem by using Lagrangian multipliers, Karush-Kuhn-Tucker conditions and Leibniz rules (see the details in Appendix). 4. Two Specific Applications In this section, we discuss the application of the general model on two specific applications of search engine ad- vertising: (1) Advertising of perishable information with click-based revenue only; and (2) Site-targeted ad first and keyword search ad last. 4.1. Advertising of Perishable Information with Click-Based Revenue Only For the first application, advertisers are advertising per- ishable information and their revenue comes only from clicks generated. This scenario is common among online content providers such as online newspaper websites who have a strong incentive to attract visitors to their websites. According to the Newspaper Association of America (NAA) (www.naa.org), the audience of online newspaper websites reaches 3.6 million per month in 2007 [19]. A new method of attracting visitors to online newspaper websites is to advertise latest news stories through search engines such as Google. For example, when there is a breaking news story such as “Powell endorses Obama”, online newspapers such as New York Times put keyword- ads on Google that might lead to their latest news story online (see Figure 4). However, news stories, like sea- sonal products or fashion goods, depreciate in value fairly quickly after people hear enough of them and lose interest. Therefore, online content providers such as online news- paper are willing to maximize the influence of a news story before the “news story” loses value to audience. Figure 4(a). Example of New York Times’ ad on Google Figure 4(b). New York Time’s news story linked by the keyword-ad in Figure 4(a)  238 Li Chen Copyright © 2008 SciRes JSSM As mentioned earlier, it is difficult for a keyword-ad strategy to rapidly generate the expected level of attention because it is a “waiting strategy” where advertisers have to wait people viewing their ads and clicks on them. In this scenario, a mixed strategy that combines site-ad with keyword-ad may be a better alternative. The rationale is that visitors of the targeted site are exposed to the ad of the news story. These visitors might not know the news or they know but have not an interest strong enough to go to Google.com to search “Powell endorses Obama”. How- ever, they are likely to click the ad linked to the online newspaper to read the story. In other words, such a strat- egy is more likely to impress potential visitors whose search cost of news is relatively high but are willing to read the news when a link is in front of them. Under this scenario, our main concern is to find the op- timal ending time of both types of ads to maximize of the advertisers’ revenue given a budget constraint. 4.1.1. Modified Mathematical Model We make two modifications on the general model from Section 3 to meet requirements of this specific application: (1) we assume that advertisers want to begin both key- word-ad and site-ad at the beginning of the advertising campaign. Thus, we set the starting time of both key- word-ad and site-ad to zero, which implies that both types of ad will be adopted from the beginning; and (2) we as- sume that the advertisers in this specific application are interested only in the number of the clicks on their web- site. Impressions of both keyword-ad and site-ad on viewers will not bring value to the advertisers. For that reason, we only consider the first expression in the defini- tion of ( ) R Z in (1). We use z 1 and z 2 to denote the ending time of keyword- ad and site-ad respectively, and 1 2 ( ,) Zz z = to denote the corresponding decision vector. The general model is modified as follows: 1 2 11 122 0 0 (){()()( )( )} z z MaxRZrSt lt dtSt ltdt = + ∫ ∫ (4) subject to: 1 2 0 , z zT ≤ ≤ (5) 1 2 11 122 0 0 ( )( )( ) z z pSt lt dtpStdtB + ≤ ∫ ∫ (6) We assume that 1 ( ) S t decreases exponentially with a de- preciation rate θ so that 1 1 ( ) t Stse θ − = , where 1 s denotes to the number of initial visits. A higher value of θ indicates a fast speed people lose interest on the information. We also assume 2 ( ) S t is fairly stable in terms of the number of visits per unit of time so we can use average number of impressions 2 S as an approximation. As before, the click-through rate is assumed to be relatively stable at 1 l and 2 l during the whole advertising period. In this study, we only consider situations under which both 1 z ∗ and 2 z ∗ are positive. Using Karush-Kuhn- Tucker condition, we get closed forms for three optimal solutions * * 1 2 ( ,) z z with economic meaning. a) * * 1 2 zz T = = In this case, the optimal ending time for both types of ads is the end of the advertising period, which implies that the budget constraint is not binding. b) 1 z T ∗ = and 211 122 1 {(1)} / T z Be ps lps θ θ ∗− − = −− . In this case, the best choice is to stop the site-ad before the end of the advertising period, and let keyword-ad con- tinue to the end. c) 2 2 11 11 ( ) 1 log{1 } Bps T zps l θ θ − ∗ − = −− and * 2 z T = . In this case, the best choice is to stop keyword-ad be- fore the end of the advertising period and let site-ads con- tinue to the end. 4.1.2. Comparative Static Analysis We investigate the impact of changes of parameter values under two conditions: whether budget constraint is bind- ing or not. The rationale to discuss the scenario of non-binding budget is that for large online content pro- viders such as New York Times, their interests are proba- bly not saving money but fully utilizing the budget to generate attention and clicks, especially when a news story is still of interesting to public. (1) The budget constraint is not binding Let 1 11 122 (1 ) T BBeps lpsT θ θ − − = −−− % denotes re- maining budget. As mentioned above, we are interested to see how changes of parameters will influence advertisers’ revenue and remaining budget. Comparative analysis on parameters can shed lights on what decision to make (see Table 2). We see that an increase in on θ leads to less revenue and a higher remaining budget, while an increase in 1 l , 1 S and 2 S leads to more revenue and less remaining budget. The result is intuitive because an increase in θ implies that public’s interest on the online content such as a news story depreciates faster, and fewer clicks are gen- erated. On the other hand, increases in 1 l , 1 S and 2 S imply that either more people are interested in the news story or more people are exposed to the site-ad or people who see the keyword-ad are more likely to click on the ad and observe the information linked to the ad. Obviously, all these changes will lead to more revenue and less re- maining budget. Using these results, a manager can determine which strategy to choose. For example, in case of a high depre- ciation rate and low number of visits and click-through rate, advertisers should bid aggressively so as to open new advertising Table 2. Comparative static analysis under non-binding budget Effects of an increase in Variable of interest θ 1 s 2 s 1 p , 2 p 1 l 2 l R - + + N/A + + B % + - - - - N/A  Combining Keyword Search Advertisement and Site-Targeted Advertisement in Search Engine Advertising 239 Copyright © 2008 SciRes JSSM campaigns and compete for more popular keyword-ads or site-ads on a more popular website or both. (2) The budget constraint is binding In this scenario, advertisers have consumed all their advertising budget resource before the end of advertising period (case (b) and case (c)). The difference is key- word-ad stops before the end of advertising period in case (c) and site-ad stops before the end of advertising period in case (b). Advertisers’ interest here is what changing model parameters’ influence will be. Table 3 shows the effect of parameters change on revenue, and optimal ending time of 1 z ∗ in case (a) and 2 z ∗ in case (b). Table 3. Comparative static analysis under binding budget Effects of an increase in parameters Variable of interest θ 1 s 2 s 1 p , 2 p 1 l 2 l R - + + N/A + + 1 z ∗ in case (a) + - - - - N/A 2 z ∗ in case (b) + - - - - N/A We find that under this scenario an increase in θ , 1 l , 1 S and 2 S have the same impact on revenue as in the non-binding budget case. As for the impact on duration of both types of ad, our analysis yielded two interesting findings: (1) lower revenue may happen after a longer advertising period. This result seems counter-intuitive. However, the rationale here is that if people lose interest on the news story faster, then keyword-ads fail to generate the expected number of clicks. However, since advertisers are charged based on clicks, the budget is consumed slower, which leads to a longer advertising period; (2) The click-through rate of site-ad has no certain impact on the duration. This is because site-ad is charged based on impression. Whether click-though rate is high or not will not influence the speed advertising budget is consumed. The managerial insight here is that advertisers who see a higher depreciation rate, a lower number of visits of both types of ad, or a lower click-through rate of both types of ads would have to extend keyword-ad duration. On the other side, advertisers who see a lower deprecia- tion rate, a higher number of visits, or a higher click-through rate would have to extend site-ad duration. Figure 5. Example of combining keyword-ad and site-ad  240 Li Chen Copyright © 2008 SciRes JSSM We have observed real examples of using both types of ads (see Figure 5). However, it will be easier to show the implication of our model using real data from advertising campaigns. To illustrate our model to advertisers who want to ap- ply the “mixed strategy”, we use a numerical experiment to explain the general solution methodology. We put an ad of “Enjoy everyday in Shanghai 1 ” which links to the top news story on entertainment in Shanghai to an online version of a local newspaper www.shanghaistar.com. In order to maximize the value of the news story, we com- bine keyword-ad and site-ad campaign through Google AdWords. Following the model, we begin both types of ads at the same time and our purpose is to obtain the op- timal stop time for both advertising strategies. Data are collected from Jan 9 th , to Feb 22 nd , 2006 from Google AdWords records of both ads. Before we apply the model, we use the data to validate our exponential decay assumption of the keyword-ad visit S 1 (t) and site-ad visit S 2 (t) functions. Results of MS Excel to estimate S 1 (t) using the best-fit exponential curve (red curve in Figure 6) and estimate S 2 (t) using average (red curve in Figure 7) fit our assumptions well. (See Figure 6 and Figure 7). Then we used the detailed information about both keyword-ad and site-ad to calculate values of parameters in our model (see Table 4). Finally, we set time period 100 T = days and the budget limit $40 B = . Advertisers who want to apply our model just need to set their own numerical values of these exogenous variables. The optimal solution is * 1 100 y=, * 2 76.32 y= and the estimated number of clicks is 44. Thus, the optimal decision for advertisers is to hold the keyword-ad to the end of the advertising period, but end the site-ad around two and half months. 4.2. Site-Targeted Advertisement First, Keyword Search Advertisement Last For second specific application, advertisers want to start their advertising campaign by using site-ad to aggres- sively impress the public and then switch to keyword-ad without overlapping. This strategy can be applied to ad- vertisement of new products and services where the ad- vertiser wants to expose her ads to a mass population of potential customers more quickly. In a global economy with intense competition, firms face Table 4. Summary of google adwords’ report Ad Type Clicks Impression CTR (percent) CPC CPM Keyword 9 1276 0.69 $0.05 - Site 8 2959 0.27 - $7.66 1 Shanghai is a big city in China. strong pressure to continuously exploit new product or services and effectively advertising those new products and services to potential consumers. At the beginning period of advertising, companies are not only interested in how many purchases have been made, but also how many consumers are aware of the new product or services. In other words, either a visit to the advertiser’s website or an impression on the ad to potential customers brings bene- fits to the company. Consumers who visit firms’ website may immediately make a purchase, while potential con- sumers exposed to the ad without clicking may come back and purchase the product or service later. Site-ad meets the requirement to wildly and quickly impress the public in the early stage of advertising period. Although keyword-ad is not an effective marketing tool at the beginning because potential customers are unfamiliar with the new product or brand, it is a cost-efficient mar- keting method after certain level of awareness is achieved. Therefore, we suggest that site-ad first and keyword-ad last might be a better strategy for advertisers. Then the question for advertisers is how to determine optimal switching time from site-ad to keyword-ad. 4.2.1. Modified Mathematical Model For this specific application, we assume that advertisers will begin with site-ad only, and then switch to key- word-ad without overlapping. To meet requirements of this specific application, we modify the general model in section 3 as follows: (1) we set the start time of site-ad as zero and the ending time of keyword-ad as the end of the whole advertising period T ; (2) we use z as the switching time of a site-ad and a keyword-ad. The general model is modified as follows: Max 11 122 0 (){( )( )} T z z RzrSt ldtSt ldt = + ∫ ∫ 2 12 0 {( )( )} T z z rSt dtSt dt + + ∫ ∫ (7) subject to: 0 z T ≤ ≤ (8) 11122 0 ( )( ) T z z pStl dtpStdtB + ≤ ∫ ∫ (9) Similar to the application of advertising perishable in- formation with click-based revenue only, we estimate the visit of site-ads using average visits 2 2 ( ) S ts = and steady click-through rate 1 l and 2 l over the advertising period [0, ] z ∗ .We also assume that 1 ( )() Stsg z ′ = +, where ( ) g z refers to visits due to awareness of site-ad. A linear function () g zazb = + is used to estimate the value of 1 ( ) S t . The trade-off in this model is that longer site-ads duration leads to a higher number of impressions at the beginning of keyword-ad, but runs out the budget more rapidly at the same time. We get two optimal solutions for switching time z ∗ .  Combining Keyword Search Advertisement and Site-Targeted Advertisement in Search Engine Advertising 241 Copyright © 2008 SciRes JSSM Figure 6. Summary of keyword-ad impression Figure 7. Summary of site-ad impression a) 221 1 1 1 ( ) 2 spplbsaT zap l ∗ ′ −+−− ∆ = b) 221 1 1 1 ( ) 2 spplbsaT zap l ∗ ′ −+−+ ∆ = where 2 1 11 1221 1 4(()) (()) ap lbsp l TBspp lbsaT ′ ′ ∆ =+−+−+− . In both cases, advertisers switch from site-ads towards keyword-ads at z ∗ . 4.2.2. Comparative Static Analysis Similar to the case in section 4.1, we investigate the impact of changing parameter values under two conditions: whether the budget constraint is binding or not. We also assume here that advertisers want to make full use of the budget to maximize the advantages of both keyword-ad and site-ad. (1) The budget constraint is not binding Let 2 2 1 122 (()()()) 2 a BBp lsbTzTzpsz ′ = −+−+−− % denotes remaining budget. In this scenario, advertisers fail to use up their advertising budget on site-ad. Table 5 shows how an increase in value of parameters will influ- ence both revenue and remaining budget. We see from the table that only 2 s has impact on both revenue and remaining budget. Intuitively, when the budget is not used up, an increase in visits of site-ad 2 s to some value but lower than 2 / Bp T will consume more advertising budget and increase revenue. Therefore, Table 5. Comparative static analysis under non- binding budget Effects of an increase in Variable of interest a s ′ , b 2 s 1 p , 2 p 1 l 2 l R N/A N/A + N/A N/A + B % N/A N/A - - N/A N/A advertisers with advertising dollar left can transform budget resource into revenue by selecting a more popular web site or start new site-ads. (2) The budget constraint is binding Under the condition that budget constraint is binding, advertiser is interested to see how change in value of one parameter will influence the optimal switching time, such as moving the optimal switching time earlier or later (see Table 6). We can see from Table 6 that an increase in site-ads visits 2 s will force the advertiser to move the optimal switch time earlier because the expected level of aware- ness is achieved earlier in time and advertising resources is used more quickly. On the other hand, an increase of value of parameters s ′ or b have the opposite effect on switch time although they have the same effect on revenue as S 2 . However, an increase in value of parame- ters like payment for each click p 1 and payment for each impression p 2 has uncertain effect on switch time because the closed-form solution is not available. Table 6. Comparative static analysis under binding budget Effects of an increase in parameters Variable of interest a s ′ , b 2 s 1 p , 2 p 1 l 2 l R + + + N/A + + z ∗ ? + - ? ? N/A *Question mark means no close-form solution available Table 7. Parameters used in numerical example Parameter Parameter Parameter 1 r =$0.25 2 r =$10.00 per thousand a =20 s ′ =50 2 s =7500 B =$250 1 p =$0.20 2 p =$8.00 per thousand b =40 1 l =1% 2 l =0.03% T =20  242 Li Chen Copyright © 2008 SciRes JSSM We use a numerical example to illustrate the applica- tion of our model. Similar to the application of advertising perishable information with click-based revenue only, we can calculate values of parameters using the information from search engines. Using the values in Table 7, we ob- tain that the switch time is 4.1 z ∗ = and the revenue is $342.10 for the advertiser. 5. Conclusions Internet advertising, especially search engine advertising has quickly become vital for businesses to succeed in e-commerce. Google, the largest search engine, provides site-targeted ads to advertisers in addition to its traditional pay-per-click model. In spite of the fact that more and more firms put site-targeted ads on Google-networked websites, very little research has attempted to analyze how advertisers can make use of this new type of ads such as a mixed strategy of combining it with the CPC-based key- word search advertisement. This research attempts to fill this gap by suggesting and formally modeling the strategy of combining both types of ads. We developed a general model to address the research problem of what is the optimal time to start and end both keyword-ads and site-ads. This model would help adver- tisers to maximize their revenues. We modify the general model for two specific scenarios: (1) Advertising of per- ishable content with click-based revenue only; and (2) Site-ads first and keyword-ads last. We provide closed-form solutions for these two applications and pro- vide managerial insights under the situation of bind- ing-budget and non-binding budget. Computational ex- periment and numerical example is also provided to illus- trate the implementation of the model. This research focuses on the mixed strategy of both keyword-ad and site-ad in Google AdWords framework. As for future research, it will be interesting to study strategies of advertising across different search engines when they adopt different mechanisms. Another promis- ing area will be how search engines can help advertisers when they observe that advertisers using a mixed strategy. 6. Acknowledgment The author would like to thank Professor Manuel Nunez of University of Connecticut for his great help on im- proving the early versions of this paper. REFERENCES [1] Internet Resource, “Search engine user attitudes”, April - May 2004, www.iProspect.com [2] Internet Resource, “IAB internet advertising revenue report,” http://www.iab.net/media/file/IAB_PWC_2008_6m.pdf. [3] Internet resource, “comScore releases september U.S. search engine rankings,” www.comscore.com, http://www.comscore.com/press/release.asp?press=1805. [4] B. Jansen, “Click fraud,” IEEE Computer, Vol. 40, No. 7, pp. 85 - 86. [5] Internet resource, “Google adwords online introduction,” http://adwords.google.com/support/bin/answer.py?answer= 19657&topic=342. [6] B. Jansen and T. Mullen, “Sponsored search: An overview of the concept, history, and technology,” International Journal of Electronic Business, Vol. 6, No 2, pp. 114 - 131, 2008. [7] J. Feng, H. K. Bhargava, and D. M. Pennock, “Implementing sponsored search in web search engines: Computational evaluation of alternative mechanisms,” INFORMS Journal on Computing, Vol. 19, No. 1, pp. 137 - 148. Winter 2007. [8] B. Edelman, M. Ostrovsky, and M. Schwarz, “Internet advertising and the generalized second-price auction: Selling billions of dollars worth of keywords,” American Economic Re- view, Vol. 97. No. 1. pp 242 - 259, March 2007. [9] J. Feng, Z. M. Shen, and R. L. Zhan, “Ranked items auctions and online advertisement,” Production and Operation Management, Vol. 16. No. 4. pp. 510 - 522. July - August 2007. [10] K. Asdemir, N. Kumar, and V. Jacob, “Internet advertising pricing models,” Technique report, School of Management, The University of Texas at Dallas, 2002. [11] Y. Hu, “Performance-based pricing models in online ad- vertising,” Ph.D. dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, 2005, AAT 0807658. [12] T. A. Weber and Z. Zheng, “A model of search intermediaries and paid referrals,” Information Systems Research, Vol. 18, No. 4, pp. 414 - 437, December 2007. [13] S. Kumar, M. Dawande, and V. S. Mookerjee, “Optimal scheduling and placement of internet banner advertisements,” IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering, Vol. 19, No. 11, pp. 1571 - 1584, November 2007. [14] B. Edelman and M. Ostrovsky, “Strategic bidder behavior in sponsored search auctions,” Decision Support Systems, Vol. 43, No. 1, pp. 192 - 198. [15] J. Feng and M. Zhang, “Price cycles in online advertising auctions,” Proceedings of the 26 th International Conference on Information Systems (ICIS), Las Vegas, NV, December 2005. [16] Ö. Özlük and S. Cholette, “Allocating expenditures across keywords in search advertising,” Journal of Revenue and Pricing Management, Vol. 6, pp. 347 - 356. [17] R. M. Dewan, M. L. Freimer, and J. Zhang, “Management and valuation of advertisement-supported web sites,” Journal of Management Information Systems, Vol. 19, No. 3, pp. 87 - 98, Winter 2002/2003. [18] G. E. Fruchter and W. Dou, “Optimal budget allocation over time for keyword ads in web portals,” Journal of Op- timization Theory and Applications, Vol. 124, No. 1, pp. 157 - 174, January 2005. [19] Internet resource, “Online newspaper viewership reaches record in 2007,” www.naa.org, http://www.naa.org/PressCenter/SearchPressReleases/2008/ Online-Newspaper-Viewership. aspx.  Combining Keyword Search Advertisement and Site-Targeted Advertisement in Search Engine Advertising 243 Copyright © 2008 SciRes JSSM Appendix We use the Karush-Kuhn-Tucker conditions to solve the general model of Equation (1) on page 3. Step 1: We get the following Lagrangian equation: 1 2 3 4 0 12 3 4 (,,,,,, ,, ) L yyyy λ λλ λ λ = 242 4 131 3 11 122212 {( )( )()()}{( )( )} yyy y yyy y rStltdtStlt dtrSt dtStdt ++ + ∫∫∫ ∫ 2 4 1 3 01 1122 {( )( )( )( )()} y y y y BStltpt dtStpt dt λ + −+ ∫ ∫ 11 2233 44 ()() () () T yT yT yT y λ λλλ +− +−+−+− Step 2: Using Leibniz rule, we get the Kuhn-Tucker conditions: 1 11 101 111 12111 1 1 ( )(){( )}()0;0;0; L L S ylypyrSyryy y y λ λ ∂ ∂ =− −− ≤≥= ∂ ∂ 1 21 21012122222 2 2 ( )( ){()}( )0;0;0; L L Syl yrp ySy ryy y y λ λ ∂ ∂ =−+− ≤≥= ∂ ∂ 2 302312 32 32333 3 3 ( ){( )( )}( )0;0;0; L L SypyrlySy ryy y y λ λ ∂ ∂ =−−−≤≥= ∂ ∂ 2 412 40242 42444 4 4 ( ){( )( )}( )0;0;0; L L SyrlypySyryy y y λ λ ∂ ∂ =−+−≤≥= ∂ ∂ 2 4 1 3 1 112200 0 0 ( )( )( )( )( )0;0;0; y y y y L L BStlt ptdtStptdt λ λ λ λ ∂ ∂ = −−≥≥= ∂ ∂ ∫ ∫ 1 1 1 1 1 0; 0;0; L L T y λ λ λ λ ∂ ∂ = −≥≥= ∂ ∂ 2 2 2 2 2 0; 0;0; L L T y λ λ λ λ ∂ ∂ = −≥≥= ∂ ∂ 333 3 3 0; 0;0; L L T y λ λ λ λ ∂ ∂ = −≥≥= ∂ ∂ 4 4 4 4 4 0; 0;0; L L T y λ λ λ λ ∂ ∂ = −≥≥= ∂ ∂ Since we only consider solutions with economic meanings, we make several restrictions on both ' y s and ' s λ : (1) 1 λ and 3 λ cannot be positive, which means no advertisement. (2) 1 y is always less than or equal to 2 y , and 3 y is always equal to or less than 4 y . (3) One of 1 y and 3 y must equal to zero, which makes sure that at least one type of ads begin. Let 1 11 ( ) ( )( )( ) h t St ltpt t ∂= ∂ , 2 2 ( ) ( )( ) g t St pt t ∂= ∂ , 110 112 ( )( )(()) ftl tp trr λ =− + , 2110 12 ( )( )(( )) ftl trp tr λ = −+ , 3021 22 ( )( )( ) f tptrltr λ =− + , 41 2022 ( )( )() ftrltp tr λ = −+ . Step 3: Assume the reverse function of ( ) f t i , 1,2,3,4 i = , exist and ( ) g t and ( ) h t exist, we get closed-form solution as followings: When the budget condition is not binding: 1) 1 234 0 0 yyTyyT = == = ; When the budget condition is binding, there are 14 possible cases: 2) 1 1 2 34 0((0)); yyyyhBh − = = ==+ 3) 1 1 3 42 0((0)); yy yy gBg − = ===+ 4) 1 1 324 0(()(0)(0)); yyyTyhBg Tgh − = ===−++ 5) 1 1 324 0((0)(0)( )); yyygBghh TyT − = ==++−= 6) 1 1243 0((0)( )()) yyyTyhBgg Th T − == ==+−− ; 7) 1 12 43 ((0)( )( ))0 ygBhgTh TyyTy − =+−−= == ; 8) 1 1 3 0(0) 2,4 i i y yy fi − = === 9) 1 1 0(0), 2,3,4 i i yy fi − = == 10) 1 1 4 0(0), 2,3 i i yyfiy T − = === 11) 1 1 2 0(0), 3,4 i i yyTyfi − = = == 12) 12 3 (0), 1,40 i i yfiyTy − === = 13) 13 (0), 1,2,40 i i y fiy − = == 14) 134 (0), 1,20 i i yfiyy T − === = 15) 14 (0), 1,2,3 i i yfiy T − = == The revenue function: 2 4 1 3 11 122 {( )( )( )( )} y y y y RrStlt dtStlt dt = + ∫ ∫ 2 4 1 3 2 12 {( )( )} y y y y rSt dtSt dt + + ∫ ∫ The remaining budget 2 4 1 3 1 1122 ( )( )( )( )( )} y y y y BBStltptdtSt ptdt = −− ∫ ∫ % 1 324 ()()( )() Bg yh yg yh y = ++−− (a) Starting time 1 11 11112 1 ( )()()0; RSylyrSy r y ∂ = −−< ∂ 11 11 111 1 1 ( ) ( )()( )0; Bg ySy lypy y y ∂ ∂ = => ∂ ∂ % 2 3131232 3 ( )( )( )0; RSyly rSy r y ∂ = −−< ∂ 32 323 3 3 ( ) ( )( ) 0; h y BSy p y y y ∂ ∂ = => ∂ ∂ % which shows an increase in starting time decreases revenue but increases the remaining budget. (b) Ending time 1 21 211 22 2 ( )()()0; RSyly rS y r y ∂ =+ > ∂ 21 21 2 1 2 2 2 ( ) ()( )( )0; Bg yS y l yp y y y ∂ ∂ = −=−< ∂ ∂ % 2 42412 42 4 ( )( )()0; RSy lyrSyr y ∂ =+> ∂ 42 42 4 4 4 ( ) ( )( )0; Bh yS y p y y y ∂ ∂ = −=−< ∂ ∂ % which shows that increase in ending time increase revenue but decrease the remaining budget. Specific problems like the two problems discussed in Section 4 can be solved using the approach above. |