Health

Vol.5 No.1(2013), Article ID:26974,10 pages DOI:10.4236/health.2013.51015

Maternity or catastrophe: A study of household expenditure on maternal health care in India

![]()

1Centre for the Study of Regional Development, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, India

2Global Health and Social Care Unit, School of Health Sciences and Social Care, University of Portsmouth, Portsmouth, UK; *Corresponding Author: aadigeog@gmail.com

Received 11 November 2012; revised 13 December 2012; accepted 21 December 2012

Keywords: Out-of-Pocket Payments; Maternal Health Care; Poverty; NSSO; Catastrophic Expenditure

ABSTRACT

Using data from 60th round of the National Sample Survey, this study attempts to measure the incidence and intensity of “catastrophic” maternal health care expenditure and examines its socio-economic correlates in urban and rural areas separately. Additionally, it measures the effect of maternal health care expenditure on poverty incidence and examines the factors associated with such impoverishment due to maternal health care payments. We found that maternal health care expenditure in urban households was almost twice that of rural households. A little more than one third households suffered catastrophic payments in both urban and rural areas. Rural women from scheduled tribes (ST) had more catastrophic head counts than ST women from urban areas. On the other hand, the catastrophic head count was greater among illiterate women living in urban areas compared to those living in rural areas. After adjusting for out-of-pocket maternal health care expenditure, the poverty in urban and rural areas increased by almost equal percentage points (20% in urban areas versus 19% in rural areas). Increasing education level, higher consumption expenditure quintile and higher caste of women was associated with increasing odds of impoverishment due to maternal health care expenditure. To reduce maternal health care expenditure induced poverty, the demand-side maternal health care financing programs and policies in future should take into consideration all the costs incurred during prenatal, delivery and postnatal periods and focus not only on those women who suffered catastrophic expenditure and plunged into poverty but also those who forgo maternal health care due to their inability to pay.

1. INTRODUCTION

The Millennium Development Goals (2000) have reiterated the need to reduce maternal mortality by 75% between 1990 and 2015. Despite significant decrease in the incidence of maternal mortality (from 409,053 in 1990 to 273,645 maternal deaths in 2011), safe motherhood still remains a distant dream for many around the world, especially in developing countries [1]. As far as India is considered, it contributed around 20% of all maternal deaths occurred worldwide in 2005 [2] and this leads many to cast serious doubts about meeting the MDG-5 within time for the country. Most of the maternal deaths are preventable if mothers have access to professional care before, during and after pregnancy [3,4]. Since the level of maternal health care utilization is still very low in India [5], it is imperative to substantially increase the use of maternal health care especially among poor in order to reduce maternal mortality and improve maternal health.

The state of government health services in India is marked by unavailability and absenteeism of health professions, poor health facility infrastructure, shortage of drugs and equipment, physical inaccessibility and callous behavior of health care professionals [6-8]. On the other hand, private sector is characterized by high user fees and high costs of medical expenditure. The cost of health services and the household’s ability to pay for health services could influence the utilization of maternity services [9]. Many studies have explored the issue of the cost of maternal health care in the past [10-14]. However, these studies have calculated maternal health care expenditure without any reference to total household expenditure. This could lead some to believe that small maternal health care expenditure is not a problem or huge expenditure is a cause of concern. A small cost of maternal health care does not necessarily mean that it does not cause impoverishment. Similarly, a high cost of health care expenditure also does not always necessarily mean that it reduces the standard of living of the household. In fact, even a small expenditure could plunge the household into poverty, if the household has no capacity to pay for health care. Contrary to that, a large expenditure may or may not force a family into poverty that has ability to pay for health care. So, the question here is how large the maternal health expenditure needs to be to force a household to a state where they decide either to forgo maternal health care or sacrifice consumption of other goods (including basic needs sometimes). Such levels of health care expenditure are generally referred to as “catastrophic” [15].

No definite answer can be found in previous studies as to what level of expenditure could be “catastrophic” for a household. In most of the recent studies, it has been arbitrarily taken as 40% of food expenditure or 10% of total household expenditure or income [16-18]. Poor households generally have very little to spend on health care because most of the household resources are absorbed by items related to basic needs, such as food. This catastrophic expenditure has been shown to have effects on poverty levels in many other countries [19-22].

Urban and rural areas are fundamentally very different from each other in many respects. Urban areas are generally characterized by higher income level, better and accessible health infrastructure. The health seeking behavior of mothers living in urban areas is also found to be very different compared to that of rural mothers [23]. There is only one national level quantitative study available on the issue of catastrophic maternal health care expenditure in India [14], To our knowledge, as yet, no study has attempted to study catastrophic maternal health care expenditure and poverty induced by it separately for urban and rural areas.

Keeping in mind the gaps left by research carried out in the past, this study aims to investigate the incidence, intensity and socio-economic correlates of “catastrophic” maternal health care expenditure. It also measures the effect of maternal health care expenditure on poverty incidence and examines the factors associated with this impoverishment due to maternal health care payments. The analyses are conducted separately for urban and rural areas. The concepts and operational definitions of the indicators for incidence and intensity of catastrophic maternal care expenditure and impoverishment due to maternal care expenditure are given in detail in next section.

2. DATA AND METHODS

The study uses data from 60th round (January-June 2004) of the National Sample Survey (NSS) which is a nationally representative survey conducted in India (excluding a few far-off and inaccessible places) aimed at collecting socio-economic data employing scientific sampling methods. Each round of the survey collects data on a particular theme. The survey adopts a stratified twostage design with sampling of census villages in the rural areas (Panchayat wards in case of Kerala) and the NSS urban frame survey (UFS) blocks in the urban areas in the first stage, followed by sampling of households in the second stage [24].

The survey collected information on consumer expenditure in 30 days before survey from 73,868 households using a set of five questions on consumption aggregates, rather than through a detailed listing of consumption items. The five items used for calculating the household consumption expenditure were 1) purchases 2) homeproduced stock 3) receipts from exchange of goods and services 4) gifts and loans and, 5) free collection. The data on total maternal health care expenditure [antenatal care (ANC), delivery care and postnatal care (PNC)] was collected for all ever-married women aged 15 - 49 years pregnant during the 365 days before the survey. Aggregate expenditures incurred by type of services (ANC, delivery and PNC) and the source of care (government or private health facility or home) were also investigated. No information was elicited on expenditure for abortion care. In all, 9660 (6533 in rural and 3127 in urban) women reported that they were pregnant during 365 days before the survey.

3. MEASUREMENT OF VARIABLES

3.1. Measuring Incidence and Intensity of Catastrophic Maternal Health Care Expenditure

Catastrophic expenditure is defined as that level of out-of-pocket (OOP) health expenditure which exceeds some fixed proportion of household income or household’s capacity to pay. The “capacity to pay” is the total annual household consumption expenditure net of subsistence expenditure on food and other basic needs. The “capacity to pay” of the household, in this study, has been derived by subtracting household poverty-line expenditure separately for rural and urban adjusted to household size from household consumption expenditure [14]. Since, NSS does not differentiate between food and nonfood items in the 60th round survey, taking poverty line as subsistence expenditure is the best way to measure the capacity to pay. The inflation adjusted data on national (India) poverty line for the year 2004-2005, as provided by the Planning Commission of India, was multiplied by household size to calculate the capacity to pay. The “capacity to pay” was adjusted to zero for households below poverty line. In this study, a household suffers catastrophic expenditure, only if total maternal health care expenditure is more than 40% of “capacity to pay”.

3.1.1. Catastrophic Head Count

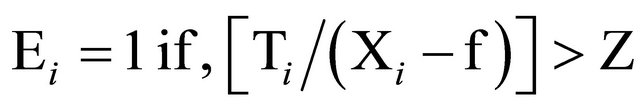

The catastrophic head count measures the incidence of catastrophic expenditure. It is the proportion of households whose maternal health care expenditure is more than 40% of their annual capacity to pay. Such households are coded as “1” and if total maternal health care expenditure is equal to less than 40%, household was coded as “0”. If “Ti” represents total OOP maternal health care expenditure, “Xi” is the total annual per capita consumption expenditure of the ith household and “f” represents the annual per capita poverty line expenditure, then “capacity to pay” of the household can be written as (Xi − f). If total household expenditure of a household is less than poverty line expenditure, the “capacity to pay” is treated as “0”. The cut-off based on proportion of the “capacity to pay” of the household could be denoted by Z cat. In this case, it is taken as 0.4. Now, let  cat, and = 0 otherwise. Then, the catastrophic head count is ∑Ei, where sum is over all the households N. Thus, the catastrophic head count ratio now is

cat, and = 0 otherwise. Then, the catastrophic head count is ∑Ei, where sum is over all the households N. Thus, the catastrophic head count ratio now is  [25].

[25].

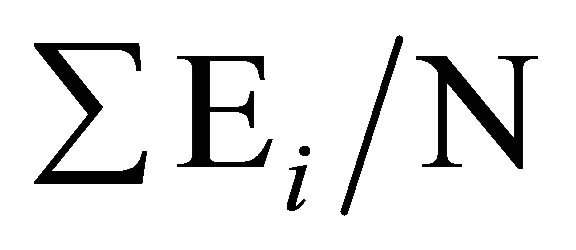

3.1.2. Mean Catastrophic Overshoot

This measure captures the depth or intensity of catastrophic payments i.e. the amount by which the maternal health care expenditure exceeds the threshold (in our case, 40% of annual capacity to pay). The mean catastrophic overshoot “Oi” is given by

3.2. Measuring Impoverishment Due to Maternal Health Care Payments

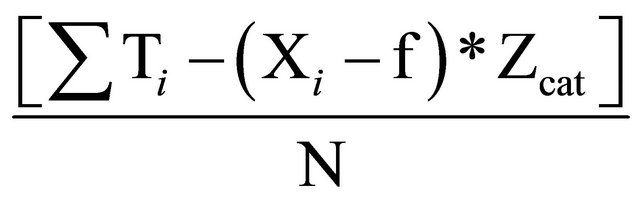

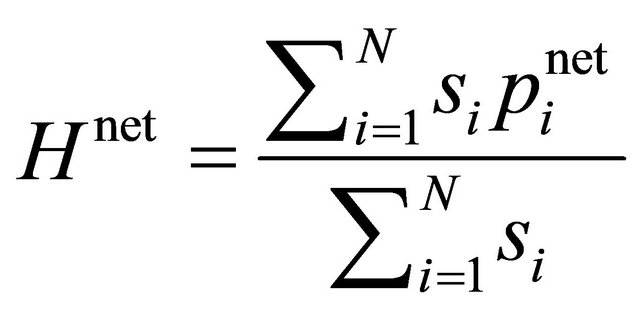

Impoverishment due to maternal health expenditure is computed by treating the households which fall below poverty line after paying for maternal health care. Using household expenditure gross of OOP payments for maternal health care, the poverty head count is Hgross. If OOP payments are subtracted from household expenditure before poverty is assessed, then the head count rises to Hnet.

Following O’ Donnell et al. (2008), pre and post maternal health care poverty head count ratios can be written in the following manner. If xi is the total con-sumption expenditure of household i, then (the gross of maternal health care payments) poverty head count ratio is:

where,  , if xi < PL and is 0 otherwise, where si is the household size. N is the number of households in the sample, and PL is the poverty line.

, if xi < PL and is 0 otherwise, where si is the household size. N is the number of households in the sample, and PL is the poverty line.

The net of health payments i.e. post payment poverty headcount is obtained by replacing pigross with pinet = 1, if (xi − Ti) < PL or 0 otherwise, where Ti is total maternal health care expenditure [25].

3.3. Logistic Regression

To examine the effects of various socio-economic correlates of the catastrophic maternal care expenditure and poverty induced by it, we use binary logistic regression analysis. The first dependent variable in the analysis is “catastrophic maternal health care expenditure” coded as “0” for non-catastrophic expenditure and “1” for catastrophic expenditure. The second dependent variable is “impoverishment due to maternal health care spending”. It is coded as “0” for non-impoverishment and “1” for impoverishment. The independent variables included in the analysis are religion, social group, educational attainment of women, the age of women, monthly per capita consumption expenditure (MPCE) quintiles, and household’s principal occupation.

4. RESULTS

Using data from 60th round of National Sample Survey, we first calculated the incidence and intensity of the catastrophic maternal health care expenditure and its impoverishment effect on the households. We also made an attempt to examine the factors associated with the incidence of impoverishment due to maternal health care expenditure.

4.1. Incidence and Intensity of Catastrophic Maternal Health Care Expenditure

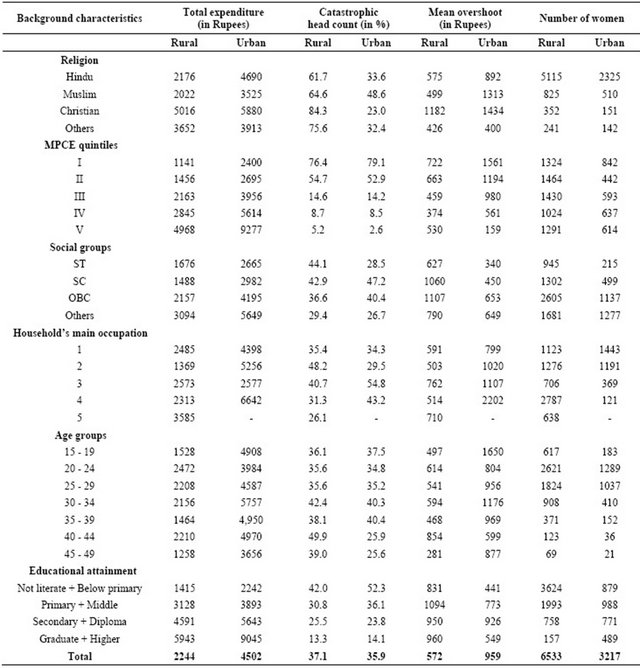

Table 1 presents the estimates of catastrophic head count—a measure of incidence of catastrophic maternal health care expenditure. It also presents the distribution of mean catastrophic overshoot—a measure of intensity of catastrophic maternal health care expenditure.

The average total expenditure was found higher in urban areas (Rs.4502) compared to rural areas (Rs.2224). As for catastrophic head count, it was slightly higher in rural areas (37%) than in urban areas (35%). Among religious groups, Muslim (49%) in urban and Christian households (84%) in rural areas suffered catastrophic expenditure more than any other religious group. More women belonging to poorer households (from lower quintiles) both in rural and urban areas were found to be

Table 1. Catastrophic head count and mean catastrophic overshoot for maternal health care expenditure by the background characteristics of women in rural and urban India, 2004.

Source: Estimated using unit-level data from 25th Schedule on Morbidity and Health Care of 60th round of National Sample Survey conducted in 2004. Note: Household’s principal occupation: Rural 1) Self-employed in non-agriculture, 2) Agricultural labor, 3) Other labor, 4) Self-employed in agriculture, 5) Others; Urban: 1) Self-employed, 2) Regular wage/salary earnings, 3) Casual labor, 4) Others.

disproportionately burdened by catastrophic expenditure.

The catastrophic head count of women belonging to Scheduled Castes (SC) and Other Backward Castes (OBC) in urban areas was higher than Scheduled Tribes (ST)

and caste group known as “Others”. However, it was higher among ST (44%) and SC (43%) women compared to “Others” (29%) in rural areas. With increasing educational attainments of women, the head count of catastrophic payments on maternal health care decreased substantially in both rural and urban India. Women belonging to households engaged in agricultural labor in rural areas (48%) and casual labor as main occupation in urban areas (55%) showed the highest catastrophic head count for maternal health care expenditures.

Table 1 also shows the amount of mean overshoot in rupees by background characteristics of women. The mean overshoot was greater for the women form urban households (Rs.959) than their counterparts living in rural areas (Rs.572). The depth of catastrophic expenditure was higher among women belonging to households from lower MPCE quintiles compared those belonging to higher consumption quintiles, both in rural and urban areas. The mean overshoot among women from Christian households in rural areas was highest (Rs.1182) followed by Hindus (Rs.575) and Muslims (Rs.499). The overshoot among women from Christian households was highest (Rs.1434) in urban areas as well, followed by women from Muslim households (Rs.1313).

With respect to social groups, the average overshoot was highest for women who belonged to OBCs (Rs.1107) followed by SCs (Rs.1060) in rural areas and “Others” (Rs.649) in urban areas. Illiterate women and women with less than five years of education were least affected. This pattern was same for both rural and urban areas. There was no clear pattern of overshoot across age groups of women in both rural and urban areas. The maternal health expenditure of the women from the households, whose main occupation was to work as “other labors”, overshoots their “capacity to pay” by Rs.762 in rural areas. The depth of financial burden was highest among the women belonging to the household with their main occupation catagorized as “Others” (Rs.2202) followed by “regular wage/salary earnings” (Rs.1107) in urban India.

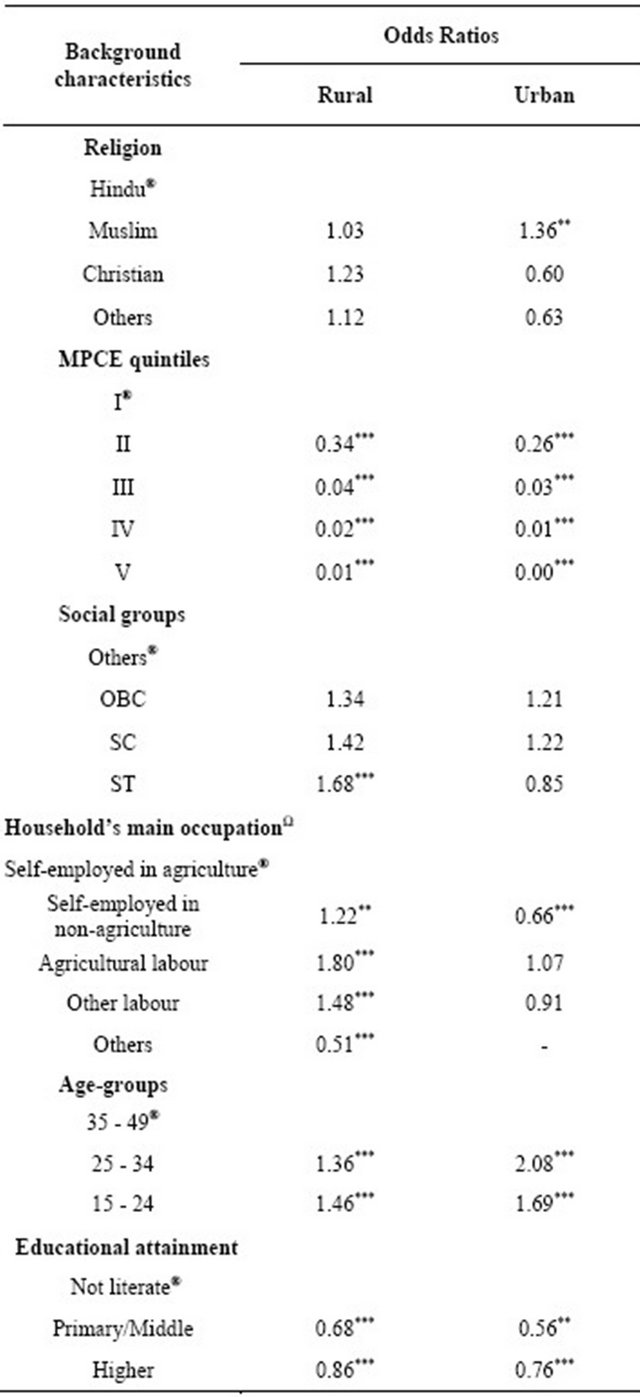

4.2. Determinants of Catastrophic Maternal Health Care Expenditure

Table 2 presents the odds ratios from two separate (one for rural areas and one for urban areas) logistic regression analyses performed to examine the effects of independent variables on catastrophic maternal health care expenditure. The MPCE of households was found to be a highly significant predictor (p ≤ 0.001) of catastrophic maternal health care expenditure. The odds of experiencing a catastrophic expenditure reduce significantly by 66%, 96%, 98% and 99% for second, third, fourth and fifth quintile compared to the first quintile in rural areas. In urban areas, the odds decrease even more sharply. The odds of catastrophic expenditure among women from the richest quintile in urban area are almost zero compared to women from the poorest quintile. While, among social groups in rural areas, the women belonging to STs were 69% more likely to witness catastrophic OOP expenditure on maternal health care compared to “Others”. In urban areas, results were in expected direction but none of them were found to be significant.

Table 2. Results of logisitc regression showing the determinants of catastrophic maternal health care payments in rural and urban India, 2004.

Note: ΩHousehold’s principal occupation: Rural: 1) Self-employed in agriculture, 2) Self-employed in non-agriculture, 3) Agricultural labor, 4) Other labor, 5) Others; Urban: 1) Self-employed, 2) Regular wage/salary earnings, 3) Casual labor, 4) others; ® = Reference category; Level of significance: ***p ≤ 0.001; **p ≤ 0.05; *p ≤ 0.01; N (Rural) = 6109; (Urban) = 2897; Pseudo R2 = 0.309 (Rural) and 0.307 (Urban).

As for religion, Muslim women in urban areas were 36% more likely to experience catastrophic maternal health care payments compared to Hindu women. The odds of catastrophic expenditure were 34% less among women belonging to the households engaged in regular wage employment in urban areas compared to women from self-employed households. However, household’s principal occupation was also found to be a significant predictor variable in rural area except for the women who belonged to households engaged in occupations categorized as “Others”. Women from household reporting their main occupation as “self-employed in non-agriculture”, “agricultural labor”, and “Other labor” showed higher odds of experiencing catastrophic payments. Similarly, with respect to the reference category of women aged 35 - 49, the women from lower age groups had significantly higher chance of incurring catastrophic payments. Rural women with middle and higher education were less likely to incur catastrophic expenditure by 31% and 13%, respectively. Similar pattern was found in urban areas too where women with middle and higher education were 43% and 24% less likely to suffer from catastrophic OOP payments.

4.3. Impoverishment Due to Maternal Health Care Expenditure

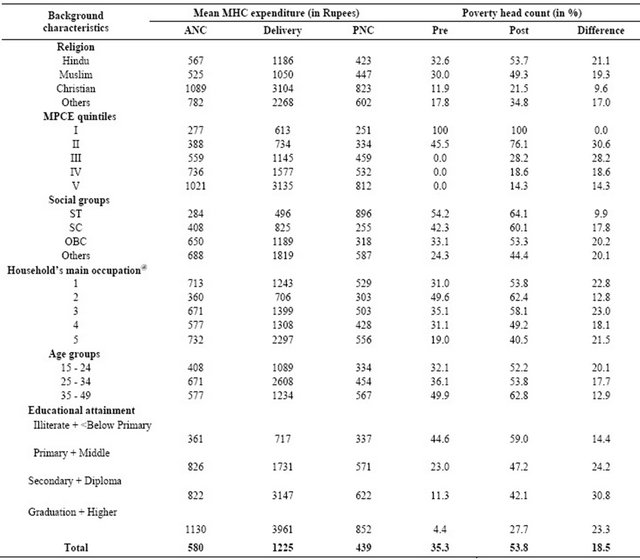

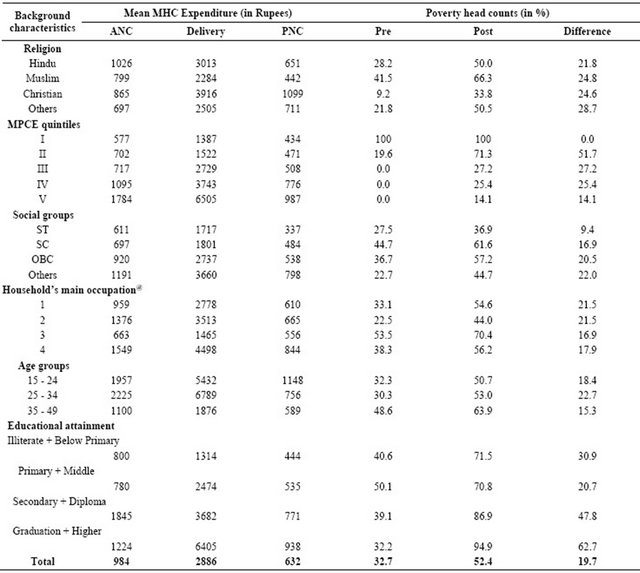

Using methods discussed above, we calculated pre and post maternal health care expenditure poverty head counts for both rural and urban areas. Tables 3 and 4 present the estimates of mean maternal health care expenditure; pre

Table 3. Maternal health care expenditure and increase in poverty head count due to maternal health care expenditure in rural areas of India, 2004.

Note: The estimated figures show gross and net maternal health care payments poverty head counts. Inflation adjusted poverty line (rural and urban) as given by Planning Commission for 2004-2005 has taken for the analysis. @Household’s main occupation: Rural 1) Self-employed in non-agriculture, 2) Agricultural labor, 3) Other labor, 4) Self-employed in agriculture, 5) Others; MHC stands for maternal health care.

Table 4. Maternal health care expenditure and increase in poverty head count due to maternal health care expenditure in urban areas of India, 2004.

Note: The estimated figures show gross and net maternal health care payments poverty head counts. Inflation adjusted poverty line (rural and urban) as given by Planning Commission for 2004-2005 has taken for the analysis; @Household’s main occupation: Urban: 1) Self-employed, 2) Regular wage/salary earnings, 3) Casual labor, 4) Other; MHC stands for maternal health care.

and post payment poverty head count for rural and urban areas respectively. The differentials in pre and post maternal health care poverty head count by background characteristics of women are being described in this section. Hindu women (21%) were most vulnerable to maternal health care induced poverty followed by Muslim women (19%) in rural India. On the other hand, the increase in poverty head count was very small among Christian women. In urban areas, women belonging to “Other” religions (mainly comprised of Sikhs, Jains, Buddhists and Zoroastrians) experienced highest increase (29%) in maternal health care expenditure induced poverty. The incidence of poverty induced by OOP payments for maternal health care was found to be highest for the second consumption expenditure quintile (31%) followed by the third quintile (28%). This pattern among consumption quintiles was similar for both rural and urban areas. Since, every household in the lowest MPCE quintile, in both rural and urban areas, was below poverty line, the pre-post difference was zero. However, the increase in poverty head count due to maternal health care expenditure (except highest quintile where the increase in poverty is equal) was more in other quintiles in urban households compared to rural households.

With respect to social groups, the increase in poverty head count was found to be highest for women belonged to households from caste group known as “Others” in both rural and urban areas. The women, who belonged to the households whose main occupation was “Other laborer”, “Other” and “Self-employed in non-agriculture” in rural areas, were found to be most vulnerable due to maternal health care spending with an increase of 23%, 23% and 22% in poverty headcount, respectively. Similarly in urban areas, women form the households that were either “self-employed” or earning “regular wages/- salary” experienced an increase (22%) in the poverty head count. Among different age groups of women, the highest increase in poverty head count due to OOP maternal health care expenditure was among women aged 15 - 24 years in rural areas (20%) and 25 - 34 years in urban areas (23%).

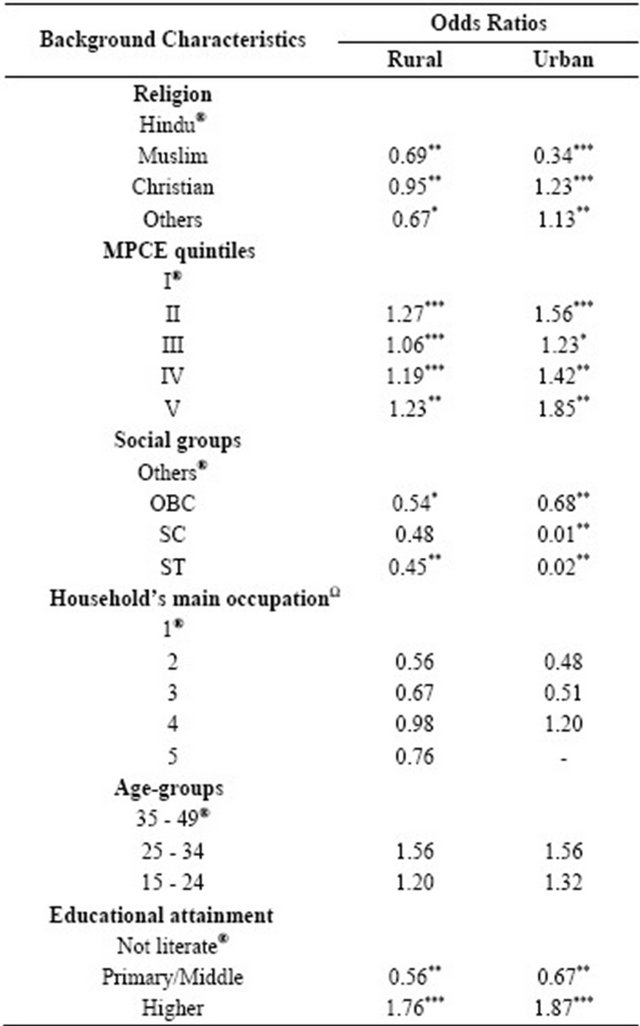

4.4. Determinants of Impoverishment Effect of Maternal Health Care Spending

Table 5 presents the odds of impoverishment due to maternal health care spending for both, rural and urban India (coded “1” for impoverishment and “0” for nonimpoverishment). The MPCE quintiles were found to be significant in both rural as well as in urban areas. The odds increase with the quintiles, for instance, the odds of being poor for the fifth MPCE quintile were 23% and 85% higher compared to the first quintile (the poorest quintile) in rural areas and urban areas, respectively.

Among social groups, the likelihood of being poor after paying for maternal health care was significantly lower by 99% and 98% for women who belonged to SCs and STs compared to women belonging to “Others” caste category in urban areas. The odds were found to be in similar direction; however, the odds were not as small as they were in urban areas. Muslims and Christians in rural areas were 31% and 5% less likely to be poor due to maternal health care expenditure.

However, in urban areas, the odds of being poor due to maternal health expenditure were 23% and 13% higher among Christians and Others, respectively than among Hindus. Interestingly, Muslims women were 66% less likely to be poor than Hindu women. It was also found that women with middle education were 44% and 33% less likely to plunge into poverty due to OOP maternal health care expenditure in rural and urban area, respectively. On the other hand, women with higher education were more likely (76% for rural and 87% for urban) to be impoverished by OOP maternal health care expenditure.

5. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Using 60th round NSS data, we estimated catastrophic head count and mean catastrophic overshoot. Secondly, we measured pre and post maternal health care expendi-

Table 5. Results of logistic regression showing the determinants of impoverishment due to maternal health care payments in rural and urban India, 2004.

Note: ΩHousehold’s Principal Occupation: Rural: 1) Self-employed in agriculture, 2) Self-employed in non-agriculture, 3) Agricultural labour, 4) Other labour, 5) Others. Urban: 1) Self-employed, 2) Regular wage/salary earnings, 3) Casual labour, 4) Others; ® = Reference category; Level of significance: ***p ≤ 0.001; **p ≤ 0.05; *p ≤ 0.01: N (Rural) = 6109; (Urban) = 2897; Pseudo R2 = 0.209 (Rural) and 0.207 (Urban).

ture poverty head count. Additionally, we also examined socio-economic factors associated with the catastrophic OOP maternal health care expenditure and poverty induced by it, separately for urban and rural areas.

Despite Government of India’s efforts to increase maternal health care utilization in government health facilities, a large chunk of urban population including urban poor goes to private sector. The poor people face the highest burden in relative terms despite the fact that they spend less in absolute terms and most of the maternal health care services in government health facilities are free of cost. The percentage share for catastrophic OOP expenditure was slightly lower for urban households than their rural counterparts. It may be due to better government health services and relatively higher income of households in urban areas. The fact that a higher proportion of socio-economically backward households suffered with catastrophic expenditure for maternal health care could be linked with their lower “capacity to pay” and greater dependency on private health sector.

Although, women from “SC” and “ST” categories generally exhibit poor outcomes in almost all socio-economic and health indicators [5], these women in our study showed decreased odds of impoverishment induced by maternal health care expenditure in both rural and urban areas compared to women from higher castes. This is also evident from pre-post difference in poverty head counts by caste. The women from “OBC” and “Other” households witnessed largest increase in poverty. These castes are considered socio-economically betteroff compared to SC and ST. It was also seen that like poorer households, many richer households too plunged into poverty due to maternal care expenditure. This indicates that neither rich nor poor can have maternal health care without affecting their well-being.

It was anticipated that the new demand side financing for maternal health care in the form of Janani Suraskha Yojana (JSY) program might help in reducing the burden of out of pocket expenditure especially for the disadvantaged section of the society. The JSY gives cash assistance (Rs.1400 and Rs.1000 respectively in rural and urban areas of low performing states and Rs.700 and Rs.600 respectively for rural and urban areas of high performing states) to all pregnant women who deliver at a public health facility [26]. However, our study shows that the out of pocket expenditure for delivery care exceeds substantially the amount currently assigned to the poor through JSY not only in urban areas but also in rural areas. Moreover, the maternal health expenditure induced poverty is also slightly higher in urban areas than in rural areas. It is worth mentioning here that the expenditure for antenatal and postnatal care also makes a substantial part of total maternal health expenditure in both rural and urban India. In the absence of any external financial cover for the costs of antenatal care and postnatal care services, it is likely that the picture of OOP maternal health expenditure induced poverty probably did not change substantially during last seven years of JSY implementation. The impact of delivery care cash transfer through JSY on maternal health care expenditure at household level is yet to be examined with a recent data. If maternal health care expenditure induced poverty is to be reduced substantially, the demand-side maternal health care financing programs and policies in future should take into consideration all types of costs incurred during prenatal, delivery and postnatal periods and focus not only on those women who suffered catastrophic expenditure and plunged into poverty but also those who forgo maternal health care due to their inability to pay.

Looking at the limited scope of the paper, it could be suggested that the future work on this issue could estimate and analyse state-wise rural-urban differentials in catastrophic expenditure for maternal health care and poverty induced by it which is even more relevant from the policy perspective of the states. Due to the limitations of NSS dataset, we could not examine some relevant variables that could possibly have an effect on catastrophic expenditure and poverty induced by it. An extensive and in-depth exploration of these factors could be a next step for further research in this area.

6. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are highly thankful to Dr. P. M. Kulkarni, Professor at Centre for the Study of Regional Development (CSRD), Jawaharlal Nehru University (India), for his guidance.

![]()

![]()

REFERENCES

- Starrs, A. (2001) Skilled attendance at delivery: A review of the evidence. The Interagency Group for Safe Motherhood, Family Care International, New York.

- Hogan, M.C., Foreman, K.J., Naghavi, M., et al. (2010) Maternal mortality for 181 countries, 1980-2008: A systematic analysis of progress towards Millennium Development Goal 5. Lancet, 375, 1609-1623. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60518-1

- World Health Organisation (WHO) (2005) The World Health Report 2005: Make every mother and child count. The World Health Organization, Geneva. http://www.who.int/whr/2005/en/

- Dhakal, S., Chapman, G.N., Simkhada, P.P., van Teijlingen, E.R., Stephens, J., et al. (2007) Utilization of postnatal care among rural women in Nepal. BMC Pregnancy and Child Health, 7, 1-9.

- International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and ORC Macro International (2007) National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3), 2005-2006. IIPS, Mumbai.

- Hussain, Z. (2011) Health of the national rural health mission. Economic & Political Weekly, 46, 53-60.

- Garg, S., Singh, R.M. and Grover, M. (2012) India’s health workforce: Current status and the way forward. The National Medical Journal of India, 25, 111-113.

- National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) (2011) Bulletin on Rural Health Statistics in India 2011. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (Statistics Division), Government of India. http://nrhm-mis.nic.in/Publications.aspx

- Mohanty, S. and Srivastava, A. (2012) Out-of-pocket expenditure on institutional delivery in India. Health Policy and Planning. doi:10.1093/heapol/czs057

- McCord, C., Premkumar, R., Arole, S. and Arole, R. (2001) Efficient and effective emergency obstetric care in a rural Indian community where most deliveries are at home. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, 75, 297-307. doi:10.1016/S0020-7292(01)00526-4

- Balaji, R., Dilip, T.R. and Duggal, R. (2003) Utilization of and expenditure on delivery care services: Some observations from Nashik District, Maharashtra. Regional Health Forum, 7, 33-41.

- Duggal, R. (2004) The political economy of abortion in India: Cost and expenditure patterns. Reproductive Health Matters, 12, 130-137. doi:10.1016/S0968-8080(04)24012-5

- Sharma, S., Smith, S., Pine, M. and Winfrey, W. (2005) Formal and informal reproductive health care user fees in Uttaranchal, India. Policy Project, Washington.

- Bonu, S., Bhusan, I., Rani, M. and Anderson, I. (2009) Incidence and correlates of catastrophic maternal health care expenditure in India. Health Policy and Planning, 24, 445-456. doi:10.1093/heapol/czp032

- Ghosh, S. (2010) Catastrophic payments and impoverishment due to out-of-pocket health spending: The effects of recent health sector reforms in India Asia Health Policy Program. Working Paper #15. http://asiahealthpolicy.stanford.edu

- Xu, K., Ravndal, F., Evans, D.B. and Carrin, C. (2009) Assessing the reliability of household expenditure data: Results of the World Health Survey. Health Policy, 91, 297-305. doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2009.01.002

- Wagstaff, A. and vanDoorslaer, E. (2003) Catastrophe and impoverishment in paying for health care: With applications to Vietnam 1993-1998. Health Economics, 12, 921- 932. doi:10.1002/hec.776

- Kawabata, K., Xu, K. and Carrin, G. (2002) Preventing impoverishment through protection against catastrophic health expenditure. The Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 80, 612.

- Limwattananon, S., Tangcharoensathie, V. and Prakongsa, P. (2007) Catastrophic and poverty impacts of health payments: Results from national household surveys in Thailand. The Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 85, 600-606. doi:10.2471/BLT.06.033720

- Mendola, M. (2007) The impoverishing effect of adverse health events: Evidences from Western Balkans. Policy Research Working Paper No 4444. The World Bank, Washington.

- Wagstaff, A. and van Doorslaer, E. (2003) Catastrophe and impoverishment in paying for health care: With applications to Vietnam 1993-98. Health Economics, 12, 921-934. doi:10.1002/hec.776

- O’Donnell, O., van Doorslaer, E., Rannan-Eliya, R., et al (2007) The incidence of public spending on health care: Comparative evidence from Asia. World Bank Economic Review, 21, 93-123. doi:10.1093/wber/lhl009

- Navaneetham, K. and Dharmalingam, A. (2000) Utilization of maternal health care services in South India, Centre for Development Studies. Trivendrum Working Papers 307, Centre for Development Studies, Trivendrum.

- National Sample Survey Organization (NSSO) (2006) Morbidity, health care and condition of the aged: NSSO 60th round (January-June 2004). Ministry of Statistics and Program Implementation, Government of India, New Delhi.

- O’Donnell, O., Van Doorslaer, E., Wagstaff, A. and Lindelow, M. (2008) Analyzing health equity using household survey data: A guide to techniques and their implementation. The World Bank, Washington.

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MOHFW) (2006) Janani Surakhsha Yojana—Features and frequently asked questions. Government of India. http://jknrhm/PDF/JSR.pdf