Health

Vol. 4 No. 11 (2012) , Article ID: 24906 , 10 pages DOI:10.4236/health.2012.411168

Asian-American elders’ health and physician use: An examination of social determinants and lifespan influences

![]()

1Silver School of Social Work, New York University, New York, USA; *Corresponding Author: duy.nguyen@nyu.edu

2Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University, New York, USA

Received 1 September 2012; revised 7 October 2012; accepted 22 October 2012

Keywords: Immigrants; Health Inequities; Ageing; Social Determinants of Health

ABSTRACT

While the Asian American population is growing rapidly, relatively little research has focused on intergroup health comparisons. The application of the life course perspective sheds new light on the inter-section of the ageing process and social determinants of health. This study compares physician use and health equity among Asian ethnic groups and non-Hispanic Whites. Data on Asian American and non-Hispanic White immigrants over 65 were extracted from the California Health Interview Survey. Weighted logistic regression models were tested applying the Commission on Social Determinants of Health model. Intergroup differences in physician use and health equity were observed. Furthermore, physician use and health varied among the groups by age. The diverse background of older Asian Americans and the differential effects of the ageing process point to the need for novel interventions to promote health among this population.

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. Background

Racial and ethnic minority groups in the United States are growing rapidly. Though often overlooked, Asian Americans are no exception to this unprecedented growth. By 2050, the Asian American population is projected to grow by 213% to 33.4 million people and will represent about 8% of the total US population [1]. Asian immigrants to the United States pose a unique public health challenge given the ethnic diversity within the Asian race and the varied experiences that shape their lives in America. Additionally, as a racial group affected by migration, Asian Americans face cultural challenges to health equity that compound the effects of social determinants of health. Despite rapid population growth, relatively little health research has focused on Asian Americans [2,3]. In order to address the needs of this growing population, further research must investigate the unique health circumstances of Asian Americans and how the considerable diversity within the population impacts health outcomes.

This study focuses on health and physician use among Asian American elders in comparison to Whites, looking at how the aging process affects social determinants of health differently. In addition to age and ethnic background, broader structural and intermediary determinants such as socioeconomic status, psychosocial, and environmental factors likely affect Asian Americans health status. Therefore, this study combines data from the 2005 and 2007 California Health Interview Survey (CHIS) to determine health disparities by ethnic group and then apply a model of social determinants of health to analyze differences.

1.2. Theoretical Framework

Many researchers have documented the relationship between social determinants and health inequities. The Commission on Social Determinants of Health (CSDH) model uses structural and intermediary determinants to explain health inequities [4]. Structural determinants include factors related to socioeconomic status and the broader social opportunity structures that determine access to health care. Social inequities, such as discrimination in the healthcare system, language barriers, and limited access to health care may contribute to higher rates of morbidity and mortality, specifically among racial and ethnic minority groups in the US Intermediary determinants of health include biological and psychosocial factors. Solar and Irwin additionally list access to health care as a major intermediary determinant that is linked with health equity [4]. Health systems are particularly important when thinking about access to care and social participation as these differ by ethnic group and age; for instance, the needs of an older immigrant population may differ from those of a mainstream audience because of various socioeconomic circumstances and cultural beliefs [5].

1.2.1. Physician Use

Receiving care from a physician is one mechanism to improve health [3]. Certainly, many older Asian Americans regularly visit physicians [6], but research with Asian American samples has identified multiple barriers to service utilization, including language difficulties, a fragmented healthcare system, lack of insurance, and lack of knowledge about existing resources [7-9].

1.2.2. Health Equity

The literature on the health of Asian Americans has focused on pan-Asian analyses as well as group-specific studies. Zahran et al. [10] found that Asians/Pacific Islanders reported better health status; fewer physical, mental, and overall unhealthy days; and fewer activity limitation days compared with non-Hispanic Caucasians, Hispanics, American Indians/Alaskan Natives, and nonHispanic African Americans. Yet for specific health conditions, such as diabetes and other chronic illnesses, Asian Americans are at increased risk of morbidity [11- 13].

Although Asian Americans are categorized as one race, there is great diversity in health outcomes among Asian ethnic groups [14-16] in the United States. In his review of Asian health, Dhooper described the health and access-to-care challenges that Asian Americans face. Notably, the foreign-born face access-to-care barriers associated with limited English proficiency, lack of insurance, and low levels of education [17]. Not surprisingly, selfreporting of poor health has been associated with an increased incidence of chronic health conditions and disease. In Sohn’s study of older Korean adults, 69% reported being in poor health, 33% lacked insurance, and 31% had not seen a physician in the past 12 months [18].

1.2.3. Purpose

The widely varying immigration experiences of diverse Asian ethnic groups continue to influence the health statuses of older adults [5]. The life course perspective may be helpful in understanding the differential impact of life experiences, historical events, transitions, and developmental trajectories across the life span of Asian Americans [19] because it posits that individual aging experiences are differentiated by sociohistorical factors, opportunity structures, and life events [20,21]. In particular, the life course perspective provides an overarching framework to explain variations in the aging process [21,22], wherein the differential experiences of particular Asian ethnic groups and the effects of aging are related to physician use and health equity.

While the literature has documented health inequities throughout the lifespan, little research has examined how the aging process differentiates health outcomes in later life among Asian Americans. To address this knowledge gap, this study applies the CSDH model to examine the health and physician utilization use of older Asian immigrants. In particular, this study seeks to address the following questions:

1) How does the health of older Asian Americans compare to that of non-Hispanic Whites?

2) To what extent are there differences in health and physician use between Asian ethnic groups and nonHispanic Whites?

3) What are the joint effects between age and ethnicity on the health and physician use of older Asian American immigrants?

2. METHODS

2.1. Data Collection

This study used publicly available data derived from the 2005 and 2007 versions of the California Health Interview Survey (CHIS). Conducted by the Center for Health Policy Research at UCLA, the CHIS is a cross-sectional study of California residents’ health and access to care. The CHIS is a random-digit-dial telephone survey that uses a two-stage sampling procedure. More Asian Americans live in California than in any other state, and combining two CHIS years enables this study to have the statistical power to focus on interethnic differences among older Asian American adults. The survey instrument was translated into a number of Asian languages, including Cantonese, Mandarin, Korean, Vietnamese, and Khmer. The overall response rates were consistent with other health surveys, ranging from 27% in 2005 to 21.1% in 2007 [23,24].

2.2. Participants

For the purposes of this study, only Asian and White respondents over the age of 65 at the time of the surveys were included in the sample. Respondents who selfidentified as Asian were included in this study if they were Chinese, Filipino, Korean, or Vietnamese. A total of 1340 adults responded to the 2005 CHIS, while 2085 responded to the 2007 CHIS. The local IRB approved the protocols for this study.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Dependent Variables

General health. Respondents to the CHIS were asked: “Would you say that in general your health is excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor?” The item was used as an ordinal variable.

Physician use. One item on the CHIS was used to measure physician utilization. Respondents were asked, “How many times have you seen the doctor in the past 12 months?” The responses to the item were dichotomized such that any contact with a physician in the past 12 months was coded as “yes.”

2.3.2. Independent Variables

Race/ethnicity was used as the independent variable. The variable was categorized as Chinese, Filipino, Korean, or Vietnamese. Non-Hispanic Whites were the reference group.

2.3.3. Covariates

2.3.3.1. Structural Determinants Based on the CSDH framework, age, gender, marital status, English proficiency, and educational attainment were used as structural determinants of health. Marital status was categorized into three groups: divorced/separated/widowed and never married, with married as the reference group. English proficiency, a continuous variable in this study, was measured by a single item: “How well do you speak English?” Responses ranged from well to not well, with only English as the reference. Educational attainment (less than high school, high school graduate, and some college), insurance status, and poverty level, as defined in the CHIS, were used as economic controls. Respondents were also asked to indicate how many years they had been in the United States (less than 15 years, or 15 years or more).

2.3.3.2. Intermediary Determinants The CSDH framework conceptualizes health and psychosocial factors as intermediary determinants of health. Accordingly, diagnosis of diabetes or cardiovascular disease, and mental health distress were used as the intermediary determinants. Mental health distress was measured using the K-6 scale. The six-item inventory assesses the prevalence of negative feelings in the past 30 days by asking the following questions: 1) “How often during the past 30 days did you feel nervous—would you say all of the time, most of the time, some of the time, a little of the time, or none of the time?” 2) “During the past 30 day, about how often did you feel hopeless?” 3) “During the past 30 days, about how often did you feel restless or fidgety?” 4) “How often did you feel so depressed that nothing could cheer you up?” 5) “During the past 30 days, about how often did you feel that everything was an effort?” 6) “During the past 30 days, about how often did you feel worthless?” Responses to the six items were summed to obtain a composite score (range = 0 to 24) that was used as a covariate. The Cronbach’s coefficient alpha for the six items was 0.84.

2.4. Analyses

Univariate analyses were used to develop a basic understanding of the factors that affect health and physician use among older Asian American and non-Hispanic Whites. Additionally, bivariate analyses were used to examine associations among the variables. Separate logistic regression models were tested for physician use and overall health. All analyses applied replicate weights to account for complex sampling and were conducted using SAS 9.2 software [25].

3. RESULTS

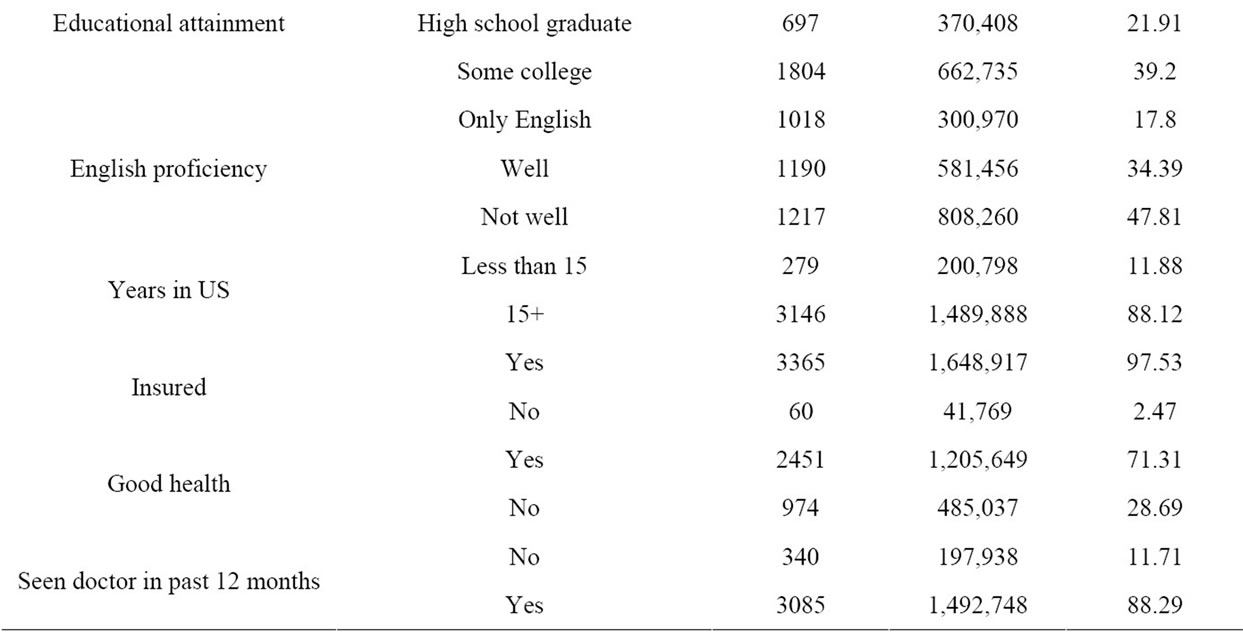

Table 1 provides an overview of the sociodemographic characteristics of the study sample. A greater percentage of the respondents were female (58%) and married (58%). Among the Asian ethnic group, Chinese respondents (16.8%) were the largest subgroup, followed by Filipinos (13%) and much smaller percentages of Korean and Vietnamese adults. Only 34% of respondents reported that they spoke English well, despite nearly 40% indicating some form of college education and a substantial 88% having lived in the United States for 15 or more years. A resounding majority of the sample indicated having health insurance (97.69%) and having seen a doctor in the last 12 months (88%). Finally, 71% of the adults in this sample self-identified as being in good health.

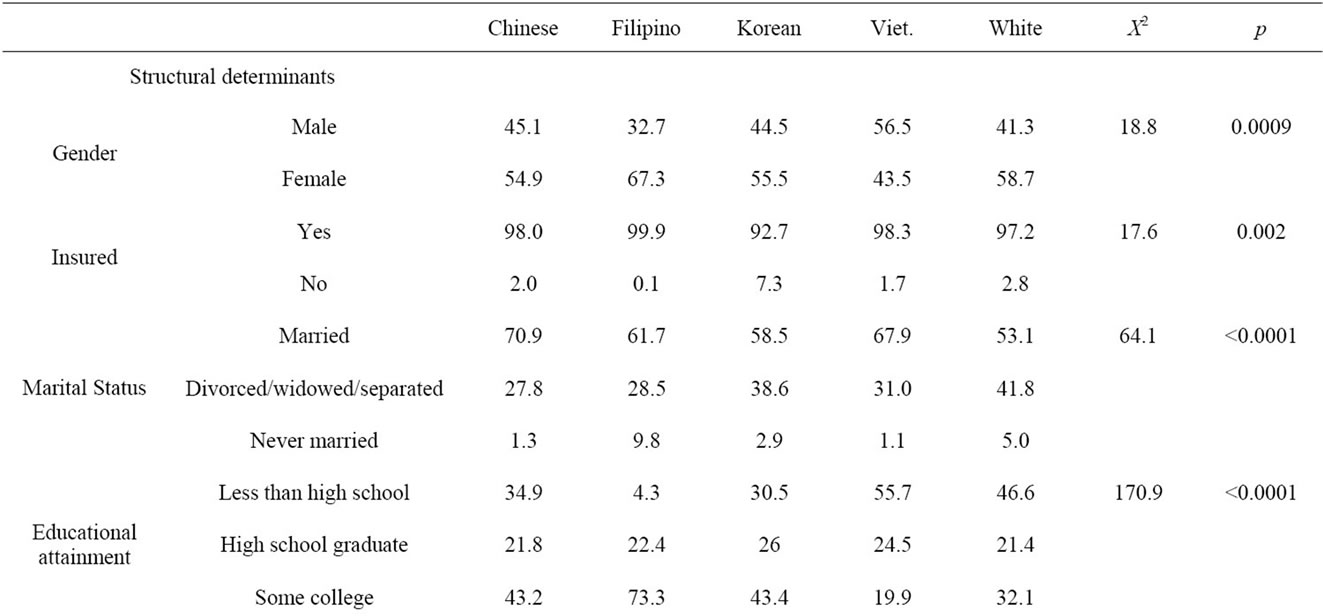

Table 2 presents descriptive statistics of the sampled adults age 65 and over by ethnic group. The distribution of gender varied across the groups. The majority of the sample was married, with the highest percentage of divorced/widowed/separated adults in the Korean (38.6%) and White (41.8%) groups. The educational attainment and English-speaking abilities across the groups are noteworthy. Among the Asian ethnic groups, 73% of Filipino elders possessed some form of college education and 82% spoke English well in addition to presumably speaking another language (only 5.8% reported knowing only English). In contrast, 43.4% of Korean respondents had some college education; however, 79.6% did not report speaking English well. Similarly, 43.2% of Chinese respondents had some college education but only 27.2% indicated that they spoke English well. Vietnamese elders, on the other hand, reported having less than a high school education (55.7%) and 86% said that they did not speak English well.

The majority of the respondents across the groups had health insurance and reported having seen a doctor in the past 12 months. Rates of diagnosed diabetes and heart disease remained low across the groups.

Table 1. Sociodemographics of sample.

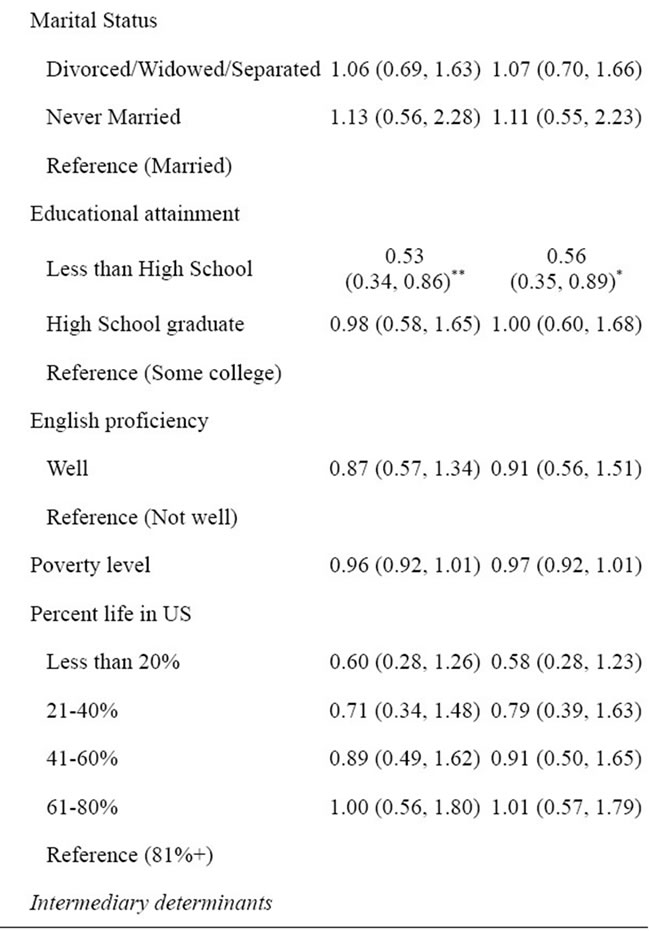

Odds Ratio for Physician Use and Good Health

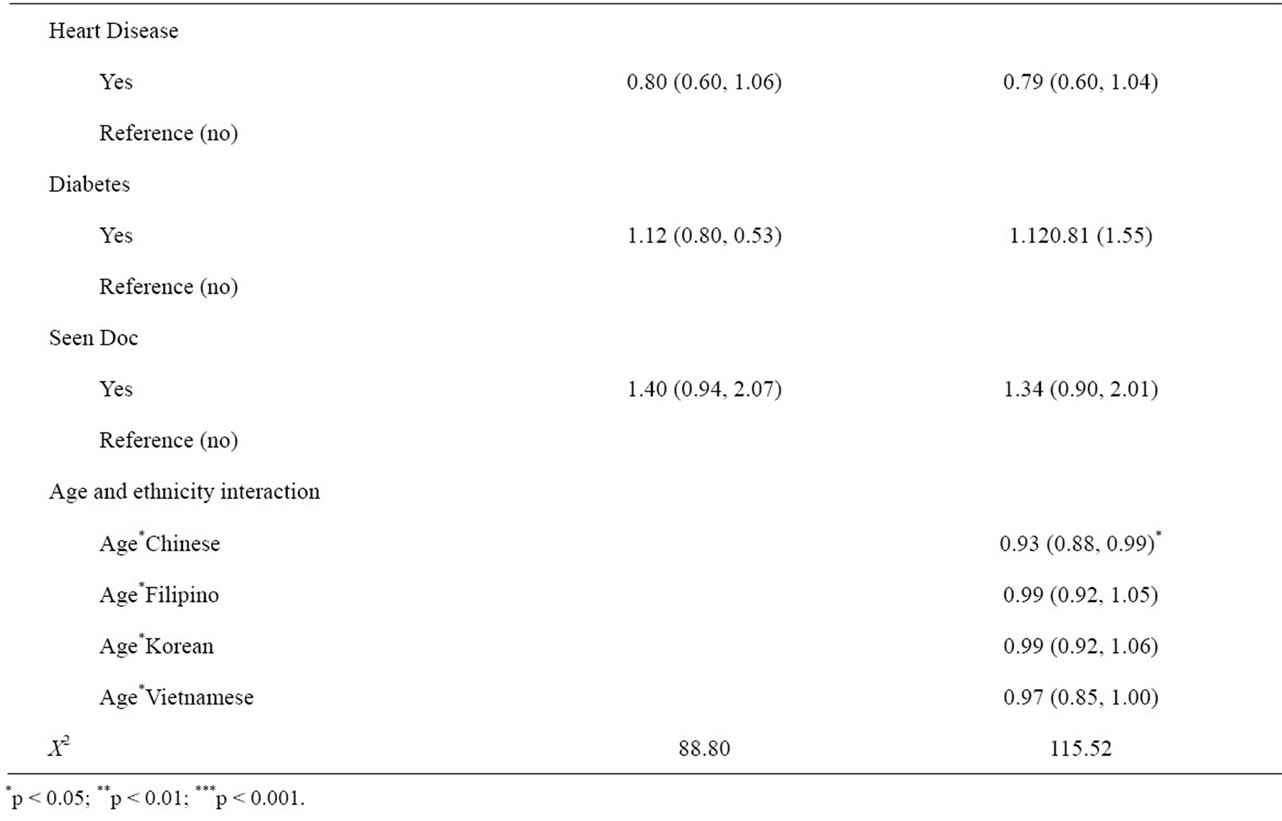

Table 3 presents the results of the separate weighted logistic regression models for physician use and overall health. First, a main effects model was tested and significant intergroup differences were found. Subsequently, the CSDH model was used to test the effects of age and ethnicity on physician use (Wald X2 = 124.19). Again,the interaction between ethnic group and age was significant, with increased age among Chinese Americans being associated with a decreased likelihood of having seen a physician in the last 12 months (OR = 0.89). One structural determinant, having health insurance, was significantly associated with physician use. Results show that having health insurance facilitated physician use (OR = 5.14).

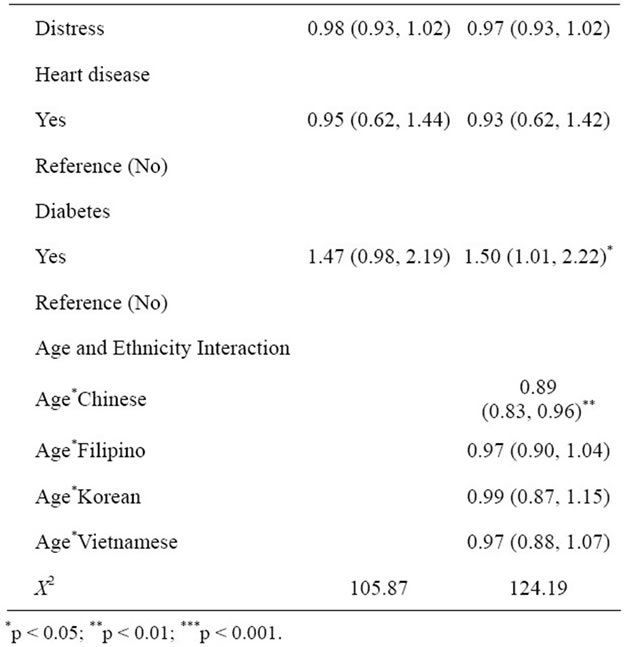

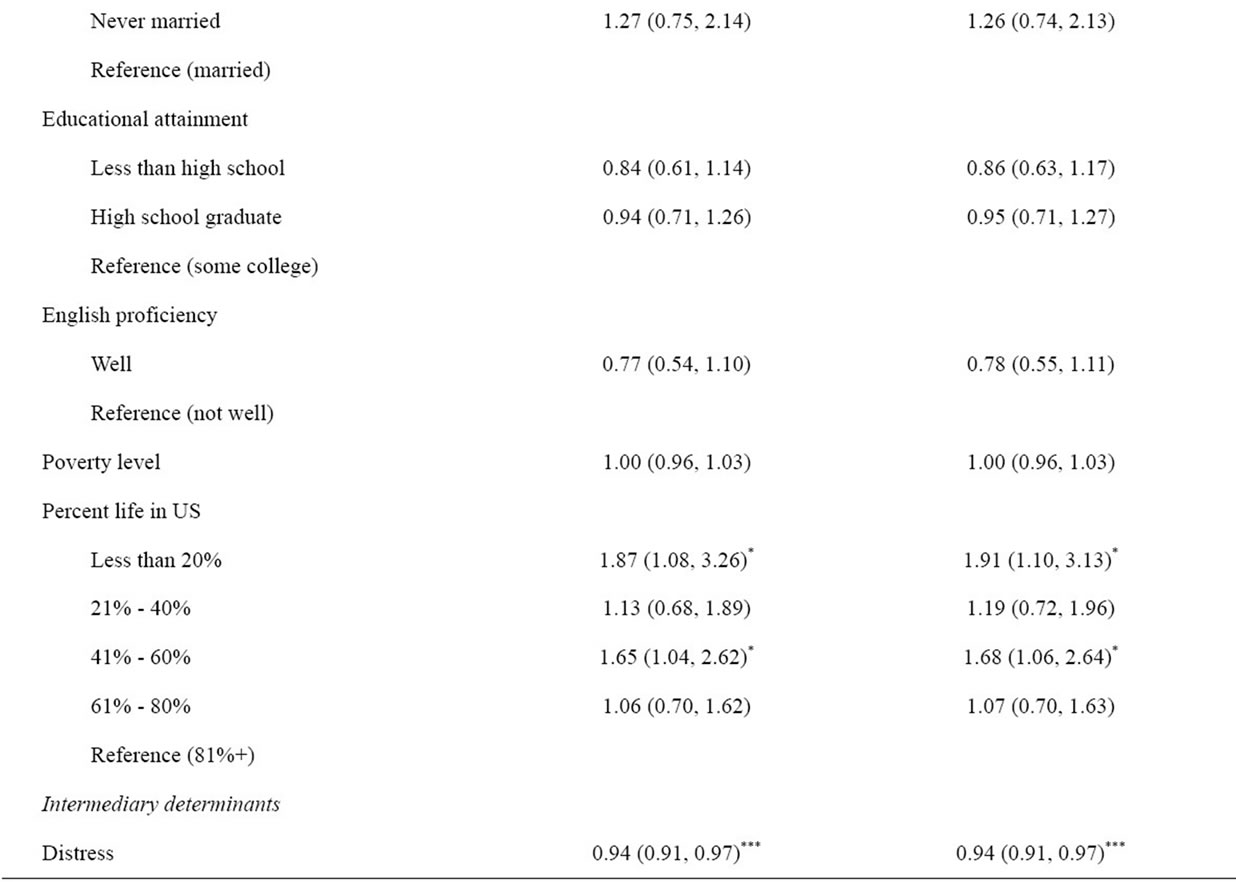

The same model was used to test the effects of intermediary and structural determinants on overall health. The results are presented in Table 4. The interaction between ethnic group and age was significant (Wald X2 = 115.52), such that increased age among Chinese American elders was associated with a decreased likelihood of reporting good health compared to non-Hispanic White elders (OR = 0.93). Increased levels of psychological

Table 2. Asian ethnic group and Whites differences.

distress, an intermediary determinant, was associated with the decreased likelihood of reporting good health (OR = 0.94). Additionally, the percentage of life spent in the United States affected overall health; immigrants who had lived in the U.S. for less than 20% of their lives (OR = 1.91) or between 41% and 60% of their lives (OR = 1.68) were more likely to be in good health than immigrants who had lived more than 80% of their lives in the US.

4. Discussion

Taken together, the results underscore the efficacy of using the CSDH model to separate social determinants of health. The results showed different patterns of physician use and good health among the various Asian ethnic groups investigated. The application of the life course perspective sheds new light on the diversity found among older Asian Americans and the differential effects of the aging process. In part, the interaction between aging and ethnicity was associated with decreased physician use.

According to the life course perspective, individual aging experiences are differentiated by sociohistorical factors, opportunity structures, and life events [20,21].

Table 3. Seen doctor odds ratios.

The life course perspective can help explain why the Chinese group as an “ethnic cohort” differs from other Asian ethnic groups [10]. With increased age, Chinese American elders are at risk for poor health as well as for having unmet health needs. The cultural beliefs of Chinese Americans—especially their perceptions of health needs and their help-seeking behaviors—warrant further exploration.

The cultural interpretations of symptoms, noted first in Kleinman’s seminal work [26], underscore the challenges of surveillance research. Each culture has its own system of health beliefs and values that carries different health-seeking behavior norms [27]. For example, researchers have pointed to the perceptions of suffering within the Confucian tradition, which fosters tolerance of suffering, as a possible explanation for some of older Chinese Americans’ health-related behaviors [14]. Kleinman posited that health care systems are made up of three arenas—the traditional, the popular, and the professional—and that a person’s health beliefs will impact which arena they look to for medical attention. Traditional medical systems tend to be the dominant health belief systems among Asians. While it is well known that many Chinese still hold cultural health beliefs, little research has been done to measure those beliefs and values among Chinese populations in Western societies [27].

The health belief system of Chinese Americans contrasts with those of other Asian ethnic groups due to life and cohort experiences that affect help-seeking behaviors. Distrust of Western medical providers and misconceptions about care can attenuate health service use among Chinese Americans. Similarly, elders with poor English

Table 4. General health odds ratios.

proficiency are more likely to use traditional medicine, as it is usually in their native language and is perceived to be less invasive than Western medicine [14]. Chung and Lin found that among Southeast Asian refugees from Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos, those with higher levels of English proficiency were more likely to use Western medical services than traditional medical care; additionally, service-use patterns varied by country of origin [28].

Vietnamese Americans, for example, have been exposed to Westernized health care through colonization, as well as through care received during the resettlement process. Prior research with Vietnamese refugees has posited that the high levels of westernized care in Vietnam have fostered physician use after resettlement [28]. Filipino elders are parts of families with an overrepresentation in the health care system. This contact with a Westernized health care system promotes health beliefs that closely mirror that of non-Hispanic Whites [29]. Additionally, due to the Philippines’ history under American administration, Filipino elders are more likely to have learned English than other Asian ethnic groups, possibly aiding their entry to the healthcare system.

The diverse background of older Asian Americans and the differential effects of the aging process point to the need for novel interventions to promote health among this population. Any such health promotion intervention must be culturally appropriate and attend to health beliefs that are grounded in traditional teachings and must be shaped by individual and social experiences. Health literacy interventions delivered through culturally appropriate media and stakeholders can reach underserved communities and bridge traditional health beliefs with evidence-based health information. Furthermore, health education materials that promote access to culturally sensitive health care providers will support access to health care among vulnerable older adults.

Limitations

The use of CHIS data presents several limitations. The CHIS was limited to California residents, which restricts generalizations of study findings to the US population as a whole. As the majority of Asian Americans live in California, this study is reflective of the experiences of most Asian Americans, yet may overlook the needs of Asians living in other parts of the United States. The survey’s low response rate may hinder accurate population estimates. The application of replicate weights, however, may mitigate some of these effects. Despite these limitations, this study is one of the few that examines the role of structural and intermediary determinants of health and health equity among Asian American ethnic groups. Furthermore, the effects of the aging process have important implications on health equity late in life.

5. NEW CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE LITERATURE

Social determinants have a profound effect on the health trajectories of minority and disadvantaged populations. The combination of the CSDH model with the life course perspective highlights the differential effects of social determinants as a function of age. The vulnerabilities of diverse racial and ethnic minority groups during the aging process underscores the need to examine the health and well-being of specific groups while considering the local context and individual and group health beliefs. Through health promotion efforts focused on specific minority communities, targeted interventions can effectively address and remedy health disparities.

6. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported in part by a grant from the Hartford Faculty Scholars program, funded by the John A. Hartford Foundation, and administered by the Gerontological Society of America.

![]()

![]()

REFERENCES

- US Census Bureau (2008) Table 17. Projections of the Asian alone population by age and sex for the United States: 2010 to 2050 (NP2008-T17), DC: Population Division, US Census Bureau. http://www.census.gov/population/www/projections/summarytables.html

- Ghosh, C. (2003) Healthy people 2010 and Asian Americans/Pacific Islanders: Defining a baseline of information. American Journal of Public Health, 93, 2093-2098. doi:10.2105/AJPH.93.12.2093

- Tanjasiri, S., Wallace, S. and Shibata, K. (1995) Picture imperfect: Hidden problems among Asian Pacific Islander elderly. Gerontologist, 35, 753-760. doi:10.1093/geront/35.6.753

- Solar O. and Irwin A. (2007) A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. Discussion Paper for the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. World Health Organization, Geneva. http://en.scientificcommons.org/23007732

- Hummer, R.A., Benjamins, M.R. and Rogers, R.G. (2004) Racial and ethnic disparities in health and mortality among the US elderly population. In: Anderson, N.B., Bulatao, R.A. and Cohen, B., Eds., Critical Perspectives on Racial and Ethnic Differences in Health in Late Life. National Academies Press, Washington DC.

- Nguyen, D., Ho, K. and Williams, J. (2011) Older Asian Americans’ primary care use: Examining the effect of perceived mental health need. Social Work in Health Care, 10, 89-103.

- Jang, Y., Kim, G., Hansen, L. and Chiriboga, D.A. (2007) Attitudes of older Korean Americans toward mental health services. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 55, 616-620. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01125.x

- Jang, M., Lee, E. and Woo, K. (1998) Income, language, and citizenship status: Factors affecting the health care access and utilization of Chinese Americans. Health and Social Work, 23, 136-145. doi:10.1093/hsw/23.2.136

- Ma, G.X. (2000) Barriers to the use of health services by Chinese Americans. Journal of Allied Health, 29, 64-70.

- Zahran, H.S., Kobau, R., Moriarty, D.G., Zack, M.M., Holt, J. and Donehoo, R. (2005) Health-related quality of life surveillance—United States, 1993-2002. MMWR Surveillance Summary, 54, 1-35.

- Misra, R., Patel, T., Kotha, P., Raji, A., Ganda, O. and Banerji, M.A., et al. (2010) Prevalence of diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular risk factors in US Asian Indians: Results from a national study. Journal of Diabetes and Its Complications, 24, 145-153. doi:10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2009.01.003

- Oza-Frank, R., Ali, M.K., Vaccarino, V., and Narayan, K. (2009) Asian Americans: Diabetes prevalence across US and world health organization weight classifications. Diabetes Care, 32, 1644-1646. doi:10.2337/dc09-0573

- McNeely, M.J. and Boyko, E.J. (2005). Diabetes-related comorbidities in Asian Americans: Results of a national health survey. Journal of Diabetes and Its Complications, 19, 101-106. doi:10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2004.08.003

- Mui, A.C. and Shibusawa T. (2008) Asian American elders in the twenty-first century: Key indicators of wellbeing. Columbia University Press, New York.

- Kim, G., Chiriboga, D.A., Jang, Y., Lee, S., Huang, C.H. and Parmelee, P. (2010) Health status of older Asian Americans in California. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 58, 2003-2008. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03034.x

- Tran, T.V., Nguyen, D., Chan, K., & Nguyen, T.N. (2007) The association of self-rated health and life-style behaviors and among foreign-born Chinese, Korean, and Vietnamese American. Quality of Life Research.

- Dhooper, S.S. (2003) Health care needs of foreign-born Asian Americans: An overview. Health and Social Work, 28, 63-73. doi:10.1093/hsw/28.1.63

- Sohn, L. (2004) The health and health status of older Korean Americans at the 100-year anniversary of Korean immigration. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 19, 203-219. doi:10.1023/B:JCCG.0000034219.97686.69

- Mitchell, J., Mathews, H.F. and Griffin, L.W. (1997) Health and community-based service use: Differences between elderly African Americans and Whites. Res Aging, 19, 199-222. doi:10.1177/0164027597192003

- Settersten, R.A. (2006) Aging and the life course. In: Binstock, R.H., George, L.K., Cutler, S.J., Hendricks, J., Schulz, J.H., Eds., Handbook of Aging and the Social Sciences. 6th Edition, Elsevier Academic Press, Burlington, 3-19. doi:10.1016/B978-012088388-2/50004-3

- Stoller, E.P. and Gibson, R.C. (1999) Worlds of difference: Inequality in the aging experience. Pine Forge Press, Newbury Park.

- Jackson, J.S., Antonucci, T.C. and Gibson, R.C. (1995) Ethnic and cultural factors in research on aging and mental health: A life-course perspective. In: Padgett, D., Ed., Handbook on Ethnicity, Aging, and Mental Health, Greenwood Press, Westport, 22-46.

- California Health Interview Survey (2005) UCLA Center for Health Policy and Research, Los Angeles.

- California Health Interview Survey (2008) UCLA Center for Health Policy and Research, Los Angeles.

- SAS Institute (2008) Design and analysis of probability surveys course notes. SAS Education, Cary.

- Kleinman, A. (1978) Concepts and a model for the comparison of medical systems as cultural systems. Social Science & Medicine. Part B: Medical Anthropology, 12, 85-93.

- Lai, D.W.L. and Surood, S. (2009) Chinese health beliefs of older Chinese in Canada. Journal of Aging and Health, 21, 38-62.

- Chung, R.C.-Y. and Lin, K.M. (1994) Help-seeking behavior among Southeast Asian refugees. Journal of Community Psychology, 22, 109-120. doi:10.1002/1520-6629(199404)22:2<109::AID-JCOP2290220207>3.0.CO;2-V

- Brush, B.L., Sochalski, J. and Berger, A.M. (2004) Imported care: Recruiting foreign nurses to US health care facilities. Health Affairs, 23, 78-87. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.23.3.78