Journal of Modern Physics

Vol.08 No.04(2017), Article ID:75074,14 pages

10.4236/jmp.2017.84042

A Possible Alternative to the Accelerating Universe IV

Frank R. Tangherlini

P.O. Box 928211, San Diego, CA 92192, USA

Copyright © 2017 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received: February 24, 2017; Accepted: March 28, 2017; Published: March 31, 2017

ABSTRACT

This work briefly reviews and extends the author’s three previous works (2015), Journal of Modern Physics, 6, 78-87, and 1360-1370; (2016), 7, 1829- 1844 that propose as an alternative to the accelerating ΛCDM universe, the decelerating Einstein de Sitter (EdS) universe, in which dark energy is a different phase of dark matter located only in intergalactic space (IGS), and that instead of a negative pressure, it has an index of refraction , and hence a reduced speed of light c / n through it. This allows the EdS universe to expand the extra distance necessary to obtain the diminished brightness of the Type Ia supernovae. In view of the recent suggestion that the universe is not accelerating, but possibly expanding uniformly, a table is given comparing both the accelerating and uniformly expanding universes with the EdS universe supplemented by the reduced speed of light. It is shown that fitting the uniformly expanding universe leads to a smaller value of n, and hence too short an age for the EdS universe, unlike the case with fitting the accelerating universe. The main result is that the proposed reduced speed of light in the IGS predicts discordant redshifts. It is shown that the current explanation of “accidental superposition,” is most likely insufficient to explain the number of observations, and that the present proposal could make up the difference. It can be tested astronomically, as illustrated in a figure.

, and hence a reduced speed of light c / n through it. This allows the EdS universe to expand the extra distance necessary to obtain the diminished brightness of the Type Ia supernovae. In view of the recent suggestion that the universe is not accelerating, but possibly expanding uniformly, a table is given comparing both the accelerating and uniformly expanding universes with the EdS universe supplemented by the reduced speed of light. It is shown that fitting the uniformly expanding universe leads to a smaller value of n, and hence too short an age for the EdS universe, unlike the case with fitting the accelerating universe. The main result is that the proposed reduced speed of light in the IGS predicts discordant redshifts. It is shown that the current explanation of “accidental superposition,” is most likely insufficient to explain the number of observations, and that the present proposal could make up the difference. It can be tested astronomically, as illustrated in a figure.

Keywords:

Dark Energy, Speed of Light, Expansion Comparisons, Discordant Redshifts

1. Introduction

Recently the author has published three papers [1] [2] [3] that describe a possible alternative to the accelerating universe that emerged from the Type Ia supernovae (SNe Ia) studies of Riess, et al. [4] , Schmidt, et al. [5] , and Perlmutter, et al. [6] . In the proposed alternative model, the dark energy instead of having a negative pressure, has rather an index of refraction n, so that the speed of light through it is reduced to c / n. Moreover, in the model it is assumed that the dark energy is only in the intergalactic space (IGS), so that within the galaxies themselves, the speed of light is c. Since galaxies do not have sharp boundaries, there will obviously be a transitional behavior of the speed of light in the halos. In Section 2, the relation of dark energy to dark matter in the model is given, in which it is proposed that dark energy is a different phase of dark matter, rather than a different substance. Also, expressions for increased apparent magnitude and distance, derived in [1] as a function of redshift and n, are given, and briefly discussed. In Section 3, the two different approaches to determining n are described: one, based on a least squares analysis, and the other, on an assumption about the expression for n in electromagnetic theory. In Section 4, in view of the recent work of Nielsen, et al. [7] , who suggest, on the basis of a statistical analysis of a larger number of SNe Ia than were used previously, that the universe seems to be expanding uniformly, rather than accelerating, a smaller least squares value, n = 1.26,was found when fitting this model, and it was used to make a comparison with the decelerating model in Table 1 which also includes two examples of the earlier comparison of the accelerating universe with the EdS universe. It is also shown from the field equations that unphysical behavior of the energy-stress tensor is found for this model. In Section 5, some predictions of the decelerating EdS model for the age of the universe are presented, where it is also shown that the smaller value of n leads to too short an age for the EdS universe. Significantly, an astronomical test of the proposed model based on discordant galactic red shifts is proposed, since a numerical analysis indicates that the current explanation underestimates the number of cases observed. A simplified description of the test is presented in Figure 1. In Section 6, there are concluding remarks.

2. Dark Energy, Reduced Speed of Light, Dark Matter

As mentioned, dark energy in this model does not have a negative pressure, or indeed any pressure at the level of approximation used here, but instead, has an index of refraction n that reduces the speed of light through it to c / n. Because of this reduction, it obviously takes longer for light to reach the Earth from the SNe Ia than it would if the speed of light remained c. This in turn gives the decelerating, but still expanding, EdS universe the additional time needed to further expand, so as to result in there being a greater distance to the SNe Ia, and hence a greater diminution in brightness, than if light traveled with speed c. This additional distance also shows up in the verification of the ΛCDM model by Anderson, et al. [8] [9] through their determination of increased distances (angular distance DA, and luminosity distance DL, as discussed in [1] )) to the “standard ruler” of the baryon acoustic oscillations (BAO). Also, the additional distance shows up in other Large Scale Structure (LSS) studies which, for brevity, will not be examined here.

On the other hand, since the speed of light within the galaxies is taken to be c, the model effectively assumes that the speed of light reduction is only occurring within the intergalactic space (IGS), and therefore that dark energy is only in the IGS. Since it was noted by Riess, et al. [10] that for , the apparent magnitude of a supernova Ia indicated that at that epoch the universe was not accelerating, hence, in the alternative model proposed here, this can only mean that the dark energy started to appear at that epoch, and that before that time there was only dark matter in the IGS, since extra-galactic baryonic matter, cosmic microwave background radiation (CMBR), neutrinos, the Higgs field, axions, gravitational radiation, and other possible constituents of the IGS are all ignored in this preliminary model. Consequently, in this model, one is led to the idea that dark energy is another phase of dark matter, and that this phase change started to take place at the above value of z, call it z*. The cause of this phase change is attributed to the expansion cooling of the dark matter in the IGS, since in the expanding universe it is the IGS that expands, and not the galaxies themselves. Clearly, there will be a transition from the central regions of the galaxies, where the speed of light is c, to the ill-defined edges of the galaxies, with their widely varying morphologies, where the speed of light would become c/n. Also, there will be a variation of n with z, with n = 1, for

, the apparent magnitude of a supernova Ia indicated that at that epoch the universe was not accelerating, hence, in the alternative model proposed here, this can only mean that the dark energy started to appear at that epoch, and that before that time there was only dark matter in the IGS, since extra-galactic baryonic matter, cosmic microwave background radiation (CMBR), neutrinos, the Higgs field, axions, gravitational radiation, and other possible constituents of the IGS are all ignored in this preliminary model. Consequently, in this model, one is led to the idea that dark energy is another phase of dark matter, and that this phase change started to take place at the above value of z, call it z*. The cause of this phase change is attributed to the expansion cooling of the dark matter in the IGS, since in the expanding universe it is the IGS that expands, and not the galaxies themselves. Clearly, there will be a transition from the central regions of the galaxies, where the speed of light is c, to the ill-defined edges of the galaxies, with their widely varying morphologies, where the speed of light would become c/n. Also, there will be a variation of n with z, with n = 1, for , and

, and  for

for , although the transition at

, although the transition at  need not be sharp. For simplicity, it is assumed that for

need not be sharp. For simplicity, it is assumed that for ,

,  is a constant, and it is left to future work to determine

is a constant, and it is left to future work to determine , although in Section 5, the consequence of restricting the constancy of n to

, although in Section 5, the consequence of restricting the constancy of n to  to 0.6 is briefly discussed. Since no dispersion was observed, no frequency dependence for n is assumed. Under these assumptions it was shown in [1] that the increase in apparent magnitude

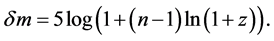

to 0.6 is briefly discussed. Since no dispersion was observed, no frequency dependence for n is assumed. Under these assumptions it was shown in [1] that the increase in apparent magnitude  is given by

is given by

(1)

(1)

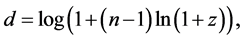

However, for some purposes, it is more convenient to convenient to work with the logarithmic measure of the fractional distance increase given by

(2)

(2)

which will be done here. The above corrections do not depend on the kind of universe that is being compared with the accelerated universe; all that is required, in addition to the independence of n on z, is that the expansion parameter satisfies

(3)

(3)

Thus, as was shown in [3] , one can carry out a comparison of the  universe with a closed universe. Also, it need not be an accelerating universe that is being compared with the EdS universe, one could have instead, a uniformly expanding universe, as suggested in [7] , that will be studied below in Section 4.

universe with a closed universe. Also, it need not be an accelerating universe that is being compared with the EdS universe, one could have instead, a uniformly expanding universe, as suggested in [7] , that will be studied below in Section 4.

3. Two Ways of Determining n

In [1] n was determined by a least squares approach, in which the difference of apparent magnitude between the  universe and the EdS universe was obtained by differencing the curves in Tonry et al. [11] , and then comparing with

universe and the EdS universe was obtained by differencing the curves in Tonry et al. [11] , and then comparing with  given in Equation (1) for

given in Equation (1) for

In [1] it was also assumed that n was not of electromagnetic origin, but it was found subsequently that there are difficulties with this assumption, and hence in [2] , upon assuming that dark energy is a medium that is linear, isotropic and non-dispersive, one is led to the following standard relation,

one has finally that

Calculations were made in [2] and [3] for various values of

In [2] it was found that for

4. Comparison of EdS with Accelerating and Uniformly Expanding Universes

Although much of the following analysis is standard, it is necessary to present it here so as to make clear the meaning of the terms in Table 1. The FLRW flat space-time line element,

Upon introducing the Hubble parameter

Since the CDM obeys the conservation law

ducing the standard definition:

Upon making use of

Now for the

Thus the above ratio becomes

For the

which has to be evaluated numerically. For the EdS universe, for

In [1] , the integral in Equation (12) was evaluated for

Under the uniform expansion scenario suggested in [7] , one has

where u is some constant speed of expansion whose value is left open, since it will drop out. Then it follows that

Where, since the universe is expanding, the positive root has been chosen. Then, from

Once again,

and hence

To compare

Table 1. In columns 2 - 5, comparison of

It will now be shown what (14) entails about the energy density and pressure for the uniformly expanding universe, from the standpoint of the field equations. Upon rewriting the line element as

and

Since for uniform expansion

5. Some Predictions of the Alternative EdS Model

Although it is clear from Table 1 that the proposed EdS model can provide an alternative to the accelerating universe to within several percent over the range

with

In contrast to the above results, based on the value of n derived from the fit to the accelerating universe, if one uses n = 1.26 that was found in fitting the uniformly expanding universe, one finds for the age of the EdS universe

Although the least squares fit yielded

In [2] there are also predictions concerning cosmic rays, but in view of space limitations, they will be omitted here, and instead, a new astronomical prediction will be discussed, that goes beyond that given in [2] , that would give a direct test of the proposed reduction of the speed of light in the IGS, and moreover, it may have already been observed, but not recognized as such. For simplicity, imagine galaxies are spheres with sharp boundaries. Then a ray of light, impinging on a galaxy from the IGS, where the speed of light is c/n, at an angle to the normal, and hence the radius of the sphere to that entry point, will be bent away from the normal, then travel through the galaxy, and upon exiting, will be bent towards the normal, and then travel to the observer that is in the plane defined by the more distant galaxy G, the point of entry R, and the center of the more nearby galaxy F Assume further that the light that came originally from G is well off to the side of F, so that G is directly observable. This situation is described in Figure 1 that is analogous to that in [2] , but in contrast, the gravitational deflection of light from G by F has been included. On the other hand, as in [2] , the refraction of the light entering our Galaxy on its way to the observer at E has been omitted. In [2] it was imagined that F and G were sufficiently nearby so that cosmological expansion could be ignored, but here it will be assumed that this is not the case. Then F will have a smaller redshift than G, and the image of G that one would see within F would provide an example of a discordant galactic redshift, a source of controversy earlier, since some investigators, particularly Arp [21] , (for a later work see Arp [22] ) mistakenly believed that discordant redshifts were an indication that greater z did not necessarily mean greater distance from the observer. Within the framework of standard Big Bang cosmology, in the absence of the herein proposed alternative model, the only admissible interpretation is that there is a galaxy behind F, but at a greater distance, and hence with a greater redshift, as shown in Figure 1 as

Figure 1. F is a lower redshift galaxy that refracts the ray RG coming from the higher redshift galaxy G, that is incident at the angle α to the radius-normal from the galactic center to R. The ray then proceeds at the refracted angle β to the other side of the galaxy at S where it is again refracted and emerges at the angle α, and goes on to the observer at E who is in the plane GRF, and who, in the standard interpretation, would assume there is a galaxy at G' that results in accidental superposition. Whereas, in the proposed model, there could be a redshift galaxy at G, albeit seen as being at G* due to the gravitational deflection of light by F, that would be the source of the higher redshift image, and could be seen directly at an angle θ* relative to the ray SE. Since galaxies are not spheres with sharp edges, the figure is obviously a highly-idealized illustration.

Thus, as a test of the proposed alternative model, since the location of the discordant redshift galaxies are known, astronomers should undertake to see whether there are any higher redshift galaxies that are suitably located off to the side of the lower redshift galaxies with the same morphology and spectral signature that could alternatively be responsible for the discordant redshift images. The failure to find any appropriate candidates, would rule out the proposed model, since the probability for this scenario would seem to be about the same as for the case when there is an actual galaxy at

In regard to this issue, Bahcall [23] made a very helpful estimate of the probable number of such accidental superpositions that suggest physical connection, as Arp [21] thought was the case. He lets

where

This smaller, but still highly uncertain, value for N suggests that about one- half of the 64 cases listed by Arp are due to something other than accidental superposition, and could instead be due to the reduced speed of light in the IGS, and the refraction scenario proposed in the highly simplified Figure 1. However, in keeping with the scientific method, only astronomical observation can settle this issue.

6. Concluding Remarks

The decelerating EdS universe, supplemented by the proposed reduction of the speed of light by the dark energy, can fit the increased distances to the SNe Ia, and hence their diminished brightness predicted by the accelerating

Cite this paper

Tangherlini, F.R. (2017) A Possible Alternative to the Accelerating Universe IV. Journal of Modern Physics, 8, 622-635. https://doi.org/10.4236/jmp.2017.84042

References

- 1. Tangherlini, F.R. (2015) Journal of Modern Physics, 6, 76-87.

- 2. Tangherlini, F.R. (2015) Journal of Modern Physics, 6, 1360-1370.

https://doi.org/10.4236/jmp.2015.69141 - 3. Tangherlini, F.R. (2016) Journal of Modern Physics, 7, 1829-1844.

https://doi.org/10.4236/jmp.2016.713163 - 4. Riess, A., et al. (1998) Astronomical Journal, 116, 1009-1038.

https://doi.org/10.1086/300499 - 5. Schmidt, B., et al. (1998) Astrophysical Journal, 507, 45-63.

https://doi.org/10.1086/306308 - 6. Perlmutter, S., et al. (1999) Astrophysical Journal, 517, 565-586.

- 7. Nielsen, J.T., Guffanti, A. and Sarkar, S. (2016) Scientific Reports, 6, Article ID: 35596.

- 8. Anderson, L., et al. (2012) Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 427, 3435-3457.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2966.2012.22066.x - 9. Anderson, L., et al. (2014) Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 439, 83-101.

https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/stt2206 - 10. Riess, A.G., Nugent, P.E., Gilliland, R.L., Schmidt, B.P., Tonry, J., Aguilar, J.A., et al. (2001) Astrophysical Journal, 560, 49-71.

https://doi.org/10.1086/322348 - 11. Tonry, J.L., et al. (2003) Astrophysical Journal, 594, 1-24.

https://doi.org/10.1086/376865 - 12. Abe, P.A.R., et al. (2015) Planck Collaboration: Astronomy and Astrophysics, 584, 1-67.

- 13. Shadab, A., et al. (2016) Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 000, 1-38.

- 14. Verde, L., et al. (2002) Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 335, 432-440.

https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-8711.2002.05620.x - 15. Hawkins, E., et al. (2003) Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 346, 78-96.

https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2966.2003.07063.x - 16. Cheng, C. and Huang, Q. (2015) Science China Physics, Mechanics and Astronomy, 58, Article ID: 599801.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11433-015-5684-5 - 17. Riess, A.G., et al. (2016) Astrophysical Journal, in Press, 1-63.

- 18. Bond, H.E., Nelan, E.P., VandenBerg, D.A., Schaefer, G.H. and Harmer, D. (2013) Astrophysical Journal Letters, 765, L12.

- 19. Gratton, R.G., et al. (2003) Astronomy and Astrophysics, 408, 529-546.

https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361:20031003 - 20. Krauss, L.M. and Chaboyer, B. (2003) Science, 299, 65-69.

https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1075631 - 21. Arp, H. (1966) Astrophysics Journal, Supplement, 14, 1-20.

https://doi.org/10.1086/190147 - 22. Arp, H. (2003) Catalogue of Discordant Redshift Associations. C. Roy Keys Inc., Montreal.

- 23. Bahcall, J.N. (1976) Redshifts as Distance Indicators. In: Field, G.B., Bahcall, J.N. and Arp, H., Eds., The Redshift Controversy, W. A. Benjamin, Inc., Reading, 61-121.

- 24. De Vaucouleurs, G. and de Vaucouleurs, A. (1964) Reference Catalogue of Bright Galaxies. University of Texas Press, Austin.

- 25. Shane, C.D. and Wirtanen, C.A. (1967) Publications of the Lick Observatory. Vol. 22, Part 1.