American Journal of Plant Sciences

Vol.4 No.6(2013), Article ID:33555,5 pages DOI:10.4236/ajps.2013.46156

Artemisia vulgaris L. Chemotypes

![]()

1Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, Mercyhurst University, Erie, USA; 2Department of Biology, Penn State Erie, The Behrend College, Erie, USA.

Email: jwilliams@mercyhurst.edu

Copyright © 2013 Jack D. Williams et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received April 1st, 2013; revised May 2nd, 2013; accepted June 1st, 2013

Keywords: Artemisia vulgaris L.; Chemotype; Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry; DNA Barcode; Solid Phase Microextraction

ABSTRACT

Artemisia vulgaris L. was collected from various regions in the USA and Montreal Canada. Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry was used to identify the analytes present in the volatiles extracted by headspace solid-phase microextraction of the crushed leaves and flowers. Four distinct chemotypes are were found: One featuring the coexistence of ar-curcumene and α-zingiberene; two marked by the presence or absence of thujone and santolinatriene; and a fourth characterized by the presence of crysanthenyl acetate (40%). DNA was used to confirm the identity of Artemisia vulgaris L.

1. Introduction

Chemotypes are chemically characterized parts of a population of morphologically indistinguishable individuals [1]. They are often defined by the most abundant chemical or chemicals produced by a plant species [1]. Examples include Origanum vulgare L. [2]; Thymus pulegioides L. [3]; Seriphidium kurramense [4]; and Artemisia judaica L. [5]. In fact based on chemical composition at least nine different chemotypes have been recognized for Artemisia absinthium [6,7]. The existence of multiple chemotypes of Artemisia vulgaris L. however, seems to have escaped attention [8,9].

The present study reports the existence of four chemotypes of Artemisia vulgaris L. based on the composition of plant volatiles.

The identity of Artemisia vulgaris L. can be confirmed morphologically [10], however identification is difficult if only parts of a plant are available for classification. Recent advances in DNA sequencing have resulted in the ability to assign species identity even if only small amounts of tissue are used.

In this study we utilize DNA barcoding for the genes matK and rbcL [11,12], linking molecular species identity with chemotyping of essential oils.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

Leaves of Artemisia vulgaris L. were collected from June of 2011 through October 2012 from various locations in North Eastern Pennsylvania; Woodbridge New Jersey; Wilmington, Delaware and Montreal Canada. The plants were identified using DNA sequencing and morphological characteristics as follows.

DNA was isolated from fresh leaf tissue using a PowerPlant DNA Isolation Kit and the manufacturer’s recommended procedure (www.mobio.com). DNA was quantified using a spectrophotometer and stored at -20oC until amplification. Using primers the regions of the genome encoding for matK and rbcL were amplified in a PCR reaction containing 100 ng of total plant DNA. The procedure outlined was based on the DNA barcode of land plants established by the CBOL Plant Working Group [13]. The quality of PCR amplification products was established using agarose electrophoresis. Amplicons were sequenced in both directions using a Sanger procedure at the Penn State Nucleic Acid Facility using the amplification primers. Consensus sequences were examined using blastn analysis against the Genbank nr database. The DNA sequences for both matK and rbcL were identical between specimens collected at all locations. Voucher sequences were deposited in the GenBank database for matK (accession KC870883) and rbcL (accession KC870884). All chemotypes analyzed were identical to the voucher sequences submitted to Genbank.

2.2. Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GCMS)

GCMS analysis of the plant volatiles was performed using an Agilent 7890A gas chromatograph with a 5975C mass selective detector from the same company. Volatile analyte separation was affected using two different fused silica capillary columns (Agilent Technologies). HP5- MS (30 m × 0.25 mm i.d., film thickness 0.25 µm) and DB624 (30 m × 0.25 mm i.d., film thickness 0.32 µm). Carrier Gas: Helium; Constant Flow: 1 mL/min; Injector temperature 250˚C; Temperature program: 50˚C for 3 min. 5˚C/min to 250˚C; 15 min. hold at 250˚C. Scan mode: 15 to 350 amu.

Wherever possible mass spectral data and calculated retention indexes for authentic compounds were used for comparison (National Institute of Standards and Technology Library, Scientific Instrument Services, Ringoes, NJ, 2008). Kovats retention indices were calculated relative to C8-C20 n-alkanes.

2.3. Headspace Solid Phase Microextraction (HS-SPME)

Leaves from each sample were collected, crushed and four grams introduced into 20 mL glass vials with screw caps (Gerstel, Inc. USA). Artemisia vulgaris volatiles were extracted using an MPS autosampler (Gerstel, Inc. USA) equipped with Car/DVB/PDMS 23 GA SPME fiber (Supelco, Bellefonte, PA, USA). Extraction time was set for 15.0 min at room temperature. Desorption (5.0 min), took place in the GC injection port operating in split mode (1:20) at a temperature of 250˚C. Conditions regarding the fiber choice, absorption time, and desorption time were chosen based on published data for the genus Artemisia and plant volatile analysis in general. [14-16].

2.4. Identification of Ar-Curcumene

An Agilent 7890A GC equipped with an LTM series II external oven was used for ar-curcumene analysis. A DB1 column was used for the first dimension (30 m × 0.25 mm i.d., film thickness 0.25 µm) and a CyclosilB (30 m × 0.25 mm i.d., film thickness 0.25 µm) for the 2nd dimension. The volume injected was 1.0µl (0.1% solution in methanol), with a split ratio of 1:20. ar-Curcumene was heart cut from the DB1 column to the CyclosilB column, followed by back flushing. Synthetic RScurcumene was used as a standard to confirm the identity of curcumene in Artemisia vulgaris L. Samples of Curcuma zanthorrhiza (The Herbarie at Stoney Hill Farm, Prosperity, SC 29127) and Zinger officinal (Newdirectionsaromatics, Mississauga, Canada L5T 2G9) were used to provide additional confirmation as Curcuma zanthorrhiza contains only R(-)-curcumene and Zinger officinal contains only S(+)-curcumene [17].

Mass spectra were obtained by electron ionization at 70 eV (ion source 150˚C; quad. 230˚C; transfer line 250˚C).

3. Results and Discussion

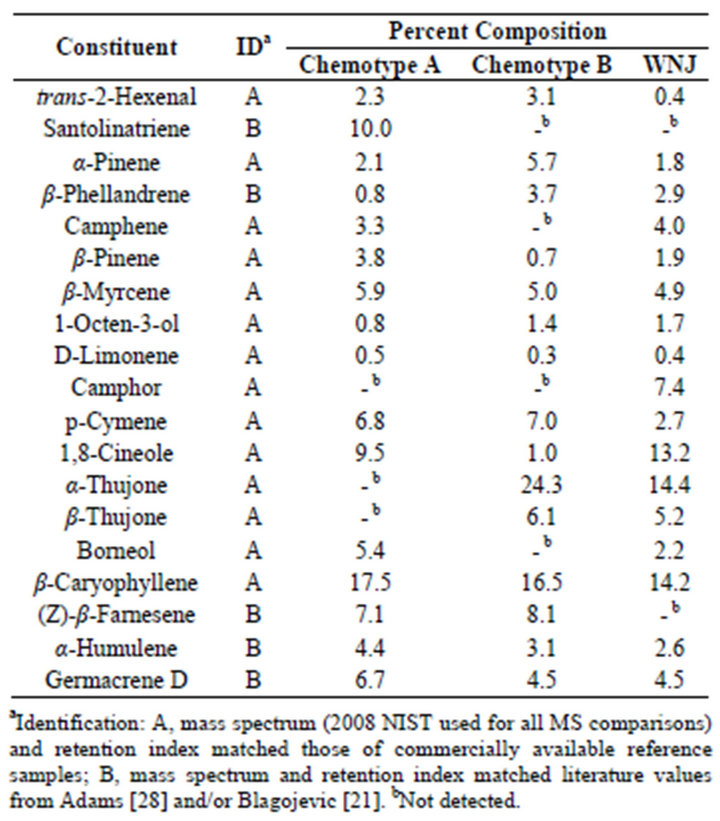

Table 1 lists the chemical composition obtained by Gas Chromatography Mass Spectrometry analysis of the volatiles from fresh leaves, of Artemisia vulgaris L. harvested from Wilmington, Delaware USA, in July of 2012. Quantitative data were obtained from total ion current (TIC) area percentages without the use of internal standards. This method has been used previously to quantify the compositions of essential oils [18,19]. Samples were collected from two populations of the plant growing in the same area, but separated by a distance of only a few meters, ensuring identical geographical and environmental influence. As can be seen in Table 1 there are some major differences between these two chemotypes (Chemotype A and Chemotype B) most significantly with respect to santolinatriene, and thujone. Samples of Artemisia vulgaris L. collected from Woodbridge New Jersey in September of 2011 provided another source for chemotype B.

Table 1. Essential oil composition of Artemisia vulgaris L. from Wilmington Delaware and Woodbridge N.J. (WNJ).

It is possible that the chemotpe B may also be found outside of the USA, although not ascribed as such. For example the thujone content of Artemisia vulgaris oil from Montpellier Cedex, France was reported as 40% [20]; Serbia, 13.5% [21]; Nilgiri Hills and Lucknow India 56% [22] and 11% [23] respectively.

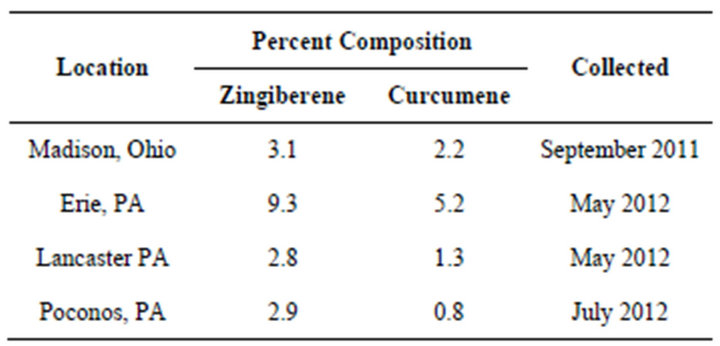

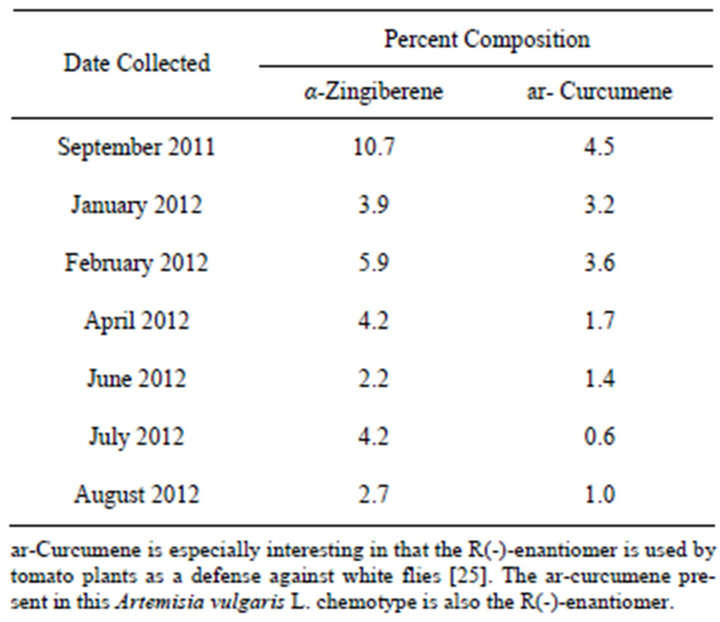

Another example of an Artemisia vulgaris L. chemotype is characterized by the presence of varying amounts of α-zingiberene and ar-curcumene. The presence of these analytes in Artemisia vulgaris L. has been previously reported, however the possibility of a chemotype was not addressed [24]. This chemotype is not confined to plants from a specific location as can be seen from Table 2. Their concentrations were however influenced by time of harvest as shown in Table 3. The analytes, characterizing this chemotype, have not been reported for regions outside of the USA. ar-Curcumene is especially interesting in that the R(-)-enantiomer is used by tomato plants as a defense against white flies [25,26]. The arcurcumene present in this Artemisia vulgaris L. chemotype is also the R(-)-enantiomer.

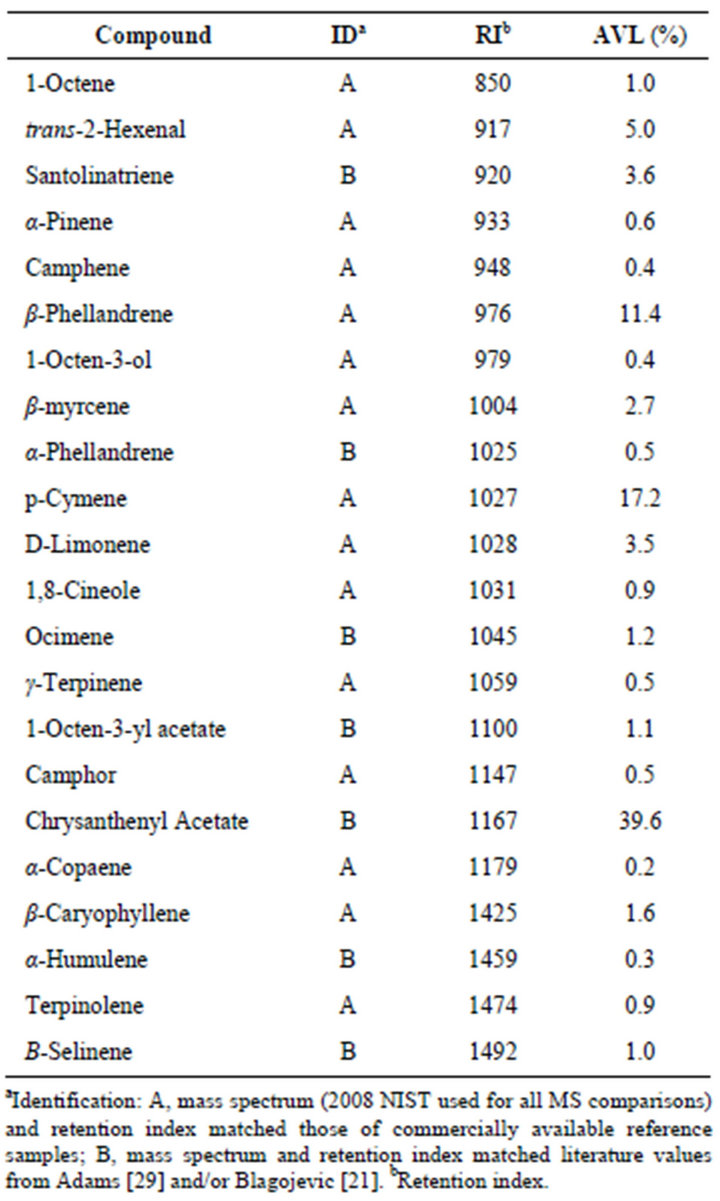

Table 4 lists the concentrations of analytes characterizing Artemisia vulgaris leaves originating from Mont

Table 2. α-Zingiberene, ar-Curcumene (GC-MS).

Table 3. Seasonal variations in curcumene/zingiberene concentrations from the aerial parts of Artemisia vulgaris L. growing wild in Erie PA.

Table 4. Essential oil composition of Artemisia vulgaris L. from Montreal Canada.

real, Canada and provides an example of a chrysanthenyl acetate chemotype. A total of 22 analytes accounted for 94.1% of the essential oil composition. Chrysanthenyl acetate, along with the alcohol chrysanthenol has been reported previously in samples of Artemisia vulgaris L. from Siauliai, North Lithuania [27] and as the alcohol in samples from Croatia [28]. We suspect that these represent the same chemotype as that from Montreal. The alcohol originates from hydrolysis of the ester during hydrodistillation [27].

4. Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Professor James Vyvyan, Western Washington University, Bellingham, WA for providing us with synthetic samples of R/S-curcumene.

REFERENCES

- K. Keefover-Ring, J. D. Thonpson and Y. B. Linhart, “Beyond Six Scents: Defining a Seventh Thymus vulgaris Chemotype New to Southern France by Ethanol Extraction,” Flavour and Fragrance Journal, Vol. 24 No. 3, 2009, pp. 117-122. doi:10.1002/ffj.1921

- L. De Martino, V. De Feo, C. Formisano, E. Mignola and F. Senatore, “Chemical Composition and Antimicrobial Activity of the Essential Oils from Three Chemotypes of Origanum vulgare L. ssp. Hirtum (Link) Ietswaart Growing Wild in Campania (Southern Italy),” Molecules, Vol. 14, No. 8, 2009, pp. 2735-2746. doi:10.3390/molecules14082735

- E. Groendahl and B. K. Ehlers, “A New Cis-Sabinene Hydrate Chemotype Detected in Large Thyme (Thymus pulegioides L.) Growing Wild in Denmark,” Journal of Essential Oil Research, Vol. 20, No. 1, 2008, pp. 40-41. doi:10.1080/10412905.2008.9699417

- S. A. Gilani, Y. Fujii, M. Sugano and K. N. Watanabe, “Chemotypic Variations and Phytotoxic Studies of Essential Oils of Endemic Medicinal Plant, Seriphidium kurramense, from Pakistan,” Journal of Medicinal Plants Research, Vol. 4, No. 4, 2010, pp. 309-315.

- E. Putievsky, U. Ravid, N. Dudai, I. Katzir, D. Carmeli and A. Eshel, “Variations in the Essential Oil of Artemisia judaica L. Chemotypes Related to Phenological and Environmental Factors,” Flavour and Fragrance Journal, Vol. 7, No. 5, 1992, pp. 253-257. |doi:10.1002/ffj.2730070504

- F. S. Sharopov, V. A. Sulaimonova and W. N. Setzer, “Composition of the Essential Oil of Artemisia absinthium L. from Tajikistan,” Records of Natural Products, Vol. 6, No. 2, 2012, pp. 127-134.

- A. Orav, A. Raal, E. Arak, M. Müürisepp and T. Kailas, “Composition of the Essential Oil of Artemisia absinthium L. of Different Geographical Origin,” Proceedings of the Estonian Academy of Sciences, Chemistry, Vol. 55, No. 3, 2006, pp. 155-165.

- J. D. Williams, T. Xie and D. N. Acharya, “Headspace Solid-Phase Microextraction (HS-SPME) Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) Analysis of the Essential Oils from the Aerial Parts of Artemisa vulgaris L. Reveal the Possible Existence of New Chemotypes,” Proceedings of the 244th American Chemical Society National Meeting, Philadelphia, 19-22 August 2012, p. 204.

- J. D. Williams, “Artemisia vulgaris L.—Influence of Geographical Origin, Harvest Time and Chemotypes on 1,8- Cineole Concentration,” The International Journal of Professional Holistic Aromatherapy, Vol. 1, No. 3, 2012, pp. 11-14.

- K. F. El-Sahhar, R. M. Nassar and H. M. Farag, “Morphological and Anatomical Studies of Artemisia vulgaris L. (Asteraceae) I. Morphological Characteristics,” Journal of American Science, Vol. 6, No. 9, 2010, pp. 806-814.

- The Plant Working Group, 2013. http://www.barcoding.si.edu/plant_working_group.html

- M. W. Chase, R. S. Cowan, P. M. Hollingsworth, et al., “A Proposal for a Standardised Protocol to Barcode All Land Plants,” Taxon, Vol. 56, No. 2, 2007, pp. 295-299.

- CBOL Plant Working Group, “A DNA Barcode for Land Plants,” Proceeding of the National Academy of Sciences, Philadelphia, 27 May 2009, pp. 12794-12797.

- N. Li, Y. Mao, C. Deng and X. Zhang, “Separation and Identification of Volatile Constituents in Artemisia argyi Flowers by GC-MS with SPME and Steam Distillation,” Journal of Chromatographic Science, Vol. 46, No. 5, 2008, pp. 401-405. doi:10.1093/chromsci/46.5.401

- C. Bicchi, S. Drigo and P. Rubiolo, “Influence of Fiber Coating in Headspace Solid-Phase Microextraction-Gas Chromatographic Analysis of Aromatic and Medicinal Plants,” Journal of Chromatography A, Vol. 892, No. 1-2, 2000, pp. 469-485. doi:10.1016/S0021-9673(00)00231-4

- A. Movafeghi, D. J. Djozan and S. Torbati, “Solid-Phase Microextraction of Volatile Organic Compounds Released from Leaves and Flowers of Artemisia fragrans, Followed by GC and GC/MS Analysis,” Natural Product Research, Vol. 24, No. 13, 2010, pp. 1235-1242. doi:10.1080/14786410903108951

- W. A. König, A. Rieck, I. Hardt and B. Gehrcke, “Enantiomeric Composition of the Chiral Constituents of Essential Oils,” Journal of High Resolution Chromatography, Vol. 17, No. 5, 1994, pp. 315-320. doi:10.1002/jhrc.1240170507

- F. Gong, Y. Fung and Y. Liang, “Determination of Volatile Components in Ginger Using Gas ChromatographyMass Spectrometry with Resolution Improved by Data Processing Techniques,” Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, Vol. 52, No. 21, 2004, pp. 6378-6383.

- T. V. Lakshmi and P. Rajalakshmi, “Identification of Phyto Components and Its Biological Activities of Aloe vera through the Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry,” International Research Journal of Pharmacy, Vol. 2, No. 5, 2011, pp. 247-249.

- A. Milhau, F. Valentin, M. Benoit, M. Mallie and J. Bastide, “In Vitro Antimalarial Activity of Eight Essential Oils,” Journal of Essential Oil Research, Vol. 9, No. 3, 1997, pp. 329-333. doi:10.1080/10412905.1997.10554252

- P. Blagojvic, N. Radulovic, R. Palic and G. Stojanovic, “Chemical Composition of the Essential Oils of Serbian Wild-Growing Artemisia absinthium L. and Artemisia vulgaris L,” Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, Vol. 54, No. 13, 2006, pp. 4780-4789. doi:10.1021/jf060123o

- L. N. Misra and S. P. Singh, “α-Thujone, The Major Component of the Essential Oil from Artemisia vulgaris Growing Wild in Nilgiri Hills,” Journal of Natural Products, Vol. 49, No. 5, 1986, p. 941. doi:10.1021/np50047a038

- F. Haider, P. D. Dwivedi, A. A. Naqvi and G.D. Bagchi, “Essential Oil Composition of Artemisia vulgaris Harvested at Different Growth Periods Under Indogangetic Plain Conditions,” Journal of Essential Oil Research, Vol. 15, No. 6, 2003, pp. 376-378. doi:10.1080/10412905.2003.9698615

- J. D. Williams, A. M. Saleh and D. N. Acharya, “Composition of the Essential Oil of Wild Growing Artemisia vulgaris L. from Erie, Pennsylvania,” Natural Product Communications, Vol. 7, No. 3, 2012, pp. 637-640.

- S. Everts, “Tomato Defense Weapons,” Chemical & Engineering News, Vol. 90, No. 1, 2012, p. 31.

- M. B. Petra, J. D. Paul, A. Kai, et al., “Tomato-Produced 7-Epizingiberene and R-Curcumene Act as Repellents to Whiteflies,” Phytochemistry, Vol. 72, No. 1, 2011, pp. 68-73. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2010.10.014

- A. Judzentiene and J. Buzelyte, “Chemical Composition of Essential Oils of Artemisia vulgaris L. (Mugwort) from North Lithuania,” Chemija, Vol. 17, No. 1, 2006, pp. 12- 15.

- W. A. König, I. Jerkovic, J. Mastelic, M. Milos, F. Juteau, V. Masotti and J. Viano, “Chemical Variability of Artemisia vulgaris L. Essential Oils Originated from the Mediterranean Area of France and Croatia,” Flavour and Fragrance Journal, Vol. 18, No. 5, 2003, pp. 436-440. doi:10.1002/ffj.1246

- P. Adams, “Identification of Essential Oil Components by Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry,” 4th Edition, Alluredbooks, Carol Stream, 2009.