Open Journal of Nursing

Vol.2 No.3(2012), Article ID:23160,4 pages DOI:10.4236/ojn.2012.23037

The development of an interdisciplinary nurse educator doctoral program: Issues for consideration and goals for success

![]()

Capstone College of Nursing, University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, USA

Email: Hmstanton@bama.ua.eduH

Received 2 May 2012; revised 1 June 2012; accepted 12 June 2012

Keywords: Doctoral Program; Nursing Education; Issues; Interdisciplinary; Nursing

ABSTRACT

The nursing shortage is exacerbated by the faculty shortage, as faculty approach retirement age and too few faculty exist to replace them. Masters-prepared nurse with limited preparation for teaching may be unable to attend traditional educational programs because of work and family commitments. Without further academic preparation, these nurses are illprepared for the faculty role. The College of Nursing partnered with the College of Education to develop a nurse educator degree program to prepare nurses for the faculty role. Blended and online courses are provided by the Colleges of Nursing. The EdD. in Instructional Leadership for Nurse Educators degree can be completed in three years of coursework followed by dissertation research.

1. INTRODUCTION

The country has not experienced a health care professional shortage similar to the current one since 1986. It is increasingly difficult to find nurses for health care agencies due to RNs leaving the profession, more RNs retiring, and lack of interest in health careers among young people.

The US Bureau of Labor Statistics noted that more than one million new and replacement nurses were needed as early as 2010 and identified Registered Nursing as the top occupation for job growth through the coming year [1]. This translates to a need for large numbers of prepared faculty to educate these new nurses.

Intensifying the nursing shortage is the increasing deficit of full-time master’s and doctorally prepared nursing faculty. Unfortunately the shortage of faculty is contributing to the current nursing shortage by limiting the number of students admitted to nursing programs. In 2010, AACN determined that 67,593 qualified applications to baccalaureate, masters and doctoral programs were not accepted; and an insufficient number of faculties were cited by 66 percent of the responding schools as the major reason for not accepting all qualified applicants [1].

According to a Special Survey on Vacant Faculty Positions released by AACN in September 2010, a total of 880 faculty vacancies were identified in a survey of 556 nursing schools with Baccalaureate and/or graduate programs across the country (70.3% response rate). Besides the vacancies, schools cited the need to create an additional 257 faculty positions to accommodate student demand. These data show a national nurse faculty vacancy rate of 6.9%. Most of the vacancies (92.6%) were faculty positions requiring or preferring a doctoral degree. The top reasons cited by schools having difficulty finding faculty were noncompetitive salaries compared to positions in the practice arena (30.2%) and a limited pool of doctorally-prepared faculty (30.4%) [2].

Worsening faculty shortages in academic health centers are threatening the nation’s health professions educational infrastructure, according to a report by the Association of Academic Health Centers released in July 2007. Survey data show that 94% of academic health center CEOs believe that faculty shortages are a problem in at least one health professions school, and 69% think that these shortages are a problem for the entire institution. The majority of CEOs identified the shortage of nurse faculty as the most severe followed by allied health, pharmacy and medicine [2].

At present, there are approximately 3500 nursing programs, in nearly 2500 schools of nursing. These schools enroll a total of approximately 300,000 students. With the projected “shortfall” of nurses to meet the health care needs of our increasingly diverse and aging population, schools may need to increase their enrollments by as much as one-third to “fill the gap,” bringing the ideal number of enrolled students close to 400,000. Using a ratio of 10:1 (students: faculty), the number of full-time faculty required to teach those 400,000 students enrolled in today’s 3500 programs may be as high as 40,000. Current data suggest we now have less than 50 percent of that number. This is particularly alarming in Alabama where a large number of qualified students are turned away because of nursing faculty shortages in a state with many health disparities. The supply of individuals available to meet this demand is shrinking rapidly as the result of three phenomena: the retirement of large numbers of faculty (many of whom were prepared as educators), the limited number of graduate programs that offer options to specialize in nursing education, and the declining enrollments in graduate programs that prepare nurse educators [3].

Most severely hit by nursing and nursing faculty shortages are underserved rural communities (US Department of Health and Human Services, Health resources and Service Administration, 2003). They are and will continue to experience shortages of nurses both at the basic and advanced levels of practice. The problem is multifaceted, partly because the health professions schools, community colleges and universities that serve as feeders to the rural areas are experiencing a decline in the number of qualified faculty and there are other positions for experienced nurses that pay more and include better working conditions. Potential faculty are choosing alternative careers and licensed nurses are gravitating toward more lucrative pay, better benefits, top notch equipment, and more enticing social aspects of metropolitan areas [4]. Even when applications to nursing programs increase, potential admissions are decreased because of faculty shortages Nursing schools in Alabama lack sufficient faculty to admit more students to nursing education programs. In 2006, there were a total of 24 nursing faculty vacancies in Alabama and at least 56 faculty who reportedly, may be retiring over the next five years [5]. Over 1325 students were turned away from nursing programs in Alabama in 2005-2006 because of the nursing faculty shortage. A 90 percent increase in the number of graduates is required to even begin alleviate the current shortage in the state [5]. If Alabama continues to have a decline in enrollment combined with the current and expected faculty shortages, the State of Alabama may be headed for a nursing care crisis of major proportions.

To ensure an adequate supply of competent nurse educators, the National League for Nursing [3] has urged the nursing education community to provide increased opportunities in graduate programs to prepare faculty and to support faculty development activities. The NLN also strongly advocates that careers in nursing education be promoted vigorously to talented neophytes and experienced nurses who have already demonstrated nurse educator skills and that funding to support the preparation of nurse educators and the development of the science of nursing education be increased significantly. In light of the looming crisis in the supply of faculty to teach in schools of nursing, the time has come for the nursing profession to outline a preferred future for the preparation of nurse educators. This crisis must be used as an opportunity to recruit qualified individuals to the educator role, to ensure that these individuals are appropriately prepared for the responsibilities they will assume as faculty and to implement strategies that will serve to retain a qualified nurse educator workforce. The NLN [3] asserts that the nurse educator role requires specialized preparation and every individual engaged in the academic enterprise must be prepared to implement that role successfully. In addition, each academic unit in nursing must have a cadre of experts in nursing education who provide the leadership needed to advance nursing education and conduct pedagogical research.

Most recently, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) Report [6] emphasized the need for nurses to achieve higher levels of education in order to provide the highest quality of patient care. It follows then that nurse educators must also achieve higher levels of education to insure that nursing education is on the cutting edge of practice and that students’ attainment of educational outcomes will promote quality patient care. Nurse educators must also be comfortable with the newest technologies and educational approaches to promote student learning.

Based on these identified nursing faculty needs and recommendations, the College of Nursing and the College of Education, Department of Instructional Technology, collaborated to provide a doctoral program to prepare nurse educators. Most nurses entering the program possess an MSN degree in a clinical area, and earn an EdD. for Nurse Educators degree. Nurses with BSN preparation are encouraged to complete the MSN and EdD through a dual degree option.

2. RATIONALE FOR AN EDD PROGRAM

The ultimate rationale for providing a nurse educator program is to create a pipeline for nursing faculty in Alabama. By increasing the number of faculty to teach in programs throughout the state, the number of potential nurses that can be admitted to nursing programs increases. As the number of nurses available to the population increases so does the rural population’s access to quality health care.

Another important rationale for providing the EdD. for Nurse Educators program is that faculty from both two and four year programs can obtain a doctorate thereby enhancing opportunities for doctoral level knowledge acquisition and progression in the faculty role. This program also facilitates promotion of MSN prepared faculty in academic settings. Colleges in the state will benefit from the program by retaining more qualified faculty and facilitating the recruitment of young faculty. The rationale for providing the EdD. rather than the Ph.D. degree is that the EdD. focuses on curriculum development and teaching practices that are most needed in traditional education settings. Graduates of the EdD. for Nurse Educators program also have a strong foundation in research both in coursework and in the development of and successfully defending a research based dissertation that will provide the foundation for continuing research in an academic setting.

3. ASSESSMENT OF NEED FOR THE PROGRAM

To determine the applicant pool in Alabama for a nurse educator program, five groups were surveyed that were potential pipelines for the program. The survey also assessed whether online, blended format or traditional class meetings on a weekend basis would be well received. The five groups surveyed included: 1) graduates of the college’s MSN program; 2) faculty from the Associate Degree nursing programs in the state; 3) current MSN students; 4) current RN/BSN students and, 5) senior baccalaureate nursing students. Interest in the program was greatest among alumnae and community college faculty. The interest among community college faculty was not surprising because the community college faculty and administrators at schools throughout the state had long encouraged the College of Nursing to provide nurse educator preparation at the graduate level. The survey also revealed that the majority of respondents believed that the combined online and blended course delivery formats were “just right” for such a program.

4. PROGRAM DEVELOPMENT

On the basis of the survey described above, a proposal was submitted to the Dean of the College of Nursing outlining the proposed refinement of the existing EdD. program in the College of Education to focus on preparation of practicing nurses for the nurse educator role. The Dean of Nursing was enthusiastic about the proposed EdD. option for nurse educator preparation and she contacted the Dean of the College of Education to discuss the proposal. The Dean of the College of Education was also delighted that an interdisciplinary option for nurse educators was being considered between the two colleges. The two Deans then met with the Provost of the University to determine if the plans for the program were viable. The Provost gave strong support to the proposed program for nurse educators. A planning group was selected by both Deans to further explore refinement of the existing EdD. program for nurse educators as an interdisciplinary option between the two colleges. It was decided that the Instructional Leadership department in the College of Education would best match the needs and competencies of nurse educators and would serve as the foundation for the program.

The interdisciplinary planning group included selected faculty from the Colleges of Nursing and Education. A liaison from the Instructional Leadership program and a faculty member, who taught instructional technology in Instructional Leadership, were included in the planning group. The interdisciplinary planning group met frequently over several months to discuss topics such as, the existing EdD. program, educational needs of nurses at the doctoral level, collaboration between the two faculty groups for advisement of students, application of existing graduate school policies, and recruitment and admission of nurses to the program. A major focus of the groups’ efforts was focused on planning the curriculum for coursework in the program. Competencies developed by NLN [7] and the Council on Collegiate Education for Nursing [8] were used to guide curriculum development and planning of didactic assignments, and were used extensively to plan learning activities for the nurse educator practicum course. These competencies were also used as a content guide to develop and/or modify the content and coursework for existing EdD. courses that were refined for the nurse educator students. Program outcomes, competencies and a program of study were outlined and approved by the faculty of both colleges.

To determine the types of information that should be included in the nurse educator program, a survey was distributed to faculty members with MSN level preparation who had limited teaching experience. The faculties were asked to identify content areas they believed would have been helpful to them when they first began their faculty role. These topics were then discussed in a focus group format. Based on this input, a review of course content in the EdD. program, a review of literature regarding nursing education curricula, and the knowledge and expertise of senior faculty, several nursing courses were developed to supplement the existing EdD. coursework. Among the courses developed were: 1) faculty roles and responsibilities, 2) instructional media in nursing education, 3) a research course in the final semester of coursework, and 4) a capstone teaching experience near the end of the program.

The faculty roles and responsibilities course provides the student with an overview of the faculty role and how the faculty member serves as an advisor, teacher, clinical instructor, mentor and evaluator. Course content also includes those tools and processes that assist faculty in organizing and planning instruction using a variety of formats, structures and strategies. It emphasizes the curriculum development that is required in nursing education. Although the College of Education had courses that focused on teaching roles, those courses lacked the emphasis on a nursing faculty role and those responsibilities that are quite different from other disciplines, such as teaching nursing skills.

A course in instructional media for nurses was also developed. It is clear that there are a number of courses in the traditional EdD. program that prepare instructors to develop online coursework as well as use a variety of software, models and other instructional devices. However, nursing education uses a variety of approaches and learning situations that are different from other disciplines, such as simulation of clinical scenarios. Nurse educators also may supervise the use of personal digital assistant (PDA) devices and computers in the clinical area, and patient simulators may be integrated into instruction but must make sense given the skills and content being presented. Therefore, this course that includes media specific to nursing and its use in both didactic and clinical instruction was included.

The research course, located in the final semester of the program of study, promotes student’s completion of the first draft of the essential components of the dissertation. The course is taught by nursing faculty who guide students through the process of elucidating a reasonable research topic and approach for the research.

Also, important was the inclusion of a capstone experience in which students work under the direction of a doctorally prepared nursing faculty member to provide opportunities for gaining experience and faculty role modeling within a school or college of nursing. The students also need opportunities to practice clinical and didactic instruction within the nursing education setting. This course promotes students’ awareness of the specific standards, regulatory bodies and accreditation criteria used in nursing education. Students will also use a checklist in the capstone experience that is a synthesis of the competencies delineated by NLN [7] and SCCEN [8]. These competencies guide and tailor the experience to the student’s individual learning needs. The checklist also provides preceptors with guidelines for supervising students within their classroom and clinical instruction experiences during the practicum in the capstone course. Some components of the capstone experience may also take place in the simulation center in the College of Nursing.

Based on the preliminary survey data, the advisory team developed the curriculum delivery modalities to include several formats, all of which are designed to be accessible to nurses who are employed full-time. For example, some courses are offered in a traditional classroom format with class meetings on four Fridays and Saturdays during the semester. Some courses also integrate student and faculty interaction via web-supported course instruction modalities. Other courses provide instruction using a totally online format. These alternative course delivery modalities are designed to satisfy the personal and professional needs of students while ensuring that the program meets the expectations of the fully rigorous doctoral program in instructional leadership for nurse educators.

Students also complete a comprehensive examination to determine competence in the student’s broad area of knowledge as reflected in the coursework taken during the doctoral program. This comprehensive exam uses a case study format with questions developed by faculty from the colleges of nursing and education. The program faculty (both nursing and education) have the responsibility for constructing an examination that reflects the body of knowledge in the program.

Students must also complete a research-based doctoral dissertation. Students select a committee of faculty from both the Colleges of Nursing and Education, Instructional Leadership program to guide their dissertation research. The dissertation committee assists the doctoral student in developing and conducting the dissertation, starting with the work completed in the nursing research course previously described.

Based on the curriculum that was developed, and on the existing faculty and other resources in both colleges, a cohort model was chosen for implementation of the program. The planning group agreed that approximately 20 students admitted every two years would be a workable size group to start the program. An advantage of the cohort model and the delivery modalities previously discussed was that courses can be scheduled exclusively for these students so they have the nurse educator focus throughout the program.

Programs of study were also developed for the MSN/ EdD. and EdD. for Nurse Educators programs to assure that courses are offered in both colleges in the sequence needed for timely completion of coursework. Also considered in preparation of the programs of study was the need for community college faculty to complete blocks of coursework in specified time frames to be eligible for promotions during doctoral study. Including this consideration in developing the program of study was crucial to receiving the support of the statewide community college governing body for the degree to be recognized as acceptable for promotion within the community college system.

5. STUDENT RECRUITMENT

The advisory committee shared information about the program with the Office of Post Secondary Education that oversees nursing education in community colleges in the state, to gain their support. The Deans and Directors of university, private and community college nursing programs were also informed about the program. Brochures about the program were developed and distributed widely within the nursing community. The response to the initial program information was gratifying. With limited publicity, more than one hundred inquiries were received about the program. A website was also developed to provide program information to prospective students. The website includes the program of study, admission criteria, and other useful program information as well as links to the Instructional Leadership and College of Nursing faculty, and to the Graduate School. Access to an application form is also linked on the website.

6. FACULTY DEVELOPMENT

To facilitate a culture of interdisciplinary collaboration and scholarship, the faculties from both colleges have conducted day long retreats. The first retreat focused on the ways the faculty in instructional leadership could refine existing courses to meet the educational needs of doctoral nursing students and to provide opportunities for nursing faculty to become conversant with course content and outcomes in instructional leadership. Subsequent retreats have focused on continuing collaboration among the faculties with discussion about emerging issues, and promotion of student success in the developing program. The retreats have provided a relaxed atmosphere to promote interaction and socialization among the faculty groups.

7. ADMISSION OF FIRST COHORT

The admissions committee was composed of faculty from both colleges. It was interesting to note that there was consensus about the quality of applicants among faculty from both colleges when reviewing application materials and writing samples. Twenty-nine nurses completed the application process. An interdisciplinary group of faculty from both colleges reviewed applications and selected the most qualified applicants for admission. Twenty three applicants were selected for admission and twenty two enrolled. Of that number, all but two were working as a faculty member. However, those two were interested in pursuing a faculty position during or after completion of the program. Seven of the 22 students (32%) were ethnic or racial minorities, two (9%) were males and the remainder were Caucasian. It is obvious that one of the most effective program marketing strategies was disseminating program information to colleges and universities in the state and in nearby states by enlisting the assistance of existing College of Nursing partnerships with community colleges in the state.

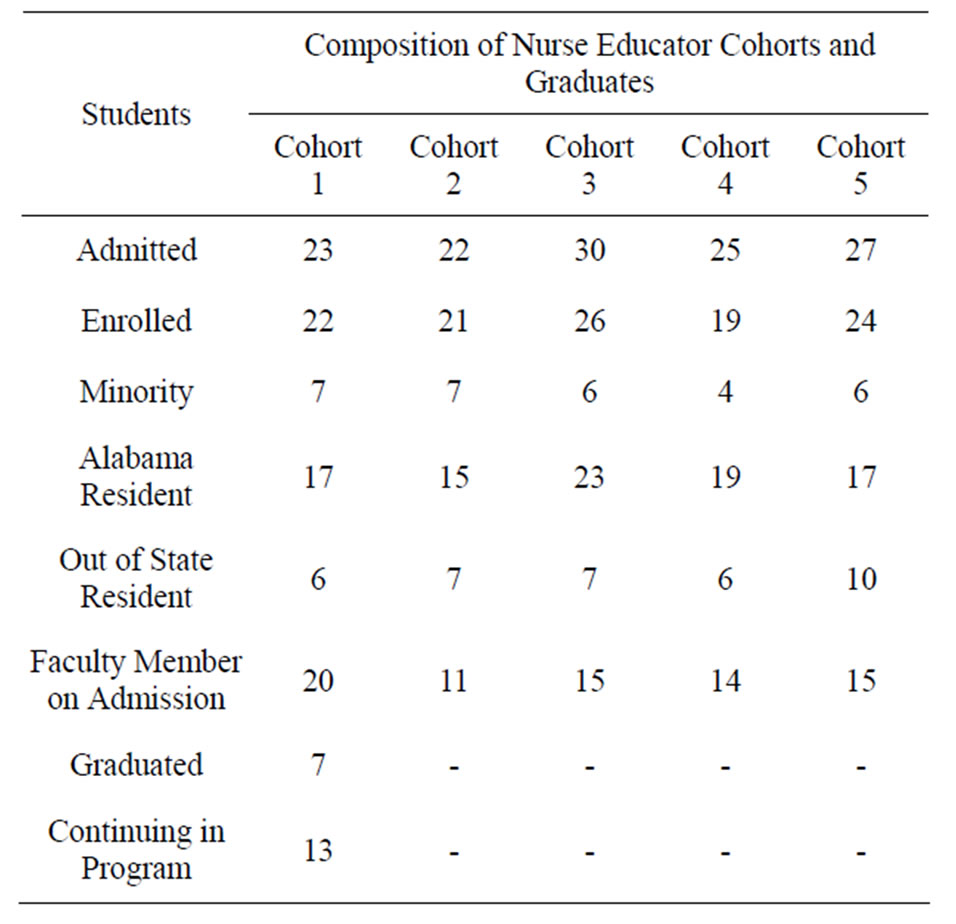

Four additional cohorts of 25 or more students have been admitted each year since the initial cohort was admitted in the fall of 2007 (Table 1). Interest in the program has grown dramatically with inquiries and enrollment of students extending well beyond the southeastern states as noted in Table 1.

Because this program is a new endeavor on our campus, major efforts were undertaken to assure that coordination of the program was seamless in meeting the new students’ entry needs. For example, a faculty person from the College of Nursing assisted students with obtaining books, following administrative paperwork, obtaining email accounts, hotel reservations, parking permits and campus tours. Dedicating a faculty member initially to respond to student issues and address their ongoing needs between admission and program implementation was very effective. A staff member also was hired to focus on student recruitment, and mentoring throughout the program to promote retention and graduation. Initially the staff position was funded by the two colleges but once the program enrollment produced sufficient funds, the position has been funded by the program rather than the colleges. The website previously described was also further refined to include information relevant for current students. The website is updated frequently to provide information needed by students.

Another strategy used to assure that the needs of the new students in this program were met was to hold an orientation to the program on the first day of program classes with welcomes by the Provost, both Deans, and the interdisciplinary advisory group members. All College of Nursing graduate faculty and College of Education Instructional Leadership faculty were invited to the

Table 1. Composition of nurse educator cohorts and graduates.

orientation to meet the students and converse with them. Students also heard presentations about the nurse educator program from faculty, and there was a question and answer period. It was an exciting day for faculty and students to meet and learn more about each other as well as about the program. This orientation to the program has become an annual event with opportunities provided for new students to talk with students further along in the program who share sage advice about strategies for success in the program. Opportunities are also provided for continuing students to share issues or requests for change. For example, a recent group noted the difficulties they were having with parking which was resolved by administration.

The culture of the interdisciplinary faculty group is also very positive and supportive. Many issues have arisen as program refinement and implementation have progressed; however, problems are quickly referred to faculty for input and problem solving. Because solutions are not stove piped but collaboratively engineered, there is a high degree of faculty satisfaction and motivation.

8. SUMMARY

In summary, the nurse educator program provides an excellent mechanism for preparing nursing faculty. As a result of the program refinement process described here, there are several recommendations for those colleges that anticipate developing an interdisciplinary degree for nurse educators. Based on the experience at this academic institution, the following recommendations are delineated.

1) Begin the process of collaboration about an interdisciplinary graduate program at least two years prior to implementation. It takes time for administration as well as faculty to fully support the idea. Time is needed to move the plan through the curriculum committees of both schools as well as any graduate or other internal review groups. More time will be required if external approvals are needed.

2) Use an interdisciplinary group as an advisory and steering group. Membership needs to include chairs and faculty from both disciplines.

3) Assure that administration in both colleges as well as the University is committed to the program. Provide multiple opportunities for dialog among faculty from both colleges, such as retreats and meetings. Provide a list of research interests and potential teaching responsebilities facilitates dialog.

4) Resolve administrative, support and logistical matters through mediation by the interdisciplinary advisory group.

5) Resolve curricular issues through communication between faculty in both colleges.

6) Establish a culture that is supportive of and fosters interdisciplinary scholarly activity.

7) Use academic partnerships and alumnae to promote the program.

8) Assess the educational needs of potential applicants e.g., flexibility in course offerings such as blended or online courses offer.

9) Provide follow up and support for applicants during the application process.

10) Maximize access to the program. Applicant pools can be surveyed to determine preferences about access and timing.

11) Appoint one staff or a faculty member to mentor students from the time of admission until courses begin to facilitate meeting adult learners’ entry needs. A single person makes this process less difficult for new students to navigate.

12) Provide program specific information on a new or existing website for the program. Update it frequently to provide necessary information to prospective and current students.

13) Promote collaboration among faculty from both colleges for student advisement, progression and completion of dissertations.

14) Provide students with an orientation early in the program that includes advisors and other faculty. This is especially important if the program is online or includes a significant portion that is web-based.

This list is probably not exhaustive, but we believe it is important to share successes. The shortage of nurses and nursing faculty requires that we develop solutions and this report is one that may work for other colleges as well. Sharing best practices or lessons learned may assist other institutions to consider an interdisciplinary degree as a strategy to increase the number of nurse faculty.

9. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Dr. Natalie Adams, Dr. Vivian Wright, Dr. John Petrovik and Dr. Stephen Tomlinson to the program.

REFERENCES

- Health Resources and Services Administration (2003) Changing demographics: Implications for physicians, nurses and other health workers. Hhttp://bhpr.hrsa.gov/healthworkforce/reports/changedemo/default.htmH.

- AACN Task Force on the Faculty Shortage (2011) Faculty shortage in baccalaureate and graduate nursing programs: Scope of the problem and strategies for expanding the supply. American Association of Colleges of Nursing, Washington DC.

- National League for Nursing (2006) Core competencies for nurse educators. Hhttp://www.nln.org/profdev/corecompetencies

- Satcher, D. and Pamies, R.J. (2006) Multicultural medicine and health disparities. McGraw Hill, New York.

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing (2006) Survey of twoand four-year colleges of nursing with the State of Alabama.

- Institute of Medicine (2010) The future of nursing, leading change, advancing health. National Academies Press, Washington DC.

- National League for Nursing (2006) Nurse faculty supply continues to fall short. Hhttp://www.nln.org/newsreleases/nurseeducators2006.htm

- Council on Collegiate Education for Nursing (2002) Southern Region Education Board (SREB) study indicates serious shortage of nursing faculty. Hhttp://www.sreb.org/programs/nursing/publications/pubindex.asp