Open Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology

Vol.3 No.1A(2013), Article ID:27777,5 pages DOI:10.4236/ojog.2013.31A039

Double balloon device compared to oxytocin for induction of labour after previous caesarean section

![]()

1Departament of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Donostia Hospital, San Sebastián, Spain

2Departament of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Asturias Central Hospital, Oviedo, Spain

Email: fefirodriguez@gmail.com

Received 6 December 2012; revised 8 January 2013; accepted 17 January 2013

Keywords: Double Balloon Device; Induction; Labor; Vaginal Birth after Caesarean; Cervical Ripening

ABSTRACT

Objective: To assess cervical changes, duration of oxytocin infusion, mode of delivery and complications after cervical ripening using a double balloon device in women with a previous caesarean section. Methods: Longitudinal study including 80 women with a previous caesarean section, no previous vaginal delivery and an unfavourable cervix (Bishop score < 4). Two groups were established: a double balloon device was used with 32 women (exposed) and not with the others (non-exposed) (48). Statistical analysis was performed by comparing means (Student’s t-test and Welch’s test or paired Student’s t-tests), or by comparing proportions (Chi square or Fisher’s tests). Results: The mean number of hours of oxytocin infusion was statistically significantly higher in the nonexposed group (14.09 ± 6.05 vs 9.78 ± 3.95; p < 0.001), and in the exposed group the Bishop score increased after removing the double balloon device (3.22 ± 2.03 vs 1.16 ± 1.30; p < 0.01). There were no significant differences in the mode of delivery, rates of intrapartum fever or chorioamnionitis. Conclusion: The double balloon device for cervical ripening prior to induction with oxytocin in women with a previous caesarean section improves Bishop scores without increasing the rates of complications and decreasing the time for which oxytocin is required.

1. INTRODUCTION

In recent years, there have been upward trends in the rates of labour induction and percentages of caesarean sections [1]. Accordingly, now and in the future, we are likely to more and more often face the need to induce labour in women with previous caesarean sections. The main problem in such cases is the presence of uterine scars, which increase the risk of uterine rupture and, as a consequence, an increase in maternal and foetal morbidity and mortality.

One of the most important predictive variables for assessing the likelihood of having a vaginal delivery is the Bishop score [2] which evaluates the state of the cervix. Unfortunately, some women in whom induction is indicated have an unfavourable cervix, and in these cases pharmacological and mechanical methods are used to achieve cervical ripening. It has been shown that the use of pharmacological methods (E2 prostanglandin and misoprostol) in a group of patients with previous caesarean section increased the risk of uterine rupture (2.4%), compared to spontaneous onset of labour (1%), so such methods are not recommended in these women [3].

Mechanical methods include the use of transcervical balloon devices described for the first time in 1967 [4], which work directly by applying pressure and stretching the lower uterine segment and cervix, as well as by favouring the release of natural prostaglandins. To date there are insufficient data to evaluate such mechanical methods compared to placebo or prostaglandins. It does seem to be clear, however, that the risk of uterine hyperstimulation is lower than with prostaglandins and that their use is not associated with a significant increase in the risk of uterine rupture compared to spontaneous delivery [5]. Further, cervical stimulation with a mechanical device seems to be more effective than labour induction with oxytocin [6].

The objective of this study was to assess the effectiveness and safety of double balloon device for cervical ripening in women with a previous caesarean section and no previous vaginal deliveries.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

This is a longitudinal cohort study that included women with a history of caesarean section and an unfavourable cervix (Bishop score < 4 and cervical dilation < 2 cm) who were admitted to Donostia Hospital for the induction of labour between January 2005 and June 2011. The exclusion criteria were: non-cephalic presentation, premature rupture of membranes, metrorrhagia in the third trimester of pregnancy and a history of vaginal delivery.

Two groups were established: women in whom a double balloon device was used (exposed) and the others (non-exposed). The non-exposed group consisted of women who were induced with oxytocin, without use of a balloon device, as they were admitted to hospital for labour induction between January 2005 and December 2008, that is, before a protocol indicating use of balloon catheters was introduced. For the exposed group we recruited all women attending the hospital for induction of labour from January 2009, when the policy changed, until June 2011.

The following variables were collected from all the women included in the study: their age, date of delivery, gestational age, cause of previous caesarean section, reason for induction, Bishop score prior to induction, duration of oxytocin infusion, mode of delivery and reason in event that caesarean section is required, as well as indicators of complications such as uterine rupture, intrapartum fever and chorioamnionitis. Uterine rupture was diagnosed when it was symptomatic and/or required surgical intervention. Cases of asymptomatic scar dehiscence were not included, as they do not have clinical repercussions and, in addition, in our hospital there is no systematic protocol for reviewing previous caesarean section scars and recording any changes. Intrapartum fever was defined as a body temperature ≥ 37.8˚C during labour, and chorioamnionitis was diagnosed as indications of infection on histological analysis of the placenta.

The following additional variables were recorded for those in whom double balloon devices were used to achieve cervical ripening: Bishop score after removal of the double balloon device, duration of catheter placement, and inflation volume of the intraand extrauterine balloons.

Before the change in policy (introducing balloon catheters), the protocol for labour induction was artificial rupture of membranes, when possible, followed by oxytocin infusion. In the cases in which artificial rupture of membranes was not possible, oxytocin infusion was initiated until it became possible. Oxytocin infusion was initiated at 2 mU/ml, doubling the dose every 20 min until 210 Montevideo units of uterine activity or 16 mU/ min. If this dose was reached and there was insufficient uterine activity, we increased the dose by a further 4 mU/ min, the maximum being 20 mU/min.

If after 12 h labour had not progressed to the active phase, defined as the cervix being at least 3 cm dilated and fully effaced, induction was considered to have failed, and caesarean section was indicated.

Cesarean section was also indicated for first and second stage of labor arrest after four hours with a sustained uterine contractil pattern [7] and non reassuring foetal status. This indication required a scalp pH value of < 7.20 as a critical value or a fetal heart rate monitoring classified in the third category of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development [8].

In the process of inducing labour involving balloon devices, the first step was to explain the protocol to the patient. A double balloon device (Cook® cervical ripening balloon) (Cook Medical Inc., Bloomington, Indiana) was then placed using a speculum. The device was introduced through the external orifice of the uterus, and the intrauterine balloon was then filled with 20 ml of saline. After checking that it was correctly placed, the extrauterine balloon was filled with the same volume (20 ml) of saline. Subsequently, more saline was pumped into the intrauterine balloon until the patient reported pain, in which case the volume was reduced slightly until the pain eased, or until a maximum volume of 80 ml.

During the time that the patient had the catheter in place, foetal well-being was continuously monitored, and after its removal the Bishop score was assessed. Oxytocin induction of labor was carried out within 8 hours from balloon removing, following the same protocol as for the induction without the use of this mechanical method (described above).

Statistical analysis was carried out using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) (version 15.0 for Windows). Continuous variables were described by means and standard deviation (SD), while proportions were calculated for categorical variables. The association between the variables was assessed by comparing the means using the Student’s t-test and Welch’s test or the paired Student’s t-test, and comparing proportions using the Chi square or Fisher’s tests. Statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.05.

3. RESULTS

A total of 75 women with previous caesarean section who were admitted to Donostia Hospital for induction between January 2005 and December 2008 were identified and their medical records reviewed: 27 women were excluded from the study, 16 because of premature rupture of membranes and 11 because they had a Bishop score ≥ 4 and/or a cervical dilation ≥ 2 cm, and 48 women were included in this group. Between January 2009 and June 2011, 36 women with a history of caesarean section were induced under the new protocol, involving the placement of a double balloon device for cervical ripening prior to the administration of oxytocin: 4 women were excluded, 2 because of premature rupture of membranes and 2 because they had had previous vaginal deliveries, and 32 women were included in this group.

Spontaneous expulsion of the balloon was not observed in any of the participants. Catheters were in place for a mean of 11.19 hours, ranging from 5 to 14 hours. The mean volume of saline pumped into the intrauterine balloon was 55 mL, ranging from 30 mL to 80 mL, while the mean volume used for the extrauterine balloon was 29.7 mL, ranging from 20 mL to 80 mL.

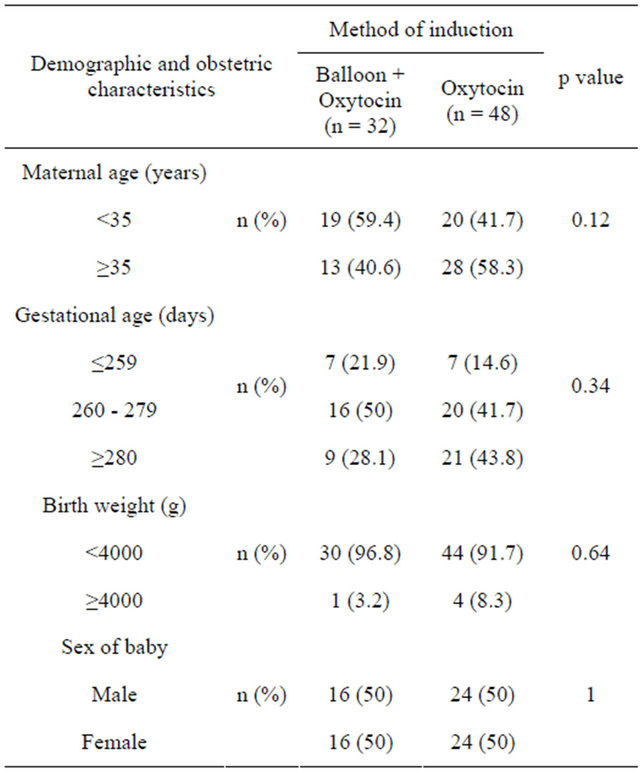

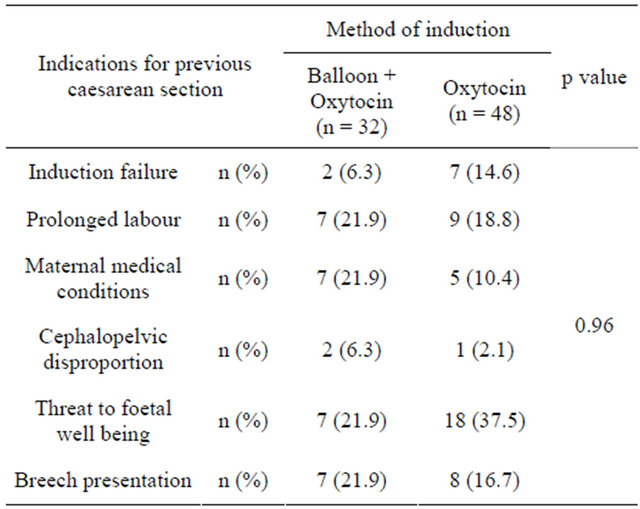

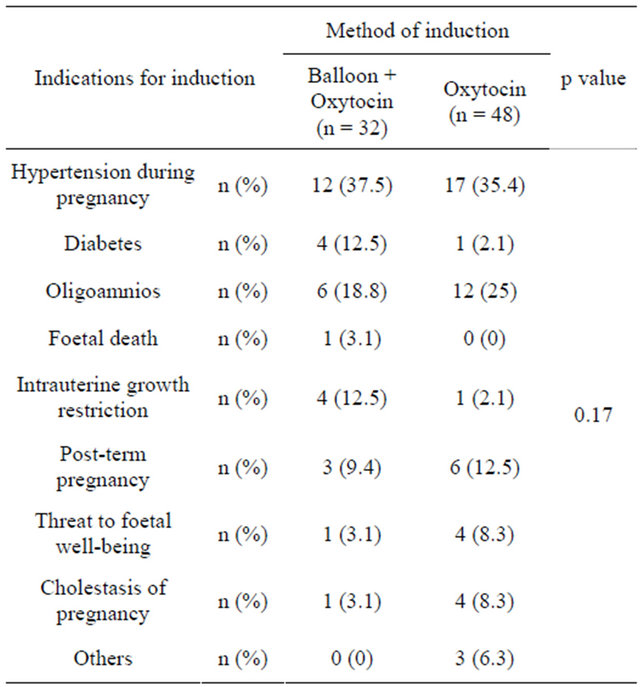

Demographic and obstetric data of the groups and their comparison are detailed in Table 1. We did not find any statistically significant difference in any of the variables analysed. Further, we found no statistically significant differences as a function of the reason for previous caesarean section (Table 2), the indication for induction (Table 3), or the Bishop score prior to starting the induction protocol between the groups of women who subsequently did and did not have double balloon device placed (1.16 ± 1.30 vs 1.06 ± 1.26; p = 0.75).

The outcomes of the two induction methods are shown in Table 4. There was a statistically significant difference in the duration of oxytocin infusion used for induction between the groups, namely less oxytocin was required after use of the balloon device. There was one case of symptomatic uterine scar dehiscence time after removing the double balloon device; this had an effect on the foetal heart rate and, accordingly, the baby was delivered by caesarean section. No significant effect on the condition of mother and foetus was detected in any other cases.

Table 1. Demographic and obstetric characteristics of the two groups of women.

Table 2. Reasons for previous caesarean section in the two groups of women.

Table 3. Indication for labour induction in the two groups of women.

In the group of women in whom a double balloon device was placed, the mean Bishop score after its removal was 3.22 ± 2.03. This was found to be significantly different with respect to the Bishop score prior to catheter placement (p < 0.001), indicating that the placement of a double balloon device increased the Bishop score and hence improved the situation prior to induction with oxytocin.

4. DISCUSSION

This study shows that the use of a double balloon device for cervical ripening in women with previous caesarean

Table 4. Comparison of obstetric variables in the two methods of induction.

aIn the data for the duration of oxytocin infusion, 6 and 2 women were excluded from the groups in which the balloon device was and was not used respectively as delivered by caesarean section due to threats to foetal wellbeing.

section increases the Bishop score prior to induction with oxytocin, leading in turn to a decrease in the duration of administration of the drug, without increasing the rate of complications.

Changes in the Bishop score after the use of simple balloon devices have been investigated previously. In 1996 Sherman et al. [9] assessed its use in a series of 190 primiparous and multiparous women (41%), excluding women with previous caesarean section. The Bishop score was initially 1.5 ± 0.1, that is, before the introduction of a simple balloon catheter (Foley® catheter) (CR Bard, New Jersey) and after its removal had risen to 5.5 ± 0.1.

There have, however, been few studies investigating cervical ripening with a balloon device in women with a previous caesarean section. In 1997, Atad et al. [10] published their results using a double balloon device without excluding women with previous caesarean section, but did not report the results in this subgroup and the sample included primiparous and women with previous vaginal deliveries. Consistent with our results, the authors reported an increase in the Bishop score after removal of the balloon of on average 4.6 points (p < 0.05). In 2001, Khotaba et al. [11] published a study of 37 pregnant women with a previous caesarean section who were induced using a double balloon device. Among the 24 women who completed a vaginal delivery, the difference in the Bishop score before and after placing the balloon was significant (p < 0.01), while it was not significant with group of 10 women who finally underwent Caesarean section. On the other hand, this study did not exclude women with previous vaginal deliveries, the average number of deliveries being 2.7 ± 0.9.

Uterine rupture is one of the most serious complications in women with previous caesarean section. Given this, many studies have retrospectively compared results using various methods of cervical ripening and labour induction, including the use of simple balloon devices. The results published to date, however, are not consistent.

We highlight the study by Bujold et al. [12] who assessed the rate of uterine rupture in women with a history of previous caesarean section with spontaneous onset of labour, oxytocin induction or ripening with a simple balloon device. No statistically significant differences were found in the rate of uterine rupture when comparing the use of a simple balloon device and spontaneous onset of labour (OR 0.47; CI 95% 0.06 - 3.59). These results are in agreement with those published by Ravasia et al. [13] who did not find significant differences in the rate of uterine rupture between women with spontaneous onset of labour and those in whom a simple balloon device was used (p = 0.47). In this retrospective study, the effect of PGE2 gel was also assessed and results indicated a higher rate of uterine rupture among women who underwent cervical ripening with PGE2 gel compared to those with a spontaneous onset of labour (p = 0.004).

On the other hand, some authors have indicated a higher rate of uterine rupture after using simple balloon devices for cervical ripening. Hoffman et al. [14] observed an increase in the rate of uterine rupture in the groups in which simple balloon devices were used (OR 3.67; CI 95% 1.40 - 9.23) and misoprostol (OR 17.56; CI 95% 3.15 - 97.9), compared to that with spontaneous onset of labour.

Our study has some limitations that should be considered in interpreting the results. The inflation volume varied between the women. This variability was due to the fact that the inflation was stopped in cases when women reported pain. We adopted this policy when inflating the balloons, as pain during mechanical ripening may be counterproductive to the process. In addition, it has been noted that an increase in volume from 30 to 60 mL only represents an increase in diameter of 1 cm (from 3.9 to 4.9 cm), the balloons being spherical. Moreover, it seems that an excess of liquid in the balloon makes them become cylindrical, decreasing their effectiveness [9]. Another limitation of our study was in relation to the assessment of the mode of delivery. The number of women included in each group will have tended to reduce the statistical power of the analysis. Other authors [15] have been able to demonstrate a higher rate of vaginal deliveries in women in whom a double balloon device was used. These authors, however, excluded from their study women with a previous caesarean section.

Despite the aforementioned limitations, we have demonstrated the usefulness double balloon device for the induction of labour in women with a previous caesarean section and an unfavourable cervix. We have observed not only an increase in the Bishop score after using the balloon, but also a decrease in the duration of oxytocin infusion, compared with when induction was performed using this drug without prior use of a balloon catheter. In contrast to other studies published [11,16], we have obtained these results excluding women with previous vaginal deliveries. In this way, we avoid the potential bias that their inclusion may cause, since, as is well known, previous vaginal deliveries favour cervical ripening. Further, we have demonstrated that the use of double balloon devices in women with a previous caesarean section does not increase the rates of complications compared to induction with oxytocin straight away.

Our results are undoubtedly preliminary, but do indicate a new avenue to explore in the search for the ideal method for labour induction in women with a previous caesarean section and an unfavourable cervix. This group of women is not only exposed to a higher rate of mortality and morbidity secondary to the presence of a uterine scar, but also have a higher risk of labour induction failure due to an unfavourable cervix. Clearly, more randomised clinical trials are required to confirm these results.

REFERENCES

- Martin, J.A., Hamilton, B.E., Sutton, P.D., et al. (2009) Births: Final data for 2006. National Vital Statistics Reports, 57.

- Bishop, E.H. (1964) Pelvic scoring for elective induction. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 24, 266-268.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologist (2006) ACOG Committee opinion No. 342: Induction of labor for vaginal birth after caesarean delivery. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 108, 465-467. doi:10.1097/00006250-200608000-00045

- Embry, M.O. and Mollison, B.G. (1967) The unfavourable cervix and induction of labour using a cervical balloon. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology of the British Commonwealth, 74, 44-48. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.1967.tb03931.x

- SOGC (2005) SOGC clinical practice guidelines. Guidelines for vaginal birth after previous caesarean birth. Number 155. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 89, 319-331.

- Boulvain, M., Kelly, A., Lohse, C., Stan, C. and Irion, O. (2001) Mechanical methods for induction of labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 4.

- Garcia-Adanez, J., Navarro, M., Larraza, M.J., Ibañez, L. and Goiri-Little, C. (2010) “Four hour rule” increases vaginal birth after cesarean delivery. Advances in Perinatal Medicine, Monduzzi Editore.

- Macones, G.A., Hankins, G.D.V., Spong, C.Y., Aut, J. and Moore, T. (2008) The 2008 National Institute of Child Health and Human Development workshop report on electronic fetal monitoring: Update on definitions, interpretation, and research guidelines. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 112, 661-666. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181841395

- Sherman, D., Frenkel, E., Tovbin, J., Arieli, S., Caspi, E. and Bukovsky, I. (1996) Ripening of the unfavorable cervix with extraamniotic catheter balloon: Clinical experience and review. Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey, 51, 621-627. doi:10.1097/00006254-199610000-00022

- Atad, J., Hallak, M., Ben-David, Y., Auslender, R. and Abramovici, H. (1997) Ripening and dilation of the unfavourable cervix for induction of labor by a double balloon device: Experience with 250 cases. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 104, 29-32. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.1997.tb10644.x

- Khotaba, S., Volfson, M., Tarazova, L., Odeh, M., Barenboym, R., Fait, V., et al. (2001) Induction of labor in women with previous cesarean section using the double balloon device. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 80, 1041-1042. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0412.2001.801114.x

- Bujold, E., Blackwell, S.C. and Gauthieter, R.J. (2004) Cervical ripening with transcervical Foley catheter and the risk of uterine rupture. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 103, 18-23. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000109148.23082.C1

- Ravasia, D.J., Wood, S.I. and Pollard, J.K. (2000) Uterine rupture during induced trial of labor among women with previous cesarean delivery. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 183, 1176-1179. doi:10.1067/mob.2000.109037

- Hoffman, M.K., Sciscione, A., Srinivasana, M., Shackerlford, P. and Ekbladh, L. (2004) Uterine rupture in patients with prior caesarean delivery: The impact of cervical ripening. American Journal of Perinatology, 21, 217- 222. doi:10.1055/s-2004-828608

- Atad, J., Hallak, M., Auslender, R., Porat-Packer, T., Zarfati, D. and Abramovici, H. (1996) A randomized comparison of prostaglandin E2, oxytocin, and the doubleballoon device in inducing labor. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 87, 223-227. doi:10.1016/0029-7844(95)00389-4

- Miller, T.D. and Davis, G. (2005) Use of the Atad catheter for the induction of labour in women who have had a previous Caesarean section—A case series. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 45, 325-327. doi:10.1111/j.1479-828X.2005.00421.x.