Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

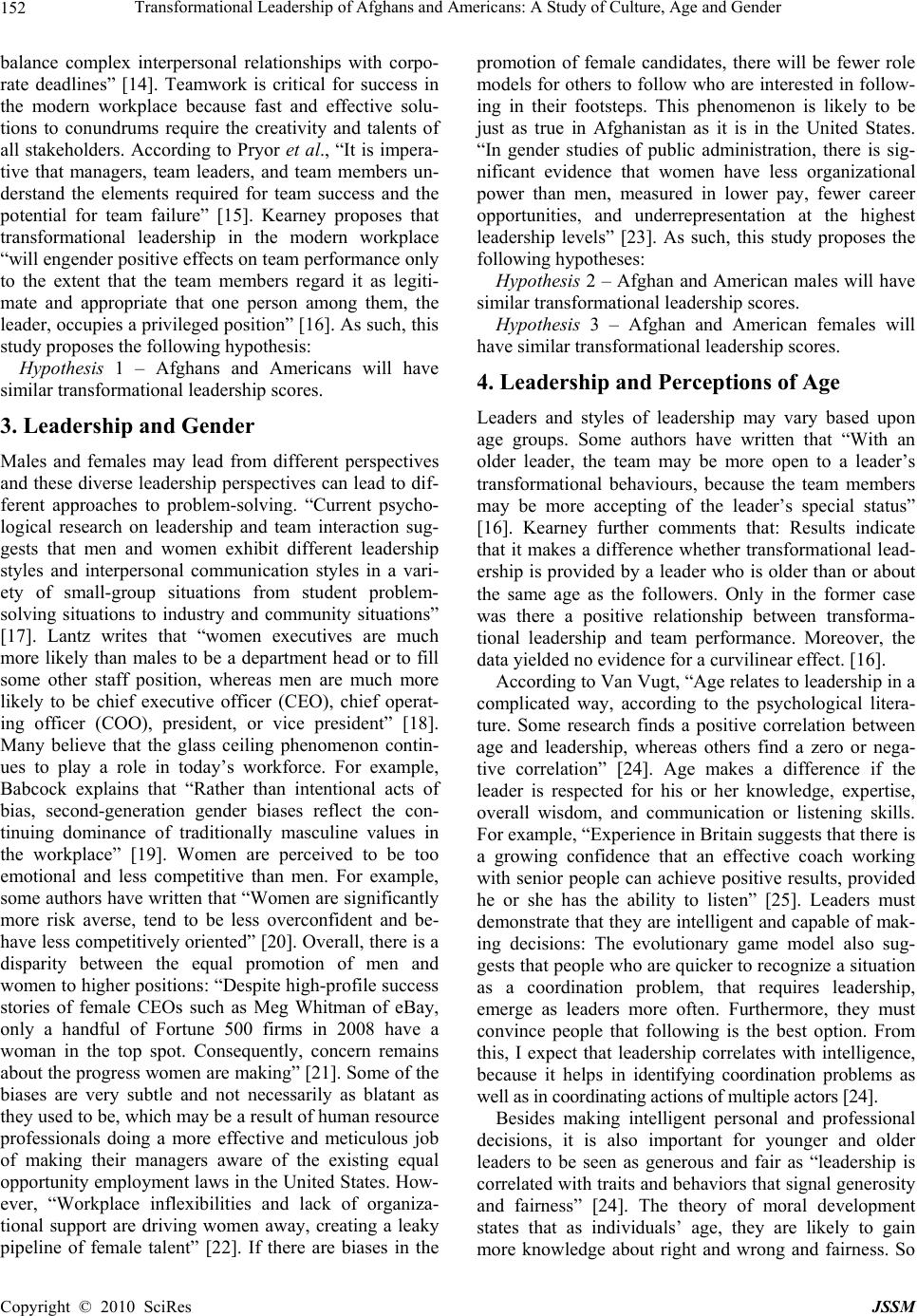

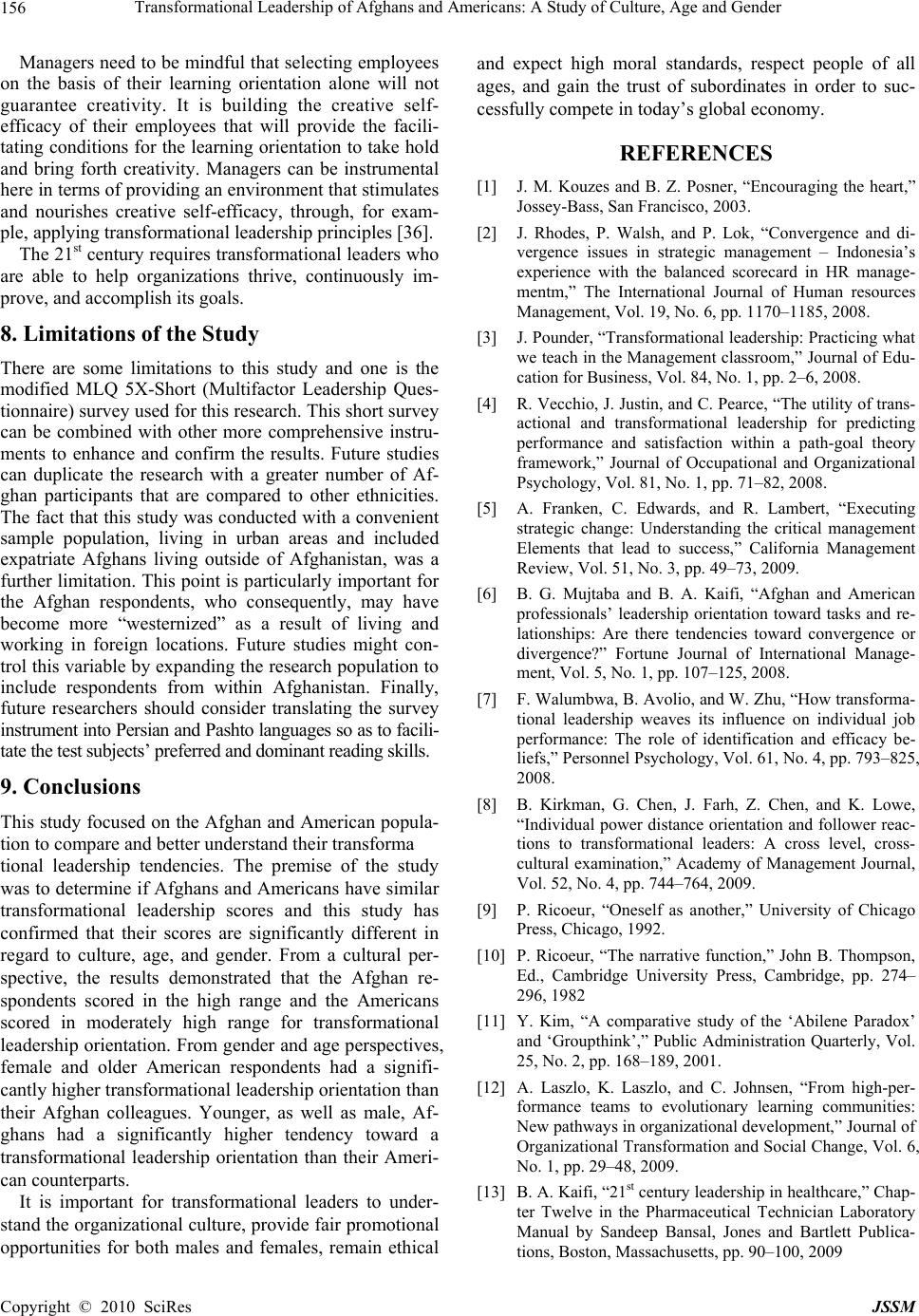

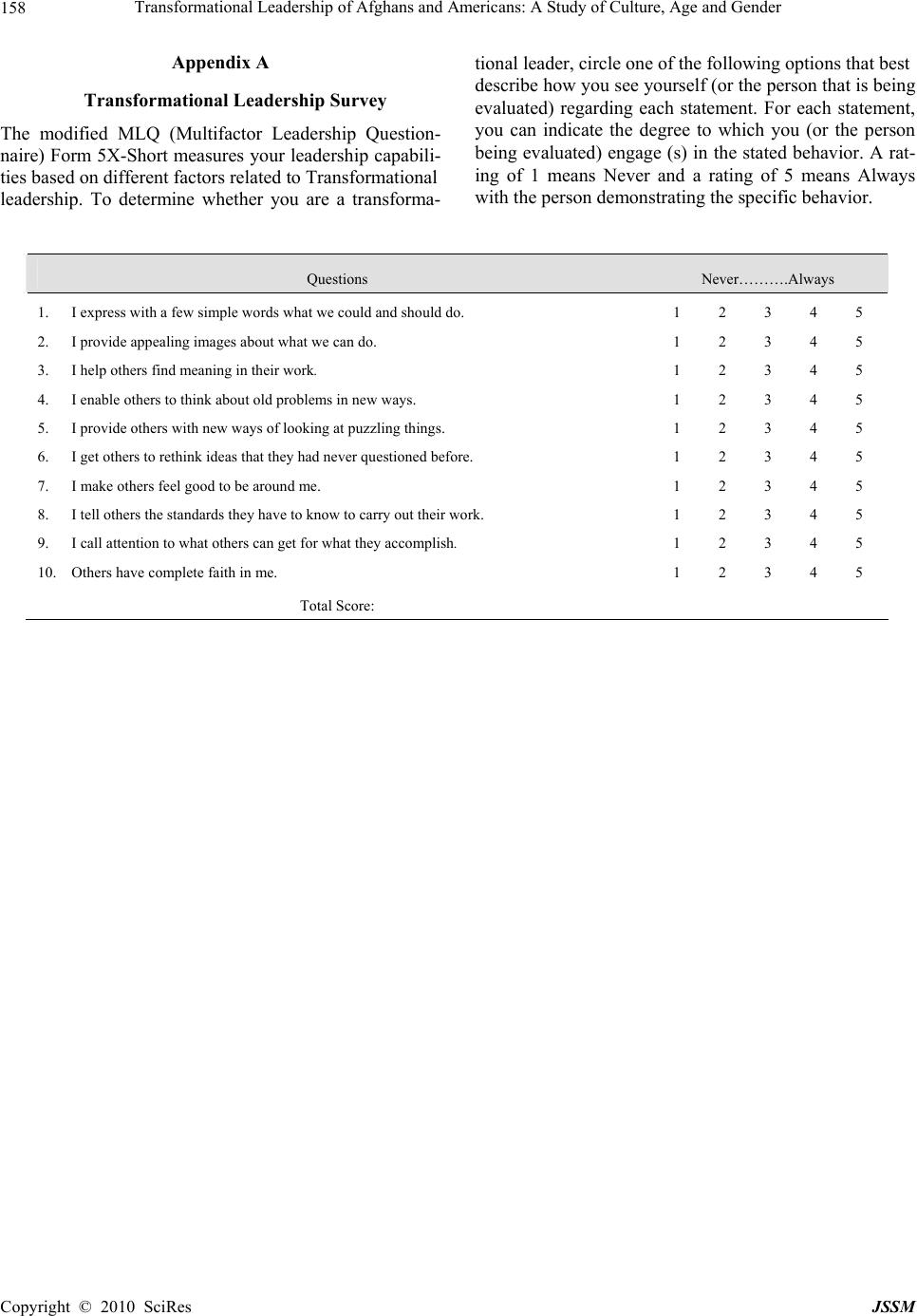

J. Service Science & Management, 2010, 3: 150-158 doi:10.4236/jssm.2010.31019 Published Online March 2010 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/jssm) Copyright © 2010 SciRes JSSM Transformational Leadership of Afghans and Americans: A Study of Culture, Age and Gender Belal A. Kaifi1 , Bahaudin G. Mujtaba2 1Franklin University, Columbus, USA; 2Nova Southeastern University, Fort Lauderdale, USA. Email: belalkaifi@yahoo.com, mujtaba@nova.edu Received October 22nd, 2009; revised November 29th; accepted January 3rd, 2010. ABSTRACT Afghans and Americans have been exposed to different leadership styles which may have influ enced their orientation on leading others. Age, gender, and/or culture are possible factors for such differences in leadership orientations. This research surveyed the responses of 502 Americans and 300 Afghans to better understand their orientation toward transformational leadership. The Afghan respondents had significantly higher scores for transformational leadership orientation. Female American respond en ts had a sign ifica ntly h igher transfo rmationa l leadership orienta tion than their Afghan female colleagues. Younger Afghans had a significantly higher tendency toward a transformational leadership orientation than their American counterparts. Suggestions for managers and implications for future research are presented. Keywords: Afghans, Americans, Afghanistan, Gender, Age, Culture, Leadership, Ethics 1. Introduction Culture, age group, and gender may influence a person’s leadership style and overall change management ap- proach. Leaders must believe in change in order for there to be a better future for a society or organization. “In highly competitive, rapidly changing environments, car- ing and appreciative leaders are the ones to bet on for long-term success” [1]. The 21st century leader must be equipped with the right tools to be effective, empathic, and efficient in all aspects of the workplace. Today’s competitive workplace requires more transformational leaders as they tend to influence workers more positively. Rhodes, Walsh, and Lok state, “While leaders initiate and drive organizational change, they manage the change only with the help of other change agents. These change agents operate with different change skills and compe- tencies depending on particular requirements and cir- cumstances” [2]. Pounder explains that the effect of transformational leadership on subordinates centers on three leadership outcomes: a) the ability of the leader to generate extra effort on the part of those being led, b) subordinates’ perception of leader effectiveness, and c) their satisfaction with the leader [3]. Furthermore, “Bass and his associates’ views on morality relative to trans- formational and transactional leadership do suggest that transactional leaders would be expected to engage in unethical practices more so than transformational lead- ers,” and further state that “Judgments of a leader’s ethi- cal posture may play a particularly strong role in influ- encing follower satisfaction with the leader” [4]. Franken, Edwards, and Lambert explain how “Business leaders are under constant pressure to comply with their demands while maintaining the organization’s competitiveness in increasingly complex markets” [5]. Transformational leaders are expected to not only to control, lead, plan, and organize, but also motivate, empower, and build healthy relationships with their peers throughout an or- ganization. A study by Mujtaba and Kaifi illuminated how Afghan leaders have higher scores on the relationship orientation which relates to better job performance [6]. The skills of building and maintaining a healthy relationship is an im- portant element of not just performance but also trans- formational leadership, especially when one has to create a win-win relationship between employees, vendors, and other stakeholders in the community or local govern- ments. “Over the last decade, considerable research effort has been invested into understanding the processes through which transformational leadership positively relates to follower attitudes, behavior, and performance” [7]. When exploring the conditions under which trans- formational leadership weaves its effects on performance, research results show that transformational leadership relates to follower identification with work unit and self-efficacy, to predict individual performance, thus representing a moderated mediation effect [7]. Another  Transformational Leadership of Afghans and Americans: A Study of Culture, Age and Gender Copyright © 2010 SciRes JSSM 151 study demonstrated “that instructors displaying transfor- mational leadership qualities in the classroom had a pos i- tive and significant influence on student perception of classroom dynamics measured in terms of the three lead- ership outcomes: extra effort, effectiveness, and satisfac- tion” [3]. The results appear to be consistent with other findings on transformational leadership which suggest that employees view this style “positively in terms of effectiveness, satisfaction, and motivation to expend ef- fort” [3]. Other researchers argue that “the proposed as- sociation of transformational and transactional leadership has been one of augmentation. The augmentation hy- pothesis argues that transformational leadership will sig- nificantly predict leadership criteria after controlling for transactional leadership ” [4]. Of course, effective leaders use a variety of methods to influence their followers and some researchers claim that “employees with higher lev- els of power distance orientation are less likely to be in- fluenced by transformational leadership behaviors alone and may instead ne ed to be led via d ifferent or additional leadership styles” [8]. Kirkman et al., further state that “individual-level cultural value orientations, and particu- larly power distance orientation, should not be ignored in studies of the impact of transformational leadership on followers across cultures” [8]. This study focuses on the leadership style of people in Afghanistan and the United States because an individual’s culture might very well be a factor in their influencing style. In both cultures, fol- lowers respect managers who are perceived to be just, fair, and ethical. Leaders who do the right thing are able to enhance the morale of their employees because all individuals want to be associated with good causes and institutions that take society’s needs into consideration. Transformational leaders must have an ethical intention in order to be followed and respected. Ricoeur states, “Let us define ‘ethical intention’ as aiming at the ‘good life’ with and for others, in just in- stitutions” [9]. The ethical intention is what transforma- tional leaders strive for in organizations of the 21st cen- tury because in order for an organization to be successful, there must be unity and collectivity along with just prac- tices. When aiming at the good life, leaders must con- sider not only themselves but how each person can make a difference by being more understanding, ethical, and concerned for th e welfare of all people within an org ani- zation. Ricoeur explains, “the good is not contained in any particular thing. The good is rather that which is lacking in all things. This ethics in its entirety presup- poses this nonsaturable use of the word predicate good” [9]. Ricoeur recognizes the importance of being ethical and the positive implications it has on daily actions of an organization. In an organization, every conversation can be meaningful, and may bring one that much closer to a good life by learning about the other. Ricoeur states, “To narrate and to follow a story is already to ‘reflect upon’ events with the aim of encompassing them in successive totalities” [10]. Being able to listen, understand, and communicate to a colleague is important for a transfor- mational leader and will benefit an organization by building trust, friendships, awareness, and respect. As Ricoeur explains, “the good life is for each of us, the nebulus of ideals and dreams of achievements with re- gard to which a life is held to be more or less fulfilled or unfilled” [9]. In organizations, transformational leaders need to understand others by focusing on solicitude, building friendships, and emphasizing equality because Ricoeur explains, “equality, however it is modulated, is to life in institutions what solicitude is to interpersonal relations” [9]. By having an ethical intention, a transfor- mational leader is able to lead by example. While the controversy regarding whether leaders are products of nature or nurture continue to live on, one element that is clear is how all people are influenced by their specific culture, age group, and gender. 2. Leadership and Culture Culture, or the w ay people behave in an organization can influence how a leader evaluates performance. Rhodes, Walsh, and Lok state that the “development of a high-performance culture requires the inspiration, drive, and commitmen t of the lead er, leadersh ip is critical to the change process underpinning the Balanced Scorecard” [2]. Furthermore, according to these authors, cultural values tend to have important implications on manage- ment practices, because “there is a positive relationship between a high performance culture and the adoption of best practices” [2]. For example, the United States’ cul- ture is considered to be high performance and, if organi- zations are to remain competitive, they must adopt best practices from around the globe. Some of these best practices may include the training and development of effective ethical leaders through succession planning and development because effective leaders require vision, knowledge, and execution skills. Leaders come in many shapes, forms, and styles which is why transformational leadership has been studied over the years. For example, Kim claims that “there may be at least two different leadership styles in groupthink: the lack of impartial leadership and laissez-faire” [11]. Oth- ers state that “In combination with the provision of autonomy, the team leader functions as a supportive member” [12]. Kaifi explains how a transformation leader should consider “the primary tasks of the organi- zation by figuring out the most efficient, effective, and productive way to complete all tasks [13]. Daniel and Davis emphasize that “Managers who lead high-per- formance teams in highly competitive industries must  Transformational Leadership of Afghans and Americans: A Study of Culture, Age and Gender Copyright © 2010 SciRes JSSM 152 balance complex interpersonal relationships with corpo- rate deadlines” [14]. Teamwork is critical for success in the modern workplace because fast and effective solu- tions to conundrums require the creativity and talents of all stakeholders. According to Pryor et al., “It is impera- tive that managers, team leaders, and team members un- derstand the elements required for team success and the potential for team failure” [15]. Kearney proposes that transformational leadership in the modern workplace “will engender positive effects on team performance only to the extent that the team members regard it as legiti- mate and appropriate that one person among them, the leader, occupies a p rivileged p osition” [1 6]. As su ch, this study proposes the following hypothesis: Hypothesis 1 – Afghans and Americans will have similar transformational leadership scores. 3. Leadership and Gender Males and females may lead from different perspectives and these diverse leadership perspectives can lead to dif- ferent approaches to problem-solving. “Current psycho- logical research on leadership and team interaction sug- gests that men and women exhibit different leadership styles and interpersonal communication styles in a vari- ety of small-group situations from student problem- solving situations to industry and community situations” [17]. Lantz writes that “women executives are much more likely than males to be a department head or to fill some other staff position, whereas men are much more likely to be chief executive officer (CEO), chief operat- ing officer (COO), president, or vice president” [18]. Many believe that the glass ceiling phenomenon contin- ues to play a role in today’s workforce. For example, Babcock explains that “Rather than intentional acts of bias, second-generation gender biases reflect the con- tinuing dominance of traditionally masculine values in the workplace” [19]. Women are perceived to be too emotional and less competitive than men. For example, some authors have written that “Women are significantly more risk averse, tend to be less overconfident and be- have less competitiv ely oriented” [20]. Overall, th ere is a disparity between the equal promotion of men and women to higher positions: “Despite high-profile success stories of female CEOs such as Meg Whitman of eBay, only a handful of Fortune 500 firms in 2008 have a woman in the top spot. Consequently, concern remains about the progress women are making” [21]. Some of the biases are very subtle and not necessarily as blatant as they used to be, which may be a result of human resource professionals doing a more effective and meticulous job of making their managers aware of the existing equal opportunity employment laws in th e United States. How- ever, “Workplace inflexibilities and lack of organiza- tional support are driving women away, creating a leaky pipeline of female talent” [22]. If there are biases in the promotion of female candidates, there will be fewer role models for others to follow who are interested in follow- ing in their footsteps. This phenomenon is likely to be just as true in Afghanistan as it is in the United States. “In gender studies of public administration, there is sig- nificant evidence that women have less organizational power than men, measured in lower pay, fewer career opportunities, and underrepresentation at the highest leadership levels” [23]. As such, this study proposes the following hypotheses: Hypothesis 2 – Afghan and American males will have similar transformational leadership scores. Hypothesis 3 – Afghan and American females will have similar transformational leadership scores. 4. Leadership and Perceptions of Age Leaders and styles of leadership may vary based upon age groups. Some authors have written that “With an older leader, the team may be more open to a leader’s transformational behaviours, because the team members may be more accepting of the leader’s special status” [16]. Kearney further comments that: Results indicate that it makes a difference whether transformational lead- ership is provided by a leader who is older than or about the same age as the followers. Only in the former case was there a positive relationship between transforma- tional leadership and team performance. Moreover, the data yielded no eviden ce for a curvilin ear effect. [16]. According to Van Vugt, “Age relates to leadership in a complicated way, according to the psychological litera- ture. Some research finds a positive correlation between age and leadership, whereas others find a zero or nega- tive correlation” [24]. Age makes a difference if the leader is respected for his or her knowledge, expertise, overall wisdom, and communication or listening skills. For example, “Experience in Britain suggests that there is a growing confidence that an effective coach working with senior people can achieve positive results, provided he or she has the ability to listen” [25]. Leaders must demonstrate that they are intelligen t and capable of mak- ing decisions: The evolutionary game model also sug- gests that people who are quicker to recognize a situation as a coordination problem, that requires leadership, emerge as leaders more often. Furthermore, they must convince people that following is the best option. From this, I expect that leadership correlates with intelligence, because it helps in identifying coordination problems as well as in coordinating actions of multi ple actors [24] . Besides making intelligent personal and professional decisions, it is also important for younger and older leaders to be seen as generous and fair as “leadership is correlated with traits and behaviors that signal generosity and fairness” [24]. The theory of moral development states that as individuals’ age, they are likely to gain more knowledge about right and wrong and fairness. So  Transformational Leadership of Afghans and Americans: A Study of Culture, Age and Gender Copyright © 2010 SciRes JSSM 153 age has positively contributed to wisdom and knowledge of human beings since individuals are able to learn from personal experiences and the observation of others, and ultimately make positive changes to their habits and behaviors. Van Vugt explains that: In ancestral envi- ronments, some situations required the possession of unique and specialized knowledge, for example, where to find a waterhole that has no t yet dried up. Know ledge about where to go would have been more likely to be held by older and experienced individuals, and, thus leading is expected to correlate positively with age in this domain. In the present time, evidence for this link between age and leadership can still be found in profes- sions that require a considerable amount of specialized knowledge and experience, such as in science, politics, and arts [24]. Of course, “workforce ag ing is not a new phenomenon, its confluence with o ther factors such as early retirement programmes and decreased supplies of skilled craft workers appears to be giving the problem an unprece- dented significance” [26]. As such, this study proposes the following hypotheses: Hypothesis 4 – Afghan and American respondents who are 26 years of age and older will have similar transfor- mational leadership scor es. Hypothesis 5 – Afghan and American respondents who are 25 years of age and younger will have similar trans- formational leadership scores. 5. Research Methodology Afghans and Americans who participated in this study completed a modified MLQ 5X-Short (Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire) survey that was originally developed by Bass and Avolio for leadership studies. The survey instrument used for this study had eleven short questions (see Appendix A) designed for the population. Many transformational leadership research- ers (Pounder, 2008; Kearney, 2008; Ling et al., 2008; and Jansen et al., 2008) have used similar instruments to study the leadership styles of various participants. For example, Pounder used a modified version of the MLQ Form 5X-Short which “involved a sample of in- structors and undergraduate students in a Hong Kong university business school [3]. Pounder used a version of the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire that was modified for a classroom situation to better understand the styles of prospective leaders. The survey questions were set up in a Likert scale for- mat wher e a r esp ons e of 1 me an s “N eve r” and a r espons e of 5 means the element is “Always” a characteristic of the responder. One of the questions in the survey asked the respondent the following: “I express with a few sim- ple words what we could an d should do”, and a differen t question asked, “I provide others with new ways of looking at puzzling things.” The respondent would rate him or herself from a scale of 1 to 5 in regard to how many words he or she might use to actually express his or her views. The higher the overall mean scores, the more chances that he or she is likely to have a stronger orientation toward a transformational leadership style. One’s range for being a transformational leader can be expressed with a score of “V ery low” to a score of “Very high” as presented in Table 1. The survey instrument was distributed to 2,000 Af- ghans and Americans by using Facebook as a so- cial-networking instrument to get good participation. A total of 300 surveys were completed successfully by Af- ghans who live throughou t the United States and abroad. Furthermore, a total of 502 surveys were completed suc- cessfully by American respondents from the United States. So a total of 802 responses, which represents a 45% response rate, were used for analysis. The research question for this study is: Do Afghans and Americans have similar or differen t transforma tion al leadership scores? For this survey, the higher the overall sum of the scores, the more likely that the participant is strongly oriented toward a transformational leadership style. 6. Results and Analysis The responses of 802 Afghans and Americans demon- strate that there is a statistically significant difference in their mean transformational leadership scores (t = 7.83; p < 0.001), as presented in Table 2. Afghan respondents have a significantly higher score on transformational leadership, which means that the first hypothesis, “Afghans and Americans will have similar transformational lead- ership scores,” cannot be supported. While the mean score of Afghan respondents fall in the high range, the American respondents mean score falls in the moderately high range for transformational leadership orientation. Table 1. Transformational leadership orientation range 45–50 Very high range 40–44 High range 35–39 Moderately high range 30–34 Moderately low range 25–29 Low range 10–24 Very low range Table 2. Transformational leadership score by culture de- scriptive statistics and T-test of two means Culture Mean Standard Deviation Sample Size Afghan 41.266* 4.26 300 American 39.6096* 1.612 502 * t = 7.83; p < 0.001  Transformational Leadership of Afghans and Americans: A Study of Culture, Age and Gender Copyright © 2010 SciRes JSSM 154 The second hypothesis predicted that “Afghan and American males will have similar transformational lead- ership scores” and, as presented in Table 3, this study could not support this suppo sition because male Afghans have a significantly higher score than their American counterparts. The third hypothesis predicted that “Afghan and American females will have similar transformational leadership scores” and, as presented in Table 4, this study could not support this supposition because Ameri- can females’ mean score is significantly higher than their female Afghan counterparts. The fourth hypothesis predicted that “Afghan and American respondents who are 26 years of age and older will have similar transformational leadership scores” and, as presented in Table 5, this study could not support this supposition because older Americans have a signifi- cantly higher score than their Afghan colleagues. The last hypothesis predicted that “Afghan and American respondents who are 25 years of age and younger will have similar transformational leadership scores” and, as presented in Tab le 6, th is study could not support this supposition because the scores are signifi- cantly different. Younger Afghans have a significantly higher transformational leadership score than their American colleagues. Table 3. Transformational leadership score of males de- scriptive statistics and T-test of two means Males Mean Standard Deviation Sample Size Afghan Males 44.7933 2.18689 150 American Males 39.54 1.75 280 t = 27.2; p < 0.001 Table 4. Transformational leadership score of females de- scriptive statistics and T-test of two means Females Mean Standard Deviation Sample Size Afghan Females 37.74 2.56049 150 American Females 39.7 1.41 222 t = –9.48; p < 0.001 Table 5. Transformational leadership score by age descrip- tive Statistics and T-test of two means Age Mean Standard Deviation Sample Size Older Afghans 37.36 2.097 50 Older Americans 39.59 1.64 302 t = –8.53; p < 0.001 Table 6. Transformational leadership score by age descrip- tive statistics and T-test of two means Age Mean Standard Deviation Sample Size Younger Afghans 42.048 4.15 250 Younger Americans39.645 1.57 200 t = 7.99; p < 0.001 This study has demonstrated that Afghans and Ameri- cans have significantly different transformational lead- ership scores. The Afghan respondents scored in the higher range for having a transformational leadership orientation. This finding corroborates Kaifi’s study which explains how most Afghans are natural transfor- mational leaders partly because they have been influ- enced by leaders who have fought for reform, moderni- zation, and a prosperous vision for Afghanistan [27]. Furthermore, there was a statistically significant differ- ence between the scores of Afghans and Americans based on gender and age. Female American respondents as well as older American respondents had a significantly higher transformational leadership orientation than their Afghan colleagues. Younger Afghan respondents as well as male Afghans had a significantly higher tendency to- ward a transformational leadership orientation than their American counterparts. 7. Implications of the Study This study has demonstrated that Afghans seem to be naturally oriented toward transformational leadership tendencies. From an ideo logical perspective, Afghans are inclined to be transformational leaders because the Afghan culture places a considerable emphasis on respecting elders because of their knowledge, wisdom, and experi- ence, which explains why older transformational leaders are usually more successful in influencing the Afghan population. This research has shown that young Afghan respondents are even more inclined to be transforma- tional leaders than their older counterparts. Global busi- ness and human resource management practices can be challenging when an organization is working with people of a different culture [28]. Organizations that are inter- ested in conducting business in Afghanistan or around the globe should feel confident in hiring an Afghan to lead the organization, which contradicts the current frame of thought. Due to societal conditioning and cross-cultural ten- dencies of human nature, some managers assume that employees from high-context cultures such as Afghani- stan are likely to be more relationship-oriented which may distract employees from not completing their tasks in a timely manner. For example, they may not be asser- tive enough to pressure their peers toward being more productive when there is a backlog or even to ask for  Transformational Leadership of Afghans and Americans: A Study of Culture, Age and Gender Copyright © 2010 SciRes JSSM 155 help when necessary because they do not want to appear “pushy” or “rude.” Of course, such assumptions are often wrong as the Afghan respondents in this survey have higher transformational leadership scores when com- pared to their American counterparts. These results are important elements for multinational managers, administrators of USAID (the United States of America’s International Development) agency, NGOs (non-governmental agencies), and other contractors re- cruiting professionals for jobs and assignments in and around Afghanistan. As a matter of fact, “Afghan leaders from all professions have started emerging. There are currently many Afghan-American medical doctors, en- gineers, attorneys, professors, police officers, and many who work in either the private or public sectors of the workforce” [29]. The modern workplace for a multina- tional firm can be very diverse as the workforce today is filled with people from many different leadership styles. Kaifi explains how using multiple frames to evaluate an organization will help a transformational leader under- stand complex issues within an organization and will result in continuous improvements [13]. As such, “ad- ministrators must be managers of diverse interests” and “this necessity grows out of the relativity of values and the pluralization of society” [30]. Managers should pro- vide a better understanding of their rules and policies along with diversity education for all their employees [31]. It is for certain that Afghans and Afghan-Americans bring diverse views and perspectives with an orientation toward transformational leadership into the workplace which can help make them ethical and respected leaders within their teams, departments, organizations, and com- munities. In all organizations, there is a high-demand for trans- formational leaders because of organizational changes due to technology, globalization, and competition. For example, radiology departments throughout America have implemented digital technology (digital images) that has replaced the analog technology (x-rays). During this organizational change, transformational leaders were tasked with successfully implementing this new technol- ogy which is why “organizations are quick to look for leaders who are great communicators, visionary thinkers, and who can also get things done and follow through” [32]. It is important for a transformational leader to first understand the organizational culture and gain the trust of subordinates in order to effectively reframe, imple- ment new strategies, and transform an organization to be able to compete in today’s global economy. A research study by Morhart, Herzog and Tomczak suggests “that managers should make a paradigm shift from a TRL [transactional leadership] to a TFL [trans- formational leadership] philosophy” and go on to say, “At first glance, specifying behavioral codices and scripts for employees dealing with customers and then monitoring and rewarding appropriate demeanor might seem to be an easy solution for obtaining adequate per- formance from employees representing the corporate brand” [33]. They further mention that: However, we found that a highly transactional style was counterproductive in terms of followers’ motiva- tional condition. Managers would do much better by opening their minds to a TFL approach, which would entail behaviors such as articulating a unifying brand vision, acting as an appropriate role model by living the brand values, giving followers freedom to individually interpret their roles as brand representatives, and provid- ing individualized support by acting as a coach and mentor. This would allow followers to experience the feelings of relatedness, autonomy, and competence in their roles as brand representatives, which would ulti- mately spill over into the commitment, authenticity, and proactivity that characterize a real brand champion [33]. While transactional leadership styles might be appro- priate for specific organizations and situations such as in hospitals experiencing technological changes, this style is usually effective only in the short-term and may not serve a developmental objective. As such, transforma- tional leadership is usually the best alternative for long-term success in employee development situations and when one is trying to inspire and motivate. Research shows that “although employees were more likely to have higher levels of power distance orientation in the PRC [People’s Republic of China] than in the U.S., indi- viduals in both countries reacted differently to transfor- mational leadership on the basis of their individual power distance orientation” and furthermore, “irrespective of country-level cultural variation, transformational leader- ship is especially important for managers whose em- ployees have a low power distance orientation” [8]. A different study explains that, “to be effective, transfor- mational leaders must develop high quality leader-fol- lower relationships, both LMX [Leader-Member Ex- change] and interactional justice, with followers. In this sense, leaders must treat followers with kindness and fairness, develop meaningful social exchange relation- ships (e.g., trust, professional respect) with them, and maintain equitable exchanges with them” [34]. Justice, fairness and good ethical values are important for all leaders, regardless of their cultural orientation. In a highly just and ethical environment, employees will be more committed and motivate d to do what is right for the company and their customers. Fisher explains that “Transformational leadership goes beyond the idea that workers are motivated by rewards and punishments by considering other motivators for effective performance” [35]. Transformational leaders must also create an or- ganizational culture where people feel free to think, dis- cuss and express their new ideas. Furthermore, in such an environment:  Transformational Leadership of Afghans and Americans: A Study of Culture, Age and Gender Copyright © 2010 SciRes JSSM 156 Managers need to be mindful that selecting employees on the basis of their learning orientation alone will not guarantee creativity. It is building the creative self- efficacy of their employees that will provide the facili- tating conditions for the learning orientation to take hold and bring forth creativity. Managers can be instrumental here in terms of providing an environment that stimulates and nourishes creative self-efficacy, through, for exam- ple, applying transformational leadership principles [36]. The 21st century requires tr ansformational leaders who are able to help organizations thrive, continuously im- prove, and accomplish its goals. 8. Limitations of the Study There are some limitations to this study and one is the modified MLQ 5X-Short (Multifactor Leadership Ques- tionnaire) survey used for this research. This short survey can be combined with other more comprehensive instru- ments to enhance and confirm the results. Future studies can duplicate the research with a greater number of Af- ghan participants that are compared to other ethnicities. The fact that this study was conducted with a convenient sample population, living in urban areas and included expatriate Afghans living outside of Afghanistan, was a further limitation. This point is particularly important for the Afghan respondents, who consequently, may have become more “westernized” as a result of living and working in foreign locations. Future studies might con- trol this variable by expanding the research population to include respondents from within Afghanistan. Finally, future researchers should consider translating the survey instru men t in to Per sian and Pa sh to lan gu ag es so as to f ac ili- tate the test subjects’ preferred and dominant reading skills. 9. Conclusions This study focused on the Afghan and American popula- tion to compare and better understand their transforma tional leadership tendencies. The premise of the study was to determine if Afghans and Americans have similar transformational leadership scores and this study has confirmed that their scores are significantly different in regard to culture, age, and gender. From a cultural per- spective, the results demonstrated that the Afghan re- spondents scored in the high range and the Americans scored in moderately high range for transformational leadership orientation. From gender and age perspectives, female and older American respondents had a signifi- cantly higher transformationa l leadership orientation th an their Afghan colleagues. Younger, as well as male, Af- ghans had a significantly higher tendency toward a transformational leadership orientation than their Ameri- can counterparts. It is important for transformational leaders to under- stand the organizational culture, provide fair promotional opportunities for both males and females, remain ethical and expect high moral standards, respect people of all ages, and gain the trust of subordinates in order to suc- cessfully compete in today’s global economy. REFERENCES [1] J. M. Kouzes and B. Z. Posner, “Encouraging the heart,” Jossey-Ba ss, San Francisco, 2003. [2] J. Rhodes, P. Walsh, and P. Lok, “Convergence and di- vergence issues in strategic management – Indonesia’s experience with the balanced scorecard in HR manage- mentm,” The International Journal of Human resources Management, Vol. 19, No. 6, pp. 1170–1185, 2008. [3] J. Pounder, “Transformational leadership: Practicing what we teach in the Management classroom,” Journal of Edu- cation for Business, Vol. 84, No. 1, pp. 2–6, 2008. [4] R. Vecchio, J. Justin, and C. Pearce, “The utility of trans- actional and transformational leadership for predicting performance and satisfaction within a path-goal theory framework,” Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, Vol. 81, No. 1, pp. 71–82, 2008. [5] A. Franken, C. Edwards, and R. Lambert, “Executing strategic change: Understanding the critical management Elements that lead to success,” California Management Review, Vol. 51, No. 3, pp. 49–73, 2009. [6] B. G. Mujtaba and B. A. Kaifi, “Afghan and American professionals’ leadership orientation toward tasks and re- lationships: Are there tendencies toward convergence or divergence?” Fortune Journal of International Manage- ment, Vol. 5, No. 1, pp. 107–125, 2008. [7] F. Walumbwa, B. Avolio, and W. Zhu, “How transforma- tional leadership weaves its influence on individual job performance: The role of identification and efficacy be- liefs,” Personnel Psychology, Vol. 61, No. 4, pp. 793–825, 2008. [8] B. Kirkman, G. Chen, J. Farh, Z. Chen, and K. Lowe, “Individual power distance orientation and follower reac- tions to transformational leaders: A cross level, cross- cultural examination,” Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 52, No. 4, pp. 744–764, 2009. [9] P. Ricoeur, “Oneself as another,” University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1992. [10] P. Ricoeur, “The narrative function,” John B. Thompson, Ed., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 274– 296, 1982 [11] Y. Kim, “A comparative study of the ‘Abilene Paradox’ and ‘Groupthink’,” Public Administration Quarterly, Vol. 25, No. 2, pp. 168–189, 2001. [12] A. Laszlo, K. Laszlo, and C. Johnsen, “From high-per- formance teams to evolutionary learning communities: New pathways in organizational development,” Journal of Organizational Transformation and Social Change, Vol. 6, No. 1, pp. 29–48, 2009. [13] B. A. Kaifi, “21st century leadership in healthcare,” Chap- ter Twelve in the Pharmaceutical Technician Laboratory Manual by Sandeep Bansal, Jones and Bartlett Publica- tions, Boston, Massachusetts, pp. 90–100, 2009  Transformational Leadership of Afghans and Americans: A Study of Culture, Age and Gender Copyright © 2010 SciRes JSSM 157 [14] L. Daniel and C. Davis, “What makes high-performance teams excel?” Research Technology Management, Vol. 52, No. 4, pp. 40–45, 2009. [15] M. Pryor, L. Singleton, S. Taneja, and L. Toombs, “Te am- ing as a strategic and tactical tool: An analysis with rec- ommendations,” International Journal of Management, Vol. 26, No. 2, pp. 320–333, 2009. [16] E. Kearney, “Age differences between leader and follow- ers as a moderator of the relationship between transfor- mational leadership and team performance,” Journal of Occupational & Organizational Psychology, Vol. 81, No. 4, pp. 803–811, 2008. [17] J. Winter, J. Neal, and K. Wa ne r, “How mal e , femal e, a nd mixed-gender groups regard interaction and leadership differences in the business communication course,” Busi- ness Communication Quarterly, Vol. 64, No. 3, pp. 43–58. 2001. [18] P. Lantz, “Gender and leadership in healthcare admini- stration: 21st century progress and challenges,” Journal of Healthcare Management, Vol. 53, No. 5, pp. 291–301. 2008. [19] L. Babcock, “What happens when women don’t ask?” Negotiation, Vol. 11, No. 96, pp. 1–4, 2008. [20] D. Beckman and L. Menkhoff, “Will women be women? Analyzing the gender difference among financial ex- perts,” Kyklos, Vol. 61, No. 3, pp. 364–384, 2008. [21] D. Wyld, “How do women fare when the promotion rules change?” Academy of Management Perspectives, Vol. 22, No. 4, pp. 83–85, 2008. [22] E. Cabrera, “Fixing the leaky pipeline: Five ways to retain female talent,” People and Strategy, Vol. 32, No. 1, pp. 40–45, 2009. [23] S. Portillo and L. Dehart-Davis, “Gender and organiza- tional rule abidance,” Public Administration Review, Vol. 69, No. 2, pp. 339–347, 2009. [24] M. Van Vugt, “Evolutionary origins of leadership and followership,” Personality& Social Psychology Review, Vol. 10, No. 4, pp. 354–371, 2006. [25] W. Altman, “Executive coaching comes of age,” Engi- neering Management, Vol. 17, No. 5, pp. 26–29, 2007. [26] M. Ashworth, “Preserving knowledge legacies: workforce aging, turnover and human resource issues in the US electric power industry,” International Journal of Human Resource Management, Vol. 17, No. 9, pp. 1659–1688, 2006. [27] B. A. Kaifi, “A transformational leader,” Sitara Magazine, Vol. 1, No. 4, pp. 48–50, 2008. [28] G. Karadjova-Stoev and B. G. Mujtaba, “Strategic human resource management and global expansion lessons from the Euro disney challenges in France,” International Busi- ness and Economics Research Journal, Vol. 8, No. 1, pp. 69–78, 2009. [29] B. A. Kaifi, “The impact of 9/11 on Afghan-American leaders,” Xlibris, Bloomington, 2009. [30] T. Cooper, “The responsible administrator (4th ed.),” Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA, 1998. [31] B. A. Kaifi and B. G. Mujtaba, “Workforce discrimina- tion: An inquiry on the perspectives of Afghan-American professionals,” Journal of Business Studies Quarterly, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 1–15, 2009. [32] T. Rath and B. Conchie, “Strengths based leadership,” Gallup Press, NY, 2009. [33] F. Morhart, W. Herzog, and T. Tomczak, “Brand-specific leadership: Turning employees into brand champions,” Journal of Marketing, Vol. 73, No. 5, pp. 122–142, 2009. [34] M. Carter, A. Jones-Farmer, A. Armenakis, H. Field, and D. Svyantek, “Transformational leadership and followers’ per- formance: Joint mediating effects of leader-member ex- change and interactional justice,” Academy of Management Conference Proceedings, Chicago, United States, 2009. [35] E. Fisher, “Motivation and leadership in social work man- agement: A revi ew of theories and related studie s,” Admini- stration in Social Work, Vol. 33, No. 4, pp. 347–367, 2009. [36] Y. Gong, J. Haung, and J. Farh, “Employee learning ori- entation, transformational leadership, and employee crea- tivity: The mediating role of employee creative self-effi- cacy,” Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 52, No. 4, pp. 7765–7778. 2009  Transformational Leadership of Afghans and Americans: A Study of Culture, Age and Gender Copyright © 2010 SciRes JSSM 158 Appendix A Transformational Leadership Survey The modified MLQ (Multifactor Leadership Question- naire) Form 5X-Short measures your leadership capabili- ties based on different factors related to Transformational leadership. To determine whether you are a transforma- tional leader, circle one of the fo llowing options that best describe how you see yourself (or the person that is being evaluated) regarding each statement. For each statement, you can indicate the degree to which you (or the person being evaluated) engage (s) in the stated behavior. A rat- ing of 1 means Never and a rating of 5 means Always with the person demonstrating the specific behavior. Questions Never……….Always 1. I express with a few simple words what we could and should do. 2. I provide appealing images about what we can do. 3. I help others find meaning in their work. 4. I enable others to think about old problems in new ways. 5. I provide others with new ways of looking at puzzling things. 6. I get others to rethink ideas that they had never questioned before. 7. I make others feel good to be around me. 8. I tell others the standards they have to know to carry out their work. 9. I call attention to what others can get for what they accomplish. 10. Others have complete faith in me. 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 Total Score: |