Paper Menu >>

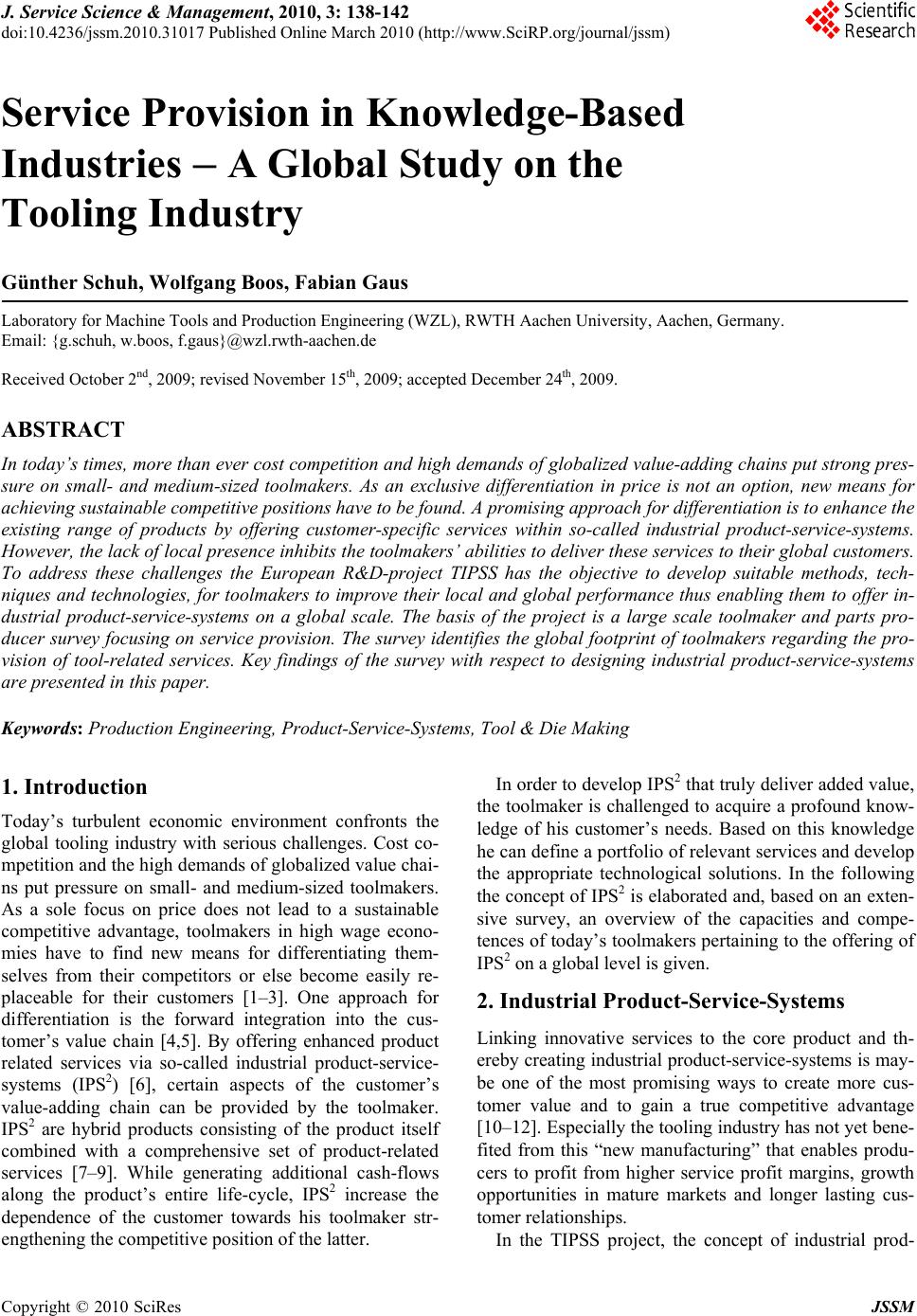

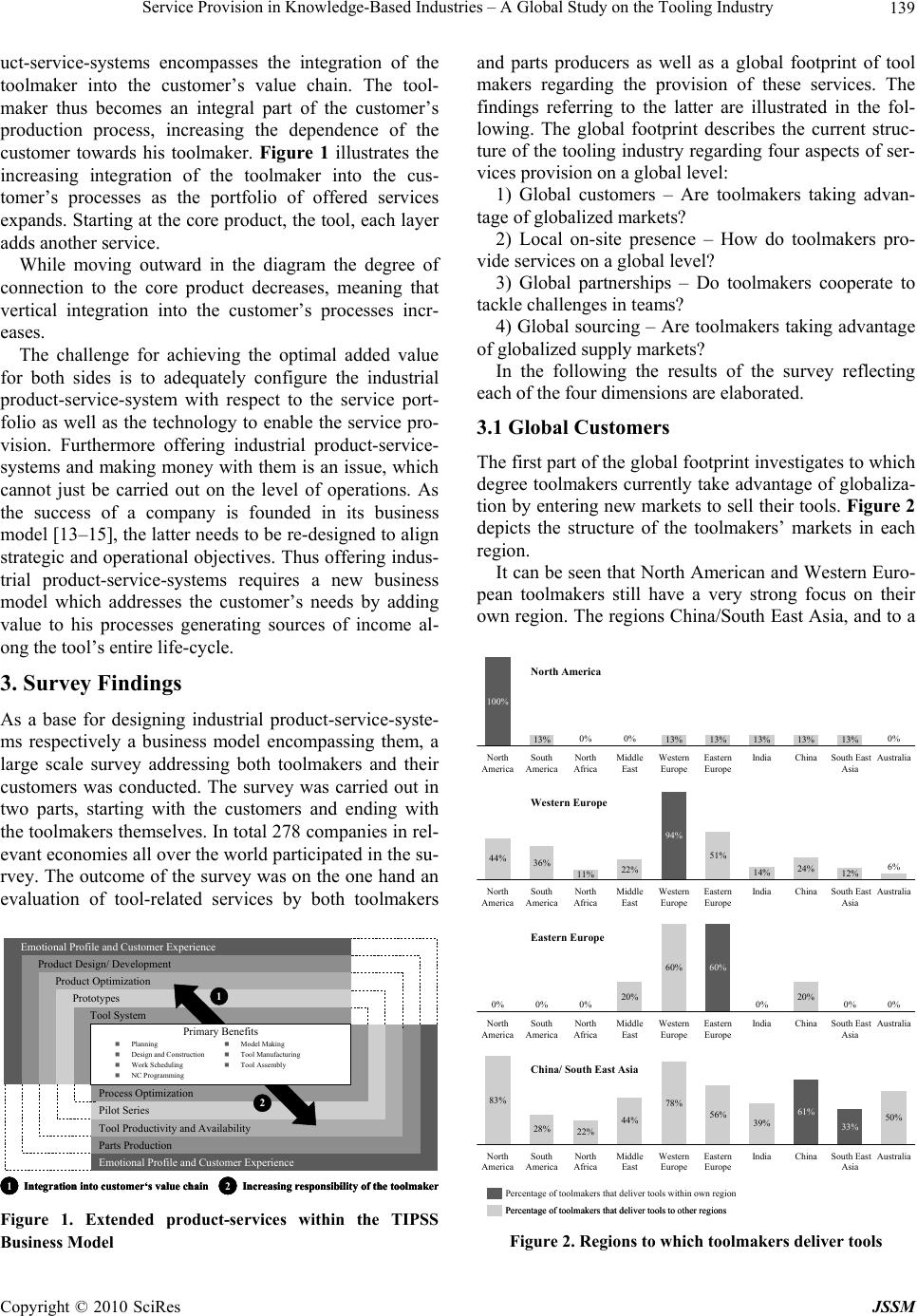

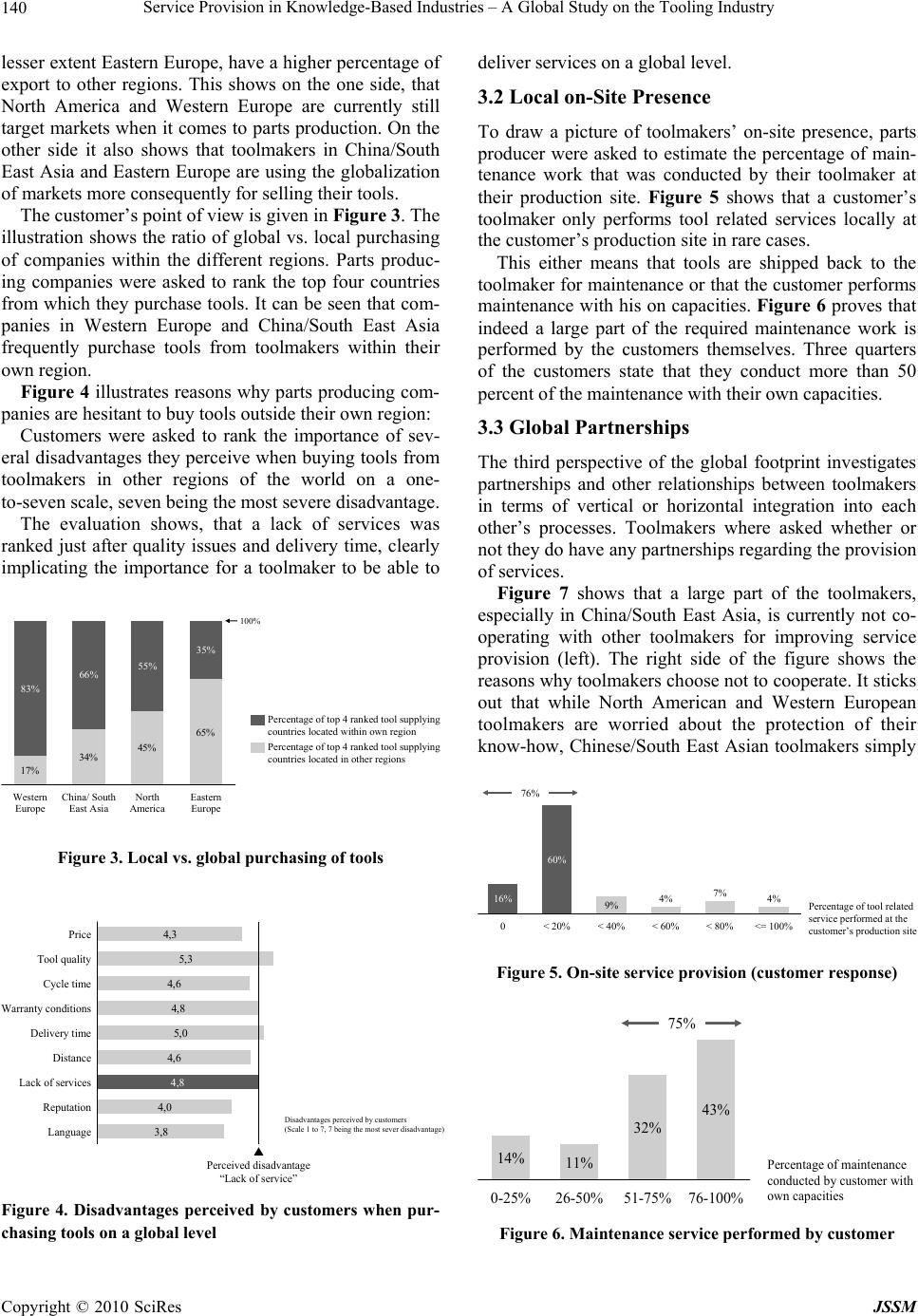

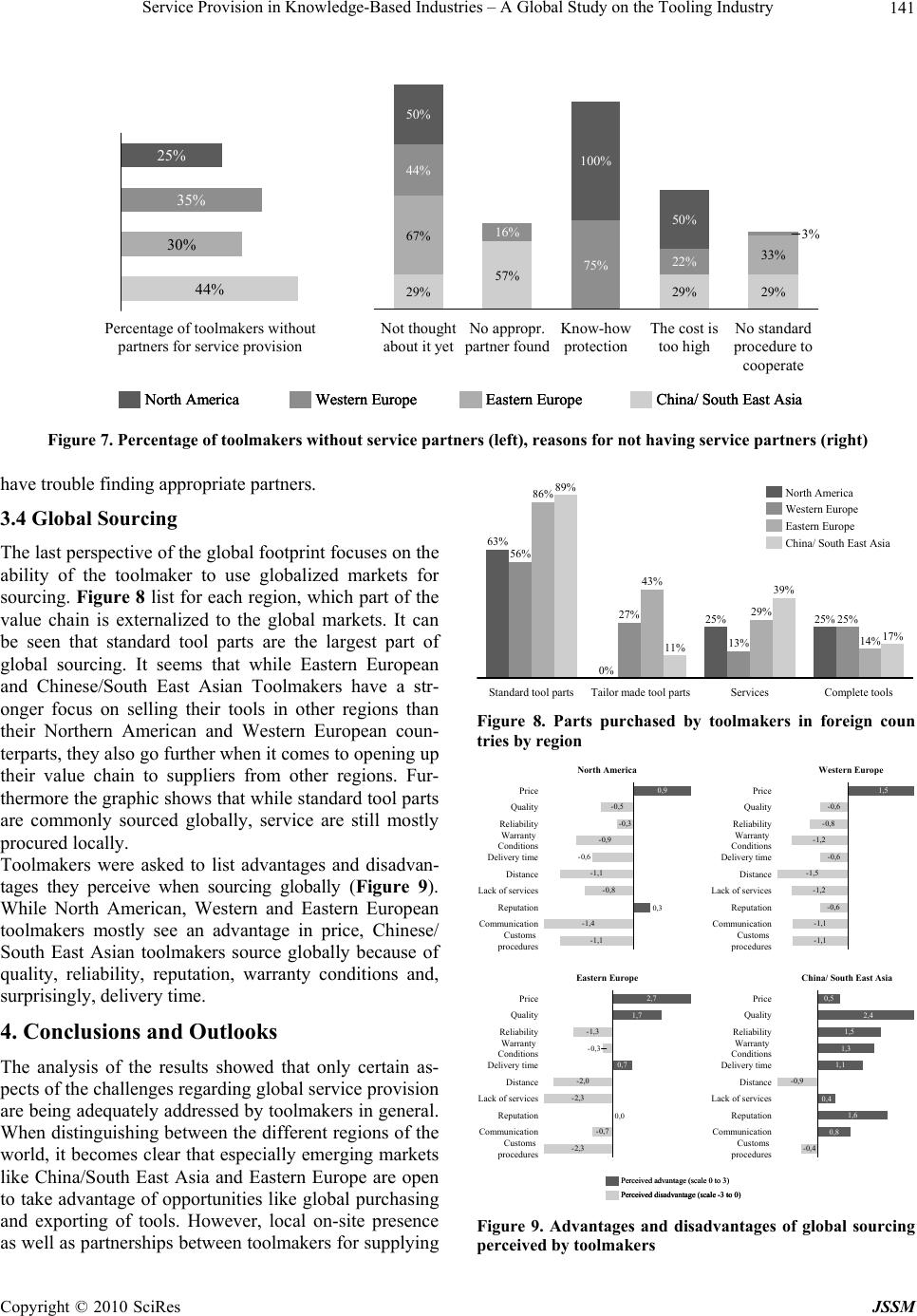

Journal Menu >>

J. Service Science & Management, 2010, 3: 138-142 doi:10.4236/jssm.2010.31017 Published Online March 2010 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/jssm) Copyright © 2010 SciRes JSSM Service Provision in Knowledge-Based Industries – A Global Study on the Tooling Industry Günther Schuh, Wolfgang Boos, Fabian Gaus Laboratory for Machine Tools and Production Engineering (WZL), RWTH Aachen University, Aachen, Germany. Email: {g.schuh, w.boos, f.gaus}@wzl.rwth-aachen.de Received October 2nd, 2009; revised November 15th, 2009; accepted December 24th, 2009. ABSTRACT In today’s times, more than ever cost competition and high demands o f globalized value-add ing cha ins put stron g pres- sure on small- and medium-sized toolmakers. As an exclusive differentiation in price is not an option, new means for achieving sustainable competitive positions have to be found. A promising approach for differentiation is to enhance the existing range of products by offering customer-specific services within so-called industrial product-service-systems. However, the lack of local presence inhibits the toolmakers’ abilities to deliver these services to their global customers. To address these challenges the European R&D-project TIPSS has the objective to develop suitable methods, tech- niques and technologies, for toolmakers to improve their local and global performance thus enabling them to offer in- dustrial product-service-systems on a global scale. The basis of the project is a large scale toolmaker and parts pro- ducer survey focusing on service provision. The survey identifies the global footprint of toolmakers regarding the pro- vision of tool-related services. Key findings of the survey with respect to designing industrial product-service-systems are presented in this paper. Keywords: Production Engineering, Product-Service-Systems, Tool & Die Making 1. Introduction Today’s turbulent economic environment confronts the global tooling industry with serious challenges. Cost co- mpetition and the high demands of globalized value chai- ns put pressure on small- and medium-sized toolmakers. As a sole focus on price does not lead to a sustainable competitive advantage, toolmakers in high wage econo- mies have to find new means for differentiating them- selves from their competitors or else become easily re- placeable for their customers [1–3]. One approach for differentiation is the forward integration into the cus- tomer’s value chain [4,5]. By offering enhanced product related services via so-called industrial product-service- systems (IPS2) [6], certain aspects of the customer’s value-adding chain can be provided by the toolmaker. IPS2 are hybrid products consisting of the product itself combined with a comprehensive set of product-related services [7–9]. While generating additional cash-flows along the product’s entire life-cycle, IPS2 increase the dependence of the customer towards his toolmaker str- engthening the competitive position of the latter. In order to develop IPS2 that truly deliver added value, the toolmaker is challenged to acquire a profound know- ledge of his customer’s needs. Based on this knowledge he can define a portfolio of relevant services and develop the appropriate technological solutions. In the following the concept of IPS2 is elaborated and, based on an exten- sive survey, an overview of the capacities and compe- tences of today’s toolmakers pertaining to the offering of IPS2 on a global level is given. 2. Industrial Product-Service-Systems Linking innovative services to the core product and th- ereby creating indu strial product-service-systems is may- be one of the most promising ways to create more cus- tomer value and to gain a true competitive advantage [10–12]. Especially the tooling industry has not yet bene- fited from this “new manufacturing” that enables produ- cers to profit from higher service profit margins, growth opportunities in mature markets and longer lasting cus- tomer relationships. In the TIPSS project, the concept of industrial prod-  Service Provision in Knowledge-Based Industries – A Global Study on the Tooling Industry Copyright © 2010 SciRes JSSM 139 uct-service-systems encompasses the integration of the toolmaker into the customer’s value chain. The tool- maker thus becomes an integral part of the customer’s production process, increasing the dependence of the customer towards his toolmaker. Figure 1 illustrates the increasing integration of the toolmaker into the cus- tomer’s processes as the portfolio of offered services expands. Starting at the core product, the tool, each layer adds another service. While moving outward in the diagram the degree of connection to the core product decreases, meaning that vertical integration into the customer’s processes incr- eases. The challenge for achieving the optimal added value for both sides is to adequately configure the industrial product-service-system with respect to the service port- folio as well as the technology to enable the service pro- vision. Furthermore offering industrial product-service- systems and making money with them is an issue, which cannot just be carried out on the level of operations. As the success of a company is founded in its business model [13–15], the latter ne eds to be re-designed to align strategic and operational objectives. Thus offering indus- trial product-service-systems requires a new business model which addresses the customer’s needs by adding value to his processes generating sources of income al- ong the tool’s entire life-cycle. 3. Survey Findings As a base for designing industrial product-service-syste- ms respectively a business model encompassing them, a large scale survey addressing both toolmakers and their customers was conducted. The survey was carried out in two parts, starting with the customers and ending with the toolmakers themselves. In total 278 comp anies in rel- evant economies all over the world participated in the su - rvey. The outcome of the survey was on the one hand an evaluation of tool-related services by both toolmakers Emotional Profile and Customer Experience Emotional Profile and Customer Experience Parts Production Product Design/ Development Tool Productivity and Availability Product Optimization Pilot Series Prototypes Tool System Process Optimization Planning Design and Construction Work Scheduling NC Programming Model Making Tool Manufactu ring Tool Assembly Primary Benefits 1 2 1Integration into customer‘s value chain2Increasing responsibility of the toolmake r Emotional Profile and Customer Experience Emotional Profile and Customer Experience Parts Production Product Design/ Development Tool Productivity and Availability Product Optimization Tool Productivity and Availability Product Optimization Pilot Series Prototypes Pilot Series Prototypes Tool System Process Optimization Tool System Process Optimization Planning Design and Construction Work Scheduling NC Programming Model Making Tool Manufactu ring Tool Assembly Primary Benefits Planning Design and Construction Work Scheduling NC Programming Model Making Tool Manufactu ring Tool Assembly Primary Benefits 1 2 1Integration into customer‘s value chain2Increasing responsibility of the toolmake r 1Integration into customer‘s value chain2Increasing responsibility of the toolmake r Figure 1. Extended product-services within the TIPSS Business Model and parts producers as well as a global footprint of tool makers regarding the provision of these services. The findings referring to the latter are illustrated in the fol- lowing. The global footprint describes the current struc- ture of the tooling indu stry regarding four aspects of ser- vices provision on a global level: 1) Global customers – Are toolmakers taking advan- tage of globalized markets? 2) Local on-site presence – How do toolmakers pro- vide services on a global le vel ? 3) Global partnerships – Do toolmakers cooperate to tackle challenges in teams? 4) Global sourcing – Are toolmakers taking advantage of globalized supply markets? In the following the results of the survey reflecting each of the four dimensions are elaborated. 3.1 Global Customers The first part of the global footprint investigates to which degree toolmakers currently take advantage of globaliza- tion by entering new markets to sell their tools. Figure 2 depicts the structure of the toolmakers’ markets in each region. It can be seen that North American and Western Euro- pean toolmakers still have a very strong focus on their own region. The regions China/South East Asia, and to a 13%13% 13%13% 13% 13% 100% North America South America 0% North Africa 0% Middle East Western Europe Eastern Europe IndiaChinaSouth East Asia 0% Australia North America Percentage of toolmakers that deliver tools within own region Percentage of toolmakers that deliver tools to other regionsPercentage of toolmakers that deliver tools to other regions 44% 36% 11% 22% 51% 14% 24% 12% South America North Africa Middle East 94% Western Europe Eastern Europe IndiaChinaSouth East Asia 6% AustraliaNorth America Western Europe 20% 60% 20% 0% North America 0% South America 0% North Africa Middle East Western Europe 60% Eastern Europe 0% India China 0% South East Asia 0% Australia Eastern Europe 28% 22% 44% 78% 56% 39% 50% 83% North America South America North Africa Middle East Western Europe Eastern Europe India 61% China 33% South East Asia Australia China/ South East Asia Figure 2. Regions to which toolmakers deliver tools  Service Provision in Knowledge-Based Industries – A Global Study on the Tooling Industry Copyright © 2010 SciRes JSSM 140 lesser extent Eastern Europe, have a higher percentage of export to other regions. This shows on the one side, that North America and Western Europe are currently still target markets when it comes to parts production. On the other side it also shows that toolmakers in China/South East Asia and Eastern Europe are using the globalization of markets more consequently for selling their tools. The customer’s point of view is given in Figure 3. The illustration shows th e ratio of global vs. local purchasing of companies within the different regions. Parts produc- ing companies were asked to rank the top four countries from which they purchase tools. It can be seen that com- panies in Western Europe and China/South East Asia frequently purchase tools from toolmakers within their own regio n. Figure 4 illustrates reasons why p arts producing com- panies are hesitant to buy tools outside their own region: Customers were asked to rank the importance of sev- eral disadvantages they perceive when buying tools from toolmakers in other regions of the world on a one- to-seven scale, seven being the most severe disadvantage. The evaluation shows, that a lack of services was ranked just after quality issues and delivery time, clearly implicating the importance for a toolmaker to be able to 17% 34% 45% 65% 83% Western Europe 66% China/ South East Asia 55% North America 35% Eastern Europe 100% Percentage of top 4 r a nked tool supplyi n g countries loc ated within own region Percentage of top 4 r a nked tool supplyi n g countries located in other regions Figure 3. Local vs. global purchasing of tools 4, 3 5, 3 4, 6 4, 8 5,0 4, 6 4,0 3,8 4,8 Price Tool quality Cycle time Warr anty conditions Delivery time Distan ce Lack of services Reputation Language Perceived disadvantage “Lack of service” Disadvant ages perceived by customers (Scale 1 to 7, 7 being the most sever disadvantage) Figure 4. Disadvantages perceived by customers when pur- chasing tools on a global level deliver services on a global level. 3.2 Local on-Site Presence To draw a picture of toolmakers’ on-site presence, parts producer were asked to estimate the percentage of main- tenance work that was conducted by their toolmaker at their production site. Figure 5 shows that a customer’s toolmaker only performs tool related services locally at the customer’s production site in rare cases. This either means that tools are shipped back to the toolmaker for maintenance or that the customer performs maintenance with his on capacities. Figure 6 proves that indeed a large part of the required maintenance work is performed by the customers themselves. Three quarters of the customers state that they conduct more than 50 percent of the maintenance with their own capacities. 3.3 Global Partnerships The third perspective of the global footprint investigates partnerships and other relationships between toolmakers in terms of vertical or horizontal integration into each other’s processes. Toolmakers where asked whether or not they do have any partnerships regarding the provision of services. Figure 7 shows that a large part of the toolmakers, especially in China/South East Asia, is currently not co- operating with other toolmakers for improving service provision (left). The right side of the figure shows the reasons why toolmakers choose not to cooperate. It sticks out that while North American and Western European toolmakers are worried about the protection of their know-how, Chinese/South East Asian toolmakers simply < 80% 4% 7% <= 100%< 40% 4% < 60% 16% 0 60% < 20% 9% 76%76% Percentage of tool related service performed at the customer’s production sit e Figure 5. On-site service provision (customer response) 43% 51-75% 32% 26-50%0-25% 11% 14% 76-100% 75%75% Percentage of maintenance conducted by customer with own capacities Figure 6. Maintenance service performed by customer  Service Provision in Knowledge-Based Industries – A Global Study on the Tooling Industry Copyright © 2010 SciRes JSSM 141 50% 44% 67% 29% The cost is too high Not thought about it yet 16% 3% 57% No appropr. partner found 33% 100% No standard procedure to cooperate 29% 22% 75% 50% Know-how protection 29% Eastern EuropeChina/ South East AsiaWestern EuropeNorth AmericaEastern EuropeEastern EuropeChina/ South East AsiaChina/ South East AsiaWestern EuropeWestern EuropeNorth AmericaNorth America 30% 44% 25% 35% Percentage of toolmakers without partners for service provis ion Figure 7. Percentage of toolmakers without service partners (left), reasons for not having service partners (right) have trouble finding appropriate partners. 3.4 Global Sourcing The last perspective of the global footprint focuses on the ability of the toolmaker to use globalized markets for sourcing. Figure 8 list for each region, which part of the value chain is externalized to the global markets. It can be seen that standard tool parts are the largest part of global sourcing. It seems that while Eastern European and Chinese/South East Asian Toolmakers have a str- onger focus on selling their tools in other regions than their Northern American and Western European coun- terparts, they also go further when it comes to open ing up their value chain to suppliers from other regions. Fur- thermore the graphic shows that while standard tool parts are commonly sourced globally, service are still mostly procured locally. Toolmakers were asked to list advantages and disadvan- tages they perceive when sourcing globally (Figure 9). While North American, Western and Eastern European toolmakers mostly see an advantage in price, Chinese/ South East Asian toolmakers source globally because of quality, reliability, reputation, warranty conditions and, surprisingly, delivery time. 4. Conclusions and Outlooks The analysis of the results showed that only certain as- pects of the challenges regarding global service provision are being adequately addressed by toolmakers in general. When distinguishing between the different regions of the world, it becomes clear that especially emerging markets like China/South East Asia and Eastern Europe are open to take advantage of opportunities lik e global purchasing and exporting of tools. However, local on-site presence as well as partnerships between toolmakers for supplying 17% 14% 25%25% 39% 29% 11% 43% 89% 86% China/ South Ea st Asia Eastern E urope Western Europe North America Complete toolsServices 13% 25% Tailor made toolparts 27% 0% Standard toolpa rts 56% 63% Figure 8. Parts purchased by toolmakers in foreign coun tries by region -0,6 -0,8 -1,2 -0,6 -1,5 -1,2 -0,6 -1,1 -1,1 Customs procedures Deliver y time Distance Warranty Conditions Reliability 1,5 Price Quality Lack of services Communication Reputation -0,5 -0,3 -0,9 -1,1 -0,8 -1,4 -1,1 0,3 -0,6 Delivery time Reputation Lack of services 0,9 Communication Quality Price Distance Reliability Warranty Conditions Customs procedures North AmericaWestern Europe -0,4 -0,9 Deliver y time Customs procedures Reliability Quality Reputation Price Lack of services 1,3 Distance 0,8 0,5 Warranty Conditions 1,5 Communication 2,4 1,1 0,4 1,6 -1,3 -2,0 -2,3 -0,7 -2,3 0,0 -0,3 Warranty Conditions Customs procedures Lack of services 2,7 1,7 Price Reliability Delivery time Reputation 0,7 Communication Quality Distance Eastern EuropeChina/ South East Asia Perceived adv a ntage (scale 0 to 3) Perceived disadvantage (sc a le -3 to 0) Perceived adv a ntage (scale 0 to 3) Perceived disadvantage (sc a le -3 to 0)Perceived disadvantage (sc a le -3 to 0) Figure 9. Advantages and disadvantages of global sourcing perceived by toolmakers  Service Provision in Knowledge-Based Industries – A Global Study on the Tooling Industry Copyright © 2010 SciRes JSSM 142 services are currently still on a very low level in all re- gions of the world. In general the results show, that co- operation among toolmakers is still not common and their ability to deliver tool related services on a global level is not sufficient for the current demand for such services. The results show that in order to be able to offer IPS2, toolmakers have to adapt new business models, which focus on four m ajo r topics: 1) Service provision 2) Cooperation with partners 3) Customer integration 4) Strategies for identifying relevant customer needs Currently each of these four topics is being addressed insufficiently by toolmakers on the whole. Especially smaller toolmakers that do not have the capacities to of- fer adequate services on a global level will have to adjust their business models accordingly. Only through close cooperation with other toolmakers as well as their cus- tomers will they be able to strengthen their position in the vast competition of the globalized markets. The development of an appropriate business model for toolmakers is currently being addressed within the FP7 project TIPSS. Further information on the project as well as the complete evaluation of the TIPSS toolmaking sur- vey can be fo und on the p roject’s website (www.tipss-fp 7.eu). 5. Acknowledgements The research and development project “TIPSS” (Tools for Innovative Product-Product-Service Systems in Glo- bal Tool and Die Networks) is co-funded by the Euro- pean Commission within the Seventh Framework Pro- gramme (FP7). REFERENCES [1] T. Ittner and J. Wüllenweber, “Tough times for toolmak- ers,” The McKinsey Quarterly, Vol. 2, pp. 14–16, 2004. [2] G. Schuh, C. Klotzbach, and F. Gaus, “Business models for technology-supported, production-related services of the tool and die industry,” In S. Takata, and Y. Umeda, (eds.), Advances in Life Cycle Engineering for Sustain- able Manufacturing Businesses, Springer, London, pp. 207–211, 2007. [3] G. Schuh, C. Klotzbach, and F. Gaus, “Service provision as a sub-model of modern business models for tool and die companies,” Proceedings of the 15th CIRP Confer- ence on Life Cycle Engineering, Vol. 2, No. 1, pp. 570– 574, 2008. [4] S. L. Vargo, “Customer integration and value creation,” Journal of Service Research, Vol. 11, No. 2, pp. 211–215, 2008. [5] C. W. Lamb, J. F. Hair, and C. McDaniel, “Marketing, 10th edition,” Cengage Learning, Mason, 2008. [6] M. Lindahl and G. Ölundh, “The meaning of functional sales,” Proceedings of the 8th International Seminar on Life Cycle Engineering, pp. 211–220, 2001. [7] J. F. Castellano, K. Rosenz weig, and H. A. Roehm, “How corporate culture impacts unethical distortion of financial numbers,” Management Accounting Quarterly, Vol. 5, No. 4, pp. 37–41, 2004. [8] R. Lifset, “Moving from product to services,” Journal of Industrial Ecology, Vol. 4, No. 1, pp. 1–2, 2000. [9] V. Salminen and P. Kalliokoski, “Challenges of industrial service business development,” In B. Hefley, and W. Murphy, (eds.), Service Science, Management and Engi- neering, Springer, New York, pp. 41–48, 2007. [10] C. van Halen, C. Vezzoli, and R. Wimmer, “Methodology for product service system innovation,” Assen van Gor- cum, 2005. [11] O. Mont, “Clarifying the concept of product-service sys- tem,” Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 10, No. 3, pp. 237–245, 2002. [12] A. Tan, T. C. McAloone, and C. Gall, “Product/service- system development: An explorative case study in a manufacturing company,” Proceedings of the 16th Inter- national Conference on Engineering Design, 2007. [13] H. I. Ansoff and P. A. Sullivan, “Optimizing profitability in turbulent environments: A formula for strategic suc- cess,” Long Range Planning, Vol. 26, No. 5, pp. 11–24, 1993. [14] H. Mintzberg and J. Lampel, “Reflecting on the strategy process,” Sloan Management Review, Vol. 40, No. 3, pp. 21–30, 1999. [15] G. Schuh, C. Klotzbach, and F. Gaus, “Service provision as a sub-model of modern business models,” Production Engineering Research and Development, Vol. 1, No. 2, pp. 79–84, 2008. |