Applied Mathematics

Vol.07 No.17(2016), Article ID:72426,16 pages

10.4236/am.2016.717179

Nonparametric Regression Estimation with Mixed Measurement Errors

Zanhua Yin, Fang Liu, Yuanfu Xie

College of Mathematics and Computer Science, Gannan Normal University, Ganzhou, China

Copyright © 2016 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received: May 20, 2016; Accepted: November 27, 2016; Published: November 30, 2016

ABSTRACT

We consider the estimation of nonparametric regression models with predictors being measured with a mixture of Berkson and classical errors. In practice, the Berkson error arises when the variable X of interest is unobservable and only a proxy of X can be measured while the inaccuracy related to the observation of the proxy causes an error of classical type. In this paper, we propose two nonparametric estimators of the regression function in the presence of either or both types of errors. We prove the asymptotic normality of our estimators and derive their rates of convergence. The finite-sample properties of the estimators are investigated through simulation studies.

Keywords:

Berkson Error, Classical Error, Deconvolution, Kernel Method, Mixed Measurement Errors

1. Introduction

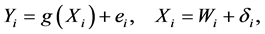

Let  denote a sequence of independent and identically distributed random vectors. In traditional non-parametric regression model analysis, one is in- terested in the following model

denote a sequence of independent and identically distributed random vectors. In traditional non-parametric regression model analysis, one is in- terested in the following model

(1)

(1)

where  is assumed to be a smooth, continuous but unknown function; the random errors

is assumed to be a smooth, continuous but unknown function; the random errors  are assumed to be normally and independently distributed with mean 0 and constant variance

are assumed to be normally and independently distributed with mean 0 and constant variance ; and

; and . Here, the predictor X is usually assumed to be directly observable without errors. Both the direct observation and error-free assumptions are however seldom true in most epidemiologic studies. For the violation of the error-free assumption, [1] considered an environmental study which studied the relation of mean exposure to lead up to age 10 (denoted as X) with intelligence quotient (IQ) among 10-year-old children (denoted as Y) living in the neighborhood of a lead smelter. Each child had one measurement made of blood lead (denoted as W), at a random time during their life. The blood lead measurement (i.e., W) became an approximate measure of mean blood lead over life (X). However, if we were able to make many replicate measurements (at different random time points), the mean would be a good indicator of lifetime exposure. In other words, the measure- ments of X are subject to errors and W is a perturbation of X. In the measurement error literature, this is known as the classical error model and Model (1) becomes

. Here, the predictor X is usually assumed to be directly observable without errors. Both the direct observation and error-free assumptions are however seldom true in most epidemiologic studies. For the violation of the error-free assumption, [1] considered an environmental study which studied the relation of mean exposure to lead up to age 10 (denoted as X) with intelligence quotient (IQ) among 10-year-old children (denoted as Y) living in the neighborhood of a lead smelter. Each child had one measurement made of blood lead (denoted as W), at a random time during their life. The blood lead measurement (i.e., W) became an approximate measure of mean blood lead over life (X). However, if we were able to make many replicate measurements (at different random time points), the mean would be a good indicator of lifetime exposure. In other words, the measure- ments of X are subject to errors and W is a perturbation of X. In the measurement error literature, this is known as the classical error model and Model (1) becomes

(2)

(2)

where , are mutually independent and

, are mutually independent and  represents the classical measurement error variable. Various methods and approaches for analyzing Model (2) such as deconvolution kernel approaches (e.g., [2] [3] [4] ), design-adaptive local poly- nomial estimation method (e.g., [5] ), methods based on simulation and extrapolation (SIMEX) arguments (e.g., [6] [7] [8] [9] ), and Bayesian approach (e.g., [10] ) have been extensively studied in the literature.

represents the classical measurement error variable. Various methods and approaches for analyzing Model (2) such as deconvolution kernel approaches (e.g., [2] [3] [4] ), design-adaptive local poly- nomial estimation method (e.g., [5] ), methods based on simulation and extrapolation (SIMEX) arguments (e.g., [6] [7] [8] [9] ), and Bayesian approach (e.g., [10] ) have been extensively studied in the literature.

In many studies, it is however too costly or impossible to measure the predictor X exactly or directly. Instead, a proxy W of X is measured. For the violation of the direct observation assumption, [1] modified the aforementioned environmental study in which the children’s place of residence at age 10 (assumed known exactly) were classified into three groups by proximity to the smelter―close, medium, far. Random blood lead samples, collected as describe in the aforementioned design, were averaged for each group (denoted as W), and this group mean used as a proxy for lifetime exposure for each child in the group. Here, the same approximate exposure (proxy) is used for all subjects in the same group, and true exposures, although unknown, may be assumed to vary randomly about the proxy. This is the well-known Berkson error model. In other words, the predictor X are not directly observable and measurements on its surrogates W are available instead. The true predictor X is then a perturbation of W. The model of interest now becomes

(3)

(3)

where , are mutually independent. Model (3) was first con- sidered by [11] and the estimation of the linear Berkson measurement error models was discussed in [12] . Methods based on least squares estimation ( [13] ), minimum distance estimation ( [14] [15] ), regression calibration ( [16] ) and trigonometric functions ( [17] ) have been studied.

, are mutually independent. Model (3) was first con- sidered by [11] and the estimation of the linear Berkson measurement error models was discussed in [12] . Methods based on least squares estimation ( [13] ), minimum distance estimation ( [14] [15] ), regression calibration ( [16] ) and trigonometric functions ( [17] ) have been studied.

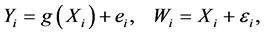

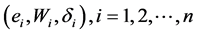

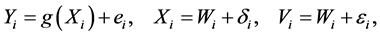

The stochastic structure of Model (3) is fundamentally different from Model (2). Here, the measurement error of Model (2) is independent of X, but dependent on W. This distinctive feature leads to completely different procedures in estimation and inference for the models. In particular, nonparametric estimators that are consistent in Model (2) are no longer valid in Model (3), and vice versa. In most of the existing literature, the measurement error is supposed to be only one of the two types. In the Berkson model (3), it is usually assumed that the observable variable W is measured with perfect accuracy. However, this may not be true in some situations. In such cases, W is observed through , where

, where  is a classical measurement error. [18] presented a good discussion of the origins of mixed Berkson and classical errors in the context of radiation dosimetry. Under this mixture of measurement errors, we observe a random sample of independent pairs

is a classical measurement error. [18] presented a good discussion of the origins of mixed Berkson and classical errors in the context of radiation dosimetry. Under this mixture of measurement errors, we observe a random sample of independent pairs , for

, for , generated by

, generated by

(4)

(4)

where ,

,  ,

,

This paper is organised as follows. In Section 2, we propose estimators for the regression function curve

2. Proposed Estimators

Let

Hence, if

Since

Noticing that, if

under the condition that

where

As a result, we propose the following estimator for

Example 1 Let the error densities

ratio

where

Using a kernel function

and an estimator for

where

Proceeding as above, we get an alternative estimator of

where

Therefore, when (6) is no longer valid, we propose the following estimator for

Remark 1 To ensure that the proposed estimator (9) is well-behaved, we need to make the following assumption.

Condition A:

1.

2.

Example 2 We use the same model as in Example 1 with

Remark 2

1. The above two nonparametric estimators of

2. When the variance of

where

3. When the variance of

3. Theoretical Properties

In this section, we study asymptotic properties of the estimators proposed in Section 2. In particular, the properties of the estimator

3.1. Asymptotic Results for

In this section, we investigate the large-sample properties of the estimator

Condition B:

1.

2.

3.

4. The conditional moment

Let

Theorem 1 ((MSCE)) Suppose that Conditions A and B hold. Then, for each x such that

where

Explicit rates of convergence of the estimator

where

The second term on the right-hand side of Equation (11) describes the variance of

1. An exponential ratio of order

with

2. A polynomial ratio of order

with

3.1.1. Asymptotic Mean Squared Error (AMSE)

In this section, we study the asymptotic behaviour of the MSE where

Theorem 2 Suppose that Conditions A and B hold and that the first half inequality of (12) is satisfied. Assume that

with

When

Theorem 3 Suppose Conditions A and B hold, and that

under the polynomial ratio (13), for each x such that

with

We obtain that, when

3.1.2. Asymptotic Normality

The theorem below establishes asymptotic normality in the exponential ratio case.

Theorem 4 Under the conditions of Theorem (2), and for bandwidth

where

The next theorem establishes asymptotic normality in the polynomial ratio case.

Theorem 5 Suppose that Conditions A and B hold and that the inequality of (13) is satisfied. Assume that

where

The proofs of all theorems are postponed to the Appendix.

3.2. Unknown Measurement Error Distribution

When the error densities are unknown, they can be readily estimated from additional observations (e.g., a sample from the error densities, replicated data or external data) and these estimates can be substituted into (6) and (9) to produce the estimate of

4. Simulation Studies

We study numerical properties of the estimators proposed in Section 2. Note that we have defined two estimators, at (6) and (9). The first exists when

We apply the various estimators introduced above to some simulated examples (see, [23] ):

1.

2.

3.

where

In our simulations we consider sample sizes

Figure 1 and Table 1 illustrate the way in which the estimator improves as sample size increases. We compare, for various sample sizes, the results obtained for estimating curve (a) when

For any nonparametric method for regression problem, the quality of the estimator also depends on the discrepancy of the observed sample. That is, for any given family of densities

Figure 1. Estimation of curve (a) for samples of size n = 50 (left panel), n = 100 (middle panel) or n = 250 (right panel), when

Table 1. MISE

Finally, we compare

5. Discussion

In this paper, we propose a new method for estimating non-parametric regression models with the predictors being measured with a mixture of Berkson and classical errors. The method is based on the relative smoothness of

Figure 2. Estimation of function (c) for samples of size

Figure 3. Boxplots of the quantities of log(ISEO/ISEI) (row 1) and log(ISEO/ISEC) (row 2) for estimating regression curve (a) when

Table 2. MISE

Table 3. MISE for estimation of curve (c) when

smooth enough (relative to

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Natural Science Foundation of Jiangxi Province of China under grant number 20142BAB211018.

Cite this paper

Yin, Z.H., Liu, F. and Xie, Y.F. (2016) Nonparametric Regression Estimation with Mixed Measurement Errors. Applied Mathematics, 7, 2269-2284. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/am.2016.717179

References

- 1. Armstrong, B.G. (1998) Effect of Measurement Error on Epidemiological Studies of Environmental and Occupational Exposures. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 55, 651-656.

https://doi.org/10.1136/oem.55.10.651 - 2. Fan, J. and Truong, Y.K. (1993) Nonparametric Regression with Errors in Variables. Annals of Statistics, 21, 1900-1925.

https://doi.org/10.1214/aos/1176349402 - 3. Delaigle, A. and Meister, A. (2007) Nonparametric Regression Estimation in the Heteroscedastic Errors-in-Variables Problem. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 102, 1416-1426.

https://doi.org/10.1198/016214507000000987 - 4. Delaigle A., Hall, P. and Meister A. (2008) On Deconvolution with Repeated Measurements. Annals of Statistics, 36, 665-685.

https://doi.org/10.1214/009053607000000884 - 5. Delaigle, A., Fan, J. and Carroll, R.J. (2009) A Design-Adaptive Local Polynomial Estimator for the Errors-in-Variables Problem. Journal of the American Statistical Association 104, 348-359.

https://doi.org/10.1198/jasa.2009.0114 - 6. Cook, J.R. and Stefanski, L.A. (1994) Simulation-Extrapolation Estimation in Parametric Measurement Error Models. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 89, 1314-1328.

https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1994.10476871 - 7. Stefanski, L.A. and Cook, J.R. (1995) Simulation-Extrapolation: The Measurement Error Jackknife. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 90, 1247-1256.

https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1995.10476629 - 8. Carroll, R.J., Maca, J.D. and Ruppert, D. (1999) Nonparametric Regression in the Presence of Measurement Error. Biometrika, 86, 541-554.

https://doi.org/10.1093/biomet/86.3.541 - 9. Staudenmayer, J. and Ruppert, D. (2004) Local Polynomial Regression and Simulation-Extrapolation. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B, 66, 17-30.

https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1369-7412.2003.05282.x - 10. Berry, S.M., Carroll, R.J. and Ruppert, D. (2002) Bayesian Smoothing and Regression Splines for Measurement Error Problems. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 97, 160-169.

https://doi.org/10.1198/016214502753479301 - 11. Berkson, J. (1950) Are There Two Regression Problems? Journal of the American Statistical Association, 45, 164-180.

https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1950.10483349 - 12. Fuller, W. (1987) Measurement Error Models. Wiley, New York.

https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470316665 - 13. Huwang, L. and Huang, H.Y.S. (2000) On Errors-in-Variables in Polynomial Regression— Berkson Case. Statistica Sinica, 10, 923-936.

- 14. Wang, L. (2003) Estimation of Nonlinear Berkson-Type Measurement Error Models. Statistica Sinica, 13, 1201-1210.

- 15. Wang, L. (2004) Estimation of Nonlinear Models with Berkson Measurement Errors. Annals of Statistics, 32, 2559-2579.

https://doi.org/10.1214/009053604000000670 - 16. Carroll, R.J., Delaigle, A. and Hall, P. (2009) Nonparametric Prediction in Measurement Error Models. ournal of the American Statistical Association, 104, 993-1003.

https://doi.org/10.1198/jasa.2009.tm07543 - 17. Delaigle, A., Hall, P. and Qiu, P. (2006) Nonparametric Methods for Solving the Berkson Errors-in-Variables Problem. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B, 68, 201-220.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9868.2006.00540.x - 18. Schafer, D.W. and Gilbert, E.S. (2006) Some Statistical Implications of Dose Uncertainty in Radiation Dose-Response Analyses. Radiation Research, 166, 303-312.

https://doi.org/10.1667/RR3358.1 - 19. Reeves, G.K., Cox, D.R., Darby, S.C. and Whitley, E. (1998) Some Aspects of Measurement Error in Explanatory Variables for Continuous and Binary Regression Models. Statistics in Medicine, 17, 2157-2177.

https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19981015)17:19<2157::AID-SIM916>3.0.CO;2-F - 20. Schafer, M., Mullhaupt, B. and Clavien, P.A. (2002) Evidence-Based Pancreatic Head Resection for Pancreatic Cancer and Chronic Pancreatitis. Annals of Surgery, 236, 137-148.

https://doi.org/10.1097/00000658-200208000-00001 - 21. Mallick, B., Hoffman, F.O. and Carroll, R.J. (2002) Semiparametric Regression Modeling with Mixtures of Berkson and Classical Error, with Application to Fallout from the Nevada Test Site. Biometrics, 58, 13-20.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0006-341X.2002.00013.x - 22. Delaigle, A. (2007) Nonparametric Density Estimation from Data with a Mixture of Berkson and Classical Errors. Canadian Journal of Statistics, 35, 89-104.

https://doi.org/10.1002/cjs.5550350109 - 23. Carroll, R.J., Delaigle, A. and Hall, P. (2007) Nonparametric Regression Estimation from Data Contaminated by a Mixture of Berkson and Classical Errors. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B, 69, 859-878.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9868.2007.00614.x - 24. Hu, Y. and Schennach, S.M. (2008) Identification and Estimation of Nonclassical Nonlinear Errors-in-Variables Models with Continuous Distributions. Econometrica, 76, 195-216.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0012-9682.2008.00823.x - 25. Fan, J. (1991) Asymptotic Normality for Deconvolution Kernel Density Estimators. Sankhya A, 53, 97-110.

Appendix

Proof of Theorem 1

Let

and

where

Proofs of the Results of Section 3.1.1.

Lemma 1 Suppose that

where, here, and below, C denotes a generic positive and finite constant.

Proof. It follows from (A2) of Condition A that

The conclusion follows from

The proof for the other result is similar and requires Parseval's Theorem.

From (14) and Lemma 1, we have

The proof of Theorem 2 follows from the expressions of

The proof of Theorem 3 is the same as the proof of Theorem 2, but in this case we need the following lemma.

Lemma 2 Suppose that

with

The proof of Lemma 2 is similar to the proof of Lemma 1 and is omitted.

Proofs of the Results of Section 3.1.2.

A standard decomposition gives

is that the Lyapounov's condition holds, i.e., for some

Letting

Under the conditions given in the theorem 4, we can prove that

Under the conditions given in the theorem 5, we can prove that

The rest is standard and is omitted.