Psychology

Vol.5 No.10(2014), Article

ID:48883,11

pages

DOI:10.4236/psych.2014.510141

The Relationship between Work-Stress, Psychological Stress and Staff Health and Work Outcomes in Office Workers

Einar B. Thorsteinsson1*, Rhonda F. Brown2*, Carlie Richards1*

1University of New England, Armidale, Australia

2The Australian National University, Canberra, Australia

Email: ethorste@une.edu.au

Copyright © 2014 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 16 June 2014; revised 13 July 2014; accepted 4 August 2014

ABSTRACT

This study examined associations between work-stress, perceived organizational support, supervisor support, staff health (i.e., psychological stress, anxiety, depression, fatigue), and work outcomes (i.e., turnover intentions, organizational commitment, job satisfaction). A heterogeneous sample of 201 office staff recruited via email and snowball sampling completed a short anonymous online survey asking about their recent experiences of the above factors. High work-stress was associated with worse staff health (i.e., anxiety, depression, fatigue) and work outcomes (e.g., greater turnover intentions), and these associations were mediated by high perceived stress. Less workplace support (i.e., supervisor support, perceived organizational support) was associated with adverse work outcomes (i.e., high turnover intentions, less organizational commitment, less job satisfaction), and high depression levels. Neither perceived organizational support nor supervisor support was shown to moderate between high work-stress to the staff health and work outcome associations. Work-stress likely contributed to feelings of high perceived stress in some workers, which then contributed to poor health and higher turnover intentions. However, workplace support did not appear to buffer against the potential to experience ill health or adverse work outcomes (e.g., less job satisfaction). This study examines gaps in the work-stress literature, particularly in relation to adverse work outcomes and the possible impact of organizational support in reducing these and staff health problems.

Keywords:Work-Stress, Psychological Stress, Anxiety, Depression, Fatigue, Organizational Support, Supervisor Support

1. Introduction

Work-stress is defined as any harmful response occurring in staff when the requirement to get the job done does not match the actual or perceived ability to do the job (Folkman, Lazarus, Pimley, & Novacek, 1987). In 2009, Australian workers’ compensation claims that result from work-stress resulted in more than 10 working weeks lost person per year, which is more than double the median time lost for all other worker’s compensation claims (National Occupational Health and Safety Commission, 2010).

Work-stress is strongly correlated with negative staff mental health outcomes. For example, greater psychological stress was reported in nurses when work-stress was prolonged or there was low decisional latitude (Bourbonnais, Comeau, & Vézina, 1999), with similar results reported in a Canadian national health survey (Vermeulen & Mustard, 2000). When work-stress (e.g., high demands and low control) is high and/or combined with high job insecurity, staff are also at an increased risk of anxiety and depression (Strazdins, D’Souza, Lim, Broom, & Rodgers, 2004), and this is paralleled by higher psychological strain, as indexed by an increase in systolic blood pressure (Capizzi, Allen, Murphy, & Pescatello, 2010).

In addition, work-stress is linked to the experience of fatigue (Åkerstedt, Knutsson, Westerholm, Theorell, Alfredsson, & Kecklund, 2002) with fatigue prevalence rates reportedly around 20% in working adults (Kant, Bültmann, Schröer, Beurskens, van Amelsvoort, & Swaen, 2003; Pawlikowska, Chalder, Hirsch, Wallace, Wright, & Wessely, 1994). This work-related fatigue is thought to be the result of emotional and mental exhaustion occurring in the context of work-stress and burnout, and it is frequently co-morbid with anxiety, depression, and substance use (e.g., Appels, 2000; Kant et al., 2003).

Recent research suggests that when staff feel supported in the workplace they become better equipped to deal with everyday work-stressors (Cropanzano, Howes, Grandey, & Toth, 1997). Social Exchange Theory has been used to contextualize such work social interactions (e.g., management support) from a cost-benefit perspective. Eisenberger, Huntington, Hutchison, and Sowa (1986) proposed that workers form assumptions about how valuable they are to an organization, and this combined with their assessment of how the organization cares about them is referred to as their perceived organizational support (POS). When POS is high, part-time staff report experiencing less psychological stress, suggesting they perceive fewer threats in the workplace. The work environment is also perceived as more stable and predictable, leaving staff to focus on the task at hand (Cropanzano et al., 1997).

However, few studies have examined POS (and related constructs, e.g., supervisor support) in relation to work-stress and staff health (e.g., anxiety, depression) associations; in particular, whether POS can moderate (i.e., reduce) the strength of association between high work-stress to the above outcomes, thus potentially buffering against the putative adverse impact of work-stress on staff health. As detailed below, findings in the small relevant literature are patchy and often contradictory; for example, there are no studies examining POS in relation to staff mental health outcomes although several analogous constructs have been examined. In addition, only one study has examined POS in relation to work-stress and fatigue (Cropanzano et al., 1997), but they confounded the measurement of these variables by combining them into a single measure that was related to POS and organizational politics.

Using analogous support constructs, low work social support has previously been linked to greater staff psychological stress and this association is strongest in higher strain jobs. The results suggest that the work support may buffer against the putative adverse impact of high work-stress on mental health (Vermeulen & Mustard, 2000). However, in another study, work support did not moderate between high work-stress to psychological stress in nurses (Bourbonnais et al., 1999), although in other studies low workplace social support was linked to worse depression symptoms (Kopp, Stauder, Purebl, Janszky, & Skrabski, 2008) and fatigue (Wada et al., 2008). In addition, in the general health literature, social support is a well-known moderator of high-stress to health outcome associations including depression and fatigue (Thorsteinsson & Brown, 2009; Zhang, Shi, Wang et al., 2005).

Similarly, supervisor support or the degree to which supervisors value the contribution of staff and care about their well-being (Kottke & Sharafinski, 1988) is inconsistently linked to work-stress in the literature. In two studies, high supervisor support was related to low work-tension (Chen & Chiu, 2008), less work overload, jobstress, and turnover intentions (Brotheridge & Lee, 2005), whereas in another study, it was unrelated to workstress (Hammer, Saksvik, Nytrø, Torvatn, & Bayazit, 2004). Thus, in this study, we examined whether supervisor support was correlated with and moderated between high work-stress to adverse health outcome associations. We also assessed staff perceptions of work-stress and fatigue severity separately, and examined them individually in relation to POS. In addition, since there is a lack of clarity as to whether workplace support can moderate between high work-stress to low psychological stress, we examined the premise in this study.

For example, the relationship between work-stress to organizational commitment has yet to be examined, although Schmidt (2007) noted that when work commitment is high, work-stress is unrelated to burnout; thus, we examined whether the variables were related to each other in this study. According to Social Exchange Theory, when POS is high, staff feels obligated to reciprocate the support, which is referred to as organizational commitment, or the strength of staff identification with and involvement in an organization (Porter, Steers, Mowday, & Boulian, 1974). In confirmation of this theory, robust associations have been reported between POS (and supervisor support) and organizational commitment, as evidenced by more regular work attendance in hospital workers (Settoon, Bennett, & Liden, 1996).

Furthermore, work-stress, turnover intentions, and job satisfaction are known to be interrelated, although no indirect mediational pathways have been tested. For example, work-stress (e.g., work overload) was shown to be related to higher turnover intentions (i.e., workers’ intentions to depart or quit an organization), with the intentions shown to reliably precede actual job turnover (Jamal, 2007), with similar results reported in engineers (Riolli & Savicki, 2006) and truck drivers (de Croon, Sluiter, Blonk, Broersen, & Frings Dresen, 2004). However, the need for recovery after work was shown to fully mediate between high job demands to greater job turnover in the latter study, although no studies have examined whether psychological stress can mediate between high work-stress to adverse work outcomes, and so we examined the premise in this study.

Finally, work-stress is known to be related to less job satisfaction, but again indirect meditational pathways have not been tested. For example, Cavanaugh et al. (2000) found that hindrance-related stress (i.e., stress linked to negative feelings and distress) predicted more job dissatisfaction, whereas challenge-related stress (i.e., stress linked to positive feelings and success) predicted less job dissatisfaction, with similar associations reported between work-stress, personal stress, and job dissatisfaction in care workers (Ejaz, Noelker, Menne, & Bagaka’s, 2008). POS is also related to higher job satisfaction (Erdogan & Enders, 2007), but the variable (and supervisor support) have yet to be examined as potential moderators of work-stress to job satisfaction associations, and so we tested the assertion in this study.

Thus, in summary, we examined associations between work-stress, POS, supervisor support, staff health (i.e., perceived stress, anxiety, depression, fatigue), and work outcomes (i.e., turnover intentions, organizational commitment, job satisfaction), in a heterogeneous sample of office workers. In accordance with the limited available literature, including that examining analogous work-support constructs, we expected that:

1a) high work-stress will be related to: greater psychological stress, anxiety, depression, fatigue, and turnover intentions, and less job satisfaction; associations between work-stress to organizational commitment were examined making no a priori assertions;

1b) low POS will be related to more psychological stress, depression, and turnover intentions, and less job satisfaction; and low supervisor support will be related to high turnover intentions;

2) high psychological stress will mediate between high work-stress to high anxiety, depression, fatigue, turnover intentions, and less job satisfaction; and3) POS and supervisor support will moderate between high work-stress to less psychological stress, depression, fatigue, turnover intentions, and job satisfaction. All previously untested associations between POS, supervisor support, staff health, and work outcomes will be examined making no a priori assertions.

2. Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement and Consent

This study was conducted with full human research ethics committee approval by the University of New England, Australia, Human Research Ethics Committee; approval number HE08/023. All interactions with participants were online. Potential participants were provided with information about the study and informed in writing of their right to withdraw at any time from the study. All participants indicated their consent after reading an information sheet; all participants ticked a box online to indicate their understanding of the information given and to give their consent to participate in the present study. Participants could not proceed past the information and consent screens to the questionnaires without giving their consent. This consent procedure fulfilled all requirements of the University of New England, Australia, Human Research Ethics Committee.

2.2. Participants

Participants were recruited via office-based contacts of the researcher (CB) in 51 organizations who were sent an explanatory email about the study. Additional participants were recruited via email snowballing. The introductory email described the study and provided a URL link to an online work-stress survey. Workers were eligible to participate if they were over 18 years of age and worked in an office environment. Two-hundred-thirtytwo people agreed to participate in the study, with 31 eliminated due to excessive missing data, leaving 201. An a priori power analysis determined that 184 participants were required, assuming a small effect size of f2 = .07 (due to the lack of studies examining the associations) power of .90, an alpha of .05, and two predictors.

Participants ranged in age from 18 to 67 years (M = 35.29 years, SD = 10.29) with one person not reporting their age. Most staff worked full-time (73%, 147), but a significant proportion (27%, 54) worked part-time or casual. One-half of respondents were married/de facto (54%, 108), one-third were never married (35%, 71), and the remainder were widowed, divorced, separated, or unspecified (11%, 22). Most held a postgraduate degree (23%, 47), university/college degree (35%, 70) or trade certificate/diploma (20%, 41) as their highest level of qualification, with the remainder completing their Year 12/Higher School Certificate or equivalent (19%, 38), or Year 10 or below (3%, 5).

2.3. Procedure

Participants received an email describing the study and directing them to an anonymous online work-stress survey. If they wished to participate, they indicated their informed consent by ticking a box on the computer screen. They then completed a short survey asking about their recent experiences of work-stress, psychological stress, anxiety, depression, fatigue, POS, supervisor support, turnover intentions, organizational commitment and job satisfaction.

2.4. Instruments

Work-stress over the past month was assessed using the 4-item version of Cohen, Kamarck, and Mermelstein’s (1983) Perceived Stress Scale. This scale assesses the degree to which particular situations (i.e., workplace) are appraised as stressful. Participants rated their level of agreement with the statements, from 1 (never) to 5 (very often), with high scores indicating greater work-stress. Internal consistency for the scale is adequate with a reported coefficient alpha reliability of .72 (Cohen et al., 1983). In this study, the internal consistency was high with a Cronbach’s alpha of .87.

Organizational support was assessed using the Survey of Perceived Organizational Support (POS Short Form; Eisenberger et al., 1986), a 16-item scale assessing how supported staff feels by their organization by examining the extent to which they feel their employer would go to ensure their well-being or retain their services. Staff rated their level of agreement with statements about the extent to which their organization valued them, from 1 (completely disagree) to 7 (completely agree), with high scores indicating greater POS. The scale has high internal consistency with a Cronbach’s alpha of .97 and good construct validity (Shore & Tetrick, 1991). In this study, internal consistency was high with a Cronbach’s alpha of .94.

Supervisor support was assessed using the 5-item version of the House and Dessler’s Measures of Leadership Support and Consideration scale (as cited and used by Chiu, Chien, Lin, & Hsiao, 2005). The scale assesses the degree to which staff feels their direct supervisor is providing guidance, support and consideration of their input, with high scores indicating greater perceived supervisor support. The scale has adequate internal consistency with a Cronbach’s alpha of .71 and good convergent and discriminant validity (Chiu et al., 2005). In this study, internal consistency for the scale was high with a Cronbach’s alpha of .90.

Stress, anxiety and depression over the past week were assessed using the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS-21; Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995). The stress scale assesses feelings of irritability and tension, the anxiety scale assesses fear and anxious pathology (e.g., panic attack), and the depression scale assesses symptoms of dysphoric mood. The subscales have high internal consistencies with Cronbach’s alphas for depression of .94, .87 for anxiety and .91 for stress, and good concurrent validity (Antony, Bieling, Cox, Enns, & Swinson, 1998). In this study, internal consistencies were high with Cronbach’s alphas of .88 for depression, .80 for anxiety and .87 for stress.

Fatigue was assessed using the Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS; Krupp, LaRocca, Muir-Nash, & Steinberg, 1989), a 9-item scale assessing functional impairments resulting from fatigue over the past week. Staff rated their level of agreement with statements from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), with high scores indicating worse fatigue. The scale has high internal consistency in healthy controls with Cronbach’s alphas ranging from .81 to .89 (Krupp et al., 1989). In this study, internal consistency was high with a Cronbach’s alpha of .87.

Turnover intentions were assessed using Bluedorn’s (1982) 4-item Turnover Intentions Scale, reported to bear the closest relationship of all such measures to actual job turnover (Chiu et al., 2005). Staff rated their level of agreement with statements from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree), with high scores indicating a stronger intention to leave an organization. The scale has high internal consistency with a Cronbach’s alpha of .81 (Bluedorn, 1982). In this study, internal consistency was high with a Cronbach’s alpha of .88.

Organizational commitment was assessed using the 5-item version of Mowday, Steers, and Porter’s (1979) Organizational Commitment Questionnaire. Staff were asked to rate their level of agreement with statements, from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree), with high scores indicating greater commitment to the organization. The scale has adequate internal consistency with Cronbach’s alphas ranging from .75 to .79, and good convergent and discriminant validity (Chiu et al., 2005). In this study, internal consistency for the scale was adequate with a Cronbach’s alpha of .72.

Job satisfaction was assessed using the 5-item version of Konrad et al.’s (1999) Global Job Satisfaction Scale. Workers rated their agreement with statements, from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree), with high scores indicating greater job satisfaction. The scale has high internal consistency with Cronbach’s alphas ranging from .82 to .88, and good content, convergent and discriminant validity (Williams et al., 1999). In this study, the internal consistency was high with a Cronbach’s alpha of .84.

2.5. Statistical Analyses and Interpretation

SPSS v19 was used for routine statistical analyses. Multiple linear regressions were used to determine potential moderators (i.e., workplace support variables) of the work-stress to mental health and work outcome relationships. Moderation was tested using centered moderators and independent variables to calculate an interaction term (i.e., independent variable by moderator). This interaction term was entered with the independent variable and moderator in the regression equation, with a significant interaction term indicating significant moderation.

Mediation was performed using the bootstrap method of Preacher and Hayes (2004). This method compares coefficients for the total effect, path c (effects of independent variable on the dependent variable without any mediators) with the coefficient for the direct effect c’ (effects of independent variable on the dependent variable with any mediators included). There was significant mediation if the c-c’ difference was larger than zero based on a 95% confidence interval. The confidence interval was calculated using a bootstrap re-sampling method with 2000 samples. If c’ becomes non-significant after controlling for the mediator, full mediation is present. If c’ is significantly reduced from c, but still statistically significant, partial mediation is present.

The suggested model based on the present study was assessed using 1) the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) which ranges from 0 to 1 with values above .90 suggesting a good fit; 2) the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) with values below or close to .06 being good; 3) the Tucker-Lewis coefficient (TLI) with values close to 1.0 indicating good fit; and 4) a Chi-square based index (Chi-square/df) with values close to 3 or below showing a good fit.

3. Results

Means and standard deviations of all key variables are provided in Table1 Based on suggested FSS cut-offs (i.e., mean score > 4.7; Krupp et al., 1989), 24% of the sample had clinically relevant (i.e., severe) fatigue. Regarding Hypothesis 1, the correlation matrix of key variables shows that psychological stress was highly correlated with work-stress, anxiety, and depression and moderately correlated with fatigue and all the work outcomes; see Table1 The emotional state variables (i.e., work-stress, psychological stress, anxiety, depression) were highly intercorrelated, as were the work outcome variables.

Regarding Hypothesis 1, standard multiple regressions were conducted testing work-stress, POS, and supervisor support as independent variables, and psychological stress, anxiety, depression, fatigue, and the work outcomes as dependent variables. Table 2 shows that work-stress predicted: psychological stress, R2 adjusted = .42, F(3, 197) = 50.10, p < .001; anxiety, R2 adjusted = .29, F(3, 197) = 27.64, p < .001; and fatigue, R2 adjusted = .08, F(3, 197) = 6.96, p < .001; work-stress and POS both predicted depression, R2 adjusted = .26, F(3, 197) = 24.49, p < .001; and turnover intentions, R2 adjusted = .25, F(3, 197) = 22.78, p < .001; and work-stress, POS

Table 1 . Correlation matrix for the key measures (N = 201).

Note: Correlation coefficients relevant to Hypothesis 1 are bolded. *p < .05, **p < .001.

and supervisor support predicted job satisfaction , R2 adjusted = .49, F(3, 197) = 65.77, p < .001; but only POS and supervisor support predicted organizational commitment, R2 adjusted = .44, F(3, 197) = 52.55, p < .001.

As for Hypothesis 2, psychological stress was found to fully mediate between high work-stress to worse anxiety, depression, and fatigue, and it partly mediated between high work-stress to greater turnover intentions, see Table3 When it came to Hypothesis 3, neither POS nor supervisor support were shown to moderate between high work-stress to psychological stress, anxiety, depression, fatigue, turnover intentions, organizational commitment, or job satisfaction; see Table4

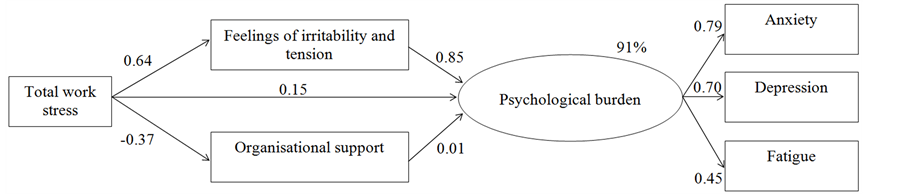

Finally, a model that included all significant associations was tested using structural equation modeling. The fit indices indicated a good fit and a strong meditational effect was shown for psychological stress (i.e., feelings of irritability and tension in the model). Overall 91% of the variance in psychological burden was explained by the model, CFI = .958, TLI = .910, RMSEA = .119 [90% CI .073, .168], Chi-square/df = 3.81; see Figure 1.

4. Discussion

Work-stress was shown to be strongly related to all staff health outcomes (i.e., psychological stress, anxiety, depression, fatigue) and most of the work outcomes, except organizational commitment. These findings are consistent with Hypothesis 1 and prior literature reports of significant associations between high work-stress to worse psychological stress, anxiety, depression (Hammer et al., 2004; Strazdins et al., 2004), fatigue (e.g., Åkerstedt et al., 2002), and turnover intentions (de Croon et al., 2004; Riolli & Savicki, 2006), and less job satisfaction (Cavanaugh et al., 2000).

However, workplace support (i.e., POS, supervisor support) was mostly unrelated to staff health outcomes, except that low POS was significantly related to high depression levels, which is consistent with prior literature reports of low work social support being related to worse depression levels (Kopp et al., 2008). However, low POS was unrelated to high psychological stress levels, inconsistent with prior studies indicating such a lack of support was related to high psychological stress (Vermeulen & Mustard, 2000).

As expected, POS and supervisor support were related to most of the work outcomes, as detailed below. Low POS and supervisor support were related to less job satisfaction and organizational commitment, whereas low POS was related to greater turnover intentions, somewhat consistently with Hypothesis 1, and prior reported associations between POS, job satisfaction (Erdogan & Enders, 2007), and organizational commitment (Settoon et

Table 2. Predictors of psychological stress, anxiety, depression, fatigue, and work outcomes (N = 201).

Note: The semi-partial (sr) correlation given is the Part correlation in SPSS. The r given is for the zero-order correlation. No multivariate outliers were detected; criteria χ2(3, .001) = 16.27. * p < .05 (one-tailed), ** p < .01 (one-tailed).

al., 1996). However, the results are inconsistent with prior reported associations between low supervisor support and high turnover intentions (Brotheridge & Lee, 2005), although they occur in the context of inconsistent workstress to supervisor support associations (Brotheridge & Lee, 2005; Chen & Chiu, 2008; Hammer et al., 2004).

Taken together, the results suggest that adverse staff health outcomes (i.e., stress, anxiety, fatigue) occurred in the staff who experienced high work-stress rather than low workplace support, except in the case of depression. Alternately, adverse work outcomes (i.e., less organizational commitment and job satisfaction, more turnover

Table 3 . Mediator analysis (N = 201).

Table 4. Moderator analysis (N = 201).

Note: POS = Perceived organizational support. Stress = DASS’s stress scale.

Figure 1. Model of work-stress to psychological burden with organizational support and psychological stress (i.e., feelings of irritability and tension) as mediators; model explaining 91% of the variance in psychological burden.

intentions) tended to occur in the context of low workplace support. One interpretation of the results is that low workplace support alone was not sufficient to adversely impact on staff health, but it may have been sufficient to change the way staff felt about the organization. Alternately, the results may suggest that staff who had experienced high work-stress and distress and/or felt less supported by their organization (i.e., mediator) may feel less positively towards their organization, although we did not test this assertion. However, consistent with prior theory and empirical findings, we tested the work-support variables as possible moderators of these associations, as detailed below.

Regarding Hypothesis 2, psychological stress was found to fully mediate between high work-stress to worse anxiety, depression, and fatigue, and it partly mediated between high work-stress to greater turnover intentions, although it did not mediate between high work-stress to less organizational commitment or job satisfaction. The results are largely consistent with the small relevant literature suggesting that stressful work situations are likely to be perceived as stressful (i.e., psychological stress) and the perceptions may contribute to the development of anxiety, depression, and fatigue symptoms (Bourbonnais et al., 1999). However, this is the first study to explicitly examine whether psychological stress is a possible mediator of these associations. Taken together, the results suggest that the putative adverse impact of work-stress on psychological stress may help to explain the affective symptoms and fatigue seen in work-stressed staff, as well as their intention to leave the organization.

As for Hypothesis 3, POS and supervisor support did not moderate between high work-stress to less stress, depression, fatigue, and turnover intentions, and greater job satisfaction. These findings are largely novel, since no prior studies have examined POS and supervisor support as potential moderators of work-stress to staff health and work outcome associations. However, several analogous constructs have been examined in this regard, although the results are unclear as to the likely moderating role of workplace support between work-stress to psychological stress (e.g., Vermeulen & Mustard, 2000). Taken together, the results suggest that the moderate levels of perceived workplace support (i.e., POS, supervisor support) seen in this study were insufficient to reduce the putative adverse impact of work-stress on staff health (i.e., stress, anxiety, depression, fatigue) and work outcomes (i.e., organizational commitment, turnover intentions, job satisfaction), although the findings require clarification using a larger longitudinal study.

The results should be interpreted with caution given several study limitations. First, the sample was rather small and multiple analyses may have led to an inflation of the type I error rate, although an a priori power analysis indicated the sample was sufficient given the planned regression analyses. Second, participants were generally well-educated relative to the general population, with about half of the sample having some form of tertiary qualification. However, higher education levels are often reported in office-based staff (Motaz, 1986) and people who complete online surveys (Rubin & Babbie, 2010), suggesting the results may not be generalizable to workers with less control and/or autonomy in the workplace. Third, we used an anonymous survey approach in this study, thus we did not ask the participants to identify their workplace, so as to reassure them we could not divulge any identifying information to their work managers. However, for this reason, we were unable to identify the number and types of workplaces, or the approximate response rate, since most of the participants were recruited via email snowballing. Finally, these findings are only cross-sectional in nature and they were derived from a single sample which precludes making any causal inferences from the data. However, they may help build theoretical models that can be used to guide the design of longitudinal studies (Maxwell & Cole, 2007).

5. Conclusion

Work-stress was related to all adverse staff health outcomes (i.e., high psychological stress, anxiety, depression, fatigue) and most adverse work outcomes, except organizational commitment, in this office sample, and most of the associations were mediated by high psychological stress. In contrast, low workplace support (i.e., supervisor support, perceived organizational support, POS) was largely unrelated to staff health outcomes except depression, although it was related to the adverse work outcomes (i.e., turnover intentions, organizational commitment, job satisfaction). In addition, POS and supervisor support did not moderate between high work-stress to adverse staff health and work outcomes.

Taken together, the results suggest that high work-stress may have contributed to feelings of high perceived stress which then contributed to the development of adverse health outcomes, and greater intentions to leave the organization. In contrast, adverse work outcomes (e.g., job satisfaction, organizational commitment) tended to occur in the context of low workplace support, suggesting that a lack of workplace support may change the way a person feels about their organization without necessarily impacting on their physical or mental health.

References

- Akerstedt, T., Knutsson, A., Westerholm, P., Theorell, T., Alfredsson, L., & Kecklund, G. (2002). Sleep Disturbances, Work-Stress and Work Hours: A Cross-Sectional Study. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 53, 741-748. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00333-1

- Antony, M. M., Bieling, P. J., Cox, B. J., Enns, M. W., & Swinson, R. P. (1998). Psychometric Properties of the 42-Item and 21-Item Versions of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales in Clinical Groups and a Community Sample. Psychological Assessment, 10, 176-181. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.10.2.176

- Appels, A. (2000). Fatigue and Stress. In G. Fink (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Stress (Vol. 2 (A-Hi), pp. 108-110). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

- Bluedorn, A. C. (1982). A Unified Model of Turnover from Organizations. Human Relations, 35, 135-153. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/001872678203500204

- Bourbonnais, R., Comeau, M., & Vézina, M. (1999). Job Strain and Evolution of Mental Health among Nurses. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 4, 95-107. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.4.2.95

- Brotheridge, C. M., & Lee, R. T. (2005). Impact of Work Family Interference on General Well Being: A Replication and Extension. International Journal of Stress Management, 12, 203-221. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1072-5245.12.3.203

- Capizzi, J. A., Allen, G. J., Murphy, D., & Pescatello, L. S. (2010). The Interactive Effects of Metabolic Syndrome, Blood Pressure and Mental Health in Worksite Employees. Physician & Sportsmedicine, 38, 45-53. http://dx.doi.org/10.3810/psm.2010.04.1761

- Cavanaugh, M. A., Boswell, W. R., Roehling, M. V., & Boudreau, J. W. (2000). An Empirical Examination of Self-Reported Work-Stress among U.S. Managers. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 65-74. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.85.1.65

- Chen, C. C., & Chiu, S. F. (2008). An Integrative Model Linking Supervisor Support and Organizational Citizenship Behavior. Journal of Business and Psychology, 23, 1-10. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10869-008-9084-y

- Chiu, C. K., Chien, C. S., Lin, C. P., & Hsiao, C. Y. (2005). Understanding Hospital Employee Job Stress and Turnover Intentions in a Practical Setting: The Moderating Role of Locus of Control. Journal of Management Development, 24, 837-855. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/02621710510627019

- Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A Global Measure of Perceived Stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24, 385-396. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2136404

- Cropanzano, R., Howes, J. C., Grandey, A. A., & Toth, P. (1997). The Relationship of Organizational Politics and Support to Work Behaviors, Attitudes, and Stress. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 18, 159-180. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1099-1379(199703)18:2<159::aid-job795>3.0.co;2-d

- de Croon, E. M., Sluiter, J. K., Blonk, R. W. B., Broersen, J. P. J., & Frings Dresen, M. H. W. (2004). Stressful Work, Psychological Job Strain, and Turnover: A 2-Year Prospective Cohort Study of Truck Drivers. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89, 442-454. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.89.3.442

- Eisenberger, R., Huntington, R., Hutchison, S., & Sowa, D. (1986). Perceived Organizational Support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71, 500-507. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.71.3.500

- Ejaz, F. K., Noelker, L. S., Menne, H. L., & Bagaka’s, J. G. (2008). The Impact of Stress and Support on Direct Care Workers’ Job Satisfaction. The Gerontologist, 48, 60-70. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/geront/48.Supplement_1.60

- Erdogan, B., & Enders, J. (2007). Support from the Top: Supervisors’ Perceived Organizational Support as a Moderator of Leader Member Exchange to Satisfaction and Performance Relationships. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 321-330. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.2.321

- Folkman, S., Lazarus, R. S., Pimley, S., & Novacek, J. (1987). Age Differences in Stress and Coping Processes. Psychology and Aging, 2, 171-184. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.2.2.171

- Hammer, T. H., Saksvik, P. &OSLASH;., Nytrø, K., Torvatn, H., & Bayazit, M. (2004). Expanding the Psychosocial Work Environment: Workplace Norms and Work Family Conflict as Correlates of Stress and Health. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 9, 83-97. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.9.1.83

- Jamal, M. (2007). Job Stress and Job Performance Controversy Revisited: An Empirical Examination in Two Countries. International Journal of Stress Management, 14, 175-187. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1072-5245.14.2.175

- Kant, I. J., Bültmann, U., Schroer, K. A. P., Beurskens, A. J. H. M., van Amelsvoort, L. G. P. M., & Swaen, G. M. H. (2003). An Epidemiological Approach to Study Fatigue in the Working Population: The Maastricht Cohort Study. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 60, i32-i39. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/oem.60.suppl_1.i32

- Konrad, T. R., Williams, E. S., Linzer, M., McMurray, J., Pathman, D. E., Gerrity, M., Douglas, J. et al. (1999). Measuring Physician Job Satisfaction in a Changing Workplace and a Challenging Environment. Medical Care, 37, 1174-1182. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00005650-199911000-00010

- Kopp, M. S., Stauder, A., Purebl, G., Janszky, I., & Skrabski, A. (2008). Work-Stress and Mental Health in a Changing Society. European Journal of Public Health, 18, 238-244. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckm077

- Kottke, J. L., & Sharafinski, C. E. (1988). Measuring Perceived Supervisory and Organizational Support. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 48, 1075-1079. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0013164488484024

- Krupp, L. B., LaRocca, N. G., Muir-Nash, J., & Steinberg, A. D. (1989). The Fatigue Severity Scale: Application to Patients with Multiple Sclerosis and Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. JAMA Neurology, 46, 1121-1123. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archneur.1989.00520460115022

- Lovibond, S. H., & Lovibond, P. F. (1995). Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (2nd ed.). Sydney: Psychology Foundation of Australia.

- Maxwell, S. E., & Cole, D. A. (2007). Bias in Cross-Sectional Analyses of Longitudinal Mediation. Psychological Methods, 12, 23-44. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.12.1.23

- Motaz, C. J. (1986). An Analysis of the Relationship between Education and Organizational Commitment in a Variety of Occupational Groups. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 28, 214-228. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0001-8791(86)90054-0

- Mowday, R. T., Steers, R. M., & Porter, L. W. (1979). The Measurement of Organizational Commitment. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 14, 224-247. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0001-8791(79)90072-1

- National Occupational Health and Safety Commission (2010). Compendium of Workers’ Compensation Statistics Australia 2006-08. Canberra: National Occupational Health and Safety Commission.

- Pawlikowska, T., Chalder, T., Hirsch, S. R., Wallace, P., Wright, D. J., & Wessely, S. C. (1994). Population Based Study of Fatigue and Psychological Distress. British Medical Journal, 308, 763-766. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.308.6931.763

- Porter, L. W., Steers, R. M., Mowday, R. T., & Boulian, P. V. (1974). Organizational Commitment, Job Satisfaction, and Turnover among Psychiatric Technicians. Journal of Applied Psychology, 59, 603-609. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0037335

- Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS Procedures for Estimating Indirect Effects in Simple Mediation Models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 36, 717-731. http://dx.doi.org/10.3758/BF03206553

- Riolli, L., & Savicki, V. (2006). Impact of Fairness, Leadership, and Coping on Strain, Burnout, and Turnover in Organizational Change. International Journal of Stress Management, 13, 351-377. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1072-5245.13.3.351

- Rubin, A., & Babbie, E. R. (2010). Essential Research Methods for Social Work (2nd ed.). Belmont, CA: Cengage Learning.

- Schmidt, K. H. (2007). Organizational Commitment: A Further Moderator in the Relationship between Work-Stress and Strain? International Journal of Stress Management, 14, 26-40. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1072-5245.14.1.26

- Settoon, R. P., Bennett, N., & Liden, R. C. (1996). Social Exchange in Organizations: Perceived Organizational Support, Leader-Member Exchange, and Employee Reciprocity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81, 219-227. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.81.3.219

- Shore, L. M., & Tetrick, L. E. (1991). A Construct Validity Study of the Survey of Perceived Organizational Support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 76, 637-643. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.76.5.637

- Strazdins, L., D’Souza, R. M., Lim, L. L. Y., Broom, D. H., & Rodgers, B. (2004). Job Strain, Job Insecurity, and Health: Rethinking the Relationship. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 9, 296-305. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.9.4.296

- Thorsteinsson, E. B., & Brown, R. F. (2009). Mediators and Moderators of the Stressor-Fatigue Relationship in Non-Clinical Samples. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 66, 21-29. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.06.010

- Vermeulen, M., & Mustard, C. (2000). Gender Differences in Job Strain, Social Support at Work, and Psychological Distress. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5, 428-440. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.5.4.428

- Wada, K., Sakata, Y., Theriault, G., Aratake, Y., Shimizu, M., Tsutsumi, A., Tanaka, K., & Aizawa, Y. (2008). Effort-Reward Imbalance and Social Support Are Associated with Chronic Fatigue among Medical Residents in Japan. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 81, 331-336. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00420-007-0217-9

- Williams, E. S., Konrad, T. R., Linzer, M., McMurray, J., Pathman, D. E., Gerrity, M., Douglas, J. et al. (1999). Refining the Measurement of Physician Job Satisfaction: Results from the Physician Worklife Survey. Medical Care, 37, 1140-1154. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3767067

- Zhang, Y. J., Shi, Y. J., Wang, Z. Q. et al. (2005). Moderator Effect of Social Support and Coping Style on Relationship between Stress and Depression. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 19, 655-658. http://en.cnki.com.cn/Article_en/CJFDTOTAL-ZXWS200510004.htm

NOTES

*Equal contribution from each author.