Creative Education

Vol.5 No.4(2014), Article ID:43922,11 pages

DOI:10.4236/ce.2014.54037

The Conceptions of Integration of Tunisian Physical Education Cooperative Teachers and Student Teachers

Naila Bali1,2, Wadii Zayed1,2, Zied Hassen1, Souhail Hermassi1,2, Moktar Chtara1,2, Maher Mrayah1, Jean François Desbiens3

1High Institute of Sport and Physical Education, Ksar Saîd, University la Manouba, UMA, Tunis, Tunisia

2Tunisian Research Laboratory Sport Performance Optimization, Tunis, Tunisia

3Education Department, Sherbrooke University, Quebec, Canada

Email: naila.bali@laposet.net

Copyright © 2014 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 31 December 2013; revised 31 January 2014; accepted 7 February 2014

ABSTRACT

The behavior of cooperative teacher’s for integration into professional life was largely influenced by human relationships with other teachers and administrative staff. Firstly, our studies aimed to identify the interactions developed during the presence of cooperative teacher’s (CT) in the preparatory training for working life. Secondly, we ask to know how the masters of the course actually help to integrate training against the constraints that were imposed on his entourage. For this reason we base our analysis on a questionnaire consisting of ten questions that are the elements that make up the scale to clarify the latent construct “the integration of CT in professional life” and semi-directive interviews. The value of Cronbach alpha index is 0.772. Therefore, we can say that we get to this scale that consists of ten questions, satisfactory internal consistency. Our data were collected in the end of the course and interviews with ten physical education student teachers (PE-STs) at the Higher Institute of Sport and Physical Education (ISSEP) in Tunisia. They all mixed classes of Level 1 and 2 (first and second year of secondary school) teach. These interviews were semi-structured (30 minutes) and gave the PE-STs opportunity to distribute their views on major issues such as the satisfaction of the integration, management, as well as more succinct topics such as difficulties that occurred all along the path of integration. The data were analyzed using a constant comparison. However, three main issues have emerged of responses that illustrate the PE-STs’ satisfactions, and it’s their integration into working life, the definition of the objectives of the course and the role of CT (monitors and internship supervisor). This study revealed three major advanced by PE-STs conceptions: 1) the satisfaction of the integration (45%); 2) supervision (51.2%); and 3) knowledge of the objectives of the course (28.8%). The issues addressed in this paper will encourage educators to reflect on their own coaching practices and to include them in the process of accompanying PE-STs.

Keywords:Professional Recognition; Novice Teacher; Integration; Role and Status

1. Introduction

The teaching profession is a crossing between a partial experience, teaching under controlled conditions as an intern and the assumption of all the obligations of the real world of the classroom and the school.

Even if teaching is perceived as a determining experience both before practical teaching starts (Lortie, 1975; Weinstein, 1990; Bali, 2005), and during the teaching course (Britzman, 1991; Stoeber & Rennert, 2008; Bali, 2013), the actual entry stage is however important in developing a fuller and more realistic perception of teaching (Cochran-Smith, 2004) and in forming attitudes and perceptions of characteristics of the profession.

Previous research about the first year of teaching shows that the novice teachers are exposed to the complexity of the work of teaching, the broad variety of its roles, the big responsibility and devotion it involves, and the variety of people engaged in teaching profession.

The difficulties cited above and the conducts in which PE-STs manage with them form an undividable part of their early profession in school.

The work of Kyriacou, Avramidis, Høie, Stephens & Hultgren (2007) shows that future teachers displayed a degree of confidence to face their highest teaching skills after a year of teacher training at an early stage in the work, while Desbiens & al. (2013) reported that the effectiveness of organizational practices, leadership and management courses PE-STs plans motor commitment and discipline remain important challenges for trainees arrived after four years of training in PE-STs.

In contrast, Reeve (2002) regrets that the training programs of teaching focus primarily on conduct to better monitor student behavior to the detriment of ways to better support the development of autonomy and motivation self-determined. But, he also denounces the dominant school culture that values a teacher especially controlling model, which provides guidance and expects students to comply with its programs of action.

However, an internship is an opportunity to meet many typical situations that are not as many stimuli’s to the development of instruments of understanding of classroom situations and oneself as a teacher. Thus, the internship may contribute to the progressive building of a private law; know experience (Desbiens & al., 2013; Bali & al., 2013c). However, for many students, this is the most meaningful dimension of the teacher training program, the long appointed moment of learning to teach (Banville, 2002; Brown, 2004). However, for others, this is a very anxious time, a long “endurance test” marked by confusion in terms of setting expectations to meet, and to assume roles and functions to be performed (Kosnic, 2009). This is perhaps because they have often underestimated the complexity of the teaching practice.

From this reason some documentations and references consulted (Ria & Chaliès, 2003; Chaliès & Durand, 2000; Holvast, Wubbels, & Brekelmans, 1993) also indicate that sometimes internship experiences are marked by a low coherence because they pursue unclear objectives, they are poorly framed theoretically or they have shortcoming in terms of work planning and supervision provided by the host environment. The internship can be a way to “wash” the learning achieved in its training program and lose sight of the educational and social objectives pursued through the everyday actions of the teacher’s.

The text above highlight the central role of training in building skills to teach, while drawing attention to the fact that in the absence of conditions conducive to the learning and teaching activity the expected benefits have not been gained (Gauthier & al., 1997). Koster & al. (1998) reported that teacher’s associated persons are not always equipped to reinvest the concepts, theories and principles of the field of education in their works with students, which compromises the establishment of a sense of continuity between what is taught in the training program and the training environments (Mitchell & Schwager, 1993). Moreover, even when they manage to accurately assess the strengths and weaknesses of trainees, PEA tends to avoid critical remarks when weaknesses are recognized and recognize feel deprived when it comes to providing assistance trainees to overcome some specific problems (Spallanzani & Buckwheat, 1994).

In Tunisia, the university education aims to help PE-STs to integrate into working life (Bali & al., 2013b). For this reason the trainee is the central actor in his own training; it is not isolated to the master of the course but surrounded by teachers and in contact with the staff of the institution, with students and other colleague’s trainees. The role of the master course is the hold of the student, but a large number of actors involved, formally or informally, with his training. The difficult that PE-STs faced was how to integrate into the course by acting teacher and comply with its status as a student (Bali, 2013).

2. Methods

2.1. Study Protocol

This quantitative study explored the CT and the PE-STs’ perceptions about integration in teaching. It identified and describes the action and the advices communicated by the CT to help their PE-STs cope with the unruly Behaviors of their Pupils. In this section, we present the different steps of our methodological approach.

2.2. Procedure

Permission to conduct the current study by the University was Granted Institutional Review Board, the Tunisian Ministry of sports, the Principal of Higher Institute of sports and physical education (ISSEP) of Ksar Said in Tunis (Tunisia) (Manouba University). The researchers visited the CT and PE-STs dyads in their respective schools in order to present the purpose and design of the research and obtain written informed approval.

2.3. Participants

The participants in this empirical study were 80 PE-STs (40 men and 40 girls). All participated in this study were voluntarily. The CPs recruited were men and aged between 35 and 45 years old. Each of them had more than five years of experience in PE teaching and mentoring and had supervised one to three PE-STs.

The PE-STs had accepted to participate to this study were registered at ISSEP. All were young males (21 ± 1 years old) enrolled in an introductory course to professional life, what we call in Tunisia introductory course to practice pedagogy (introductory practicum applied to pedagogy), that share of the curriculum is of the last year of the Fundamental of Physical Education License. This professional learning activity was held in three high schools with mixed age classes (12 - 14 years old Pupils) of a rural area in Tunis. The activity lasted two semesters, four hours per week on Tuesday or Thursday for a cumulative total time of 116 hours of teaching.

Participants were not remunerated for participating in the research. They were not informed of the purpose and design of the research and written informed consent obtained from Each of Them. The research proposal approved by the ethics was board of Sports Ministry.

3. Data Collection Process and Technical

3.1. Procedure

First to start this work, the permission was granted by the Director of ISSEP Tunis and teachers to realize the current study. Then, the researcher collected the PE-STs, explained the stages of the study and the different questions in the questionnaire for PE-STs, oversaw the privacy and uniqueness of answers.

In this empirical study, the integration of PE-STs is studied in different schools during the 2013/2014 school year. First, we analyzed the responses of PE-STs. Then, we analyzed semi-structured interviews with ten PESTs. We used a sample of 80 PE-STs (40 girls, 40 boys) in ISSEP Tunis. These PE-STs (BAC +3) taught the class level 1 and 2 land in the school.

3.2. Participants

Participants in our empirical study were selected from total 80 PE-STs 220 PE-STs requested the Higher Institute of Sport and Physical Education (ISSEP) Tunis (there are only 3 ISSEP Tunisia each of which has its own modality of teaching practice). All PE-STs who participated in this study, taught in different academic institutions and studied in ISSEP is a public Higher Institute of Sport and Physical Education in Tunisia.

Participants were selected taking into account the location of the land relative to the school and the level taught. They were recruited from a single Higher Institute of Sport (Tunis). The sample of participants consisted of the PE-STs (third year, BAC +3) who taught Level 1 and 2 (first year of secondary school and second year). The choice of these criteria was because the PE-STs had a compulsory internship in the third year of study and teaching the same level. All participants agreed to start during an informational meeting. Participants were not informed of the purpose and design of the research and the choice of each. The research project was approved by the ethics committee of the Ministry of Sports.

3.3. Interview Procedure

A week later, the collection given the questionnaire conducted among PE-STs (step 1), a semi-structured interview staff was then performed. A pilot study was conducted with two PE-STs (girl and boy) to amend the articles in the issue of continuance before being carried out with each of these interviewed PE-STs. These interviews were conducted with ten PE-STs taken randomly from the sample of the ES (ISSEP) Tunis (step 2).

Given the nature of this research, all interviews with PE-STs were semi-structured interviews. According to the principles of the semi-structured interview (Mucchielli, 1976), the interview guide may vary slightly based on data collected by the questionnaire practices and daily life that these subjects questioned relations, but without deviating from the main topic. Duration was planned for 30 - 40 minutes, depending on the same considerations, the duration varied from subject slightly to another.

The interview contained open-ended questions following predetermined: 1) what are generally the designs of the PE-STs professional environment? 2) What are generally the designs of the course objectives? 3) What is the role of the coach and its contribution to the integration of PE-STs? 4) What is the attitude of the administrative staff and students? What are the difficulties encountered? All interviews were conducted at a convenient location for each participant, as the garden of the institute. All interviews were audiotaped with the consent of the participants.

We used a Dictaphone to record responses of the interviewed PE-STs. The questions focus on the everyday practices and relations PE-STs’ previously interviewed. PE-STs questioned while allowing them freedom of speech, they can express their opinions at their ease.

We then proceeded to suspended listening (step 3) audio recordings of semi-structured interviews after the questionnaire prepared individually for each PE-ST. Finally, we crossed the data collected during the first two stages.

3.4. Data Collection

The data were collected in two phases during 3 weeks of our project. The first is a pre-survey with the head of training to build up their biography data such as the number of PE-STs (male and female), places of training and/or location of the land in relation to the establishment school. Then, at a meeting, we presented the PE-STs various stages of this research displayed a presentation representing two phases of data collection.

They gave the student teacher’s an opportunity to share their views on major issues such as work, education and training as well as more succinct topics such as daily PE-STs and established relationships with various players in the school. Our data was analyzed using a statistic constant. Questions have been raised to show how integration in professional life of PE-STs’s influenced behavior, definition of objectives, the role of the coach and thoughts of the administrative staff.

4. Results

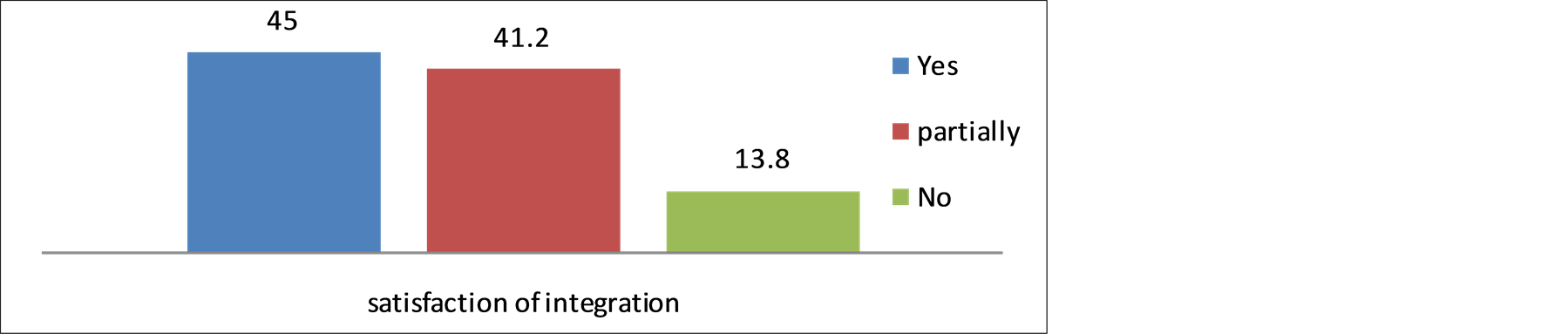

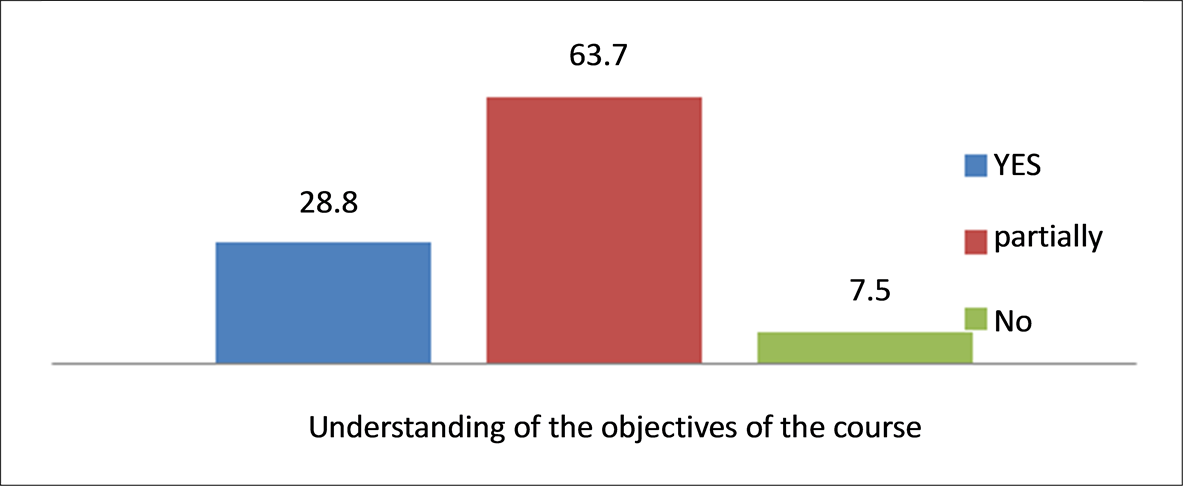

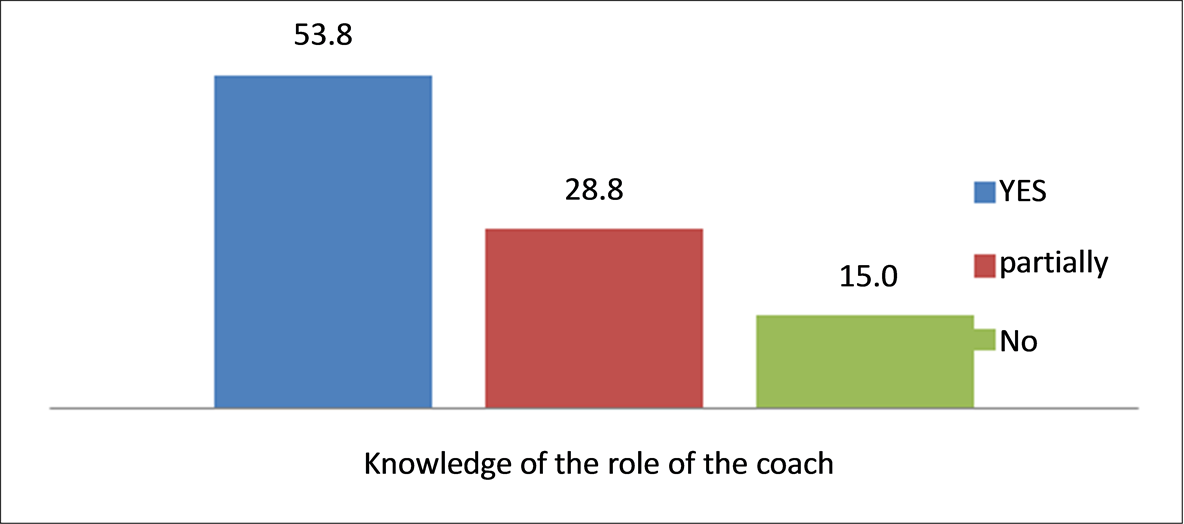

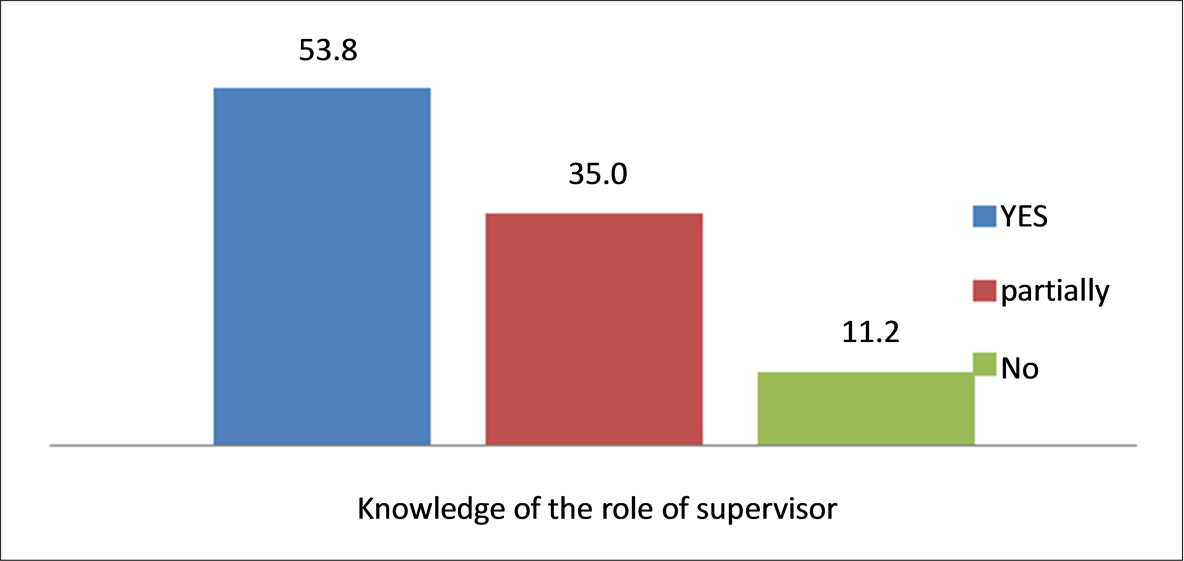

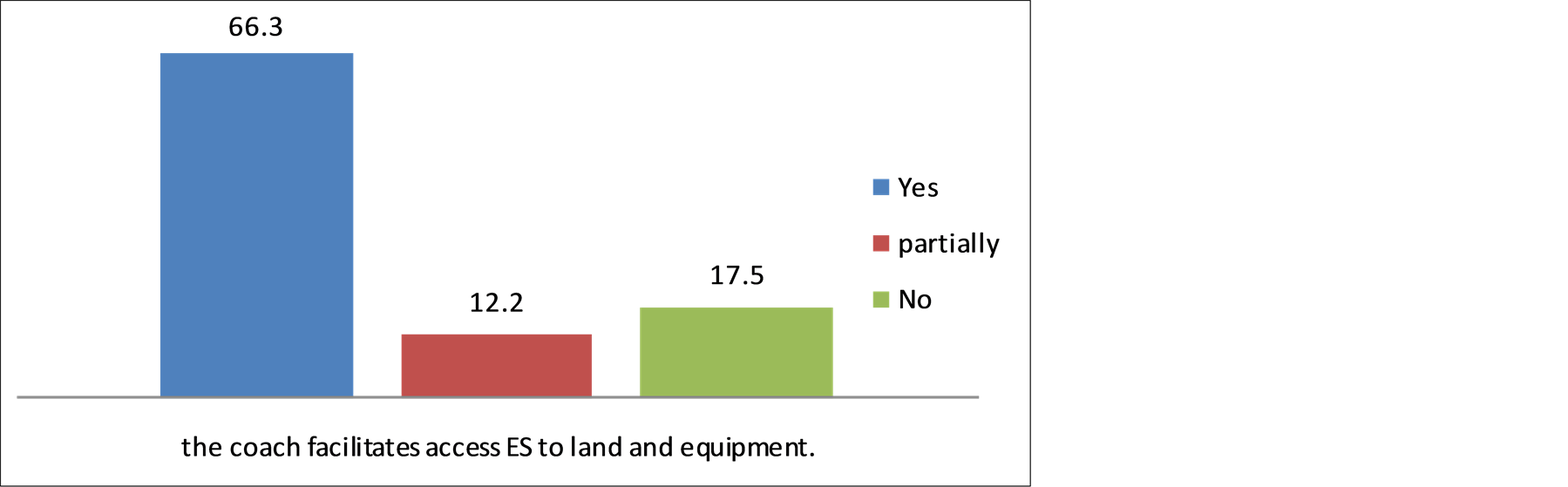

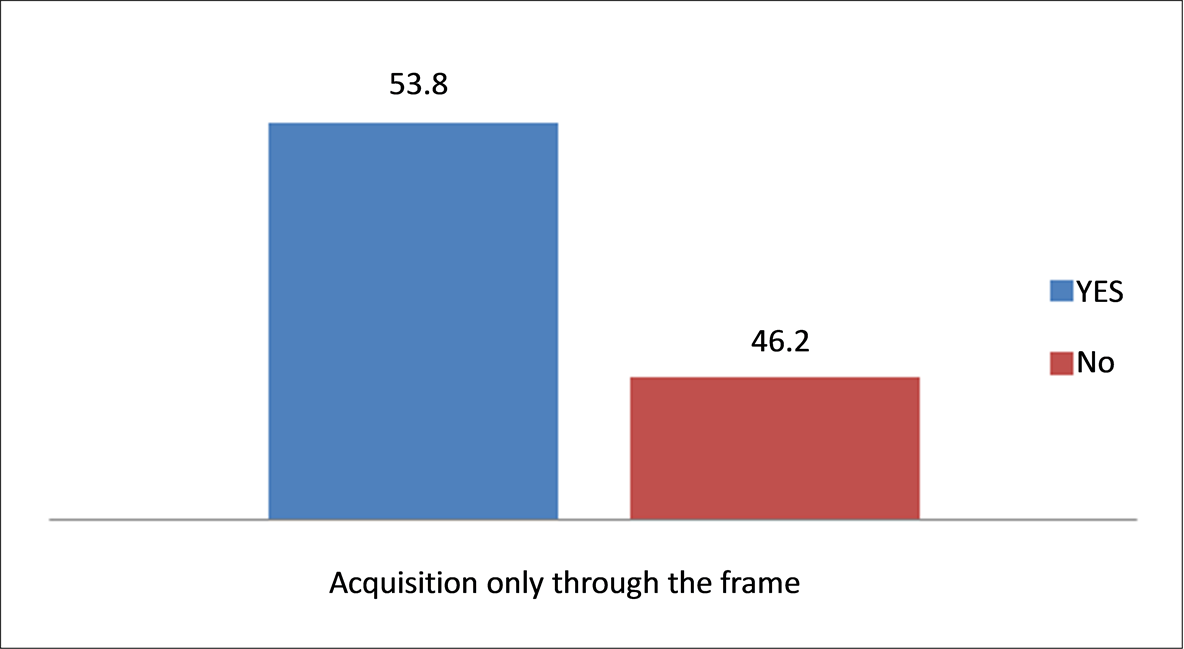

Ten conceptions used by PE-STs emerged from the data collected and were illustrated in Table 1: 1) satisfaction of integration (45%), 2) Understanding of the objectives of the course (28.8%), 3) Knowledge of the role of the coach (53.8%), 4) Knowledge of the role of supervisor (53.8%), 5) Satisfaction of coaching (51.2%), 6) Using the framer by boards (61.2%), 7) The coach facilitates the integration of PE-ST in the teaching staff (55%), 8) The coach facilitates the presentation of PE-ST students (43.8%), 9) The coach facilitates PE-ST access to land and material (66.3%) and 10) Acquisition only through the framer (53.8%).

The analysis of the results of the first question as shown in the Figure 1, confirms that PE-STs are either satisfied (45%) or partially satisfied (41.2%) depending on their integration into the school. The remaining PE-STs (13.8%) are not satisfied. The analytical study of the gender variable shows no significant difference between boys and girls (X2 = 1.85, P = 0.397, i.e. they have almost the same level of satisfaction).

They argue that teachers internship partially ease their integration within the school setting to learn: knowledge

Table 1. Data of responses of PE-STs’.

Figure 1. satisfaction of integration.

of students and administrative staff. The learning’s derived only exchange with the master course.

2) PE-STs argue either, as shown in the Figure 2, that the objective of the course have been defined (28.8%) or partially defined (63.7%). The remaining PE-STs (7.5%) argue that it have been incomprehensible. The analytical study of the gender variable shows no significant difference between boys and girls (X2 = 0.887, P = 0.642).

3) Data analysis of the third question (Figure 3) shows that (58.8%) of PE-STs declare that the role of the coach seems clear. however, (26.2%) consider it partially defined and 15% don’t know his role. The analytical study of the gender variable shows no significant difference between boys and girls (X2 = 2.566, P = 0.277).

4) Data analysis of the third question, (Figure 4) shows that (53.8%) of PE-STs declare that the role of the coach seems clear. however, (35%) consider it partially defined and 11.2% don’t know his role. The analytical study of the gender variable shows no significant difference between boys and girls (X2 = 1.595, P = 0.451).

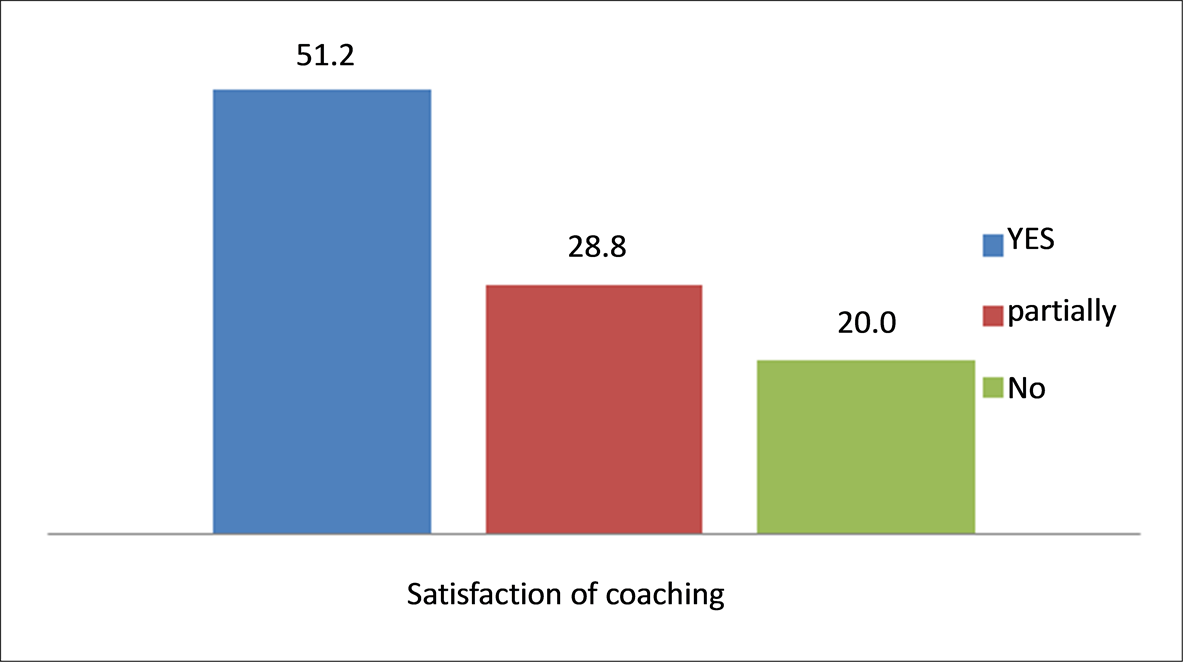

5) The most PE-STs (Figure 5) responded favorably satisfied (51.2%), partially satisfied coaching (28.8%) and the (20%) remaining are not. The analytical study of the gender variable shows no significant difference between boys and girls (X2 = 4.356, P = 0.113).

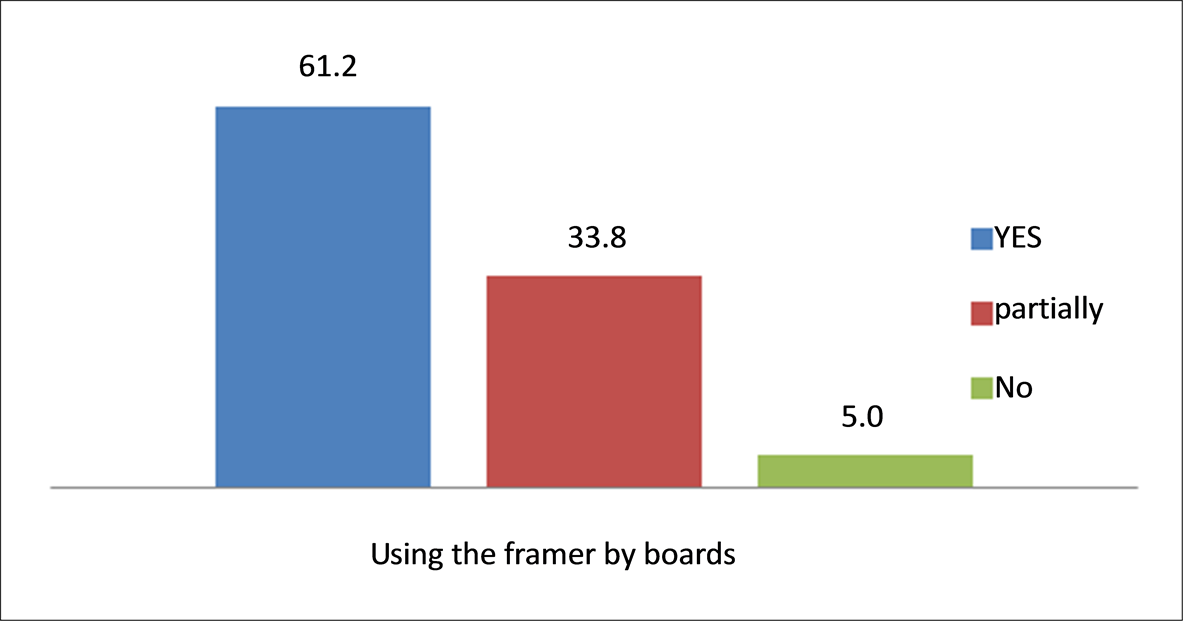

6) The study of the results of the sixth question (Figure 6) reveals that most PE-STs responded that the coach helps by advice (61.2%), helps partially by advice (33.8%) and only (5%) did not agree with them. The analytical study of the gender variable shows no significant difference between boys and girls (X2 = 1.057, P = 0.589).

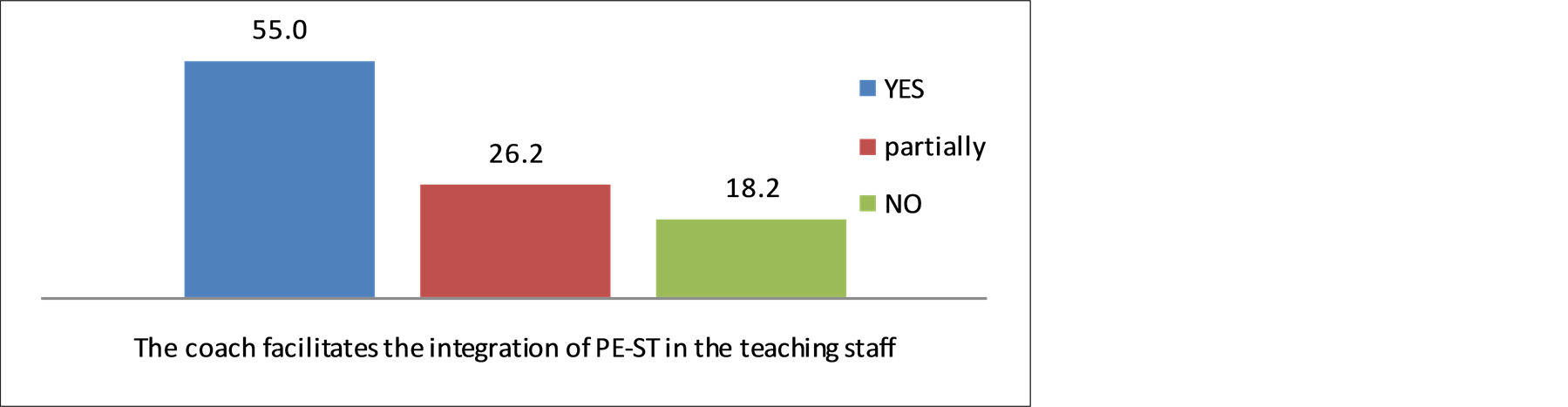

7) The analysis of the results of the seventh question (Figure 7) reveals that most PE-STs responded that the coach facilitates their integration into the teaching staff (55%) and partially (26.2%). However, the percentage of PE-STs that are not well presented is (18.8%). The analytical study of the gender variable shows no significant difference between boys and girls (X2 = 3.218, P = 0.200).

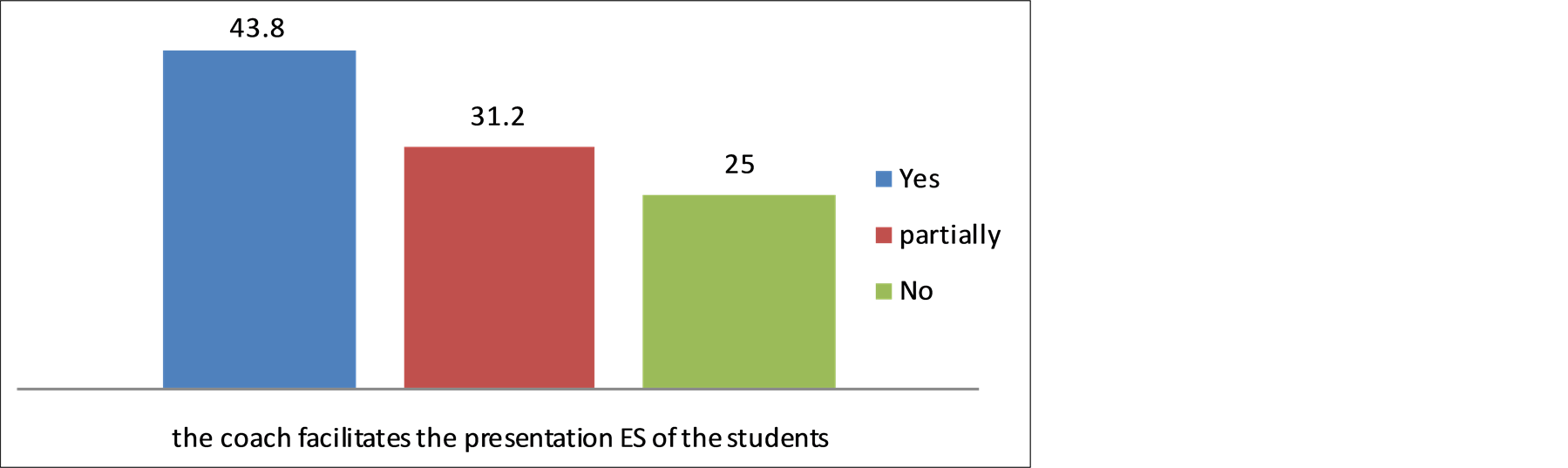

8) Analysis of the data collected from the eighth question (Figure 8) allows us to observe the role of the coach in the presentation of PE-STs. Thus, the percentage of PE-STs presented—Data analysis of the eighth question, allows us to see the role of the coach in the presentation of ES students. Thus, the percentage of ES are

Figure 2. Understanding of the objective of the course.

Figure 3. Knowledge of the role of the coach.

Figure 4. Knowledge of the role of supervisor.

Figure 5. Satisfaction of coaching.

Figure 6. Using framer by boards.

Figure 7. The integration of PE-ST in the teaching staff.

Figure 8. The coach role to present student teachers.

presented (43.8%) and partially presented (31.2%) and those are presented alone (25%). The analytical study of the gender variable shows no significant difference between boys and girls (X2 = 0.617, P = 0.734).

9) The results of the ninth question (Figure 9) indicates, according to the PE-STs, that (66.3%) agreed to partially agree and (16.2%) that the coach facilitates their access to access to sports fields. while (17.5%) say they use other means. The analysis study of the gender variable shows no significant difference between boys and girls (X2 = 3.133, P = 0.209).

10) Finally, we note (Figure 10) that the acquisitions are built only through the cooperative teacher, while the (46.2%) remaining seek the advice of others in the professional environment. The analytical study of the gender variable shows a significant difference between boys and girls (X2 = 11.314, P = 0.001).

5. Discussion

This study was focused on the PE-STs integration for professional life. The role of the cooperative teacher is accompanying PE-STs, but a large number of actors are involved, formally or informally, with his training.

Figure 9. Access to land and equipment.

Figure 10. Acquisition only through the framer.

Boudreau (2009) argues that the practical training program of teacher education in physical education can contribute significantly to the learning of future teachers. However, this learning often and much of the quality of supervision provided by tutors depends. Gal-Petitfaux (2010) adds that skills and knowledge related to the world of work and professional experience are now important since it complete skills and “academic “knowledge element. Better prepare students for the job they seek their input in the content of training qualifications aims.

These skills are of the order of a power to act and knowledge to be acquired in connection with the uses in the teaching profession. In our study, we present an important question: how the cooperative teachers help PE-STs to integrate into working life? To answer this question, we interviewed PE-STs and we found the following results.

Our data shows that PE-STs interviewed reported “satisfied” (45%), “Partially satisfied” (41.2%) and “not satisfied’’ (13.8%) of their integration. According to Perez-Roux (2007), the time of entry into the teaching profession is tricky from this point of view, to the extent that meet standards of training, initial representations trained and actual practices.

When they were asked about their integration into the school, some of them said:

“For the Master internship is prohibited rated my testimonials on the transcript.”

“They do not invite us to the class council because we are an intern.”

“I’m always on the field, the cooperative teacher had not introduced me to the administrative staff because I am a student, I feel like a guinea pig ...”.

Perez-Roux (2007), adds that professional socialization involves identifications others, roles to play, the discovery of explicit or implicit rules, taking into account an outdoor school student organization.

Portelance (2009), recall that the responsibility of teaching practicum supervision is entrusted to the cooperating teacher and supervisor training, respectively field trainer and university instructor, who perform their own roles in maintaining a focus on the professional development of future teachers. Among the questions posed, (58.8%) of PE-STs reflect the role of the cooperative teacher seems clear. Bujold (2002) stated that the role of the supervisor is to assist the student teacher in his school and putting to him available its class group for a specified time, trying to help him accomplish the transition to working life.... The term “supervisor” is that of “academic advisor” in France, “teacher-partner” (cooperating teacher) or “teacher-coach” in Anglo-Saxon countries (USA, Canada). (58.8%) of ES testify that the supervisor’s role seems clear.

According to Bujold (2002), the supervisor refers to a representative of the training institution - habitually a teacher—who plays the role of mediator between the tutor and the student teacher. In the form of a helping relationship, its task is to go, on time in training, to meet the dyad, to support advice and/or evaluate (p. 66). Vandercleyen & al. (2013) adds that supervises means “watch over” and is «the activity in which the person supervising guides, control and revise the work.” Hughes (1955) announced that the process should lead to recognition of the subject, both integrates professional group, and learned to play his role of personal and efficient manner (p. 2).

Indeed, most of the PE-STs (boys) receive information from their cooperative teacher. The girls ask advice from other CT and teachers.

We cited one of PE-ST declarative (Boy): “I asked for advice only to my framer ...”

And another PE-ST (Girl) had said: “I’m asking for advice from other coaches and teachers”.

“The advices of the other framer are more relevant, they often help me.”

However, few of PE-STs encountered difficulties in built with administrative staff. One of them said (Boy):

“For me, the administrative staff does not know me; they confused me with the students ...”

“The administrative staff called us interns; they don’t see that our role is also educational ...”

“They underestimate us; I am the first in the field and the last one to give an opinion ...”

PE-ST (Girl):

“For me, the CT has not introduced me to the administrative staff I knew all alone ...”

“The administrative staff does not know me; I want to know now or later. I do not know what they are ...»

Indeed, Vandercleyen & al. (2013) have three major evidences supervisory styles: directive, democratic and experiential reveals some invariants: a directive style, behavior assessment and instruction as well as the technical of communication as the main object of supervision. They show that the emotional experience of the trainee is not addressed head-on, but rather discretely or diverted, focusing on other objects of supervision.

According to Paquay (1996), the professionalism of a teacher is certainly characterized by mastering various “professional knowledge” (the knowledge taught, grids for analysis of situations, knowledge about the teaching procedures, etc.). But also by schemes of perception, analysis, decision making, planning, to mobilize its “knowledge” in a given situation. “Attitudes” necessary to the trade, such as the conviction of educability, respect each other, the knowledge of its own representations, control of emotions, openness to collaboration professional commitment.

According to Caron (2012), associate teachers provide some constructive feedback to their student and would hardly fit in offer. Under these conditions, it is important to consider the cognitive appropriation and integration of prescribed changes in management offered to trainees support to the development of professional skills.

Lebel & al. (2012) showed that support focus on developing self-confidence and sense of self-efficacy is likely to reduce failures and dropouts among students and therefore increase their enjoyment and perseverance in training and employability.

In this context, research has been the contribution of the associate teacher, training of trainee education. Portelance (2010) confirms that the expectations of cooperating teachers are high. He showed poor agreement between the perceptions of both partners of the dyad. It gives free rein to many questions about the relational dynamics within the dyad.

According to Perez-Roux (2011), the construction of teacher professionalism seems closely related to employability process. These two dimensions therefore require both integrate academic world with forms of socialization that are specific to it and professionalize formalizing experiential knowledge, analyzing practice, thinking about forms of transposition suited to public school.

Jorro (2007) proposes to add an ethical dimension to the organization of alternating integrative : the highest consideration of cultural, institutional, organizational, induces a greater involvement of the trainee and a relationship made multiple shoring, based on a process of pro-saver along beyond initial training.

In conclusion, to be a teacher does not just simply skills disciplinary order, whereas personal skills will do the rest as reported Feyfant (2010). It is not either consider that the teaching profession is learned on with the help, if necessary, experienced colleagues. Being a teacher is to be ferryman knowledge is to demonstrate the ten, fifteen or twenty competencies mentioned in official documents, Quebec, English, French or Belgian. But also be able to reflect on their practice, whether challenge, namely to question his expertise, his disciplinary knowledge and cultural convictions.

In this context, Rivard (2009) adds that one of the main challenges facing the initial training is undoubtedly that ensure the development of professional skills of future teacher, including probation. In this regard, it proposes to update the strategy preferred pedagogical supervision during internships: the triad (intern, cooperating teacher and university supervisor). Under these objectives are to deepen the representations of each of the actors in reference to the professional skills, describe the types of knowledge used to define favorable and supervision conditions. It reveals some differences surrounding representations and knowledge related to the supervision triad. Rivard (2009) has evidence the need for a common vision for professional development coupled with the relevance of views considered complementary between trainers is discussed.

6. Conclusion

The results of our study confirm that the difficulties cited above and the conducts in which PE-STs manage with them form an undividable part of their early profession in school.

It demonstrates the need for reflection on how the integration of PE-STs within schools hoping to find solutions to the constraints imposed on them in their professional environment. This requires reflection on the CP competence and intervention.

References

- Bali, N. (2005). “Theory and Practice” Articulation in the Training of Tunisian Student Physical Education Teachers. The Journal of Research and Training, 49, 135-150.

- Bali, N. (2013). Teachers’ Thought Processes: The Case of Tunisian Gymnastic University Teachers. Creative Education, 4, 77-84.

- Bali, N., & al. (2013a). Heterogeneity Language Conceptions’ Physical Education Teachers of the Fourth (4th) Year of Primary French Schools in Tunisia. IOSR Journal of Research & Method in Education (IOSR-JRME), 1, 77-84.

- Bali, N., & al. (2013b). The Proceed of Thinking Surrounded by Some French and Tunisian Gymnastic Teachers. IOSR Journal of Research & Method in Education (IOSR-JRME), 2, 17-24.

- Bali, N., & al. (2013c). The Conceptions of Authority of Tunisian Physical Education Cooperative Teachers and Student Teachers. Conference Proceedings of the 7th Biennial ARIS.

- Banville, D. (2002). Literature Review of Best Practices of Cooperating Teachers in the USA. Conference on Physical Education, Pékin, 16-19 Juillet.

- Boudreau, P. (2009). For a Model of Supervision of Inductive Training in Supervising Tutors in Physical Education. Education and Francophonie, 37, 121-139.

- Brown, J. (2004). Quarterely Report Pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. For the Quarterly Period Ended. September 24, 2004.

- Bujold, N. (2002). Pedagogical Supervision Overview. In Mr. Boutet, & N. Rousseau (Eds.), The Challenges of Teaching Practicum Supervision (pp. 9-22). Quebec PUQ.

- Caron, J., & Portelance, L. (2012). Ownership and Integration of Change in Education by Teachers Involved in Their Training Practices Trainees. Education and Francophonie, 40, 176-194. http://dx.doi.org/10.7202/1010152ar

- Chaliès, S., & Durand, M. (2000). The Utility Discussed Tutoring Training Initial Teacher Education. Research and Training, 35, 145-180.

- Desbiens, & al. (2013). What Influences the Verbal Class Participation of Students in the Teaching of Physical Education and Kinesiology. Canadian Journal of Higher Education, 43, 100-131.

- Feyfant, A. (2010). Learning Teaching Profession. Issues Brief VST (50).

- Gal-Petitfaux, N. (2010). Activity Classroom Teacher EPS and Character “Situated” Knowledge in Action: A Contribution to a Research Program in Cognitive Anthropology. Review eJRIEPS, 19, 27-45.

- Gauthier, & al. (1997). For a Theory of Pedagogy. Contemporary Research on the Knowledge of Teachers. Sainte-Foy (Quebec): Press Laval University.

- Jorro, A. (2007). The Alternation Research and Professional Training Ground. Research and Training, 54, 101-114.

- Lebel, C., Bélair, L., & Goyette, N. (2012). Support and Professional Service Perseverance Trainee’s Difficulties Recognition. Research & Educations, 7, 55-68.

- Lévesque, M., & Gervais, C. (2000). The Employability: A Step to Succeed in the Process of Professionalization of Teaching. Education Canada, 40, 12-15.

- Martineau, S., & Corriveau, G. (2000). Towards a Better Understanding of the Sense of Professional Incompetence among Teachers in Secondary Vocational Integration. Training and Profession, 6, 5-8.

- Martineau, S., & Presseau A. (2003). Sense of Professional Incompetence of Teachers and Early Career Support for Employability. Brock Education, 12.

- Moreau, J., & Villeneuve, L. (2006). Analysis of the Roles of Guardian Trainee Internship with Psychoeducation Three Quebec Universities. In: M. Fnenay, B. Raucent, & P. Wouter (Eds.), Question of Pedagogy in Higher Education (pp. 777-789). Belgium: Leuven University Press.

- Paquay, L. Altet, M., Charlier, E., & Perrenoud, P. (1996). Train Professional Teachers. What Strategies.

- Perez-Roux, T. (2006). Representations of Teaching and Training in Relation to Students STAPS Art: A Professional Identity Emerging. STAPS Review, 73, 57-69.

- Perez-Roux, T. (2007). Supporting Teachers in Initial Training. The View Formed on the Relationship Guardian Trainee. Research and Training, 55, 135-150.

- Perez-Roux, T. (2011). Change Careers to Become a Teacher: Professional Transitions and Dynamic Identity. Education Research, 11, 39-54.

- Perez-Roux, T. (2012). Identity Construction of New Teachers: What Recognition of Others to (Re)Known as a Professional? Educations & Research Journal, 7, 69-84.

- Portelance, L. (2009). Development of a Framework for the Training of Cooperating Teachers Quebec. Education and Francophonie, 37, 26-49. http://dx.doi.org/10.7202/037651ar

- Portelance, L. (2010). Analysis of Perceptions of Support from a Teacher Associated with the Formation of the Trainee. Education and Francophonie, 38, 21-38. http://dx.doi.org/10.7202/1002162ar

- Ria, L., & Chaliès, S. (2003). Emotional Dynamics and Activity: The Case of New Teachers. Research and Training, 42, 7-19.

- Rivard, M. C., Beaulieu, J., & Caspani, M. (2009). Triad: A Supervision Strategy to Redefine. Education and Francophonie, 37, 140-158. http://dx.doi.org/10.7202/037657ar

- Sudzina, M. R., & Knowles, J. G. (1993). Personal, Professional and Contextual Circumstances of Student Teachers Who “Fail”: Setting a Course for Understanding Failure in Teacher Education. Journal of Teacher Education, 44, 254-262.

- Vandercleyen, F., Delens, C., & Thornton, G. (2013). Supervisory Styles Masters Course in Physical Education: Taking Account of the Emotional Experiences of Trainees in an Interview Post-Lesson. Review e-JRIEPS, 61-98.