Open Journal of Social Sciences

Vol.06 No.10(2018), Article ID:88194,16 pages

10.4236/jss.2018.610014

Does the Employee’s Work Attitude and Work Behavior Have the Same Stability?

―A Empirical Study Based on Psychological Contract Breach

Biaobin Yan, Xiaoling Huang, Xueying Chen

School of Management, Guangdong University of Foreign Studies, Guangzhou, China

Copyright © 2018 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received: August 30, 2018; Accepted: October 27, 2018; Published: October 30, 2018

ABSTRACT

This study explored the mediating influence of organization commitment and organization support on the relation between psychological contract breach and work-related attitudes and behaviors of employees in 326 employees with questionnaires. The results show that: 1) Besides influencing job satisfaction directly, psychological contract breach doesn’t affect organizational identification and work behavior directly. 2) Organizational commitment and organization support not only all can partly play an intermediary role in psychological contract breach and job satisfaction, but also mediated fully the effect of psychological contract breach to organization identification. 3) By support commitment, psychological contract breach can affect the behavior of employees, such as personal initiative, interpersonal harmony, protection on company resources, altruistic behavior, in which organizational support plays a mediating role in psychological contract breach and organizational commitment. Conclusion: When employees perceive psychological contract breach, their work attitudes and behaviors will be different, and the mechanisms of the effects will also be different.

Keywords:

Psychological Contract Breach, Organizational Commitment, Organizational Support, Work-Related Attitudes and Behavior of Employees

1. Introduction

Modern society is a contract society, and the contract spirit exists in all aspects. Therefore, in recent years, psychological contract and psychological contract breach have received extensive attention from scholars at home and abroad. The psychological contract refers to the employee’s belief system that employees are based on their own relationship with the organization, based on commitment and perception, and the responsibilities and obligations formed by themselves and the organizations. Psychological contract breach refers to the employee’s subjective perception of an organization’s failure to perform one or more responsibilities in return for the employee’s contribution in the psychological contract. It is also the employee’s cognitive assessment of an organization’s fulfillment of the psychological contract (Morrison & Robinson, 1997) [1] . Psychological contract breach is an indispensable part of the study of psychological contract theory. A large number of studies have found that psychological contract is a psychological bond and the internal force to maintain and develop the relationship between organizations and employees. It has a significant impact on employees’ work-related attitudes and behaviors, which has become the consensus of researchers (Zhang Shumin, 2011) [2] . At the same time, the conclusions on the psychological contract breach are much more complicated. Previous studies on psychological contract breach mainly focused on: 1) what the outcome variables are that will be affected by psychological contract breach; 2) the discussion on whether there exist some variables―regulating or mediating variables that play a role in the relationship between the psychological contract breach and its outcome variables? If the answer is yes, what are these variables and how do they work?

What are the outcome variables that will be affected by psychological contract breach? Scholars have reached consensus; that is, the emotional response and work-related attitudes and behaviors of employees (Zhao Xin et al., 2015; Shi Jing et al., 2011) [3] [4] . Emotional response refers to the emotional experience of employees due to strong work events (such as psychological contract violation and distrust) (Zhao, Wayne, et al., 2007) [5] . Work-related attitude is the general evaluation of the employees toward their employers and the work. The representative indicators include job satisfaction, organization commitment of employees, organization identification, turnover Intention, etc. Work behaviors are employee responses to work-related content. The representative indicators include organizational citizenship behavior, in-role behavior, anti-citizenship behavior, deviant behavior, etc. (Chiu & Peng, 2008) [6] . These indicators have continued to attract the interest of scholars.

Scholars also give the affirmative answer on whether there exist some variables that play a role in the relationship between the psychological contract breach and its outcome variables? But there are some different opinions on what specific variables are and how they work. Some studies have found that psychological contract breach exerts impact on employees’ emotions, attitudes and behaviors, on which a series of variables have moderating effect. After carding, Shi Jing and Cui Lijuan (2011) pointed out that personal traits (such as personality, fairness sensitivity, self-control, achievement motivation, attribution style, self-service bias, etc.) are important regulating variables. Perception (such as procedural fairness, organizational political perception, leadership member exchange, distribution fairness, communication fairness, etc.), as well as environmental factors, organizational reasons for the destruction of the contract, employment contract type (Fan Wei, Ji Xiaopeng, Shao Fang, 2011), etc. are also important regulating variables [7] . Some other scholars pointed out that there exist some mediating variables that play a role in psychological contract breach’s impact on employees’ work-related attitudes and behaviors, such as employees’ trust in the organization, unmet expectations of employees, organizational cynicism, organizational support and leadership-subordinate exchange (Shen Yimo, Yuan Denghua, 2007), etc. [8] . The reason why there are two different views is that the impact of psychological contract breach on employee attitudes and behaviors is really complex, which is also the reason why it can continuously attract the interest of researchers. It is also an important starting point for this study. In addition, we believe that there may be another reason for this difference. That is, in the past, many of the previous studies, when examining the relationship between psychological contracts and employees’ attitudes and behaviors, either choose a single attitude or a behavioral variable, or choose a single intermediate variable (such as self control, achievement motivation, leadership exchange, etc.). As Restubog et al. (2009) pointed out, some researchers focus on the regulation of individual variables, while others focus on the regulation of context variables [9] . Very few interactive perspectives are used.

This study attempts to answer the above two questions: First, when the employee’s psychological contract breach is generated, will his work-related attitudes and work behaviors be both affected, and will the performance be different? Second, what are the mechanisms of the effects of the psychological contract breach on employees’ work-related attitudes and work behaviors, and are the mechanisms of the effects on work-related attitudes and work behaviors different?

2. Theory and Hypothesis

2.1. Psychological Contract Breach and Work-Related Attitudes and Behaviors

This study selected three indicators of job satisfaction, organizational identification, and organizational citizenship behavior as the outcome variables of psychological contract breach. The first two variables are indicators of work attitude, and the latter variable is an indicator of work behavior.

Job satisfaction is the pleasure that people get from his job. Tekleab (2005) found that employees’ job satisfaction will increase if psychological contract is effectively fulfilled, but it will decrease when psychological contract is breached [10] . Organizational identification means that members of an organization are consistent with the organization they join in behavioral concepts, feel that they have both a rational contract and a sense of responsibility in the organization, as well as an irrational sense of belonging and dependence, and thus behave responsibly in all kinds of organization activities on this psychological basis. Many studies have shown that when employees feel that the psychological contract is breached, their organizational identification will be reduced (Restubog et al., 2009). Organizational citizenship behaviors (OCB) refer to employees’ behaviors that are beneficial to the organization while have not been explicitly or directly confirmed in the organization’s formal compensation system. Many studies have found that the psychological contract breach will reduce organizational citizenship behavior of employees (Zhao Lei, Shen Yimo, Wei Chunmei et al., 2011) [11] . To this end, we propose the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 1: Psychological contract breach is significantly negatively correlated with job satisfaction, organizational identification, and organizational citizenship behavior.

2.2. The Mediation Role of Organizational Commitment and Organizational Support

Organizational commitment and organizational support are two important indicators for assessing the relationship between individuals and organizations. Organizational commitment refers to employees’ attitude, recognition, commitment, responsibility and obligation to the organization. Organizational support refers to employees’ overall perception and faith in how the organization views their contribution and cares about their interests.

Many studies have shown that psychological contract breach can affect organizational commitment. For example, Restubog (2009) found that psychological contract breach reduces the organizational commitment of employees. This conclusion has been supported by domestic scholars (Tian Haifeng, Liu Zezhao, Wang Huijun, 2015) [12] . Restubog (2009) further explained that employees reduce the organizational commitment by reducing their emotional commitment to the organization. Similarly, researchers have confirmed the close relationship between psychological contract and organizational support. For example, Aselage and Eisenberger (2003) found that when employees perceive that the organization fulfills the psychological contract well, they will cultivate a higher sense of organizational support; but when they think that the psychological contract is breached, then their sense of organizational support will be significantly reduced [13] .

Other studies have pointed out that organizational commitment and organizational support have a significant impact on employees’ work-related attitudes and behaviors. For example, many studies have found that organizational commitment has correlation with employees’ voluntary turnover behavior, employee’s intention to actively seek other jobs and employees’ turnover intention, the average coefficient of which is −0.227, −0.464 and −0.599 respectively(Hu Weipeng, Shi Kan, 2004) [14] . Similarly, organizational support can effectively predict employees’ job satisfaction, organizational citizenship behavior, absenteeism and turnover intention.

Hypothesis 2: Psychological contract breach affects employees’ work-related attitudes and behaviors through mediation of organizational commitment of employees. Organizational commitment plays a mediating role.

Hypothesis 3: Psychological contract breach affects employees’ work-related attitudes and behaviors through mediation of organizational support of employees. Organizational support plays a mediating role.

In addition, studies have shown that organizational support is closely related to organizational commitment. Zhao and Wayne (2007) found that the more the employees perceive support from the organization, the more emotional commitment they will have. The research of Liu Xiaoping and Wang Chongming (2002) also reached the same conclusion [15] . Eisenberger (2001) further explained that when employees perceive more support given by the organization, employees will have the obligation to repay the organization based on the principle of reciprocity, thereby enhancing the organizational commitment [16] .

Hypothesis 4: Organizational support affects employees’ work-related attitudes and behaviors through mediation of organizational commitment. Organizational commitment plays a mediating role.

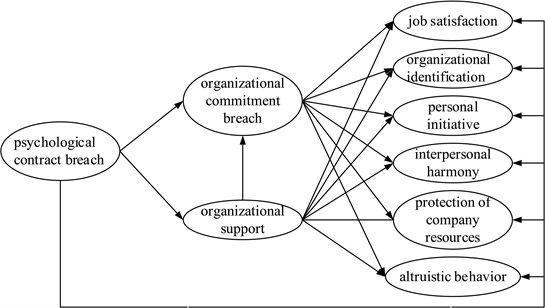

Based on the above four hypotheses and the previous research, we propose a hypothesis model (as shown in Figure 1) and carry out a test.

3. Methods

3.1. Research Object

The survey was conducted among a number of universities, institutions and enterprises in Guangdong Province such as South China University of Technology, Guangdong University of Foreign Studies, China Mobile Guangzhou Branch et al., in the form of mail surveys and on-site questionnaires. With the assistance of staff of personnel departments of universities and institutions as well as enterprises, questionnaires were distributed to the staff. A total of 380 questionnaires were distributed, 354 questionnaires were returned. The total valid questionnaires were 326, excluding 28 incomplete and invalid questionnaires. The effective

Figure 1. A hypothesis model.

recovery rate was 85.8%. Among the returned questionnaires, 159 were males, accounting for 48.8%; 167 were females, accounting for 51.2%; 203 were from 20 to 29 years old, accounting for 62.3%; 83 were from 30 to 39 years old, accounting for 25.5%, and 40 were over 40 years old, accounting for 12.2%. In terms of education background, 163 have a junior college degree or below, accounting for 50.0%, 117 were bachelors, accounting for 35.9%, 46 were masters, accounting for 14.1%; 83 were managers, accounting for 25.5%; 243 were non-management employees, accounting for 74.5%. In terms of working years, the number of people who have working life of under 5 years, 5 - 10 years and over 10 years is 231, 52 and 43, accounting for 70.8%, 16.0% and 13.2% respectively. The results are shown in Table 1.

3.2. Research Tools

1) Psychological Contract Breach Scale. This study draws on Psychological Contract Breach Scale used by Robinson and Morrison (2000) [17] . The respondents need to score on five items such as “So far, almost all the commitments the company made while recruiting me have come true”. In the original scale, Cronbach’s α = 0.89, and hereof the measured α = 0.84.

2) Organizational Support Scale. This study refers to the practice of Shen Yimo (2007) and eight items in the scale compiled by Eisenberger (1990) were selected, such as “When I need help, the company will help me”. The original scale Cronbach’s α = 0.87, and hereof the measured α = 0.90.

3) Organizational Commitment Scale. The three-dimensional organizational commitment scale developed by Allen and Meyer (1990) [18] , including eight items such as “I am very happy to grow with the company” was adopted in this study. The original scale is of good reliability and validity (Allen & Meyer, 1990). And hereof the measured α = 0.88.

4) Job Satisfaction Scale. This study is planned to use the general satisfaction measure in the Job Diagnostic Survey developed by Hackman and Oldham (1974) [19] , including five items, such as “Overall, I am very satisfied with my work.” The original scale Cronbach’s α = 0.77, and hereof the measured α = 0.88.

5) Organizational Identification Questionnaire. This study used the OIQ

Table 1. Sample data distribution (N = 326).

Questionnaire (Organizational Identification Questionnaire) (Mael and Ashforth, 1992) [20] . The questionnaire contains six items such as “I really want to know how other people think about my company.” The original scale Cronbach’s α coefficient is 0.84, and hereof the measured α = 0.83.

6) Organizational citizenship behavior scale. This study draws on the Chinese Organizational Citizenship Scale compiled by Jiing-Li Farh et al. (2002) [21] , and selects four dimensions of altruistic behavior, personal initiative, interpersonal harmony and protection of corporate resources. The Cronbach’s α coefficient is 0.89, 0.82, 0.86, 0.81. The α of the four dimensions of this measurement are 0.83, 0.88, 0.85, and 0.81, respectively.

The scales in this study are all 7-point scales, with 1 being completely opposed and 7 being completely agreed. The original scale is mainly designed for corporate employees, so we replace the word “company” with the word “unit” in the scales issued to colleges and institutions. In order to ensure the measurement equivalence of the English version of the above scales and the Chinese version, we translated the scales of English version into Chinese and then translated the Chinese version into English until the retroversion questionnaires make no difference, adopting the common method applied in cross-cultural researches.

3.3. Methods of Data Collection and Analysis

SPSS17.0 and LISREL8.7 were used to conduct statistical analysis in this study.

4. Results

4.1. Common Method Bias Test

In order to minimize the impact of common method bias, we collect data in the forms of both online surveys and on-site field surveys, emphasizing confidentiality and anonymity. The data is only used for scientific research. At the same time, in the data analysis, we adopted a common practice, Harman’s One-factor Test, which means that non-rotating principal component analysis on items of all variables was conducted at the same time (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, 2003) [22] . At the time of analysis, if multiple factors are obtained and the first factor accounts for variation of no more than 40%, then the common method variation problem is not serious. The results of non-rotating principal component analysis of this study showed that the eigenvalues of nine factors were greater than 1, and the first factor accounted for variation of only 19.14%. Based on this, we believe that the common method variation problem of this study is not serious.

4.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis Results

To confirm the relationship between the nine variables involved in the study, we carried out confirmatory factor analysis. According to the theoretical deduction, we analyze three kinds of models: nine factor model, single factor model and six factor model. The results are shown in Table 2.

From Table 1, it is not difficult to find that the fitting condition of the nine factor model is the most ideal. The results showed that there is good discriminant validity among the nine variables. This provides an important guarantee for the following analysis.

4.3. Descriptive Statistics of Each Scale

We analyzed the mean, standard deviation, and correlation coefficients among variables (see Table 3). As mentioned above, the scales used in this study are all seven-point scales with an average score of 3.5 points. The results showed that except the psychological contract score (M = 3.530, SD = 1.413), the scores of other dimensions are higher than the average score. It is also not difficult to find that psychological contract breach, organizational support, organizational commitment, job satisfaction, organizational identification, altruistic behavior, personal initiative, interpersonal harmony, and the protection of corporate resources are correlated significantly (r from 0.134 to 0.673). This result provides a necessary premise for the subsequent mediating effect test.

4.4. Comparison of Structural Equation Models

To test the mediating effect between organizational support and organizational commitment, this study draws on the practices of Shen Yimo (2007), comparing the Benchmark Model (full mediation model, as shown in Figure 1) with the other two competitive models (partial mediation model and modified partial

Table 2. Confirmatory factor analysis results (N = 326).

Table 3. Mean, standard deviation and Pearson correlation coefficient of each scale (N = 326).

*All the correlation coefficients are significant when they are up to p < 0.01 or ***p < 0.001.

mediation model). Finally, the mathematical model of winning probability with better fitting of data is applied and the results are as shown in Table 4.

The comparative study found that the difference between Model one and Model two was not significant (△χ2 = 33.89, p > 0.05). According to the principle of parsimony, model two is first excluded, and model one with fewer paths is taken. It shows significant difference between the two models after comparison (χ2 = 22.370.89, p < 0.01), and model three is better than model one. As can be seen from Table 3, in this model, χ2 = 1775.760, df = 834, χ2/df = 2.129, NNFI = 2.070, CFI = 0.900, RMSEA = 0.052 (less than 0.08). The paths that reflect the relationships among the variables are shown in Figure 2.

It can be seen from Figure 2 that in the employee’s work-related attitudes and behaviors variables, 1) the psychological contract breach has direct impact on only the employee’s job satisfaction (β = −0.35, p < 0.01); 2) organizational commitment has direct impact on six variables: job satisfaction (β = 0.49, p < 0.01), organizational identification (β = 0.34, p < 0.01), altruistic behavior (β = 0.38, p < 0.01), individual initiative (β = 0.52, p < 0.01), interpersonal harmony (β = 0.25, p < 0.01) and protection of company resources (β = 0.44, p < 0.01); 3) organizational support has direct impact on only job satisfaction (β = 0.33, p < 0.01) and organizational identification (β = 0.41, p < 0.01). At the same time, 4)

Table 4. The comparative result s of structural equation models (N = 326).

Note: Model 1: Full mediation model (as shown in Figure 1). Model 2: On the basis of model 1, the paths through which psychological contract breach affects six dependent variable indicators such as job satisfaction were increased. Model 3: On the basis of model 2, the paths through which psychological contract breach and organizational support affect organizational identification were decreased.

Figure 2. The paths that reflect the relationships among the variables.

psychological contract breach has indirect impact on employees’ work attitudes and behaviors by affecting organizational commitment and organizational support; 5) organizational support has indirect impact on six variables such as employees’ work behaviors and work attitudes etc. through mediating effect of organizational commitment.

5. Discussion

Many studies have shown that the study of psychological contract breach has important theoretical and practical significance. For example, many studies have shown that psychological contract breach has an important impact on employee’s emotional, attitude and behavioral research (Rosen C C, Chang C H, Johnson R, 2009) [23] . Other studies have shown that psychological contract breach has a significant impact on the study of trade union relations (Li M and Zhou L, 2015) [24] , and the relationship between customers and enterprises in the field of marketing (Zhao X, Ma Q, 2015). Since the psychological contract breach sense is a subjective perception of employees, it can occur to them even when the breach doesn’t really happen. Therefore, as long as employees generate the belief that the “contract has been breached”, regardless of whether the belief is reasonable or not and whether it does really happen or not, the belief may affect the behavior and attitude of employees. At the same time, the emergence of employees’ psychological contract breach is common. Zhang Shumin (2011) summarized the reasons: first, the organization intends to default; second, the organization is unable to fulfill the promise; third, the contractual parties have inconsistent understanding of commitment or responsibility. These factors may accelerate the research process of psychological contract breach.

In the past, it is common for scholars to discuss the post-discipline variables of psychological contract breach. The relationships between psychological contract breach and job satisfaction, Organizational identification, intention to leave, organizational citizenship behavior have been studied while it’s rarely the case that attitude and behavior are taken as the resulting variables. Moreover, the two variables, individual commitment to the organization (organizational commitment) and organization’s commitment to the individual (organizational support) are introduced to reveal its mechanism of action, which undoubtedly is important reference for theoretical research and management practice of psychological contract breach.

5.1. The Effect of Psychological Contract Breach

The results of this study show that psychological contractual breach has a direct impact on only job satisfaction, which gives support to the research of Tekleab (2005); however, it has no direct impact on Organizational identification and personal initiative and other work behaviors. This conclusion is inconsistent with many studies in the past (Rosen et al., 2009; Qian Shiru et al., 2015) [25] . At the same time, this finding is not so much in agreement with the view of the social exchange theory that explains the psychological contract. According to the theory of social exchange, there is an exchange relationship between employees and organizations, based on the principle of reciprocity. Therefore, when an employee perceives that the psychological contract is fulfilled, he feels that his or her contribution has been rewarded, and accordingly the organization should be rewarded (for example, more organizational citizenship behaviors). Conversely, when the psychological contract is breached, the employee’s efforts don’t pay off, and they pursue psychological balance by reducing organizational citizenship behaviors (Suzanne, Lewis, & Taylor, 2000) [26] . We believe that this inconsistency arises from the fact that the relationship between psychological contract breach and employees’ work attitudes and behaviors is indeed extremely complex, and this relationship is affected by many other factors. In addition, some of our samples are college teachers, which may also have a partial impact on this outcome. Shi Ruokun (2011) found through in-depth interviews that when college teachers’ psychological contracts were breached, they rarely resort to revenge such as negative absenteeism and attacks on schools, and the majority of them mainly complain [27] . In other words, when psychological contract breach occurs, their job satisfaction may be reduced, but their work behaviors will not become negative.

5.2. Relationship between Organizational Commitment, Support and Work-Related Attitudes and Behaviors of Employees

This study takes emotional commitment as an indicator of organizational commitment, based primarily on the three-dimensional theory proposed by Allen and Meyer (1990). It includes three dimensions: continuous commitment, normative commitment, and emotional commitment. Among them, emotional commitment refers to the individual’s recognition and relationship to the organization’s goals and values, and the individual’s emotional experience to the organization brought about by this kind of recognition and relationship. Previous studies have found that among the three types of commitments, emotional commitment has the optimal impact on employees’ work attitudes (Carmeli & Freund, 2004) [28] . This is another important reason why we choose emotional commitment as an indicator of organizational commitment.

The study found that organizational commitment has direct impacts on employee’s work-related attitudes (job satisfaction and Organizational identification) and work behaviors (individual initiative, interpersonal harmony, protection of entity’s resources and altruistic behavior), which supports the researches of Hu Weipeng (2004) and other people. Their research confirms that organizational commitment has impacts on employees’ work attitudes and behaviors. The study also found that organizational support has direct impacts on work attitudes (job satisfaction and Organizational identification), and has indirect impacts on work behaviors (individual initiative, interpersonal harmony, protection of entity’s resources and altruistic behavior), realized by affecting organizational commitment, which plays a wholly mediating role. There has been some controversy over this result: one view is that organizational support can predict work such as job satisfaction and turnover intentions and will also have impact on organizational citizenship behaviors and absenteeism rates; Another point of view is that the relationships between organizational support and employees’ work-related attitudes and behaviors are affected by some mediating variables. For example, studies have shown that employees with high organizational support will have higher job satisfaction, more positive emotions, more active work commitment, stronger willingness to stay, and more off-character work performance, while have lower tension and less withdrawal behavior under the impact of the mediating variables (Coyle-Shapiro, 2000) [29] . Obviously, this controversy suggests that researches on organizational support need to be further carried out. At the same time, organizational commitment also partially mediates the relationships between organizational support and work-related attitudes, which also reminds us that organizational commitment plays an important part in the relationships between organizations and individual.

5.3. Mediating Effect between Organizational Support and Organizational Commitment

This study found that psychological contract breach’s effect on employees’ work related attitudes (job satisfaction and organizational identification) is mediated by organizational commitment and organizational support, which supports the view of Aselage and Eisenberger (2003). They believe that when an organization fulfills the psychological contract well, the employees’ organizational support will be further enhanced, thereby their work attitudes (such as increasing willingness to stay and Organizational identification) will be improved, and they will double efforts to help the organization achieve its goals; on the contrary, when psychological contract breach occurs, the employee’s organizational support will also decrease accordingly, which will lead to the crisis of organization identification and reduce employees’ willingness to stay. In addition, this study also found that in the relationships between psychological contractual breach and work behaviors (individual initiative, interpersonal harmony, protection of unit resources, altruistic behavior), organizational commitment plays a mediating role, but the mediating effect of organizational support is not significant. This result is consistent with that of the research conducted by Shen Yimo (2007). We believe that organizational support and work attitudes tend to be in the scope of cognitive evaluation. Therefore, organizational support mediates the relationships between psychological contract breach and the attitudes of employees, but the mediating effect on the relationship between psychological contract breach and employees’ work-related behaviors is not significant. This study also reveals the importance of organizational commitment. Organizational commitment not only mediates the relationships between psychological contract breach and employees’ work behaviors, but also mediates the relationships between organizational support and work-related behaviors.

In fact, organizational commitment and organizational support are a kind of promise in terms of connotation, except that the former emphasizes individual commitment to the organization, while the latter focuses on organizational commitment to individuals (Eisenberger & Huntington, 1986), and the relationships between the two have also been confirmed many times (Liu Xiaoping, Wang Chongming, 2002). However, this study reveals a very interesting phenomenon. In the relationships between psychological contractual breach and employees’ work attitudes and behaviors, the mediating role of organizational commitment is different from that of organizational support, and the mediating effect of organizational commitment is more prominent. We believe that the current labor law can partially explain this phenomenon. The formal equality in labor relations stipulated in the Labor Law contradict practical inequality. Laborers and labor organizations are actually in an unequal position in many labor relations. Therefore, the behaviors of employees are mainly affected by their own and their tolerance for the organization’s contract breach and other non-fulfilling commitments. The research of Shi Ruokun (2011) on college teachers is a good proof. Through in-depth interviews, he found that most college teachers think that when the psychological contract is not fulfilled, objectively speaking, it will adversely affect the work, and the efficiency and effectiveness of the work will be reduced, but in general, it will not have great impact on their own work, especially the teaching work. College teachers have good professional ethics, which ensures that most people will perform their duties as teachers even if they are not satisfied with the psychological contract. It is not difficult to find that organizational commitment is similar to professional ethics, which makes it easy for us to understand its importance in the relationships between psychological contract, organizational support and employees’ work-related attitudes and behaviors.

5.4. Limitations and Prospects of This Study

First of all, this study conducts horizontal analysis only based on one aspect of organizational development. Longitudinal follow-up studies may be more appropriate, which is expected to be carried out by observing the effects of psychological contract breach of a group of samples on employees’ work attitudes and behaviors at different stages of the life curve of an organization according to time series. Secondly, due to the limit of manpower, material resources and financial resources, the number of respondents is not large, and most of them are employees. Since the subordinate relation is not embodied in the survey, there are still some deficiencies in sampling and analysis. At the same time, since the samples we selected include colleges and universities, institutions, and enterprises, the representativeness of the samples will be more ideal if the sample capacity is expanded or the samples are further subdivided. Thirdly, this study only explores the mechanism of the impact of psychological contract breach on employees’ work-related attitudes and behaviors in most cases. It’s also less convincing to explain this kind of relationship in special cases (such as financial crisis leading to enterprise dilemma and college students entering new workplaces). Therefore, future research should also consider introducing some new variables (such as regret) (Wang Liping, Yu Zhichuan, 2012) [30] .

6. Conclusions

1) Psychological contract breach directly affects job satisfaction, and has no direct impact on Organizational identification and various work-related behaviors; 2) Organizational commitment and organizational support all partially mediate the relationships between psychological contract breach and job satisfaction. At the same time, they all have mediating effect on the relationships between psychological contract breach and Organizational identification; 3) Psychological contract breach affects various work-related behaviors by affecting organizational commitment. Organizational commitment plays a mediating role; 4) Organizational support indirectly affects employees’ work-related attitudes and behaviors by affecting organization commitment, in which organizational commitment plays a mediating role.

Acknowledgements

The research is supported by the National Social Science Foundation of China (14BGL079).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Cite this paper

Yan, B.B., Huang, X.L. and Chen, X.Y. (2018) Does the Employee’s Work Attitude and Work Behavior Have the Same Stability? Open Journal of Social Sciences, 6, 176-191. https://doi.org/10.4236/jss.2018.610014

References

- 1. Morrison, E.W. and Robinson, S.L. (1997) When Employees Feel Betrayed: A Model of How Psychological Contract Violation Develops. Academy of Management Review, 22, 226-256. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1997.9707180265

- 2. Zhang, S.M. (2011) Psychological Contract Theory and Its Application in Administrative Organizations. Management World, 1, 180-181.

- 3. Zhao, X. and Ma, Q.H. (2015) Research on Customer Psychological Contract Violation Effect—An Empirical Analysis Based on the Impact of Customer Complaint Behavior. Technology Economics and Management Research, 8, 71-75.

- 4. Shi, J. and Cui, L.J. (2011) Foreign Psychological Contract Destruction and Outcome Variables and Regulatory Variables: Review and Prospects. Psychological Science, 2, 429-434.

- 5. Zhao, H., Wayne, S.J., Glibkowski, B.C., et al. (2007) The Impact of Psychological Contract Breach on Work-Related Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis. Personnel Psychology, 60, 647-680. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2007.00087.x

- 6. Chiu, S. and Peng, J. (2008) The Relationship between Psychological Contract Breach and Employee Deviance: The Moderating Role of Hostile Attributional Style. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 73, 426-433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2008.08.006

- 7. Fan, W., Ji, X.P. and Shao, F. (2011) An Empirical Study of the Impact of Employment Contract on Psychological Contract Destruction. Management Science, 6, 57-68.

- 8. Shen, Y.M. and Yuan, D.H. (2007) The Influence of Psychological Contract Destruction on Employees’ Work Attitude and Behavior. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 1, 155-162.

- 9. Restubog, S.L. and Bordia, P. (2009) The Interactive Effects of Procedural Justice and Equity Sensitivity in Predicting Responses to Psychological Contract Breach: an Interactionist Perspective. Journal of Business and Psychology, 24, 165-178. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-009-9097-1

- 10. Tekleab, A.G., Takeuchi, R. and Taylor, S. (2005) Extending the Chain of Relationships among Organizational Justice, Social Exchange, and Employee Reactions: The Role of Contract Violations. Academy of Management Journal, 48, 146-157. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2005.15993162

- 11. Zhao, L., Shen, Y.M., Wei, C.M., et al. (2011) The Influence of Psychological Contract Destruction on Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Regulating Role of Colleagues’ Supporting Feeling. Psychology, 6, 549-553.

- 12. Tian, H.F., Liu, Z.Z. and Wang, H.J. (2015) The Influence of the Psychological Contract of the New Generation Employees on the Organizational Behavior Relationship—An Empirical Study of the New Generation Employees in Xi’an after 90 Years. Journal of Xihua University (Philosophy and Social Sciences), 2, 85-90.

- 13. Aselage, J. and Eisenberger, R. (2003) Perceived Organizational Support and Psychological Contracts: A Theoretical Integration. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 24, 491-509. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.211

- 14. Hu, W.P. and Shi, K. (2004) Progress and Prospects of Organizational Commitment Research. Advances in Psychological Science, 1, 103-110.

- 15. Liu, X.P., Wang, C.M. and Brigitte, C.P. (2002) Simulation Experiment Research on the Influencing Factors of Organizational Commitment. Chinese Management Science, 6, 97-100.

- 16. Eisenberger, R., Huntington, R. and Hutchinson, S. (1986) Perceived Organizational Support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71, 500-507. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.71.3.500

- 17. Robinson, S.L. and Morrison, E.W. (2000) The Development of Psychological Contract Breach and Violation: A Longitudinal Study. Journal of Organization Behavior, 5, 525-546. https://doi.org/10.1002/1099-1379(200008)21:5<525::AID-JOB40>3.0.CO;2-T

- 18. Allen, N.J. and Meyer, J.P. (1990) The Measurement and Antecedents of Affective, Continuance and Normative Commitment to the Organization. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 1, 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.1990.tb00506.x

- 19. Hackman, J. and Oldham, G.R. (1974) The Job Diagnostic Survey: An Instrument for the Diagnosis of Jobs and the Evaluation of Job Redesign Projects. Affective Behavior, 4, 87.

- 20. Mael, F. and Ashforth, B.E. (1992) Alumni and Their Alma Matter: A Partial Test of the Reformulated Model of Organizational Identification. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 13, 103-123. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030130202

- 21. Farh, J., Chen, B.Z. and Dennis, O. (2002) An Inductive Analysis of the Construct Domain of Organizational Citizenship Behavior. The Management of Enterprises in the People’s Republic of China, 445-470.

- 22. Podsakoff, P.M., Mackenzie, S.B., Lee, J.Y., et al. (2003) Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 5, 879-903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- 23. Rosen, C.C., Chang, C.H., Johnson, R.E., et al. (2009) Perceptions of the Organizational Context and Psychological Contract Breach: Assessing Competing Perspectives. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 2, 202-217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2008.07.003

- 24. Lin, M. and Zhou, L. (2015) Labor Relations Climate, Perceived Psychological Contract Breach and Union Commitment: The Cross-Level Moderating Effect Democratic Grassroots Union Election. Chinese Journal of Management, 3, 364-371.

- 25. Qian, S., Xu, Z.Q. and Wang, L.Q. (2015) Research on the Relationship between the Psychological Contract Destruction and Turnover Tendency of the New Generation Employees. Modern Finance, 2, 102-113.

- 26. Suzanne, S.M., Lewis, K. and Taylor, M.S. (2004) Integrating Justice and Social Exchange: The Differing Effects of Fair Procedures and Treatment on Work Relationships. Academy of Management Journal, 4, 738-748.

- 27. Shi, R. (2011) On the Destruction of University Teachers’ Psychological Contracts by University Administration. Guangxi Social Sciences, 2, 157-160.

- 28. Carmeli, A. and Freund, A. (2004) Work Commitment, Job Satisfaction, and Job Performance: An Empirical Investigation. International Journal of Organization Theory and Behavior, 3, 289-390. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOTB-07-03-2004-B001

- 29. Coyle, S.J. and Kessler, L. (2000) Consequences of the Psychological Contract for the Employment Relationship: A Large-Scale Survey. Journal of Management Studies, 37, 903-930. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6486.00210

- 30. Wang, L.P. and Yu, Z.C. (2012) Research on the Influence of Psychological Contract Destruction on Organizational Citizenship Behavior: Based on the Mediating Role of Regret. Forecast, 3, 24-29.