Open Journal of Animal Sciences

Vol.04 No.05(2014), Article ID:50847,9 pages

10.4236/ojas.2014.45040

Do Policy Based Adoptions Increase the Care a Pet Receives? An Exploration of a Shift to Conversation Based Adoptions at One Shelter

Emily Weiss, Shannon Gramann, Emily D. Dolan, Jamie E. Scotto, Margaret R. Slater

Shelter Research and Development, Community Outreach, American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA®), New York, USA

Email: emily.weiss@aspca.org

Copyright © 2014 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 28 August 2014; revised 29 September 2014; accepted 20 October 2014

ABSTRACT

Animal shelters’ adoption processes vary across the US. Some programs have rigorous policy based programs in which potential adopters are screened in or out based on their responses to a series of qualifying questions. Some other organizations use a conversation based approach with- out policies around such things as income, vaccination status of animals in the home and landlord approval. Those organizations that use the policy-based approach do so with the premise that the animal will be loved and cared for better by those that meet their criteria. Policy based adoptions can be arduous and can decrease adoptions, as, for example, those living in apartments that are unable to prove their landlord accepts pets are turned away. We hypothesized that meeting or not meeting policy based criteria would have no impact on the care or bond of the adopter with the pet. This study examined the quality of care and attachment in two groups of adopters, a group that adopted while policy based adoptions were in place and a group that adopted when policies were eliminated. There were no substantial differences between the two groups. This important finding indicates that those that adopt through conversation based adoptions (policy-free) pro- vide similar high quality care and are just as likely to be highly bonded to their pet as those that adopt through policy based adoptions.

Keywords:

Animal Shelter, Human Animal Bond, Pet Adoption, Dog, Cat

1. Introduction

It is estimated that 7.6 million dogs and cats enter the sheltering system each year [1] . Finding adoptive homes for these animals is vital to preventing the euthanasia of millions of healthy dogs and cats; however, there is great debate among animal welfare professionals about appropriate methods of finding homes and preventing future relinquishment. Animal welfare professionals often express concern about the quality of potential adop- ters and debate adoption standards and requirements [2] . In an effort to ensure success of an adoption, many animal welfare groups have potential adopters undergo a standardized application process prior to taking a pet home. In the meantime, 2.7 million dogs and cats are euthanized each year [1] , while others endure long stays at the shelter awaiting adoption [3] . As only 20% - 30% of total owned pets are acquired through shelters and res- cues in the US [4] [5] , the market increase opportunities are substantial; however, when the opportunity presents itself for a dog or cat to be adopted, there are no guarantees that the adopter will meet the shelter’s set criteria.

Adoption screening processes vary from one agency to another but often include a rigorous application pro- cess for interested adopters filled with yes/no questions about such things as veterinary care for pets in the home, hours the applicant is away from the home, etc. Many also require proof of certain items such as providing per- sonal references, providing proof of veterinary visits for current or previous pets, consulting with landlords or requiring lease documents to verify that pets are allowed in the home, and/or requiring that all family members, including current pets, meet the dog or cat that they would like to add to the family. In addition, most agencies perform a formal interview as part of the adoption process.

Taylor [6] interviewed managers of animal welfare organizations in the UK and discovered that approximate- ly 50% of people coming to their facilities seeking to adopt an animal were denied based on their answers to preliminary questions in a phone interview. The shelter labeled these adopters as “bad homes” and the applicants were restricted from adopting from that agency. Strict policy-based adoption standards, similar to the standards in the UK, and the lack of truly successful adoption programs likely are significant contributors to adoptable dogs and cats not finding homes in shelters across the US.

Differences in adoption policies have historically been an area of significant debate among agencies re-hom- ing animals. Some perpetuate the belief that increasing the quantity of adoptions is done so at the expense of finding “quality” homes for dogs and cats and even vilify organizations that do not adhere to a rigorous screen- ing process prior to completing an adoption [3] . Research regarding pet relinquishment and returns to shelters have also come to varying conclusions. In 1999, Scarlett et al. [7] performed a study of pet relinquishment which led them to conclude that careful and sensitive questioning prior to adoption would help to prevent relin- quishment. While in 2005, Shore’s [8] inquiry of animals returned to a shelter found that “the majority of prob- lems that resulted in these failed adoptions were not ones that increased forethought or additional time spent in the shelter could have prevented”.

Challenging convention around policy-based adoptions, Weiss and Gramann [9] explored the difference in the bond between adopters who paid an adoption fee for their cat vs. those who had the adoption fee waived. They found that not only was there not a significant difference in the bond between the two groups, but also that more cats were adopted during fee waived promotions, return rates were unchanged and the length of stay for adult cats decreased during the fee waived promotions.

Many shelters around the country will not allow an adopter to adopt a pet as a gift for someone else such as a family member or loved one. This is despite several studies in the late 1990s and 2000 noting that pets obtained as gifts appeared less at risk for relinquishment [7] [10] -[12] . In a more recent study using a survey process it was found that receiving a dog or cat as a gift was neither significantly associated with impact on self-reported love/attachment, nor was it associated with whether or not respondents still had the dog or cat in the home [13] .

It may be hypothesized that animal welfare organizations performing rigorous adoption application proce- dures may be turning down suitable homes and, in spite of their efforts at protecting animals, are contributing to the pet surplus in US shelters. This study sought to address these issues by determining if there is any change in attachment or care when performing a restrictive policy-based adoption process versus forgoing that process for an informative conversation with potential dog and cat adopters. We anticipated not finding a relevant difference between these two groups.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The Toledo Area Humane Society (TAHS) is a 501(c)3 agency located in Maumee, OH, a suburb of Toledo. Annually, the agency cares for over 4000 animals [14] . Historically, the agency had strict adoption policies and all potential adopters filled out an application prior to being considered for adoption of an animal from the shel- ter. Prior to launching this research project, TAHS transitioned to decreasing some policies around their adop- tion process. However, they still strictly required landlord checks for adopters who rented their homes and dog introductions for adopters looking to adopt a dog and already had a resident dog. Baseline data collection was conducted while these policies were tightly in place and experimental data collection occurred after these poli- cies were eliminated. After completion of baseline data collection, the staff at TAHS received training to assist them in eliminating the rest of their policies prior to the start of experimental data collection.

Two groups of adopters at the Toledo Area Humane Society participated in this study—those who adopted an animal from the shelter with policies in place (required dog introductions with resident dogs and landlord checks to confirm that pets were allowed) from July 16-August 27, 2013 (policy group) and those who adopted with a policy free process from November 12-December 10, 2013 (policy-free group). At the time of adoption, indi- viduals in both groups signed a consent form allowing the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA) to follow-up with a phone or on-line survey at 30 days post-adoption. For the policy and policy-free groups, 156 and 120 consent forms were signed, respectively. The policy group was larger due to the season of data collection. Given the summer months, the shelter was inundated with kittens and, therefore, the large majority of consent forms were for kitten adopters. To have a balanced sample, collection of kitten adop- tion consent forms was halted while collection was extended for all other ages of canine and feline adoptions. This issue did not arise during policy-free group data collection as ‘kitten season’ had come to an end.

2.2. Methodology

For both the policy and policy-free data collection periods, any person who came to the shelter interested in adopting a dog or cat was directed to the adoption floor to look at available animals. When adopters expressed interest in a particular animal, they were sent to a private room to fill out a survey to learn about the adopter’s lifestyle and expectations (The ASPCA’s Meet Your Match (MYM) Canine-ality and Feline-ality surveys were used), and upon completion of the MYM survey, the adopters were given time to spend with the animal in the room. The MYM survey results were tools used as a guide for a conversation with an adopter to make a good match or explain how the selected pet might not be a good fit for the adopter’s lifestyle.

Once adopters made the choice to adopt a new pet, those in the policy group were required to provide land- lord information if they were renters and the TAHS staff contacted the landlord to ensure that pets were allowed on the residential property—if they weren’t allowed, adoption was denied. If the landlord could not be imme- diately reached, adopters were made to wait until the landlord could be reached. Additionally, if the adopter was choosing to adopt a dog and already had resident dog(s), an introduction at the shelter was required and, de- pending on how the staff perceived the dogs to get along, the TAHS staff made the decision whether to place the dog in the home. When adoption was approved, adopters were given a consent form to allow the ASPCA to fol- low-up with a survey at 30 days post-adoption. When adopters in the policy-free group made the decision to adopt (and no issues were identified that posed serious risk to the animal in the home according to the Adoptions Forum II guidelines, including the following: adopter had no known history of abuse towards animals or child- ren, adopter was not intoxicated at the time of adoption, and the animal would not be used as a food source), no further questions were asked beyond items up for discussion from the MYM survey, and the consent form was signed allowing the ASPCA to follow-up at 30 days post adoption.

2.3. Transition Rate Survey

To obtain information about the number of people coming to the shelter looking to adopt and, of those, the number who actually became adopters that day, a transition rate study was conducted with the goal to compare the transition rate of the policy and policy-free groups. To achieve this, one or two surveyors waited at the front door of the shelter during operating hours during both the policy and policy-free data collection periods. Indi- viduals or groups who came to the shelter during those hours were asked a number of questions pertaining to the reason for their visit. Those who indicated visiting the shelter with the intent to adopt or to look at animals were asked to specify the age and species of animals of interest (dog, puppy, cat, and kitten). After the shelter closed for the day and no further adoptions could be completed, the total numbers of dog, puppy, cat, and kitten adop- tions were tallied and a rate was calculated for the total number of potential adopters who became adopters as well as that rate broken down by species and age of interest.

2.3. Follow-Up Survey

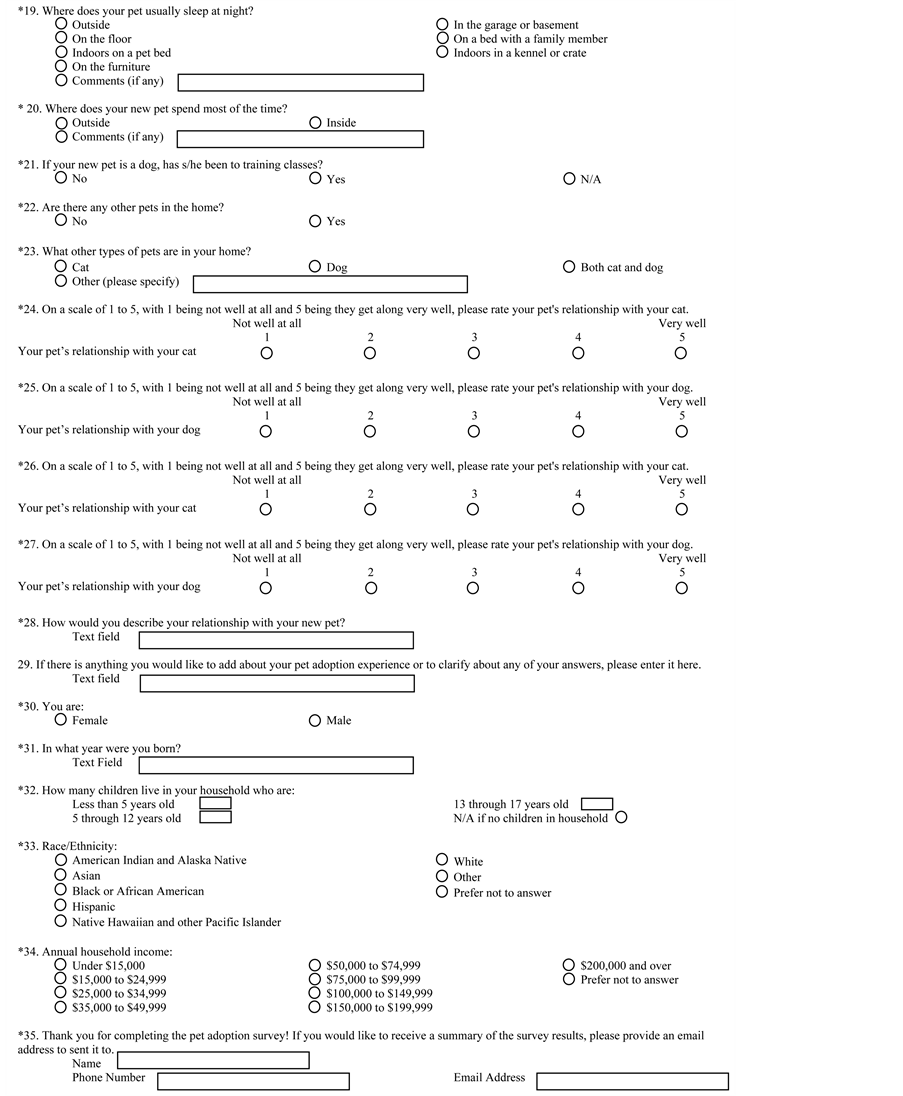

As we were specifically examining the care and attachment of the 2 groups of adopters with their pets, we con- ducted a survey with adopters 30 days post adoption The ASPCA Call Center contacted adopters of both groups via phone to complete the survey. Up to three attempts were made. When phone contact wasn’t successful, the survey link was provided in an email sent to the adopter using Survey Monkey. Survey questions, seen in Fig- ure 1, focused on basic demographic information about the adopters, the health, behavior, and medical care of the animal provided by the adopters, pet retention, where in the home the pet spends most of his/her time, adopter’s

Figure 1. Post adoption survey questions.

attachment to pet, overall experience at the shelter, and how the adopter perceived the shelter’s concern for new pet happiness post-adoption. These questions were identified as they gave insight to both the pet’s experience and care in the home, as well as the adopter’s perception of the pet.

2.4. Statistical Analyses

All statistical comparisons were conducted using Stata/IC 13.0 (StataCorp., College Station, TX, USA). We calculated frequencies for all variables. We used Pearson’s chi square to compare the two groups (policy vs. open) on: whether the respondents had ever adopted a pet from a shelter before, whether the pet wears an ID tag, been to the veterinarian since the adoption, ever goes outside, and received medication to prevent fleas ticks and heartworm. For the variable indicating where the pet sleeps at night, each category was compared to not sleeping in that location (e.g., sleeps in pet bed vs. doesn’t sleep in pet bed) because the respondents could give more than one answer. When the expected value of the cells was less than five, we used Fisher’s exact test to compare the two groups. This occurred for race, income, rating of overall experience at the shelter, the shelter’s concern for new pet happiness after adoption, attachment, whether the pet had or developed health or behavior problems, whether the cats were declawed and whether the dogs had been to training classes. Transition rate calculations were conducted using Microsoft Excel 2007 to divide the number of adoptions of the specific category by the number of individuals who entered the shelter intending to look at or adopt animals of that specific category.

3. Results

3.1. Survey Responses

We received completed surveys for 149 pets. We found a total of 6 pets reportedly no longer in the home. In the policy group, 2 had been returned to the shelter, one had been placed in a new home and one had passed away or been euthanized. In the policy-free group, one had been returned to the shelter, and one was in a new home. We found no significant difference between the two groups, p = 1.0. One person was missing this information and was not included in subsequent analyses. All analyses were conducted on surveys from the 96% of respondents who reported that their pet still lives with them, resulting in a sample size of 142 pets: 24 cats and 33 dogs in the policy-free group (48% of consenting adopters) and 31 cats and 54 dogs in the policy group (54% of consenting adopters). We found no significant association between group assignment to the policy-free or policy groups and the number of cats and dogs in each group p = 0.50. We found no significant association between group assign- ment to the policy-free or policy groups and the sex of the responder, p = 0.67, race (86% white), p = 0.28, and income, p = 0.95.

The raw frequencies for each variable and response category, stratified by group assignment, are in Table 1. We found that when asked to rate their experience at the Toledo Area Humane Society shelter, the majority of respondents in both groups reported excellent or very good (86%). We found no significant association between group assignment to the policy-free or policy groups and the rating of their experience at the Toledo Area Hu- mane Society shelter, p = 0.94.

We found that the majority of respondents in both groups agreed when asked to rate how concerned the shel- ter was with their new pets’ happiness after adoption (85%). All respondents reported at least moderate attach- ment to their new pet, with 98% reporting strong to very strong attachment. Respondents mostly reported no health or behavior problems at the time of adoption or new health problems in the first month after adoption. Very few respondents reported behavior problems at either time point. We found no significant associations be- tween group assignment to the policy-free or policy groups and: how concerned the respondents felt the shelter was with their new pets’ happiness after adoption, p = 0.35; whether the respondents had ever adopted a pet from a shelter before, p = 0.36, attachment to the new pet, p = 0.57, whether the pet had or developed health or behavior problems, p = 0.54, wearing an ID tag, p = 0.11, whether the pet had been to the vet since adoption, p = 0.36, if the pet was a cat, whether it was declawed, p = 0.49, whether the pet ever goes outside, p = 0.41, whether dogs had been to training classes, p = 1.0, the rating, on a scale from 1 to 5, with how well the new pet got along with a previously owned dog, p = 0.58 (amongst adopters who had a dog already living in the home), and whether the adopters reported the pet sleeps at night (no respondents reported the pet sleeping outside at night).

We did find a significant association between group assignment and whether the pet received medication to prevent fleas and ticks, p < 0.05. More than two-thirds of pets who received medication occurred in the policy group. We found a similar pattern for heartworm medication, though the statistical test revealed only a trend to- ward significance p = 0.09.

3.2. Transition Rate Data

The total transition rate for the policy-free group was 12% and for the policy group it was 11%.

Table 1. Frequencies (percent) of respondents in the policy-free group, for all variables including dogs and cats unless noted.

aRespondents could choose more than one location; na = not applicable.

4. Discussion

Often studies focus on differences between populations. In this case, the focus of the work was to examine the likely lack of differences between two populations in order to increase opportunities for dogs and cats to be adopted. Policy based adoptions are put in place in the belief that it will help assure a pet receives a high level of care in the home. This study found that moving from policy based adoptions to conversation based or policy- free (open) adoptions did not impact the risk for improper animal care. The adopted animals had no substantial differences in attachment, where they slept, vet visits and several other key factors. Policy based adoptions usually do not allow for the nuanced dialogue that can happen through a more conversational approach. A yes or no answer to a question loses the opportunity to learn why X or Y may not be in place. The move away from policy was not increasing the likelihood of adoption to an individual who intended to harm animal, but instead provided an opportunity for both client and counselor to have a more relevant and concrete conversation around their lifestyle and the pet they were interested in adopting.

Another limitation of some adoption policies is the amount of staff time (and sometimes adopter time) re- quired to enforce them. One of the most time consuming policies is requiring adopters who have a dog at home to bring that dog into the shelter to conduct an introduction to assure compatibility with the newly adopted dog. There is no data to support that conducting a dog to dog introduction in a shelter environment between the resi- dent and potential new dog prevents problems after adoption. Furthermore, the process most often involves re- quiring the potential adopter to come back to the shelter with their dog from home. Even if the shelter dog is ul- timately adopted, that dog ended up being kept in the shelter for longer than necessary, occupying kennel space that could have gone to a new shelter dog. This study found that adopters who were not required to do a dog to dog introduction were no more or less likely to have issues with the resident dog in the home than when an in- troduction was required. In fact, almost all adopters with resident dogs reported that their dog got along well with the new dog. An impressive 96% of the adopted animals were still in the home at the time of follow up. In addition, there were no differences in pet retention between the groups. These two points support the hypothesis that shelters using policy based adoption approaches could be wasting effort.

A recent report noted a positive relationship between veterinarian visits and retention [15] . That data suggests that it is likely that those who visit the veterinarian are those that are more bonded to their pets. In this study there was no significant difference in the likelihood that the pet visited the veterinarian with the vast majority (87.3%) having a veterinary visit prior to the 30 day follow up survey.

The differences the use of flea control and heart worm medication is likely explained by the timing for sur- veys for each of the two groups. As the research focused on an A-B design where we first collected data at the shelter while they still had fairly strict policy based adoption criteria and then worked to move the shelter staff from policy based to policy-free adoptions, time was needed to make that transition. While the policy group re- ceived their follow up survey in early fall while parasite risk was still high in Northern Ohio, the policy-free group was contacted for follow up in the middle of the Northern Ohio winter when fleas and mosquitoes are much less of a risk.

We were not expecting to find large differences between groups on key variables, as we hypothesized there would not be a difference in attachment or care between the two groups. We recognize that this study was only completed in one shelter with a modest sample size due to time and financial constraints. However, the beliefs about policy are pervasive and can have a sizable impact on live release and length of stay in the shelter making the need for data crucial. The modest differences we found between the policy and policy-free groups were small and consistent enough that we are comfortable in refuting the need for policy based adoptions. Therefore, we believe that this study provides useful conclusions to support the use of policy-free adoptions in the shelter setting.

We had hypothesized that there would be an increase in the transition rate between the two groups but there was no significant difference between the two groups. This may be a factor of the population in the shelter at the times of the policy vs. the policy-free group, and may also be a factor that the shelter’s policies were well known within the community, biasing the population choosing to enter toward those that were likely to both be tolerant of the policy based criteria and meet that criteria.

5. Conclusion

Policy based adoptions can be arduous and can decrease adoptions as many people simply do not meet the adop- tion criteria. These policy-based adoption programs are often used in shelters as a way to attempt to secure the best home for the pet, with the assumption that one that meets the adoption policy criteria will be more likely to care for and be attached to the pet. Our findings indicate that those that adopt through conversation based adop- tions (policy-free) provide similar high quality care and are just as likely to be highly bonded to their pet as those that adopt through policy based adoptions. As policy-based adoptions can restrict the pool of potential adopters, can slow down the adoption process, and change the experience for the potential adopter, a move to conversation based adoptions may be advisable.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Toledo Area Humane Society for their hard work in making the shift from policy based adoptions to conversation based adoptions and assisting with data collection for this project. We also thank Aditi Terpstra for her work on this project.

References

- ASPCA (2014) Pet Statistics. http://www.aspca.org/about-us/faq/pet-statistics

- Shore, E.R., Douglas, D.K. and Riley, M.L. (2005) What’s in It for the Companion Animal? Pet Attachment and Col- lege Students’ Behavior towards Pets. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science, 8, 1-11. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15327604jaws0801_1

- Miller-Dowling, J. and Stitely, C. (1997) Killing Ourselves over the Euthanasia Debate. Shelter Sense, 2, 4-15.

- American Humane Association (2013) Keeping Pets (Dogs and Cats) in Homes: A Three-Phase Retention Study. Phase 1: Reasons for Not Owning a Dog or Cat. http://www.americanhumane.org/aha-petsmart-retention-study-phase-1.pdf

- American Pet Products Association (2013) APPA National Pet Owners Survey, 2013-2014. American Pet Products Association, Inc., Greenwich.

- Taylor, N. (2004) In It for the Non-Human Animals: Animal Welfare, Moral Certainty, and Disagreements. Society and Animals, 12, 317-339. http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1568530043068047

- Scarlett, J.M., Salman, M.D., New Jr., J.G. and Kass, P.H. (1999) Reasons for Relinquishment of Companion Animals in US Animal Shelters: Selected Health and Personal Issues. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science, 2, 41-57. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15327604jaws0201_4

- Shore, E.R. (2005) Returning a Recently Adopted Companion Animal: Adopters’ Reasons for and Reactions to the Failed Adoption Experience. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science, 8, 187-198. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15327604jaws0803_3

- Weiss, E. and Gramann, S. (2009) A Comparison of Attachment Levels of Adopters of Cats: Fee-Based Adoptions versus Free Adoptions. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science, 12, 360-370. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10888700903163674

- New Jr., J.C., Salman, M.D., King, M., Scarlett, J., Kass, P. and Hutchinson, J. (2000) Characteristics of Shelter-Relin- quished Animals and Their Owners Compared with Animals and Their Owners in US Pet-Owning Households. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science, 3, 179-201. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/S15327604JAWS0303_1

- Patronek, G.J., Glickman, L.T., Beck, A.M., McCabe, G.P. and Ecker, C. (1996) Risk Factors for Relinquishment of Dogs to an Animal Shelter. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 209, 572-581.

- Patronek, G.J., Glickman, L.T., Beck, A.M., McCabe, G.P. and Ecker, C. (1996) Risk Factors for Relinquishment of Cats to an Animal Shelter. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 209, 582-588.

- Weiss, E., Dolan, E.D., Garrison, L., Hong, J. and Slater, M. (2013) Should Dogs and Cats Be Given as Gifts? Animals, 3, 995-1001. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/ani3040995

- Toledo Area Humane Society (2011) About Us. https://www.toledohumane.org/about/7-about-us

- American Humane Association (2013) Keeping Pets (Dogs and Cats) in Homes: A Three-Phase Retention Study. Phase 2: Descriptive Study of Post-Adoption Retention in Six Shelters in Three US Cities. http://www.americanhumane.org/petsmart-keeping-pets-phase-ii.pdf