Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

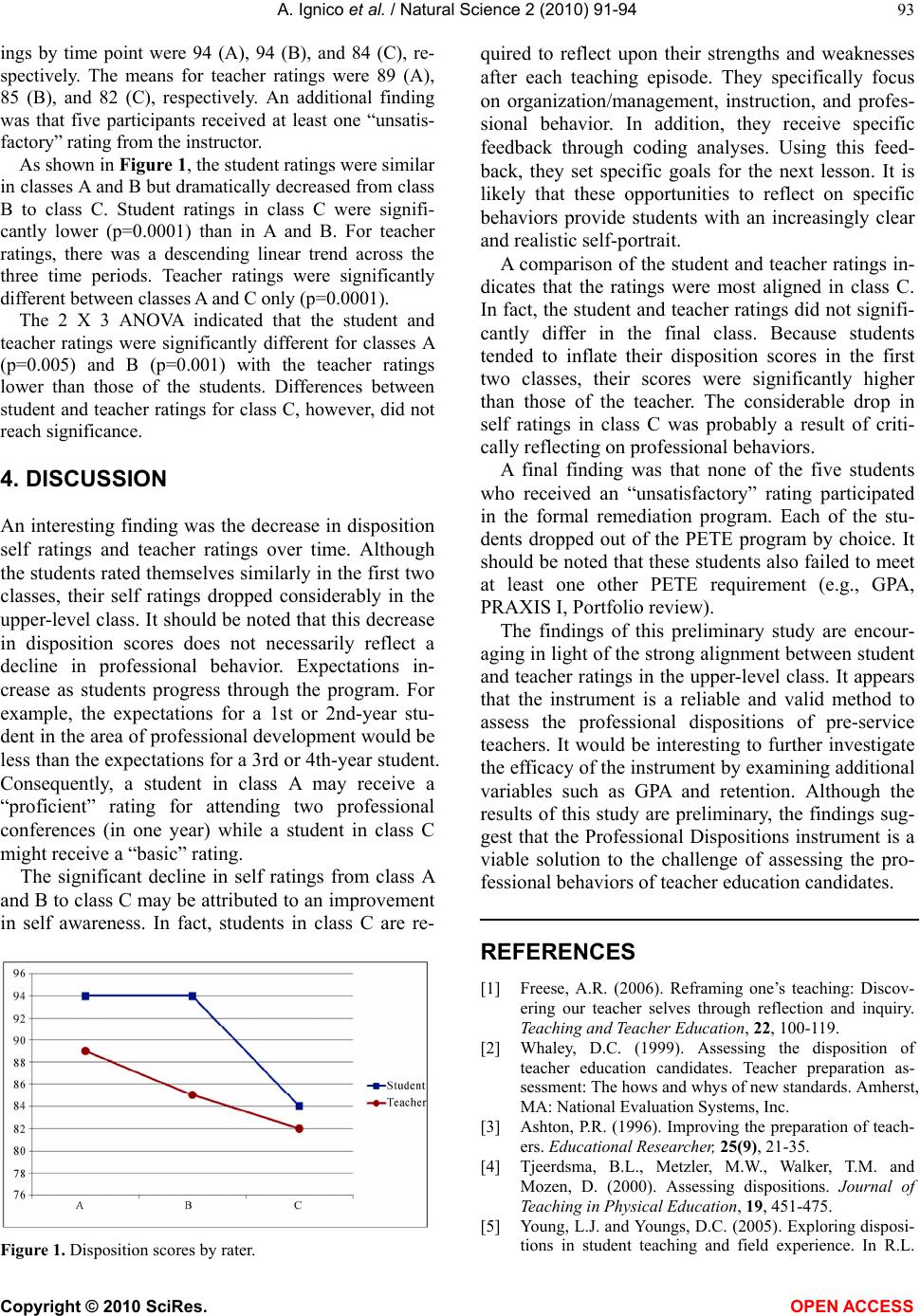

Vol.2, No.2, 91-94 (2010) Natural Science http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ns.2010.22014 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS A longitudinal study of the professional dispositions of teacher candidates Arlene Ignico, Kelly Gammon Ball State University, SPESES HP-221, America; aignico@bsu.edu Received 6 November 2009, revised 19. November 2009, accepted 15. December 2009. ABSTRACT The purpose of this study was to examine the professional disposition scores of Physical Education teacher candidates over time. In ad- dition, differences between teacher and student ratings were investigated. Participants were 65 students who completed three methods courses (A, B, and C) across a two-year period. Both the teacher and the students completed a profes- sional dispositions instrument in each of the three classes. Results indicated a decrease in disposition self ratings and teacher ratings over time. A 2 (Rater) x 3 (Time) ANOVA revealed that the student and teacher ratings were different for classes A and B but not for class C. The findings are encouraging in light of the strong alignment between teacher and student ratings in the upper-level class. The dispositions in- strument appears to be a valid and reliable method to assess the professional behaviors of teacher candidates. Keywords: Dispositions; Teacher Education; Professional Behavior 1. INTRODUCTION Both the National Council for the Accreditation of Teacher Education (NCATE) and the Interstate New Teacher Assessment and Support Consortium (INTASC) now mandate the assessment of dispositions in teacher education programs. Specifically, the NCATE 2000 Standards require schools, colleges and departments of education to use performance-based evidence to demon- strate that teacher candidates in all programs are gaining the knowledge, skills and dispositions necessary to have a positive impact on K-12 student learning. Similarly, the INTASC standards emphasize knowledge, skills, and dispositions that highlight the importance of perform- ance-based assessments. More recently, the National Initial Physical Education Teacher Education Standards (2008) added a standard requiring the assessment of professional dispositions. Standard number 6 states that teacher candidates must demonstrate dispositions that are essential to becoming effective professionals. Ac- cordingly, accredited teacher education programs through- out the nation have incorporated professional disposi- tions, in addition to the preexisting knowledge and skill performance requirements for prospective teacher can- didates. The assessment of professional behaviors has created considerable discussion and controversy among teacher education programs and teaching professionals. Most teaching professionals acknowledge the difficult chal- lenges in attempting to quantify personality characteris- tics and qualities [1,2]. Of great concern and scrutiny are the specifics of “how,” “who,” and “when” of disposi- tions. For instance, issues relating to the origins of dis- positions, the appropriate context for assessment, and the purposes they serve are all under question and examina- tion. One of these challenges is the considerable vari- ability in the methods used to assess dispositions. Be- havioral checklists, observations, reflections, journals/ logs, video analyses, portfolios, and rating scale rubrics are all examples of how dispositions are assessed. Ide- ally, instruments should offer the student the opportunity to reflect upon strengths, weaknesses, and teaching phi- losophy, as well as provide professional faculty the oc- casion to provide constructive feedback to the student [2]. Equally important is the opportunity for teacher candidates to develop a clear understanding of self and students [3]. Although the “who” of disposition assessment may seem obvious (teacher education majors), an important point of concern is the equally important variable of “who” conducts the assessment. Feedback is typically gathered from a combination of the following sources: the teacher candidates; instructors, program coordinators, field placement supervisors, and mentor teachers [1,2,4]. Even though gathering information from a pool of teachers seems beneficial, this raises concern as to how to best balance evaluation procedures among students and teachers. Relying on a combination of student  A. Ignico et al. / Natural Science 2 (2010) 91-94 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS 92 self-report measures and professional faculty assess- ments seems to provide the most reliable appraisal. An additional issue relating to dispositional assess- ment is “when” it should occur. The timeline varies from state to state and from institution to institution. In most cases, disposition assessment occurs at several stages in a variety of settings throughout the teacher preparation curriculum [1,4,5]. In some cases though, dispositions may only be addressed in the event of concerns being expressed about a teacher candidate as more of a reme- diation measure [2]. Most researchers agree that the as- sessment of professional dispositions must occur early and often in the professional preparation program. There are those who are critical of efforts to gauge the dispositions of pre-service teachers and of attempts to influence the development of dispositions as part of teacher education training [6]. It is clear, however, that assessing teacher dispositions has taken a foothold in teacher education programs and will only continue to be more fully integrated into the undergraduate curriculum. In comparison to skill performance and knowledge as- sessment instruments, there are only a few instruments to assess professional dispositions. Perhaps more impor- tantly, few studies have investigated changes in the pro- fessional dispositions of teacher candidates over time. In other words, what impact does the teacher education program have on a teacher candidate’s professional be- havior? The purpose of this study was to examine the profes- sional disposition scores of Physical Education Teacher Education (PETE) students over time. In addition, dif- ferences between student and teacher ratings were inves- tigated. 2. METHOD 2.1. Participants The participants for this longitudinal study were 65 PETE major students who completed three methods courses representing a 3-semester sequence. The same university instructor taught each of the three classes. 2.2. Instrument A Professional Dispositions Assessment that was devel- oped and tested at a large Midwestern university was used for this study. This assessment contains the follow- ing 10 items identified by the PETE faculty as represen- tative of professional behavior: 1) Attendance 2) In class performance 3) Class preparation 4) Relationship with others 5) Group work 6) Professional development 7) Respect for school rules, policies, norms 8) Emotional control/responsibility 9) Role model 10) Communication For each item, there are four possible ratings repre- senting unsatisfactory, basic, proficient, and distin- guished behavior (see [7] for a more detailed explanation of the instrument). 2.3. Procedure Professional dispositions are assessed by the instructor in seven PETE classes during the 4-year program. In most classes, students are required to complete a self assessment of their professional dispositions. One of the PETE requirements is to achieve a basic or higher rating for all ten items in each of the seven classes. If a student receives an unsatisfactory rating, she/he must complete a formal remediation process prior to enrolling in another PETE class. The three classes examined in this study represent 2nd and 3rd-year courses in the major. Prior to enrolling in the first of these three classes, students receive a thor- ough explanation about the dispositions instrument in two first-year classes. In addition, they complete a self assessment and receive an assessment from their teachers. The first class (A) is typically taken during the 3rd semester in the program. This class is an introduction to teaching physical education course and includes 12 hours of assisting/teaching in local schools. The second class (B) is a motor development class and includes 10 hours of teaching preschool students. The third class (C) is an Elementary School Methods class and includes a 15-hour practicum in a local school. Due to pre-requi- sites, the 3 courses are taken sequentially over a 3-se- mester period. In each of the three classes, the participants were evaluated by the instructor during the final week of the semester. In addition, they completed and submitted a self assessment during this same week. Although the instructor included the dispositions evaluation as part of the course grade, the relative point values differed across the three classes. For the purpose of comparison, the disposition ratings for each of the three classes were converted to percentage scores. 2.4. Data Analyses A 2 (Rater) X 3 (Time) ANOVA was used to analyze the disposition data. To keep the risk of a Type I error low, the alpha level was established at p<0.01 so that only results with probabilities of sampling errors of less than 1 in 100 would be declared statistically significant. 3. RESULTS Descriptive statistics showed the means for student rat-  A. Ignico et al. / Natural Science 2 (2010) 91-94 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS 93 ings by time point were 94 (A), 94 (B), and 84 (C), re- spectively. The means for teacher ratings were 89 (A), 85 (B), and 82 (C), respectively. An additional finding was that five participants received at least one “unsatis- factory” rating from the instructor. As shown in Figure 1, the student ratings were similar in classes A and B but dramatically decreased from class B to class C. Student ratings in class C were signifi- cantly lower (p=0.0001) than in A and B. For teacher ratings, there was a descending linear trend across the three time periods. Teacher ratings were significantly different between classes A and C only (p=0.0001). The 2 X 3 ANOVA indicated that the student and teacher ratings were significantly different for classes A (p=0.005) and B (p=0.001) with the teacher ratings lower than those of the students. Differences between student and teacher ratings for class C, however, did not reach significance. 4. DISCUSSION An interesting finding was the decrease in disposition self ratings and teacher ratings over time. Although the students rated themselves similarly in the first two classes, their self ratings dropped considerably in the upper-level class. It should be noted that this decrease in disposition scores does not necessarily reflect a decline in professional behavior. Expectations in- crease as students progress through the program. For example, the expectations for a 1st or 2nd-year stu- dent in the area of professional development would be less than the expectations for a 3rd or 4th-year student. Consequently, a student in class A may receive a “proficient” rating for attending two professional conferences (in one year) while a student in class C might receive a “basic” rating. The significant decline in self ratings from class A and B to class C may be attributed to an improvement in self awareness. In fact, students in class C are re- Figure 1. Disposition scores by rater. quired to reflect upon their strengths and weaknesses after each teaching episode. They specifically focus on organization/management, instruction, and profes- sional behavior. In addition, they receive specific feedback through coding analyses. Using this feed- back, they set specific goals for the next lesson. It is likely that these opportunities to reflect on specific behaviors provide students with an increasingly clear and realistic self-portrait. A comparison of the student and teacher ratings in- dicates that the ratings were most aligned in class C. In fact, the student and teacher ratings did not signifi- cantly differ in the final class. Because students tended to inflate their disposition scores in the first two classes, their scores were significantly higher than those of the teacher. The considerable drop in self ratings in class C was probably a result of criti- cally reflecting on professional behaviors. A final finding was that none of the five students who received an “unsatisfactory” rating participated in the formal remediation program. Each of the stu- dents dropped out of the PETE program by choice. It should be noted that these students also failed to meet at least one other PETE requirement (e.g., GPA, PRAXIS I, Portfolio review). The findings of this preliminary study are encour- aging in light of the strong alignment between student and teacher ratings in the upper-level class. It appears that the instrument is a reliable and valid method to assess the professional dispositions of pre-service teachers. It would be interesting to further investigate the efficacy of the instrument by examining additional variables such as GPA and retention. Although the results of this study are preliminary, the findings sug- gest that the Professional Dispositions instrument is a viable solution to the challenge of assessing the pro- fessional behaviors of teacher education candidates. REFERENCES [1] Freese, A.R. (2006). Reframing one’s teaching: Discov- ering our teacher selves through reflection and inquiry. Teaching and Teacher Education, 22, 100-119. [2] Whaley, D.C. (1999). Assessing the disposition of teacher education candidates. Teacher preparation as- sessment: The hows and whys of new standards. Amherst, MA: National Evaluation Systems, Inc. [3] Ashton, P.R. (1996). Improving the preparation of teach- ers. Educational Researcher, 25(9), 21-35. [4] Tjeerdsma, B.L., Metzler, M.W., Walker, T.M. and Mozen, D. (2000). Assessing dispositions. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 19, 451-475. [5] Young, L.J. and Youngs, D.C. (2005). Exploring disposi- tions in student teaching and field experience. In R.L.  A. Ignico et al. / Natural Science 2 (2010) 91-94 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS 94 Smith, D. Skarbek & J. Hurst (Eds.), The passion of teaching: Dispositions in the schools (pp. 135-152). Lanham, MD: Scarecroweducation. [6] McKnight, D. (2004). An inquiry of NCATE’s move into virtue ethics by way of disposition (Is this what Aristotle meant?). Educational Studies Journal of the American Educational Studies Association, 35(3), 212-230. [7] Wayda, V. and Lund, J. (2005). Assessing dispositions: An unresolved challenge in teacher education. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 76(1), 34-41. [8] Mitchell, A. (2000). NCATE 2000: Teacher education and performance-based reform. Washington, D.C.: Na- tional Council for Accreditation of Teacher Education. |