Health

Vol.5 No.7(2013), Article ID:35112,8 pages DOI:10.4236/health.2013.57158

Beliefs and practices of young women on utilization of prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV services in Malawi

![]()

1Kamuzu College of Nursing, Lilongwe Campus, Lilongwe, Malawi; *Corresponding Author: rmuheriwa@kcn.unima.mw

2Kamuzu College of Nursing, Blantyre Campus, Blantyre, Malawi

Copyright © 2013 Sadandaula Rose Muheriwa et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received 18 April 2013; revised 19 May 2013; accepted 27 June 2013

Keywords: Prevention of Mother to Child Transmission of HIV; HIV Positive Young Women; Beliefs on PMTCT Services; PMTCT Practice; Exclusive Breast Feeding

ABSTRACT

This study explored beliefs and actual practices of young women on utilization of Prevention of Mother to Child Transmission (PMTCT) of HIV services in Balaka district of Southern Malawi. The study design was cross sectional which utilized qualitative data collection and analysis methods. In-depth interviews were conducted on 12 young mothers of 15 to 24 years old. The respondents were drawn from 6 health centres in the district during their visits to either the under-five clinic, HIV and AIDS support groups or HIV follow up clinics. Data were analyzed using thematic analysis approach. Overall the respondents had positive beliefs on utilization of PMTCT services. They believed that adherence to PMTCT guidelines such as condom use, taking of Nevirapine (NVP) and exclusive breastfeeding protected the baby from contracting the virus. Nevertheless, all respondents believed that HIV testing was mandatory and that early weaning caused malnutrition and death of babies. Actual practice was very low. Very few young mothers breastfed exclusively, weaned their babies abruptly and took NVP as recommended. Not all positive beliefs translated into positive behavior. Lack of male support, inability of the midwives to provide comprehensive care to HIV infected mothers and their infants, and fear of stigma and discrimination were other factors that hindered utilization of PMTCT services. Culture was also a major barrier because traditionally babies are expected to be breastfed and supplements are fed to babies too. There- fore, there is a need to mobilize communities on PMTCT of HIV. Education programmes in HIV should emphasize behavior change interventions and should focus on both men and women and significant others. There is also need to intensify monitoring and evaluation of health workers’ activities to ensure that beliefs translate into positive behavior.

1. INTRODUCTION

Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) infection is one of the major causes of child deaths in Malawi and worldwide [1,2]. According to United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), 13% of the under-five child deaths in the year 2010 in Malawi were due to HIV [3]. Evidence shows that 90% of these children acquired HIV through Mother to Child Transmission (MTCT) during pregnancy, labour and delivery or through breastfeeding. About 30,000 new infant infections occurred every year [4].

To prevent further spread of HIV from mother to child, the government of Malawi introduced Prevention of Mother to Child Transmission (PMTCT) of HIV services in 1999. It is well documented that proper use of PMTCT services reduces HIV infection in children by 40% to 70% [5]. The impact is closer to 70% when women do not breastfeed [5]. Prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV services therefore contributes to the attainment of Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) 4 and 6 of reducing child mortality and 6 HIV infection respectively.

The PMTCT guidelines in Malawi have changed since their introduction in 1999. Initially (during the time of this study), the PMTCT guidelines recommended the provision of Single Dose Nevirapine (SD NVP) to the mother at the onset of true labour when the mother’s CD4 count was greater than 350 cells/mm3. In addition the mothers were initiated on Antiretrovirals (ARVs) which was a combination of Lamuvidine, Stavudine and Nevirapine (NVP) when their CD4 count was low (below 350 cells/mm3). The guidelines also recommended the provision of SD NVP to the baby within 72 hours of delivery. The baby had to be exclusively breastfed for 6 months and then abruptly weaned to reduce mother to child transmission of HIV [6]. Recently, since July 2011 the Ministry of Health in Malawi introduced Option B+ of PMTCT in which all pregnant and lactating mothers are initiated on a combination of Tenofovir, Lamivudine and Efavirenz regardless of CD4 count and the newborn is initiated on Nevirapine continuously from birth to 6 weeks. In addition, the mothers can breastfeed up to 2 years [5]. The Option B+ has been proved to be better than the previous guidelines because in the United States of America the Option B+ has reduced MTCT of HIV from 26% to 1% [6].

Massive campaigns have been initiated by the Ministry of Health and other stakeholders to sensitize Malawians on the benefits of PMTCT. Pregnant women are being sensitized on PMTCT services during antenatal care clinics. Despite the massive campaigns, utilization of PMTCT services is very low [7]. By the end of 2007, only 26% of pregnant women with HIV in the country had utilized PMTCT services [8,9]. The purpose of this study was therefore to explore the beliefs and practices of young women on utilization of PMTCT services in Malawi. Studies indicate that beliefs on PMTCT services determine the utilization of the services by HIV positive pregnant women [10-12].

2. METHODS

2.1. Design

The study design was cross sectional and utilized qualitative methods of data collection and analysis to investigate beliefs and practices of young women (15 - 24 years old) regarding their utilization of PMTCT services. Data were collected using a semi structured interview guide. The tool solicited information on the young women’s beliefs and practices on HIV Counseling and Testing (HCT), condom use, taking of NVP and ARVs, infant feeding practices and their experiences with PMTCT services during pregnancy, labor and delivery and during the postnatal period.

2.2. Sample and Setting

Twelve (12) respondents participated in this study. Data saturation was reached after interviewing 10 respondents but 2 more young women were added to validate the results. Purposive sampling method was used to recruit individuals that had rich and first hand information on the utilization of PMTCT services. Specifically the young women had to be HIV positive, had attended antenatal clinic, and had a baby who was delivered within 18 months of the study.

The study was conducted in Balaka district which is located in the southern region of Malawi and has a population of 316,748 with 151,637 being males and 165,111 females. About 23% (72,852) are women of child bearing age [13]. The sample was drawn from six health facilities from February to March 2010. Two health facilities are located within Balaka township while the remaining four are located in the rural areas of the township. Balaka district was chosen because at the time of the study the district had a higher HIV prevalence rate (17.4%) than the average national prevalence (12%) [14]. In addition, the district’s prevalence of early childhood bearing among young women aged 15 - 19 years of 36.5% was higher than the national prevalence of 34.5% [13]. Furthermore, the district recorded high infant and under-five mortality rates that were estimated at 104 and 160 per 1000 live births respectively [13]. These figures were also higher than the national statistics for infant and under-five mortality rates which were 69 and 118 per 1000 live births respectively [13]. The respondents were recruited from under-five clinics, HIV and AIDS support groups, and HIV follow-up clinics.

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

To be included in the study, the women should have delivered within the past 18 months, be HIV positive, willing to participate in the study and able to communicate in either English or the vernacular language (Chichewa). Women whose babies were over 18 months old, or those aged below 15 years and above 24 years or could not communicate in either English or the vernacular language were excluded from the study.

2.4. Ethical Considerations and Procedures

Approval to conduct the study was first obtained from College of Medicine Research and Ethics Committee. Other approvals were obtained from the District Commissioner, the District Health Officer of Balaka district hospital, and the officers in charge of the health centers. Selection of the respondents and data collection were done by the researcher. Eligibility status for inclusion into the study was determined by asking the clients questions and checking the respondents’ health passport books for confirmation of HIV status and the ages of the mother and the baby. Eligible clients were informed about the details of the study in order to obtain their consent. They were told that participation into the study was voluntary and that they were free to withdraw their consent any time. The consenting respondents were then asked to sign a consent form to indicate their willingness to participate in the study. Upon signing the consent form, the questionnaire was orally administered to the consenting respondents where the researcher asked questions from the questionnaire and ticked the responses based on the respondents’ answers. The in depth interviews lasted 30 to 45 minutes. Anonymity and confidentiality of the respondents and their responses was maintained throughout the study by referring them with code numbers instead of their names.

2.5. Data Management and Analysis

Data were tape recorded, transcribed verbatim and translated into English. Field notes were taken to capture elements of the setting and of the respondents’ demeanor, emotional responses, and other contextual factors that could not have been captured on recording. An independent person listened to the recorded interview and verified the translation to ensure correctness. Data were analyzed using thematic analysis [15]. Data were coded manually line by line to come up with categories. From these categories, themes and sub themes were developed on beliefs and practices of young women’s utilization of PMTCT services. The themes and sub themes are reported as study results.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Demographic and Socioeconomic Characteristics

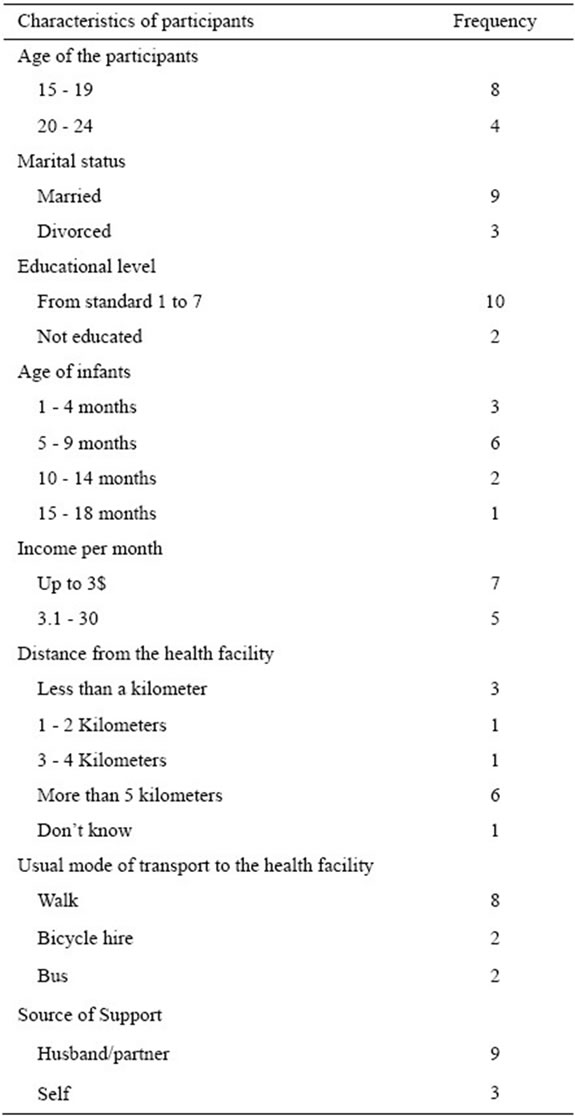

The demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of the respondents are shown in Table 1.

A total of 12 young postnatal HIV positive women participated in the study. Their ages ranged from 15 to 24 years. The respondents had infants whose ages ranged from 1 day old to 18 months. In this table, the majority of the respondents were married and their level of education ranged from standard 1 up to standard 7. Most of the respondents (6) lived over 5 kilometres (km) away from the nearest health facility. The commonest mode of transport was walking on foot for 8 of the respondents. Those that hired bicycles were 2 and the other 2 respondents went to the facilities by bus. The majority (7 out of 12) of the women earned up to $3 and 9 out of 12 respondents were supported by their husbands, while 3 respondents supported themselves.

Table 1. Characteristics of the participants (n = 12).

3.2. Beliefs about PMTCT Services

The qualitative narrations of the twelve (12) respondents regarding their beliefs gave rise to five themes which were; participation in HCT, condom use, taking SD-NVP or ARVs, infant feeding practices, and utilization of PMTCT services.

3.2.1. Beliefs Related to Participation in HIV Counseling and Testing

The majority of the respondents had positive beliefs and feelings towards HCT. They believed that HCT was helpful because it helped them to know their status and to protect their babies from contracting the HIV virus. Nevertheless, all the respondents believed that HCT was mandatory in the antenatal clinics. One respondent commented: “Nowadays there is no way you can run away from having your blood tested, whether you like it or not, they will test your blood otherwise you may not receive antenatal care.” Respondent #5.

It also emerged that some respondents (5 out of 12) were convinced on the necessity of HCT after being encouraged by their husbands who had positive beliefs about HCT as narrated by respondent #8. “Initially I did not believe in HCT and I had no wish to get tested but my husband was the one who persuaded me. So when I got tested it’s when I believed that HCT is helpful”.

The majority of the respondents (8 out of 12) indicated that their husbands had negative beliefs on HCT and utilization of PMTCT services. These women were barred by their husbands to utilize the services. The husbands did not only refuse their wives from getting tested but they also did not want to get tested. Three of the twelve respondents reported that their husbands divorced them after they disclosed to them their HIV positive status. Respondent #4 narrated as follows; “…when I told him that I tested positive, his reaction was ‘that is the end of our marriage’.”

3.2.2. Condom Use

All respondents believed that condom use was another way of preventing MTCT of HIV. However, none of them used condoms during pregnancy because their husbands disapproved condom use. One respondent described her situation as follows:

“I knew that condoms protect the baby from contracting the virus and I was willing to use them; but my husband refused the condoms, so we did not use them. Sometimes he threw them away”. Respondent #6.

Negative beliefs about condom use were based on myths. For example, the participants believed that the sperm is the real food for the growing fetus as shared by Respondent #10: “We believe that a seed grows with watering. So the husband’s sperm is the real food for the baby. For a normal baby development it needs the food that the husband gives a woman during plain sex”.

3.2.3. Taking Nevirapine

The majority of the respondents (10 out of 12) said that they had positive beliefs about NVP because it protects the baby from contracting the virus. However, the respondents had misconception regarding its side effects. The respondents believed that NVP causes abortion, makes women deliver a dead baby or causes the women body to become swollen after delivery.

3.2.4. Infant Feeding Practices

Majority of respondents believed that PMTCT can be achieved through proper infant feeding practices. For example they believed that when a child is exclusively breastfed and weaned at six months, the child does not contract the virus. This point was shared by Respondent #1 as follows:

“I believe that when you breastfeed the baby for six months without adding anything, the baby does not contract the virus. It’s true. I breastfed exclusively and when I took my child for a blood test, she tested negative”.

The issue of breastfeeding was very contentious and the respondents gave different explanations. For example, Participant #7 narrated that: “weaning a baby at an early stage is not good, it is ill treating the baby and the baby can become malnourished and die.” Other respondents believed early cessation of breastfeeding in the villages invited witches to bewitch the child as shared by Respondent #9: “…like in our society when one decides to wean her baby at such an early age, she should make sure that people should not know about it, otherwise you invite witchcraft because they take advantage of the situation and they bewitch the child and if the child dies they say it is because of the early cessation of breastfeeding”.

3.2.5. Utilization of PMTCT Services

A few respondents (3 out of 12) reported positive beliefs about utilization of PMTCT services. The beliefs expressed were related to the outcome of the baby and feeding practices. The respondents indicated that government introduced the PMTCT programme to assist women deliver healthy and HIV free babies. In case of an infection, both the mother and child are assisted to live longer lives than without PMTCT services.

The majority of the participants (9 out of 12) had negative beliefs about the utilization of PMTCT services because the utilization of the services was associated with stigma and discrimination. Some respondents indicated that some of the HIV positive women in the society were willing to follow the PMTCT guidelines but they were afraid that people in the society would discover that they were HIV positive and they would become a laughing stock. Respondent #12 narrated her experience of societal stigma and discrimination as follows:

“Even us, (meaning herself and other people who go to the PMTCT support group) people laugh at us and they discuss us. When we go to the funeral or to the borehole to draw water, or to any place where women gather, they point at us, whispering to each other that, we have AIDS… They do not say that we are HIV positive but they say we have AIDS and hence we will die soon.”

Religious beliefs were also reported by the respondents as hindering utilization of PMTCT services. Some respondents (6 of the 12) reported the belief that people who believe in God are not supposed to follow the PMTCT services. This point was shared by Respondent # 1 as follows:

“Many people are not following the programme because they say they are believers. They are saying that all those who believe in God are not supposed to join this programme. They are supposed to just believe in God and that everything will be well with them.”

3.3. Actual Practices of the Respondents in the Utilization of PMTCT Services

Analysis of the young women’s accounts revealed five distinct practices related to utilization of PMTCT services: HIV counseling and testing, giving of ARVs and NVP to infants, Exclusive breastfeeding up to 6 months and early cessation of breastfeeding and satisfaction with use of PMTCT services.

3.3.1. HIV Counseling and Testing

The in-depth interviews revealed that all the respondents in the study received HIV counseling and testing. They were all knowledgeable about the PMTCT programme and they all participated in the programme. However it also emerged that not all of them could have accepted the HIV counseling and testing if they were given an opportunity to chose whether to be tested or not. One respondent explained: “I was forced to have an HIV test. I didn’t want... given choice I could not have accepted”.

3.3.2. Giving of ARVs

The results revealed that some of the respondents got the ARVs or SD-NVP depending on the policy of the health facility. For instance, four (4) of the twelve (12) respondents who were interviewed from the private health facility (Dream health centre) were given ARVs regardless of the level of CD4 count while the rest of the respondents were given SD-NVP to take at the onset of labour and they were put on ARVs only when the CD4 count was less that 350/mm3.

Out of the twelve (12) respondents who delivered in the health facility, six (6) reported that their infants received NVP after delivery. For those whose babies did not receive the NVP the reasons given were that either the drug was out of stock or the midwife forgot to give the baby the NVP as reported by Respondent #12 “…no my child did not receive the drug because the midwife forgot… I knew because my friend whom we delivered together on the same day, her baby was given the drug.”

3.3.3. Exclusive Breastfeeding up to 6 Months and Early Cessation of Breastfeeding

Out of the nine (9) respondents who had children above 6 months, only one reported that she breastfed exclusively for 6 months. The rest of the respondents reported that they introduced supplementary foods earlier by the fifth month, with others introducing supplementary feeds as early as when the child was one month old. Those who were interviewed from the private health facility reported that they were given rice and were advised to introduce cooked rice water to the baby at five months, and were advised to wean their babies at nine months.

The majority of the respondents (11 of the 12 respondents) reported having problems with early cessation of breastfeeding because of stigma, discrimination, and poverty. The participants said they could not find enough and proper weaning foods for their babies. Respondent # 10 reported: “I am still breastfeeding my child up to this time (10 months), because I can’t afford proper weaning foods …but also I am afraid that people in my community may notice that I have AIDS”

3.3.4. Satisfaction with PMTCT Services

The in-depth interviews also revealed that five respondents had been in PMTCT programme with previous pregnancies. These respondents reported that they were diagnosed HIV positive during their previous pregnancies and this was their second time to be in the PMTCT programme. These respondents reported that their babies tested HIV negative after taking NVP at birth. The respondents were pleased with this development and they expressed the desire to have another pregnancy. Respondent #6 narrated: “I have been in the programme for quite some time and I don’t regret… my child was tested and is now HIV negative”.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Beliefs about HIV Counseling and Testing

The results on beliefs about HCT revealed that the majority of the respondents had positive beliefs. This probably explains why all respondents indicated that that they all got tested. However, interviews revealed that the respondents got tested because they were forced to have an HIV test. The respondents indicated the belief that HIV testing was mandatory as no one was given antennatal services without having an HIV test. This implies that women are not given chance to opt out. This demonstrates misunderstanding of opt out approach adopted by the government of Malawi by the PMTCT service providers. The opt out approach implies that screening should occur after a woman is notified that HIV screening is recommended for all pregnant women and that she will receive an HIV test as part of the routine panel of prenatal tests unless she declines [16]. These findings suggest an urgent need to evaluate policy and practice of antenatal care and opt-out approach in particular. Health workers should not lose sight of each woman’s right to make informed decisions about her health care, including her decision to learn her HIV status. Where women are forced to have an HIV test or are tested without their informed consent, their basic human rights are severely compromised. Compulsory HIV testing, the most obvious threat to the right to informed consent can constitute a deprivation of liberty and a violation of the right to security of person, recommended in the international guidelines on HIV/AIDS and Human Rights [17]. This calls for PMTCT providers to be trained on this new approach to effectively communicate the new routine HIV testing approach and dispel the misconception that HIV testing is mandatory.

4.2. Beliefs about Condom Use

The belief that sperm is real food for the growing baby and that using condoms would deprive the baby of its food implies that myths and misconceptions about condom use still exist regardless of the efforts made by government and nongovernmental organizations in dispelling these myths and misconceptions. The myths and misconceptions about condoms are not surprising. A study conducted in Mulanje district in Malawi and in Zambia among the youths revealed that very few clients agreed to use condoms claiming that, condoms cause cancer, are not nice, they lead to permanent infertility, and they reduce sexual satisfaction [18,19]. Misconceptions about condoms are common and can confuse people and thereby hinder HIV prevention efforts. These results suggest that preventive programs for this population possibly should focus on issues of sexuality, what makes one to enjoy sexual intercourse and on dispelling the misconceptions so that the young people have adequate and proper information about using condoms. This can help the young people develop positive beliefs that can promote utilization of condoms. Studies have demonstrated that the beliefs that individuals have on utilization of services motivate them to utilize those services [20,21].

4.3. Beliefs about Taking ARVs and Single Dose Nevirapine

The finding that majority of young women had positive beliefs and feelings about taking ARVs and SDNVP, is a welcome development because positive beliefs about ARVs and SD-NVP are associated with adherence to the medication [11,22]. A study in Tanzania revealed that most women came for antenatal care and utilized the PMTCT services because they believed and had confidence in the benefits of the services [23].

However, the belief that when one takes NVP, can abort, deliver a dead baby or become swollen after delivery, or that will not live longer implies that people tend to exaggerate the side effects of NVP. The implication of this is that these negative beliefs can hinder utilization of the PMTCT services. A study in Uganda found that the people who did not utilize the PMTCT services had negative beliefs about utilization of the PMTCT services [24]. It is therefore crucial that efforts be made to impart all HIV positive young women with adequate information about drugs used in PMTCT programme in order to enhance positive beliefs among the young women and promote compliance to medication used in PMTCT programme.

4.4. Beliefs about Infant Feeding and Early Cessation of Breastfeeding

The finding that majority of respondents had negative beliefs towards early cessation and the fact that the majority of young women did not wean their babies at six months implies that this guideline was not accepted by young women. This probably implies that the guideline was not suitable for Malawian women considering the poverty levels of the country as 85% of the population lives in the rural area with most of them unable to meet their daily consumption needs [4]. This therefore means that Option B+ has been introduced at a right time since in this approach women are allowed to breastfeed up to two years. It is therefore recommended that policy makers in Malawi should firstly conduct research to assess the suitability of new guidelines before implementation.

Stigma and discrimination were perceived by the majority of the respondents in this study. These results highlight that HIV and AIDS still remain highly stigmatized despite government’s efforts to reduce HIV-related stigma. Uptake and adherence to the PMTCT programme can be difficult for women whose society is stigmatizing and not supportive of their participation in the PMTCT programme. It is difficult for HIV-infected women to seek long-term treatment and care and to attend support programmes for both themselves and their infants without the community supporting them [25,26]. It is therefore crucial that the government find concrete measures that reduce stigma and discrimination. Efforts to minimize the stigma associated with HIV should be undertaken through education and empowerment of women as stigma and discrimination are often a result of lack of or incorrect knowledge.

It is clear that some religious beliefs, together with the belief that HIV is associated with witchcraft, are posing a greatest challenge to the PMTCT delivery system among the young women. These findings are similar to the findings of the studies done in Malawi and Kenya where some PMTCT service providers and community workers cited a wide spread belief in witchcraft and in faith healing as a challenge to utilization of PMTCT services [6, 27]. It is therefore essential that religious and community leaders be involved in PMTCT programmes.

The results also revealed that still a lot of men have negative beliefs and feelings about utilization of PMTCT services. This is evidenced in this study whereby 3 respondents reported that they were divorced after disclosing their positive HIV status. This is a concern considering the fact that the government of Malawi is currently advocating for more partner support of people who are HIV positive. These results are similar to the results of the study conducted in Chiradzulu district which revealed that all mothers (N = 9) in the study, had their families disrupted after they disclosed their HIV positive status. When some of them (44%) got remarried and disclosed their HIV status, the new partners also left [28]. This suggests the need for health workers and community leaders to strengthen policies and guidelines that promote male involvement in maternal and neonatal health issues [29].

However, the results further revealed that, not all positive beliefs translated into positive behavior. This result contradicts with results from Cameroon, Uganda and Bangladesh which indicated that positive beliefs on utilization of PMTCT services resulted in utilization of PMTCT services by HIV positive mothers [11,12,30]. However, the results revealed that apart from beliefs of an individual on PMTCT services, utilization of PMTCT services is also influenced by other factors such as, availability of resources, partner support, poverty and stigma and discrimination. Culture was also a major barrier because traditionally babies are expected to be breastfed and supplements are fed to babies too.

5. CONCLUSIONS

The results revealed that not all positive beliefs translated into positive behavior in young women in Balaka district. There is a need for comprehensive and sustainable HIV education with young people to ensure that positive beliefs translate into positive behavior. This is because the majority of HIV infections in Malawi occur amongst this age group. The HIV education programme should put emphasis on primary HIV prevention because these are the most effective ways to reduce the proportion of infants infected by HIV. The HIV education programmes should emphasize behavior change interventions and should focus on both men and women, their partners and significant others.

Stigmatization was one of the factors hindering utilization of PMTCT services, therefore, there is a need to raise awareness among the beneficiaries on stigma. The health workers in Balaka district should mobilize the communities to utilize the PMTCT services and should use social networks to encourage community support, education and action. Community mobilization should also include creating social or religious support groups where religious beliefs that negatively affect utilization of PMTCT services would be discussed and resolved. Monitoring and evaluation activities should be strengthened to ensure that midwives especially in the rural areas are delivering their duties according to the standard of practice stipulated by the Nurses and Midwives Council of Malawi. The District Health Management Team should also conduct regular in-service trainings to PMTCT providers and HIV counselors to encourage them to provide comprehensive messages about PMTCT services and to strengthen their skills on how they can influence behavior change in young women for them to comply with the PMTCT guidelines.

This study should be replicated to a larger scale to further explore the beliefs and practices of young women on utilization of PMTCT services in the entire nation including those women outside this age group. A study should also be carried out to identify the beliefs and practices of men on PMTCT services and the nature of support required by the young women to ensure utilization of PMTCT services.

6. LIMITATIONS

This study focused on young women aged 15 to 24 years, those who were in the postnatal period. These results do not reflect women outside this age group. Also the study focused on HIV positive women only and those already in PMTCT programme. These respondents would have already been motivated. These results do not reflect the beliefs and practices of those who have not been enrolled into the programme.

7. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I wish to express my most grateful thanks to Tsogolo La Thanzi project for the scholarship granted which helped me to pursue the Masters Programme and conduct this research.

![]()

![]()

REFERENCES

- Kafulafula, G. (2007) Post-weaning gastroenteritis and mortality in HIV-uninfected African infants receiving antiretroviral prophylaxis to prevent MTCT of HIV. The 14th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, 25-28 February 2007, Los Angeles.

- WHO (2010) HIV transmission through breastfeeding: A review of available evidence from 2001 to 2007. www.who.int/entity/nutrition/topics/Paper5InfantFeedingbangkok.pdf

- UNICEF (2013) Count down to zero: Elimination of new HIV infections among children by 2015 and keeping their mothers alive.

- UNICEF (2007) The situation of women and children.

- Ministry of Health (2011) Clinical management of HIV in children and adults: Malawi integrated guidelines in providing HIV services in: Antenatal care, maternity care, under five clinics, family planning clinics, exposed infant? Pre-ART clinics, ART clinics. Design Printers, Lilongwe.

- Ministry of Health (2006) National prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) training package: Participant manual. Design printers, Lilongwe.

- Car, L.T., van-Velthoven, M.H., Paljarvi, T., Car, J. and Atun, R. (2010) Integrating prevention of mother to child HIV transmission (PMTCT) programmes with other health services for preventing HIV infection and improving HIV outcomes in developing countries. The Cochrane Library.

- Munthali, A.C. (2006) Universal access indicators from Malawi: A final report.

- UNICEF (2009) Malawi’s children the missing face of AIDS.

- Bhuiya, I. (2004) Adolescent reproductive findings from intervention research in Bangladelsh.

- Buyungo, P. and Ategeka, J.A.K. (2005) HIV/AIDS TRAc study examining the use of prevention of mother to child transmission services among women of reproductive age. Research Division PSI, Kampala.

- Nguyen, T.A., Oosterhoff, P., Ngoc, Y.P., Wright, P. and Hardon, A. (2008) Barriers to access prevention of mother to child transmission for HIV positive women in a well-resourced settings in Vietnam. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=235891

- National Statistical Office and UNICEF (2008) Malawi multiple indicator cluster survey 2006, final report. National Statistical Office and UNICEF, Lilongwe.

- Ministry of Health (2008) HIV and syphilis sero-survey and national HIV prevalence and AIDS estimates report. Design Printers, Lilongwe.

- Braun, V. and Clarke, V. (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77- 101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Bajunirwe, F. and Muzoora, M. (2005) Barriers to the implementation of programs for the prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV: A cross sectional survey in rural and urban Uganda. AIDS Research and Therapy, 2, 10. doi:10.1186/1742-6405-2-10

- UNAIDS and WHO (2004) UN human rights guidelines. WHO, Geneva.

- Gama, J. (1999) A study on impact of AIDS education on condom use towards HIV/AIDS prevention among the youths at Mulanje secondary school. Unpublished Bachelors Dissertation, University of Malawi, Zomba.

- Mukuka, L. and Nevo, V.S. (2006) AIDS related knowledge, attitude, and behavior among adolescents in Zambia. Ethnicity and Disease, 16, 488-494.

- Moore, K.M. (2003) Linking women and communities with skilled childbirth care: Use of a community-designed birth preparedness card in Western Kenya [draft]. The CHANGE Project, Academy for Educational Development. The Manoff Group, Washington DC.

- Kasenga, F., Hurting, A.K. and Emmelin, M. (2007) Home deliveries: Implications for adherence to neverapine in a prevention of mother to child transmission programme in rural Malawi. AIDS Care, 19, 646-652. doi:10.1080/09540120701235651

- Leonard, A., Mane, P. and Rutenberg, N. (2001) Evidence for the importance of community involvement: Implications for initiatives to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV, in community involvement in initiatives to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV. The Population Council, Glaxo.

- Magoma, M., Requejo, J., Campbell, O.M.R., Cousens, S. and Fillip, V. (2010) High ANC coverage and low skilled attendance in rural Tanzanian district: A case for implementing a birth plan intervention. BMC Pregnancy and Child birth, 10, 1471-2393.

- Stringer, J.S., Sinkala, M., Stout, J.P., Goldenberg, R.L., Acosta, E. and Chapman, P. (2003) Comparison of two strategies for administering nevirapine to prevent perinatal HIV transmission in high-prevalence, resource-poor settings. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 32, 506-513. doi:10.1097/00126334-200304150-00007

- Medley, A.M., Kennedy, C.E., Lunyolo, S. and Sweat, M.D. (2009) Disclosure outcomes, coping strategies, and life changes among women living with HIV in Uganda. Qualitative Health Research, 19, 1744. doi:10.1177/1049732309353417

- Manhart, L.E., Dialmy, A., Ryan, C.A. and Mahjour, J. (2000) Sexually transmitted diseases in Morocco: Gender influences on prevention and health seeking behavior. Social Science and Medicine, 50, 1369-1383. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00398-6

- Colton, T.C. (2005) Preventing mother to child transmission of HIV in Kenya: Pathfinder internationals’ experience 2002-2005.

- Njunga, J. (2008) Infant feeding experiences of HIV positive mothers enrolled in prevention of MTCT programmes— The case for rural Malawi.

- Ministry of Health (2009) National sexual and reproductive health and rights policy. Ministry of Health, Lilongwe.

- Ayouba, A., Tene, G., Cunin, P., Foupouapouognigni, Y., Menu, E. and Kfutwah, A. (2003) Low rate of mother-tochild transmission of HIV-1 after Nevirapine intervention in a pilot public health program in Yaoundé, Cameroon. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome, 34, 274-280. doi:10.1097/00126334-200311010-00003