Modern Economy

Vol. 3 No. 1 (2012) , Article ID: 16836 , 9 pages DOI:10.4236/me.2012.31013

Corporate and State Social Responsibility: A Long-Term Perspective

Department of Economics and Statistics, University of Calabria, Arcavacata di Rende, Italy

Email: {r.lombardo, gio.dorio}@unical.it

Received October 16, 2011; revised November 20, 2011; accepted November 29, 2011

Keywords: Corporate Social Responsibility; Economics and Social Values; Meta-Externalities; Sustainability

ABSTRACT

Companies have caught the changes in consumer perceptions and have developed corporate social responsibility (CSR) as long run survival strategy. The CSR signals that companies are overcoming the logic of the short term. The question is whether an evolution towards something similar that we call State social responsibility (SSR) is possible. State social responsibility is exerted when the State, in absence (or in case of ineffectiveness) of a formal supranational law, protects the rights of current and future generations of its citizens and citizens of other states and/or raises the current generations’ awareness regarding the opportunities reduction generated in space and time by meta-externalities. States would signal the tendency to overcome their short-sighted logic if the meta-externalities became a crucial question in their agenda.

1. Introduction

Corporations are often accused of damaging the environment and it is not clear what should be the appropriate correction of the external effects they produce. Yet, a number of them adopt social responsibility practices, that is, go considerably beyond what is legally required and incur significant costs in order to minimize the environmental impact.

Is it socially desirable for managers to take costly environmental initiatives at the expense of shareholders? Companies have more than one reason for adopting environmentally responsible behaviour and ethical and economic motivations co-exist [1,2]. The reputation management approach, for example, considers the firm’s reputation as a sort of capital which represents the financial value of its intangible assets [3].

Two issues related to Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) are of particular interest. The first is whether and how far the self interested actions of individual economic agents in a market economy will promote the common good. The second concerns what can be done to make enterprise profitability a better indicator of social welfare.

The paper analyses the conditions that affect strategic decisions by firms adopting environmental CSR with the aim to understand if States might find it convenient to adopt, in turn, social responsibility practices. It proposes an attempt to specify how just an increase in the collective/ individual awareness of existing meta-externalities can be the driver toward an effective Social State Responsibility.

The most important reason why we look in a comparative way to the evolution of behaviour of State and firm regards the time span within which some problems occur and their solutions may be effective. The CSR signals that, in some ways, businesses are overcoming the shortterm logic. The pursuit of short-term objectives by states appears to be normal behaviour since politicians tend to favour policies that have short-run effects taking advantage of current generation myopia (see, for example, [4]).

If the issue of meta-externalities became central rather than marginal, i.e. if states provided an adequate balance of the apparently conflicting rights of current and future generations, then they would show the same tendency observed in recent firms’ behaviour to overcome the shortterm logic.

2. Corporate Social Responsibility

The CSR literature emerged as a criticism of the neoclassical theory which—based on the assumption that market forces and government will address harmful activities— postulates that companies should maximize their profits [5]. The term CSR was first formalized by [6] who argued that “it refers to the obligations of businessmen to pursue those politics, to make those decisions, or to follow those lines of actions which are desirable in terms of the objectives and values of society” (p.6). A crucial development of the definition of CSR is the work of [7] that included in the concept institutions and, thus, enterprises. This was because, up to that point, use of the term businessmen had implied that the owner of an enterprise was also its manager and, therefore, personally bore the cost of every social commitment.

At a distance of some decades, although many scholars assume that there is an inherent compatibility of profitmaking and fulfilling the needs of society, there is no consensus on the definition of CSR.

According to [8], CSR is “a concept whereby companies integrate social and environmental concerns in their business operations and in their interaction with their stakeholders on a voluntary basis”. A number of alternative approaches reflect different views on the utility of CSR into framing the role of business in society (see [9] for a review).

Even though there are various CSR area (i.e. environment management, labour relations, social and cultural activities, etc.) we focus on environmental issues because the role played by states and firms to solve meta-externalities is distinctive.

2.1. Drivers of Environmental CSR

If the enterprise succeeded in best serving the interest of all its stakeholders by focusing on the maximization of its profits and optimizing its process of production, then this focusing should take place under the conditions of perfect competition. Only these conditions, according to economic theory, assure the absence of dissociation between the economic and social frontiers of the firm.

Given this absence of dissociation between the economic and social frontiers and given that the market and the government regulate the firm, the responsibilities of this latter have generally been considered to be of a legal rather than a social character.

Even though, in theory, when the firm is solely preoccupied with its economic boundaries, it contributes to the general welfare, in the value creation process, it internalises some costs and transfers others to its stakeholders. The “social costs” or external costs represent costs which are necessary for the creation of value, but which are not assumed by the producer; rather they are borne by the stakeholders [10]. A portion of the profit generated by the firm is earned to the detriment of the stakeholders.

Environmental CSR refers to actions going beyond compliance, private provision of public goods, or voluntary internalizing of externalities. Its recent emergence has been attributed to pure market effects, simple externalities, and meta-externalities. The first two categories do not need much explanation. We define meta-externalities as unwanted side-effects of the whole economic system on its physical and social contexts. Climate change is perhaps the greatest negative meta-externality ever imposed by economic systems on the natural world.

The growing awareness of the stakeholder role that everybody has to play, together with market and political forces that are the actual drivers of firms environmental CSR, may stimulate the diffusion of environmental CSR initiatives.

If the firm is involved in short-term wealth transfers, it must recover that value from somewhere—either by increasing its revenues (e.g. by increasing the willingness to pay) or by reducing the cost of its inputs. Market forces include win/win opportunities to increase revenues with green consumers who are willing to pay a higher price as a premium for environmentally-friendly products and to cut costs by improving the efficiency of resource use, labour market advantages with employees who have green preferences [11-13]. The pure market effects emerge from a company that has done just what it was supposed to do.

Corporate care of the environment and support of socially responsible programs play an increasingly influential role in consumer purchasing behaviour, according to the first Global Survey [14] on company ethics and corporate responsibility released by The Nielsen Company. Half the world’s consumers (51%) consider it very important that companies improve their environmental policies. In addition, 42% of consumers place high importance on fostering programs that contribute to improving society.

Firms that have chosen an environmentally proactive strategy may be able to lower operating costs in many different ways. More environmentally correct behaviour may translate into the ability of a firm to attract highly qualified workers while decreasing turnover, recruiting and training costs. The possibility of litigation and that of environmental accidents are reduced. Reducing externalities affects the firm capacity to obtain credit. Lenders and rating agencies scrutinize a firm’s environmental record, responsibility and risk. A more environmentally responsible firm will, all other things equal, receive a higher credit rating and it will have the opportunity to attract capitals from green investors at a reduced cost as well.

According to [15], companies that reduce the potential for conflict between themselves and the rest of society by reducing external effects may be rewarded on the stock market, which seems averse to companies with bad environmental records.

Being environmentally conscientious might involve greater investment in technology, methods and raw materials than it is the case for the environmentally indifferent. However, it may also be claimed that this investment will bring advantages in a number of ways, resulting, in the end, in increased profits1.

Accordingly, adopting environmentally conscious behaviour becomes a source of technological innovation that brings advantages to companies as well as society.

Political forces may be summarized as effective regulatory threats, enforcement pressures, or threats of boycott from non-governmental organizations (NGOs).

Firms over-comply to reduce the risk of tighter regulation, or to induce the government to choose a form of regulation which is more favourable for them [1,17]. Factors such as managerial altruism and the emergence of a new generation of savvier business leaders who take pro- active steps to avert political conflict should not be disregarded.

Poor corporate performance is often targeted by local community and customer activists because of its associated negative externalities, and non-compliance with environmental laws may elicit coercive pressure in the form of penalties imposed by government regulators. A reputation for being environmentally considerate can enhance a company’s image in the eyes of consumers and improve its relations with regulators.

Although an environmentally responsible strategy has costs associated with it that, as [18] argue, have often been emphasized, benefits come with such a strategy too and these have usually been discounted or completely ignored.

2.2. The Influence of CSR on Welfare

In order to provide benefits to shareholders, any investment must increase customers’ willingness to pay or reduce costs in some circumstances.

In the debate about the relationship between firms’ environmental and economic performance, it is often argued that there is a conflict between firms’ competitiveness and their environmental performance [19].

At the level of a specific industry, for example, the proportion of environmental costs to total manufacturing costs might be higher than the average for manufacturing as a whole [20]. Since, in the past, firms focused on endof-pipe technologies as the major approach towards pollution control and environmental performance improvements in general, environmental investments were often seen as an extra cost [21]. The notion has emerged rather late that improved environmental performance is a potential source of competitive advantage as it can lead to more efficient processes, improvements in productivity, lower costs of compliance and new market opportunities [16]. Two major factors support this argument. First, companies facing high costs for their polluting activities have an incentive to carry out research into new technologies and production approaches that might reduce the costs of compliance. Resulting innovations might lead to lower production costs, e.g. lower input costs due to enhanced resource productivity. Second, companies can also gain “first mover advantages” from selling their new solutions and innovations to other firms [22]. In a longerterm perspective, the ability to innovate and to develop new environmentally sound technologies and production approaches is likely to be a key determinant of competitiveness, alongside the more traditional factors of competitive advantage [23].

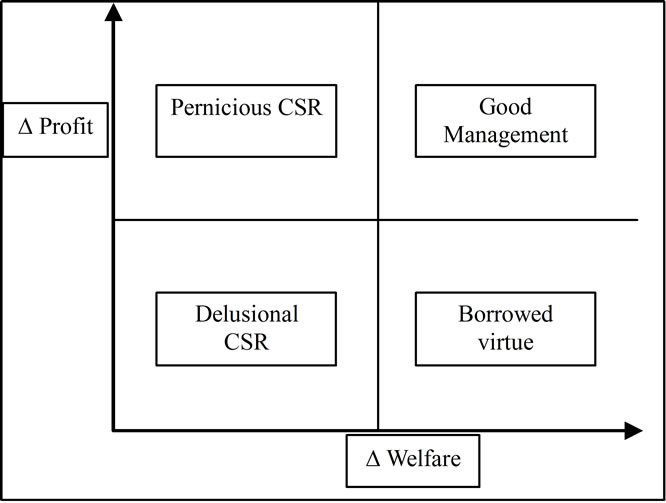

As shown in the Figure 12, the most successful CSR projects are those that deliver solutions which are both profit and welfare enhancer (Good Management). The worst CSR projects are those that carry out solutions which are on the opposite direction (Delusional CSR). However, we can not exclude a trade-off between pursuing the two objectives at once (Borrowed CSR virtue and Pernicious CSR). To summarize, there is no guarantee that CSR enhances social welfare: the welfare effects of CSR are situation-contingent. CSR can potentially decrease production inefficiencies and, at the same time, allow companies to increase sales and give increased access to capital and new markets. Some activities result in immediate cost-saving while other activities bring reputational benefits to the company which increase both profitability and market valuation in the long-term or dissuade the Government from future action which might impose significant costs on the company. On the one hand, the private sector generally prefers the flexibility of self-designed standards. On the other hand, regulation in itself is, as we will see in Section 3.1, unable to cover every aspect in a corporation’s functioning in detail.

3. State Social Responsibility

States, such as companies, may promote new social trends. However, whereas states—unlike companies—will survive anyhow, politicians, in order to be re-elected, must engage in a behaviour that is beneficial to current generations; they adopt a short-run logic.

Figure 1. CSR, welfare and profit.

Considering CSR as the most recent evolution in businesses, we ask ourselves if there is a tendency towards a similar change in the behaviour of the State. Is there a potential for a behaviour by the State that exceeds what can be described as its classic function? In other words, is there an evolution towards a State Social Responsibility? Before trying to give an answer to this question we give our definition of Social State Responsibility.

The responsibility of the State is the obligation to ensure the protection of those inalienable rights which are inherent human nature (such as those to life, health, etc.). This can be seen as the classical function of a State3.

The responsibility of the State becomes state social responsibility4 (SSR) when the State, in absence (or in case of ineffectiveness) of a formal supranational law, protects the rights of current and future generations of its citizens and citizens of other states and/or raises the current generations’ awareness regarding the opportunities reduction generated in space and time by meta-externalities5.

A pro-active behaviour—as, for example, to encourage new supranational agreements or, when the tools to ensure the protection of the rights are ineffective, to activate itself in order to ensure the full enjoyment of the rights of present and future generations even beyond the national boundaries—transforms the responsibility of the State in SSR.

Meta-externalities are unwanted side-effects of the whole economic system on its physical and social contexts-effects in which the economic culture fouls its own nest, if the “nest“ is understood broadly as being all the contexts in which humans live [25].

Therefore, if the responsibility of the State becomes SSR when it encompasses State initiatives beyond its classical function, it is evident that there is a potential for a SSR in relation to many issues. In this paper, we focus mainly on environmental concerns.

Market economies try to increase well-being pursuing the goals of maximizing profits, production and consumption. The maximizing of the desirable output (GDP) is accompained by the stabilization or increase of undesirable byproducts (CO2 emissions, for example), i.e. it contributes to the production of meta-externalities. Many people in rich countries, and some elites in poor countries, could actually be better off with less stuff. Reduced material throughout the global economy would help, for instance, with climate change mitigation; at the same time, resilience and social cohesion would be increased by policies that depress conspicuous consumption and encourage societies to define success in terms other than material possessions.

Nevertheless, many governments seem nowadays to be oriented in doing what is in the interest of some minority lobbies, rather than working for the general, long-term well-being of people and environment protection.

It is not simple at all to include the loss of welfare in the calculations of externalities; with meta-externalities the complexity becomes higher.

The increasing diffusion of the meta-externalities probably prevents future generations to have the same opportunities we have had. Furthermore, social and economic conditions have produced others factors of unsustainability; therefore, a moral and ethical reorientation of public and private choices, attitudes and behaviours may help.

In our view, the complex issue of meta-externalities is crucial and it is in trying to limit them that one sees the need/opportunity for a socially responsible behaviour by states.

Solving the issue of meta-externalities requires, in fact, a change in the mechanisms of production and consumption (and CSR works in this direction) and a not myopic behaviour viewed as a mixture of self-interest and of concern for other people and/or the next generation. If SSR promotes not short-sighted social trends, it may contribute to the development of moral norms that will be internalised by individuals and, doing so, it will probably make policy choices sustainable, not biased by myopia. Therefore, several tools6 are required to better govern the relations between the countries, to guarantee sustainability, social justice, respect for human rights.

3.1. Weaknesses of Regulation and Voluntary Agreements

State regulation is binding and can play an important role in bringing about environment friendly behaviour by firms. It is not perfect, however, and it may even end up reducing public welfare because of its cost or inefficiency.

Regulations to control emissions of environmental pollutants have been criticized for being costly and inefficient. Inefficiencies associated with government interventions in many developing and even advanced economies are well known7. The presence of government corruption is interpreted by some social scientists as evidence that most politicians try to further their career or wealth rather than correct market failures (e.g., [28,29]). Most legislation, especially that concerning the environment, establishes general objectives but leaves the details of implementation to a regulatory agency. Even when legislative mandates are communicated clearly to regulators, discrepancies between the wishes of the principal (the legislature) and the agent (the regulator) can not be excluded. For example, [28] argues that a key motivation for bureaucrats, including regulators, is the maximizing of their budgets, something that is not the objective of the legislature. Regulators also have future career concerns that may involve obtaining a position within the regulated industry or running for elected office [30].

Even after regulations are promulgated and their implementation has been delegated to a regulatory agency, they are unlikely to have much impact on corporate behaviour unless government undertakes costly monitoring and enforcement activity. Regulatory agencies are chronically under-funded, which means that regulators must carefully allocate their enforcement resources. As a result, companies viewed by regulators as socially responsible are likely to be monitored less frequently. This could not exactly be a good result for social welfare.

A normative framework must identify both a social welfare improvement and the parties which have the duty or responsibility to respond to it. From a utilitarian perspective when transactions costs are high, the duty should be assigned to the party that can most efficiently di- minish the externality [31].

States can, alternatively, tax firms that pollute excessively but, often, they fail.

It has been argued that environmental regulation enhances economic performance in an efficiency-producing, innovation-stimulating symbiotic relationship. On the other hand, regulations are criticized as generating costs that businesses will never recover and these represent financial diversions from productive investments [19].

Companies could address social responsibility issues in a more efficient and productive manner if they are allowed to do so by themselves—voluntarily—and not in response to government regulations. Any external imposition of fines or additional compliance costs would drive down profits. The relationship is, however, more complex than a simple calculus equating higher costs with lower profits.

CSR practices may pre-empt legislation if they are adopted early in the life cycle of the policy; if adopted later in the cycle, they may influence the stringency of regulations that cannot be pre-empted.

Environmental voluntary agreements (VAs) are quite different from traditional regulatory instruments since they are based on the exchange between the regulator and a firm (or an industry) and on the design of an incentives framework to parties in a context of cooperation.

A firm adopts a VA if it raises its profits, that is if it is accompanied by a shift in either the demand or supply curve or both [32]. Where the demand effect is predominant, the motive for its adoption is to capture the consumers’ willingness to pay for the environmental attributes of a product. VAs become differentiation strategies. This may increases firms’ profits, thus providing them with an incentive to voluntarily abate emissions.

VAs can be thought of as a way to increase a firm’s reputation vis à vis imperfectly informed consumers who give an additional value to environmentally friendly products or processes, but are unable to assess the quality of the products they purchase. When firms can choose their emission technology and consumers do not have complete knowledge of the environmental benefits, the VA can be seen as a choice by the “greener” firms to engage in non-mandatory abatement levels. The less environmentally efficient firm will meet the already existing standards.

A VA adoption by firms with low abatement costs might be aimed at “inducing regulation”. If a firm can reduce pollution more cheaply than other firms in its industry, it might wish to bring about a situation in which all of the firms in the industry have to reduce pollution and face the consequent increase in costs. One way to do this is to encourage government authorities to force collective action [33]. The efficient firm will, hence, gain a greater market share for itself. Therefore these agreements may have anticompetitive effects. As it is well known, market structure affects social welfare.

VAs can be a strategic variable through which firms might avoid lobbying conflicts or, at least, make them less intense. When firms self-regulate, in fact, they reduce consumers’ incentives to undertake lobbying activities. Given that lobbying conflicts can be seen as an unproductive expense, this is another argument in favour of VAs.

Anyway, self-regulation works better in a culture that honours integrity and concern for others at least as much as it respects success in making money. Unfortunately many cultures have drifted away from this position, so rendering external regulation more necessary.

3.2. Environmental Meta-Externalities and Ineffectiveness of Current Solutions

The transfer of social and environmental costs to stakeholders is still an endemic practice in many firms. In many countries, environmental policies and regulations have been implemented to improve poor environmental conditions. The last three decades have seen the establishment of numerous international norms and standards for environmental protection8.

Since the beginning of the nineteen eighties, firms have made a radical change in their production processes: they have decentralised and globalized. As a result of this transformation, market and governments have become incapable of reducing the gap between the economic and social boundaries of the firm. Therefore, unwanted sideeffects of the whole economic system impose a reflux of “social cost” on stakeholders.

What should we do? There can be two different answers: the simplest one is to internalize the externalities —that is, find some way to ensure that the economic actor that generates costs has to pay them all; the hardest, but probably the most effective, is to avoid that externalities are created.

Self-regulation can be a way to avoid that some externalities are generated since regulation by entities outside of a corporation, as we saw, can only partially prevent it to externalize its costs. Furthermore, self-regulation efficacy requires integrity and concern for others.

Critical meta-externalities reflect the impact of the economic system on the social context. Politicians and their stakeholders need to care about the long run, and to be able and willing to address intelligently the complex issues that face modern societies. Selfishness, short-term thinking and impatience with complexity are cultivated in the population at large, but these are not the characteristics that will best contribute to a healthy society or a healthy economy.

The concern about one of the most important metaexternalities actually faced emerged on an international scale for the first time during the World Climate Conference held in Geneva in 1979.

The magnitude of the impacts, the planetary scale of the challenge and the consequences for future generations are more than sufficient reasons to demand an institutional architecture able to regulate the intervention of private and public players.

The failure of Copenhagen, for example, was not the absence of a legally binding agreement but the absence of an agreement about how to achieve the noble goal of saving the planet. There was no agreement about reductions in carbon emissions, on how to share the burden, and no agreement on help for developing countries. Even the commitment of the accord to provide amounts close to $30 billion for the period 2010-2012 for adaptation and mitigation appears trifling compared to the hundreds of billions of dollars that have been distributed to the banks in the bailouts of 2008-2009. If that much can be laid out to save banks, something more can be laid out to save the planet [34].

Dramatically increasing public funding would help to solve many of the political challenges which the Kyoto approach presents but the solution of this meta-externality requires a more effective common policy (not just rules) at world level.

Despite a rich production of declarations and international standards, human rights are often violated. When this happens in a State, other states can intervene, but doing so they violate its sovereignty. To overcome this limitation, after the Second World War, thanks to the role played by the UN and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, several states have signed agreements that recognize their citizens’ right to resort to international tribunals to seek justice.

The responsibilities of present generations have been spelled out, among others, in the Declaration adopted by the General Conference of the United Nations for Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (Paris, 12 November 1997) in particular in Articles 4 and 5.

Rules that protect the fundamental rights of the person are countless in international treaties. One must therefore ask whether the protection of human rights, enunciated by regulations, both in national law and in the international treaties, is actually guaranteed.

The enunciation of legal rules can not define reality in its completeness, in all its multiple variants. Formal rules therefore have to be complemented by more specific provisions, which adapt to the situation substantially.

A perfect legislation on the abstract cannot match a real safeguard of some rights, when the moral standard is not aligned. The correct application of the law assumes that moral values are actually lived and followed within the Society. It is the implementation of moral values that guarantee the rule of law, not the opposite. The law must ensure compliance with ethical principles, but is itself conditioned, in its level of application, from the moral level of the judicial bodies—and then essentially of the Society—which is addressed.

4. Stakeholder Theory: Private and Public Responsibilities

The opportunity for a more effective organization of firms’ internal use of resources and for a reduction of the risk of tighter regulation, are not the sole explanations for the rationale behind CSR. The firm is dependent on a number of core stakeholders whose acceptance and support is instrumental for its success.

According to mainstream stakeholder theory [35-37], ethical, non-economic considerations must be taken into account in the appropriate management of business enterprises even though they cannot be encapsulated in stakeholder theory. Stakeholders have different interests in preserving the environment. According to [38], balancing stakeholder interests promises little progress in the area of the environment. Broad stakeholder theories offer no concrete proposals about how competing and conflicting interests should be balanced in general.

CSR is about treating the stakeholders of a corporation in an ethical and socially responsible manner [39]. In our view, SSR is about treating the stakeholders of a nation in an ethical and socially responsible manner. The key stakeholders of any State are the current and future generations of the whole international community.

There are more than 500 global agreements on environment and, at the same time, many organizations try to protect it. However, the environment continues to be damaged. We cannot say if the cause of this is a lack of political will or an absence of social norms, but countries that have departed from acting in a socially responsible way might learn from CSR practices to treat their stakeholders responsibly. Companies, in fact, proactively integrate the voice of parties affected by business activities in corporate decision making and voluntarily take further steps to improve the quality of life for employees and their families as well as for society as a whole.

Can a meta-externality such as, for instance, an unsafe and unhealthy environment for current and future generations be seen as a violation of a human right? If the answer to this question is yes, then the State’s “social” responsibility has to include all those actions deemed necessary to protect the environment.

The dividing line between economic problems that are open to estimation and moral problems that are not, depends on a number of factors which are different for different cultures. So the relevant question is to include all of the culturally relevant factors among the relevant variables, even if they are not measurable through standard techniques, and to decide which is the most important aspect to be pursued. In this way, if a situation is presented in an ethical light, the goal will be to find the best ethically correct decision. On the other hand, when a situation is presented in a managerial light, the goal will be to find the best decision for the manager. Furthermore, when making moral judgment to evaluate various alternatives, an ethical point of view activates an ethical schema, such as Personal Interest or Maintaining Norms [40], which is different from what a managerial point of view activates (e.g. an economic rationality schema) to make a managerial judgment [41].

The adoption of CSR practices demonstrates that companies consider not only economic variables in general and profits in particular as relevant in order to estimate the “value” of an investment or the value of a policy, they also try to consider moral questions that can influence welfare.

Furthermore, by considering as relevant variables those which are usually considered as merely moral matters, companies try to move the dividing line further. An analysis which, refining the concept of profit, can offer a sketch of a larger set of variables is useful in order to understand the effects of phenomena that are not merely economic. To better understand this point, let just consider the vote on the nuclear energy in Italy. Supporters of nuclear energy tried to convince government stakeholders that they could save the 30 percent (short run economic rationality approach) on electricity bill with the nuclear option. Citizens used a larger set of variables to decide their vote and the nuclear option was rejected.

Firms implemented CSR as a long run survival strategy when they understood that the “customers” had some specific perception on the fact that corporations have an obligation to conform to the basic rules of the society, both those embodied in law and those embodied in ethical custom [42].

If the government acts in a way that is, or might be, adverse to future generations, it becomes necessary to weigh the impact of that action on current generation or, at the same time, to balance it with correlated actions that will benefit future generations. The difficulties with this approach are, for the current generation, to estimate a correct discount rate that will signal the importance of the future to estimate overall consequences of the action in terms of welfare and to put in place all the log-rolling interlocked actions that will mitigate eventual negative effects on future generations until the overall value of the action gives positive, overlapping generation, welfare effects.

5. Concluding Remarks

The idea behind this paper is that, in addition to a company which evolves and carries out its activities beyond what is required by law, we need a State which goes beyond what is required by State Responsibility in its operations. In our view, this co-evolution can promote new social trends which are able to ensure the welfare of present and future generations.

CSR considers two things as relevant: the firm’s stakeholders’ welfare and shareholders’ profit and tries to reconcile the apparent trade-off with visions that make long run profit correlate to the welfare of all stakeholders.

The shift from short term to long term perspective in business is important and is becoming also accepted. The role of State in this is obviously a next and important step. If CSR has represented a shift in thinking of business, then the shift towards what is being called sustainability, is also like to move into the government and political arena.

States have inherent responsibilities in respect of social welfare in ways that companies don’t. Although companies face pressures from financial markets for quarterly earnings reports, CEOs have stock options that tie their earnings to the fortune of the firm etc.—all factors that drive much greater short-terminism in business than we see in politics—they pursue CSR practices as medium/ long run survival strategy.

Some advocates claim that CSR helps to meet objectives that produce long-term profits, while others claim that CSR is a step towards a decent society because companies are doing what is ethically correct. But, as we have seen, CSR initiatives, even the profitable ones, do not necessarily enhance social welfare.

Corporations, even when seeking to maximize profits by adopting a CSR approach, have no duty to guarantee the interests of society as a whole. Collective actions are often required to solve certain meta-externalities problems.

Public policies are far from efficient. If legislators and regulators actually pursue the public interest, the mixture of VAs and government regulation may help the system to work at a higher level of welfare. The implementation of measures to fight meta-externalities which are effective in the medium long-term requires agreements sought, entered into and supported by different players. All stakeholders (international community, including enlightened States, national and local governments, firms, etc.) have a fundamental role.

If the approach of “long term” to the profit is at the base of the CSR, this means that companies are acting voluntarily because they have understood that giving up a higher profit, in the short term, is more convenient if the consequence of pursuing it, probably, leads to a demise in the long run.

This is true for all non-hit and run firms. By analogy, if the welfare of future generations matters for each single State, then it will push policy towards actions that are socially responsible.

A clear perception by citizens that the presence of some meta-externalities violates their fundamental rights can help in reducing them. The State can stimulate this perception in different ways such like:

· reducing the contradictions in the existing agreements, by stating unambiguous objectives, and making them more effective;

· allocating sufficient resources that should be used efficiently by implementing every possible synergy and avoiding duplications;

· making easier the appeal to the Court of Justice (reducing its costs, promoting collective action by specific associations, facilitating the spread of specific communication campaigns to reduce information asymmetries existing with respect meta-externalities);

· making more effective the results produced by judgments.

In turn, citizens have it in their hands to support (or not) the managers of firms by buying (or not) their products. In the same way, citizens have the possibility to support (or not) politicians at elections. Therefore the role of citizens is crucial and, if played well, will contribute to the implementation of long-term policies and structural changes. In fact, although there is not a single answer to the question of how to define and shape a desirable and sustainable path of economic development, one important starting point for change is cultural, and not necessarily responding to the social trends promoted by States.

6. Acknowledgements

We would like to thank two anonymous referees for useful comments and suggestions. The usual disclaimers apply.

REFERENCES

- J. W. Maxwell, T. P. Lyon, and C. Hackett, “Self-Regulation and Social Welfare: The Political Economy of Corporate Environmentalism,” Journal of Law and Economics, Vol. 43, No. 2, 2000, pp. 583-618. doi:10.1086/467466

- J. Levis, “Adoption of Corporate Social Responsibility Codes by Multinational Companies,” Journal of Asian Economics, Vol. 17, No. 1, 2006, pp. 50-55. doi:10.1016/j.asieco.2006.01.007

- C. J. Fombrun, “Reputation—Realizing Value from the Corporate Image,” Harvard Business School Press, Boston, 1996.

- T. Fujii, “Environmental and Resource Management Under miopia,” SMU Economics and Statistics Working Paper No. 26, Singapore Management University, Singapore, 2006.

- P. Heugenes and N. Dentchev, “Taming Trojan Horses: Identifying and Mitigating Corporate Social Responsibility Risks,” Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 75, No. 2, 2007, pp. 151-170. doi:10.1007/s10551-006-9242-y

- H. Bowen, “Social Responsibility of the Businessman,” Harper and Row, New York, 1953.

- K. Davis, “Understanding the Social Responsibility Puzzle: What Does the Businessman Owe to Society?” Business Horizons, Vol. 10, No. 4, 1967. pp. 45-50. doi:10.1016/0007-6813(67)90007-9

- European Commission Green Paper, “Promoting a European Framework for Corporate Social Responsibility,” EMCC, Dublin, 2001.

- L. Siegele and H. Ward, “Corporate Social Responsibility: A Step towards Stronger Involvement of Business in MEA Implementation?” Review of European Constitutional and International Environmental Law, Vol. 16, No. 2, 2007, pp. 135-144. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9388.2007.00552.x

- R. Coase, “The Firm, the Market and the Law,” Chicago Press, Chicago, 1988.

- S. Arora and S. Gangopadhyay, “Toward a Theoretical Model of Voluntary Overcompliance,” Journal of Economic Behaviour and Organisation, Vol. 28, No. 3, 1995, pp. 289-309. doi:10.1016/0167-2681(95)00037-2

- M. Bagnoli and S. Watts, “Selling to Socially Responsible Consumers: Competition and the Private Provision of Public Goods,” Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, Vol. 12, No. 3, 2003, pp. 419-445. doi:10.1162/105864003322309536

- S. Lutz, T. P. Lyon and J. W. Maxwell, “Quality Leadership When Regulatory Standards Are Forthcoming,” Journal of Industrial Economics, Vol. 48, No. 3, 2000, pp. 331-348. doi:10.1111/1467-6451.00126

- Nielsen Group, Nielsen Global Survey, Regional EEMEA, 2008.

- G. Heal, “Corporate Environmentalism: Doing Well by Being Green,” Working Paper, Columbia Business School, New York, 2007.

- M. E. Porter and C. van der Linde, “Toward a New Competition of the Environment-Competitiveness Relationship,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 9, No. 4, 1995, pp. 97-118. doi:10.1257/jep.9.4.97

- K. Segerson and T. Miceli, “Voluntary Approaches to Environmental Protection: The Role of Legislative Threats,” In: C. Carraro and F. Lévêque, Eds., Voluntary Approaches in Environmental Policy, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, 1999.

- R. J. Curcio and F. M. Wolf, “Corporate Environmental Strategy: Impact upon Firm Value,” Journal of Financial and Strategic Decisions, Vol. 9, No. 2, 1996, pp. 21-31.

- N. Walley and B. Whitehead, “It’s Not Easy Being Green,” Harvard Business Review, Vol. 72, No. 3, 1994, pp. 46- 52.

- R. Luken, R. Kumar and J. Artacho-Garces, “The Competitiveness of Selected Industries in Developing Countries,” Proceedings of the 5th Greening of Industry International Conference, Heidelberg, 24-27 November 1996.

- M. A. Cohen, S. A. Fenn and J. Naimon, “Environmental and Financial Performance: Are They Related?” Vanderbilt University, Nashville, 1995.

- D. Esty and M. Porter, “Industrial Ecology and Competitiveness Strategic Implications for the Firm,” Journal of Industrial Ecology, Vol. 2, No. 1, 1998, pp. 35-43. doi:10.1162/jiec.1998.2.1.35

- M. Wagner, N. Van Puh, T. Azomahou and W. Wehrmeyer, “The Relationship between the Environmental and Economic Performance of Firms: An Empirical Analysis of the European Paper Industry,” Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, Vol. 9, No. 3, 2000, pp. 133-146. doi:10.1002/csr.22

- The Economist, “The Union of Concerned Executives, CSR as Practised Means Many Different Things,” The Economist (US), Vol. 374, No. 8409, 2005.

- N. Goodwin, “Internalizing Externalities: Making Markets and Societies Work Better,” Opinion Survey, No. 52, 2007.

- D. Lal, “The Poverty of Development Economics,” Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 1985.

- H. De Soto, “The other Path: The Invisible Revolution in the Third World,” Harper, New York, 1989.

- W. A. Niskanen, “Bureaucracy and Representative Governments,” Aldine-Atherton Press, Chicago, 1971.

- A. Shleifer and R. W. Vishny, “Politicians and Firms,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 109, No. 4, 1994, pp. 995-1026. doi:10.2307/2118354

- T. P. Lyon and J. Maxwell, “Environmental Public Voluntary Programs Reconsidered,” Policy Studies Journal, Vol. 35, No. 4, 2007, pp. 723-750. doi:10.1111/j.1541-0072.2007.00245.x

- D. P. Baron, “A Positive Theory of Moral Management, Social Pressure, and Corporate Social Performance,” Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, Vol. 18, No. 1, 2009, pp. 7-43. doi:10.1111/j.1530-9134.2009.00206.x

- R. Brau and C. Carraro, “The Economic Analysis of Voluntary Approaches to Environmental Protection. A Survey,” CRENos Working Paper, Sardinia, 2004.

- F. Reinhardt, “Market Failures and the Environmental Policies of Firms. Economic Rationale for Beyond Compliance Behavior,” Journal of Industrial Ecology, Vol. 3, No. 1, 1999, pp. 9-21. doi:10.1162/108819899569368

- J. E. Stiglitz, “Overcoming the Copenhagen Failure Project Syndicate,” 2010. www.project-syndicate.org.

- R. E. Freeman, “Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach,” Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, 1984.

- T. Donaldson and T. W. Dunfee, “Ties that Bind: A Social Contracts Approach to Business Ethics,” Harvard Business School Press, Boston, 2000.

- T. S. Nair and R. Pradhan, “Binding Stakeholders into Moral Communities: A Review of Studies on Social Responsibility of Business,” MAPRA Paper No. 20767, Munich, 2010.

- E. W. Orts and A. Strudler, “The Ethical Environmental Limits of Stakeholder Theory,” Business Ethics Quarterly, Vol. 12, No. 2, 2002, pp. 215-233. doi:10.2307/3857811

- M. Hopkins, “The Planetary Bargain: Corporate Social Responsibility Matters,” Earthscan Publication Ltd., London, 2003.

- J. Rest, D. Narvaez M. Bebeau and S. Thoma, “A NeoKohlbergian Approach: The DIT and Schema Theory,” Educational Psychology Review, Vol. 11, No. 4, 1999, pp. 291-324. doi:10.1023/A:1022053215271

- V. N. Awsthi, “Managerial Decision Making on Moral Issues and the Effect of Teaching Ethics,” Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 78, No. 1-2, 2007, pp. 207-223. doi:10.1007/s10551-006-9328-6

- M. Friedman, “The Social Responsibility of Businesses Is to Increase Its Profits,” New York Times Magazine, New York, 13 September 1970, pp. 32-33.

NOTES

1[16] provide several examples of firms that increased the efficiency of their use of resources and reduced pollution and costs at the same time.

2Inspired by a diagram presented in [24].

3Many authors have different opinions about the function of the State, from minimal state to centralist state, (Hobbes, Nozick, Rawls, Marx, among others). We do not discuss here the different positions. We limit ourselves to give our definition.

4Social Responsibility since Society as a whole overcomes the boundary of a State in space (other States) and time (future generations).

5The result obtained by an effective SSR, in this case a merit good, will help to reduce the myopia of current generation.

6Lines of action, guidelines, policies, etc.

7See [26] on misallocation of resources; [27] on corruption.

8These have taken the form of treaties, conventions and multilateral environmental agreements (MEAs). It is unlikely that the implementation of many MEAs will be achieved through public initiatives alone [9].