Psychology

Vol.05 No.15(2014), Article ID:51096,6 pages

10.4236/psych.2014.515189

Changing Thoughtforms

David Klugman

Nyack Psychotherapy Group, Nyack, NY, USA

Email: spleeno@aol.com

Copyright © 2014 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 4 August 2014; revised 2 September 2014; accepted 26 September 2014

ABSTRACT

The author introduces and defines the idea of thoughtforms and their role in psychic life. Using both clinical and theoretical data to build his argument, the idea is put forward that dominant thoughtforms can be displaced by new ones, and that this is in fact the process of growth in both life and psychotherapy.

Keywords:

Thoughtforms, Sensation, Affect, Feeling, Cognition

1. Introduction

In this article I want to explore the nature of change in the human psyche based on what I will call thoughtforms. I will start with a definition of the term as I intend to use it, and focus primarily on those thoughtforms that grow out of our early experience and conditioning in childhood. My basic notion in doing so is that the thoughtforms that develop initially will become dominant thoughtforms and will continue to dominate in adult life to the extent that they remain unexamined. Conversely, to the extent that they are analyzed and “worked through” these early, dominant thoughtforms can be displaced by more profitable ones.

2. What Is a Thoughtform?

A thoughtform has many definitions, ranging from the psychological to the spiritual. Rather than providing the reader with a survey of what these definitions are (you can find them for yourself easily enough on the web): I am going to start by being very specific about what I mean by the term thoughtform as I will use it throughout this paper.

First, a thoughtform is not only made-up of thought. Rather a thoughtform is better conceived of as a condensed packet of psychic energy with a history of its making embedded within it. A thoughtform as I use the term can also be seen as an attitude or general orientation toward life, much of which is usually unconscious and procedural—that is, the attitude or orientation or thoughtform clicks into gear so automatically we do not notice it; it often takes on the appearance of “this is just the way things are”. Of course, speaking psychologically, there is no set “the way things are”, but rather the way things are, or the way the world appears, according to what one has experienced, learned and embedded within their psychic makeup. My focus in this section is to examine the way a dominant thoughtform comes into being.

3. How Thoughtforms Come into Being?

Let’s begin by stating the obvious: we are all living and trying to make sense of living at the same time. We know the rules and norms of our culture but we do not know the ultimate laws and reasons for living (i.e. the meaning of life). Nevertheless, we live meaningful lives largely to the extent that we live according to the thoughtforms that helps us make sense of our experience. In this regard a thoughtform can be profitably conceived of as a combination of presuppositions, imagery, and vocabulary current at a particular time or place and forming the context for experiencing the world. In other words a thoughtform is a commanding worldview that determines how we perceive and interpret our experience.

Democracy is a thoughtform: we’ve got the constitution, the flag, and the presupposition of freedom that underlies it. The effect of the thoughtform is that we see the world as a place of possibility rather than enslavement. At least that’s the ideal.

As I stated, however, I want to focus on the kinds of thoughtforms that grow up out of our experience in childhood and subsequently determine the aperture of our emotional availability to ourselves, the world, and the interaction between the two.

In this respect I would want to say that thoughtforms produce moods, feelings and attitudes about what’s possible in our lives. They can be limiting or expansive. They are, to repeat: commanding worldviews that determine how we perceive and interpret our experience. After exploring what goes into making up a thoughtform, I will explore what it takes to change or displace a limiting thoughtform with a more expansive one. First let’s start at the beginning.

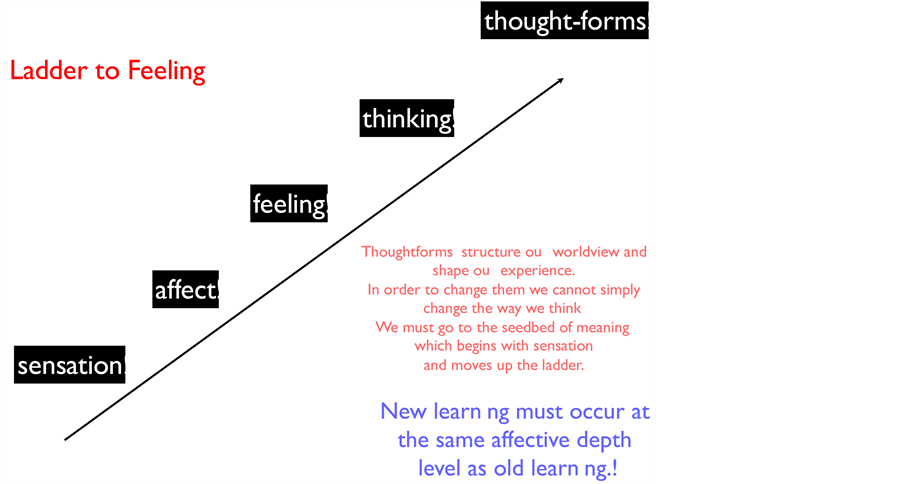

We are born into a world of sensations, and our capacity to take in these sensations from the moment of birth (perhaps even earlier) is immense ( Schore, 1994 ). So this is our baseline, sensations of all sorts and manner are taken in and processed by the infant ( Meltzoff, 1993 ). From sensation we move to affect, and by affect here I refer to not only the facial displays that have been well outlined by Darwin ( Darwin, 1965 ) and Tomkins ( Tomkins, 1970 ), but what Daniel Stern ( Stern, 1985a, 1985b ) refers to as vitality affects ( Stern, 1985a, 1985b ). These to me are in fact the more important affective components because they are conceived of as internal shifts or waves, surges and fadings, expansions and contractions that are sensually based but are more than just sensation as they have the beginning of what will emerge next, namely feeling. Feelings, then, arrive on the scene, after affects and sensations, and are discernable states that will eventually get names and be shared with others much more so than sensation and affect which, while they can also be named, are less likely to be shared through language. So, after sensation, affect and feeling come online, and after language has been acquired, the phenomenon of thinking and naming appears. Now keep in mind this is a very general chart or ladder I am outlining here and there is a great deal I am leaving out, as well as an enormous amount of research still going on pertaining to these early stages ( Beebe, Jaffe, & Lachman, 1992 ; Beebe & McCrorie, 1996 ; Schore, 1996 ; Tronick & Cohn, 1989 ; Tronick, Als, & Adamson, 1978 ; Tronick & Adamson, 1980 ; Zeanah, 1989 ). But for my purposes, however simplistic this map may appear, I find it useful to think in terms of moving from: sensation to affect to feeling to thinking. These four components, then, are what eventually produce what I am calling a thoughtform, and each component has to be addressed and accounted for if we are to understand the process completely. Let me give a brief clinical example to illustrate.

Case Study #1

Jenny grew up as an only child, and the basic psychic architecture of her childhood world was comprised initially by the fact that she had a depressed mother and a father who, although he adored her, was away a lot of the time. So Jenny’s primary experience was that of being with very less than average responsiveness in her environment. Mother tried but just didn’t really have it in her, due to her depression, to perform the vital mirroring functions that are so important for a child’s early sense of self, and subsequently self-worth ( Kohut, 1977 ).

A child’s psychic needs at the beginning of life are pretty basic, but foundationally important ( Stettbacher, 1991 ). Central among those needs is the need to feel seen ( Kohut, 1971 ). Accordingly, if the primary source for the fulfillment of that need is impaired in some way the child’s need to feel seen is sorely compromised. Unfortunately that was the case with Jenny. Confusingly for Jenny was the fact that otherwise, her needs were met. She was well fed and taken care of. She had birthday parties and friends. But nevertheless, at the heart of her experience was a void because of her mother’s inability to recognize her basic need to feel seen. And father, as I said, was away most of the time working.

One result of this experience for Jenny was the nagging, if unconscious, feeling and belief that no one really cared about her. You can have all the trappings of what looks like a happy childhood but if there is no one really present with you in a vital way then these trappings become just that: trappings―they trap you into the double bind of feeling like you should feel okay about things but that deep down you don’t.

So Jenny grows up, has lots of other experiences―but never analyzes or works on the long lasting effects of this early experience, this pronounced wound to her primal nature of not having anyone in her world with her to make her experience feel real and palpable and three-dimensional. As a result, alongside her many other thoughts, feelings and beliefs, this persistent injury remained at the heart of her experience, and dictated the aperture of her emotional availability to life itself.

The central way that this showed up was as an attitude or orientation, largely unconscious, based on the feeling that nobody really cares about you, and that consequently real connections with others are not possible in any deep, life altering way. This became Jenny’s basic imprint, or thoughtform; and it showed up in her life in a number of ways: Jenny was prone to depression, she was unable to establish intimate relationships that lasted and deepened over time, and while she functioned at an above average level she deep down believed that not much else besides this rather routine experience of life was possible for her.

As a result of all this, Jenny’s underlying thoughtform about life was that it is mainly an exercise in despair, that others don’t really care about you, and not much is really possible beyond the quotidian affairs of keeping up with the pace of what life in society demands.

Below is a graphic that displays the steps I have been describing that go into making up a thoughtform:

4. What Goes into Changing or Displacing a Thoughtform?

As I have been stressing, and as the above graphic illustrates, all four components of the thoughtform must be taken into account. This flies in the face, to some extent, of the most dominant psychologies of our day, which are Positive Psychology ( Seligman, 2002 ) and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy ( Beck, Shaw, & Emery, 1980 ; Beck, 1988 ; Ellis, 1971, 1988, 1992 ). What these approaches tend to suggest is that what is needed is a change in the way Jenny thinks. Her irrational (primal, pre-rational) beliefs about life and her experience must be replaced by more rational ones. The premise for this approach is rooted in the belief that thinking creates feeling. Therefore, by changing the thinking we can change the feeling or the emotional consequence caused by the negative or irrational thinking.

Now while I do not deny that there is a strong and important reciprocity between thinking and feeling and the way they mutually influence each other, I do take issue with the notion that thinking creates emotional experience. Rather, initially at least, it is feeling that generates thinking and beliefs. Accordingly, in order to change or truly transform or displace a thoughtform we have to go to the seedbed of that thoughtform and work our way up what I have called the ladder of feeling. So let’s refer back to the graphic that illustrates the four basic components I have asserted compose a thoughtform.

Applied to Jenny, then, rather than identifying her automatic thoughts and challenging them in order to alter the emotional consequence of her experience, if we are really out to transform/displace the thoughtform we need to start with sensation and move up the ladder.

Starting with sensation, then, I would be curious to know what it is like for Jenny―in her body―when she is in that place where she is dominated by the negative thoughtform we identified early on. So I ask her, and she tells me that the sensation is closed and tight. “It’s as though I have no real access to my body at this level― there is a total lack of fluidity,” she says.

Next I would be interested in what the affect is like here. And right away Jenny tells me that the affect―the emotional energy charge―is one of constriction and even oppression. Consequently, at a feeling level this leads to the experience of despair and hopelessness. The thoughts generated by this amalgam are the ones she is most familiar with: no one really cares about you, life is void of the possibility of real deep, lasting connections to others, and not much beyond the daily task of keeping up with life’s demands is really possible.

So this is the thoughtform from the ground up, so to speak; and if we are going to seek a transformation with Jenny, we need to start from that ground in an effort to build an alternate channel for her perception and experience.

I have outlined the steps we took to begin to accomplish this task:

· First we got into the body experience at a sensation level. We worked there to allow things to become more fluid so that there was greater access to her vitality in her body.

· This lead to affects that were more expansive in nature, which in turn lead to a feeling of hope.

· This hope then lead to the thought that maybe there is more possible than she had previously assumed, and that maybe deep, lasting connections are attainable after all.

· So this became the very beginning of a new thoughtform for Jenny, still young in its inception, but strong enough to compete with or displace the old thoughtform.

· From there, with this kind of leverage in place, it became possible to entertain a new thoughtform, from the ground up so to speak.

Naturally there is a great deal more to the process than I have described here, namely the often grueling work of dealing with the origins of the dominant thoughtform from an emotional as well as a cognitive perspective. It is slow work, but gradually, as was the case with Jenny, the old thoughtform loses its pervasive grip as new sensuous, affective, emotional and cognitive material comes into view. The point here is that the old thoughtform does not transform or heal so much as it recedes or gets displaced in the face of a new relationship (with the analyst) through which new material becomes present. Slowly, then, the patient’s experience begins to change so as to admit new information at all four levels. This allows the patient to begin to construct a new worldview or thoughtform based on real experience, as the older thoughtform is seen for what it is: a relic of past trauma that can be displaced by new experience.

On the basis of this I would argue again that any real lasting change in our thoughtforms involves a displacement and construction of this kind: one that starts by recognizing the thoughform as a thoughtform (i.e. it is based not so much the way things are as the way things were) from a perspective that involves sensation, affect, feeling and thinking. Over time, and with practice, the patient can begin to displace the dominance of the old thoughtform despite its persistence.

Let’s look at another clinical example and apply the same method.

Case Study #2

Erika came to treatment with the following complaint: “I feel guilty all the time. It inhibits my freedom, and I don’t know how to get over it.” She gave as an example being out with one of her friends socially for dinner and drinks, time got away from her and when she looked up at the clock it was much later than she thought it was. Immediately she was stricken with guilt at the thought of her partner, waiting at home impatiently, when suddenly she remembered he was away that night on a business trip. She immediately relaxed, “As if I had been given permission to be out late. But I’m an adult, I’m forty-five years old, there’s no reason why I should need this kind of external permission.” Of course I agreed with her and over the course of treatment one of the things we discovered was how severely restrictive her parents were when she was a girl. There was harsh punishment for missing time deadlines and curfews along with many other rigid ways in which she was trained to behave according to their rules with absolutely no room for her own desires (she was never allowed to have friends overnight, boys were out of the picture and so on). So what she did was she would sneak these things, in terror that she might get caught, which she sometimes did and others did not. She lived in fear of being found out for living out her own desires (fear of some kind is invariably at the root of most guilt). What this produced over time was a sensation of instability, an affect of constriction, a feeling of fear, the thought that she was doing something wrong and eventually the thoughtform that she could not freely pursue her own needs and wants. This thoughtform dominated into adulthood and was present as we spoke that day in session. “Even coming here is a risk for me,” she told me.

Erika’s first thoughtform was characterized by the notion that she needed permission to pursue her needs, wants and desires, that in fact she really couldn’t pursue her needs, wants and desires freely. So given the model I am using what does the old thoughtform look like relative to the new one:

Over the course of two years, Erika was able to identify the older, dominant thoughtform, and displace it with one that served her better. Briefly, Erika was able to identify the experience of the old thoughtform at all four levels and displace it with one that served her better. The process was thick with many twists and turns, but basically Erika was able to move from the presenting thoughtform, which looked like this:

Sensation: Alarm;

Affect: Contraction;

Feeling: Fear, I’m bad;

Thought: Be careful―do as they say.

Thoughtform: It is not safe to pursue your needs, wants and desires!

And displace it with a thoughtform that started to look like this:

Sensation: Relaxed, open;

Affect: Expansivene;

Feeling: Hope;

Thought: Things are possible.

Thoughtform: I can pursue my needs, wants and desires with vitality and inner permission!

Again, as with Jenny, this process did not merely involve a change in cognition, but a relational configuration that addressed her experience at all four levels, or components of the thoughtform.

5. Conclusion

In closing I would like to raise a question that I believe helping to clarify the process of moving from the dominance of an old thoughtform to the freedom and expansiveness of a new one.

The questions I want to ask are: “What would it be like to have no thoughtform whatsoever?” and, “Is this even possible?” Certainly there is a long tradition stemming from the East that would answer this latter question in the affirmative and that would also affirm that having no thoughtform―that is, being able to transcend thoughtforms altogether―is the goal of their system or practice. A good, experientially based representative of this tradition is the marvelous teacher Adyashanti, whose most recent book, Falling into Grace ( Adyashanti, 2011 ) takes as its premise the notion that once we start believing what we think, that in fact once we start believing anything at all, we move away from the direct experience of reality and into some form of illusion (and therefore suffering). Now, intellectually it would be fairly easy to argue against the possibility of this position, for example by saying that even though the “I” that is perceiving is one with that which is perceived, the very activity of perception itself implies some kind of thoughtform process. In other words even the notion of perceiving reality without thoughtforms is itself a thoughtform of sorts; and further, as Donna Orange has pointed out ( Orange, 1992, 1995 ) the very act of perception itself implies a perspective and therefore, in the language I have been using, a thoughtform. But Adyashanti is, I believe, asking us to go deeper than this and to transcend even the need to conceptualize anything at all―and just be with what is.

The result of these two positions, I think, points to a dialectic that is ever-present in the lives of growing beings. Namely, on one side there is the need to individuate, as Jung ( Jung, 1958, 1965 ) so often emphasized―that is to become more and more of that unique expression of life that is us. On the other hand there is an equally powerful need (less emphasized in western culture) to find the way(s) in which we are always and already one with the universe since we are not merely additions to Life, but expressions of it. Taken together, this dialectic— in which the thesis is, say, individuation, and the anti-thesis is unity―is constantly working to take us into higher realms of synthesis between the two. So again, it is one of those either/or propositions that is false on its face, since obviously both working with (and sometimes suffering through) thoughforms, as well as working to transcend our identifications with them, need to be taken into account if what we want is a truly balanced, living and growing form of life that is evolving with the universe, as the universe and in the universe.

In any case, my final point is that as we work to change and displace our thoughtforms, we also change our capacity to perceive what is with less interference. That there may be some absolute that we can arrive at is less interesting to me than is the fact that we can indeed change and displace our thoughtforms, and in the process become more open, vital and relational beings.

References

- Adyashanti (2011). Falling into Grace. Boulder, Colorado: Sounds True.

- Beck, A. (1988). Love Is Never Enough. New York: Harper & Row.

- Beck, A., Shaw, B., & Emery, G. (1980). Cognitive Therapy of Depression. New York: Guilford.

- Beebe, B., & McCrorie, E. (1996). A Model of Love for the 21st Century: Infant Research Literature, Romatnic Attachment, and Psychoanalysis. Paper Presented at the 19th Annual Conference for the Psychology of the Self, Washington, DC.

- Beebe, B., Jaffe, J., & Lachman, F. (1992). A Dyadic Systems View of Communication. In N. Skolnick, & S. Warshaw (Eds.), Relational Perspectives in Psychoanalysis (pp. 53-76). Hillsdale, NJ: Analytic Press.

- Darwin, C. (1965). The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals (Original Work Published in 1872 ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Ellis, A. (1971). Growth through Reason: Verbatim Cases in Rational-Emotive Therapy. Palo Alto: Science and Behavior Books.

- Ellis, A. (1988). Rational Emotive Therapy with Alcoholics and Substance Abusers. Elmsford, NY: Pergamon Press.

- Ellis, A. (1992). The Revised ABCs of Rational-Emotive Therapy (RET). In J. Zeig (Ed.), The Evolution of Psychotherapy, The Second Conference (pp. 79-92). New York: Brunner/Maazel.

- Jung, C. (1958). Psyche and Symbol. New York: Anchore Books.

- Jung, C. (1965). Memories, Dreams, Reflections. New York: Vintage Books.

- Kohut, H. (1971). The Analysis of the Self. Madison, CT: International Universities Press, Inc.

- Kohut, H. (1977). The Restoration of the Self. Madison, CT: International Universities Press.

- Meltzoff, A., & Gopnik, A. (1993). The Role of Imitation in Understanding Persons and Developoing a Theory of Mind. In H. Tager-Flusberg, S. Baron-Cohen, & D. Cohen (Eds.), Understanding Other Minds (pp. 93-115). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Orange, D. (1992). Subjectivism, Relativism and Realism in Psychoanalysis. In A. Goldberg (Ed.), Progress in Self Psycho- logy: New Therapeutic Visions (Vol. 8, pp. 189-197). Hillsdale, NJ: The Analytic Press.

- Orange, D. (1995). Emotional Understanding. New York: The Guilford Press.

- Schore, A. (1994). Affect Regulation and the Origin of the Self. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum Associates.

- Schore, A. (1996). Interdisciplinary Developmental Research as a Source of Clinical Models. Divergent Perspectives on Early Development: Implications for Psychoanalytic Theory and Practice, New York.

- Seligman, M. (2002). Authentic Happiness: Using the New Positive Psychology to Realize Your Potential for Lasting Fulfill- ment. New York: The Free Press.

- Stern, D. (1985a). Affect Attunement. In E. Galenson, J. D. Call, & R. L. Tyson (Eds.), Frontiers in Infant Psychiatry (pp. 33-44). New York: Basic Books.

- Stern, D. (1985b). The Interpersonal World of the Infant. New York: Basic Books.

- Stettbacher, K. (1991). Making Sense of Suffering. New York: Dutton.

- Tomkins, S. (1970). Affects as the Primary Motivational System. In M. B. Arnold (Ed.), Feelings and Emotions (pp. 101- 110). New York: Academic Press.

- Tronick, E., & Adamson, L. (1980). People as Babies: New Findings on Our Social Beginnings. New York: Collier Books.

- Tronick, E., & Cohn, J. (1989). Infant-Mother Face-to-Face Interaction: Age and Gender Differences in Coordination and the Occurrence of Miscoordination. Child Development, 60, 85-92. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1131074

- Tronick, E., Als, H., & Adamson, L. (1978). Structure of Early Face-to-Face Communicative Interactions. In M. Bullowa (Ed.), Before Speech: The Beginning of Interpersonal Communication (pp. 44-69). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Zeanah, C., Anders, T., Seifer, R., & Stern, D. (1989). Implications of Research on Infant Development for Psychodynamci Theory and Practice. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 28, 657-668. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00004583-198909000-00004